Abstract

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the larynx is extremely rare in adolescents and typically has an aggressive nature. The mechanism of laryngeal oncogenesis is complex and little is known about the role that human papillomavirus (HPV) plays in SCC in adolescents. We report a case of invasive laryngeal SCC that co-expressed HPV DNA subtypes 16 and 18 in a 13 year-old boy. Detection of HPV DNA types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, and 51 was performed by in situ hybridization, with confirmation by polymerase chain reaction. Immunohistochemical staining with p16 and HPV 16/18 revealed diffusely positive staining in the tumor cells. Coinfection by HPV DNA types 16 and 18 has not been previously reported, but our case suggests that HPV is a risk factor in developing laryngeal SCC in children and adolescents. Future studies evaluating HPV in the pathogenesis of these lesions is recommended to determine its prognostic significance.

Keywords: Laryngeal carcinoma in adolescents, Vocal cord, Hoarseness, Squamous cell carcinoma, Human papillomavirus (HPV), P16, Translocation (15;19)

Introduction

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the larynx is more common in adults than adolescents and is essentially a lifestyle-related cancer occurring after decades of tobacco use. The literature contains fewer than 75 cases of SCC in the pediatric population to date, therefore, the treatment and prognosis of laryngeal SCC is not well-defined. Recently, studies have suggested that prognosis may be affected by the presence of chromosomal translocation (15;19) or of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA [1–8]. In this case report, we present a 13 year-old boy with invasive SCC in his right vocal cord. Immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization (ISH) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were performed to identify possible expression of p16 and infection with HPV DNA. Dual-color fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assays were utilized to detect translocation (15;19).

Report of a Case

A 13 year-old boy presented to an otolaryngologist for evaluation of prolonged hoarseness, which was unassociated with dysphasia or odynophagia. He and his mother reported the presence of symptoms for approximately 1 year, but had given no serious thought to their origin given his pubertal age and participation in strenuous vocal activities as a school mascot. He reported no previous history of laryngeal papillomatosis, laryngeal surgery, trauma, intubation, radiation, alcohol or tobacco use, major medical illness, or sexual activity. There was no reported history of laryngeal cancer or papillomatosis in his siblings, and no abnormal pap smear results or cervical lesions in his mother.

Upon initial office evaluation, the patient was notably dysphonic. Oral examination revealed no visible or palpable lesions of the floor of mouth, buccal mucosa, base of the tongue, palate, or tonsillar fossae. On flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopic examination, there were no abnormalities within the nasopharynx, oropharynx, or hypopharynx. Laryngeal evaluation, however, revealed an erythematous, bulky lesion involving the entire length of the right true vocal cord. Given these findings, the patient was scheduled for a direct laryngoscopy and biopsy of the lesion in the operating room with a presumed diagnosis of laryngeal papilloma.

On further evaluation by direct laryngoscopy, the lesion was found to be firmly attached to the right true vocal cord although the right true vocal cord was freely mobile. The right ventricle was obliterated due to its mass effect. The lesion extended to the vocal process posteriorly, and near to the anterior commissure anteriorly. Multiple biopsies were obtained from the right vocal cord for histologic diagnosis.

Materials and Methods

The hematoxylin–eosin stained slide prepared from a formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue block was reviewed by two board certified pathologists. Immunohistochemical staining for p16 (p16INK4a kit; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and HPV types 6/11, 16/18, 31/33/51 (Zymo Research, Orange, CA) were performed with appropriately reacting positive and negative controls. In situ hybridization (ISH) was used to detect HPV DNA types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, and 51, and confirmed by classical polymerase chain reaction (PCR). PCR was performed with a platinum tag polymerase and a set of degenerate primers (HPV-MY09, HPV-MY11, HPV-GP5, and HPV-GP6) capable of binding DNAs of 23 mucosotrophic HPVs, including HPV-6, 11, 16, and 18. Touchdown PCR was performed simultaneously and compared with the results obtained by the classical PCR method. For quality control, beta-globin was amplified separately using a set of specific primers to ensure the presence of sufficient DNA for each PCR reaction. Dual-color FISH assays were performed to evaluate chromosome 19p13.1 BRD4 and 15q13 NUT break points for the presence of t(15;19) as previously described [5].

