Odontogenic Cysts

The classification system for odontogenic cysts tends to be quite complex, which can create confusion for the both the clinician and pathologist alike. Traditionally, these cysts have been divided into two major groups based on whether the lesion arises de novo or develops secondary to an inflammatory process (Table 1). This discussion will update the clinical and pathologic features of several of the more interesting developmental odontogenic cysts.

Table 1.

Odontogenic cysts

| Developmental |

| 1. Dentigerous cyst |

| 2. Eruption cyst |

| 3. Odontogenic keratocyst (keratocystic odontogenic tumor*) |

| 4. Orthokeratinized odontogenic cyst |

| 5. Gingival cyst of the newborn |

| 6. Gingival cyst of the adult |

| 7. Lateral periodontal cyst |

| 8. Glandular odontogenic cyst |

| Inflammatory origin |

| 1. Periapical cyst (radicular cyst; apical periodontal cyst) |

| 2. Residual periapical (radicular) cyst |

| 3. Buccal bifurcation cyst |

Odontogenic Keratocyst

Almost any pathologic classification scheme is guaranteed to generate some controversy, and the nosology of odontogenic cysts is no exception. Since its initial description by Philipsen in 1956, the odontogenic keratocyst has become well-known for its potential for aggressive behavior—so much so, that some pathologists and clinicians have begun to consider this lesion to be a neoplasm rather than simply a cyst. Recent molecular studies showing loss of heterozygosity of certain tumor suppressor genes in many odontogenic keratocysts have supported this opinion, and the most recent World Health Organization classification has renamed this lesion the “keratocystic odontogenic tumor.” However, only time will tell whether this new name will become accepted, especially since the term “odontogenic keratocyst” has become so ingrained in the literature.

Gingival Cyst of the Adult

The gingival cyst of the adult is a developmental odontogenic cyst believed to arise from rests of the dental lamina (rests of Serres) in the gingival soft tissues. These uncommon lesions have a striking predilection for the mandibular canine/premolar area, which accounts for nearly 75% of cases. Maxillary examples also are found most frequently in the canine/premolar region, as well as the lateral incisor area (Fig. 1). The gingival cyst of the adult usually occurs in middle-aged and older patients, most often in the fifth and sixth decades of life. The reason why such developmental cysts should occur in this location at this age of life is unexplained.

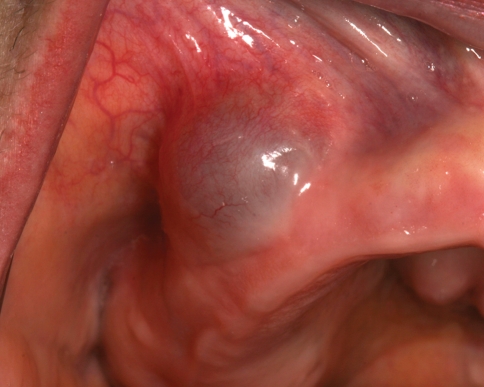

Fig. 1.

Gingival cyst of the adult. A blue, fluctuant swelling of the right maxillary buccal alveolar mucosa

Microscopically, the diagnosis of the gingival cyst of the adult is usually straightforward. The cystic cavity is lined by a thin layer of flattened epithelial cells ranging from one to three cells in thickness. In many cases, this lining will demonstrate occasional plaque-like or nodular thickenings that often include cells with a clear cytoplasm (Fig. 2). The cells in these thickened areas sometimes demonstrate a swirling appearance. The clear cells often contain glycogen, as demonstrated by periodic acid-Schiff staining, with and without prior diastase digestion.

Fig. 2.

Gingival cyst of the adult. This medium power photomicrograph shows the top of a cyst at the base of the specimen within the lamina propria. The cyst is lined by a thin, flattened layer of epithelial cells exhibiting a central nodular thickening

The differential diagnosis of the gingival cyst of the adult is not difficult. Occasional examples of peripheral odontogenic keratocyst have been described in the gingival soft tissues, but such lesions are easily distinguished by a thicker, uniform lining of four to eight cells, a palisaded basal layer of cuboidal/columnar cells, and presence of a corrugated layer of parakeratin on the epithelial surface. Probably the most difficult problem in diagnosis arises in small examples that exhibit only a small focal epithelial lining near the base of the specimen. If no plaque-like thickenings are present, it can be easy to overlook the remarkably thin, flattened lining, especially in cases where this lining separates from the cyst wall.

