Abstract

Kimura disease is a distinct clinicopathological entity of a benign chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology. It is endemic in Oriental Asians, but sporadic and relatively rare in the West, both in whites and blacks alike. It usually presents as a mass lesion, most commonly in the head and neck region. It had for a long time been confused as synonymous with angiolymphoid hyperplasia with esinophilia. It can impose a challenging diagnosis both clinically and pathologically, especially in non-endemic areas with unusual sites involvement. Even though it is a benign lesion, it can be life-threatening in the epiglottis with a risk of airways obstruction. So far, one case had been reported in the epiglottis with upper respiratory tract obstruction. We report a similar case with a brief review of the literature.

Keywords: Epiglottis, Kimura disease

Introduction

For a relatively long period of time and especially in the West, Kimura disease was confused with angiolymphoid hyperplasia with esinophilia. Currently, Kimura disease is considered as a separate existing entity of a benign reactive––probably immune driven––chronic inflammatory disease. It is more common in Far East Asia. It is sporadic and relatively rare in the West. It commonly involves the head and neck region as a deep/subcutaneous mass. Few cases have been reported in other sites. In certain unusual sites e.g. epiglottis, Kimura disease may impose clinical and pathological diagnostic challenges and potential pitfalls. We report a case of Kimura disease as an obstructing mass of the epiglottis.

Case Report

A 37-year old Arabic (Middle-Eastern) female presented with a four months history of difficulty in breathing as well as difficulty in swallowing, especially with solid food. The patient felt a painless fullness in the throat with worsening breathing and a choking feeling over time. On examination, a single polypoid mass which partly occluded the airway was seen to involve the posterior aspect of the epiglottis. The overlying mucosal surface was intact. The patient did not give a history of allergy or drug intake. No evidence of regional lymphadenopathy or major salivary gland enlargement was noted. Renal blood and urine tests were normal. Full blood count showed 9% peripheral esinophilia. Serum IgE was not measured. The clinical impression was of lymphoma or carcinoma. The mass was surgically removed and the postoperative course was uneventful for two weeks. The patient did not receive steroid treatment or any other medical therapy. Unfortunately, subsequent follow up of the patient was lost and no further assessment was possible.

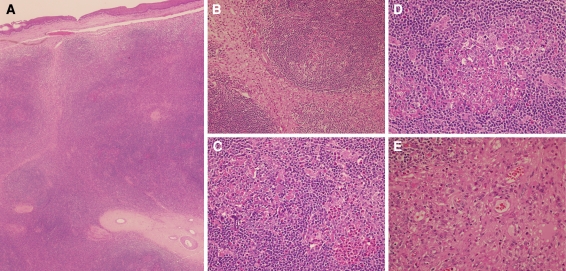

Grossly, the mass was firm polypoid yellow-tan vaguely nodular mass with intact surface. It measured 3.5 × 2.3 × 1.0 cm. Histological examination showed lymphoproliferative mass with an intact stratified squamous epithelium of the epiglottis. The core of the mass was composed of nodular collections of lymphoid cells arranged in variable sized lymphoid follicles, some with reactive germinal centers (Fig. 1a). The lymphoid follicles were separated by edematous and fibrovascular septae with esinophilic infiltrate (Fig. 1b). The lymphoid follicles showed small broken up germinal centers with characteristic pink granular to homogenous material deposition. Some germinal centers showed infiltrating esinophils and few others showed esinophilic microabscesses and esinophilic folliculolysis (Fig. 1c). Proliferating small blood vessels were also seen in the germinal centers. Characteristic polykaryocytes (Warthin-Finkeldey-type giant cells) with multiple nuclei and prominent nucleoli were also seen (Fig. 1d). The inter-follicular tissue showed mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate with a large number of esinophils along with plasma cells, small mature lymphocytes as well as histiocytes. Proliferating small post-capillary venules with flat to plump endothelial cells were present (Fig. 1e). In addition, large thick hyalinized blood vessels were evident in the septae (Fig. 1a). The edematous areas showed frequent esinophils with histiocytes and dilated venules (Fig. 1b). Immunoglobulin E (IgE) marker was not available for immunohistochemistry study.

