Abstract

Cochlear implants stimulate the auditory nerve with amplitude-modulated (AM) electric pulse trains. Pulse rates >2,000 pulses per second (pps) have been hypothesized to enhance transmission of temporal information. Recent studies, however, have shown that higher pulse rates impair phase locking to sinusoidal AM in the auditory cortex and impair perceptual modulation detection. Here, we investigated the effects of high pulse rates on the temporal acuity of transmission of pulse trains to the auditory cortex. In anesthetized guinea pigs, signal-detection analysis was used to measure the thresholds for detection of gaps in pulse trains at rates of 254, 1,017, and 4,069 pps and in acoustic noise. Gap-detection thresholds decreased by an order of magnitude with increases in pulse rate from 254 to 4,069 pps. Such a pulse-rate dependence would likely influence speech reception through clinical speech processors. To elucidate the neural mechanisms of gap detection, we measured recovery from forward masking after a 196.6-ms pulse train. Recovery from masking was faster at higher carrier pulse rates and masking increased linearly with current level. We fit the data with a dual-exponential recovery function, consistent with a peripheral and a more central process. High-rate pulse trains evoked less central masking, possibly due to adaptation of the response in the auditory nerve. Neither gap detection nor forward masking varied with cortical depth, indicating that these processes are likely subcortical. These results indicate that gap detection and modulation detection are mediated by two separate neural mechanisms.

INTRODUCTION

Cochlear implant processors represent sound in the form of electric pulse trains to be presented to the cochlear nerve. All present-day implant processors initially analyze sound according to its frequency components using a bank of band-pass filters. The majority of processors then use the envelope of the output of each filter to modulate a constant-rate carrier pulse train, which is delivered to a cochlear electrode at the appropriate place in the cochlear frequency map. In normal-hearing listeners, cues embedded in the temporal structure of the stimulus envelope contribute to speech recognition (van Tasell et al. 1987). For cochlear implant listeners who have only limited spectral discrimination, such temporal cues are especially important. For this reason, efforts to optimize the accurate transmission of the temporal features of the acoustic envelope have the potential to improve speech reception.

The carrier pulse rate influences the temporal resolution of the electrical signal presented to the auditory nerve. Higher carrier rates allow for more detailed sampling of the stimulus envelope and transmission of envelope information at higher frequencies. Pulse rates also influence the basic firing characteristics of the auditory nerve. At low pulse rates, at which interpulse times exceed neural refractory periods, auditory nerve fibers can follow pulsatile stimulation pulse by pulse with high levels of between-fiber synchrony. As electric pulse rates increase, interpulse intervals shorten to less than the refractory periods of auditory fibers. In that condition, auditory-nerve responses become stochastic, exhibiting firing patterns more similar to those evoked by acoustic stimulation and, in particular, showing broadened dynamic ranges. These more physiological, neural response patterns have been hypothesized to enhance transmission of temporal details (Rubinstein et al. 1999). Thus any effect of increased electric pulse rate should be particularly evident in sensitivity to the stimulus envelope.

The ability of a listener to detect a gap in an ongoing sound or in an electrical pulse train is a useful measure of temporal acuity. Gap-detection thresholds in cochlear implant users have been shown to be similar to those in normal-hearing listeners (Shannon 1989), suggesting that temporal acuity is limited by processing within the central auditory pathway. The effect of pulse rate on gap sensitivity in human cochlear implant listeners has been studied with mixed results (Busby and Clark 1999; Preece and Tyler 1989; van Wieringen and Wouters 1999). These previous psychophysical studies of gap detection, however, tested pulse trains no higher than 1,250 pulses per second (pps), which are lower than the rates hypothesized to foster stochastic firing of the auditory nerve.

Modulation detection is another important measure of sensitivity to the envelope-frequency content of ongoing stimuli. Sensitivity to modulation correlates with speech recognition scores in cochlear-implant users (Fu 2002). Somewhat surprisingly, it has been shown recently that higher pulse rates result in decreased modulation sensitivity in cochlear implant listeners (Galvin 3rd and Fu 2005; Pfingst et al. 2007). This impaired transmission of modulation information has also been observed in the physiology of the auditory cortex (Middlebrooks 2008b). In that study, carrier pulse rates >500 pps resulted in increases in the stimulus modulation depths needed to produce cortical phase locking and in reductions in the maximum modulation frequencies at which cortical phase locking was observed. These results are opposite to those predicted by the theoretical advantages of increased pulse rates.

Recordings from primary auditory cortex (A1) provide a measure of the results of brain stem processing of temporal information. We used recordings from A1 of the anesthetized guinea pig to test the hypothesis that increased carrier pulse rates would result in enhanced temporal acuity for gaps in cochlear-implant pulse trains. Support for that hypothesis by early results prompted us to study the time course of recovery from forward masking as a means of exploring the mechanisms underlying the pulse-rate dependence of gap detection. The results of those studies are consistent with distinct peripheral and central mechanisms.

The present results yield new understanding of central processing of temporal information and have implications for processing strategies for auditory prosthesis.

METHODS

Overview

Experiments were conducted at the University of Michigan with the approval of the Committee on the Use and Care of Animals. Both single-unit and multiunit activities were recorded from the A1 of anesthetized guinea pigs using multisite recording probes. Data were collected and stimuli were generated with TDT System III hardware (Tucker-Davis Technologies, Alachua, FL) connected to a personal computer running MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) and using software developed in this laboratory. Each animal was studied initially with acoustic tone stimulation, which served to guide placement of the recording probe relative to the cortical frequency representation. After suitable placement, the probe was fixed in place. In the majority of animals, cortical responses to additional acoustic stimulation were recorded. The animal was then deafened in both ears and a cochlear implant was inserted into the cochlea contralateral to the cortical recording sites. Responses to electrical cochlear stimulation were recorded for the purposes of this study. Recording sessions lasted 8–20 h.

Animal preparation and data acquisition

Recordings were made in the A1 in the right hemispheres of 22 adult pigmented guinea pigs. Animals were of either sex and weighed 400–1,000 g. Anesthesia was induced with an intramuscular injection containing 40 mg/kg ketamine hydrochloride and 10 mg/kg xylazine hydrochloride and maintained with intramuscular ketamine hydrochloride. Body temperature was monitored with a rectal probe and maintained at or above 37°C with a heating pad.

To eliminate the possibility of unintended acoustic stimulation, the right ear was deafened by opening the bulla and ablating the cochlea. The auditory cortex was exposed on the right side. Primary auditory cortex was identified by its proximity to the pseudosylvian sulcus and by the characteristic rostrolateral to dorsomedial increase in characteristic frequencies, verified by recordings at three or more probe positions. When a cortical location within A1 with a characteristic frequency between 8 and 32 kHz had been identified, the recording probe was inserted perpendicular to the surface of the cortex. This frequency range corresponded to the tonotopic location of the cochlear implant to be placed in the basal turn of the cochlea. The exposed dural surface and silicon shank of the recording probe were covered with warmed 10% agarose. The probe was fixed in place with methacrylate cement and dental sticky wax.

