Abstract

Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (BRONJ) is mainly observed in patients with multiple myeloma and bone metastasis from solid tumors receiving iv bisphosphonate therapy. The reported incidence of BRONJ is significantly higher with the iv preparations zoledronic acid and pamidronate while the risk appears to be minimal for patients receiving oral bisphosphonates. Currently available published incidence data for BRONJ are based on retrospective studies and estimates of cumulative incidence range from 0.8 to 12%. The mandible is more commonly affected than the maxilla (2:1 ratio), and 60–70% of cases are preceded by a dental surgical procedure. The signs and symptoms that may occur before the appearance of clinical evident osteonecrosis include changes in the health of periodontal tissues, non-healing mucosal ulcers, loose teeth and unexplained soft-tissue infection. Although the definitive role of bisphosphonates remains to be elucidated, the inhibition of physiologic bone remodeling and angiogenesis by these potent drugs impairs the regenerative capacity of the bone causing the development of BRONJ. Tooth extraction as a precipitating event is a common observation. The significant benefits that bisphosphonates offer to patients clearly surpass the risk of potential side effects; however, any patient for whom prolonged bisphosphonate therapy is indicated, should be provided with preventive dental care in order to minimize the risk of developing this severe condition. This article provides an update review of current knowledge about clinical, pathological and management aspects of BRONJ.

Keywords: Bisphosphonate, Osteonecrosis, Jaws, Osteomyelitis, Zoledronic acid, Pamidronate, Cancer, Bone metastasis, Osteoporosis, Review

Bone metastasis are a common occurrence in advanced cancer and can be responsible of several complications such as hypercalcemia, bone pain, pathologic fractures, limited mobility and spinal cord compression. Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates (intravenous zoledronic acid or pamidronate), together with other treatment options, are used widely for the treatment of these negative skeletal events [1]. In 2003, after an alert initial observation by Wang et al. [2] at the University of California San Francisco, Rosenberg and Ruggiero [3], Marx [4] and Migliorati [5] have reported unusual findings of osteomyelitis-like lesions of the jaws in a set of patients affected by multiple myeloma and metastatic bone disease; subsequently, several papers have confirmed the initial observations and called this condition bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (BRONJ) [6–24]. All the initial observations have pointed to the potential role of the intravenously administered bisphosphonates such as pamidronate and zoledronate. Additionally, BRONJ has been reported in a small number of patients (until now about 50 cases) who had received oral non-nitrogen or oral nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates for both cancer and non-cancerous conditions [6, 11, 17, 25–30]. Recently, Yarom et al. [31] have reported 11 cases of BRONJ induced by oral bisphosphonates. All cases developed in patients affected by osteoporosis who were treated with alendronate. The BRONJ lesions were triggered by dental surgery or by ill-fitting dentures and, in some patients, were aggravated by heavy smoking. Currently available published incidence data for BRONJ are based on retrospective studies and estimates of cumulative incidence range from 0.8 to 12%. Barmias et al. [32] have reported a high prevalence (9.9%) in myeloma patients. A recent survey of 1,086 oncology patients reported that 3.8% of multiple myeloma patients, 2.5% of breast cancer patients and 2.9% of prostate cancer developed BRONJ [33]. Of great relevance is a recent population-based study in which the data from the USA SEER program linked to Medicare claims were used [34]. The survey has identified 16,073 cancer patients treated with iv bisphosphonates between 1995 and 2003 who were matched with 28,698 bisphosphonate non-users. The conclusion of this study is that users of iv bisphosphonates had an increased risk of inflammatory conditions, osteomyelitis, and surgical procedures of the jaws and facial bones which may reflect an increased risk for BRONJ [34]. It is of historical interest to mention that osteonecrosis of the jaws was observed in the 19th and early 20th centuries in patients exposed to white phosphorus. At that time the disease was called phossy jaw or phosphorus necrosis and was mainly observed in people working in the matchmaking and fireworks factories or brass and war munitions industries [35]. Amazingly, clinical descriptions of phossy jaw lesions overlap those reported today in cases of BRONJ [36]. Osteonecrosis of the jaws caused by radiation is a well-recognized disease, which usually is well managed with a combination of hyperbaric oxygen and local surgery [37, 38]. Chemotherapy, although in rare cases, can also be a cause of osteonecrosis of the jaws. This entity however remains poorly understood [39].

This review provides an update on current knowledge about clinical, pathological and management aspects of BRONJ.

