Abstract

Cav2.1 channels regulate Ca2+ signaling and excitability of cerebellar Purkinje neurons. These channels undergo a dual feedback regulation by incoming Ca2+ ions, Ca2+-dependent facilitation and inactivation. Endogenous Ca2+-buffering proteins, such as parvalbumin (PV) and calbindin D-28k (CB), are highly expressed in Purkinje neurons and therefore may influence Cav2.1 regulation by Ca2+. To test this, we compared Cav2.1 properties in dissociated Purkinje neurons from wild-type (WT) mice and those lacking both PV and CB (PV/CB−/−). Unexpectedly, P-type currents in WT and PV/CB−/− neurons differed in a way that was inconsistent with a role of PV and CB in acute modulation of Ca2+ feedback to Cav2.1. Cav2.1 currents in PV/CB−/− neurons exhibited increased voltage-dependent inactivation, which could be traced to decreased expression of the auxiliary Cavβ2a subunit compared with WT neurons. Although Cav2.1 channels are required for normal pacemaking of Purkinje neurons, spontaneous action potentials were not different in WT and PV/CB−/− neurons. Increased inactivation due to molecular switching of Cav2.1 β-subunits may preserve normal activity-dependent Ca2+ signals in the absence of Ca2+-buffering proteins in PV/CB−/− Purkinje neurons.

INTRODUCTION

In cerebellar Purkinje neurons, voltage-gated Cav2.1 channels conduct P-type Ca2+ currents that trigger dendritic Ca2+ spikes (Llinás and Sugimori 1980a,b; Tank et al. 1988) and regulate repetitive firing (Walter et al. 2006; Womack and Khodakhah 2004). Cav2.1 is concentrated in the soma and dendrites of Purkinje neurons (Westenbroek et al. 1995) and mediates >90% of the whole cell voltage-gated Ca2+ current (Jun et al. 1999; McDonough et al. 1997; Mintz et al. 1992). Mouse mutations that inhibit P-type current density inhibit the frequency and precision of spontaneous firing (Donato et al. 2006; Walter et al. 2006) and increase intrinsic excitability in Purkinje neurons (Ovsepian and Friel 2008). Given the importance of Purkinje neurons in the control of motor function (Ito 1984), these cellular defects invariably cause ataxia (Sidman 1965; Snell 1955).

Like other Cav channels, Cav2.1 is directly modulated by Ca2+ ions that permeate the channel. During repetitive depolarizations, Cav2.1 channels undergo Ca2+-dependent facilitation followed by inactivation (Chaudhuri et al. 2005; DeMaria et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2000). These effects rely on Ca2+ binding to calmodulin, which interacts directly with the pore-forming Cav2.1 subunit (α12.1), and are absent for Cav2.1 Ba2+ currents (DeMaria et al. 2001; Lee et al. 1999). Ca2+-dependent inactivation, but not facilitation, is blunted by intracellular dialysis with Ca2+ chelators such as ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA) (Lee et al. 2000). These findings suggest that Ca2+-dependent facilitation depends on rapid, local Ca2+ signals through individual channels, whereas Ca2+-dependent inactivation relies on slower, global Ca2+ elevations supported by multiple neighboring channels (DeMaria et al. 2001; Liang et al. 2003; Soong et al. 2002).

The sensitivity of Ca2+-dependent inactivation to Ca2+ chelators has important implications for Cav2.1 channels in Purkinje neurons. These neurons have high endogenous Ca2+-buffering capacity due in part to the Ca2+-binding proteins parvalbumin (PV) and calbindin D-28k (CB) (Celio 1990; Fierro et al. 1998). By chelating free Ca2+, the two proteins and, more importantly, CB directly modulate the kinetics of synaptically evoked Ca2+ transients in Purkinje cell dendrites (Schmidt et al. 2003, 2007). PV and CB can also indirectly shape Ca2+ signals by controlling Ca2+ ions that are available for feedback regulation of Cav2.1. Like EGTA, coexpression of PV or CB with Cav2.1 in HEK293T cells can suppress Ca2+-dependent inactivation without affecting facilitation (Kreiner and Lee 2006). Therefore PV and CB may alter Ca2+ feedback regulation of Cav2.1 in Purkinje neurons.

To test this, we compared P-type currents in dissociated Purkinje neurons from wild-type (WT) mice and those lacking expression of PV and CB (PV/CB−/−). Voltage-dependent inactivation but not Ca2+-dependent inactivation was greater in PV/CB−/− than in WT neurons, which could be explained by down-regulation of the auxiliary Cavβ2a subunit. Our findings suggest a new role for Ca2+-binding proteins in maintaining Cav2.1 function and also suggest a compensatory mechanism by which Ca2+ homeostasis may be achieved in the absence PV and CB.

METHODS

Purkinje cell dissociation

Animal procedures complied with National Institutes of Health guidelines and were conducted under a protocol approved by Emory Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. PV and CB double-knockout mice (PV/CB−/−) were characterized previously (Vecellio et al. 2000) and maintained on the Sv129×C57/BL6 strain, which served as the WT group. Postnatal day 14 (P14) to P21 mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated. Sagittal cerebellar slices (400 μm) were cut on a vibratome and held in Tyrode solution (in mM: 150 NaCl, 4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH) at 34°C for 30 min before allowing them to cool to room temperature. Immediately prior to recording, slices were incubated for 10 min in papain (1 mg/ml; Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) dissolved in dissociation solution (in mM: 82 Na2SO4, 30 K2SO4, 5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH). Slices were then washed in Tyrode solution, placed in a fresh tube containing 1 ml Tyrode solution, and dissociated by gentle trituration through a series of fire-polished pipettes. Supernatant containing dissociated cells was placed on poly-l-lysine–coated coverslips for electrophysiological recording. Dissociated Purkinje neurons were readily distinguished from surrounding cells by their large, pear-shaped soma and dendritic stump.

HEK293T cell culture and transfection

HEK293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C under 5% CO2. Cells plated in 35-mm tissue-culture dishes were grown to 65–80% confluency and transfected with GenePORTER transfection reagent (Gene Therapy Systems, San Diego, CA), according to the manufacturer's protocol, with a 1:1 molar ratio of cDNAs for Ca2+ channel subunits: rat α12.1 (rbA isoform; Stea et al. 1994), β2a (Perez-Reyes et al. 1992) or β4 (Castellano et al. 1993), α2δ (Starr et al. 1991; total 5 μg), and 0.7 μg of a CD8 expression plasmid. At least 48 h after transfection, cells were incubated with CD8 antibody-coated microspheres (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) for identification of transfected cells for electrophysiological recording.

