Abstract

The mechanisms governing the population of tissues by mast cells are not fully understood, but several studies using human mast cells have suggested that expression of the chemokine receptor CCR3 and migration to its ligands may be important. In CCR3-deficient mice, a change in mast cell tissue distribution in the airways following allergen challenge was reported compared with wild-type mice. In addition, there is evidence that CCR3 is important in mast cell maturation in mouse. In this study, bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMCs) were cultured and CCR3 expression and the migratory response to CCR3 ligands were characterized. In addition, BMMCs were cultured from wild-type and CCR3-deficient mice and their phenotype and migratory responses were compared. CCR3 messenger RNA was detectable in BMMCs, but this was not significantly increased after activation by immunoglobulin E (IgE). CCR3 protein was not detected on BMMCs during maturation and expression could not be enhanced after IgE activation. Resting and IgE-activated immature and mature BMMCs did not migrate in response to the CCR3 ligands eotaxin-1 and eotaxin-2. Comparing wild-type and CCR3-deficient BMMCs, there were no differences in mast cell phenotype or ability to migrate to the mast cell chemoattractants leukotriene B4 and stem cell factor. The results of this study show that CCR3 may not mediate mast cell migration in mouse BMMCs in vitro. These observations need to be considered in relation to the findings of CCR3 deficiency on mast cells in vivo.

Keywords: CCR3, chemokine, chemotaxis, mast cell

Introduction

Mast cells are regulators of allergic inflammation and have roles in host defence against pathogens, immunological tolerance, autoimmune diseases, atherosclerosis and cancer.1 After recruitment of circulating committed mast cell progenitors, mast cells undergo differentiation and maturation in the tissues. An increase in mast cell numbers is observed in conditions such as allergic rhinitis and asthma, where mast cells contribute to the pathophysiology.2–5 The mechanisms governing the population of tissues by mast cells are not fully understood so elucidation and identification of factors and mechanisms regulating this process could provide targets for therapeutic intervention.

The chemokine receptor CCR3 is expressed on several cell types including eosinophils,6–8 basophils,9 T helper type 2 cells,10 airway smooth muscle cells11 and mast cells.12–17 Ochi et al. observed that human mast cell progenitors expressed four chemokine receptors, but only CCR3 remained upon maturation.14 Several other studies have confirmed CCR3 expression on mast cells and demonstrated that mast cells migrate towards CCR3-binding chemokines.12,15–18 The majority of these studies have been conducted using human mast cells. Further understanding of the contribution of CCR3 to the population of tissues by mast cells has been determined using in vivo mouse models.

CCR3-deficient mice (CCR3−/−) have been generated19 and mast cell localization was observed in different disease situations.19–23 Humbles et al. reported an altered mast cell distribution in the airways of CCR3−/− mice in a model of allergic airways inflammation19 but other studies have shown no effect using different disease models.20,21 There is also evidence to suggest that the CCR3 ligand eotaxin-1 (CCL11) may be important in mast cell maturation.24–27 Apart from investigation of the effect of CCR3 deficiency in disease models, the expression and function of CCR3 on mouse mast cells in vitro has not been previously studied in depth.17,27

The aim of this study was to characterize CCR3 expression and function in mouse bone-marrow-derived mast cells (BMMC) to further elucidate the role of CCR3 on mast cells. Immature and mature mast cells were cultured and analysed for CCR3 expression under resting and activated conditions at the messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein level. Also, immature and mature wild-type (WT) and CCR3-deficient mast cells were compared phenotypically and functionally in chemotaxis assays. The results of this study may be critical to understanding the similarities and differences that may be present between mouse and human mast cells.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Tissue culture reagents were all purchased from Invitrogen (Paisley, UK). Mouse chemokines and cytokines were from Peprotech (London, UK) and lipid mediators were from Cayman Chemicals (ISD Ltd, Boldon, UK). All antibodies for flow cytometry were from BD Biosciences (Oxford, UK) except mouse anti-CCR3 and isotype control, which were from R&D Systems (Abingdon, UK). TaqMan universal PCR mastermix, CCR3, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and 18S specific primers were from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA).

Mice

Female BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan. Mice deficient in CCR3 and their WT littermate controls were a kind gift from Dr C. Gerard, Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School (Cambridge, MA). CCR3−/− mice were generated on a BALB/c background.19 Animals were housed at the Imperial College London animal facility and were used at 6–8 weeks of age. Food and water were supplied ad libitum. UK Home Office guidelines for animal welfare based on the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986 were strictly observed.

BMMC culture

Mouse BMMC were cultured for up to 10 weeks at 37° in 5% CO2 from BALB/c femoral bone marrow cells at 5 ×105/ml in RPMI-1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 μm 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 5 ng/ml murine interleukin-3 (IL-3; Peprotech, London, UK) as previously described.28 Aliquots of BMMC were removed at weekly or fortnightly intervals throughout culture for characterization by flow cytometry.

