Abstract

Angiomatosis is a diffuse vascular lesion which involves a large segment of the body in a contiguous fashion involving multiple tissues (e.g. subcutis, muscle, bone, adipose tissue etc.) in different planes. Such lesions usually present in the first two decades of life with female predilection and are commonly seen in lower extremities. It clinically mimics hemangioma or vascular malformation and its surgical removal is difficult because of its infiltrative nature and thus has high recurrence rate (90%). Therefore a precise histopathological diagnosis of angiomatosis is important to achieve a curative resection. Histopathologically it consists of proliferating blood vessels of varying caliber, infiltrating into the soft tissues. Proliferating capillaries are seen within or adjacent to major vessels. Few cases are reported in head and neck region. This article highlights three unusual cases of angiomatosis reported as benign lesions, in rare sites such as the malar region (predominantly infiltrating the adipose tissue), within the masseter (predominantly infiltrating the muscle) and in the mandible (infiltrating the bone). Histopathological differential diagnosis is also discussed.

Keywords: Angiomatosis, Hemangioma, Infiltrative hemangioma

Introduction

Angiomatosis is a complex vascular malformation of infancy and childhood consisting of proliferating blood vessels with accompanying mature fat, fibrous tissue, lymphatics and nerves which may involve skin, subcutaneous tissue, skeletal muscle and occasionally bone [1]. It is extremely rare and benign but a clinically extensive vascular lesion of soft tissue which usually becomes symptomatic during childhood or adolescence [2].

According to Rao and Weiss [2], angiomatosis has been defined as a histologically benign vascular lesion that affects a large segment of the body in a contiguous fashion, either by vertically involving multiple tissue types (e.g. subcutis, muscle, bone) or by involving similar types of tissues (e.g. multiple muscle). It has a highly characteristic but not totally specific histologic pattern. It has no malignant potential, but because of its infiltrative nature, it could be misdiagnosed as a malignancy using imaging techniques. For these reasons diagnosis based on clinical and radiographic findings in correlation with histologic features would be desirable [3]. Its diffuse infiltrative nature makes surgical resection difficult; hence, recurrence is a common feature in angiomatosis [2, 3].

The aim of this paper is to present three cases of angiomatosis which were clinically mimicking hemangioma, lipoma and arteriovenous (AV) malformation at rare sites such as within the masseter, malar region and in the mandible, respectively. The histopathological differential diagnosis and prognostic importance of angiomatosis is also discussed.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 13-year-old female presented with the complaint of swelling in the right side of face since 2 years. The swelling had slowly progressed in size during the period.

On examination, a diffuse swelling in the right side of the face extending from the ala-tragal plane superiorly to the lower border of mandible, from the anterior to posterior border of masseter, was seen. Skin overlying the swelling was normal in color and texture.

Intraorally, bluish discolouration of the right buccal mucosa with telengiectasia or spider nevi appearance was evident (Fig. 1a). On palpation the swelling was non tender, collapsible on digital pressure and filled up on releasing the pressure. The submandibular lymph nodes were palpable bilaterally.

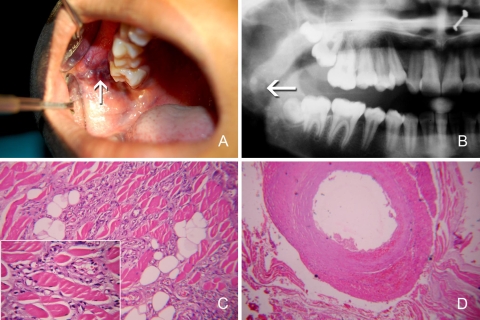

Fig. 1.

a Lesion seen on buccal mucosa, b small opacities depicting phleboliths, c proliferating vessels infiltrating in between the muscle bundles, d dilated thick walled vessel between the muscle bundles

The orthopantamogram (OPG) showed calcified scattered masses lateral to the right ramus of the mandible (Fig. 1b). Ultrasonography revealed the presence of hypoechoic areas showing the distorted fibers of the masseter muscle and hyperechoic areas showing phleboliths. Thus a provisional diagnosis of hemangioma was considered.

