Abstract

Context Oral verrucous carcinoma (OVC) and oral verrucous hyperplasia (OVH) may be clinically and histologically similar. Problems separating these lesions are compounded by poorly oriented tissue sections and biopsies failing to demonstrate lesional margins. Objective To distinguish OVC from OVH utilizing an immunohistochemical panel (p53, matrix metalloproteinase-1, E-cadherin, Ki67) shown to be useful in differentiating pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from oral squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Materials Twenty-eight cases of OVH and thirty-two cases of OVC studied. Diagnoses were confirmed by two pathologists. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded archival material was used for immunohistochemistry (avidin–biotin immunoperoxidase technique). Results More diffuse nuclear staining of p53 and Ki67 was detected in the OVC cases compared to the OVH cases (P < 0.001). There was statistically significant increased staining within adjacent stromal cells for matrix metalloproteinase-1 (P < .05) in the OVC cases. E-cadherin demonstrated diffuse membranous staining in both groups. Conclusion Ki67, p53, and MMP-1 demonstrated significant staining trends. Although a properly oriented hematoxylin–eosin-stained section including normal marginal tissue is considered to be the gold standard for differentiation of OVH and OVC, this immunohistochemistry panel may serve as a useful diagnostic adjunct in difficult cases.

Keywords: Verrucous hyperplasia, Verrucous carcinoma, Immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Distinguishing oral verrucous carcinoma (OVC) from oral verrucous hyperplasia (OVH) can be difficult. These entities may be clinically identical and histologic separation may be made difficult due to small specimen size, poor orientation, and failure to sample the lesional margin. Utilizing immunohistochemical stains for p53, matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1), E-cadherin, and Ki67, we attempted to distinguish OVC from OVH. Each of these markers has been studied independently in head and neck neoplasia and is significant in the neoplastic process. A similar panel has been shown to be useful in differentiating invasive adenocarcinoma in colonic adenomas from displaced adenomatous epithelium as well as separating pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from squamous cell carcinoma in head and neck specimens [1, 2].

Materials and Methods

The archives of the Oral Pathology Department at the University of Toronto and the Pathology Department at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre were searched for oral mucosal biopsies with the diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma or verrucous hyperplasia between 1987 and 2006. Tissue blocks were inspected to ensure that adequate tissue quantities remained. One case diagnosed as OVC and one case diagnosed as OVH were eliminated for this reason.

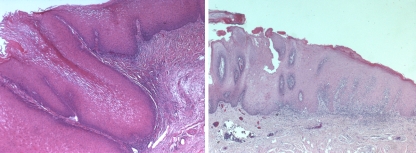

The specimens included excisional and incisional biopsies. For incisional biopsies (n = 6), the pathology reports of the excisional biopsy were reviewed to confirm the diagnosis. Specimen sizes ranged from 0.6×0.4×0.3 cm3 to 2.5×2.2×1.1 cm3. All specimens were submitted in toto for microscopic examination. Hematoxylin-eosin-stained sections were reviewed by two pathologists to ensure conformity with accepted diagnostic criteria. All specimens contained the lesion margin and underlying connective tissue. We used the following diagnostic criteria for OVC: a well-differentiated bland proliferation of squamous epithelium without dysplasia, broad bulbous rete pegs with a pushing margin, and marked surface keratinization. A mixed chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate may also be prominent in the stroma [3] (Fig. 1, left). We used Shear and Pindborg’s description of both the short and blunt forms of OVH. In both forms, hyperplastic epithelium and verrucal surface projections are preponderantly superficial to the adjacent epithelium. In the sharp form, the projections are long, narrow and heavily keratinized, whereas the blunt form has less keratinization and shorter, more blunt projections [4] (Fig. 1, right). The major difference in the definitions used of OVC versus OVH is that in the former the projections of neoplastic epithelium are seen deep to the adjacent uninvolved epithelium whereas in OVH they are seen only to the same level as adjacent epithelium.

Fig. 1.

Verrucous Carcinoma (left) demonstrates well-differentiated squamous epithelium with broad, pushing bulbous rete pegs and marked surface keratinization. Verrucous Hyperplasia (right) shows hyperplastic squamous epithelium with broad and blunt rete ridges, and verrucal surface projections, which are superficial to the adjacent epithelium (H + E, original magnification ×5)

Histologic diagnosis was assigned blinded to the original diagnosis. A case originally identified as OVH was eliminated from the study as it was believed to better fulfill the criteria for verruciform xanthoma. Additionally, four cases of OVH and two cases of OVC were eliminated because the biopsies were insufficient to fulfill diagnostic criteria. Twenty-eight cases of OVH and thirty-two cases of OVC remained from different patients.