Cell surface immunofluorescence and flow cytometry

Independent BMMC cultures were characterized by repeated sampling at weekly and fortnightly intervals during the 10 weeks of culture. Cells were double-stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD117 (c-kit, 2B8) (to identify the mast cell population) and one of the following fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated (-FITC) rat anti-mouse cell surface markers: CD34 (RAM34), CD13 (R3-242), T1/ST2 (DJ8), α4 (R1-2), β7 (M293), immunoglobulin E (IgE)-DNP (SPE-7) [followed by IgE-FITC (R35-72)] or their isotype controls IgG2a (R35-95), IgG2b (R35-38), IgG1 (R3-34) for 20–30 min as above. For FcεR1 staining, after Fc blocking, BMMC were incubated with anti-DNP IgE for 20 min followed by FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgE. For intracellular antigens, after extracellular c-kit staining, BMMCs were incubated with Cell Fix (BD Biosciences) at 1 : 10 dilution in water on ice for 15 min. The cells were then permeabilized with 0·1% saponin in staining buffer for 5 min before incubation with the antibodies for intracellular staining. Stained cells were analysed on a flow cytometer (model FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences).

Mouse BMMC chemotaxis

Twenty microlitres of BMMC were added to the top of 96-well chemotaxis plates (5-μm pore size; Neuroprobe, Gaithersburg, MD) at 2 × 106 cells/ml and agonist or buffer was added to the lower wells; after a 3 hr incubation at 37°, migrated cells were stained with c-kit and Gr-1 for flow cytometry, as described previously.28 Where indicated, the upper sides of the chemotaxis filters were coated with 1 μg/ml fibronectin in chemotaxis buffer and allowed to air dry before assay. Assays were performed in duplicate and results for c-kit+ cells are expressed as absolute number of cells migrating and results for Gr-1 cells are expressed as chemotactic index (number of cells migrating to chemokine/number of cells migrating to buffer).

Real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis

The c-kit+ BMMC were purified by positive selection through magnetic columns (magnetic antibody cell sorting; Miltenyi Biotec, Bisley, UK) at weekly or fortnightly intervals. Purity of > 95% c-kit+ cells was confirmed by flow cytometry. Total RNA was extracted from purified BMMC and complementary DNA was synthesized from 450 ng total RNA as previously described.29 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in triplicate using the sequence detection system (models ABI Prism 7500 and 7700) with TaqMan universal PCR mastermix and CCR3, GAPDH and 18S specific primers. Relative CCR3 receptor mRNA expression was quantified using the comparative threshold (CT) for detection method (http://appliedbiosystems.com). CT values for CCR3 were standardized against housekeeping genes GAPDH and 18s to give relative expression values.

Mast cell activation

Mature (10 week) BMMC (5 × 106 cells/ml) were activated with 10 μg/ml anti-DNP IgE for 1 hr at 37° followed by human serum albumin-dinitrophenol (HSA-DNP) at 40 ng/ml for 1 hr as previously described.28 Control groups of BMMC were left unactivated or were incubated with anti-DNP IgE or HSA-DNP alone. After activation the groups of cells were split and total RNA was extracted and complementary DNA was synthesized from 300 ng total RNA for real-time PCR analysis. The supernatants and pellets from the remaining BMMC were frozen for β-hexosaminidase release analysis to confirm that the IgE activation had induced mast cell degranulation.30 Activation routinely induced 20–30%β-hexosaminidase release.

Statistics

Datasets containing groups of three or more were analysed using a Kruskal–Wallis test with pairs of groups compared by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. For datasets containing groups of two, the Mann–Whitney test was used. To compare groups at multiple concentrations, two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-test was used. A value of P < 0·05 was considered significant. Graph generation and statistical analysis were performed using prism software (version 4.00; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

CCR3 mRNA expression on BMMC

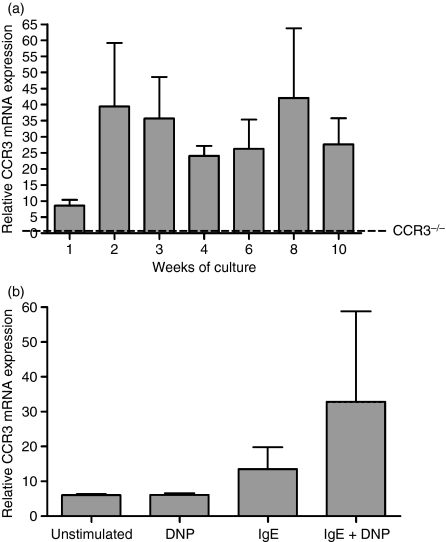

CCR3 mRNA in IL-3-cultured c-kit+ BMMC was measured by repeated sampling of three independent BMMC cultures at weekly or fortnightly intervals up to 10 weeks (Fig. 1a) by real-time PCR. CCR3 mRNA was low on c-kit+ BMMC after 1 week in culture. By week 2, CCR3 mRNA had apparently increased fourfold and was maintained to week 10 of culture but the differences were not statistically significant (n = 3 from independent BMMC cultures, P = 0·3105; Fig. 1a). At 4 weeks of culture, relative CCR3 mRNA expression was 24·05 ± 3·101 compared with 1·38 ± 0·480 (n = 1) in 4-week BMMC derived from CCR3-deficient mice (Fig. 1a, dashed line).