Lateral Periodontal Cyst

The lateral periodontal cyst is a developmental odontogenic cyst that arises between the roots of teeth. For many years, this term was used generally to describe any odontogenic cyst that occurred in the interradicular area, including lateral radicular cysts and odontogenic keratocysts. However, the lateral periodontal cyst has unique clinical and histopathologic features that distinguish it from these other cysts. It is believed to arise from remnants of the dental lamina (rests of Serres) that are found in the alveolar bone surrounding the tooth roots.

The lateral periodontal cyst shares many clinical features with the gingival cyst of the adult, including a predilection for middle-aged and older patients. The most frequent location is the mandibular canine/premolar area, which accounts for two-thirds of all cases. Maxillary examples also are found in this same region. Lateral periodontal cysts also may occur in the incisor area, but they are distinctly rare in the posterior regions of the jaws. Radiographically, the lesion typically presents as a well-circumscribed unilocular radiolucency between the tooth roots (Fig. 3). Multiple separate lateral periodontal cysts occasionally have been observed.

Fig. 3.

Lateral periodontal cyst. A well-circumscribed ovoid radiolucency is located between the roots of the premolar teeth (Courtesy of Dr. Jeff Johnson)

Microscopically, the lateral periodontal cyst is lined by a thin epithelial layer ranging from one to three cells in thickness. The lining also often shows plaque-like epithelial thickenings that may include swirling groups of glycogen-containing clear cells (Fig. 4). However, these thickenings may be subtle or absent in some cases. Some examples show a polycystic gross or microscopic appearance that can resemble a small cluster of grapes (botryoid odontogenic cyst). Such cases may demonstrate a multilocular radiolucent pattern that suggests one of the more aggressive odontogenic lesions, such as ameloblastoma or odontogenic keratocyst.

Fig. 4.

Lateral periodontal cyst. This medium power photomicrograph shows a cyst lined by a thin layer of epithelium that is 1–3 cells thick. A characteristic nodular, plaque-like thickening is seen at the bottom left

It readily becomes apparent that the gingival cyst of the adult and the lateral periodontal cyst are one and the same lesion, the only difference being whether the lesion occurs in soft tissue or bone. Indeed, some examples occur partially within bone and partially in soft tissue, which makes categorization difficult. Based on our current understanding, it would simplify matters to classify both lesions under a common name. Because it is generally accepted that these cysts are derived from remnants of dental lamina, one possible solution would be to use “dental lamina cyst” preceded by either “central” or “peripheral” depending on whether the lesion arose primarily in bone or in soft tissue. However, because all odontogenic epithelium is originally derived from dental lamina, it could be argued that such a term is not specific enough. Another option would be to use “lateral periodontal cyst” for both lesions, possibly with a “peripheral” modifier for the extraosseous gingival examples.

Glandular Odontogenic Cyst

The glandular odontogenic cyst is the most recently recognized type of developmental odontogenic cyst. Originally known as a sialo-odontogenic cyst because of its salivary features, this lesion demonstrates the pluripotentiality of the odontogenic epithelium.

The glandular odontogenic cyst most frequently occurs in middle-aged adults and has a predilection for the anterior mandible, with many cases crossing the midline. Many examples of so-called “median mandibular cyst” probably represent glandular odontogenic cysts. Maxillary examples also are seen most often in the anterior region. The clinical presentation is highly variable, ranging from small, asymptomatic unilocular cysts less than 1 cm in diameter to large, expansile, multilocular lesions that destroy much of the jaw (Fig. 5).

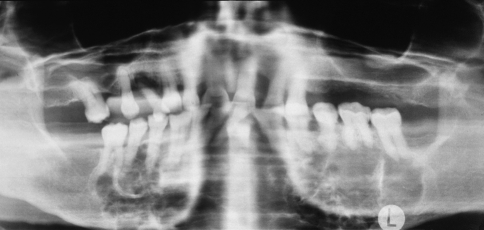

Fig. 5.