The tissues were immunostained with monoclonal antibodies against p53 (1:400, Novocastra, Newcastle, UK), MMP-1 (1:40, Calbiochem, California, USA), E-cadherin (1:2000, B-D Sciences, Ontario, Canada), and Ki67 (1:400, Neomarker, California, USA) with the avidin–biotin complex technique, using appropriate positive and negative controls. Quantitative interpretations were made for each stain by the authors by consensus. The stained slides were examined by light microscopy and graded as follows for p53, Ki67 and E-cadherin: “0” indicated absence of brown precipitate in cells; the positives were labeled as “1” if there was staining in the basal cell layer only; “2” for positive staining in the supra basal cells limited to the lower half of the epithelium, and “3” for positive staining in the supra basal cells in the upper half of the epithelium. For MMP-1, staining of the adjacent stromal cells graded as absent (0) or present (1). Appropriate positive and negative controls were reviewed. Invasive ductal carcinoma of the human breast was used as positive control tissue for MMP-1 immunohistochemistry. Negative controls involved omission of the primary antibody.

The descriptive statistics were analyzed with a Statistic Program for Social Sciences (SPSS) in Microsoft Excel. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used for appropriate P values.

Results

OVH patients ranged in age from 45 to 82 years (mean age, 61 years). The age range in patients with OVC was 56–79 years (mean age, 66 years). The male–female ratio was 1:1.2 and 1:1.4 for OVH and OVC patients, respectively. Most cases of OVH were located on the gingiva (67.9%) with others located on the buccal mucosa (17.9%), tongue (3.6%) and palate (3.6%), with two cases of unspecified location. Most cases of OVC were located on the gingival (43.8%) and buccal mucosa (28.1%) with the remainder located on the hard palate (15.6%) and four cases unspecified.

Immunohistochemical findings are summarized in Table 1 and illustrated in Figs. 2–4. The major finding was that for both p53 and Ki67, there was a general trend for a more diffuse staining pattern in OVC compared to OVH. For p53, finding staining above the basal layer was exceptional in OVH (<5% of cases) while common in OVC (more than half of the cases studied). For Ki67, staining of the upper half of the epithelium was only found in OVC. These differences were significant at the P < 0.001 level.

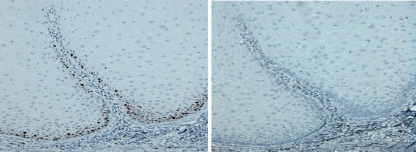

Fig. 3.

Verrucous Hyperplasia: Ki67 (left) and p53 (right). Ki67 expression is limited to the basal cell layer (grade 1), while there is absent p53 expression (grade 0) (original magnification ×20)

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical expression for p53, Ki67 and E-cadherin in oral verrucous hyperplasia (OVH) and oral verrucous carcinoma (OVC)

| Ki67 (%) | p53 (%) | E-Cadherin (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OVH | OVC | OVH | OVC | OVH | OVC | |

| 0 | 3.6 | 0 | 32.1 | 9.4 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 53.5 | 6.3 | 64.3 | 34.4 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 42.9 | 78.1 | 3.6 | 56.2 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 15.6 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

0 = absent staining, positive staining, 1 = basal cell layer, 2 = supra basal cell layer, 3 = diffuse

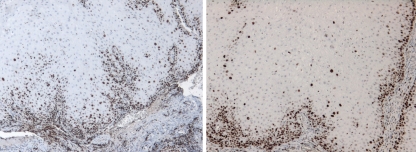

Fig. 2.

Verrucous Carcinoma: Ki67 (left) and p53 (right). Expression of both markers in the basal cell layer and supra basal cells, grade 2 (original magnification ×10)

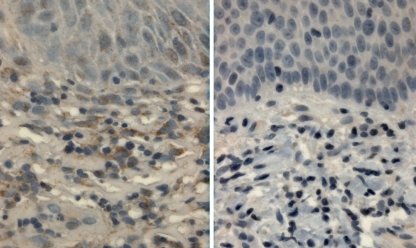

Fig. 4.