Figure 1.

CCR3 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression on mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMC). Relative CCR3 mRNA expression on BMMC from 1–10 weeks in culture with interleukin-3 (IL-3) measured by real-time polymerase chain reaction, dashed line (––) indicates level of relative CCR3 mRNA expression on 4-week BMMC from CCR3−/− mice (a). Relative CCR3 mRNA expression on immunoglobuoin E (IgE)-activated 10-week mature c-kit+ cells (b). Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3) using RNA from three independent cultures. Statistical significance was determined using the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison post-test. DNP, dinitrophenol.

To determine whether CCR3 mRNA could be increased upon cell activation, 10-week mature BMMC were activated by antigen cross-linking of FcεR1 receptor. Following activation, the relative amount of CCR3 mRNA was measured by real-time PCR and compared with that in unactivated cells or cells that did not undergo FcεR1 cross-linking [cells exposed to IgE (13·51 ± 6·284) or the DNP antigen alone (6·074 ± 0·4946)]. Figure 1(b) shows that FcεR1 cross-linking induced an apparent increase in CCR3 mRNA (32·85 ± 25·97) compared with unactivated cells (6·046 ± 0·2935) but this was not statistically significant (n = 3 from independent BMMC cultures, P = 0·8137).

Expression of CCR3 protein on BMMC

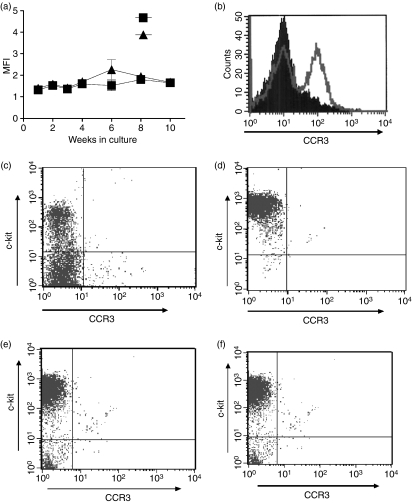

Mouse BMMC from independent cultures were examined for CCR3 expression by flow cytometry by repeated sampling at weekly or fortnightly intervals during 10 weeks of culture. Surface expression of CCR3 was not detected on BMMC at any stage during the 10 weeks of culture (Fig. 2a). In addition to culture with IL-3, BMMC were cultured with IL-3 + stem cell factor (SCF) and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), IL-3, IL-9 and SCF. CCR3 expression was not detected on these BMMC at any stage during the 10 weeks of culture (data not shown).

Figure 2.

CCR3 protein expression on mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMC). Surface expression of CCR3 or isotype control on BMMC from 1–10 weeks in culture with interleukin-3 (IL-3). Data are n = 3 using cells from three independent BMMC cultures (a). Surface expression of CCR3 on mouse allergen-challenged lung cells. Closed histogram indicates isotype control and open histogram CCR3 staining (b). Intracellular expression of CCR3 on 2-week (c) and 10-week (d) BMMC. Extracellular expression of CCR3 on resting (e) and immunoglobulin E (IgE)-activated (f) 10-week mature BMMC. Representative dot plots show CCR3 expression. The upper left quadrant of the dot plots indicates the location of the c-kit phycoerythrin+, fluorescein isothiocyanate isotype control population.

The CCR3 antibody used was able to detect CCR3 in homogenized lung tissue from ovalbumin-sensitized and challenged mice (from Dr Darren Campbell, Imperial College London, UK) which was used as a positive control (Fig. 2b). The lungs of these allergic mice contain a large number of CCR3+ eosinophils that may be easily detected by flow cytometry31 but very few mast cells.32 Since CCR3 was not detected extracellularly (Fig. 2a), BMMC were permeabilized before CCR3 staining to determine whether the receptor is being stored intracellularly. CCR3 expression was not detected intracellularly in 2-week immature (Fig. 2c) or 10-week mature BMMC (Fig. 2d).

To determine whether mast cell activation induced surface CCR3 expression, mouse 10-week BMMC were activated by FcεR1 cross-linking and stained for CCR3 by flow cytometry. Unactivated BMMC did not express CCR3 extracellularly (Fig. 2e) and expression was not induced after activation for 1 hr (Fig. 2f). In addition, CCR3 expression was not detected after antigen incubation for 3, 6 and 18 hr (data not shown).