Clinical and Radiographic Features

Patients with BRONJ are typically oncology patients with multiple myeloma or metastatic disease involving bone. The clinical aspects and behavior of BRONJ show a striking resemblance to osteoradionecrosis with exposed bone and sequestration non-responsive to conventional surgical management. BRONJ may be asymptomatic for long time or may result in pain or exposed maxillary or mandibular bone (Fig. 1). Typical signs and symptoms are pain, soft-tissue swelling and infection, loosening of teeth and draining fistula. Patients may have other symptoms such as difficulty with eating, speaking, and clinical signs such as trismus, halitosis and recurrent abscesses. Some patients may present with atypical symptoms such as “dull pain”, numbness, the feeling of a “bigger jaw” or lower-lip paresthesia. The signs and symptoms that may occur before the appearance of clinically evident BRONJ include changes in the health of periodontal tissues, non-healing mucosal ulcers, loose teeth and unexplained soft-tissue infection [6, 10, 11]. Chronic maxillary sinusitis secondary to BRONJ with or without oro-antral fistula can be the presenting symptom in patients with maxillary involvement. Since 2003, more than 1,000 cases of BRONJ of the jaws have been reported in the English language literature, the majority associated with the use of iv bisphosphonates [19–21, 23]. Anatomic location may be unilateral or bilateral with 63–68% affecting only the mandible, 24–28% of cases involving only the maxilla, and 4.2% both jaws. The mean number of involved areas was 2.3 per each affected patient, with each site having an average size of 2 cm. Unusual cases of extragnatic location in the external auditory canal have been observed [40, Ficarra, personal observation]. Ruggiero et al. [6] have observed pathologic fracture of either the maxilla or mandible in 8% of patients treated with nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates; rare cases of bilateral pathologic fractures of both jaws also have been reported. Extraoral fistula formation and sequestration through the skin are infrequently observed. Sometimes the bone sequestra are spontaneously eliminated by the patients (Fig. 2). Radiographic alterations are not evident until there is significant bone involvement. Early stages of BRONJ may not reveal any significant changes on panoramic and periapical films. Late radiographic changes may mimic classic periapical inflammatory lesions or osteomyelitis. Other radiographic findings include non-healing extraction site, widening of the periodontal ligament space and osteosclerotic lamina dura (Fig. 3) [10, 17–19, 22]. In cases of extensive bone involvement, areas of mottled bone similar to that of diffuse osteomyelitis become evident (Fig. 4). In cancer patients some of these changes may raise the suspicion of myeloma or metastatic bone lesions [19]. Involvement of the inferior alveolar canal can be associated with paresthesia of the lower lip. Bone scan with Tc-99 m methylene diphosphonate often shows intense uptake in or around the lesional area, indicating active bone turnover.

Fig. 1.

Extensive osteonecrosis in the right maxilla with large sequestrum

Fig. 2.

Multiple small sequestra in the maxilla. These sequestra were spontaneously eliminated by the patient after 8 months

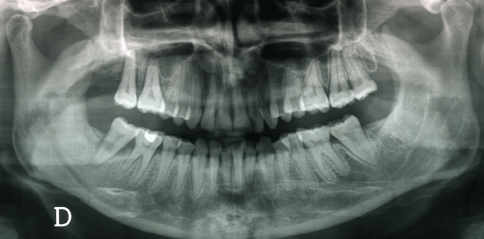

Fig. 3.

In this patient the panorex shows diffuse widening of the periodontal ligament space and osteosclerotic lamina dura

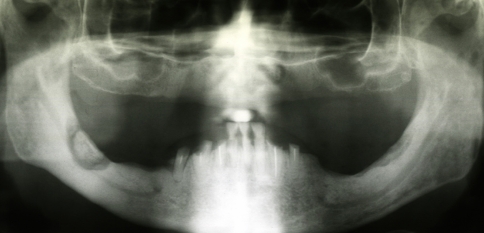

Fig. 4.

A panorex reveals the presence of areas of bone necrosis involving both sides of the mandible. Note the sequestrum in the right mandible. The patient had right lower lip paresthesia