MMP-1 expression. Verrucous carcinoma (left) demonstrates expression in the underlying stromal cells and a background staining in the epithelium. Verrucous hyperplasia lacks expression in underlying stromal cells (original magnification ×40)

OVC cases showed nuclear reactivity for p53 in 90.6% of cases compared to 67.9% of OVH cases. Most OVC cases showed staining of the basal cell layer (34.4%) and supra basal cells (56.3%). OVH cases showed staining predominantly limited to the basal cell layer (64.3%). For Ki67, OVC cases predominantly showed staining in the lower half of the epithelium (78.1%) with some cases also showing scattered positive cells in the upper half of the epithelium (15.6%). OVH cases showed staining in the basal cell layer (53.5%) and lower half of the epithelium (42.9%).

All cases of OVH and OVC displayed uniform membranous staining for E-cadherin throughout the entire epithelial thickness.

About 68.8% of OVC showed staining of stromal cells for MMP-1 in the superficial lamina propria compared to 35.7% of OVH cases, a difference that was statistically significant (P < 0.05). MMP-1 staining within the epithelium was not observed.

Normal squamous epithelium served as the control for all analyses. Ki67 and p53 lacked expression in normal epithelium whereas E-cadherin showed diffuse membranous staining. Five percent of control cases showed stromal cell staining for MMP-1.

Discussion

Verrucous carcinoma (OVC) is a low-grade variant of SCC characterized by locally aggressive growth and rare metastasis [5]. OVC is reported to metastasize to lymph node and distant sites, while adjacent structures are often involved with time and growth of the primary tumor. OVH is a potentially precancerous lesion, often regarded as a precursor of OVC and considered by some to be in a spectrum towards conventional SCC. The traditional treatment for OVH is total surgical excision or observation. The treatment of oral VC remains controversial, although many investigators have recommended surgery as the treatment of choice for OVC since some studies suggested that anaplastic transformation of the tumor could occur after radiotherapy [5].

OVH may resemble OVC both clinically and histologically. The most reliable way to separate these entities on routine hematoxylin–eosin-stained tissue sections is based on distinguishing the exophytic growth pattern of OVH, from the endophytic and invasive growth pattern associated with OVC. A properly oriented hematoxylin–eosin-stained section is the gold standard for such distinction, however, separation of these lesions is often obscured by small biopsies, poorly orientated specimens, and most notably, biopsies that fail to demonstrate the lesional margin. The goal of this study was to determine whether a panel of immunohistochemical stains could be utilized as an adjunct to routine hematoxylin-eosin staining to distinguish OVC from OVH.

We evaluated p53, Ki67, MMP-1, and E-cadherin expression as a similar panel has been shown useful in differentiating invasive adenocarcinoma in colonic adenomas from displaced adenomatous epithelium [2]. Invasive adenocarcinomas were found to display significantly increased p53 and MMP-1 staining and decreased and discontinuous E-cadherin staining. A similar panel composed to separate SCC from pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in head and neck specimens found that p53, MMP-1, and E-cadherin showed significant staining trends [1]. Adegboyega et al. [6] have previously shown p53 and Ki67 to be helpful in distinguishing verrucous carcinoma from reactive epithelial hyperplasia.

p53, a tumor suppressor gene, is reported to be the most frequent target for genetic alterations leading to cancer, and the mutation has been demonstrated in epithelial neoplasms. Immunostaining for p53, an indicator of an abnormal accumulation of mutated p53, has been detected in the nuclei of several tumors, including OVC [7–9]. Wu et al. [10] reported p53 staining is significantly associated with the differentiation of squamous epithelial lesions with a greater degree of expression in SCC compared to OVH and OVC.

Expression of Ki67, a marker of proliferative activity, has been demonstrated to be diffuse throughout the entire thickness of the epithelium in invasive squamous carcinomas [9]. Non-dysplastic acanthotic epithelium, to the contrary, shows expression limited to the basal cell layer [8]. The increased proliferative activity observed in OVC compared to OVH illustrates a continuum between benign and malignant squamous epithelia.

Several MMPs have been implicated in cancer invasion. MMPs have been reported to be up-regulated during invasion in SCC, and in oral SCC, MMP-1 mRNA has been detected in fibroblastic cells of tumoral stroma [11–13]. MMP-1, also known as interstitial collagenase, is believed to be important for tumor invasion through collagenous stroma [12]. Our cases of OVC showed expression in the adjacent stromal cells in significantly more cases than OVH. This supports the role of collagenase activity in the invasive process of OVC. Caution, however should be used when interpreting MMP-1 results in a background of inflammation, which may affect its expression.