Glandular odontogenic cyst. A large, expansile, multilocular radiolucency involves the entire body of the mandible from molar to molar

Microscopic examination reveals a basic lining of stratified squamous epithelium that is variable in thickness. However, the superficial cells tend to be cuboidal to columnar in shape, often with an irregular, papillary surface. Within the epithelium are occasional gland-like spaces that are lined by similar cuboidal/columnar cells (Fig 6). Mucin-producing cells and cilia sometimes can be identified. Pools of mucicarminophilic material can be found within the gland-like spaces. Some areas of the lining may form spherical aggregates of swirling epithelial cells reminiscent of the pattern observed in the lateral periodontal cyst. This finding lends support for an odontogenic origin of this lesion, and also suggests a similar histogenesis.

Fig. 6.

Glandular odontogenic cyst. This medium-high power photomicrograph shows a cyst lined by stratified squamous epithelium with a surface layer of eosinophilic columnar cells. Note the intraepithelial gland-like spaces, which are also lined by these cuboidal/columnar cells

Although relatively few examples of glandular odontogenic cyst have been reported, this lesion is already well-known for its aggressive growth potential and significant recurrence rate, which appears equal or higher than that of the odontogenic keratocyst. Because of this, some authors have advocated en bloc resection for many of these lesions.

The differential diagnosis for the glandular odontogenic cyst includes a low-grade intraosseous mucoepidermoid carcinoma. However, the epithelial lining of the glandular odontogenic cyst is usually thinner, and the lesion does not exhibit the solid and microcystic areas of epithelial growth encountered in mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma also does not exhibit swirling spherical epithelial aggregates, which may be a feature of glandular odontogenic cyst. However, the presence of such aggregates may cause confusion with a lateral periodontal cyst, especially when examining a small incisional biopsy from a larger lesion.

Unusual Mucosal Conditions

One of the fascinating aspects about the oral mucosa is its ability to provide clues that can lead to the diagnosis of significant systemic pathology. The purpose of this part of the seminar is to review the clinical and histopathologic features of two of these interesting conditions.

Pyostomatitis Vegetans

Pyostomatitis vegetans is a rare oral mucosal eruption that is a sign of inflammatory bowel disease. It is most frequently associated with ulcerative colitis, although some examples are related to Crohn disease. The condition is characterized by multiple slightly elevated yellowish pustules that often are arranged in linear, serpentine fashion that has been likened to a “snail track” (Fig. 7). The mucosal background is usually red and edematous. In spite of its rather dramatic clinical appearance, pain and discomfort are often surprisingly minimal. Although the diagnosis of the related bowel disease may already be known, sometimes the oral lesions can be the first sign that leads to the diagnosis. Some patients also may develop a vesiculopustular skin eruption, known as pyodermatitis vegetans.

Fig. 7.

Pyostomatitis vegetans. Multiple yellow pustules can be seen on the right buccal mucosa

The microscopic features are quite characteristic, consisting of an intense infiltrate of eosinophils into the epithelium, resulting in intraepithelial abscess formation (Fig. 8). The spinous cells often demonstrate intercellular edema with acantholysis. In some cases, both intraepithelial and subepithelial abscess formation will be observed. A heavy mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with numerous eosinophils is also present in the lamina propria.

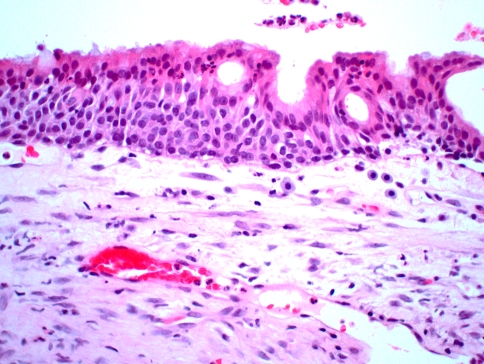

Fig. 8.

Pyostomatitis vegetans. This medium power photomicrograph shows an intraepithelial abscess of eosinophils and neutrophils

Because of the acantholysis and presence of eosinophils, the differential diagnosis may include pemphigus vulgaris. However, the intensity of the eosinophils is much greater than is typically observed in pemphigus lesions, and immunofluorescent studies are usually negative or inconsistent with pemphigus.

For patients with pyostomatitis vegetans, management of the underlying bowel disease is usually of greatest concern. Systemic corticosteroids usually result in rapid resolution of the oral lesions, sometimes within a matter of days. If the bowel disease is mild and does not require treatment, potent topical corticosteroid therapy also has been reported to be effective.