The cortical recording probe (NeuroNexus, Ann Arbor, MI) was a single thin-film silicon shank with 16 iridium-plated recording sites at 100-μm intervals. The probe was 15 μm thick and 100 μm wide, tapering to the tip. Signals from all 16 recording sites were recorded simultaneously, digitized at 24.4 kHz, low-pass filtered, resampled at 12.2 kHz, and stored for off-line analysis. An artifact-rejection procedure was used to eliminate electrical artifact resulting from the electrical cochlear stimulus (Middlebrooks 2008a,b). On-line, a simple peak-picker was used to detect unit activity for experimental control. Off-line, spikes were identified using custom software that classified waveforms on the basis of the time and amplitude differences between spike peaks and troughs (Middlebrooks 2008a). Only the off-line–sorted spikes were used for quantitative analysis. We identified some well-isolated single units, but most channels provided unresolved spikes from two or more neurons. Herein, a “unit” will refer to the spikes identified on a single recording channel and will include both multiunit clusters and single units; well-isolated “single units” will be specifically described as such.

After acoustic stimulation, the left bulla was opened to expose the cochlea and a small cochleostomy was drilled in the basal turn. Perilymph was wicked out and replaced with a 10% neomycin sulfate solution, which is toxic to hair cells. After 2 min, fluid in the basal turn of the cochlea was again replaced with 10% neomycin. A cochlear implant was inserted into the scala tympani through the cochleostomy. The cochlear implant was a six- or eight-channel banded scala tympani electrode (Cochlear, Centennial, CO), similar in design to the Nucleus 22 model designed for human use. Four to six bands could be placed within the scala tympani in our guinea pig preparation.

Current source density analysis (Müller-Preuss and Mitzdorf 1984) was used to estimate the locations of recording sites relative to cortical layers. The most consistent feature was a short-latency sink that we have found previously in histological reconstructions to correspond to the transition from layer III to layer IV (Middlebrooks 2008a). That landmark provided a depth reference that could be compared across animals (as in Figs. 4 and 8).

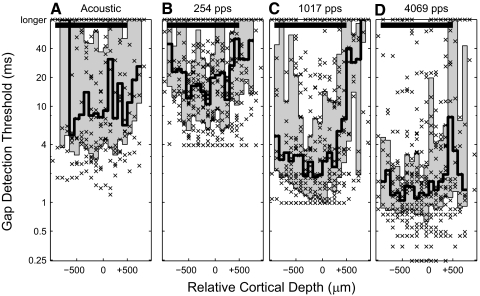

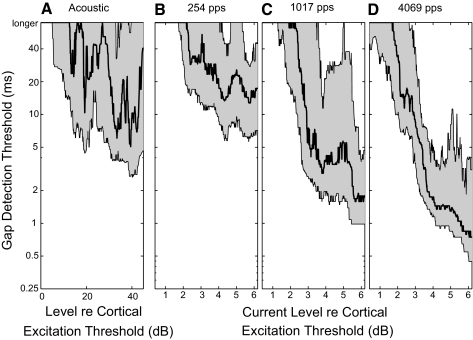

FIG. 4.

Gap-detection thresholds across cortical depth. Cortical depth is measured relative to the layer III/IV boundary, identified by the cortical depth exhibiting the earliest current sink. Symbols depict the individual gap-detection thresholds. The shaded area represents the intraquartile range, computed in 100-μm increments of depth. The shallowest and deepest locations were merged so that distributions contained ≥10 gap-detection thresholds. The solid black bar at the top of the graph represents the cortical depths over which there was no significant difference between gap-detection thresholds with cortical depth for any pulse rate (P ≤ 0.12, Kruskal–Wallis, data grouped in 300-μm increments of cortical depth). The gap-detection thresholds were obtained at 4–6 dB above detection threshold for electric stimulation and 30–45 dB above detection threshold for acoustic stimulation.

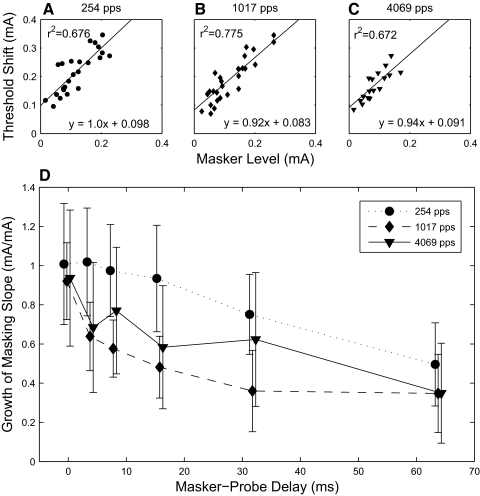

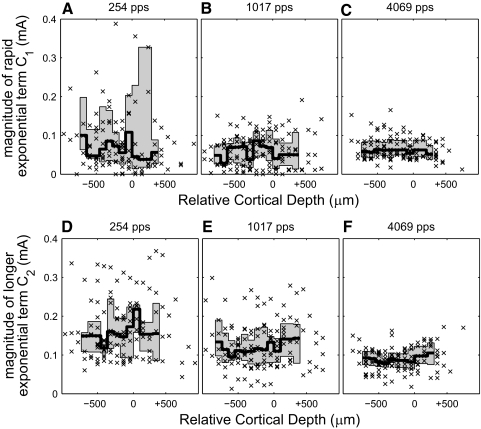

FIG. 8.

Growth of masking. The increase in forward masking with masker level is linear at all time points after masker offset and the slope decreases over time. A–C: growth of masking at 0 ms after masker offset. Each data point represents the median values of masker level and probe threshold shift across all units recorded in one animal. Each animal contributed at least two data points. D: growth of masking slopes at various masker-probe delays. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals of the least-squares linear regression.

Stimuli

Acoustic and electric stimuli were created by TDT System III hardware controlled by a personal computer with custom software written in MATLAB. The data required to compute an individual measurement, such as a detection threshold, gap-detection threshold, or forward-masking recovery function, were collected in a single block of trials and several measurements were obtained from each block. For example, gap-detection stimuli were varied over presentation level and gap duration to obtain gap-detection thresholds for each of the presentation levels. Each configuration of stimulus parameters was presented 20 times and, within each iteration, the stimuli were interleaved randomly. To avoid systematic effects of the duration of anesthesia, the order of testing of various parameters was varied among experiments.

Acoustic stimuli consisted of tones and broadband-noise bursts presented from a loudspeaker located about 15 cm from the left ear; tone and noise levels were calibrated and noise spectra were flattened, using a precision microphone positioned at the approximate position of the ear in the absence of the animal. Tonal stimuli were used to characterize the location of the recording probe in the cortex on the basis of characteristic frequencies of neurons. The depth of the probe relative to cortical lamina was estimated from current source density analysis of 200–300 presentations of 4-ms broadband-noise bursts. Gap-detection thresholds for broadband noise were obtained in normal-hearing conditions in 15 of the 22 animals. Pregap markers lasted 200 ms, postgap markers lasted 120 ms, and both were presented at the same sound level. Gap duration and stimulus intensity were varied parametrically. Intensity levels were set to 20 and 40 dB above the detection threshold of the pregap marker.

Cochlear-implant stimulation was presented to all animals in this study. Electrical stimuli were generated by a custom eight-channel optically isolated current source, controlled by a TDT RX8 D/A converter. A monopolar electrode configuration was used in which a single intracochlear electrode was active and a wire in a neck muscle was the return. Thresholds were estimated for each cochlear-implant electrode and the electrode with the lowest threshold (always one of the three most apical electrodes) was selected for subsequent stimulation. Figure 1A depicts the pulse shape. The phase duration was 41 μs, the interphase interval was 0 ms, and the leading phase was cathodic. The pulse rates tested were 254, 1,017, and 4,069 pps.