Migration of mouse BMMC to CCR3 ligands

As shown above, BMMC had detectable CCR3 mRNA but no detectable CCR3 protein. Surface CCR3 expression may have been too low to be detected using the available antibody, therefore we tested CCR3 functional activity using chemotaxis assays. Mouse eotaxin-1 and eotaxin-2 (CCL11 and CCL24 respectively) were unable to induce significant migration of 2-week immature (Fig. 3a) and 10-week mature BMMC (Fig. 3b) compared with buffer alone. In contrast, all cells migrated to the c-kit ligand, SCF a previously described mast cell chemoattractant33,34 (Fig. 3a,b). Two-week BMMC migrated significantly to SCF at 1 nm (109·4 ± 63·86 cells) compared with buffer (2·1 ± 0·48 cells; P = 0·0385). Ten-week BMMC migrated significantly at 0·1 nm (66. 9 ± 35·19 cells) and 1 nm (76·3 ± 23·53) compared with buffer (1·33 ± 1·33; P = 0·0045) This demonstrates that the cells were able to migrate under these experimental conditions, but they specifically did not migrate to the CCR3 ligands tested. To confirm that the mouse chemokines were bioactive, migration of 2-week c-kit− Gr-1+ bone marrow cells was assessed within the same chemotaxis assay. Gr-1 is a myeloid differentiation antigen (Ly-6G and Ly-6C) which is a marker for granulocytes (neutrophils and eosinophils) and monocytes. Eotaxin-1 and eotaxin-2 induced migration of the Gr-1+ bone marrow cells with a maximum chemotactic index of 5·13 ± 2·45 at 0·1 nm for eotaxin-1 and 11·936 ± 8·31 at 10 nm for eotaxin-1 and eotaxin-2 (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Immature and mature bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMC) migration to eotaxin-1 (CCL11) or eotaxin-2 (CCL24). Two-week (a) and 10-week (b) BMMC were assayed for migration towards eotaxin-1 (▪) and eotaxin-2 (▴ 10 pm to 100 nm) and stem cell factor (SCF; +, 0·1–10 nm). After 3 hr incubation, migrated cells were recovered and double stained with anti-c-kit-phycoerythrin and anti-GR-1-fluorescein isothiocyanate and the c-kit+ BMMC were counted by flow cytometry. Two-week Gr-1+ cells migrated towards eotaxin-1 (▪) and eotaxin-2 (▴), 0·1 nm to 100 nm). Data are expressed as chemotactic index (number of migrated Gr-1+ cells/number of cells migrated to buffer; c) Fibronectin coating of chemotaxis membranes did not increase 2-week BMMC migration to eotaxin-1 (d) or SCF (e). FcεR1 cross-linking of BMMC did not induce migration of 2-week (f) or 10-week (g) BMMC to eotaxin-1. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3 to n = 6) from independent BMMC cultures. *Indicates significant migration (P < 0·05) compared with buffer, **Indicates significant migration (P < 0·01) compared with buffer. Statistical significance of chemokine-induced migration compared with buffer alone was determined using Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunns post-test. Concentration response curves were compared using two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post-test.

In addition, migration of BMMC cultured with IL-3 + SCF was determined. Neither 2-week immature nor 10-week mature BMMC migrated to eotaxin-1 or eotaxin-2 but the cells migrated to SCF (data not shown). To determine the effect of fibronectin-coated chemotaxis filters, BMMC migration to chemoattractants was compared in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml fibronectin. Fibronectin coating had little effect on the migration of BMMC; 0·1 and 1 nm eotaxin-1 induced minimal migration of BMMC through fibronectin-coated filters, which was not significantly increased above the response through uncoated filters (P = 0·24529; Fig. 3c). Similarly, over the concentrations tested, there was no significant difference in SCF-induced migration of immature BMMC through fibronectin-coated filters compared with uncoated filters (P = 0·9775; Fig. 3d).

A small increase in CCR3 mRNA expression was observed after activation via FcεR1 cross-linking, so activated BMMC were used in chemotaxis assays to eotaxin-1. Eotaxin-1 was unable to induce migration of activated or unactivated 2-week immature (Fig. 3e) or 10-week mature BMMC (Fig. 3f).

Eotaxin-1 has previously been shown to synergize with SCF during mast cell progenitor differentiation.25,26 We therefore assessed whether eotaxin-1 could synergize with SCF in mast cell chemotaxis. The addition of eotaxin-1 to 0·1–10 nm SCF did not increase migration [for example 1 nm SCF alone (89 ± 22 cells), compared with SCF + eotaxin-1, 0·1 nm (98·75 ± 47·25 cells), 1 nm (128·3 ± 99·75 cells) and 10 nm (119·5 ± 75·50) with n = 2 from two independent BMMC cultures].

