Abstract

Despite the existence of an active vaccination program, recently emerged strains of nephropathogenic infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) in Korea have caused significant economic losses in the poultry industry. In this study, we assessed the pathogenic and antigenic characteristics of a K-IIb type field strain of IBV that emerged in Korea since 2003, such as Kr/Q43/06. Specific pathogen free 1-week-old chickens exhibited severe respiratory symptoms (dyspnea) and nephropathogenic lesions (swollen kidneys with nephritis and urate deposits) following challenge with the recent IBV field strain. The antigenic relatedness (R value), based on a calculated virus neutralization index, of the K-IIb type field strain and K-IIa type strain KM91 (isolated in 1991) was 30%, which indicated that the recent strain, Kr/Q43/06, is a new variant that is antigenically distinct from strain KM91. This report is the first to document the emergence of a new antigenic variant of nephropathogenic IBV in chicken from Korea.

Keywords: antigenicity, infectious bronchitis, nephropathogenicity, variant

Introduction

Infectious bronchitis (IB), caused by the infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), is a highly contagious viral disease of chickens with a worldwide distribution [4]. It is characterized by respiratory symptoms, nephritis, poor performance and reduced egg reproduction [4].

Despite extensive vaccination, IB has been a perpetual problem in the Korean poultry industry since the disease was first reported in 1986 [7,9-11,16,17]. Recently, phylogenetic analysis revealed that Korean field isolates of IBV constitute at least three distinct phylogenetic types: K-I, K-II and K-III [10]. K-I type strains are native viruses associated with localized incidence in Korea, K-II type strains are closely related to nephropathogenic IBV strains isolated in China [19], and K-III type strains are closely related to enteric IBV variants of Chinese strains. In particular, the K-II type nephropathogenic IBV is associated with a high mortality rate, and has been the source of great economic losses in the poultry industry in Korea, despite the availability of a vaccine based on the KM91 strain of Korean nephropathogenic IBV [7,9-11,17].

Molecular epidemiological evidence suggests that K-II type QX-like viruses (K-IIb type) isolated since 2003 form a different cluster than those (K-IIa type) isolated prior to 2003 (e.g., strain KM91) [10]. Nevertheless, antigenic differences between K-IIa and K-IIb type viruses have yet to be fully investigated.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the pathogenic and antigenic characteristics of K-IIb type IBV strains currently circulating in Korea to determine whether available IBV vaccines based on K-IIa type strains will confer cross-protection against field IBV strains. Two Korean IBV strains, KM91 and Kr/Q43/06 (National Veterinary Research and Quarantine Service, Korea), were analyzed. Strain KM91 is a nephropathogenic K-IIa type virus that was isolated in early 1990s, and strain Kr/Q43/06 is a K-IIb type virus isolated in 2006 [10]. The H120 vaccine strain was used as a reference.

The pathogenicity of IBV strain Kr/Q43/06 was determined using specific pathogen free (SPF) 1-week-old layer type chickens (Lohmann, Germany). Ten chickens were inoculated with IBV Kr/Q43/06 (105.7EID50/dose) by eye drop inoculation. Five birds that served as the inoculation control group were inoculated with phosphate buffered saline. All birds were maintained in isolators with negative pressure and monitored daily for 14 days for overt clinical symptoms (depression, respiratory signs, diarrhea, etc.) and mortality. Six days post inoculation (dpi), all of the birds in the IBV group started to exhibit mild respiratory symptoms, including sneezing and rales. Clinical signs became more severe by 10 dpi, when most of the affected birds (7/10) exhibited severe depression and dyspnea, which continued to progress until the end of the experiment (14 dpi). Birds in the control group showed no clinical signs of IBV infection throughout the experimental period.

In the infected birds, gross lesions were mainly confined to the kidney, which was pale, swollen with interstitial nephritis and showed evidence of severe urate deposition. IBV was recovered from the trachea (90%, or 9/10) and kidney (80%, or 8/10) of infected birds by inoculating tissue homogenate into the allantoic cavity of 9 to 11 day-old SPF embryonated chicken eggs (Lohmann, Germany) using standard methods [5] and identified by dot-immunoblotting assay using monoclonal antibodies [17]. Control birds exhibited no pathological lesions in the kidney, and no evidence of viral load. These results demonstrated that strain Kr/Q43/06 is nephropathogenic in chickens.