Results

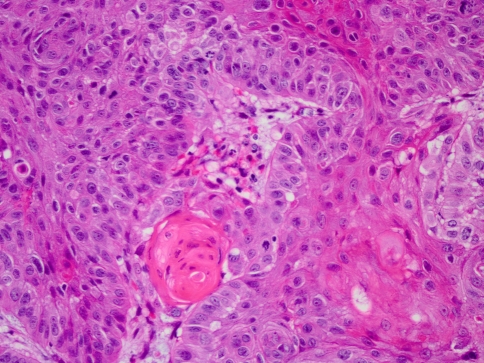

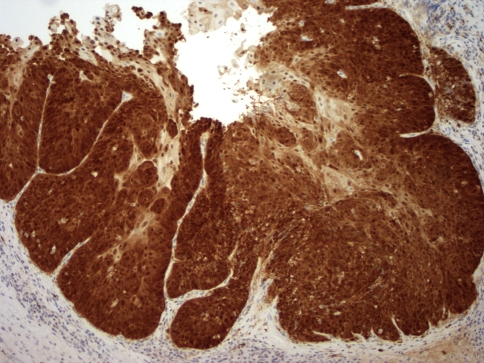

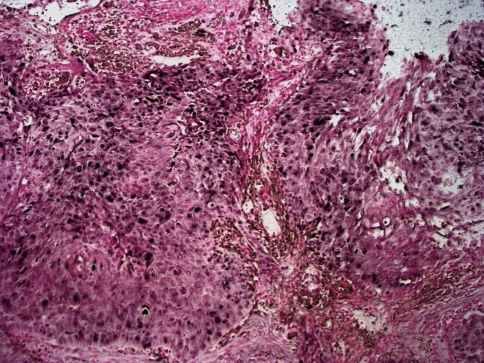

The right true vocal cord biopsy demonstrated in situ and invasive moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 1). It was concluded that the patient had a T2N0Mx, stage II squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx. Immunohistochemical staining for p16 showed strong and diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in the tumor (Fig. 2). Immunohistochemical staining for HPV 16/18 showed strong nuclear staining in numerous cells (Fig. 3). ISH demonstrated co-expression of HPV DNA subtypes 16 and 18, which was confirmed by PCR. Dual-colored FISH assays failed to reveal translocation (15;19). After a multidisciplinary evaluation of the case, including radiation oncology, medical oncology, and otolaryngology, the decision was made to pursue radiation therapy to the true vocal cords only, without chemotherapy or surgical resection. The patient received hyperfractionated therapy for 49 days with a total dose of 8160 cGy delivered.

Fig. 1.

Histologic section of the right true vocal cord biopsy displays squamous cell carcinoma (H & E 40×)

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical staining with p16 shows strong diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in squamous cell carcinoma (10×)

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical staining with anti-papillomavirus antibody 16/18 reveals strong nuclear staining in numerous cells (10×)

Discussion

Squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx is extremely rare in adolescents and children, and fewer than 75 cases have been reported in the literature to date. Clinical manifestations of laryngeal carcinoma in adolescents may include hoarseness or cough, which may be mistaken for common respiratory infections, prepubertal voice change, or other benign childhood conditions [9]. On laryngeal exam a polyp or mass may be discovered, making juvenile papillomatosis the presumed diagnosis. Due to its rarity, tendency to mimic benign conditions, and the relative difficulty of the pediatric laryngeal examination, SCC is not usually considered in the differential diagnosis of persistent hoarseness or cough, which may lead to a delay in diagnosis.

Vocal folds are the most common site of involvement by SCC in adolescents, followed by supraglottic and then subglottic locations [9, 10]. In adolescents, 60% of cases affect boys, compared to adults, in whom 80% of patients are men [10, 11]. Additionally, cases increase in frequency as patients increase in age [10, 11]. The major risk factor for SCC in adolescents is prior radiation for juvenile papillomatosis, in contrast to adults, in whom smoking is the predominant etiological factor [9]. Other risk factors include second-hand smoke, asbestos exposure, and a family history of malignant tumors [12].

On biopsy, laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma in adolescents closely parallels the squamous histology seen in adult patients, although its behavior has been thought to be more aggressive than that found in adults [11]. Laryngeal carcinoma in adolescents has been reported to mirror that of adults in regard to pattern of local spread [10].