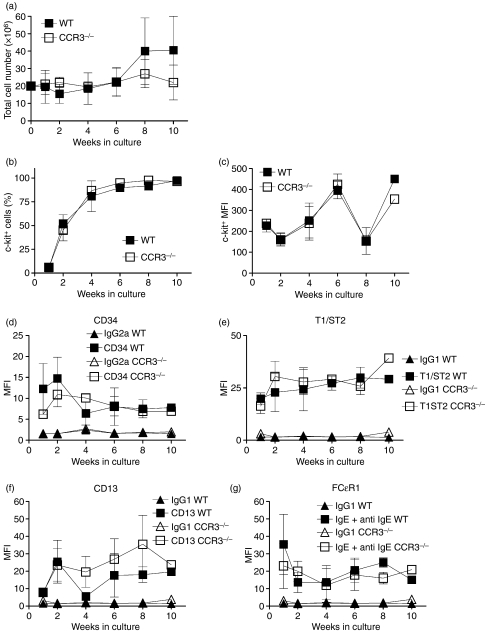

Phenotypic characterization of WT and CCR3-deficient BMMC

To determine whether the absence of CCR3 has any effect on mast cell growth, differentiation and phenotype, BMMC were differentiated from WT and CCR3−/− mice. Bone marrow cells were cultured in IL-3 for up to 10 weeks and expression of mast cell markers was assessed by flow cytometry. There was no difference between the number of total cells from WT and CCR3−/− over 10 weeks of culture (Fig. 4a). After 2 weeks in culture, WT BMMC were 51 ± 10% c-kit+ compared with 45 ± 11% c-kit+ with CCR3−/− BMMCs. Both cell types were > 90% c-kit+ by week 6 of culture (Fig. 4b). The mean fluorescent intensity of c-kit expression fluctuated over the 10 weeks in both cell types but there was no difference between WT and CCR3−/− (Fig. 4c), showing that c-kit expression (an indication of the number of c-kit receptors on the cell surface) does not differ between WT and CCR3−/− BMMC.

Figure 4.

Growth and mature mast cell marker expression on CCR3−/− and wild-type bone marrow-derived mast cells (WT BMMC). WT (▪) and CCR3−/− (□) total cell number in culture over 10 weeks (a). Percentage of c-kit+ WT (▪) and CCR3−/− (□) cells over 10 weeks in culture (b). Expression of mast cell markers c-kit (c), CD34 (d), T1/ST2 (e), CD13 (f) and FcεR1 (g) were measured on WT (▪) and CCR3−/− (□) BMMC over 10 weeks in culture. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3) from independent BMMC cultures.

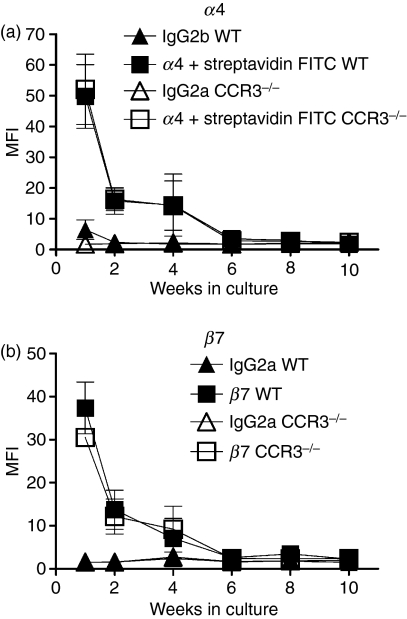

The WT and CCR3−/− BMMC were characterized for expression of various mature mast cell markers. The WT and CCR3−/− BMMC both expressed CD34 (Fig. 4d), T1/ST2 (Fig. 4e), CD13 (Fig. 4f) and FcεR1 (Fig. 4g) but there was no difference between these cultures over 10 weeks of culture. Both WT and CCR3−/− BMMC expressed the progenitor mast cell markers α4 (Fig. 5a) and β7 (Fig. 5b)35,36 highly after 1 week of culture. Expression rapidly decreased over subsequent weeks with no α4 or β7 detected on BMMC by the sixth week of culture (Fig. 5a,b); however, there was no difference between WT and CCR3−/− BMMC during the 10 weeks of culture.

Figure 5.

Progenitor mast cell marker expression on CCR3−/− and wild-type bone marrow-derived mast cells (WT BMMC). α4 integrin (a) and β7 (b) integrin expression on WT (▪) and CCR3−/− (□) BMMC over 10 weeks in culture. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3) from independent BMMC cultures.