Pathogenesis and Risk Factors

From what it is known to date it appears that the pathogenesis of BRONJ is due to a defect in jawbone physiologic remodeling and wound healing. The negative impact of bisphosphonates on bone physiology centers on osteoclast inhibition and apoptosis which result as a consequence of an irreversible block of the mevalonate pathway. The damaged osteoclast function affects the normal bone turnover and resorption process while additional negative effects of bisphosphonates also relate to depressed blood circulation in bones. In addition, bisphosphonates have the capability to inhibit endothelial cell function in vitro and in vivo and also demonstrate antiangiogenic properties because of their capacity to decrease circulating levels of the potent angiogenic factor VEGF, suppress endothelial cell proliferation and reduce the sprouting of new vessels [reviewed in 17–19, 21, 41, 42]. From the above considerations it appears that the pathogenesis of BRONJ reflects a multifactorial model, which also includes other additional factors such as genetic predisposition centered on polymorphism in drug or bone metabolism. On the base of the current knowledge, BRONJ seems to be an exclusive ailment of the jaw bones. Most cases of BRONJ develop in patients who have undergone tooth extraction or other forms of surgical procedures; however a certain number of both edentulous and dentate patients have developed necrotic bone spontaneously. This apparent and exclusive involvement of the jaw bones may be a mirror of the uniqueness of the oral environment. It is well known that in normal conditions healing of a wound of the jaw bones (e.g., extraction socket) occurs quickly and without complication. Instead, in patients who have received tumoricidal irradiation (and/or other toxic agents) the healing process and the vascular supply to the mandible and maxilla are compromised, then even minor injury or inflammatory/infective diseases in these sites increase risk for osteonecrosis and osteomyelitis. In relation to the negative effects of bisphosphonates, it is conceivable that, because the jaw bones are sites of high bone turnover, these drugs concentrate within the bone tissue. This may partially explain the selective preference of bisphosphonate osteonecrosis for the jaw bones [reviewed in 17–19, 21, 41, 42]. Reid and Bolland [43] recently discussed a novel pathogenetic hypothesis which considers the role of accumulated bisphosphonates in bone in concentrations sufficient to be directly toxic to the oral epithelium. This would result in the failure of healing of soft tissue lesions (such as those related to invasive dental procedures or by chronic trauma from dentures). In the opinion of the authors this model would explain why bone resection is not appropriate in managing BRONJ and suggests that drugs which reverse the effects of bisphosphonates in vitro might have a role in the management of this problem. Recent retrospective studies and review papers have identified and discussed several risk factors associated with BRONJ [6–8, 10–25, 42]. Major factors are a history of dental extractions, duration of bisphosphonate treatment, and the type of bisphosphonate. The majority of reported BRONJ cases are associated with recent dentoalveolar surgery. This fact underlines the relevant importance of optimal good health and avoiding extractions especially in cancer patients receiving nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates. However, lesions may also occur spontaneously in non-extraction sites such as dentate or non-dentate areas or in areas covered by prosthetic appliances. The phenomenon of spontaneous appearance of BRONJ may be explained by the fact that, once “metabolically damaged” by the treatment with bisphosphonates, the jaw bones remain susceptible even to minor causative factors such as prosthetic trauma [6, 11, 17]. The duration of bisphosphonate therapy is also an important factor which relates to the likelihood of developing BRONJ. In addition, the more potent nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates, such as pamidronate and zolendronate, are more often associated with the development of BRONJ than the oral bisphosphonate formulations [16–25]. An important paper published recently by Corso et al. [44] has highlighted the importance of reducing the schedule of zolendronic acid in order to lower the risk of BRONJ in patients with multiple myeloma. In particular, the authors recommended discontinuing bisphosphonate therapy after 2 years in patients achieving complete response or plateau phase. For patients still requiring treatment beyond 2 years, it was recommended to administer iv bisphosphonates every 3 months. This alternative schedule may represent a possible solution to significantly lower the risk of BRONJ while maintaining the efficacy of these drugs. A variety of etiological factors such as radiation and corticosteroid treatment, trauma, smoking, alcohol use, poor oral hygiene, herpes zoster, HIV infection and fungal infections and predisposing conditions such as diabetes, osteopetrosis, fibrous dysplasia, may also affect wound healing of the jaws bones and also must be considered as possible cofactors [10, 18, 42]. Of relevance is the finding that BRONJ patients show a high incidence (58%) of diabetes, where 14% would be expected in an age-matched population [45]. In summary, the fact that the majority of BRONJ cases are associated with the use of iv bisphosphonates for multiple myeloma and metastatic bone diseases suggests that dosage, length of treatment, and route of administration, as well as cofactors such as use of glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive agents, and dental surgery, could all be related to the incidence of this ailment. It should be stressed that the mechanisms involved in the development of BRONJ remain incompletely defined and further studies are necessary to understand the real impact of so many convergent factors.