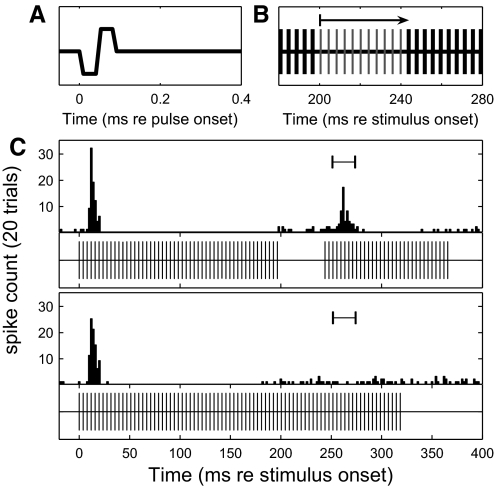

FIG. 1.

Gap-detection stimuli and cortical responses. A: electric pulse shape. B: gaps presented in electric pulse trains in this study were integer multiples of the carrier period—in this case, about 4 ms for 254 pulses per second (pps). C: peristimulus time histogram (PSTH) of responses of a well-isolated single unit to a gap-detection stimulus with a 43-ms gap (top) and with no gap (bottom). Underneath each PSTH is a diagram of the eliciting stimulus. The interval for comparison of spike count between gap and no-gap conditions is indicated on both histograms.

Electric gap-detection stimuli consisted of pulse trains in which gaps were formed by deleting one or more pulses. Durations of pre- and postgap markers were 196.6 and 121.9 ms, respectively, which corresponded to integer multiples of the pulse period. As shown in Fig. 1B, gap duration was defined relative to the first missed pulse, meaning that a gap of 0 ms was an uninterrupted pulse train. The minimum possible nonzero gap (corresponding to one missed pulse) was 3.93, 0.983, or 0.246 ms for pulse rates of 254, 1,017, and 4,069 pps, respectively. Uninterrupted pulse trains were also tested as the “0-ms” control stimuli. The longest gap routinely tested was 64 ms. Gap-detection stimuli were presented at several current levels, most often 2, 4, and 6 dB above detection threshold. During gap-detection trials, pulse rates and pre- and postgap marker durations were fixed, although stimulus intensity and gap duration varied. Each block of trials yielded one gap-detection threshold per stimulus intensity.

Forward masking was measured in 10 animals to shed light on mechanisms contributing to the pulse-rate dependence of gap thresholds that was observed. Forward-masking stimuli were similar in form to gap-detection stimuli in that they also consisted of a pregap stimulus (masker), a silent gap (delay), and a postgap stimulus (probe), but differed in two important ways. First, the probe stimulus was varied in intensity independent of the level of the masker to determine the probe threshold at each time delay. Second, the probe stimulus was shortened to measure the recovery from masking more precisely at one point in time. Masker duration was 196.6 ms and probe duration was 3.9 ms; that probe duration corresponded to two pulses at the 254-pps rate and 17 pulses at the 4,069-pps rate; our previous work in this animal model has shown that cortical thresholds are dominated by the first approximately 1 ms of electrical pulse trains (Middlebrooks 2004). Eight to 18 delays were presented, extending from 0 to 64 ms from masker offset. Masker levels were 0–6 dB above unmasked detection threshold. Masker and probe durations were fixed in each block of trials, but masker intensity, probe intensity, and delay varied parametrically. A recovery-from-masking curve was generated for each masker intensity presented in the stimulus block. In addition, a threshold was measured for the 3.9-ms unmasked probe stimulus.

Data analysis

Detection thresholds based on neural spike counts were measured using signal-detection procedures (Green and Swets 1966; Macmillan and Creelman 2005); the specific procedures are described in Middlebrooks and Snyder (2007). Briefly, receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were formed from the trial-by-trial distributions of spike counts in probe trials and background trials; the characteristics of the probe and background trials in various conditions are defined in the following text. The area under the ROC curve gave the percentage correct detection, which was expressed as a detection index (d′).

In unmasked detection trials, the probe was the pulse train to be detected and the background was no stimulus. Spikes were counted in the 7- to 30-ms interval after probe onset or in an equivalent interval during the background. In gap-detection trials, probe trials contained a gap in the pulse train and background trials had an uninterrupted pulse train (Fig. 1C). Spikes were counted in the 7- to 30-ms interval after the onset of the postgap pulse train or in an equal interval in the background. In forward-masking trials, the probe was a pulse train of varying level presented at a particular time after masker offset and the background was the masker with no probe. Spikes were counted in the 7- to 20-ms interval after probe onset or in an equivalent postmasker interval in the absence of the probe. In all conditions, plots of d′ versus probe level or versus gap duration were interpolated to find thresholds at d′ = 1. In the case of gap detection, whereas all gaps presented were integer multiples of the carrier pulse period, interpolated gap-detection thresholds could fall anywhere between the minimum and maximum gaps tested.

Recovery from masking was tracked by measurement of probe-detection thresholds at successive delays after masker offset. At a delay of 0 ms, the probe stimulus had to be elevated above the level of the masker to elicit a significant response. Probe thresholds were expressed in units of current in microamperes (μA). A single-exponential function was fit to current shifts relative to the unmasked threshold. The function had the form

| (1) |

where Θm is the masked threshold of the probe stimulus, Θ0 is the unmasked threshold, τ is the time constant of recovery from forward masking, and C and C0 are constants. Next, a dual-exponential function was fit to the same data

| (2) |

where Θm is the masked threshold of the probe stimulus, Θ0 is the unmasked threshold, τ1 and τ2 are the time constants of recovery from forward masking, and C1 and C2 are constants, referred to as the magnitudes of the exponential recovery processes. All fitted parameters were constrained to be positive. The fitting algorithm was a separable nonlinear least-squares curve fit using the Levenberg–Marquardt process (Nielsen 2000).

The data were fit in several ways. Originally, each forward-masking condition for each unit was fit with the single-exponential function. Afterward, the dual-exponential function was applied to the data with different constraints. First, each forward-masking condition for each unit was fit with the dual-exponential function. Then, the fitting functions for each unit were constrained across stimulus pulse rate so that the time constants τ1 and τ2 were obtained for each animal, whereas C1 and C2 varied freely. In this procedure, the parameter that was minimized was the combined sum of squared errors (CSSE), defined as

| (3) |

where SSEp,ln is the sum of squared errors between the data and the fitted curve for the unit n, at the pulse rate p, and current level l, for all pulse rates and current levels presented. With each iteration of the curve-fitting algorithm, the C1 and C2 parameters for each curve fit shifted independently of one another to minimize the CSSE, whereas the τ1 and τ2 parameters shifted together so that they were always common to all fitted curves. The curve fit for an individual recovery function was selected for further analysis if it met the criteria R2 >0.7 and long time constant τ1 <1,000 ms. The latter criterion excluded one animal from the analysis.

To measure growth of masking, we calculated median probe-threshold shifts elicited by varying masker levels presented to each animal. Median values were calculated across all units for which a detection threshold was obtained. Linear regressions were then computed for each growth-of-masking function. All linear regressions were significantly different from a horizontal line through the mean and 95% confidence intervals for each linear fit were computed.