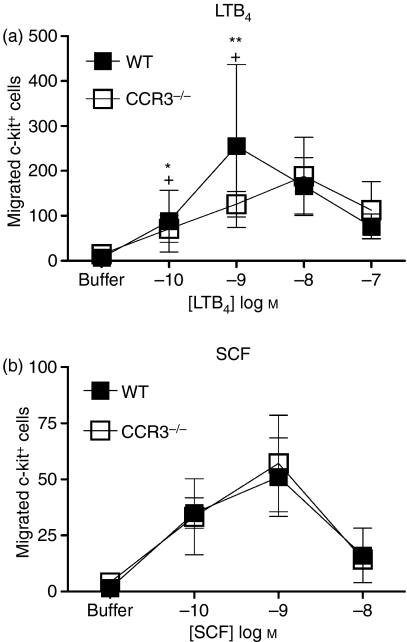

Migration of BMMC from WT and CCR3−/− mice

In the current study, BMMC did not migrate to the CCR3 ligands eotaxin-1 and eotaxin-2 (CCL11 and CCL24, respectively). To determine whether the absence of the CCR3 affects the migratory response to other chemoattractants, WT and CCR3−/− BMMC were compared in chemotaxis assays to leukotriene B4 (LTB4) and SCF which have been previously shown to induce migration of 2-week immature BMMC.28,33 LTB4 induced migration of WT and CCR3−/− BMMCs (Fig. 6a) with significant migration at 1 nm LTB4 (255·3 ± 181·4 cells compared with 6·75 ± 3·119 cells to buffer; P = 0·0213 and 125·9 ± 28·16 compared with 14·25 ± 10·21 cells to buffer; P = 0·0489, respectively). There was no difference in the magnitude of LTB4-induced migration between WT and CCR3−/− BMMCs (P = 0·736). The WT and CCR3−/− BMMC both appeared to migrate to SCF with maximum migration induced by 1 nm, but this did not reach statistical significance (51 ± 17·45 cells compared with 1·5 ± 1 cells to buffer; P = 0·1055 and 57·13 ± 21·48 compared with 4·167 ± 2·242 cells to buffer; P = 0·0788 respectively; Fig. 6b). There was also no significant difference in the chemotactic responses to SCF between WT and CCR3−/− BMMCs (P = 0·8981).

Figure 6.

Migration of CCR3−/− and wild-type bone marrow-derived mast cells (WT BMMC) to the mast cell chemoattractants leukotriene B4 (LTB4) or stem cell factor (SCF). Chemotaxis assays of 2 week WT (▪) and CCR3−/− (□) BMMC were set up to LTB4 (a) and SCF (b). After 3 hr incubation, migrated cells were recovered and double stained with anti-c-kit-phycoerythrin and anti-GR-1-fluorescein isothiocyanate and the c-kit+ BMMCs were counted by flow cytometry. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3) from independent BMMC cultures. *Indicates significant migration (P < 0·05), **Indicates significant migration (P < 0·01) compared with buffer for WT data, + indicates significant migration compared with buffer (P < 0·05) for knockout data. Statistical significance of chemokine-induced migration compared with buffer alone was determined using Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunns post-test. Concentration response curves were compared using two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post-test.

Discussion

The mechanisms governing the population of tissues by mast cells are still not fully understood. Studies into mast cell trafficking have proposed an important role for CCR3 although some of the data are conflicting and the area remains unclear with variations between different sources of mast cells.12,15–17,19 In the current study, mouse BMMC expressed CCR3 mRNA but protein was not detected and the cells did not migrate to CCR3 ligands. In addition, there were no phenotypic differences between BMMC derived from WT and CCR3-deficient mice.

In agreement with a previous report,17 BMMC expressed CCR3 mRNA during the 10 weeks of culture (Fig. 1a). Increased CCR3 surface and mRNA expression was observed after FcεR1 cross-linking of human and mouse cultured mast cells, respectively; however, in this study, CCR3 mRNA expression did not increase significantly after IgE activation (Fig. 1b). In contrast to studies using human cord blood-derived mast cells,14 where immature and mature cord blood-derived mast cell expressed CCR3, BMMC did not express CCR3 extracellularly or intracellularly during the 10 weeks of culture (Fig. 2a,c,d). CCR3 protein expression may have been too low to be detected using the available antibody. CCR3 protein expression has not previously been reported on mouse immature or mature BMMC; however, a recent study showed mature mouse conjunctival mast cells expressed CCR3 protein. This may reflect differences in tissue specificity or the influence of local inflammatory conditions.27

The importance of CCR3 expression on mast cells has been attributed to its role in migration. Studies using human mast cells have described migration to CCR3 ligands.12,13 In the current study, immature and mature BMMC did not migrate towards the CCR3 ligands eotaxin-1, eotaxin-2 under a variety of conditions (Fig. 3). This is in agreement with a previous report showing that local administration of eotaxin-1 in vivo was unable to induce mast cell recruitment to the conjunctiva of mice.27 However, BMMC have been previously reported to migrate to eotaxin-1 after activation using a system where 8-μm pore-size chemotaxis filters were coated in fibronectin.17 This differs from our system where a 5-μm pore-size was used, BMMC were unactivated and filters were uncoated. When filters were coated with fibronectin (Fig. 3b), or BMMC were activated (Fig. 3e,f) chemotaxis to eotaxin-1 was still not observed. Furthermore, the BMMC in the previous report17 were derived from a different strain of mouse (CBA/J compared with BALB/c in the current study). The differences in the assay conditions could explain these contrasting results.

Eotaxin-1 acts synergistically with SCF to accelerate the differentiation of embryonic mast cell progenitors in mice25,26 and to enhance myeloid progenitor production in the bone marrow during lung inflammation in mice.24 When compared, BMMC from WT and CCR3−/− mice were indistinguishable in terms of c-kit expression, rate of growth and mast cell marker expression (Figs 4,5). These results suggest that CCR3 does not have a major effect on mast cell development and is more likely to function on mature mast cells. The absence of CCR3 did not impair migration of BMMC to other chemoattractants as there was no difference in the LTB4-induced and SCF-induced migration of BMMC compared with WT BMMC (Fig 6).