Electrophysiological recordings

Ca2+ or Ba2+ currents were recorded in transfected HEK293T cells and Purkinje neurons in whole cell patch-clamp configuration at room temperature. Extracellular recording solutions for HEK293T cells contained (in mM): 150 Tris, 1 MgCl2, and 10 CaCl2 or 10 BaCl2. Intracellular recording solutions contained (in mM): 130 N-methyl-d-glucamine, 60 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 2 Mg-ATP, and 0.5 EGTA. The pH of extracellular and intracellular recording solutions was adjusted to 7.3 with methanesulfonic acid. For voltage-clamp recordings of Purkinje neurons, extracellular solutions were optimized for stable whole cell recordings of Cav2.1 currents and contained (in mM): 155 tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA), 10 HEPES, 1 EGTA, and 10 CaCl2 or 2 or 10 BaCl2, adjusted to pH 7.4 with TEA-OH. Prior to recording, tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μM) and nimodipine (5 μM) were included in the extracellular recording solution to block Na+ and L-type Ca2+ currents, respectively. Intracellular solutions contained (in mM): 140 Cs methanesulfonate, 4 MgCl2, 0.5 EGTA, 9 HEPES, 14 creatine phosphate (Tris salt), 4 Mg adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP), and 0.3 Tris-GTP, adjusted to pH 7.4 with CsOH. For current-clamp recordings, Tyrode solution was used for the extracellular solution and the intracellular recording solution contained (in mM): 140 K-methyl sulfate, 10 KCl, 5 NaCl, 0.01 EGTA, 10 HEPES, and 2 Mg-ATP, adjusted to pH 7.4 with KOH. Electrode resistances in the recording solutions were typically 1–2 MΩ for Purkinje neurons and 2–4 MΩ for HEK293T cells. Reagents used for electrophysiological recordings were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Currents were recorded with an EPC-9 patch-clamp amplifier driven by PULSE software (HEKA Electronics, Lambrecht/Pfalz, Germany). Leak and capacitive transients were subtracted using a P4 protocol. Action potential (AP) waveforms were constructed by averaging traces corresponding to spontaneous APs recorded in current clamp from dissociated WT Purkinje neurons. The AP waveform was applied from a holding potential of −60 mV and had a half-width of 0.75 ms and peak amplitude of +25 mV for Purkinje neuron recordings. For transfected HEK293T cell recordings, the waveform was scaled to peak at +55 mV. Data were analyzed using routines written in IGOR Pro software (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). Averaged data represent the means ± SE. Statistical differences between groups were determined by Student's t-test. Current–voltage (I–V) curves were fit with the function: g(V − E)/{1 + exp[(V − V1/2)/k] + b}, where g is the maximum conductance, V is the test potential, E is the apparent reversal potential, V1/2 is the potential of half-activation, k is the slope factor, and b is the baseline. Significant differences between I–V curve values were determined with two-way repeated-measures ANOVA.

PCR analysis

For endpoint polymerase chain reaction (PCR), total RNA was isolated from cerebellar tissue using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Reverse transcription was performed on 2 μg RNA using random hexamers and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) at 42°C for 50 min. For isolated Purkinje neurons, the entire neuron was harvested by suction into an electrode containing intracellular recording solution. The tip of the pipette was then pressurized and broken to expel the cell into a tube containing reverse transcription reagents. Following overnight incubation at 40°C, the samples were used immediately or stored at −80°C. PCR reactions were performed with GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI) or Taq DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) and a Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY). PCR products were visualized by electrophoresis on 1–2% agarose gels prestained with ethidium bromide.

For quantitative PCR, pools of 5–10 Purkinje neurons were isolated for reverse transcription as described earlier. Oligonucleotide primers were designed to amplify approximately 100 basepair mouse sequences for Cavβ2a and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Amplification of a single band was confirmed initially by endpoint PCR and gel electrophoresis. Quantitative PCR was performed on reverse transcription (RT) reactions (2 μl) according to manufacturer's protocols with the DyNAmo HS SYBR Green qPCR kit (Finnzymes, Woburn, MA) and iCycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Samples were run in duplicate for 40 cycles [95°C for 15 min (hot start), 94°C for 20 s, 60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s]. Experiments were repeated at least three times using RNA collected from Purkinje neurons from different mice. Melt curve analysis revealed a single peak in SYBR green fluorescence, confirming amplification of a single product for each primer set. Efficiency of amplification was roughly 100% for each primer set and measured as [(10−1/k − 1) × 100], where k is the slope of the relationship between cycle threshold [C(t)] and dilution of the RT reaction. Relative change in WT compared with PV/CB−/− neurons was determined by the comparative C(t)[2−ΔΔC(t)] method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001), in which GAPDH was used as the internal control gene. For WT and PV/CB−/− neurons, ΔC(t) was determined as the difference in C(t) for the target (Cavβ2a) and C(t) for GAPDH. Percentage WT expression was then determined as: {[ΔC(t) for PV/CB−/−] − [ΔC(t) for WT]}× 100%. Primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table S1.1

RESULTS

Characterization of Ca2+-dependent inactivation and facilitation of P-type currents in Purkinje neurons

To allow for comparisons of neuronal P-type currents with Cav2.1 currents in transfected cells, recordings were made in whole cell patch configuration. Although this approach could cause dialysis of intracellular components, such as PV and CB, we did not observe significant differences in P-type current properties ≤20 min after membrane patch rupture. However, voltage protocols were initiated at the same time and run in the same order to minimize variability between cells. Although the absence of exogenous Ca2+ chelators in internal recording solutions might allow for maximal resolution of the effects of PV and CB, this approach did not allow stable whole cell recordings. However, the amount of EGTA in the intracellular recording solution was limited to 0.5 mM, which is permissive for Ca2+-dependent inactivation of Cav2.1 in transfected cells (DeMaria et al. 2001; Lee et al. 1999, 2000).

For our studies, we used Purkinje neurons from mice that were 14–21 days old. This age range was chosen as a compromise between the ability to obtain stable Ca2+ current recordings in young neurons and previous findings that mature expression levels of PV and CB are reached near P20 (Schwaller et al. 2002). Since Ca2+-dependent modulation of Cav2.1 has not been reported in mouse Purkinje neurons at this developmental stage, we first undertook a basic characterization of this process. To isolate P-type currents, whole cell patch-clamp recordings were conducted with extracellular Ca2+ (10 mM) and blockers of voltage-gated Na+ and K+ channels. Depolarizing steps were made from a holding voltage of −60 mV to minimize contribution of low-voltage–activated T-type currents in these cells (Raman and Bean 1999). Under these conditions, we observed large inward currents that did not inactivate significantly within the 50-ms test pulse. The currents were blocked about 80–90% on extracellular perfusion of the selective Cav2.1 blocker, ω-agatoxin type IVA (500 nM, Fig. 1 A). These properties were consistent with the P-type current in rat and mouse Purkinje neurons (Mintz et al. 1992; Raman and Bean 1999; Richards et al. 2007; Usowicz et al. 1992), which is mediated by Cav2.1 (Jun et al. 1999).

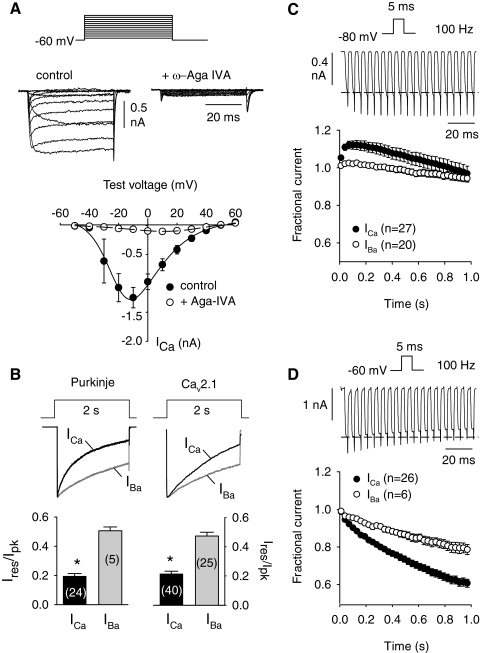

Fig. 1.