The management of laryngeal malignancy in children is more difficult than in adults because the tumors tend to behave more aggressively, likely due to their delayed diagnosis [13]. Additionally, pediatric anatomic structures are delicate, and there may be long-term complications following treatment, including psychosocial factors specific to adolescents [13]. Treatment protocols have not been well-established due to the scarcity of cases, but it is typically based upon the stage of the tumor, laryngeal cartilage involvement, and metastases [13]. SCC in children tends to respond to treatment in a way similar to that of SCC in adults [10, 11]. Surgical resection may be difficult in some cases due to the desire to preserve laryngeal function and voice. Initial management may combine surgery, radiotherapy, and possibly chemotherapy.

In our case, the multidisciplinary team chose to treat the patient with hyperfractionated radiation therapy only, with a total dose of 8160 cGy delivered. After 1 year of follow-up, our patient is doing well and had complete eradication of his SCC without recurrence. However, long-term follow-up will be important for our patient, as well as other patients, who are at an increased risk for radiation-induced endocrinologic deficiencies, arrested growth of irradiated tissues, and for the development of second malignancies.

The prognosis of laryngeal carcinoma in adolescents is unclear because survival rates have not been reported according to tumor stage due to the scarcity of cases [14]. Recently, studies have suggested that prognosis may be affected by the presence of chromosomal translocation (15;19) or the presence of HPV DNA within the tumor cells. Translocation (15;19) results in a BRD4-NUT fusion oncogene, which likely disrupts the normal BRD4 function of regulation of cell cycle progression [6]. Translocation (15;19) has been described as part of a distinct clinicopathologic entity characterized by young age, female predilection, midline carcinoma of the neck or upper thorax, and a rapidly fatal course [1]. The limited literature on translocation (15;19) carcinoma suggests that this entity arises from thymic or respiratory epithelium and is very unresponsive to aggressive chemoradiotherapy and is commonly lethal [5]. Rahbar et al. reported in [2] the presence of translocation (15;19) in carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract in children indicates a poor prognosis despite aggressive multi-modality treatment . The two children in this study with translocation (15;19) both died of their disease with a mean survival of 6 months, compared to the five children without translocation (15;19) who were disease free at a mean follow-up of 47 months. French et al. [5] found in 2004 that of 11 patients with translocation (15;19), 43% had poorly differentiated carcinomas and 47% arose within the respiratory tract . Our case was evaluated by dual-color FISH assays and found to be negative for translocation (15;19).

It has been well-established that low risk HPV DNA is an etiological factor in the development of laryngeal papillomas. Major et al. [15] found that low risk HPV-6 and HPV-11 DNA were present in 100% of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis cases. Additionally, HPV-11 was found in all laryngeal and bronchogenic cancers in patients with a history of early onset RRP [16]. Many cancers of the head and neck have also been reported to express HPV DNA, however, the results of the studies are quite variable, possibly due to the small number of cases, the different HPV DNA detection methods used, or the limited number of DNA subtypes included in the detection method. The literature reveals the broad heterogeneity in the results of these studies with a wide range of reported HPV positivity in head and neck cancers and, more specifically, laryngeal carcinoma.

On average, most studies investigating HPV in head in neck SCC reflect a HPV positivity rate close to 35%. In 2005, a meta-analysis of 5046 head and neck SCC specimens from 60 studies found an overall HPV positivity of 25.9% [17]. Gallegos-Hernandez et al. found HPV positivity in 42% (118 patients) of head and neck SCC, while Badaracco et al. identified HPV in 18.3% of 115 patients with head and neck SCC [7, 18]. A report published in [19], studied 253 cases of oropharyngeal carcinoma and identified HPV DNA in 25% of the samples. Syrangen et al. [3] found tonsillar carcinomas to have a higher prevalence of HPV at 51%, compared to 22% of oral carcinomas and sinonasal carcinomas.

With regard to SCC of the larynx, the frequency of HPV positivity is quite variable. A meta-analysis in 2005 included 1435 cases of laryngeal cancer, which demonstrated HPV DNA positivity in 24% [17]. In [20], it was reported that HPV DNA was detected in 37.3% of the 110 cases of laryngeal carcinoma that were studied by de Oliveria et al. Gallegos-Hernandez et al. found HPV positivity in 50% of laryngeal cancer patients, whereas the HPV prevalence was 13% in a study of 91 laryngeal carcinomas by Gorgoulis et al. [18, 21].