Mast cell CCR3 receptor expression and the role of CCR3 in mast cell trafficking varies between mast cells from different tissues.12,15 In human mast cells CCR3 and its ligand eotaxin-1 are increased in the bronchial mucosa of asthmatics, which correlated with increases in airway hyperresponsiveness.37 In a mouse model of allergic airways inflammation, CCR3−/− mice exhibited enhanced airway hyperresponsiveness, which correlated with increased mast cells in the trachea.19 Conversely, in a model where mice were epicutaneously sensitized and challenged in the airways no difference in airway hyperresponsiveness or tracheal mast cells between WT and CCR3−/− mice was observed.20 Intestinal mast cell number between CCR3−/− and WT mice in response to helminth infection was unaltered21 and there was no significant difference in basal mast cell progenitor numbers in the intestine or in the allergen-challenged lung between WT and CCR3−/− mice.22,23 These results suggest that the role of CCR3 in mast cell function varies between mouse and human and in different physiological settings. CCR3 may be important for the relocation of mature mast cells within tissues such as the trachea, where they may contribute to airway hyperresponsiveness, rather than recruitment of progenitors. A recent study demonstrated that eotaxin-1 was required for a costimulatory signal in FcεR1-mediated activation of mouse mast cells27 suggesting an alternative role for eotaxin/CCR3 on mouse mast cells.

The results of the current study suggest CCR3 and its ligands are not involved in mouse mast cell migration or development in vitro. This is in contrast to human mast cells where CCR3 expression and function has been demonstrated in vitro. Our results also emphasize the heterogeneity of mast cells from different tissues, inflammatory settings and, importantly, species.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr Craig Gerard at Harvard Medical School for the kind gift of CCR3-deficient mice. Also, Miss Gill Martin and Dr Darren Campbell at Imperial College for assistance in BMMC preparation and donation of mouse lung tissue, respectively. This work was funded by a PhD studentship from Novartis and Asthma UK.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- BMMC

