Abstract

Cytochrome c1 of Rhodobacter (Rba.) species provides a series of mutants which change barriers for electron transfer through the cofactor chains of cytochrome bc1 by modifying heme c1 redox midpoint potential. Analysis of post-flash electron distribution in such systems can provide useful information about the contribution of individual reactions to the overall electron flow. In Rba. capsulatus, the non-functional low-potential forms of cytochrome c1 which are devoid of the disulfide bond naturally present in this protein revert spontaneously by introducing a second-site suppression (mutation A181T) that brings the potential of heme c1 back to the functionally high levels, yet maintains it some 100 mV lower from the native value. Here we report that the disulfide and the mutation A181T can coexist in one protein but the mutation exerts a dominant effect on the redox properties of heme c1 and the potential remains at the same lower value as in the disulfide-free form. This establishes effective means to modify a barrier for electron transfer between the FeS cluster and heme c1 without breaking disulfide. A comparison of the flash-induced electron transfers in native and mutated cytochrome bc1 revealed significant differences in the post-flash equilibrium distribution of electrons only when the connection of the chains with the quinone pool was interrupted at the level of either of the catalytic sites by the use of specific inhibitors, antimycin or myxothiazol. In the non-inhibited system no such differences were observed. We explain the results using a kinetic model in which a shift in the equilibrium of one reaction influences the equilibrium of all remaining reactions in the cofactor chains. It follows a rather simple description in which the direction of electron flow through the coupled chains of cytochrome bc1 exclusively depends on the rates of all reversible partial reactions, including the Q/QH2 exchange rate to/from the catalytic sites.

Abbreviations: Eh, ambient redox potential; Em, redox midpoint potential; Em7, redox midpoint potential at pH 7; Em9, redox midpoint potential at pH 9; FeS, 2 iron–2 sulfur cluster; Q, ubiquinone; QH2, ubihydroquinone; Rba., Rhodobacter; WT, wild type

Keywords: Electron transfer, Cytochrome bc1, Complex III, Q cycle, Redox midpoint potential, Kinetic model

1. Introduction

Bioenergetic enzymes use chains of cofactors to transfer electrons over long distances and connect catalytic sites with substrate redox pools. In such systems, the overall direction of electron flow is a resultant of reversible partial reactions. When one, linearly organized chain is involved and the system behaves in purely electrochemical manner without any gating, the distribution of electrons among cofactors is relatively simple to predict based on equilibrium thermodynamic calculations. However complications arise when more than one chain is involved and the electron flow in one chain is somehow linked with the electron flow in the other chain or the group of chains. One of the prominent examples of this sort of arrangement is a two-chain assembly in cytochrome bc1 (complex III), a common component of respiratory and photosynthetic electron transfer systems.

In this enzyme a c-chain comprising high-potential cytochromes c1 and c and the 2 iron–2 sulfur cluster (FeS) and the b-chain comprising two low-potential hemes b (bL and bH) and quinone of the Qi site are linked together by the action of the centrally located quinone binding Qo site. This site catalyzes a reversible two-electron oxidation of hydroquinone with one electron delivered into the c-chain and the other electron delivered into the b-chain. This is an integral part of the Q cycle used by the enzyme to catalyze electron transfer between quinone and cytochrome c [1–3].

Despite intense studies, our knowledge about the mechanism of the Qo site catalysis and the way the two chains are connected is still not complete and thus remains a subject of intense debate. For the Qo site reaction, several variations of either sequential or concerted mechanisms are considered [4–9]. For the chain connection, a thermodynamic coupling without any gating, or a coupling with various combinations of long-range allosteric interactions between the chains are considered [4–8,10–15]. The latter ones often assume some level of control over the large-scale motion of the FeS head domain, which during the catalytic cycle moves between the states where the FeS cluster approaches the Qo site and the states where it approaches heme c1 [16]. Additional complications come from the observation that this enzyme functions as a dimer, and various types of intra-dimer interactions are also included in many of the proposed mechanisms [10,11,13,17,18]. The whole debate is intensified by the observation that under certain conditions cytochrome bc1 becomes vulnerable to superoxide production. This is considered to be a side reaction of the Q cycle with the most commonly accepted view that electrons leak on oxygen from a semiquinone formed in the Qo site [4,19–22]. How this occurs is not known, but highly desired to be known as it is expected to improve our knowledge about the mechanism of the Qo site action and to clarify some of the medically-related issues of radical production in living cells.

A convenient way to access experimentally certain electron transfer reactions of cytochrome bc1 is provided by membranes of purple photosynthetic bacteria where cytochrome bc1 can be light-activated through the allied photosynthetic reaction center. The electron flow through the two chains of cytochrome bc1 can be specifically manipulated by the use of inhibitors of catalytic Qo or Qi sites in combination with various site-directed mutations that purposely change some of the properties of cofactors [23]. Of those, mutations that target cytochrome c1 of Rhodobacter species turned out to be particularly useful, as they provided a whole series of variants which suitably alter electron transfer by modifying values of heme c1 midpoint potential [24–27].

One group of mutants includes the forms with mutations changing the sixth axial ligand to heme iron. In this case, an unusual tolerance of cytochrome c1 of Rba. sphaeroides to the alternations in the heme ligation pattern made it possible to obtain a whole range of mutants with modified potential of heme c1 which exposed the ultimate thermodynamic limits of operation of the cofactor chains in cytochrome bc1 [27]. The other group of mutants includes the low-potential forms of closely related Rba. capsulatus cytochrome c1 which are devoid of the disulfide bond naturally present in this species [26,28] (see Fig. 1) and in Rba. sphaeroides [29]. These non-functional forms revert spontaneously by introducing a second-site suppression (mutation A181T) that brings the potential of heme c1 back to the functionally high level yet maintains it some 100 mV lower from the native value. The revertants leave the disulfide bridge unrepaired [26].

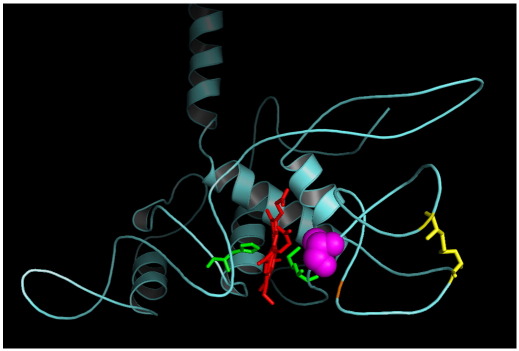

Fig. 1.