Ca2+-dependent inactivation of P-type currents in mouse cerebellar Purkinje neurons. A: current–voltage (I–V) relationships for a Ca2+ current (ICa) evoked by 50-ms steps from −60 mV to various voltages. Shown are representative current traces and voltage protocol (top) and I–V relationship (bottom) in cells before (control, filled circles) and after (+Aga-IVA, open circles) extracellular perfusion with ω-agatoxin-IVA (500 nM). Points represent means ± SE (n = 10). B: inactivation of P-type currents in Purkinje neurons and Cav2.1 (α12.1, β2a, α2δ) in transfected HEK293T cells. In Purkinje neurons, ICa and Ba2+ current (IBa) were evoked by 2-s pulses from −60 to −10 or −20 mV, respectively, and were evoked in transfected HEK293T cells by 2-s pulses from −80 to +10 or 0 mV, respectively. The −10-mV difference in test pulse used for IBa accounts for the shift in activation voltage when using Ba2+ as the charge carrier. Voltage protocol and current traces for ICa (black) and IBa (gray) are shown (top). Ires/Ipk (current amplitude at end of 2-s pulse normalized to peak current amplitude) is plotted below for Purkinje neurons (left) and transfected HEK293T cells (right). Parentheses indicate numbers of cells. *P < 0.01 by t-test. C: Ca2+-dependent facilitation during repetitive depolarizations in Cav2.1-transfected HEK293T cells. ICa and IBa were recorded during 5-ms steps from −80 to +10 mV (ICa) or 0 mV (IBa) delivered at 100 Hz. Fractional current represents test current amplitude normalized to the first in the train and is plotted against time. Every third data point is plotted. D: same as in C except that pulses were from −60 to 0 mV (ICa) or −10 mV (IBa) and applied to Purkinje neurons. In C and D, representative ICa and voltage protocols are shown above averaged data. Dashed line represents initial current amplitude.

We next compared inactivation of currents evoked by 2-s-step depolarizations using Ca2+ or Ba2+ as the permeant ion (Fig. 1B). Inactivation was measured as the current amplitude at the end of the test pulse normalized to the peak current amplitude (Ires/Ipk). With this protocol, Ca2+-dependent inactivation causes stronger inactivation (smaller Ires/Ipk) for Ca2+ currents (ICa) than for Ba2+ currents (IBa). By convention, inactivation of IBa is considered as proceeding by a purely voltage-dependent mechanism. As shown in Fig. 1B, P-type currents exhibited significant Ca2+-dependent inactivation similar to that of HEK293T cells transfected with cDNAs for Cav2.1 subunits (α12.1, β2a, α2δ).

In response to a train of 5-ms-step depolarizations, ICa in Cav2.1-transfected cells initially increases roughly 10–15% (Fig. 1C). This effect is not seen for IBa and represents Ca2+-dependent facilitation mediated by calmodulin (Lee et al. 2000). The same voltage protocol applied to mouse Purkinje neurons did not produce facilitation but only inactivation of ICa (Fig. 1D). Although the amplitude of facilitated ICa in Cav2.1-transfected cells declined to values approximating the initial (nonfacilitated) test current (Fig. 1C), ICa in Purkinje neurons inactivated roughly 60% by the end of the train (Fig. 1D). IBa also inactivated significantly more in Purkinje neurons than in Cav2.1-transfected cells during this protocol (Fig. 1, C and D), suggesting greater voltage-dependent inactivation in Purkinje neurons than that in transfected cells. Mechanistically, this could result from slower recovery from, or faster onset of, inactivation, which would increase the accumulation of inactivated channels during trains of depolarizations. Consistent with the latter possibility, inactivation of ICa in Purkinje neurons proceeded at a faster rate (τ = 0.77 ± 0.07, n = 24) than that in transfected cells (τ = 1.20 ± 0.06, n = 40; P < 0.001).

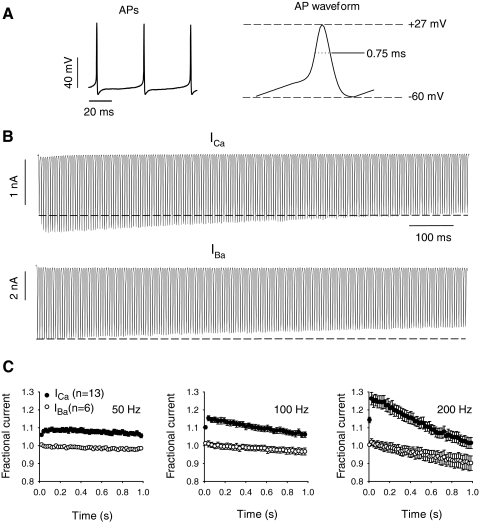

Voltage-dependent inactivation of the P-type current might obscure Ca2+-dependent facilitation during repetitive square-pulse stimuli since shorter depolarizations, such as with AP waveforms, have been shown to induce facilitation of P-type Ca2+ currents (Chaudhuri et al. 2005, 2007; Richards et al. 2007). Therefore we developed an AP waveform stimulus based on spontaneous APs measured first in current-clamp recordings (Fig. 2 A). At 200 Hz, AP waveforms consistently produced an initial facilitation of ICa (∼29 ± 4%) in Purkinje neurons, which decayed rapidly during the 1-s stimulus (Fig. 2, B and C). With the same protocol, IBa showed little facilitation (∼3 ± 2%), which may result from activity-dependent removal of Cav2.1 channels from G-protein inhibition (Brody et al. 1997; Park and Dunlap 1998). Facilitation of ICa was about tenfold greater than that for IBa, consistent with the magnitude of Ca2+-dependent facilitation in Cav2.1- transfected cells (Kreiner and Lee 2006; Lee et al. 2000). Facilitation of ICa was significantly greater with higher frequency stimulation (29 ± 4% for 200 Hz, 17 ± 2% for 100 Hz, and 11 ± 1% for 50 Hz; P < 0.001), which was not observed for IBa (3 ± 2% for 200 Hz, 2 ± 2% for 100 Hz, and 1 ± 1% for 50 Hz, P = 0.45; Fig. 2C). These results confirm that P-type currents undergo pronounced Ca2+-dependent facilitation in mouse Purkinje neurons, which would be greatest during periods of rapid firing.

Fig. 2.

Ca2+-dependent facilitation in Purkinje neurons during trains of action potential (AP) waveforms. A: spontaneous APs recorded in current-clamp (left) were used to construct an average AP waveform (right) with amplitude (+27 mV) and half-width (0.75 ms) indicated. B: representative ICa and IBa evoked by the AP waveform stimulus in A delivered at 200 Hz. Dashed line indicates current amplitude of the first pulse. C: increased Ca2+-dependent facilitation with higher frequency stimulation. Current responses to AP waveforms were measured at 50, 100, and 200 Hz. Fractional current represents test current amplitude normalized to the first in the train and plotted against time. For 100- and 200-Hz data, every third and fourth data point is plotted, respectively.