Levels of gap-detection stimuli and forward maskers were set relative to thresholds for detection of unmasked stimuli. Such detection thresholds varied across cortical depth. Thus the intensity of a given stimulus could be computed either by comparison with the threshold of each individual channel, resulting in 16 individual levels, or by comparison with one detection threshold chosen to represent the probe penetration, such as the mean or the minimum detection threshold. We performed all analyses with both methods, which yielded similar results. The results presented herein were all plotted using the first method, with each unit assigned its own detection threshold. Units for which the detection threshold was above the maximum level presented were not considered in the analysis.

RESULTS

Neural responses to gap-detection stimuli

Qualitatively similar response patterns were recorded in response to noise bursts and to electrical pulse trains at various pulse rates. We presented long, uninterrupted pulse trains for the 0-ms gap condition, shown in Fig. 1C and in the bottom row of Fig. 2. These control responses were typical in that there was a robust response to the stimulus onset, a period of suppression typically lasting 50 to 200 ms, and often a weak, temporally irregular tonic response beginning after the period of suppression. These response characteristics were similar across all electric pulse rates. The period of suppression and the tonic response typically were more temporally diffuse in acoustic-stimulation conditions than in electric-stimulation conditions, possibly because the broadband acoustic noise contained greater envelope structure than that present in the unmodulated electrical pulse trains.

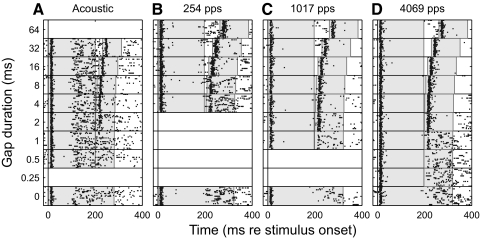

FIG. 2.

Raster plot of multiunit ensemble response to gap-detection stimuli. Each row corresponds to one trial and each dot is one spike. Trials are ordered by gap duration. Twenty trials were presented for each gap condition. Blank areas are placeholders for gap durations that were not presented for a given stimulus condition. The shaded gray areas represent the durations of pre- and postgap markers. Gap thresholds in this example were 3.50 ms for acoustic and 3.93, 1.08, and 0.75 ms for 254, 1,017, and 4,069 pps, respectively.

Introduction of a gap of sufficient duration resulted in an onset response to the postgap noise burst or pulse train, as seen in the top blocks of rasters in Fig. 2. In addition, these onset responses to the postgap stimulus were succeeded by a similar period of suppression and tonic response at all but the shortest detectable gaps. As described in methods, gap thresholds were computed using an ROC procedure that compared spike counts within restricted time windows in gap and no-gap conditions. In the illustrated example, gap-detection thresholds were: 3.50 ms for acoustic; 3.93 ms for 254 pps; 1.08 ms for 1,017 pps; and 0.75 ms for 4,069 pps. This unit exhibited gap thresholds among the shortest 10% among the unit sample.

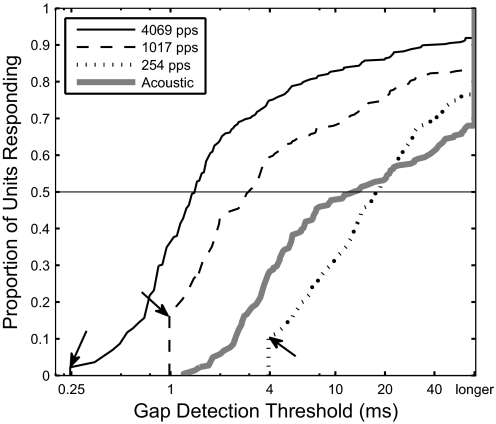

The example in Fig. 2 is typical of our data set in that gap-detection thresholds tended to be shorter for higher pulse-rate stimuli than that at lower rates. That tendency was significant across the population of 336 units (P < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test; nonparametric one-way ANOVA). We calculated the cumulative distribution function (CDF) for each pulse rate, shown in Fig. 3. The median gap-detection thresholds, equivalent to the CDF at P = 0.5, were well separated: 16.7 ms for 254 pps, 2.7 ms for 1,017 pps, and 1.3 ms for 4,069 pps.

FIG. 3.

Cumulative distribution of gap-detection thresholds. The graph represents the proportion of the population of units of each pulse rate with gap-detection thresholds shorter than the given duration. Arrows indicate the proportion of units responding to one missed pulse for each pulse rate. These distribution functions were limited to gap thresholds obtained at 4–6 dB above detection threshold and channels located in −800- to +400-μm cortical depth.

The minimum nonzero gap duration that could be tested was determined by the duration of one missed pulse, which varied among pulse rates from 3.93 ms at 254 pps to 0.248 ms at 4,069 pps. It was a concern that the gap-detection thresholds might vary by pulse rate simply due to this trend. In Fig. 3, the proportions of units responding to one missed pulse are indicated with arrows. At every pulse rate, far fewer than 50% of units responded with an onset burst following only one missed pulse. For that reason, median values of gap-detection thresholds were not influenced by minimum tested gap durations that varied among pulse rates. Nevertheless, we compared the d′ statistic for a 3.93-ms gap at each pulse rate for the data depicted in Fig. 3 and found that there was a significant difference in the median d′ across the population: 0.32 for 254 pps, 1.32 for 1 kpps, and 1.71 for 4 kpps (P < 0.0001, Kruskal–Wallis). Within individual units, the d′ measured at any particular gap duration tended to increase with increasing stimulus pulse rate. Acoustic gap-detection thresholds did not have an experimentally imposed minimum, but the minimum gap-detection threshold observed was >1 ms.

As many as roughly 20% of units failed to respond to the postgap marker after the longest gap that was tested, 64 ms. The proportion of units that failed to respond after the longest gaps increased with decreasing pulse rates (P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney rank-sum test).

Laminar dependence of gap-detection thresholds

We assessed the degree to which intracortical mechanisms contribute to gap-detection thresholds. We reasoned that systematic differences in gap thresholds among cortical laminae would be indicative of intracortical processing, whereas a lack of such differences would suggest that gap thresholds are determined primarily by subcortical processes. As described in methods, we used current source density analysis to estimate the depths of recording sites relative to the transition between layers III and IV. Median gap-detection thresholds and intraquartile ranges were calculated for each relative cortical depth (Fig. 4). Gap thresholds tended to be large at the deepest and shallowest depths. We speculate that this was due to the generally poor responses in those laminae observed in anesthetized conditions. Aside from the deepest and shallowest depths, however, there was no significant dependence of gap-detection threshold on relative cortical depth across broad ranges of cortical depth. Solid black bars in Fig. 4 represent the relative cortical depths from −800 to +700 μm, across which there was no significant dependence of gap threshold on cortical depth for any tested pulse rate (P = 0.12, Kruskal–Wallis; depths grouped with 300-μm resolution).

Gap thresholds depend on stimulus level

In human listeners, gap-detection thresholds decrease with increasing stimulus intensity in both acoustic and electric conditions. In the present physiological study, stimulus levels were fixed relative to detection levels and detection levels varied with pulse rate. For that reason, the pulse rates were presented at varying levels in the same animal. We tested whether differences in stimulus levels could have accounted for the observed dependence of gap thresholds on pulse rates. Figure 5 shows the distributions of gap thresholds as a function of stimulus level for the three tested pulse rates.

FIG. 5.

Gap-detection thresholds by level. This graph shows distributions of gap-detection thresholds for all units for which a detection threshold was obtained. Distributions were computed within a moving window that encompassed 10% of the sample. The shaded area is the intraquartile range and the black line is the median gap-detection threshold. Thresholds were limited to those obtained from −800- to +600-μm cortical depth.