Wegener’s Granulomatosis

Wegener’s granulomatosis is an uncommon inflammatory disease of unknown cause, which often involves multiple organ systems. Classic features include necrotizing granulomatous lesions of both the upper and lower respiratory tract, plus necrotizing glomerulonephritis. Upper respiratory symptoms consist of purulent nasal drainage, congestion, and pain, which may lead to ulceration and destruction of the nasal septum. Less frequently, oral ulcerations may occur. Bone destruction and palatal ulcerations can develop from direct extension of sinonasal lesions, leading to oral/nasal or oral/antral fistulas. Less severe “limited” and “superficial” patterns of Wegener’s granulomatosis also may occur.

A rare, but highly distinctive, oral manifestation is development of hyperplastic gingivae known as “strawberry gingivitis.” The gingival enlargement exhibits a reddish purple, granular surface that is friable and hemorrhagic. Strawberry gingivitis can be an early sign of Wegener’s granulomatosis, often developing prior to renal involvement.

Most patients with generalized disease will exhibit the presence of cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasm antibodies (c-ANCA) on indirect immunofluorescence. However, in patients with limited or superficial involvement, such as strawberry gingivitis, these antibodies may not be found.

Wegener’s granulomatosis is characterized by a mixed inflammatory infiltrate that is often centered around blood vessels. This inflammation includes histiocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and multinucleated giant cells. Transmural inflammation of vessel walls (leukocytoclastic vasculitis) can lead to local tissue necrosis.

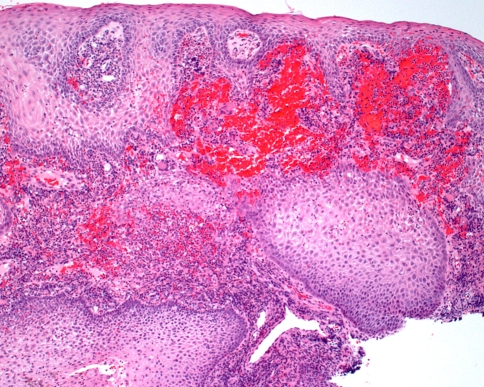

Because significant inflammation is such a common finding in many gingival specimens, the possibility of Wegener’s granulomatosis can be easily overlooked. However, the combination of several features is highly suggestive of the diagnosis. First, there is prominent hemorrhage in the superficial connective tissue, which corresponds to the petechial appearance observed clinically (Fig. 9). Second, the overlying epithelium often demonstrates striking pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. A heavy inflammatory infiltrate is present, which includes numerous eosinophils and scattered multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 10). Neutrophilic abscesses sometimes are seen within the epithelium. Because few large blood vessels are present within the gingiva, it may be difficult to demonstrate the presence of classic vasculitis.

Fig. 9.

Wegener’s granulomatosis. This low power photomicrograph from a gingival lesion demonstrates pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epithelium with prominent subepithelial hemorrhage

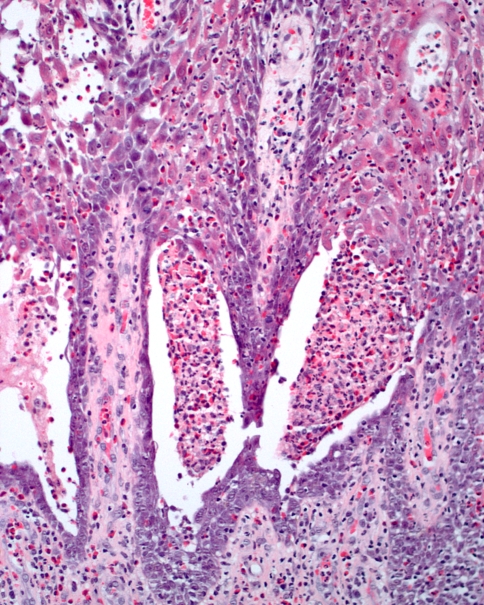

Fig. 10.

Wegener’s granulomatosis. High power photomicrograph revealing an intense mixed inflammatory infiltrate that includes multinucleated giant cells, eosinophils, and hemorrhage

The prognosis for patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis has greatly improved with modern drug therapy, which often includes a combination of cyclophosphamide and prednisone. Lesions of strawberry gingivitis usually respond well to this regimen.