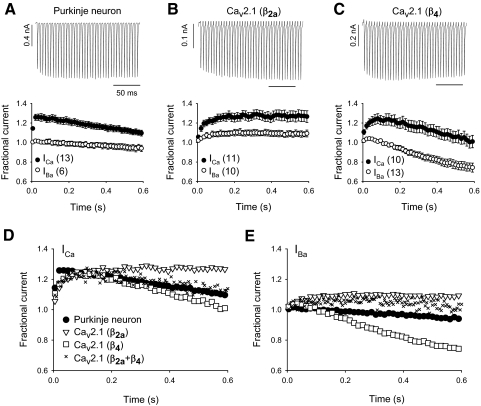

We next asked why voltage-dependent inactivation was stronger in Purkinje neurons than that in our Cav2.1-transfected cells, since this clearly influenced parameters for uncovering Ca2+-dependent facilitation (Fig. 1, C and D). We focused on the auxiliary Cavβ2a subunit, used in the transfected cell experiments, which is unique among Cavβ subunits in conferring slow voltage-dependent inactivation to Cav2.1 (De Waard and Campbell 1995; Stea et al. 1994). Of the four Cavβ variants (β1, β2, β3, β4,) detected in rodent cerebellum, Cavβ2a and Cavβ4 are most highly expressed in Purkinje neurons (Ludwig et al. 1997; Richards et al. 2007). Relative to Cavβ2a, Cavβ4 causes Cav2.1 to undergo greater voltage-dependent inactivation (Bourinet et al. 1999; Sokolov et al. 2000; Stea et al. 1994). Therefore the inactivating profile of P-type currents in mouse Purkinje neurons may result from the combined contribution of Cavβ2a and Cavβ4. To test this, we compared ICa and IBa in Purkinje neurons and HEK293T cells transfected with Cav2.1 channels containing β2a [Cav2.1(β2a)] or β4 [Cav2.1(β4)] (Fig. 3, A–C). In contrast to square-pulse depolarizations, which caused facilitated ICa to decay within 0.6 s in cells transfected with Cav2.1(β2a) (Fig. 1C), AP waveforms produced facilitation of ICa that remained maximal from about 0.2 to 0.6 s (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, maximal facilitation of ICa for Cav2.1(β4) (28 ± 6%) was not different from that of Cav2.1(β2a) (35 ± 5%, P = 0.42), but declined rapidly within 0.6 s (Fig. 3C). Thus the identity of the Cavβ isoform does not affect the maximal amount of Ca2+-dependent facilitation during AP waveform stimuli, but rather how long Ca2+-dependent facilitation lasts. The decline in the amplitude of the facilitated ICa in Cav2.1(β4)-transfected cells was likely due to the onset of voltage-dependent inactivation, which was apparent in comparing the rapid decay of IBa for Cav2.1(β4) with the maintained amplitude of IBa for Cav2.1(β2a) (Fig. 3, B and C). With Ca2+ or Ba2+ as the charge carrier, the neuronal P-type currents evoked by AP waveforms inactivated to a level intermediate to that for Cav2.1(β2a) and Cav2.1(β4) (Fig. 3, D and E). Coexpression of β2a and β4 in HEK293T cells yielded Cav2.1 currents that inactivated to an extent similar to that of P-type currents in Purkinje neurons (Fig. 3, D and E). However, the initial rise time of the facilitated ICa was considerably faster in Purkinje neurons than in HEK293T cells transfected with any combination of β subunits, perhaps due to the expression of distinct α12.1 splice variants in Purkinje neurons (Chaudhuri et al. 2005; Richards et al. 2007). Nevertheless, these findings suggest that voltage-dependent inactivation and, subsequently, the maintenance of Ca2+-dependent facilitation depend on the ratio of Cavβ2a and Cavβ4 subunits in Purkinje neurons.

Fig. 3.

Cavβ subunits influence the profile of Cav2.1 currents during AP stimuli. ICa and IBa were evoked by AP waveforms at 200 Hz. Representative ICa (top) and fractional current measured as in Fig. 2C (bottom) in Purkinje neurons (A) and HEK293T cells transfected with α12.1, α2δ, and β2a (B) or β4 (C). Parentheses indicate numbers of cells. Results in A–C and for cells cotransfected with β2a and β4 for ICa (D) and IBa (E) are superimposed on the same graph for comparison. For clarity, error bars were omitted in D and E and, for each graph, every third data point is plotted. For HEK293T cells cotransfected with both β2a and β4, results from exemplar cells are shown.

Comparison of P-type currents in WT and PV/CB−/− neurons

Having established that P-type currents in mouse Purkinje neurons undergo Ca2+-dependent inactivation and facilitation, we next evaluated the role of endogenous Ca2+ buffers in Purkinje neurons. Due to their high expression levels in Purkinje neurons, the Ca2+-binding proteins, PV and CB, may inhibit Ca2+-dependent inactivation in a manner similar to that of EGTA and BAPTA [1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid] (Lee et al. 2000). Since Ca2+-dependent facilitation of Cav2.1 is mediated by local Ca2+ signals not affected by EGTA and BAPTA (DeMaria et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2000; Liang et al. 2003), PV and CB should not affect Ca2+-dependent facilitation. If so, then Ca2+-dependent inactivation but not facilitation should be greater in Purkinje neurons lacking PV and CB. To test this, we compared P-type currents in Purkinje neurons isolated from WT and PV/CB−/− mice.

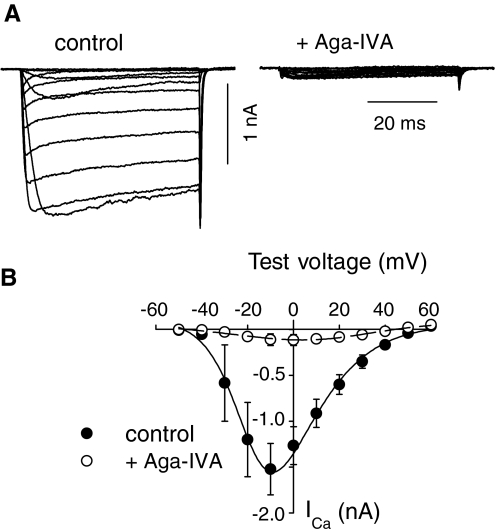

In general, P-type currents in WT and PV/CB−/− neurons showed similar activation properties, although the amplitude of ICa was generally greater in PV/CB−/− than that in WT neurons (Supplemental Table S2). There were no significant differences in cell capacitance (16.9 ± 0.6 pF for WT vs. 17.6 ± 0.7 pF for PV/CB−/−, P = 0.45) or the extent of block by ω-agatoxin IVA (90.0 ± 1.6% for WT vs. 84.4 ± 8.3% for PV/CB−/−; P = 0.20; Fig. 4). These results indicated that genetic deletion of PV and CB did not influence the contribution of Cav2.1 to the whole cell Ca2+ current in Purkinje neurons.

Fig. 4.

Characterization of P-type currents in PV/CB−/− Purkinje neurons. A: representative current ICa (A) and I–V relationship (B) in cells before (filled circles) and after (open circles) exposure to ω-agatoxin IVA (500 nM). Points represent means ± SE (n = 12). CB, calbindin D-28k; PV, parvalbumin.

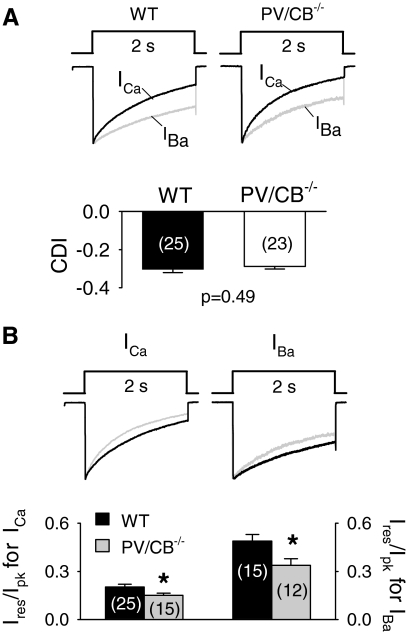

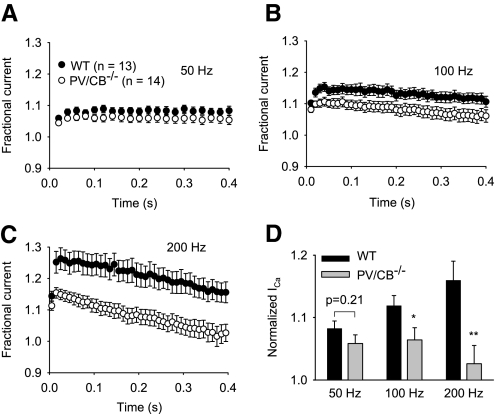

If PV and CB specifically attenuated Ca2+-dependent inactivation, we would expect an increase in inactivation of ICa in PV/CB−/− compared with that in WT neurons; the decay of IBa due to voltage-dependent inactivation should not be affected. However, we found that both ICa and IBa underwent greater inactivation in PV/CB−/− than that in WT neurons (Fig. 5, A and B). Since ICa inactivation contains both Ca2+-dependent and voltage-dependent components, we measured the difference between Ires/Ipk for ICa and IBa to isolate Ca2+-dependent inactivation and found that it was similar in WT and PV/CB−/− neurons (Fig. 5A). Together, these results indicate that voltage-dependent inactivation is increased in PV/CB−/− compared with that in WT neurons. Kinetic analyses showed significantly faster rates of inactivation for IBa in PV/CB−/− (τ = 1.05 ± 0.06, n = 12) than those in WT (τ = 1.69 ± 0.23, n = 15; P = 0.02) neurons, although there was no difference in inactivation rate for ICa (τ = 0.77 ± 0.07, n = 24, for WT vs. τ = 0.72 ± 0.05, n = 23, for PV/CB−/−; P = 0.5). Stronger voltage-dependent inactivation in PV/CB−/− neurons was particularly apparent at high stimulation frequencies (Fig. 6, A–D): P-type currents during 200-Hz AP waveforms decayed to initial levels within 0.4 s in PV/CB−/− neurons, whereas currents in WT neurons remained strongly facilitated (∼20%) at this time point (Fig. 6, C and D).