Ribbon model of the crystal structure of the heme domain of cytochrome c1 subunit of Rba. capsulatus cytochrome bc1[28]. Heme c1 (red sticks) is axially ligated by histidine and methionine (greens sticks). Position A181 (magenta spheres) is located within the sixth axial ligand domain. Position Y152 (orange line) is located between the two cysteine residues that form disulfide bond (yellow sticks).

In this work we report on some of the structural and redox properties of the mutant of cytochrome c1 of Rba. capsulatus in which the mutation A181T was introduced to the native protein containing all cysteine residues. We observe that the disulfide and A181T can coexist, but the mutation exerts a dominant effect on the redox properties of heme c1 and the potential remains at the same lower value as in the disulfide-free form. This established effective means to modify a barrier for electron transfer between the FeS cluster and heme c1 without breaking disulfide or changing the ligand to heme iron. We compared the flash-induced electron transfer in native and mutated cytochrome bc1 and found significant differences in the post-flash equilibrium distribution of electrons in the c-chain only when the connection of the chains with the quinone pool was interrupted at the level of either the Qo or the Qi site. To explain the results we developed a kinetic model which in our view improves the general understanding of electron flow through the coupled chains of cytochrome bc1.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Bacterial strains, plasmids, and general molecular genetic techniques

Rba. capsulatus strains and E. coli (HB101) were grown in MPYE (mineral-peptone-yeast-extract) and LB media, respectively, supplemented with appropriate antibiotics as needed [30]. Photosynthetic growth of Rba. capsulatus strains was tested on MPYE plates using anaerobic jars (GasPak System, BBL) at 30 °C under continuous light. Rba. capsulatus strains with mutated cytochrome bc1 were generated as described previously [31], using the genetic system which was a generous gift of Prof. F. Daldal (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA). The mutations A181T and A181T/Y152R were constructed by site directed mutagenesis. A 0.51 kb SphI/SfuI fragment of petC gene was amplified by PCR with the set of two primers ASUII-F: 5′-CTTCAGCTTCGAAGGGATCTTCG (SfuI site is shown in italic) and A181T-R: 5′-GGGCATGCGCGTCCAGCTGC (point mutation is shown in bold, SphI site is in italic). The template DNA for PCR was either pPET1 [31] or pPET1-cY152R [26], a derivative of pBR322 containing either a wild-type copy of petABC or a copy of petABC with a single mutation Y152R in petC, respectively. The resulting 0.51 kb PCR products containing either A181T or A181T/Y152R in petC were first exchanged with their wild-type counterparts in pPET1 using the restriction enzymes SphI/SfuI and then inserted into pMTS1 (the expression vector containing a copy of petABC) using the restriction enzymes SfuI/HindIII. The entire petC gene was sequenced to ensure that the constructs contained the desired mutation and no other mutations. The mutated variants of pMTS1 were introduced into MT-RBC1 strain (petABC-operon deletion background) via triparental crosses as described in ref. [31]. In each case, the presence of engineered mutations was confirmed by sequencing the plasmid DNA isolated from the mutated Rba. capsulatus strains.

2.2. Isolation of cytochrome bc1 and electrophoresis

The chromatophore membranes were prepared from semiaerobically grown cultures of Rba. capsulatus as described previously [31,32]. Membranes were solubilized with dodecyl maltoside and the purification of cytochrome bc1 by the ion-exchange chromatography was performed as described in ref. [32]. Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed as described in ref. [26]. Samples of protein were incubated under reducing conditions at 60 °C for 5 min prior to the loading on gels (15% linear separating gel was used) and the gels were stained with Coomassie blue. The presence of disulfide bridge in cytochrome c1 containing A181T was verified using the factor Xa cleavage assay as descried in detail in ref. [26] on the form that contained the cleavage site introduced by mutation Y152R.

2.3. Optical spectroscopy and redox potentiometry

Optical spectra for b- and c-type cytochromes were recorded using Shimadzu UV-2450 spectrophotometer. The difference spectra were obtained with samples that were first oxidized by an addition of a potassium ferricyanide (to a final concentration of 20 μM) and then reduced by using either sodium ascorbate (added to a final concentration of 2 mM) or a minimal amount of solid sodium dithionite. Chemical oxidation–reduction midpoint potentials titrations of hemes c in membranes or purified complexes were performed as described in ref. [33]. The titrations were performed in 50 mM MOPS (for pH 7), 50 mM Tris (for pH 9) containing 100 mM KCl, and redox mediators: tetrachlorohydroquinone, 2,3,5,6-tetramethyl phenylenediamine, 1,2-naphthoquinone-4-sulfonate, 1,2-naphthoquinone, phenazine methosulfate, phenazine ethosulfate, and duroquinone at concentration of 5–15 μM. The optical changes that accompanied redox potential change were recorded in the α-region (500–600 nm) and the redox midpoint potentials (Em) of hemes c were determined by fitting the 552–542 nm difference to an n = 1 Nernst equation with one or two components, for the measurements with isolated complexes or membranes, respectively.

2.4. Flash-induced electron transfer measurements

Flash-activated turnover kinetics of cytochrome bc1 were performed essentially as described in refs. [34–36], on a home-built double wavelength time-resolved spectrophotometer. The spectrophotometer consisted of a SP-20 Flash Lamp System (Rapp OptoElectronic, GmbH) and an optical assembly equipped with two H-20Vis monochromators (JY Horiba) (a generous gift of Prof. P. Leslie Dutton, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA) and the two 9828SB07 photomultipliers in QL30 housing (Electron Tubes). An activation of the sample and an acquisition of the data were controlled by a locally written program using the NI PXI-1042Q interface (National Instruments). The electronic assembly was designed by T. Oleś and J. Kozioł (Jagiellonian University). For the measurements, chromatophore membranes were suspended in appropriate buffer: 50 mM MES (for pH 6), 50 mM MOPS (for pH 7), or 50 mM Tris (for pH 9) containing 100 mM KCl, 3.5 μM valinomycin, and redox mediators: 7 μM 2,3,5,6-tetramethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine, 1 μM phenazine methosulfate, 1 μM phenazine ethosulfate, 5.5 μM 1,2-naphthoquinone, 5.5 μM 2-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone. The sample was poised at an ambient potential of 150 mV, 100 mV, or -20 mV for pH 6, 7, or 9, respectively. Transient cytochrome c and b reduction kinetics initiated by a short saturating flash (10 μs) from a xenon lamp were followed at 550–540 nm and 560–570 nm, respectively. Inhibitors antimycin A, myxothiazol, and stigmatellin were used at final concentrations of 7, 7 and 1.5 μM, respectively.