Cross virus neutralization tests were performed using anti-sera against strains KM91, Kr/Q43/06 and H120 to determine the antigenic relationship between Kr/Q43/06 and KM91. IBV anti-sera were raised in our laboratory according to the immunization protocol of Gelb et al [5]. Anti-sera against homologous virus were used by checkerboard titration. Cross-virus neutralization tests were performed using SPF embryonated chicken eggs and the alpha method, as previously described [18]. Briefly, Serial dilutions of IBV are incubated with a standard dilution of serum (1/5 dilution), and then the serum-virus mixtures in each dilution were incubated into 5 SPF embryonated chicken eggs. Eggs were also inoculated with the corresponding titers of virus alone in parallel.

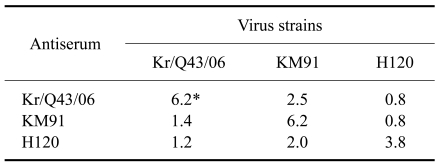

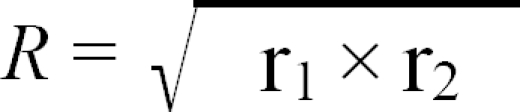

End-points were calculated by the Reed and Muench method [15]. A neutralization index (NI) was calculated, representing the difference (in logarithmic units) in viral titer between virus alone and the corresponding virus-antiserum mixture. An NI value of >4.5 indicated homologous strains, a value of 1.5~4.5 indicated heterologous strains, and a value of <1.5 was considered a different serotype. As shown in Table 1, strain Kr/Q43/06 was effectively neutralized by antiserum to the homologous strain (NI of 6.2). However, the NI for antisera to strains KM91 and H120 was 1.4 and 1.2, respectively, which indicated that antisera to strains KM91 and H120 were unable to effectively neutralize strain Kr/Q43/06. NI values were converted to antigenic relatedness (R value) using the following formula created by Archetti and Horsfall [1]:

Table 1.

Virus neutralization index (NI) for infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) strains Kr/Q43/06 and KM91

*NI was determined using the alpha method and SPF embryonated chicken eggs, and represents the log10 difference in titer between virus alone and virus-antiserum mixtures.

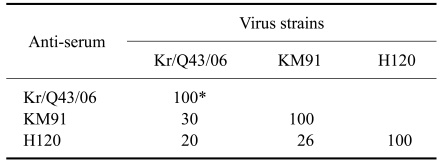

where r1 is the ratio of the NI value of virus 2 in the presence of antiserum to virus 1 (heterologous NI value) to the NI value of virus 1 in the presence of antiserum to virus 1 (homologous NI value); r2 is the ratio of the heterologous NI value of virus 1 to the homologous NI value of virus 2; and R defines the antigenic relatedness of the two viruses. For assessing the similarity of the two viruses, we used the criteria of Brooksby [3], as follows: an R value of 100% or close to 100% indicated antigenic identity between the two tested viruses; an R value >70% indicated little or no difference between the two viruses tested; an R value between 33% and 70% indicated a minor subtype difference; an R value between 11% and 32% indicated a major subtype difference; and an R value between 0% and 10% indicated different serotypes. The R value for strains Kr/Q43/06 and KM91 was 30%, which indicated that nephropathogenic strain Kr/Q43/06 is distantly related to strain KM91 (Table 2). Thus, strain Kr/Q43/06 represents a new variant that is antigenically distinct from strain KM91. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a new antigenic variant of nephropathogenic IBV in chickens from Korea.

Table 2.

Antigenic relatedness (R value) (%) of KIIa and KIIb type strains of IBV

In a previous study, phylogenetic analyses showed that type K-IIb IBV isolates are more closely related to strain QX than the K-IIa type strain KM91 at the level of the hyper-variable region of the S1 gene of IBV [10]. It is worth noting that the QX-like IBV is distributed worldwide, including in the Far East of Russia, Italy, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Japan [2,6,8,13,14]. Thus, K-IIb type strains of IBV might have emerged in Korea as a result of introduction from foreign countries rather than through immune pressure due to vaccination in the field, or recombination between field viruses. However, it remains unclear how this variant emerged in Korea. Interestingly, during viral surveillance in 2003 in Quangdong, China, a nephropathogenic strain of IBV was isolated from an asymptomatic teal (Anas) of the order Anseriformes [12]. This observation raises the possibility of widespread dissemination of IBV by wild birds, such as wild migratory ducks, as proposed by Bochkov et al [2]. While the role of wild birds in trans-boundary transmission of IBV has not been demonstrated, additional viral surveillance studies of wild birds, particularly wild ducks, are needed. In vivo cross protection studies should also be considered to determine whether currently available K-IIa type or Mass type IBV vaccines confer cross-protection against new K-IIb type variants. If currently available IBV vaccines do not provide cross-protection against new variant strains that emerge in the field, the development of alternative vaccines should be considered for the effective control of IB in Korea.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Veterinary Research and Quarantine Service of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Korea.