Many studies have investigated the frequency with which the most common North American HPV subtypes are present in head and neck SCC. Most reports are in agreement that HPV-16 is the most frequently isolated subtype. Gallegos-Hernandez et al. [18] reported HPV-16 in 68.7% of 118 HPV-positive cases of head and neck SCC. Badaracco et al. [7] also found HPV-16 to be the most frequent subtype in 67% of 21 HPV-positive cases of head and neck SCC, followed by HPV-6, HPV-33, HPV-35, and HPV-58. HPV-16 was reported in 90% of the HPV-positive oropharyngeal carcinomas by Gillison et al. [19]. In 2005, Syrangen found HPV-16 in 84% of tonsillar tumors [3]. Balukova et al. studied 48 patients with laryngeal cancer and detected HPV-18 in 13%, while Gorgoulis et al. found HPV-16 to be present in 63% of 19 cases of laryngeal carcinoma [21, 22].

In our case report, the tumor was strongly positive for p16, as well as for the expression of HPV DNA types 16 and 18 by immunohistochemistry, ISH and PCR. In 1994, a 12 year-old boy had laryngeal SCC that co-expressed HPV DNA types 18 and 33 [23]. The boy had no other risk factors for SCC and the authors concluded that coinfection by two HPV types might substitute for carcinogenic cofactors normally present in adult laryngeal carcinomas. In 2006, two cases of laryngeal cancer were found to contain both high-risk and low-risk HPV by Manjarrez et al., [24] suggesting that both low-risk and high-risk HPV might be involved in the development of laryngeal malignant tumors, and that these viruses may be a synergistic risk factor for malignant development. Gorgoulis et al. [21] found HPV co-expression in 3 of 19 HPV-positive cases with HPV types 6/33, 16/33, and 6/18. Given that HPV can be identified in up to 25% of normal laryngeal mucosa samples, it could also be hypothesized that the low-risk infection may only be incidental and that the carcinogenic effect is a solitary effort by the high-risk HPV subtype [21, 25].

Although many studies have investigated the presence of HPV in head and neck cancers, only a few have correlated its prognostic significance. It has been reported that HPV-positive cancers of the head and neck, including the tonsil, oropharynx and oral cavity have a better overall survival than HPV-negative cancers [3, 4, 7, 8]. Two studies found that male gender contributed to a greater prognosis in patients with HPV-positive cancers [3, 4].

Cancers commonly contain alterations involving the p16 gene. The p16(INK4a) protein inhibits cyclin-dependent kinases and acts as a tumor suppressor to negatively regulate the cell cycle [26]. Evidence suggests that overexpression of the p16(INK4a) protein indicates infection with and genomic integration of high-risk HPV [27]. Additionally, it and predicts progression to cervical high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSILs) and carcinoma due to HPV-induced cell cycle dysregulation [27]. Therefore, p16 immunostaining of tumor nuclei and cytoplasm may serve as a marker for HPV positivity of the tumor.

Because the p16 protein is an important cell cycle regulatory protein, underexpression of this protein will allow cancer cells to proliferate without control. In HPV-negative lesions, downregulation of p16 has been correlated with increased dedifferentiation, more locally advanced stage, and tendency for radiotherapy failure in laryngeal SCC [28, 29]. Yuen et al. [29] found decreased p16 expression in 48% of the 225 head and neck squamous cell carcinomas studied in 2002. Additionally, the same study reported tumors of the larynx to have a significantly higher frequency of weak p16 expression compared with tumors of the oral cavity and pharynx.