2.5. Kinetic model of flash-activated electron transfer

Simulation of flash-activated curves were performed using XPPAUT 5.85 [37] included in Ubuntu Linux 8.10. The model was built from a set of 28 differential equations, from which 24 describe the changes in the concentrations of particular states of cytochrome bc1 monomer (i.e., redox states of cofactors, occupancy of Qo site, position of the FeS head domain) and the remaining four equations describe the changes in the concentrations of substrates (i.e., quinone (Q), quinol (QH2) and cytochrome c). The equations were constructed taking into account the following assumptions: (1) molar ratio of total quinone to cytochrome bc1 monomer is 20:1, (2) single flash generates two oxidized molecules of cytochrome c per cytochrome bc1 monomer [38], (3) affinities of Q and QH2 to the Qo are equal, (4) all steps are reversible, (5) all reactions within a monomer are independent on each other and each monomer can work independently, (6) reduction of Q and oxidation of QH2 at the Qo site are both concerted. The individual reactions in the high-potential c-chain were taken for detailed calculations. The b-chain, for simplicity, was described by one equation, in which the presence or absence of inhibitors was expressed by variations in the time constants describing concerted electron transfer from QH2 to FeS and heme bL or from heme bL and FeS to Q at the Qo site. At the beginning of the simulations the concentrations of Q and QH2 were the same and all Qo sites of the cytochrome bc1 were occupied. The effect of change in the difference of potential between the FeS center and heme c1 was included in the time constants for electron transfer rates between FeS and heme c1 estimated using the equations of Moser and Dutton [39,40]. In these calculations, the distance of 11.4 Å between cofactors and reorganization energy of 0.7 eV were taken [41]. All remaining rate constants were adjusted to correctly reproduce the experimental curves. The simulated curves were obtained by numerical integration of the differential equations with XPPAUT using Gear's algorithm and the outputs were analyzed using home-written LabView program. The XPPAUT script used for simulations is included in Supplementary Material.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Structural and redox properties of the family of A181T (βXM) mutants

Earlier work has established two independent structural motifs that contribute to controlling the integrity of the heme binding pocket to raise the redox potential in cytochrome c1 of Rba. capsulatus [26]. The native protein employs, an uncommon for cytochromes c, disulfide anchoring of the extra loop (C144-C167) adjacent to the domain of the sixth axial ligand of heme iron (M183) (Fig. 1). The engineered disulfide-free protein (containing cysteine to alanine mutations at positions 144 and 167) has a loosened structure with the redox midpoint potential lowered to nonfunctional levels unless an additional suppressor mutation is present in the form of a β-branched amino acid two residues away from the heme-ligating methionine (A181T) (Fig. 1). With this mutation (considered as a part of a so called βXM motif, naturally present in many other cytochromes c) cytochrome c1 reaches back a functional range of high redox potential (Em7 = 227 mV). The value of the potential is, however, still lower by 100 mV from the value of native cytochrome c1 [26].

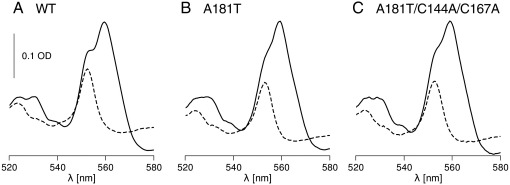

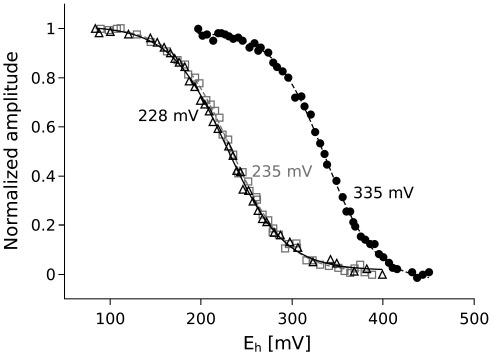

To test the effect of the presence of the βXM motif alone, we introduced A181T to the protein in which the cysteines at positions 144 and 167 were not changed. With this mutation, cytochrome bc1 is functional in vivo (PS+ phenotype) (Table 1) and the optical difference spectra of purified complexes have the ascorbate-reducible component at 552 nm reminiscent of the presence of high potential cytochrome c (Fig. 2, dashed line). The shape of the spectra of cytochrome bc1 fully reduced with dithionite (Fig. 2, solid line) immediately suggests some similarities between A181T and A181T/disulfide-free cytochrome c1: in both spectra the 552 nm component of cytochrome c1 is less separated, in comparison to the wild type, from the component at 560 nm corresponding to cytochromes b. Even more significantly, the redox midpoint potential of A181T cytochrome c1 has a very close value to that of A181T/disulfide-free cytochrome c1 (235 vs. 228 mV) which, again, is about 100 mV lower than in the wild-type (Table 1, Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Effect of A181T mutation on redox properties of cytochrome c1 with and without the presence of the disulfide bridge.

| PSa | Em7 isolatedb | Em membranesc | Disulfide bridge | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | + | 335 | 328(pH7) | + |

| A181T | + | 235 | 229(pH7); 223(pH9) | +d |

| A181T/C144A/C167A | + | 228 | ND | - |

Photosynthetic phenotype; + indicates photosynthetic growth ability.

Potential of heme c1 in isolated complexes.

Potential of heme c1 in membranes where titrations show an additional component of + 377 mV (cytochromes c2 and cy); (pH7) and (pH9) indicate pH for which a value of Em is given.

Based on the results of the factor Xa cleavage assay performed with a form containing the factor Xa cleavage site (A181T/Y152R).

Fig. 2.