Pathological Aspects

Diagnosis of BRONJ should be mainly based on clinical and radiographic criteria. Tissue biopsy is not always necessary and should be performed only if metastatic disease is suspected. At microscopic examination, the specimen shows areas of partially or completely necrotic bone and debris and fibrinous exudates accompanied by an inflammatory infiltrate formed by neutrophils, histiocytes, eosinophils and plasma cells (Fig. 5). The non-vital bone exhibits loss of osteocytes from the lacunae, peripheral resorption and bacterial colonization. Scattered sequestra and pockets of abscess formation are common. Specimens of superficial sequestrum almost always show necrotic bone surrounded by many bacterial colonies. Some of these are morphologically compatible with Actinomyces colonies. Special stains such as PAS and Gram staining can be useful to further confirm the findings. Several authors have found a striking high presence of Actinomyces in necrotic bone areas and considered these pathogens to be involved in the chronic, non-healing process of BRONJ [12, 19, 25, 31, 42]. It should be noted that Actinomyces are commonly present as commensals in the oral cavity thus their presence within the necrotic lesions is likely not an etiological factor in the pathogenesis of BRONJ, but rather a secondary infection of the necrotic tissues [31, 46].

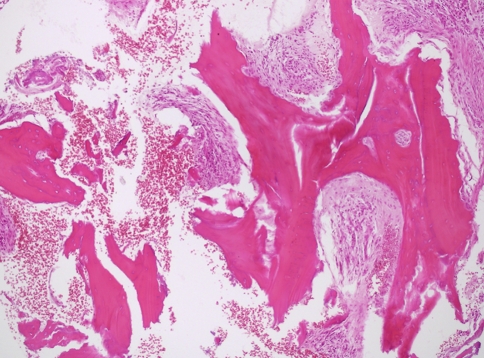

Fig. 5.

Photomicrograph of biopsy tissue showing irregular fragments of partially necrotic bone trabeculae, with empty lacunae or showing lacunae containing viable osteocytes. Note the bone resorption and the severe inflammatory infiltrate (H&E, 10× obj)

All the above features are similar to those observed in chronic osteomyelitis [10, 17–19, 47]. However, it remains a matter of debate whether the inflammatory process is the consequence of superinfection of preexisting dead bone or rather a secondary phenomenon caused by the microbial invasion of metabolically silent and poorly vascularized bone. The fact that bone tissue within or nearby the lesional area shows some degree of viability supports the hypothesis that the bone damage is initiated by injury and infection and is aggravated by the reduced remodeling capacity induced by bisphosphonates which ultimately compromises the reparative process. Histomorphologic analysis comparing BRONJ with osteoradionecrosis has revealed some important differences [48]. For example, specimens of BRONJ show multiple, partially confluent areas of necrotic bone in association with residual areas of vital bone whereas in osteoradionecrosis biopsies widespread homogeneous areas of complete bone necrosis are seen. Also no reduction of capillaries was seen in BRONJ and obliteration of blood vessels was only observed in a small number of BRONJ patients (13 versus 30% of radionecrosis cases). An increased cellularity was observed in both the intima and media of arteries in BRONJ lesions, but not in radionecrosis lesions. How these observations relate to the pathogenesis remains to be clarified. It has been suggested that bisphosphonates could induce bone changes similar to those that are found in osteopetrosis. Whyte et al. [49] have documented a case of acquired osteopetrosis in a 12-year-old boy who followed treatment with pamidronate. Genetic defects that abrogate the function of osteoclasts cause osteopetrosis, which is characterized by dense, poorly formed, and brittle skeletal tissue. Interestingly, patients affected by osteopetrosis may experience adverse events such as osteomyelitis of the jaw bones after tooth extraction that has similar clinical aspects and behavior as that observed in BRONJ patients.

Specific Laboratory Investigations

Microbial cultures (aerobic and anaerobic) may provide identification of pathogens causing secondary infection. Microbiological investigations have detected a variety of oral pathogens such as Actinomyces, Enterococcus, Candida albicans, Haemophilus influenza, alpha-haemolytic streptococci, Lactobacillus, Enterobacter and Klebsiella pneumoniae, etc. [25]. However, it is important to stress that cultures taken from an open sinus tract or exposed jaw bone may give misleading results because the isolates may include non-pathogenic microorganisms that are colonizing the site [50]. Monitor markers of bone turnover such as serum or urine N-telopeptide (NTx) and C-telopeptide (CTx) levels have been advocated as useful in predicting the future development of BRONJ. NTx and CTx are fragments of collagen that are released during bone remodeling and turnover [51, 52]. In particular, it has been suggested that serum CTx levels are reliable indicators of the risk of BRONJ development. These findings, however, are awaiting further confirmation and, in addition, a major limitation for their use is the fact that testing is available at only a few hospital centers.