As evidenced by our case report, laryngeal SCC in adolescents may present with nonspecific symptoms that mimic benign childhood conditions and lead to a delayed diagnosis. Early recognition and diagnosis is of therapeutic importance because of its aggressive nature, potential for associated complications and frequently poor outcome. This case report demonstrates that HPV can be positive in laryngeal SCC in adolescents, therefore, HPV testing should be considered for all laryngeal SCC in adolescents since it has both prognostic and potentially therapeutic implications. In addition, given this HPV expression, vaccination may be considered and requires further investigation.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Vargas SO, French CA, Faul PN, et al. Upper respiratory tract carcinoma with chromosomal translocation 15;19: evidence for a distinct disease entity of young patients with a rapidly fatal course. Cancer. 2001;92(5):1195–203. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010901)92:5<1195::AID-CNCR1438>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahbar R, Vargas SO, Miyamoto CR, et al. The role of chromosomal translocation (15;19) in the carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(6):698–704. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(03)01451-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Syrjänen S. Human papillomavirus (HPV) in head and neck cancer. J Clin Virol. 2005;32(Suppl 1):S59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ritchie JM, Smith EM, Summersgill KF, et al. Human papillomavirus infection as a prognostic factor in carcinomas of the oral cavity and oropharynx. Int J Cancer. 2003;104(3):336–44. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.French C, Kutok J, Faquin W, et al. Midline carcinoma of children and young adults with NUT rearrangement. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4135–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.French C, Miyoshi I, Kubonishi I, et al. BRDR4-NUT fusion oncogene: a novel mechanism in aggressive carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63(2):304–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Badaracco G, Rizzo C, Mafera B, et al. Molecular analyses and prognostic relevance of HPV in head and neck tumours. Oncol Rep. 2007;17(4):931–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fakhry C, Westra W, Sigui L, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus—positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:261–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDermott A, Raj P, Glaholm J, et al. De novo laryngeal carcinoma in childhood. J Laryngol Otol. 2000;114(4):293–5. doi: 10.1258/0022215001905382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gindhart TD, Johnston WH, Chism SE, et al. Carcinoma of the larynx in childhood. Cancer. 1980;46(7):1683–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19801001)46:7<1683::AID-CNCR2820460730>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zalzal GH, Cotton RT, Bove K. Carcinoma of the larynx in a child. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1987;13(2):219–25. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(87)90099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rastogi M, Srivastava M, Bhatt MLB, et al. Laryngeal carcinoma in a 13 year-old child. Oral Oncol Extra. 2005;41:207–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ooe.2005.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prasad KC, Abraham P, Peter R. Malignancy of the larynx in a child. Ear Nose Throat J. 2001;80(8):508–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laurian N, Sadov R, Strauss M, et al. Laryngeal carcinoma in childhood. Report of a case and review of the literature. Laryngoscope. 1984;94(5):684–7. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198405000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Major T, Szarka K, Sziklai I, et al. The characteristics of human papillomavirus DNA in head and neck cancers and papillomas. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(1):51–5. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.016634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reidy PM, Dedo HH, Rabah R, et al. Integration of human papillomavirus type 11 in recurrent respiratory papilloma-associated cancer. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(11):1906–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000147918.81733.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreimer A, Clifford G, Boyle P, et al. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:467–75. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallegos-Hernandez J, Paredes-Hernandez E, Flores-Diaz R, et al. Human papillomavirus: association with head and neck cancer. Cir Cir. 2007;75(3):151–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillison M, Koch W, Capone R, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:709–20. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Oliveira D, Bacchi M, Macarenco R, et al. Human papillomavirus and Epstein-Barr virus infection, p53 expression, and cellular proliferation in laryngeal carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;126:284–93. doi: 10.1309/UU2JADUEHDWATVM9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gorgoulis V, Zacharatos P, Kotsinas A, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) is possibly involved in laryngeal but not in lung carcinogenesis. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:274–83. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(99)90005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balukova O, Shcherbak L, Savelov N, et al. Papilloma virus infection in pretumor and tumor masses of the larynx. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 2004;(12):36–9. [PubMed]

- 23.Simon M, Kahn T, Schneider A, et al. Laryngeal carcinoma in a 12 year-old child. Association with human papillomavirus 18 and 33. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;120(3):277–82. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1994.01880270025005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manjarrez M, Ocadiz R, Valle L, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus and relevant tumor suppressors and oncoproteins in laryngeal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(23):6946–51. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aaltonen L, Rihkanen H, Vaheri A. Human papillomavirus in larynx. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:700–7. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200204000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pietruszewska W, Rieske P, Murlewska A, et al. Expression of p16 and protein in the evaluation of dynamics of laryngeal cancer growth. Otolaryngol Pol. 2004;58(1):173–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holladay E, Logan S, Arnold J, et al. A comparison of the clinical utility of p16(INK4a) immunolocalization with the presence of human papillomavirus by hybrid capture 2 for the detection of cervical dysplasia/neoplasia. Cancer. 2006;108(6):451–61. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krecicki T, Smigiel R, Fraczek M, et al. Studies of the cell cycle regulatory proteins p16, cyclin D1 and retinoblastoma protein in laryngeal carcinoma tissue. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118(9):676–80. doi: 10.1258/0022215042244769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuen P, Man M, Yin Lam K, et al. Clinicopathological significance of p16 gene expression in the surgical treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:58–60. doi: 10.1136/mp.55.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]