Optical redox difference spectra of cytochrome bc1 isolated from wild type (A), A181T mutant (B) and A181T/C144A/C167A mutant (C). Solid and dashed lines correspond to dithionite minus ferricyanide and ascorbate minus ferricyanide spectra, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Potentiometric dark equilibrium titration of heme c1 in isolated wild-type cytochrome bc1 (closed black circles), A181T mutant (open grey squares) and A181T/C144A/C167A triple mutant (open black triangles). The titrations were performed at pH 7, and experimental data were fit to the Nernst equation for a one-electron couple. The Em values obtained are shown in the figure and also listed in Table 1.

This apparently dominant effect of mutation A181T on the redox properties of cytochrome c1 raises an interesting structural question as to how much the specific orientation of the loop regions reinforced by a reduced conformational flexibility of T181 [26] differs from the native structure. The most severe case would feature A181T not allowing the disulfide to form even with C144 and C167 present. To test this, we used a factor Xa cleavage assay (described in detail in ref. [26]) on a variant of A181T which contained a factor Xa cleavage site in the region between C144 and C167 (i.e., had additional mutation Y152R, see Fig. 1). The results (Fig. S1 in Supplementary Material) revealed that a disulfide bond does form in A181T/Y152R (and by extrapolation in A181T) indicating that the A181T mutation and the disulfide can coexist in one protein (Table 1). Thus, to explain the very same drop in the redox potential of both of A181T mutants (i.e., in disulfide-free and disulfide-containing form), one may speculate that those mutants adopt similar overall conformation which somehow differs from the native conformation, yet features the loop regions oriented in such a manner that disulfide bond is formable provided that C144 and C167 are present (i.e., the alanines at positions 144 and 167 in disulfide-free A181T mutant are in approximately the same orientation as the cysteines 144 and 167 in disulfide-containing A181T).

To what extent the A181T mutants differ structurally from the native cytochrome c1 and how this relates to the observed change in the redox potential requires further studies which are beyond the scope of this work. We focused on using the redox properties of A181T mutants as the effective means to unravel some of the mechanistic elements of electron transfer within the cofactor chains of cytochrome bc1. For this purpose we chose A181T mutant containing disulfide bond. Even though, as discussed earlier, all A181T mutants might adopt similar overall conformation, the possibility that it more resembles the native structure (i.e., structural “side effects” are minimized) is always higher in the disulfide-containing rather than disulfide-free form.

3.2. Light-induced electron transfer in wild type and A181T

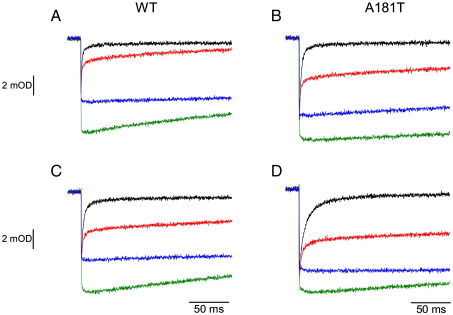

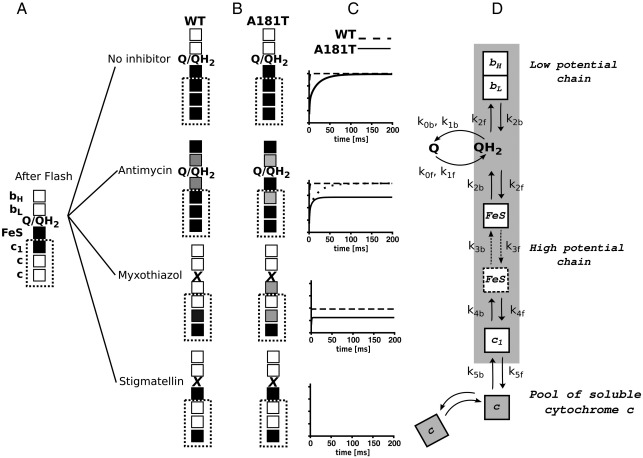

Fig. 4 compares kinetic transients of electron transfer in the c-chain of wild type cytochrome bc1 with those of A181T mutant. The characteristic and well-known traces recorded for the wild type at pH 7 and ambient potential of 100 mV (which maintains the Q pool half-reduced) include: the trace for the non-inhibited system, where the light-induced oxidation of cytochromes c is followed by a complete re-reduction phase (Fig. 4A, black); the trace with the Qi inhibitor antimycin present where cytochrome c re-reduction occurs but on the millisecond timescale is not completed (Fig. 4A, red); and the traces with two specific inhibitors of the Qo site, stigmatellin or myxothiazol (Fig. 4A, green or blue, respectively). The trace with stigmatellin reveals the full extent of flash-oxidized cytochrome c (in this case the FeS cluster is locked at the Qo site due to interactions with inhibitor and can not interact directly with cytochrome c1), while the trace with myxothiazol reveals the amount of cytochrome c that remains oxidized after initial reduction by the pre-reduced FeS cluster (in this case the FeS cluster is not locked at the Qo site and can interact with cytochrome c1); see description of myxothiazol and stigmatellin traces in ref. [42]. The rate of reduction of cytochrome c by the pre-reduced FeS cluster is faster than the time resolution of the method, thus in the presence of myxothiazol we only register the final level of oxidized cytochrome c which gives a smaller amplitude than the amplitude of oxidized cytochrome c recorded in the presence of stigmatellin. The corresponding traces of heme b oxidation/reduction are not shown; only the rate of heme b reduction in the presence of antimycin is reported in Table 2.

Fig. 4.

Flash-activated cytochrome c oxidation and re-reduction in chromatophores containing wild-type cytochrome bc1 (A, C) and the A181T mutant (B, D). Kinetic transients at 550–540 nm were recorded at pH 7 (A, B) or pH 6 (C, D) with the Q pool half-reduced, in the absence of inhibitors (black) and in the presence of antimycin (red), myxothiazol (blue) or stigmatellin (green).

Table 2.

Rates of flash-induced heme bH reduction in the presence of antimycin (s-1).

| pH | WT | A181T |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 566 | 386 |

| 7 | 1051 | 656 |

| 9 | 1791 | 1301 |

In the next parts, the difference in the level of the oxidized cytochrome c recorded in the presence of stigmatellin and the level of cytochrome c re-reduced in the presence of antimycin will be referred as “antimycin phase,” and the difference between the level of oxidized cytochrome c in the presence of stigmatellin and that recorded in the presence of myxothiazol will be referred as “myxothiazol phase.”1 These two phases reveal major differences between the wild type and the A181T mutant.