Case Definition and Staging of BRONJ

In order to establish rational treatment guidelines and collect clinical information to assess the prognosis in patients with BRONJ, a working definition and staging system have been proposed by some researchers as well as associations such as the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS), the Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation and others [19, 24, 53]. To distinguish BRONJ from other delayed healing entities, the AAOMS [53] has adopted the following working definition. Patients may be considered to have BRONJ if the following three characteristics are present: (a) past or current therapy with bisphosphonates; (b) presence of exposed, necrotic bone in the maxillofacial region that has persisted for more than 8 weeks; and (c) absence of a history of radiation treatment to the jaw bones. The staging system reported here is the one which has been proposed by the AAOMS (Table 1) [53]. In stage 1 the disease is characterized by exposed bone and absence of symptoms. Patients at this stage usually do not require treatment. However, it is relevant to note that some patients my have pain prior to the appearance of radiographic or clinical signs of overt BRONJ. Patients in stage 2 show exposed bone with associated pain. This stage requires antimicrobial therapies, pain control and superficial debridement to relieve soft tissue irritation. Stage 3 is characterized by exposed bone associated with pain, adjacent or regional soft tissue swelling and signs of secondary infection resistant to antibiotic treatment. These patients, because of voluminous sequestra, often require surgical intervention to debride necrotic bone. In two recent articles, however, the above definition of BRONJ have been criticized because it appears too simplistic considering that differentiation between osteonecrosis complicated by infection and osteomyelitis with secondary osteonecrosis can be difficult, if not impossible. In addition, the role of other diagnostic procedures, such as biopsy, imaging and microbiology remains undefined [54, 55].

Table 1.

Clinical staging of BRONJ and treatment guidelinesa

| Stages | Treatments guidelines |

|---|---|

| At risk category: no apparent exposed/necrotic bone in patients treated with either oral or iv bisphosphonates | No treatment indicated |

| Patients education | |

| Stage 1: exposed/necrotic bone in patients who are asymptomatic and have no evidence of infection | Antibacterial mouth rinse |

| Clinical follow-up every 4 months | |

| Stage 2: exposed/necrotic bone associated with infection. Presence of pain and erythema in the lesional area with or without purulent drainage | Treatment with broad-spectrum oral antibioticsb |

| Antibacterial mouth rinse | |

| Pain control | |

| Superficial debridement to relieve soft tissue irritation | |

| Stage 3: exposed/necrotic bone in patients with infection and pain. Presence of one or more of the following: pathologic fractures, extraoral fistula, or osteolysis extending to the inferior border | Antibacterial mouth rinse |

| Antibiotic therapy and pain control | |

| Surgical debridement/resection for longer term palliation of infection and pain |

aModified from Ref. [53]

bPenicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium, metronidazole, cephalexin, clindamycin, fluoroquinolone

Management

Preventive Aspects

Until we have a better understanding of the role of bisphosphonates in the pathobiology of BRONJ it is pivotal that preventive measures be always taken in order to subvert the risk of developing this severe ailment. These include careful dental examination and mandatory extractions of candidate teeth with enough time allowed for healing in advance of the start of bisphosphonate treatment [9, 42, 56]. Based on previous experience with osteoradionecrosis, it is highly advisable that bisphosphonate therapy should be delayed until there is adequate bone healing [19, 56]. Of great importance is the adoption of preventive measures such as control of dental caries and periodontal disease, conservative restorative dentistry, avoiding dental implant placement, and the use of soft liners on dentures. This level of care must be continued indefinitely [10, 18, 19, 42]. In asymptomatic patients receiving iv Bisphosphonates, preventing dental diseases that may require dentoalveolar surgery is of great importance. In these patients any procedure that may cause direct osseous damage must be avoided, to include placement of dental implants. Non-restorable teeth should be treated by removal of the crown and endodontic treatment of the root remnants. One report [57] suggests the withdrawal of bisphosphonate treatment for 4–12 weeks before invasive dental surgery in order to allow restoration of osteclast function; however, considering the long half-life of bisphosphonates recovery of osteoclasts remains quite unrealistic. No scientific evidence is available so far to support this recommendation.

Patients receiving oral bisphosphonates have a much less risk of developing BRONJ than those treated with iv bisphosphonates. The risk of BRONJ, in patients taking oral bisphosphonates, may be associated with continuous therapy for more than 3 years. Other risk factors include diabetes, smoking, alcohol abuse, poor oral hygiene and corticosteroid therapy [56]. However it is important to stress that these points need further research and clarification. In general, patients taking oral bisphosphonates seem to have a less severe form of BRONJ and show a better response to stagespecific treatment strategies. In this group, dental extractions are not contraindicated. It is however recommended that patients should be adequately informed of the potential, although small, of the risk of defective bone healing. Although discontinuation of iv bisphosphonates in cancer patients has been recommended, stopping oral bisphosphonates prior to dental surgery cannot be universally endorsed at this time, since it is unknown whether this is effective in reducing the risk of BRONJ [41, 42, 56].