Fig. 5.

Increased voltage- but not Ca2+-dependent inactivation (CDI) of Cav2.1 currents in PV/CB−/− Purkinje neurons. A: ICa and IBa were evoked by 2-s pulses from −60 to 0 mV (ICa) or −10 mV (IBa) in wild-type (WT) and PV/CB−/− neurons. CDI represents the difference in Ires/Ipk for ICa and IBa in WT and PV/CB−/− neurons. B: comparison of Ires/Ipk for ICa and IBa (measured with 2 mM extracellular Ba2+) in WT (black traces) and PV/CB−/− neurons (gray traces). *P < 0.05 by t-test. Parentheses indicate numbers of cells.

Fig. 6.

Increased inactivation of P-type currents during high-frequency stimulation in PV/CB−/− Purkinje neurons. ICa was evoked by AP waveform stimuli given at 50 (A), 100 (B), or 200 Hz (C) in WT (filled circles) and PV/CB−/− (open circles) Purkinje neurons. Every other point is plotted for 200-Hz data. D: normalized ICa represents the grand average of current amplitude for the last 10 pulses (±SE) plotted against stimulation frequency for WT and PV/CB−/− neurons. **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05 compared with WT by t-test.

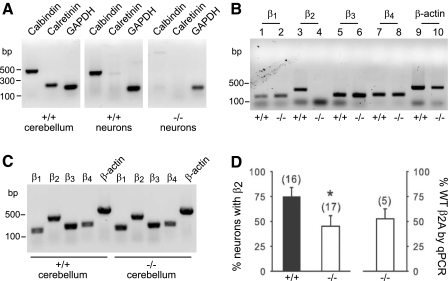

Because the stronger voltage-dependent inactivation in PV/CB−/− neurons could not be linked directly to the absence of Ca2+ buffers, we hypothesized that the differences in P-type currents in WT and PV/CB−/− neurons could have arisen from a compensatory change in Cav2.1 subunit expression. As alluded to in Fig. 3, a decrease in the ratio of Cavβ2a and Cavβ4 could boost the number of Cav2.1 channels undergoing strong voltage-dependent inactivation. We tested this possibility by PCR of isolated Purkinje neurons with primers specific for the different Cavβ subunits (Fig. 7, A–D). Because dissociated preparations of Purkinje neurons also contain a vast number of other cell types, mainly granule cells, we performed control experiments to ensure that we were isolating nucleic acids mainly from Purkinje neurons. In these experiments, calbindin D-28k mRNA (gene symbol: Calb1) was amplified from cere bellum and Purkinje neurons from WT mice but, as expected, not from PV/CB−/− neurons (Fig. 7A). In the cerebellum, calretinin (gene symbol: Calb2) is not expressed in Purkinje neurons but in unipolar brush cells, Lugaro cells, and predominantly in granule cells (Schwaller et al. 2002). As expected, calretinin mRNA was amplified only from total cerebellar RNA but not from RNA isolated from Purkinje neurons (Fig. 7A). These results validated the relative absence of contamination by granule cells in the samples of isolated Purkinje neurons.

Fig. 7.

Altered Cav2.1 subunit expression in PV/CB−/− Purkinje neurons. A: control experiment in which cerebellar tissue or pools of 5–10 Purkinje neurons from WT or PV/CB−/− mice were subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primers specific for calbindin D-28k (Calb1, CB), calretinin (Calb2, CR), or GAPDH. B: representative experiment showing amplification of all 4 β subunits in WT Purkinje neurons (n = 5) and the absence of β2 in PV/CB−/− neurons (n = 5). C: PCR analysis of Cavβ subunits (β1–β4) in cerebellar tissue from WT and PV/CB−/− mice. D: average results indicating percentage of individual neurons in WT and PV/CB−/− mice in which β2 was detected (left). Parentheses indicate numbers of cells. *P < 0.05 by t-test. Right: results from quantitative PCR from 5 to 10 Purkinje neurons using β2a-specific primers. Relative levels of β2a in WT and PV−/− neurons were determined as described in methods. Shown are averaged results from 5 independent experiments. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

As shown previously (Richards et al. 2007), all four Cavβ variants were detected in whole cerebellum (Fig. 7C) and Purkinje neurons from WT mice (Fig. 7B). Similar results were obtained in extracts from total cerebellum of PV/CB−/− mice (Fig. 7C), but not in the extracts from single isolated Purkinje neurons of null-mutant mice (Fig. 7B). Cavβ2 was amplified from most (75%) WT Purkinje neurons and in a significantly smaller fraction (<50%, P < 0.05) of PV/CB−/− Purkinje neurons (Fig. 7D). Of the Cavβ2 splice variants expressed in mouse Purkinje neurons (β2a–d), Cavβ2a is the most prominent (Richards et al. 2007). Our results suggested that Cavβ2a was specifically down-regulated in PV/CB−/− neurons below the threshold for detection in a one-step PCR protocol. We explored this possibility by quantitative PCR with Cavβ2a-specific primers (Supplemental Table S1). Because initial efforts to perform quantitative PCR with individual Purkinje neurons yielded inconsistent results, pools of 5–10 Purkinje neurons were analyzed with GAPDH as an internal reference. Consistent with the single-cell analyses, these experiments indicated levels of Cavβ2a in PV/CB−/− neurons that were only 53 ± 8% of that in WT Purkinje neurons (Fig. 7D). The nearly twofold decrease in Cavβ2a in PV/CB−/− neurons may therefore contribute to increased voltage-dependent inactivation of P-type currents in these neurons (Fig. 5B).

No differences in spontaneous firing properties in WT and PV/CB−/− neurons

Similar to their behavior in vivo, acutely isolated Purkinje neurons fire spontaneous APs that are driven primarily by voltage-gated Na+ channels (Raman and Bean 1999). However, Cav2.1 channels can regulate this process through selective coupling to Ca2+-activated (KCa) K+ channels. By conducting Ca2+ signals that activate KCa channels, Cav2.1 channels control the afterhyperpolarization (AHP) and, subsequently, the spontaneous firing rate in Purkinje neurons (Edgerton and Reinhart 2003; Walter et al. 2006; Womack and Khodakhah 2002; Womack et al. 2004). To understand the physiological consequences of our findings, we asked whether increased voltage-dependent inactivation of P-type currents might affect spontaneous firing in PV/CB−/− Purkinje neurons.