In A181T under the same experimental conditions (pH 7, Eh 100 mV) the re-reduction of cytochrome c in the absence of any inhibitors is slower but complete (Fig. 4B, black, see Table 2 for corresponding rate of heme b reduction measured in the presence of antimycin). Remarkably, the antimycin phase has significantly lower amplitude than that of wild-type (less cytochrome c gets re-reduced in the presence of antimycin) (Fig. 4B, Table 3). Also the myxothiazol phase is smaller (in the mutant it is approximately one fourth of the total amplitude of flash-oxidized cytochrome c seen in the presence of stigmatellin, while in the wild-type it is approximately one third of the total amplitude) (Fig. 4B, Table 3).

Table 3.

Fraction of cytochrome c re-reduced in chromatophores containing wild-type cytochrome bc1 or the A181T mutant after its oxidation by single flash in the presence of antimycin or myxothiazol (antimycin or myxothiazol phase).

| WT |

A181T |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 6 | pH 7 | pH 9 | pH 6 | pH 7 | pH 9 | |

| Antimycin phase | 0.62 | 0.77 | 1 | 0.46 | 0.58 | 0.78 |

| Myxothiazol phase | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.50 |

At acidic pH (pH 6, Eh 150 mV maintaining the Q pool half-reduced), the antimycin phase in the wild type and the mutant (Fig. 4C, D; Table 3) is smaller comparing to the respective phases recorded at pH 7. The myxothiazol phase remains similar in the wild type, while it slightly diminishes in the mutant (Fig. 4C, D; Table 3), when again compared to the respective phases recorded at pH 7. At alkaline pH (pH 9, Eh -20 mV) the antimycin phase much increases both in the wild type and the mutant, approaching the level of fully re-reduced cytochrome c in the absence of inhibitors (Table 3). The myxothiazol phase in both cases also increases to reach about a half of the total amplitude of flash-oxidized cytochrome c seen in the presence of stigmatellin (Table 3). At this pH the differences between the wild type and the mutant fade out.

With this kinetic screening over pH certain features become apparent. When the mutant is compared with the wild type at given pH, the changes in the post-flash equilibrium distribution of electrons are most prominent when antimycin is present (the antimycin phase is generally smaller in the mutant) but are not seen with the non-inhibited system (cytochrome c is fully re-reduced in both the wild type and the mutant). A similar type of change in the distribution of electrons is also generated by changing pH (the antimycin phase decreases with lowering pH in both the mutant and the wild type).

3.3. Barrier for electron transfer between the FeS cluster and heme c1

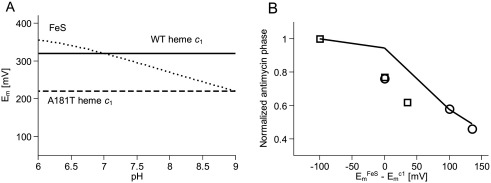

Fig. 5A illustrates a shift in the Em of heme c1 in A181T across pH and the effect of pH on the Em of the FeS cluster. Since the Em of heme c1 in A181T is 100 mV lower than that of wild type (Fig. 3, Table 1), it is reasonable to expect that changes in electron distribution, reminiscent of a barrier for electron transfer, are correlated with a difference in Ems between the FeS cluster and heme c1; the lower the Em of heme c1 will be with respect to the Em of the FeS cluster, the larger the barrier for electron transfer will be and consequently less of cytochrome c will get reduced in the flash experiment. This effect should strongly depend on pH, as the barrier of potential difference strongly depends on pH (in the tested pH range the Em of FeS cluster falls with pH increase while that of heme c1 does not; Fig. 5A and ref. [43]). The about 100 mV barrier present at pH 7 (the Em7 of the FeS cluster is 320 mV) is much diminished at pH 9, where the Em of the FeS cluster drops about 120 mV and approaches that of mutated cytochrome c1 (Em9 = 223 mV; Table 1). On the other hand, at pH 6 the Em of the FeS cluster raises to about 350 mV, which increases the barrier present at pH 7. Indeed, the pH dependence of the amplitude of the antimycin phase appears to track the size of the barrier (the amplitude decreases with decreasing pH as the barrier increases) (Fig. 5B, circles).

Fig. 5.

Difference in midpoint potential between the FeS cluster and heme c1 and its influence on the post-flash distribution of electrons in the c-chain in the presence of antimycin. (A) pH-dependence of Em of the FeS cluster (dotted line) and heme c1 in wild type (solid line) and in A181T mutant (dashed line). Horizontal dashed line for A181T is assumed from the similar values of Em measured at pH 7 and 9 (Table 1). (B) The experimentally determined fraction of cytochrome c re-reduced in the wild type (open squares) and A181T mutant (open circles) in the presence of antimycin (antimycin phase) is plotted vs. difference in Ems between the FeS cluster and heme c1. Solid line represents the changes in the fraction of cytochrome c re-reduced simulated for the conditions when antimycin is present by the model described in Fig. 6D.

With these considerations, a similar tracking becomes evident also for the wild type (Fig. 5B, squares). In this case the barrier of potential difference changes with pH in the same direction, although its absolute value at given pH is smaller comparing to the mutant (Em of heme c1 is higher) (Fig. 5A). Consequently, the amplitude of the antimycin phase also decreases with decreasing pH, although its size at given pH (in particular at pH 6 and 7) is larger than the respective amplitude in the mutant (Fig. 4, Table 3).

The changes in the barrier of potential difference between the FeS cluster and heme c1 are also reflected in the changes in the amplitude of myxothiazol phase. This phase diminishes from about a half of the total amplitude of the oxidized cytochrome c at pH 9 (in both the wild type and the mutant), to about one third in wild type or one fourth in the mutant at pH 7 and 6 (Table 3). Not only this dependency can again be correlated with increase in the barrier of potential difference, but also the smaller myxothiazol phase in the mutant at pH 7 or 6 in comparison to the wild type appears to reflect a larger barrier of potential difference at these two pHs in the mutant.

It thus become clear that the barrier of the difference in midpoint potential between the FeS cluster and heme c1 does influence the post-flash distribution of electrons in the c-chain in the presence of antimycin or myxothiazol. Dropping a midpoint potential of heme c1 by mutation acts only to enhance the effects and trends naturally present in the native system. This, in principle, helps in interpreting the results. However, the electron exchange between the FeS cluster and heme c1 is only one step in the more complex reaction sequence involving two chains of cofactors. Thus understanding of the meaning of the changes in the post-flash distribution of electrons in one chain under the blockage of the outflow of electrons from the second chain (the antimycin case) requires modeling.