Gap-detection thresholds decreased substantially with increasing stimulus level for both acoustic stimulation and electric stimulation at all pulse rates. Gap sensitivity near detection threshold was poor at all pulse rates, with many units failing to respond to the longest gap tested. Improvements in gap-detection thresholds started to level off at stimulus levels >4 dB above threshold for electric stimulation. The pulse-rate dependence of gap thresholds was most evident at these higher stimulus levels. To consider gap-detection thresholds from a near-asymptotic portion of the dynamic range, Figs. 3 and 4 plotted only thresholds obtained at 4–6 dB above detection threshold for cochlear-implant stimulation and 30–45 dB above detection threshold for acoustic stimulation. We note that the highest levels tested relative to detection threshold were higher in absolute (μA) terms for the 254-pps pulse rate than for the 4,069-pps rate because temporal integration at the highest rate resulted in lower detection thresholds. Thus gap-detection thresholds were dependent on stimulus levels relative to threshold rather than on absolute stimulus levels.

Forward-masking recovery depends on pulse rate

One possible explanation for the increased temporal acuity (i.e., decreased gap-detection thresholds) associated with higher pulse rates is that the recovery from forward masking might be faster when pulse rates are higher. We tested that hypothesis by measuring masked thresholds across a range of masker-probe delays, fitting recovery-from-masking curves, and then computing recovery functions (as described in methods). The first function fit to the data, Eq. 1, was a single-exponential curve with a constant term representing residual masking. The curve fits demonstrated a significant interaction of pulse rate and exponential time constant (P < 0.001). The median time constants (τ in Eq. 1) were: 18.9 ms at 254 pps, 10.7 ms at 1,017 pps, and 9.1 ms at 4,069 pps. These curve fits are not displayed.

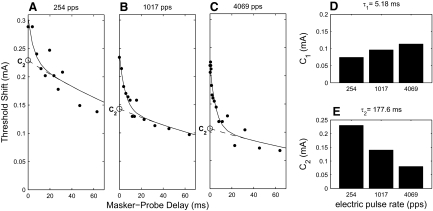

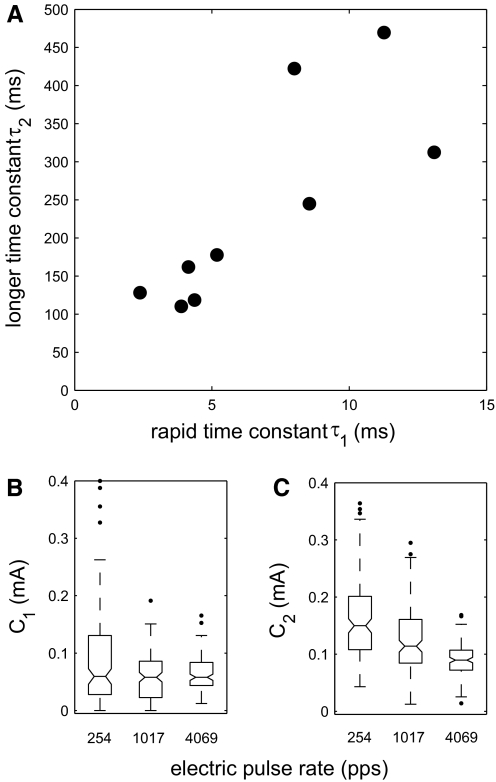

The single exponential produced a reasonable fit to the data, but it was difficult to construct a plausible physiological mechanism that would explain a dependence of τ (Eq. 1) on pulse rate. For that reason, a dual-exponential function, given by Eq. 2, was fit to the data; an example for one unit is shown in Fig. 6. These curves comprised long and short recovery functions and a pair of time constants was computed for each animal (τ1 and τ2 in Eq. 2) as described in methods. For a single pair of time constants to describe all forward-masking conditions, these time constants should be independent of stimulus level, pulse rate, and cortical depth. To verify these assumptions, we also fit a dual-exponential curve to each recovery-from-masking data set independently. When each stimulus condition was fit with a different pair of time constants (not shown), these time constants did not differ across stimulus level (P = 0.12, ANOVA), pulse rate (P = 0.08, ANOVA), or cortical depth (P = 0.5, ANOVA). The two time constants obtained for each animal are displayed in Fig. 7A. The magnitude of the contribution of the long exponential recovery process (C2 in Eq. 2) was significantly smaller at higher pulse rates (P < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis) (Fig. 7C), whereas the magnitude of the short exponential recovery (C1 in Eq. 2) was not (P = 0.083, Kruskal–Wallis) (Fig. 7B). When combined, these terms describe a more rapid recovery process at higher pulse rate conditions. Faster recovery should lead to a shorter gap-detection threshold because the lagging stimulus would elicit a response at a shorter gap.

FIG. 6.

Recovery from forward masking for one unit. A–C: threshold shifts at 11–18 time points after masker offset are plotted for each pulse rate condition, along with the constrained curve fits. The maskers were presented at 4.3, 4, and 3.8 dB above this unit's threshold for 254, 1,017, and 4,069 pps, respectively. The magnitude of the longer exponential component (C2) is indicated on the y-axis. Magnitude of the rapid (D, τ1 = 5.18 ms) and longer (E, τ2 = 177.6 ms) exponential terms for the curve fits by pulse rate.

FIG. 7.

Summary of forward-masking curve fits. A: time constants obtained for each animal that met goodness-of-fit criteria. B: magnitude of rapid time constant component (C1) at each pulse rate across all units meeting the goodness-of-fit criteria. C: magnitude of longer time constant component (C2) at each pulse rate across all units meeting the goodness-of-fit criteria.

Growth of masking is linear

The nonlinear dependence of gap-detection thresholds on stimulus level might arise solely from the exponential dependence of masking on time after stimulus offset or it might reflect an additional nonlinearity in the growth of masking. We measured the linearity and magnitude of the growth of masking for a series of time points after masker offset, summarized in Fig. 8. Within-animal growth-of-masking functions were uninformative because only two masker levels were presented to most animals. However, it is notable that growth-of-masking functions compiled across animals were linear. Growth of masking slopes were near 1 at masker offset and were significantly shallower at 64 ms after masker offset for all pulse rates. Thus the decrease in gap-detection thresholds at higher stimulus levels is consistent with the fact that the masking provided at one stimulus level is insufficient to mask a probe presented at the same stimulus level.

Laminar dependence of forward masking

Figure 9 demonstrates another important similarity to gap-detection thresholds: the magnitude and time course of forward masking did not vary significantly with cortical depth. This suggests that the forward masking and subsequent recovery processes described in our equation reflected subcortical processing.

FIG. 9.

Forward masking across cortical depth. Each symbol represents one term from a dual-exponential curve fit to ≥4 forward-masking time points. The shaded area represents the intraquartile range of the population and the black line represents the median magnitude. Cortical depth is measured relative to the layer III/IV boundary as in Fig. 4. There is no significant difference in masking over cortical laminae. Forward-masking recovery constants are based on data for all masker levels. A–C: magnitude of rapid exponential component (C1). D–F: magnitude of longer exponential component (C2).