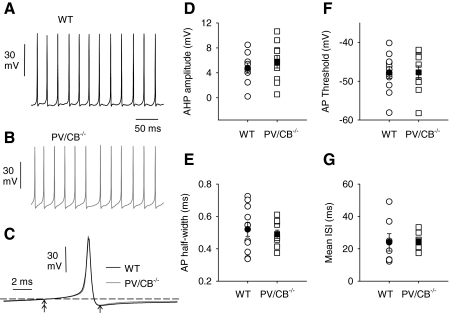

At first glance, limited Ca2+ influx due to faster inactivation of Cav2.1 channels might inhibit KCa contribution to the AHP such that the spontaneous firing rate would be faster in PV/CB−/− neurons relative to that in WT. However, as endogenous Ca2+ buffers, PV and particularly the fast buffer CB could normally limit coupling between Cav2.1 Ca2+ signals and KCa channels. In this case, one would expect that in PV/CB−/− neurons, spontaneous firing might be slower than that in WT due to stronger KCa-mediated AHPs. On the other hand, the molecular switch to Cav2.1 channels that undergo stronger voltage-dependent inactivation in PV/CB−/− neurons might offset aberrant KCa activation, such that net excitability is unaltered. To test these possibilities, we compared spontaneous firing in isolated WT and PV/CB−/− Purkinje neurons in current-clamp recordings with physiological solutions at room temperature. Under these conditions, nearly all Purkinje neurons from WT and PV/CB−/− neurons fired spontaneously in the absence of injected current. There were no significant differences in AHP amplitude or other parameters of spontaneous APs in WT and PV/CB−/− neurons (Fig. 8, A–F). The mean interspike interval for WT and PV/CB−/− neurons was not significantly different (Fig. 8G), which indicated a similar firing rate in neurons from the two genotypes. We conclude that spontaneous firing of isolated Purkinje neurons is not perturbed in PV/CB−/− neurons, which may be due in part to compensatory functional changes in Cav2.1.

Fig. 8.

No differences in spontaneous APs in WT and PV/CB−/− Purkinje neurons. Spontaneous APs were recorded from (A) WT and (B) PV/CB−/− neurons in current clamp without injected current. C: average AP waveform for WT (black trace, n = 11) and PV/CB−/− (gray trace, n = 10) neurons. For each neuron, averages are from all APs recorded in 10 consecutive sweeps of 500-ms duration. D–G: parameters for spontaneous APs in WT (circles) and PV/CB−/− (squares) neurons. Afterhyperpolarization (AHP) amplitude (D) was determined as the difference between the membrane potential measured 5 ms before the AP peak (double arrows in C) and the minimum membrane potential after the AP peak (single arrow in C). AP half-width (E) represents the duration of the AP at half-maximal amplitude from the threshold membrane potential. AP threshold (F) was measured at 5–15% of the tangential slope of the threshold depolarization. Mean interspike interval (ISI, G) is the average duration between peaks of the APs. Each symbol represents averaged data recorded as in A from one Purkinje neuron. Population averages are indicated with filled symbol (±SE).

DISCUSSION

Our results reveal multiple mechanisms governing the behavior of P-type currents in Purkinje neurons. First, P-type currents undergo Ca2+-dependent inactivation and facilitation, qualitatively similar to calmodulin-mediated regulation of recombinant Cav2.1 channels. Second, the inactivating profile of P-type currents during trains of AP stimuli may depend on the relative expression levels of different Cavβ subunits. Third, the Ca2+-binding proteins PV and CB are required for maintaining the normal properties of the P-type current. Multifaceted regulation of Cav2.1 in Purkinje neurons may ensure the temporal precision of Ca2+ signals required for the control of motor coordination.

Ca2+-dependent inactivation and facilitation of Cav2.1 in Purkinje neurons

Although the molecular details underlying Cav2.1 modulation by Ca2+/calmodulin have been elucidated at the atomic level (Kim et al. 2008; Mori et al. 2008), the prevalence of Ca2+ feedback regulation of Cav2.1 in neurons is less clear. Ca2+-dependent inactivation and facilitation were described for P-type currents in presynaptic terminals at the Calyx of Held (Cuttle et al. 1998; Forsythe et al. 1998) but were less robust for P/Q-type currents in chromaffin cells (Wykes et al. 2007). In rat Purkinje neurons, it was shown that P-type currents undergo Ca2+-dependent facilitation, whereas Ca2+-dependent inactivation was highly variable between cells (Chaudhuri et al. 2005). Ca2+-dependent inactivation was measurable in most of the mouse Purkinje neurons in our study (Figs. 1B and 5), which may be due to a species- or age-related difference in Cav2.1 properties since we used older mice (14 to 21 days old) rather than young (6 to 10 days old) rats as in the previous study. Considering the net hyperpolarizing function of P-type Ca2+ currents through coupling to KCa channels (Edgerton and Reinhart 2003; Llinás and Sugimori 1980b; Raman and Bean 1999; Womack et al. 2004), Ca2+-dependent inactivation of Cav2.1 may limit Ca2+ signals that would otherwise constrain the potential of Purkinje neurons to fire at high rates.

Our findings that Ca2+-dependent facilitation of the P-type current in Purkinje neurons increases with spike frequency (Fig. 2C) are consistent with previous work in rat and mouse (Chaudhuri et al. 2005; Richards et al. 2007). Mechanistically, Ca2+-dependent facilitation results from enhanced channel open probability due to Ca2+-dependent conformational changes in calmodulin associated with Cav2.1 (Chaudhuri et al. 2007). This process may be intrinsically favored by repetitive depolarizations. Alternatively, high-frequency AP trains may somehow derepress Ca2+-dependent facilitation of the P-type current. The presence of an endogenous inhibitor of Ca2+-dependent facilitation was suggested from findings that intracellular perfusion of Purkinje neurons with recombinant calmodulin significantly increased Ca2+-dependent facilitation of the P-type current (Chaudhuri et al. 2005). High-frequency stimulation may enhance the effectiveness of endogenous calmodulin in competing with this inhibitor, thus leading to greater Ca2+-dependent facilitation for currents evoked by 200- than that by 100- and 50-Hz AP stimuli (Fig. 2C). In Purkinje neurons, increased recruitment of Cav2.1 by high-frequency stimulation may underlie activity-dependent Ca2+ signals required for Cav2.1 coupling to activation of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (Mizutani et al. 2008) and depolarization-activated Ca2+ signals leading to long-term depression (Jin et al. 2007).

Altered Cav2.1 properties and Ca2+ homeostasis in PV/CB−/− Purkinje neurons

PV and CB act as mobile Ca2+ buffers, which can significantly alter the kinetics of Ca2+ signals in Purkinje neurons (Schmidt et al. 2003, 2007). We could not directly test whether PV and CB, like EGTA (Lee et al. 1999, 2000), might temper Ca2+-dependent inactivation of the P-type current since the intrinsic properties of the P-type current differed in WT and PV/CB−/− Purkinje neurons (Figs. 5 and 6). Decreased contribution of Cavβ2A subunits may permit greater voltage-dependent inactivation of P-type currents mediated by other Cavβ subunits in PV/CB−/− neurons (Fig. 7, B and D). However, this interpretation does not rule out the involvement of other mechanisms. Multiple α12.1 splice variants have been detected in Purkinje neurons (Bourinet et al. 1999). Some have variable cytoplasmic C-terminal domains (Kanumilli et al. 2006; Richards et al. 2007; Tsunemi et al. 2002), which can increase voltage-dependent inactivation of Cav2.1 (Krovetz et al. 2000). Increased expression of these variants could also contribute to the more strongly inactivating P-type currents in PV/CB−/− neurons.