3.4. Kinetic model of electron flow in the c-chain

We consider the kinetic model which uses the postulates of the original equilibrium model described in ref. [6]: an adequacy of the equilibrium redox potential values, the amount of oxidized equivalents per single flash, and a strict coupling of reactions at the Qo site. The latter postulate accommodates the Q/QH2 exchange at the Qo site which means that the forward reaction takes place when the QH2, oxidized FeS and oxidized heme bL are all present at the site, while the reverse reaction takes place when the Q, reduced FeS and reduced heme bL are all present at the site. In this model all steps of electron transfer are reversible and independent of each other. In addition, the effect of change in distance between cofactors on the electron transfer coming from the movement of the FeS head domain is simplified to include just the two states that switch between themselves independently of any other event in the enzyme. Because all the experiments were done at Eh equal to the Em of the quinone pool, the concentrations of Q and QH2 are considered equal.

Figs. 5B and 6 show that with these simple assumptions the model generally reproduces the observed trends and changes in the post-flash electron distribution in the wild type and the mutant, with and without inhibitors, at different pHs. This guides us into the following description of electron transfer reactions.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of post-flash electron distribution in wild type and A181T cytochrome bc1. Schemes in A, B compare wild type (WT) with A181T for a given set of conditions. Black and white squares represent reduced and oxidized cofactors, respectively. Incomplete reduction is represented in a grey scale. Dotted squares mark the cofactors of c-chain that are observable in the flash experiments. (A) Single flash generates two oxidizing equivalents per cytochrome bc1 (white squares c) [38] at the time where hemes b are oxidized (white squares bL and bH) and the FeS cluster and heme c1 are reduced (black squares FeS and c1, respectively). (B) Within tens of milliseconds electrons redistribute to reach equilibrium in which the reduction levels of cofactors vary depending on experimental conditions. In the absence of inhibitors, unperturbed electron flow out of the b-chain upon oxidation of two QH2 secures complete re-reduction of all cofactors in the c-chain in both WT and A181T (black squares in no inhibitor panel). In the presence of antimycin, the level of reduced hemes b available for reverse reaction is higher and the equilibrium is reached before the c-chain is fully reduced. In WT, incomplete oxidation of second QH2 (grey squares in antimycin panel) leaves FeS partially oxidized, which leads to redistribution of electrons in the entire c-chain, as observed by flash at the level of cytochromes c (note that intensity of squares in c-chain should be reduced, which for simplicity is not shown). In A181T, incomplete oxidation of second QH2 faces additional barrier of potential difference between FeS and heme c1 which shifts equilibrium toward reduced FeS at the expense of reduced heme c1 (represented as black square FeS and light grey square c1). This increases probability of reverse reaction and decreases probability of forward reaction at the Qo site, and the level of reduced heme bL may decrease (note that in this case the reduction level of heme c1 determines the reduction level of heme bL, as represented by light grey squares c1 and bL). In the presence of myxothiazol (myxothiazol panel), electron from pre-reduced FeS cluster redistributes among the cofactors of the c-chain, but in WT the oxidation of FeS cluster by cytochromes c is more prominent than in A181T (note that for simplicity, for WT a complete electron transfer from FeS cluster to heme c is shown, white square FeS and black squares c). In the presence of stigmatellin (stigmatellin panel) only cytochromes c are in equilibrium thus full extent of flash-oxidized cytochromes c is preserved. Panel (C) shows simulations of the traces for the reduction of the observable experimentally cytochromes c in WT (dashed line) and A181T (solid line) obtained from the model schematically presented in panel (D). The time constants for partial reactions denote k0f/k0b — association/dissociation rate of Q to/from the Qo site, k1f/k1b — same as k0f/k0b but for QH2, k2f/k2b — two-electron oxidation/reduction of QH2/Q in the Qo site, k3f/k3b — rate constants for movement of the FeS head domain to/from cytochrome c1 position, k4f/k4b — rate constants for electron transfer from FeS to heme c1 or reverse reaction, k5f/k5b — rate constant for electron transfer from heme c1 to heme c or reverse reaction. Dotted line in the antimycin panel in C shows the trace simulated for A181T assuming that QH2 oxidation at the Qo site was concerted but irreversible (i.e., k2b = 0 M-1s-1). This illustrates the prediction of how the system would respond if at least one reaction was irreversible (a case not supported experimentally).

The full cytochrome c re-reduction in the absence of any inhibitor consumes electrons from the pre-reduced FeS cluster and then from quinols that are oxidized at the Qo site in a coupled reaction that delivers the second quinol-born electron to the b-chain. A completeness of this reaction is a consequence of the unperturbed outflow of electrons from hemes b to the Qi site and further down to the Q pool. In another words, a completion of two reactions of QH2 oxidation at the Qo site secured by an immediate removal of electrons from hemes b leaves all cofactors in the c-chain (including the FeS cluster) fully saturated with electrons. The reaction is driven to completion even when heme c1 has potential 100 mV lower than Em of FeS in the mutant (Fig. 6, no inhibitor panel). This is consistent with the observations that the Em of heme c1 can be lowered within this range without affecting the overall electron flow through the c-chain [27,44]. In fact, the difference in Ems between heme c1 and the FeS cluster can be as much as 180 mV and the enzyme still muster enough electron transfer through cytochrome bc1 to support its functionality [27].

However, when the outflow of electrons from the b-chain is blocked with antimycin, the b-chain gets saturated with electrons and hemes b remain reduced for significant amount of time. This increases the effective concentration of one of the substrate needed for reverse reaction at the Qo site (reduced heme bL). The presence of reduced heme bL can shift the equilibrium of the Qo site reaction depending on the availability of the other substrates for the reverse reaction (quinone and the reduced FeS cluster). It follows that, at a given Q concentration, a probability of the reverse reaction increases as the effective concentration of reduced FeS cluster at the site increases. This happens, for example, when the barrier for electron transfer from the FeS cluster to heme c1 increases, which in our experiments was achieved either by lowering the Em of heme c1 by mutation or by increasing the Em of the FeS cluster through the pH change. Once the oxidation of the second quinol cannot be completed, the c-chain cannot be fully saturated with electrons and consequently the equilibrium distribution of electrons in the entire c-chain is shifted (Fig. 6, antimycin panel). This means a partial backflow of electrons from cytochrome c reflected as a change between the level of reduced cytochrome c in the absence and the presence of antimycin. The model would thus predict that increasing the barrier for electron transfer from the FeS cluster to heme c1 would result in a decrease of the amplitude of the antimycin phase (Figs. 5B, 6C), which is consistent with the experiment (Figs. 4, 5B, Table 3). With this reasoning we can understand why affecting the equilibrium distribution of electrons in the b-chain in the presence of antimycin affects the distribution of electrons in the c-chain (see details in Fig. 6).