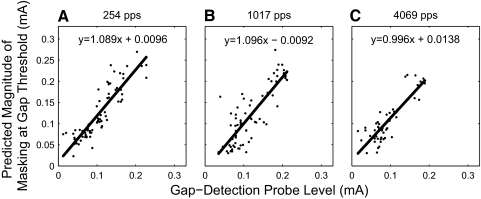

Forward-masking model predicts gap-detection thresholds

To test the hypothesis that forward masking and gap detection reflect the same underlying auditory processes, we used our forward-masking curve fits to create a model of gap detection. In a subpopulation of 76 units, both gap-detection and forward-masking data were available with identical masker levels. Of these units, 38 yielded a gap-detection threshold that exceeded 64 ms for one or two stimulus conditions, primarily at low stimulus levels and pulse rates. These conditions were excluded, since the exact durations of the gap thresholds were not measured. We then took the forward-masking curve fit and the gap-detection threshold for each of the remaining stimulus conditions for each unit and computed the expected shift in detection threshold at the duration of the first detectable gap, using the recovery-from-masking equation. In Fig. 10, we compared these computed thresholds to the actual postgap probe stimulus in the gap detection condition that evoked the minimum detectable gap and computed linear regressions. The 95% confidence intervals included a slope of 1 and intercept of 0 for every pulse rate, indicating that our gap-detection and forward-masking results are in good agreement. Note that these data points are drawn from responses to the entire range of current levels. This result supports both our model of forward masking and our hypothesis that gap detection and forward masking are supported by similar temporal processes.

FIG. 10.

Forward-masking curve-fit predictions for gap-detection results. The magnitude of the forward-masked threshold shift for one unit was calculated at the masker-probe delay corresponding to the gap-detection threshold for that unit and compared with the actual postgap marker level that elicited the detection of the gap. For all pulse rates, 95% confidence interval ranges of the linear regression included the equality equation.

DISCUSSION

The principal finding of this study is that gap-detection thresholds decrease substantially with increasing pulse rate. We begin the discussion by comparing this result with previous psychophysical and physiological studies. Second, we consider the pulse-rate dependence of gap threshold in the context of an exponential recovery model of forward masking. We then discuss the effect of stimulus level on gap-detection thresholds. Finally, we conclude with the observation that gap detection represents a temporal process distinct from modulation detection.

Comparison with human psychophysics

The present physiological results indicate that gap-detection thresholds measured in the auditory cortex are substantially shorter at higher pulse rates. A decrease in perceptual gap-detection threshold with high pulse rate has been observed in human cochlear-implant users although, as is often the case in these studies, the range of performance across subjects is broad. Preece and Tyler (1989) tested detection of gaps in 63- to 4,000-Hz electric sinusoids by cochlear-implant listeners. After matching loudness across carrier rates, they observed that gap thresholds decreased with increasing stimulus frequency at current levels near detection threshold, although there was no difference in gap-detection thresholds between carrier frequencies at higher current levels. van Wierengen and Wouters (1999) compared gap detection at 400 and 1,250 pps and found that gap-detection thresholds were shorter at the higher pulse rate for three of four subjects; the fourth subject showed no difference in gap sensitivity. Grose and Buss (2007) did not explicitly compare gap-detection thresholds across pulse rate, but obtained thresholds of ≤1 ms in several listeners at a pulse rate of 3 kpps. This accords with the current observation of gap-detection thresholds <1 ms at 4,069 pps and is shorter than the typical 2- to 5-ms psychophysical gap-detection thresholds obtained at lower pulse rates (Shannon 1989). Studies that tested stimulation rates only ≤1,000 pps have shown little or no correlation between pulse rate and gap-detection threshold. Busby and Clark (1999) found no consistent pattern of sensitivity across pulse rates in the range 200–1,000 pps. Similarly, Chatterjee et al. (1998) also observed no significant difference in two of three listeners across pulse rates from 125 to 1,000 pps.

Comparison with physiological studies of gap detection

Studies of auditory-evoked cortical potentials in human subjects demonstrate that the temporal acuity of the auditory cortex is comparable to behavioral gap-detection thresholds in normal-hearing listeners. Gaps in broadband noise elicited middle-latency responses associated with primary auditory cortex at gap durations similar to the behavioral thresholds measured in the same listeners (Lister et al. 2007). In a study of mismatch negativity (Heinrich et al. 2004) using gaps in tones, dipole source modeling suggested that the gaps were represented in or near the primary auditory cortex.

Previous electrophysiological studies focused on neural mechanisms in the auditory cortex for the detection of gaps in noise. Eggermont (2000) described the responses of cat primary auditory cortex under anesthesia to gaps with varying leading burst durations. For broadband-noise stimuli similar in temporal structure to those tested in the current study, gap-detection thresholds were 5–10 ms. Wang et al. (2006) measured local field potentials obtained in the primary auditory cortices of normal-hearing, awake guinea pigs and observed gap-detection thresholds of 4–6 ms with broadband-noise bursts. These thresholds are equal to or in some cases longer than psychophysical thresholds and are consistent with the acoustic gap-detection thresholds obtained in this study.

Neural basis of gap-detection dependence on pulse rate

Gap-detection thresholds can be elucidated by examination of the time course of cortical sensitivity after the offset of the pregap stimulus. We obtained forward-masking results that were in agreement with our gap-detection findings. Higher pulse rates evoked shorter-lasting forward masking and this difference was more pronounced at longer masker-probe delays. Forward masking and gap detection likely result from the same neural mechanisms, given that these stimuli share a common temporal structure and have been shown to give consistent results in human psychophysical studies (Plomp 1964). This hypothesis is supported by the constancy of temporal acuity across cortical laminae that we observed in both gap detection and forward masking. The forward-masking data therefore provide a framework in which to understand gap detection.

To quantify the influence of pulse rate on recovery from masking, we fit two curves to the forward-masking data obtained in this study. The first was a single exponential similar to that used in the examination by Nelson and Donaldson (2002) of electric pulse train forward masking in human listeners. Using this approach on the data in the present study, we obtained time constants of recovery that were significantly shorter at higher electric pulse rates. This result implied that the pulse rate of a forward masker influenced the speed of recovery following the cessation of the masker, which is difficult to explain with a physiologically plausible model. For that reason, we considered models incorporating more than a single component.

We hypothesized that the forward masking observed in cochlear-implant stimulation has both peripheral and central components that could be reflected in a dual-exponential model. Such a dual-exponential model was used by Chatterjee (1999) to fit psychophysical recovery-from-masking curves in human cochlear implantees: she obtained one rapid (2–5 ms) and one longer (50–200 ms) time constant. The rapid exponential component likely reflected adaptation within the auditory nerve. Zhang et al. (2007) described responses to electric pulse trains in the cochlear nerve of the cat. They measured a rapid time constant of adaptation with a median value of 8 ms, which did not differ significantly between 250-, 1,000-, and 5,000-pps pulse trains. They attributed this time constant to refractory effects in the auditory nerve, which should also contribute to forward masking. The longer time constant observed by Chatterjee (1999) is more difficult to attribute to any one physiological source. In that study, the longer time constant was quite variable between subjects. Support for a forward-masking mechanism central to the auditory nerve is provided by the observation reported by Shannon and Otto (1990) that the time course of recovery from pulse train forward masking is similar in listeners with cochlear implants and auditory brain stem implants. Nelson and colleagues (2009) measured forward masking in the inferior colliculi of awake marmosets. In a subpopulation of neurons, forward-masked thresholds were similar to those measured psychophysically in normal-hearing subjects (such as Oxenham and Plack 2000), reflecting a central contribution to forward masking that was most consistent with an adaptive or inhibitory mechanism. The 100- to 500-ms time constant in the current study also may reflect the sum of several processes central to the auditory brain stem.

