History

A 14-month-old male presented with spontaneous left ear bleeding. The lesion was clinically thought to be, and was treated as, otitis media. When the condition failed to respond to antibiotics, a biopsy was performed. After biopsy, further clinical and radiographic work failed to disclose any additional lesions.

Radiographic Features

Computerized tomography of the skull at the time of diagnosis showed an osteolytic defect in the left temporal bone, creating a soft tissue density. The mass resulted in left mastoid bone destruction, including the ossicular bone chain in the middle ear (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Images demonstrate CT (axial contrast-enhanced CT) scan shows left mastoid destruction and an enhancing soft-tissue mass

Diagnosis

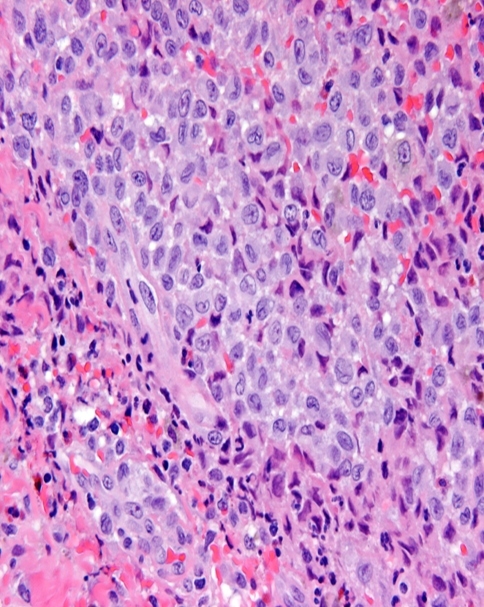

Histologic examination of hematoxylin and eosin stained slides demonstrated a collection of histiocytes with associated eosinophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells and isolated multinucleated cells (Fig. 2). The lobular, indented and folded nuclei were surrounded by a microvacuolated clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm. The nuclear chromatin was finely basophilic. Focal eosinophilic microabscesses were noted. Immunohistochemical stains showed S-100 protein and CD1a strong cytoplasmic immunoreactivity.

Fig. 2.

Photomicrograph showing a mixture of Langerhans histiocytes and eosinophils

Discussion

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a neoplastic proliferation of Langerhans cells. It has been referred to, in the past, as Letterer–Siwe disease, Hand–Schüller–Christian disease or, when solitary, eosinophilic granuloma [1]. The condition is relatively rare, occurs primarily in children and has a predilection for males [1, 2]. While it may affect soft tissue, the bone is most commonly affected, in particular the skull [2]. Involvement in the temporal bone varies according to the literature, and has been sited as low as 14% to as high as 61% [2, 3]. Temporal bone lesions may present with the signs and symptoms of an ear infection, which may result in a delay of diagnosis and treatment [4, 5]. The lack of response to antibiotics, combined with appropriate imaging studies, usually expands the clinical differential diagnosis to include Langerhans cell histiocytosis, among other lesions (such as rhabdomyosarcoma). Plain radiographs are regarded as the most accurate means of isolating LCH bone lesions [5]. The collections demonstrate a “punched out” radiolucency with a sharply defined margin [6]. Computed tomography studies (CT) are more sensitive in demonstrating the extent and progress of the disease. The CT image generally has indistinct bone margins in association with a homogeneous soft tissue mass [5]. Microscopically, the lesions are characterized by Langerhans cells, ranging in size from 10 to 15 μm, with grooved, folded, or “coffee bean” shaped nuclei, with fine nuclear chromatin, and inconspicuous nucleoli [1]. The cytoplasm is generally eosinophilic and plentiful. S-100 protein and CD1a immunoreactivity helps to confirm the lesional cells as Langerhans histiocytes. Immunohistochemistry has nearly completely replaced ultrastructural analysis, which reveals the sine quo non of Langerhans cells, the tennis racket-shaped Birbeck granule. Langerhans histiocytosis is usually associated with a rich inflammatory cell infiltrate, including lymphocytes, plasma cells, multinucleated giant cells and, usually and most impressively, large numbers of eosinophils. Eosinophils may be so numerous that microabscesses are formed, sometimes with necrosis [1]. Lesions exhibit an arc of development, with later lesions showing a greater degree of fibrosis.

The usual treatment for systemic disease associated with LCH involves radiation or chemotherapy, but localized disease is most successfully managed through surgery alone. Therefore, it is important to ascertain whether the ear and temporal bone involvement is isolated or part of systemic disease. External radiation, with doses generally in the 5–20 Gy range, chemotherapy, and steroids, may be indicated for more extensive disease. Prognosis is variable and dependent on the extent of the disease and its response to therapy [1, 3, 6].

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Dr. Kelly Koeller for contributing this case.

Disclaimer The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the author and are not to be construed as official or representing the views of the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense.

References

- 1.Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours: tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2001.

- 2.Nicholson CM, Egeker RM, Nesbit ME. The epidemiology of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1998;12:379–84. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8588(05)70517-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surico G, Muggeo P, Muggeo V, et al. Ear involvement in childhood Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Head Neck. 2000;22:42–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(200001)22:1<42::AID-HED7>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez-Latorre F, Menor-Serrano F, Alonso-Charterina S, Arenas-Jiminez J. Langerhans’ cell histiocytois of the temporal bone in pediatric patients: imaging and follow-up. Am J Radiol. 2000;174:217–21. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.1.1740217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marioni G, Filippis C, Stramare R, Carli M, Staffieri A. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis: temporal bone involvement. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115(10):839–41. doi: 10.1258/0022215011909134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boston M, Derkay CS. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone and skull base. Am J Otolaryngol. 2002;23(4):246–8. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2002.123452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]