Excision was done under general anesthesia and operative findings presented the buccal pad of fat infiltrated with vascular tissues and involving the right masseter muscle. Gross specimen showed soft tissues which were black in color with a few calcified masses (possibly phleboliths).

The microscopic findings revealed disorganized proliferation and randomly arranged blood vessels of varying sizes in between muscle bundles; endothelial proliferation and canalization was also seen (Fig. 1c, d). An extensive area of hemorrhage was evident and so were calcification depicting phleboliths. Based on clinical, radiological and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of angiomatosis was derived.

Case 2

A 19-year-old female presented with a chief complaint of swelling in left side of the face since 3–4 years. On examination, a well circumscribed solitary swelling of the left malar region was seen which measured approximately 3 × 3 cm2 (Fig. 2a). The overlying skin was normal, soft and non-tender on palpation. Radiographically, no significant findings were seen and a provisional diagnosis of lipoma was considered.

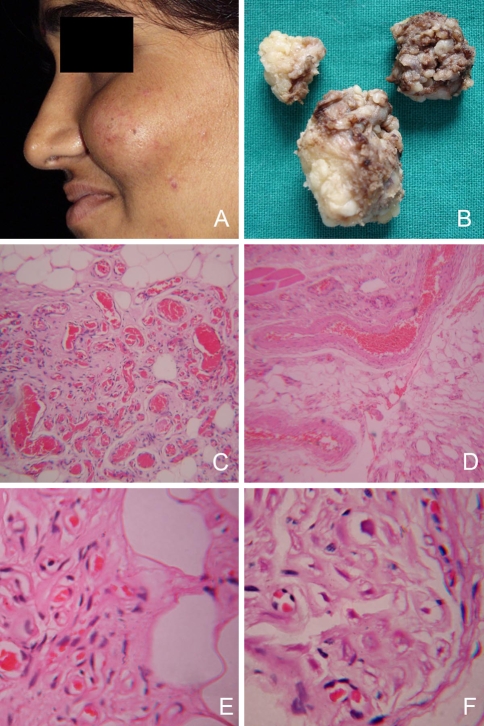

Fig. 2.

a Circumscribed swelling on left malar region, b gross specimen with nodular surface and irregular borders, c blood vessels of varying caliber, infiltrating into the stroma rich in adipose tissue, d proliferating capillaries around feeder vessel, e canalization and new blood vessel formation, f nerve bundle infiltrated by proliferating capillaries

Excision was done under general anesthesia. Gross specimen showed soft tissue mass floating in formalin, with irregular borders and white to brownish in color (Fig. 2b).

Microscopically the excised specimen revealed blood vessels of varying caliber infiltrating into to the stroma rich in adipose tissue (Fig. 2c). Few areas showed small proliferating capillaries adjacent to major feeder vessels (Fig. 2d) and areas of canalization and new blood vessel formation were also evident (Fig. 2e). Nerve bundles too, were infiltrated by proliferating blood vessels (Fig. 2f), prompting a final diagnosis of angiomatosis.

Case 3

A 16-year-old male presented with the chief complaint of swelling on lower right region of the jaw since 2 months. The swelling had gradually progressed in size and produced mild pain on mastication. The lesion presented with facial asymmetry at the lower third of the face, with bony hard swelling extending from the symphysis to angle of the mandible (Fig. 3a). The swelling was tender on palpation. Intraoral examination revealed diffuse bony swelling extending from the mandibular right central incisor to second molar and presented with egg shell crackling. All teeth associated with the lesion were mobile.