Using this dual-exponential function and allowing the time constants to vary freely, we obtained results similar to those in Chatterjee's study in 9 of 10 animals. These time constants did not differ systematically with pulse rate, stimulus level, or cortical depth, supporting our hypothesis that the underlying neural mechanism remains the same at any pulse rate or stimulus level. To obtain the best measurement of each time course, we linked the curve fits together so that a single pair of time constants was obtained for each animal. The rapid time constants fell in the range of 3–13 ms, with a median of τ = 5.18 ms; the longer time constant was 100–500 ms with a median of τ = 177 ms. The results of this model were mutually consistent with our gap-detection results, in that the forward-masking results could predict the threshold shift at the gap-detection threshold in a subset of units for which both stimuli were presented at the same current levels. The predicted threshold shift correlated strongly with the level of the postgap marker above threshold.

The time course of recovery from forward masking explains the dependence of gap detection on electric pulse rate. Neither the time constant nor the magnitude of the rapid recovery-from-masking process, likely located in the periphery, differed with increasing pulse rate. In contrast, the longer recovery process, putatively reflecting more central contributions, contributed a greater magnitude of masking in response to a lower-rate pulse train. Higher pulse rates evoked less central masking, leading to significantly lower masked thresholds <10 ms after masker offset. Therefore shorter gap-detection thresholds occurred at high pulse rates because the masked detection threshold dropped below the level of the postgap marker relatively quickly after masker offset.

Results in human cochlear-implant users are consistent with the notion of distinct peripheral and central mechanisms. Brown and colleagues (1996) compared electrically evoked compound action potential (ECAP) recovery and psychophysical forward masking with the same stimuli. Whereas ECAP recovery followed a time course similar to that described by the rapid time constant in the current study, psychophysical recovery from masking frequently followed a longer time course, indicating an additional contribution to forward masking central to the auditory nerve. This study also demonstrated selective activation of this central component. Within each individual listener, stimulating one cochlear-implant channel might yield a rapid recovery similar to that measured with ECAP, whereas other channels elicited a longer time course of recovery.

In the auditory nerve, the amount of adaptation to a stimulus several hundred milliseconds in duration increases with increasing pulse rate (Zhang et al. 2007). A low-rate pulse train evokes an auditory nerve response that maintains its spike rate throughout the duration of a long pulse train, providing constant input to central processing centers for hundreds of milliseconds. A high-rate pulse train, on the other hand, elicits more spikes at the onset of the stimulus, but produces a less sustained response. During a masker stimulus of sufficient length, ascending input to higher processing centers decreases at higher pulse rates, leading to a more rapid time course of recovery. This leads in turn to shorter gap-detection thresholds.

Our previous work in this animal model has demonstrated decreases in thresholds for activation of the auditory cortex as carrier pulse rates are increased beyond about 1 kpps (Middlebrooks 2004). That effect was interpreted to reflect temporal integration of electrical pulses at the level of the auditory nerve. Although that form of temporal integration resulted in an overall increase in sensitivity to the onsets of masker pulse trains and probe stimuli, there was no indication that temporal integration produced any net increase in the sustained effects of masker pulse trains—indeed, the available evidence cited earlier indicates that high pulse rates result in increases in adaptation in auditory-nerve response patterns.

There are two plausible mechanisms for the decrease in the magnitude of a central component of forward masking with increasing pulse rate. One is that the magnitude of the masking provided by the stimulus is proportional to the number of spikes evoked in the auditory nerve near the end of the masker duration. At high pulse rates, the central component of masking would decline in proportion to the adaptation in the auditory nerve. Another possibility is that the central mechanism of forward masking is activated by ascending input only above a certain threshold of spike rate. At high pulse rates, the auditory nerve spike rate may fall below this threshold during the masking pulse train. In this case, the activation of the central component of masking would end prior to the offset of the stimulus. The data do not distinguish between these explanations.

Effect of level on gap detection and forward masking

At each pulse rate that we tested, gap thresholds decreased with increasing current levels. It is difficult to compare absolute stimulus levels between physiological and psychophysical results because of the lack of a measure of perceptual loudness in physiological studies. Nevertheless, human studies generally agree with our results, showing decreasing gap-detection thresholds with increasing stimulus level (Preece and Tyler 1989; Shannon 1989). To explain this finding, we examined growth of forward masking with stimulus level. The slope of the growth-of-masking functions increased with decreasing masker-probe delay. As gap durations shorten, the growth of response to the postgap stimulus should exceed the growth of masking only at higher stimulus levels.

We observed that growth of masking with current level was linear for electric stimulation at all time points after masker offset. These cortical results are consistent with other reports of linear growth of masking in the auditory nerve (Brown et al. 1996) as well as in human perception of cochlear-implant stimulation (Nelson and Donaldson 2001, 2002). Oxenham and Plack (2000) demonstrated with acoustic stimulation in normal-hearing listeners that the nonlinearities evident in the growth of masking with masker level, duration, and frequency were the result of peripheral nonlinearities at the basilar membrane, and that forward masking in normal hearing could be separated into a nonlinearity at the periphery followed by a linear response more centrally. We infer that measurements of forward masking evoked by cochlear implant stimuli provide a direct measure of the forward-masking processes central to the inner hair cell synapse, which is absent in deaf subjects.

Comparison with modulation detection

Sensitivity to AM of electric pulse trains is an alternative measure of temporal acuity that may be compared with gap detection. Prior comparisons of the sensitivity of cortical responses to acoustic gap-related amplitude-modulated stimuli have indicated that coding of these features may differ. Phillips and Hall (1990) showed that the precision of the first spike latency in auditory cortex of anesthetized cats is similar to that found peripherally in the auditory nerve, whereas phase-locking to ongoing modulated stimuli is low-pass filtered from the periphery to the cortex. Sinex and Chen (2000) demonstrated that there is no consistent relationship in the responses of neurons in the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus between sinusoidally modulated tones and artificial consonant–vowel pairs that vary in voice onset time. Recent electrophysiological studies of cortical modulation detection from our laboratory produced results that differed in several ways from the present gap-detection results (Middlebrooks 2008a). First, modulation sensitivity in that study decreased with increasing electric pulse rate. This is the opposite of the effect of pulse rate on gap-detection threshold. Second, the cortex was more sensitive to shallow modulation depths at lower stimulus levels, in contrast with the longer gap-detection thresholds observed at low current levels. Finally, modulation detection in anesthetized guinea pig cortex showed a significant dependence of limiting modulation frequency on cortical depth. Compared with thalamic afferent layers, extragranular layers showed phase-locking at lower limiting modulation frequencies and showed longer group delays. Those observations suggest the presence of an intracortical low-pass filtering mechanism. In contrast, our present results indicate that gap-detection thresholds are not significantly different over a 1.5-mm depth of the cortex that spans most of the layers in primary auditory cortex, including the input layers. These observations suggest that within-channel gap-detection thresholds are determined by subcortical mechanisms. The central auditory processing for gaps and modulation detection is distinct.