Since PV and CB reach their mature expression levels in mice near P20 (Schwaller et al. 2002), it is tempting to speculate that increased Cav2.1 channel inactivation may be characteristic of the immature Purkinje neuron. Consistent with this possibility, in situ hybridization studies show that mRNA for Cavβ2 subunits is weak in P1 rat Purkinje neurons, but increase from P7 to P14 (Tanaka et al. 1995). Interestingly, α12.1 splice variants that undergo greater Ca2+-dependent facilitation also increase in expression in rat Purkinje neurons during this age range (Chaudhuri et al. 2005). Developmental up-regulation of Cav2.1 subunits producing less inactivation and greater facilitation may increase the gain of Ca2+ signals because Ca2+ buffering strength increases due to the onset of PV and CB expression.

Although the spontaneous Purkinje cell firing properties were not different for WT and in PV/CB−/− mice in vitro (Fig. 8), the firing rate of single spikes from Purkinje neurons in vivo are higher in PV/CB−/− (∼70 Hz) than that in WT mice (∼45 Hz) (Servais et al. 2005). This difference may result from the influence of dendritic ion channels and synaptic inputs present in vivo that would not be retained in our in vitro recordings of dissociated Purkinje neurons. However, at the behavioral level, elimination of PV and CB results in only minor alterations in locomotor activity and coordination, not detectable in mice maintained under standard housing conditions (Bouilleret et al. 2000; Farre-Castany et al. 2007). In contrast to the severe ataxia exhibited by mice with loss-of-function mutations in the Cav2.1 α1-subunit (Pietrobon 2005), the relatively modest motor phenotype in PV/CB−/− mice may result from recruitment of multiple homeostatic mechanisms. The volume of mitochondria—organelles with a high Ca2+ uptake capacity, yet rather slow Ca2+ uptake kinetics—is increased selectively in a subplasmalemmal zone in Purkinje cells deficient for PV (Chen et al. 2006). In addition, the volume and length of dendritic spines are increased in Purkinje neurons from mice lacking CB (Vecellio et al. 2000). Together with Cav2.1 channels undergoing greater inactivation, these morphological changes may help Purkinje neurons cope with activity-dependent increases in Ca2+ that might otherwise degrade their information-encoding potential.

Our results are the first to demonstrate alterations in Cav2.1 channels as a consequence of loss of PV and CB. In addition to Purkinje neurons, PV and CB are highly expressed in distinct populations of interneurons (Celio 1990), where their expression is reduced following seizure activity (Kim et al. 2006; Magloczky et al. 1997). Modification of Cav2.1 properties through molecular switching of α12.1 splice variants and β subunits may represent a general mechanism to protect neurons against aberrant Ca2+ signaling and pathological Ca2+ overloads.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-NS-044922 and R01-DC-009433 to A. Lee, F31-NS-04975 to L. Kreiner, and S11-NS-055883 to M. Benveniste; American Heart Association and Israel Binational Science Foundation grants to A. Lee; and Swiss National Science Foundation Grants 3100A0-100400/1 and 310000-113518/1 to B. Schwaller.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. T. Snutch and E. Perez-Reyes for cDNAs; T. Grieco and I. Raman for advice on Purkinje neuron dissociation; and Dr. Frank Gordon for advice on statistical analyses.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental data.

REFERENCES

- Bouilleret V, Schwaller B, Schurmans S, Celio MR, Fritschy JM. Neurodegenerative and morphogenic changes in a mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy do not depend on the expression of the calcium-binding proteins parvalbumin, calbindin, or calretinin. Neuroscience 97: 47–58, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourinet E, Soong TW, Sutton K, Slaymaker S, Mathews E, Monteil A, Zamponi GW, Nargeot J, Snutch TP. Splicing of alpha 1A subunit gene generates phenotypic variants of P- and Q-type calcium channels. Nat Neurosci 2: 407–415, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody DL, Patil PG, Mulle JG, Snutch TP, Yue DT. Bursts of action potential waveforms relieve G-protein inhibition of recombinant P/Q-type Ca2+ channels in HEK 293 cells. J Physiol 499: 637–644, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano A, Wei X, Birnbaumer L, Perez-Reyes E. Cloning and expression of a neuronal calcium channel β subunit. J Biol Chem 268: 12359–12366, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio MR. Calbindin D-28k and parvalbumin in the rat nervous system. Neuroscience 35: 375–475, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri D, Alseikhan BA, Chang SY, Soong TW, Yue DT. Developmental activation of calmodulin-dependent facilitation of cerebellar P-type Ca2+ current. J Neurosci 25: 8282–8294, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri D, Issa JB, Yue DT. Elementary mechanisms producing facilitation of Cav2.1 (P/Q-type) channels. J Gen Physiol 129: 385–401, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Racay P, Bichet S, Celio MR, Eggli P, Schwaller B. Deficiency in parvalbumin, but not in calbindin D-28k upregulates mitochondrial volume and decreases smooth endoplasmic reticulum surface selectively in a peripheral, subplasmalemmal region in the soma of Purkinje cells. Neuroscience 142: 97–105, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuttle MF, Tsujimoto T, Forsythe ID, Takahashi T. Facilitation of the presynaptic calcium current at an auditory synapse in rat brainstem. J Physiol 512: 723–729, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaria CD, Soong T, Alseikhan BA, Alvania RS, Yue DT. Calmodulin bifurcates the local Ca2+ signal that modulates P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. Nature 411: 484–489, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Waard M, Campbell KP. Subunit regulation of the neuronal α1A Ca2+ channel expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol 485: 619–634, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato R, Page KM, Koch D, Nieto-Rostro M, Foucault I, Davies A, Wilkinson T, Rees M, Edwards FA, Dolphin AC. The ducky(2J) mutation in Cacna2d2 results in reduced spontaneous Purkinje cell activity and altered gene expression. J Neurosci 26: 12576–12586, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgerton JR, Reinhart PH. Distinct contributions of small and large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels to rat Purkinje neuron function. J Physiol 548: 53–69, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farre-Castany MA, Schwaller B, Gregory P, Barski J, Mariethoz C, Eriksson JL, Tetko IV, Wolfer D, Celio MR, Schmutz I, Albrecht U, Villa AE. Differences in locomotor behavior revealed in mice deficient for the calcium-binding proteins parvalbumin, calbindin D-28k or both. Behav Brain Res 178: 250–261, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierro L, DiPolo R, Llano I. Intracellular calcium clearance in Purkinje cell somata from rat cerebellar slices. J Physiol 510: 499–512, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe ID, Tsujimoto T, Barnes-Davies M, Cuttle MF, Takahashi T. Inactivation of presynaptic calcium current contributes to synaptic depression at a fast central synapse. Neuron 20: 797–807, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M. The Cerebellum and Neural Control, edited by Ito M. New York: Raven, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Kim SJ, Kim J, Worley PF, Linden DJ. Long-term depression of mGluR1 signaling. Neuron 55: 277–287, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun K, Piedras-Renteria ES, Smith SM, Wheeler DB, Lee SB, Lee TG, Chin H, Adams ME, Scheller RH, Tsien RW, Shin H-S. Ablation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channel currents, altered synaptic transmission, and progressive ataxia in mice lacking the α1A-subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 15245–15250, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanumilli S, Tringham EW, Payne CE, Dupere JR, Venkateswarlu K, Usowicz MM. Alternative splicing generates a smaller assortment of CaV2.1 transcripts in cerebellar Purkinje cells than in the cerebellum. Physiol Genomics 24: 86–96, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EY, Rumpf CH, Fujiwara Y, Cooley ES, Van Petegem F, Minor DL., Jr Structures of CaV2 Ca2+/CaM-IQ domain complexes reveal binding modes that underlie calcium-dependent inactivation and facilitation. Structure 16: 1455–1467, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JE, Kwak SE, Kim DS, Won MH, Kwon OS, Choi SY, Kang TC. Reduced calcium binding protein immunoreactivity induced by electroconvulsive shock indicates neuronal hyperactivity, not neuronal death or deactivation. Neuroscience 137: 317–326, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner L, Lee A. Endogenous and exogenous Ca2+ buffers differentially modulate Ca2+-dependent inactivation of Cav2.1 Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem 281: 4691–4698, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krovetz HS, Helton TD, Crews AL, Horne WA. C-Terminal alternative splicing changes the gating properties of a human spinal cord calcium channel alpha 1A subunit. J Neurosci 20: 7564–7570, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent facilitation and inactivation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci 20: 6830–6838, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Wong ST, Gallagher D, Li B, Storm DR, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Ca2+/calmodulin binds to and modulates P/Q-type calcium channels. Nature 399: 155–159, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, DeMaria CD, Erickson MG, Mori MX, Alseikhan B, Yue DT. Unified mechanisms of Ca2+ regulation across the Ca2+ channel family. Neuron 39: 951–960, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔC(T)) method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás R, Sugimori M. Electrophysiological properties of in vitro Purkinje cell dendrites in mammalian cerebellar slices. J Physiol 305: 197–213, 1980a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás R, Sugimori M. Electrophysiological properties of in vitro Purkinje cell somata in mammalian cerebellar slices. J Physiol 305: 171–195, 1980b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig A, Flockerzi V, Hofmann F. Regional expression and cellular localization of the α1 and β subunit of high voltage-activated calcium channels in rat brain. J Neurosci 17: 1339–1349, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magloczky Z, Halasz P, Vajda J, Czirjak S, Freund TF. Loss of calbindin-D28K immunoreactivity from dentate granule cells in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience 76: 377–385, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough SI, Mintz IM, Bean BP. Alteration of P-type calcium channel gating by the spider toxin omega-Aga-IVA. Biophys J 72: 2117–2128, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz IM, Venema VJ, Swiderek KM, Lee TD, Bean BP, Adams ME. P-type calcium channels blocked by the spider toxin omega-Aga-IVA. Nature 355: 827–829, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani A, Kuroda Y, Futatsugi A, Furuichi T, Mikoshiba K. Phosphorylation of Homer3 by calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II regulates a coupling state of its target molecules in Purkinje cells. J Neurosci 28: 5369–5382, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori MX, Vander Kooi CW, Leahy DJ, Yue DT. Crystal structure of the Cav2 IQ domain in complex with Ca2+/calmodulin: high-resolution mechanistic implications for channel regulation by Ca2+. Structure 16: 607–620, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovsepian SV, Friel DD. The leaner P/Q-type calcium channel mutation renders cerebellar Purkinje neurons hyper-excitable and eliminates Ca2+-Na+ spike bursts. Eur J Neurosci 27: 93–103, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, Dunlap K. Dynamic regulation of calcium influx by G-proteins, action potential waveform, and neuronal firing frequency. J Neurosci 18: 6757–6766, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E, Castellano A, Kim HS, Bertrand P, Baggstrom E, Lacerda AE, Wei XY, Birnbaumer L. Cloning and expression of a cardiac/brain beta subunit of the L-type calcium channel. J Biol Chem 267: 1792–1797, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobon D. Function and dysfunction of synaptic calcium channels: insights from mouse models. Curr Opin Neurobiol 15: 257–265, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman IM, Bean BP. Ionic currents underlying spontaneous action potentials in isolated cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci 19: 1664–1674, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards KS, Swensen AM, Lipscombe D, Bommert K. Novel CaV2.1 clone replicates many properties of Purkinje cell CaV2.1 current. Eur J Neurosci 26: 2950–2961, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H, Brown EB, Schwaller B, Eilers J. Diffusional mobility of parvalbumin in spiny dendrites of cerebellar Purkinje neurons quantified by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. Biophys J 84: 2599–2608, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H, Kunerth S, Wilms C, Strotmann R, Eilers J. Spino-dendritic cross-talk in rodent Purkinje neurons mediated by endogenous Ca2+-binding proteins. J Physiol 581: 619–629, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaller B, Meyer M, Schiffmann S. “New” functions for “old” proteins: the role of the calcium-binding proteins calbindin D-28k, calretinin and parvalbumin, in cerebellar physiology. Studies with knockout mice. Cerebellum 1: 241–258, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servais L, Bearzatto B, Schwaller B, Dumont M, De Saedeleer C, Dan B, Barski JJ, Schiffmann SN, Cheron G. Mono- and dual-frequency fast cerebellar oscillation in mice lacking parvalbumin and/or calbindin D-28k. Eur J Neurosci 22: 861–870, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman RL, Green MC, Appel S. Catalogue of the Neurological Mutants of Mice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1965 [Google Scholar]