Treatment of Overt BRONJ

Currently, there are no effective treatments for BRONJ. A large variety of treatment modalities have been reported, including conservative medical management, various types of surgery, hyperbaric oxygen, ozone therapy and laser therapy. The current management guidelines are based mainly on expert opinions, because of the paucity of prospective, randomized clinical trials. The AAOMS has proposed a staging system in order to select the best treatment strategy for a given patient [53]. As it is delineated in Table 1, patients with stages 1 and 2 BRONJ should be treated using a conservative approach with the goal of preventing progression of lesions and limiting complications related to chronic infection. To achieve these goals, conservative debridement of bone sequestra, local irrigation with povidone–iodine and daily rinsing with 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash, antibiotic therapy and pain control should be considered [9, 16–18]. Surgical debridement has been variably effective in eradicating the necrotic bone. The goal of surgery should be to eliminate dead bone which acts as foreign material [56]; thus necrotic areas that are a constant source of soft tissue irritation should be removed or recontoured without exposure of additional bone. In patients with BRONJ it may be difficult to obtain a surgical margin with viable bleeding bone as the jaw bones are metabolically damaged by the bisphosphonates; therefore aggressive surgical treatment should be delayed if possible [56]. With this approach, 90% of patients are able to reach and maintain a pain free state compatible with a satisfactory quality of life [10, 56, 58]. It is notable that no specific guidelines were given regarding the use of anti-inflammatory or analgesic drugs, although these agents are important in alleviating the pain symptoms associated with BRONJ. Recent findings have further confirmed that non-surgical medical management of BRONJ, consisting in long-term administration of antibiotics, is very effective in controlling the progression of the disease [59]. In cases of stage 3 patients with pathologic mandibular fractures segmental resection and reconstruction are required. However, because of the potential failure of this surgical procedure the patient must be well informed of the carried risk. Also the immediate reconstruction with non-vascularized or vascularized bone may carry the risk of failure as necrotic bone can develop at the surgical site [56]. An alternative to the consideration that major surgery should be avoided, a recent paper has underlined the efficacy of marginal bone resection (limited to the alveolar bone) combined with autologous platelet-derived growth factor in treating 12 patients with BRONJ. Ten of the patients recovered with complete mucosal and bone healing [60].

The efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy remains uncertain. Some authors [6] have not considered it effective and, therefore, did not recommended it; other authors [7, 61], instead, have found hyperbaric oxygen therapy of some usefulness. A clinical trial is in progress in order to establish the efficacy of this treatment modality for patients with BRONJ [53]. Ozone therapy and laser therapy have also been employed following the rationale that they have some kind of antimicrobial, neoangiogenic and biostimulation properties [62, 63]; however the definitive therapeutic role of these treatment modalities remains to be determined. Although it may seem reasonable and prudent to suggest that stopping the administration of iv bisphosphonates would improve the resolution rate of BRONJ, there is no proof to support such an indication for management. In fact there is evidence from the published studies that drug withdrawal does not accelerate healing [17, 18, 42]. This can be well explained by the fact that bisphosphonates avidly bind to bone mineral around active osteoclasts, resulting in very high levels within resorption lacunae. Since bisphosphonates are not metabolized, high concentrations are maintained within the bone for a long period of time. In cancer patients with overt BRONJ, the cessation or interruption of bisphosphonates must be discussed with the oncologist and the patient and always weighted against the risk of skeletal complications and hypercalcemia of malignancy [10, 17, 19].

Conclusion

BRONJ has been observed in several oral medicine, maxillofacial and oncology departments around the world. Although the definitive role of bisphosphonates remains to be elucidated, the alteration in bone metabolism together with surgical insult or prosthetic trauma appears to be key factor in the development of osteonecrosis. Tooth extraction as a precipitating event is a common observation in the reported literature. The reported incidence of BRONJ is significantly higher with the iv preparations zoledronic acid and pamidronate while the risk appears to be minimal for patients receiving oral bisphosphonates. The significant benefits that bisphosphonates offer to patients clearly outbalance the risk of potential side effects; however, any patient for whom prolonged bisphosphonate therapy is indicated, should be provided with preventive dental care in order to minimize the risk of developing this severe condition. Although discontinuation of iv bisphosphonates in cancer patients has been suggested, cessation of bisphosphonates prior to dental surgery cannot be universally accepted at this time, since it is unknown whether this is effective in reducing the risk of BRONJ [64]. Studying populations longitudinally over many years will provide the answer to this question.