Conclusions

We observed enhanced temporal acuity in primary auditory cortex with increasing electric pulse rate. Gap-detection thresholds were shorter and recovery from forward masking was more rapid with higher pulse rates. Gap-detection thresholds shortened with increased stimulus level. Given the enhanced temporal acuity at high pulse rates observed in the present cortical study, the failure of higher pulse rates to enhance speech reception is puzzling. One possible explanation is that temporal acuity finer than normal hearing, such as we have seen in our gap-detection thresholds at 4,069 pps, could actually produce confusion of common speech cues. For example, voice onset times are similar in duration to across-channel gap-detection thresholds in normal-hearing listeners (Phillips et al. 1997). Perhaps temporal hyperacuity would disrupt discrimination of voiced and unvoiced stop consonants. Another possibility is that cochlear-implant performance is limited by sensitivity to AM of electric pulse trains. Sensitivity to amplitude-modulated signals has been shown to be important in speech recognition in both normal-hearing listeners responding to acoustic stimuli (Elliott and Theunissen 2009) and in cochlear-implant listeners (Fu 2002). This form of temporal processing is actually less sensitive at higher pulse rates.

We note that amplitude-modulated pulse trains may produce less adaptation in the auditory nerve than unmodulated pulse trains, even at high pulse rates. For that reason, the difference in adaptation to a long pulse train between low and high pulse rates might be less during typical use of a cochlear implant, compared with our physiological testing conditions.

When designing processor strategies it will be important to keep in mind that the central auditory system may interpret ascending cochlear stimulation differently at different pulse rates. Central contributions to forward-masking and gap-detection thresholds decrease with increasing pulse rate. The dependence of neural responses on carrier pulse rate occurs not only at the level of the processor and nerve but also higher in the auditory system.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grants R01 DC-04312, T32 DC-05356, and P30 DC-05188.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Wiler, Z. Onsan, and C. Ellinger for technical support and C.-C. Lee and B. Pfingst for providing helpful comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Brown CJ, Abbas PJ, Borland J, Bertschy MR. Electrically evoked whole nerve action potentials in Ineraid cochlear implant users: responses to different stimulating electrode configurations and comparison to psychophysical responses. J Speech Hear Res 39: 453–467, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busby PA, Clark GM. Gap detection by early-deafened cochlear-implant subjects. J Acoust Soc Am 105: 1841–1852, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M. Temporal mechanisms underlying recovery from forward masking in multielectrode-implant listeners. J Acoust Soc Am 105: 1853–1863, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M, Fu QJ, Shannon RV. Within-channel gap detection using dissimilar markers in cochlear implant listeners. J Acoust Soc Am 103: 2515–2519, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont JJ. Neural responses in primary auditory cortex mimic psychophysical, across-frequency-channel, gap-detection thresholds. J Neurophysiol 84: 1453–1463, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott TM, Theunissen FE. The modulation transfer function for speech intelligibility. PLoS Comp Biol 5: e1000302, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu QJ. Temporal processing and speech recognition in cochlear implant users. Neuroreport 13: 1635–1639, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin JJ, 3rd, Fu QJ. Effects of stimulation rate, mode and level on modulation detection by cochlear implant users. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 6: 269–279, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Swets JA. Signal Detection Theory and Psychophysics New York: Wiley, 1966 [Google Scholar]

- Grose JH, Buss E. Within- and across-channel gap detection in cochlear implant listeners. J Acoust Soc Am 122: 3651–3658, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich A, Alain C, Schneider B. Within- and between-channel gap detection in the human auditory cortex. Neuroreport 15: 2051–2056, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister J, Maxfield N, Pitt G. Cortical evoked response to gaps in noise: within-channel and across-channel conditions. Ear Hear 28: 862–878, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan NA, Creelman CD. Detection Theory: A User's Guide Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Mickey BJ, Middlebrooks JC. Representation of auditory space by cortical neurons in awake cats. J Neurosci 23: 8649–8663, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrooks JC. Effects of cochlear-implant pulse rate and inter-channel timing on channel interactions and thresholds. J Acoust Soc Am 116: 452–468, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrooks JC. Auditory cortex phase locking to amplitude-modulated cochlear implant pulse trains. J Neurophysiol 100: 76–91, 2008a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrooks JC. Cochlear-implant high pulse rate and narrow electrode configuration impair transmission of temporal information to the auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol 100: 92–107, 2008b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrooks JC, Snyder RL. Auditory prosthesis with a penetrating nerve array. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 8: 258–279, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Preuss P, Mitzdorf U. Functional anatomy of the inferior colliculus and the auditory cortex: current source density analyses of click-evoked potentials. Hear Res 16: 133–142, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DA, Donaldson GS. Psychophysical recovery from single-pulse forward masking in electric hearing. J Acoust Soc Am 109: 2921–2933, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DA, Donaldson GS. Psychophysical recovery from pulse-train forward masking in electric hearing. J Acoust Soc Am 112: 2932–2947, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PC, Smith ZM, Young ED. Wide-dynamic-range forward suppression in marmoset inferior colliculus neurons is generated centrally and accounts for perceptual masking. J Neurosci 28: 2553–2562, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen HB. Separable non-linear least squares [Online]. Department of Informatics and Mathematical Modeling, Technical University of Denmark http://www.imm.dtu.dk/∼hbn/publ/TR0001.ps [ 2009].

- Oxenham AJ, Plack CJ. Effects of masker frequency and duration in forward masking: further evidence for the influence of peripheral nonlinearity. Hear Res 150: 258–266, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfingst BE, Xu L, Thompson CS. Effects of carrier pulse rate and stimulation site on modulation detection by subjects with cochlear implants. J Acoust Soc Am 121: 2236–2246, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DP, Hall SE. Response timing constraints on the cortical representation of sound time structure. J. Acoust Soc Am 88: 1403–1411, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DP, Taylor TL, Hall SE, Carr MM, Mossop JE. Detection of silent intervals between noises activating different perceptual channels: some properties of “central” auditory gap detection. J Acoust Soc Am 101: 3694–3705, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomp R. Rate of decay of auditory sensation. J Acoust Soc Am 36: 277–282, 1964 [Google Scholar]

- Preece JP, Tyler RS. Temporal-gap detection by cochlear prosthesis users. J Speech Hear Res 32: 849–856, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein JT, Wilson BS, Finley CC, Abbas PJ. Pseudospontaneous activity: stochastic independence of auditory nerve fibers with electrical stimulation. Hear Res 127: 108–118, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon RV. Detection of gaps in sinusoids and pulse trains by patients with cochlear implants. J Acoust Soc Am 85: 2587–2592, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon RV. Forward masking in patients with cochlear implants. J Acoust Soc Am 88: 741–744, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon RV, Otto SR. Psychophysical measures from electrical stimulation of the human cochlear nucleus. Hear Res 47: 159–168, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinex DG, Chen GD. Neural responses to the onset of voicing are unrelated to other measures of temporal resolution. J. Acoust Soc Am 107: 486–495, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syka J, Suta D, Popelár J. Responses to species-specific vocalizations in the auditory cortex of awake and anesthetized guinea pigs. Hear Res 206: 177–184, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tasell DJ, Soli SD, Kirby VM, Widin GP. Speech waveform envelope cues for consonant recognition. J Acoust Soc Am 82: 1152–1161, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wieringen A, Wouters J. Gap detection in single- and multiple-channel stimuli by LAURA cochlear implantees. J Acoust Soc Am 106: 1925–1939, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Fenga Y, Yin S. The effect of gap-marker spectrum on gap-evoked auditory response from the inferior colliculus and auditory cortex of guinea pigs. Int J Audiol 45: 521–527, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Miller CA, Robinson BK, Abbas PJ, Hu N. Changes across time in spike rate and spike amplitude of auditory nerve fibers stimulated by electric pulse trains. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 8: 356–372, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]