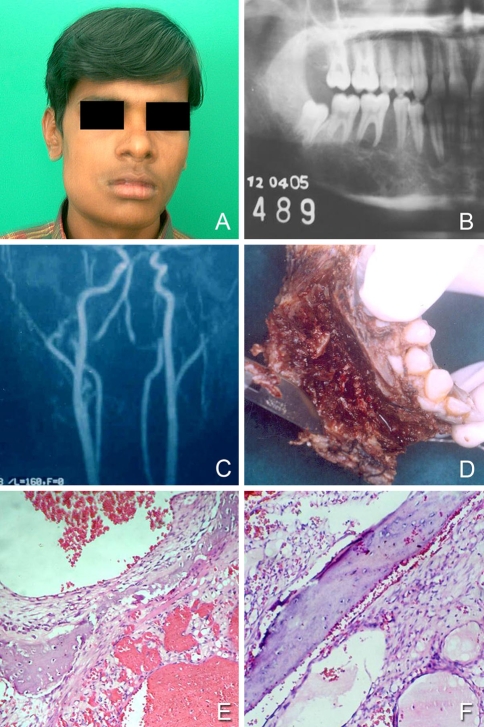

Fig. 3.

a Large diffuse swelling on the right side of the mandible, b panoramic radiograph showing large ill-defined radiolucency extending from 41 to 47, c angiography showing mild increase in vascularity of right external carotid artery, d gross specimen showing large vascular channels inside the body of the mandible, e vascular channels infiltrating into the bone, f periosteal infiltration

OPG revealed radiolucency extending from mandibular right central incisor to second molar (Fig. 3b). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) hard tissue window showed lytic lesion in the medulla of the mandible, with erosion of buccal and lingual cortical plates, thus giving a sun-ray appearance (reactive periostitis). Angiography presented with mild increase in vascularity of the right external carotid artery (Fig. 3c). A provisional diagnosis of AV malformation was considered.

Hemimandibulectomy and reconstruction with free iliac crest bone was done. The gross specimen showed areas of dark brown to bluish lesion on both medial and lateral aspect of the mandible. On opening, large vascular channels were seen (Fig. 3d).

Histopathological findings revealed numerous vascular channels of capillary and cavernous caliber infiltrating into the bone (Fig. 3e). Areas of periosteal infiltration with reactive new bone formation were also evident (Fig. 3f) and a histopathological diagnosis of angiomatosis was confirmed.

Discussion

Diffuse form of hemangioma can be described as angiomatosis. It clinically mimics hemangioma or AV malformation [4]. It is also termed as diffuse hemangioma, haemangiomatosis [5] and infiltrative hemangioma [6]. The co-existence of vascular proliferation and abundant fat in this infiltrating lesion previously inspired the now obsolete term ‘infiltrative angiolipoma’ [3]. If only muscles are predominantly involved, it may also be termed as ‘Intra-muscular hemangioma’, which is once again a subjective diagnosis [7].

Arteriovenous malformation, a term well founded in the radiologic literature, implies functional arteriovenous communications and may correspond in some instances to what pathologists term angiomatosis [2]. Because of nomenclature issues, it has been very difficult to gain a clear understanding of this lesion and in particular to compare the experience derived from one speciality to another [2].

To promote a more standardized approach to diagnosis, Rao and Weiss [2] have suggested that the term ‘angiomatosis’ be used to connote a histologically benign vascular lesion that extensively involves a region of the body or several different tissue types in a contiguous fashion.

Angiomatosis can either be congenital or acquired. The congenital form may be seen sporadically or accompanying certain types of syndromes such as Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome, Sneddon’s syndrome, or Gorham disease [8]. The acquired form of angiomatosis may be infectious or iatrogenic. Bartonellosis and HIV are associated with angiomatosis. Iatrogenic cases occur after AV fistula formation or trauma [8].

Rao and Weiss’s study [2] bears similarities to our reports in that the lesions commonly occurs in the second decade of life, there is a female predilection to its occurrence and it presents as a diffuse persistent swelling having two histological patterns. These lesions probably begin during early intra-uterine life, grow proportionately with the fetus and consequently affect large areas of the body [2, 4].