References

- 1.Wu S, Dahut WL, Gulley JL. The use of bisphosphonates in cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:581–91. doi: 10.1080/02841860701233435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J, Goodger NM, Pogrel MA. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with cancer chemotherapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1104–7. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg TJ, Ruggiero S. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:60. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00566-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1115–7. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Migliorati CA. Bisphosphonates and oral cavity avascular bone necrosis. New Engl J Med. 2003;21:4253–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruggiero SL, Mehrotra B, Rosenberg TJ, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates: a review of 63 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:527–34. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lugassy G, Shaham R, Nemets A, et al. Severe osteomyelitis of the jaw in long-term survivors of multiple myeloma: a new clinical entity. Am J Med. 2004;117:440–1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagan JV, Murillo J, Poveda R, et al. Avascular jaw osteonecrosis in association with cancer chemotherapy: series of 10 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:120–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vannucchi AM, Ficarra G, Antonioli E, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw associated with zoledronate therapy in a patient with multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2005;128:738. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ficarra G, Beninati F, Rubino I, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaws in periodontal patients with a history of bisphosphonates treatment. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:1123–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Migliorati CA, Schubert MM, Peterson DE, et al. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of mandibular and maxillary bone: an emerging oral complication of supportive cancer therapy. Cancer. 2005;104:83–93. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merigo E, Manfredi M, Meleti M, et al. Jaw bone necrosis without previous dental extractions associated with the use of bisphosphonates (pamidronate and zoledronate): a four- case report. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:613–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olson KB, Hellie CM, Pienta KJ. Osteonecrosis of jaw in patient with hormone-refractory prostate cancer treated with zoledronic acid. Urology. 2005;66:658. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zervas K, Verrou E, Teleioudis Z, et al. Incidence, risk factors and management of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with multiple myeloma: a single-centre experience in 303 patients. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:620–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanna G, Preda L, Bruschini R, et al. Bisphosphonates and jaw osteonecrosis in patients with advanced breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1512–6. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badros A, Weikel D, Salama A, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in multiple myeloma patients: clinical features and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:945–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woo S-B, Hellstein JW, Kalmar JR. Systematic review: bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:753–61. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Migliorati CA, Siegel MA, Elting LS. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis: a long-term complication of bisphosphonates treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:508–14. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruggiero SL, Fantasia J, Carlson E. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: background and guidelines for diagnosis, staging and management. Oral Surg Oral Pathol Oral Med. 2006;102:433–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bilezikian JP. Osteonecrosis of the jaw-Do bisphosphonates pose a risk? N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2278–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunstan CR, Felsenberg D, Seibel MJ. Therapy insight: the risk and benefits of bisphosphonates for the treatment of tumor-induced bone disease. Nature Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:42–55. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phal PM, Myall RW, Assael LA, et al. Imaging findings of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1139–45. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Body J-J, Coleman R, Clezardin P, et al. International society of geriatric oncology (SIOG) clinical practice recommendation for the use of bisphosphonates in elderly patients. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:852–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weitzman R, Sauter N, Eriksen EF, et al. Critical review: updated recommendations for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients-May 2006. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;62:148–52. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dannemann C, Gratz KW, Riener MO, et al. Jaw osteonecrosis related to bisphosphonates therapy. A severe secondary disorder. Bone. 2007;40:828–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farrugia MC, Summerlin DJ, Krowiak E, et al. Osteonecrosis of the mandible or maxilla associated with the use of new generation bisphosphonates. Laringoscope. 2006;116:115–20. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000187398.51857.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brooks JK, Gilson AJ, Sindler AG, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with use of risendronate: report of 2 new cases. Oral Sur Oral Med Oral Pathol. 2007;103:780–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nase JB, Suzuki JB. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and oral bisphosphonates treatment. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1115–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Senel FC, Tekin US, Durmus A, et al. Severe osteomyelitis of the mandible associated with the use of non-nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates (disodium clodronate): report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:562–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montazeri AH, Erskine JG, McQuaker IG. Oral sodium clodronate induced osteonecrosis of the jaw in a patient with myeloma. Eur J Haematol. 2007;79:69–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yarom N, Yahalom Y, Shoshani, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw induced by orally administered bisphosphonates: incidence, clinical features, predisposing factors and treatment outcome. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(10):1363–70. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0384-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barmias A, Kastritis E, Bamia C, et al. Ostenecrosis of the jaws in cancer after treatment bisphosphonates: incidence and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8580–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang EP, Kaban LB, Strewler GJ, et al. Incidence of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with multiple myeloma and breast or prostate cancer on intravenous bisphosphonate therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1328–31. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilkinson GS, Kuo Y-F, Freeman JL, et al. Intravenous bisphosphonate therapy and inflammatory conditions or surgery of the jaw: a population-based analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1016–24. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miles AE. Phosphorus necrosis of the jaw: “phossy jaw”. Br Dent J. 1972;133:203–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4802906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hellstein JW, Marek CL. Bisphosphonate osteochemonecrosis (bis-phossy jaw): is this phossy jaw of the 21st century? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:682–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong JK, Wood RE, McClean M. Conservative management of osteoradionecrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1997;84:16–21. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Epstein J, Meij E, McKenzie M, et al. Postradiation necrosis of the mandible: a long term follow-up study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1997;83:657–62. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz HC. Osteonecrosis of the jaws: a complication of cancer chemotherapy. Head Neck Surg. 1982;4:251–3. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890040313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Polizzotto MN, Cousins V, Schwarer AP. Bisphosphonate-associate osteonecrosis of the auditory canal. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silverman SL, Maricic M. Recent developments in bisphosphonates therapy. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;37(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hewitt C, Farah CS. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: a comprehensive review. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:319–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reid IR, Bolland MJ. Is bisphosphonates-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw caused by soft tissue toxicity? Bone. 2007;41:318–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.04.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corso A, Varettoni M, Zappasodi P, et al. A different schedule of zolendronic acid can reduce the risk of the osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2007;21:1545–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamaisi M, Regegev E, Yarom N, et al. Possible association between diabetes and bisphosphonates-related jaw osteonecrosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;92:1172–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tada A, Senpuku H, Motozawa Y, et al. Association between commensal bacteria and opportunistic pathogens in the dental plaque of elderly individuals. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:776–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bullough P. Osteonecrosis and bone infarction. In: Bullogh P, editor. Orthopaedic pathology. 4. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2004. pp. 347–62. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hansen T, Kunkel M, Weber A, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaws in patients treated with bisphosphonates-histomorphologic analysis in comparison with infected osteoradionecrosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2006;35:155–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whyte MP, Wenkert D, Clements KL, et al. Bisphosphonate-induced osteopetrosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:457–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa023110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. Lancet. 2004;364:269–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16727-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greenspan SL, Rosen HN, Parker RA. Early changes in serum N-telepeptide and C-telopeptide cross-linked collagen type 1 predict long-term response to alendronate therapy in elderly women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3537–40. doi: 10.1210/jc.85.10.3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schewelov T, Carlsson A, Dahlberg L. Cross-linked N-telopeptide of type I collagen (NTx) in urine as predictor of periprosthetic osteolysis. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:1342–8. doi: 10.1002/jor.20152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonates-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007;65:369–76 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Naveau A, Naveau B. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients taking bisphosphonates. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73:7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wyngaert T, Manon TU, Vermorken JB. Osteonecrosis of the jaw related to use of bisphosphonates. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19:315–22. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32819f820b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marx RE, Sawatari Y, Fortin M, et al. Bisphosphonates-induced exposed bone of the jaws: risk factors, recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1567–75. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thakkar SG, Isada C, Smith J, et al. Jaw complications associated with bisphosphonate use in patients with plasma cell dyscrasias. Med Oncol. 2006;23:51–6. doi: 10.1385/MO:23:1:51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pires FR, Mirando A, Cardoso ES, et al. Oral avascular bone necrosis associated with chemotherapy and bisphosphonate therapy. Oral Dis. 2005;11:365–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Montebugnoli L, Felicetti L, Gissi B, et al. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis can be controlled by nonsurgical management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 2007;104:473–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adornato MC, Morcos I, Rozanski J. The treatment of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws with bone resection and autologous platelet-derived growth factors. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:971–7. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Freiberger JJ, Padilla-Burgos R, Chhoeu AH, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment and bisphosphonates-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw: a case series. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1321–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Agrillo A, Petrucci MT, Tedaldi M, et al. New therapeutic protocol in the treatment of avascular necrosis of the jaws. J Cranio Surg. 2006;17:1080–3. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000249350.59096.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vescovi P, Merigo E, Meleti M, et al. Nd:YAG laser biostimulation of bisphosphonateassociated necrosis of the jawbone with and without surgical treatment. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007); (electronic version-in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Krueger CD, West PM, Sargent M, et al. Bisphosphonates-induced osteonecrosis of the jaws. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:276–84. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]