We note that if the reaction at the Qo site was considered irreversible, the model would not predict shifts in the presence of antimycin and cytochrome c reduction would always run to completion (see Fig. 6C, dotted line). Similarly, a complete cytochrome c reduction would occur if the reduction of the FeS cluster at the Qo site would be kinetically separated from its oxidation by cytochrome c (an inherent feature of many gating mechanisms). This clearly is not supported experimentally.

In the presence of myxothiazol, the situation is simplified to only include the post-flash equilibrium distribution of electron that comes from the pre-reduced FeS center. In this case the reduction level of cytochrome c again depends of the height of the barrier for electron transfer from the FeS cluster to heme c1. The model predicts that increasing the barrier decreases the myxothiazol phase (Fig. 6, myxothiazol panel) consistent with the experimental observations (Fig. 4, Table 3).

In conclusion, the variations in the distribution of electrons demonstrated in flash experiments guide us into an appreciation of a mechanism in which a shift in the equilibrium of one reaction influences the equilibrium of all remaining reactions in the cofactor chains. To allow this, all the reactions must be kinetically coupled and reversible on a millisecond timescale [6]. This means that, the FeS cluster, which undergoes a movement during catalysis, must equilibrate with both of its partners on a millisecond timescale independently of its redox state and of the redox state of the partners. This would be consistent with a recent observation about a presence of broad distribution of positions of FeS head domain in native cytochrome bc1 [45]. Mechanistically, this model does not require any physical gating, but at the same time it does not preclude it. This model follows a rather simple description in which the direction of electron flow through both of the chains exclusively depends on the rates of all reversible partial reactions, including the Q/QH2 exchange rate to/from the catalytic sites.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust International Senior Research Fellowship to A.O. We are grateful to Prof. Fevzi Daldal (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA) for a generous gift of the genetic system for cytochrome bc1 in Rhodobacter capsulatus, and to Prof. P. Leslie Dutton (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA) for a generous gift of the optical assembly of the time-resolved spectrophotometer.

Footnotes

In flash experiments, traces recorded in the presence of stigmatellin often show unspecific drift upwards (this drift becomes larger as pH increases), as most clearly seen in Fig. 4A. For each trace, the beginning of the linear part of the curve was taken to calculate the amplitude of antimycin and myxothiazol phase.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.11.003.

Appendix A.