bone marrow-derived mast cell

- CCR

CC chemokine receptor

- FcεR1

high affinity immunoglobulin E receptor

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- HSA-DNP

human serum albumin-dinitrophenol

- IL

interleukin

- LTB4

leukotriene B4

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- OVA

ovalbumin

- PE

phycoerythrin

- SCF

stem cell factor

- TGF

transforming growth factor

Disclosures

Authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sayed BA, Christy A, Quirion MR, Brown MA. The master switch: the role of mast cells in autoimmunity and tolerance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:705–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fokkens WJ, Godthelp T, Holm AF, Blom H, Mulder PG, Vroom TM, Rijntjes E. Dynamics of mast cells in the nasal mucosa of patients with allergic rhinitis and non-allergic controls: a biopsy study. Clin Exp Allergy. 1992;22:701–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1992.tb00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nouri-Aria KT, Pilette C, Jacobson MR, Watanabe H, Durham SR. IL-9 and c-Kit+ mast cells in allergic rhinitis during seasonal allergen exposure: effect of immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:73–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brightling CE, Bradding P, Symon FA, Holgate ST, Wardlaw AJ, Pavord ID. Mast-cell infiltration of airway smooth muscle in asthma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1699–705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll NG, Mutavdzic S, James AL. Increased mast cells and neutrophils in submucosal mucous glands and mucus plugging in patients with asthma. Thorax. 2002;57:677–82. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.8.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daugherty BL, Siciliano SJ, DeMartino JA, Malkowitz L, Sirotina A, Springer MS. Cloning, expression, and characterization of the human eosinophil eotaxin receptor. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2349–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Combadiere C, Ahuja SK, Murphy PM. Cloning and functional expression of a human eosinophil CC chemokine receptor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponath PD, Qin S, Post TW, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a human eotaxin receptor expressed selectively on eosinophils. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2437–48. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uguccioni M, Mackay CR, Ochensberger B, et al. High expression of the chemokine receptor CCR3 in human blood basophils. Role in activation by eotaxin, MCP-4, and other chemokines. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1137–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI119624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sallusto F, Mackay CR, Lanzavecchia A. Selective expression of the eotaxin receptor CCR3 by human T helper 2 cells. Science. 1997;277:2005–7. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saunders R, Sutcliffe A, Woodman L, et al. The airway smooth muscle CCR3/CCL11 axis is inhibited by mast cells. Allergy. 2008;63:1148–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romagnani P, de Paulis A, Beltrame C, Annunziato F, Dente V, Maggi E, Romagnani S, Marone G. Tryptase-chymase double-positive human mast cells express the eotaxin receptor CCR3 and are attracted by CCR3-binding chemokines. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1195–204. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65222-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Paulis A, Annunziato F, Di Gioia L, Romagnani S, Carfora M, Beltrame C, Marone G, Romagnani P. Expression of the chemokine receptor CCR3 on human mast cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2001;124:146–50. doi: 10.1159/000053694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ochi H, Hirani WM, Yuan Q, Friend DS, Austen KF, Boyce JA. T helper cell type 2 cytokine-mediated comitogenic responses and CCR3 expression during differentiation of human mast cells in vitro. J Exp Med. 1999;190:267–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brightling CE, Kaur D, Berger P, Morgan AJ, Wardlaw AJ, Bradding P. Differential expression of CCR3 and CXCR3 by human lung and bone marrow-derived mast cells: implications for tissue mast cell migration. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:759–66. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0904511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price KS, Friend DS, Mellor EA, De Jesus N, Watts GF, Boyce JA. CC chemokine receptor 3 mobilizes to the surface of human mast cells and potentiates immunoglobulin E-dependent generation of interleukin 13. Am J Respir. 2003;28:420–7. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0155OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliveira SH, Lukacs NW. Stem cell factor and IgE-stimulated murine mast cells produce chemokines (CCL2, CCL17, CCL22) and express chemokine receptors. Inflamm Res. 2001;50:168–74. doi: 10.1007/s000110050741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Li L, Wadley R, et al. Mast cells/basophils in the peripheral blood of allergic individuals who are HIV-1 susceptible due to their surface expression of CD4 and the chemokine receptors CCR3, CCR5, and CXCR4. Blood. 2001;97:3484–90. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humbles AA, Lu B, Friend DS, et al. The murine CCR3 receptor regulates both the role of eosinophils and mast cells in allergen-induced airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1479–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261462598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma W, Bryce PJ, Humbles AA, et al. CCR3 is essential for skin eosinophilia and airway hyperresponsiveness in a murine model of allergic skin inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:621–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI14097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurish MF, Humbles A, Tao H, Finkelstein S, Boyce JA, Gerard C, Friend DS, Austen KF. CCR3 is required for tissue eosinophilia and larval cytotoxicity after infection with Trichinella spiralis. J Immunol. 2002;168:5730–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abonia JP, Austen KF, Rollins BJ, Joshi SK, Flavell RA, Kuziel WA, Koni PA, Gurish MF. Constitutive homing of mast cell progenitors to the intestine depends on autologous expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR2. Blood. 2005;105:4308–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hallgren J, Jones TG, Abonia JP, Xing W, Humbles A, Austen KF, Gurish MF. Pulmonary CXCR2 regulates VCAM-1 and antigen-induced recruitment of mast cell progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20478–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709651104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peled A, Gonzalo JA, Lloyd C, Gutierrez-Ramos JC. The chemotactic cytokine eotaxin acts as a granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor during lung inflammation. Blood. 1998;91:909–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quackenbush EJ, Wershil BK, Aguirre V, Gutierrez-Ramos JC. Eotaxin modulates myelopoiesis and mast cell development from embryonic hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 1998;92:887–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quackenbush EJ, Aguirre V, Wershil BK, Gutierrez-Ramos JC. Eotaxin influences the development of embryonic hematopoietic progenitors in the mouse. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:661–6. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyazaki D, Nakamura T, Ohbayashi M, et al. Ablation of type I hypersensitivity in experimental allergic conjunctivitis by eotaxin-1/CCR3 blockade. Int Immunol. 2009;21:187–201. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weller CL, Collington SJ, Brown JK, et al. Leukotriene B4, an activation product of mast cells, is a chemoattractant for their progenitors. J Exp Med. 2005;201:961–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weller CL, Collington SJ, Hartnell A, et al. Chemotactic action of prostaglandin E2 on mouse mast cells acting via the PGE2 receptor 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11712–17. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701700104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz LB, Austen KF, Wasserman SI. Immunologic release of beta-hexosaminidase and beta-glucuronidase from purified rat serosal mast cells. J Immunol. 1979;123:1445–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzalo JA, Lloyd CM, Kremer L, Finger E, Martinez A, Siegelman MH, Cybulsky M, Gutierrez-Ramos JC. Eosinophil recruitment to the lung in a murine model of allergic inflammation. The role of T cells, chemokines, and adhesion receptors. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2332–45. doi: 10.1172/JCI119045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ikeda RK, Miller M, Nayar J, et al. Accumulation of peribronchial mast cells in a mouse model of ovalbumin allergen induced chronic airway inflammation: modulation by immunostimulatory DNA sequences. J Immunol. 2003;171:4860–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meininger CJ, Yano H, Rottapel R, Bernstein A, Zsebo KM, Zetter BR. The c-kit receptor ligand functions as a mast cell chemoattractant. Blood. 1992;79:958–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nilsson G, Butterfield JH, Nilsson K, Siegbahn A. Stem cell factor is a chemotactic factor for human mast cells. J Immunol. 1994;153:3717–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen CC, Grimbaldeston MA, Tsai M, Weissman IL, Galli SJ. Identification of mast cell progenitors in adult mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11408–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504197102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pennock JL, Grencis RK. In vivo exit of c-kit+/CD49d(hi)/beta7+ mucosal mast cell precursors from the bone marrow following infection with the intestinal nematode Trichinella spiralis. Blood. 2004;103:2655–60. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ying S, Robinson DS, Meng Q, et al. Enhanced expression of eotaxin and CCR3 mRNA and protein in atopic asthma. Association with airway hyperresponsiveness and predominant co-localization of eotaxin mRNA to bronchial epithelial and endothelial cells. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:3507–16. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]