- Snell GD. Ducky, a new second chromosome mutation in the mouse. J Hered 46: 27–29, 1955 [Google Scholar]

- Sokolov S, Weiss RG, Timin EN, Hering S. Modulation of slow inactivation in class A Ca2+ channels by beta-subunits. J Physiol 527: 445–454, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soong TW, DeMaria CD, Alvania RS, Zweifel LS, Liang MC, Mittman S, Agnew WS, Yue DT. Systematic identification of splice variants in human P/Q-type channel α12.1 subunits: implications for current density and Ca2+-dependent inactivation. J Neurosci 22: 10142–10152, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr TVB, Prystay W, Snutch TP. Primary structure of a calcium channel that is highly expressed in the rat cerebellum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 5621–5625, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stea A, Tomlinson WJ, Soong TW, Bourinet E, Dubel SJ, Vincent SR, Snutch TP. The localization and functional properties of a rat brain α1A calcium channel reflect similarities to neuronal Q- and P-type channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 10576–10580, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka O, Sakagami H, Kondo H. Localization of mRNAs of voltage-dependent Ca2+-channels: four subtypes of α1- and β-subunits in developing and mature rat brain. Mol Brain Res 30: 1–16, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tank DW, Sugimori M, Connor JA, Llinás RR. Spatially resolved calcium dynamics of mammalian Purkinje cells in cerebellar slice. Science 242: 773–777, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunemi T, Saegusa H, Ishikawa K, Nagayama S, Murakoshi T, Mizusawa H, Tanabe T. Novel Cav2.1 splice variants isolated from Purkinje cells do not generate P-type Ca2+ current. J Biol Chem 277: 7214–7221, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usowicz MM, Sugimori M, Cherksey B, Llinás R. P-type calcium channels in the somata and dendrites of adult cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuron 9: 1185–1199, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecellio M, Schwaller B, Meyer M, Hunziker W, Celio MR. Alterations in Purkinje cell spines of calbindin D-28k and parvalbumin knock-out mice. Eur J Neurosci 12: 945–954, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter JT, Alvina K, Womack MD, Chevez C, Khodakhah K. Decreases in the precision of Purkinje cell pacemaking cause cerebellar dysfunction and ataxia. Nat Neurosci 9: 389–397, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenbroek RE, Sakurai T, Elliott EM, Hell JW, Starr TV, Snutch TP, Catterall WA. Immunochemical identification and subcellular distribution of the α1A subunits of brain calcium channels. J Neurosci 15: 6403–6418, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womack MD, Chevez C, Khodakhah K. Calcium-activated potassium channels are selectively coupled to P/Q-type calcium channels in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci 24: 8818–8822, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womack MD, Khodakhah K. Active contribution of dendrites to the tonic and trimodal patterns of activity in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci 22: 10603–10612, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womack MD, Khodakhah K. Dendritic control of spontaneous bursting in cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neurosci 24: 3511–3521, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykes RC, Bauer CS, Khan SU, Weiss JL, Seward EP. Differential regulation of endogenous N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channel inactivation by Ca2+/calmodulin impacts on their ability to support exocytosis in chromaffin cells. J Neurosci 27: 5236–5248, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.