Histopathologically, two types of patterns are seen. The most common pattern consists of a haphazard proliferation of varying sized vessels, particularly large veins. However, the most distinctive feature is the clusters of capillary vessels residing within or adjacent to the vein walls. A second but uncommon pattern is the clusters of capillary-sized vessels arranged in nodules around a large vessel in the center. Both types are typically associated with large amounts of adipose tissue and hence these lesions have lead previous authors to use the term ‘infiltrating angiolipoma’, suggesting that these are more generalized mesenchymal proliferations rather than exclusive vascular pathology [8]. Similar histopathologic features are seen in the present case reports.

Because of its infiltrative nature, angiomatosis may resemble many of the vascular tumors and malformations. Histopathological differential diagnosis includes angiolipoma, angiomyolipoma, infiltrating lipoma, angiomyxolipoma and liposarcoma [6].

Angiolipoma can be considered as an important differential diagnosis, but it is well circumscribed and proliferating vessels are usually concentrated at the periphery of intratumoral lobules of adipocytes [6]. Angiomyolipoma can be distinguished from angiomatosis as they are composed of varying amounts of blood vessels, smooth muscle and fat [9]. Infiltrating lipoma consist of lesional fat tissue infiltrating in the form of long thin streaks radiating from the intratumoral mass [6]. Angiomyxolipoma usually resembles angiomatosis due to presence of adipose tissue component and blood vessels with thick and thin walls. It can be distinguished by the presence of myxoid change in adipose tissue and absence of haphazard blood vessel proliferation [10]. Liposarcoma can also be considered as a differential diagnosis; however, mitotic figures, cellular atypia and lipoblasts (signet ring appearance) are not seen in angiomatosis.

The treatment of choice in extensive angiomatosis is either radiotherapy or Interferon α-2a treatment [11]. In localized cases, complete resection is preferred but there is a risk of local recurrence. Angiomatosis has no tendency to progress or evolve histologically to a more aggressive lesion. On follow up, nearly 90% of patients experienced local recurrence and approximately 40% encountered more than one local recurrence within a period of 5 years [2].

Conclusion

Angiomatosis is rare in the head and neck region. Its diffuse infiltrating nature may give a false malignant picture. Histopathological diagnosis of angiomatosis is important due to its high recurrence rate. The possibility of angiomatosis should be considered whenever a persistent swelling in the head and neck region in early childhood is seen. Precise diagnosis is vital to achieve a curative resection.

References

- 1.Howat AJ, Campbell DE. Angiomatosis: a vascular malformation of infancy and childhood—report of 17 cases. Pathology. 1987;19(4):377–382. doi: 10.3109/00313028709103887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao VK, Weiss SW. Angiomatosis of soft tissue—an analysis of the histologic features and clinical outcome in 51 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16(8):764–771. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radin DR. Angiomatosis of the abdominal wall: imaging findings in three adults. Radiology. 1994;193:543–545. doi: 10.1148/radiology.193.2.7972776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and Weiss. Soft tissue tumors. 5. Philadelphia: Mosby Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RC, editors. Oral pathology. 5. Philadelphia: Saunders Company; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouquot JE, Nikai H. Lesions of the oral cavity. In: Gnepp DR, editor. Diagnostic surgical pathology of the head and neck. 1st ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 2001.

- 7.Sunil TM. Intramuscular hemangioma complicated by a Volkmann’s like contracture of the forearm muscles. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:270–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirma C, Izgi A, Yakut C, et al. Primary left ventricular angiomatosis. Int Heart J. 2006;47:469–474. doi: 10.1536/ihj.47.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner BJ, Wong-You-Cheong JJ, Davis CJ Jr. Adult renal hamartomas. Arch AFIP-Radiographics. 1997;17:155–69. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Mai KT, Yazdi HM, et al. Angiomyxolipoma of spermatic cord. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20(9):1145–1148. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199609000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Val-Bernal JF, Martino M, Graces CS, et al. Soft tissue angiomatosis in adulthood. Pathol Int. 2007;55:155–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2005.01801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]