References

- 1.Archetti I, Horsfall FL., Jr Persistent antigenic variation of influenza A viruses after incomplete neutralization in ovo with heterologous immune serum. J Exp Med. 1950;92:441–462. doi: 10.1084/jem.92.5.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bochkov YA, Batchenko GV, Shcherbakova LO, Borisov AV, Drygin VV. Molecular epizootiology of avian infectious bronchitis in Russia. Avian Pathol. 2006;35:379–393. doi: 10.1080/03079450600921008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooksby JB. Variants and immunity: definitions for serological investigation. Int. Symp. On foot and mouth disease, variants and immunity, Lyon, France. Immunobiol Standard. 1967;8:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavangh D, Naqi S. Infectious bronchitis. In: Saif YM, Barnes HJ, Glisson JR, Fadly AM, McDougald LR, Swayne DE, editors. Diseases of Poultry. 11th ed. Ames: Iowa State University Press; 2003. pp. 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelb J, Jr, Weisman Y, Ladman BS, Meir R. S1 gene characteristics and efficacy of vaccination against infectious bronchitis virus field isolates from the United States and Israel (1996 to 2000) Avian Pathol. 2005;34:194–203. doi: 10.1080/03079450500096539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gough RE, Cox WJ, de B Welchman D, Worthington KJ, Jones RC. Chinese QX strain of infectious bronchitis virus isolated in the UK. Vet Rec. 2008;162:99–100. doi: 10.1136/vr.162.3.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jang JH, Sung HW, Song CS, Kwon HM. Sequence analysis of the S1 glycoprotein gene of infectious bronchitis viruses: identification of a novel phylogenetic group in Korea. J Vet Sci. 2007;8:401–407. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2007.8.4.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones RC, Worthington KJ, Capua I, Naylor CJ. Efficacy of live infectious bronchitis vaccines against a novel European genotype, Italy 02. Vet Rec. 2005;156:646–647. doi: 10.1136/vr.156.20.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JH, Song CS, Mo IP, Kim SH, Sung HW, Yoon HS. An outbreak of nephropathogenic infectious bronchitis in commercial pullets. Res Rep Rural Devel Admin. 1992;34:28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee EK, Jeon WJ, Lee YJ, Jeong OM, Choi JG, Kwon JH, Choi KS. Genetic diversity of avian infectious bronchitis virus isolates in Korea between 2003 and 2006. Avian Dis. 2008;52:332–337. doi: 10.1637/8117-092707-ResNote.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SK, Sung HW, Kwon HM. S1 glycoprotein gene analysis of infectious bronchitis viruses isolated in Korea. Arch Virol. 2004;149:481–494. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0225-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu S, Chen J, Chen J, Kong X, Shao Y, Han Z, Feng L, Cai X, Gu S, Liu M. Isolation of avian infectious bronchitis coronavirus from domestic peafowl (Pavo cristatus) and teal (Anas) J Gen Virol. 2005;86:719–725. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80546-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Kong X. A new genotype of nephropathogenic infectious bronchitis virus circulating in vaccinated and non-vaccinated flocks in China. Avian Pathol. 2004;33:321–327. doi: 10.1080/0307945042000220697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mase M, Tsukamoto K, Imai K, Yamaguchi S. Phylogenetic analysis of avian infectious bronchitis virus strains isolated in Japan. Arch Virol. 2004;149:2069–2078. doi: 10.1007/s00705-004-0369-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method for estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhee YO, Kim JH, Kim JH, Mo IP, Youn HS, Choi SH, Namgoong S. Outbreaks of infectious bronchitis in Korea. Korean J Vet Res. 1986;26:277–282. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song CS, Kim JH, Lee YJ, Kim SJ, Izumiya Y, Tohya Y, Jang HK, Mikami T. Detection and classification of infectious bronchitis viruses isolated in Korea by dot-immunoblotting assay using monoclonal antibodies. Avian Dis. 1998;42:92–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thayer SG, Beard CW. Serologic procedures. In: Swayne DE, Glisson JR, Jackwood MW, Pearson JE, Reed WM, editors. A Laboratory Manual for the Isolation and Identification of Avian Pathogens. 4th ed. Kennett Square: American Association of Avian Pathologists; 1998. pp. 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou J, Yu L, Hong J. Isolation, identification and pathogenicity of virus causing proventricular-type infectious bronchitis. Chinese J Anim Poult Infect Dis. 1998;20:62–65. [Google Scholar]