References

- 1.Mitchell P. Protonmotive redox mechanism of the cytochrome b-c1 complex in the respiratory chain: protonmotive ubiquinone cycle. FEBS Lett. 1975;56:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt U., Trumpower B.L. The protonmotive Q cycle in mitochondria and bacteria. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1994;29:165–197. doi: 10.3109/10409239409086800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry E.A., Guergova-Kuras M., Huang L., Crofts A.R. Structure and function of cytochrome bc complexes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:1005–1075. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cape J.L., Bowman M.K., Kramer D.M. Understanding the cytochrome bc complexes by what they don't do. The Q cycle at 30. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crofts A.R. Proton pumping in the bc1 complex: a new gating mechanism that prevents short circuits. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1757:1019–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osyczka A., Moser C.C., Daldal F., Dutton P.L. Reversible redox energy coupling in electron transfer chains. Nature. 2004;427:607–612. doi: 10.1038/nature02242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osyczka A., Moser C.C., Dutton P.L. Fixing the Q cycle. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rich P.R. The quinone chemistry of bc complexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1658:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snyder C.H., Gutierrez-Cirlos E.B., Trumpower B.L. Evidence for a concerted mechanism of ubiquinol oxidation by the cytochrome bc1 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:13535–13541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooley J.W., Lee D.-W., Daldal F. Across membrane communication between the Qo and Qi active sites of cytochrome bc1. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1888–1899. doi: 10.1021/bi802216h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Covian R., Trumpower B.L. Regulatory interactions in the dimeric cytochrome bc1 complex: the advantages of being a twin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1777:1079–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esser L., Gong X., Yang S., Yu L., Yu C.A., Xia D. Surface-modulated motion switch: capture and release of iron-sulfur protein in the cytochrome bc1 complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:13045–13050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601149103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulkidjanian A.Y. Proton translocation by the cytochrome bc1 complexes of phototrophic bacteria: introducing the activated Q-cycle. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2007;6:19–34. doi: 10.1039/b517522d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crofts A.R., Holland J.T., Victoria D., Kolling D.R.J., Dikanov S.A., Gilbreth R., Lhee S., Kuras R., Guergova Kuras M. The Q-cycle reviewed: how well does a monomeric mechanism of the bc1 complex account for the function of a dimeric complex? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008:1777. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu C.A., Cen X., Ma H.-W., Yin Y., Yu L., Esser L., Xia D. Domain conformational switch of the iron-sulfur protein in cytochrome bc1 complex is induced by the electron transfer from cytochrome bL to bH. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1777:1038–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darrouzet E., Moser C.C., Dutton P.L., Daldal F. Large scale domain movement in cytochrome bc1: a new device for electron transfer in proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:445–451. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01897-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutierrez-Cirlos E.B., Trumpower B.L. Inhibitory analogs of ubiquinol act anti-cooperatively on the yeast cytochrome bc1 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:1195–1202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooley J.W., Ohnishi T., Daldal F. Binding dynamics at the quinone reduction (Qi) site influence the equilibrium interactions of the iron–sulfur protein and hydroquinone oxidation (Qo) site of the cytochrome bc1 complex. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10520–10532. doi: 10.1021/bi050571+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muller F., Crofts A.R., Kramer D.M. Multiple Q-cycle bypass reactions at the Qo site of the cytochrome bc1 complex. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7866–7874. doi: 10.1021/bi025581e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forquer I., Covian R., Bowman M.K., Trumpower B.L., Kramer D.M. Similar transition states mediate thye Q-cycle and superoxide production by the cytochrome bc1 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:38459–38465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605119200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drose S., Brandt U. The mechanism of mitochondrial superoxide production by the cytochrome bc1 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:21649–21654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borek A., Sarewicz M., Osyczka A. Movement of the iron-sulfur head domain of cytochrome bc1 transiently opens the catalytic Qo site for reaction with oxygen. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12365–12370. doi: 10.1021/bi801207f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berry E.A., Lee D.-W., Huang L.-S., Daldal F. Structural and mutational studies of the cytochrome bc1 complex. In: Hunter N., Daldal F., Thurnauer M.C., Beatty J.T., editors. The purple phototrophic bacteria. Springer; The Netherlands: 2009. pp. 425–450. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray K.A., Davidson E., Daldal F. Mutagenesis of methionine-183 drastically affects the physicochemical properties of cytochrome c1 of the bc1 complex of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Biochemistry. 1992;31:11864–11873. doi: 10.1021/bi00162a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darrouzet E., Mandaci S., Li J., Qin H., Knaff D.B., Daldal F. Substitution of the sixth axial ligand of Rhodobacter capsulatus cytochrome c1 heme yields novel cytochrome c1 variants with unusual properties. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7908–7917. doi: 10.1021/bi990211k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osyczka A., Dutton P.L., Moser C.C., Darrouzet E., Daldal F. Controlling the functionality of cytochrome c1 redox potentials in the Rhodobacter capsulatus cytochrome bc1 complex through disulfide anchoring of a loop and a β-branched amino acid near the heme-ligating methionine. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14547–14556. doi: 10.1021/bi011630w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang H., Osyczka A., Moser C.C., Dutton P.L. Resilience of Rhodobacter sphaeroides cytochrome bc1 to heme c1 ligation changes. Biochemistry. 2006;45:14247–14255. doi: 10.1021/bi061345i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berry E.A., Huang L.-S., Saechao L.K., Pon N.G., Valkova-Valchanova M.B., Daldal F. X-ray structure of Rhodobacter capsulatus cytochrome bc1: comparison with its mitochondrial and chloroplast counterparts. Photosynth. Res. 2004;81:251–275. doi: 10.1023/B:PRES.0000036888.18223.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elberry M., Yu L., Yu C.A. The disulfide bridge in the head domain of Rhodobacter sphaeroides cytochrome c1 is needed to maintain its structural integrity. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4991–4997. doi: 10.1021/bi0522246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daldal F., Davidson E., Cheng S. Isolation of the structural genes for the Rieske Fe-S protein, cytochrome b and cytochrome c1 all components of the ubiquinol: cytochrome c2 oxidoreductase complex of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J. Mol. Biol. 1987;195:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atta-Asafo-Adjei E., Daldal F. Size of the amino acid side chain at position 158 of cytochrome b is critical for an active cytochrome bc1 complex and for photosynthetic growth of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991;88:492–496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.2.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valkova-Valchanova M.B., Saribas A.S., Gibney B.R., Dutton P.L., Daldal F. Isolation and characterization of a two-subunit cytochrome b-c1 subcomplex from Rhodobacter capsulatus and reconstitution of its ubihydroquinone oxidation (Qo) site with purified Fe-S protein subunit. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16242–16251. doi: 10.1021/bi981651z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dutton P.L. Redox potentiometry: determination of midpoint potentials of oxidation-reduction components of biological electron-transfer systems. Methods Enzymol. 1978;54:411–435. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)54026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osyczka A., Zhang H., Mathe C., Rich P.R., Moser C.C., Dutton P.L. Role of the PEWY glutamate in hydroquinone-quinone oxidation-reduction catalysis in the Qo site of cytochrome bc1. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10492–10503. doi: 10.1021/bi060013a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robertson D.E., Davidson E., Prince R.C., van der Berg W.H., Marrs B.L., Dutton P.L. Discrete catalytic sites for quinone in the ubiquinol-cytochrome c2 oxidoreductase of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:584–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharp R.E., Palmitessa A., Gibney B.R., Daldal F., Moser C.C., Dutton P.L. Correlation between cytochrome bc1 structure and function. Spectroscopic and kinetic observations on Qo site occupancy and dynamics. In: Peschek G.A., Loffelhard W., Schmetterer G., editors. The Phototrophic Prokaryotes. Kluwer Academic, Plenum Publishers; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 37.C.P. Fall, E.S. Marland, J.M. Wagner, J.J. Tyson, Computational Cell Biology, Springer-Verlag, New York, 2002.

- 38.Ding H., Moser C.C., Robertson D.E., Tokito M.K., Daldal F., Dutton P.L. Ubiquinone pair in the Qo site central to the primary energy conversion reactions of cytochrome bc1 complex. Biochemistry. 1995;34:15979–15996. doi: 10.1021/bi00049a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moser C.C., Keske J.M., Warncke K., Farid R.M., Dutton P.L. Nature of biological electron transfer. Nature. 1992;355:796–802. doi: 10.1038/355796a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Page C., Moser C., Dutton L.P. Mechanism for electron transfer within and between proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2003;7:551–556. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ransac S., Parisey N., Mazat J.-P. The lonelines of the electrons in the bc1 complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1777:1053–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Darrouzet E., Valkova-Valchanova M.B., Moser C.C., Dutton P.L., Daldal F. Uncovering the [2Fe2S] domain movement in cytochrome bc1 and its implications for energy conversion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:4567–4572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang H., Chobot S.E., Osyczka A., Wraight C.A., Dutton P.L., Moser C.C. Quinone and non-quinone redox couples in complex III. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2008;40:493–499. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9174-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li J., Osyczka A., Conover R.C., Johnson M.K., Qin H., Daldal F., Knaff D.B. Role of acidic and aromatic amino acids in Rhodobacter capsulatus cytochrome c1. A site-directed mutagenesis study. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8818–8830. doi: 10.1021/bi020693r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarewicz M., Dutka M., Froncisz W., Osyczka A. Magnetic interactions sense changes in distance between heme bL and iron-sulfur cluster in cytochrome bc1. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5708–5720. doi: 10.1021/bi900511b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.