E-cadherin is an intercellular calcium-dependent cell adhesion molecule. E-cadherin expression has been found to be inversely associated with invasion, metastasis, and poor prognosis in head and neck SCC [14–17]. Expression in OVC (83.3%) has been reported to be significantly greater than that in poorly differentiated SCC (37.5%) [14]. Our cases showed diffuse membranous staining throughout the epithelium in all cases of both OVC and OVH indicating that disturbances of adhesion molecules appear to be a property of more severe and advanced neoplasia in this area.

To conclude, this study applied four markers (p53, E-cadherin, Ki67 and MMP-1) to cases of OVC and OVH by immunohistochemical methods. We found the pattern of p53, Ki67 and MMP-1 expression in OVC to be significantly different from that observed in OVH. Although a properly oriented hematoxylin–eosin-stained section demonstrating lesional margins remains the goal standard for separation of OVC and OVH, use of a p53, Ki67 and MMP-1 immunoperoxidase panel may be helpful as an adjunct in difficult cases with poorly oriented specimens.

References

- 1.Zarovnaya E, Black C. Distinguishing pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from squamous cell carcinoma in mucosal biopsy specimens from the head and neck. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129(8):1032–6. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-1032-DPHFSC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yantiss RK, Rosenberg MW, Odze RD. Utility of MMP-1, p53, E-cadherin, and collagen IV immunohistochemical stains in the differential diagnosis of adenomas with misplaced epithelium versus adenomas with invasive adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:206–15. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson N, Franceschi S, Slootweg PJ. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer Press; 2005. Squamous cell carcinoma. Pathology and genetics: head and neck tumors; pp. 175–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shear M, Pindborg JJ. Verrucous hyperplasia of the oral mucosa. Cancer. 1980;46:1855–62. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19801015)46:8<1855::AID-CNCR2820460825>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogawa A, Fukuta Y, Satoh M. Treatment results of oral verrucous carcinoma and its biological behavior. Oral Oncol. 2004;40(8):793–7. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adegboyega P, Boromound N, Freeman D. Diagnostic utility of cell cycle and apoptosis regulatory proteins in verrucous squamous carcinoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2005;13(2):171–7. doi: 10.1097/01.pai.0000132190.39351.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyle JO, Hakim J, Kock W. The incidence of p53 mutations increases with progression of head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;53:4477–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gimenez-Conti IB, Collet AM, Conti CJ. P53, Rb and cyclin D1 expression in human oral verrucous carcinomas. Cancer. 1996;8(1):17–23. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960701)78:1<17::AID-CNCR4>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito T, Nakajima T, Mogi K. Immunohistochemical analysis of cell cycle-associated proteins p16, pRb, p53, p27 and Ki67 in oral cancer and precancer with special reference to verrucous carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999;28(5):226–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1999.tb02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu M, Putti T, Bhuiya TA. Comparative study in the expression of p53, EGFR, TGF-[alpha], and Cyclin D1 in verrucous carcinoma, verrucous hyperplasia, and squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck region. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2002;10(4):351–6. doi: 10.1097/00022744-200212000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller D, Breathnach R, Engelmann A. Expression of collagenase-related metalloproteinase genes in human lung or head and neck tumors. Intern J Cancer. 1991;48:550–556. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910480412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Impola U, Uitto VJ, Saarialho-Kere U. Differential expression of matrilysin-1 (MMP-7), 92 kD gelatinase (MMP-9), and metalloelastase (MMP-12) in oral verrucous and squamous cell cancer. J Pathol. 2004;202(1):14–22. doi: 10.1002/path.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ono Y, Fujii M, Kanzaki J. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 mRNA related to eosinophilia and interleukin-5 gene expression in head and neck tumour tissue. Virchows Arch. 1997;431(5):305–10. doi: 10.1007/s004280050103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang ZG, Zou P, Xie XL. Expression of E-cadherin gene protein in oral verrucous carcinoma. Hunan yi ke da xue xue bao. 2003;28(3):206–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bankfalvi A, Krassort M, Piffko J. Gains and losses of adhesion molecules (CD44, E-cadherin, and β-catenin) during oral carcinogenesis and tumor progression. J Pathol. 2002;198:343–51. doi: 10.1002/path.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeh KT, Shih MC, Lin TH. The correlation between CpG methylation on promoter and protein expression of E-cadherin in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:3971–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka N, Odajima T, Satoh M. Expression of E-cadherin, α-catenin, and β-catenin in the process of lymph node metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:557–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]