Bibliography

Odontogenic Keratocyst

- 1.Agaram NP, Collins BM, Barnes L, et al. Molecular analysis to demonstrate that odontogenic keratocysts are neoplastic. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:313–7. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-313-MATDTO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahlfors E, Larsson A, Sjögren S. The odontogenic keratocyst: a benign cystic tumor? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;42:10–9. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(84)90390-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daley TD, Multari J, Darling MR. A case report of a solid keratocystic odontogenic tumor: is it the missing link? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:512–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henley J, Summerlin DJ, Tomich C, et al. Molecular evidence supporting the neoplastic nature of odontogenic keratocyst: a laser capture microdissection study of 15 cases. Histopathology. 2005;47:582–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Philipsen HP. Om keratocyster (kolesteatomer) i kaeberne. Tandlaegebladet. 1956;60:963. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shear M. The aggressive nature of the odontogenic keratocyst: is it a benign cystic neoplasm? Part. 2. Proliferation and genetic studies. Oral Oncol. 2002;38:323–31. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(01)00066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gingival Cyst of the Adult

- 7.Buchner A, Hansen LS. The histomorphologic spectrum of the gingival cyst in the adult. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1979;48:532–9. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(79)90300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cairo F, Rotundo R, Ficarra G. A rare lesion of the periodontium: the gingival cyst of the adult—a report of three cases. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2002;22:79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giunta JL. Gingival cysts in the adult. J Periodontol. 2002;73:827–31. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.7.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nxumalo TN, Shear M. Gingival cyst in adults. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:309–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wysocki GP, Brannon RB, Gardner DG, et al. Histogenesis of the lateral periodontal cyst and the gingival cyst of the adult. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980;50:327–334. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(80)90417-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lateral Periodontal Cyst

- 12.Carter LC, Carney YL, Perez-Pudlewski D. Lateral periodontal cyst: multifactorial analysis of a previously unreported series. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:210–6. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(96)80417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen D, Neville B, Damm D, et al. The lateral periodontal cyst: a report of 37 cases. J Periodontol. 1984;55:230–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.1984.55.4.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fantasia JE. Lateral periodontal cyst. An analysis of forty-six cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1979;48:237–43. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(79)90010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurol M, Burkes EJ, Jr, Jacoway J. Botryoid odontogenic cyst: analysis of 33 cases. J Periodontol. 1995;66:1069–73. doi: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.12.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramer M, Valauri D. Multicystic lateral periodontal cyst and botryoid odontogenic cyst. Multifactorial analysis of previously unreported series and review of literature. NY State Dent J. 2005;71:47–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wysocki GP, Brannon RB, Gardner DG, et al. Histogenesis of the lateral periodontal cyst and the gingival cyst of the adult. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980;50:327–34. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(80)90417-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Glandular Odontogenic Cyst

- 18.Hussain K, Edmondson HD, Browne RM. Glandular odontogenic cysts. Diagnosis and treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79:593–602. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(05)80101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan I, Gal G, Anavi Y, et al. Glandular odontogenic cyst: treatment and recurrence. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:435–41. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noffke C, Raubenheimer EJ. The glandular odontogenic cyst: clinical and radiological features; review of the literature and report of nine cases. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002;31:333–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin XN, Li JR, Chen XM, et al. The glandular odontogenic cyst: clinicopathologic features and treatment of 14 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:694–99. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pyostomatitis Vegetans

- 22.Ahn BK, Kim S-C. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans with circulating autoantibodies to bullous pemphigoid antigen 230. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:785–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markiewicz M, Suresh L, Margarone J, 3rd, et al. Pyostomatitis vegetans: a clinical marker of silent ulcerative colitis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:346–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neville BW, Laden SA, Smith SE, et al. Pyostomatitis vegetans. Am J Dermatopathol. 1985;7:69–77. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198502000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nigen S, Poulin Y, Rochette L, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans: two cases and a review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7:250–5. doi: 10.1007/s10227-002-0112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wegener’s Granulomatosis

- 26.Allen CM, Camisa C, Salewski C, et al. Wegener’s granulomatosis: report of three cases with oral lesions. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:294–8. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90224-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ponniah I, Shaheen A, Shankar KA, et al. Wegener’s granulomatosis: the current understanding. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:265–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart C, Cohen D, Bhattacharyya I, et al. Oral manifestations of Wegener’s granulomatosis. A report of three cases and a literature review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:338–48. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]