Fig. 1.

(a) The epiglottis tissue is totally replaced by lymphoid proliferation, composed of lymphoid follicles with inter-follicular hyalinized blood vessels and fibrosed septae. Note the intact overlying surface squamous epithelium. (Hematoxylin & Eosin, original magnification × 40); (b) Reactive lymphoid follicle with maintained mantle zone and adjacent expanded inter-follicular septa with fibrosis and edema and with large number of esinophils. Note the absence of tingible body macrophages in the germinal centers. (Hematoxylin & Eosin, original magnification × 200); (c) Two lymphoid follicles are seen, one with aggregates of esinophils forming esinophilic microabscess and esinophilic folliculolysis and the other lymphoid follicle showing pink proteinaceous material with dismantling of the germinal center. (Hematoxylin & Eosin, original magnification × 400); (d) Lymphoid follicle showing prominent pink material deposition, esinophilic infiltration, proliferating small blood vessels and partial folliculolysis of the germinal center. Note the scattered multinucleated giant cells involving the germinal center and the interfollicular lymphoid tissue (H&E, original magnification × 400); (e) Inter-follicular septa with proliferating post-capillary venules with flat to plump endothelial cells, fibrosis and infiltrating esinophils. Note the absence of epithelioid-like endothelial cells (H&E, original magnification × 400)

Discussion

Kimura disease (KD) is currently considered as a benign reactive chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown pathogenesis and of uncertain etiology [1–5]. For a relatively long period of time and especially in the West, it was considered as a late stage of angiolymphoid hyperplasia with esinophilia (ALHE) [5]. The development of its concept and its separation from ALHE had undergone several changes, since its first description in the literature (Table 1) [1, 3, 5–8]. KD typically presents as a tumor-like mass in the head and neck region [1–3]. It is considered as a relatively rare lesion––both in whites and blacks––in the West, while it is endemic in Far East Asians [1, 2, 4, 9]. It is more common in males [1, 2, 4, 7, 9]. Even though, KD is mostly a head and neck lesion, few cases were reported in other locations e.g. axilla, trunk and groin [1, 9, 10]. Involvement of the epiglottis is very unusual and probably a very rare occurrence. Similar to our case, Cho et al. reported one case of KD presenting as an obstructing mass of the epiglottis in a young Asian male [10]. Occurrence of KD in the epiglottis can impose a challenging diagnostic workup for both clinicians and pathologists. In addition, we believe that even though KD is considered as a benign lesion, it can be life-threatening in the epiglottis, since it has a potential for upper airways obstruction.

Table 1.

Development of the concept of Kimura disease

| Year | Source | Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| 1937 | Kim & Szeuto(China) | First description in the literature of KD as “Esinophilic hyperplastic lymphogranuloma” |

| 1948 | Kimura et al.(Japan) | Described KD as “Unusual granulation combined with hyperplastic changes of lymphatic tissue” |

| 1959 | Iisuka(Japan) | First to give the name “Kimura disease” to their case of esinophilic lymphadenitis and granulomatosis |

| 1969 | Wells & Whimster(West) | First to link KD to ALHE; causing confusion in the West between the two entities |

| 1979 | Rosai et al.(West) | Excluded KD from histiocytoid hemangioma,but retained ALHE under the concept of histiocytoid hemangioma |

| 1987 | Googe et al.(USA) and Urabe et al.(Japan) (independently) | First to separate KD from ALHE as two distinct clinicopathological entities |

| 1988 | Kuo et al.(Taiwan) | Confirmed the concept of KD as a separate clinicopathological entity from ALHE |

| 2002 | Chim et al.(Hong Kong) | Claimed T-cell clonatity of KD based on a single case report |

KD: Kimura disease, ALHE: Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia

Clinical differential diagnoses––especially with the presence of regional lymphadenopathy––may include viral infection, lymphoma or carcinoma. Knowledge of the presence of peripheral esinophilia should guide the clinician to the possibility of KD [4, 10]. The final diagnosis is usually established with histological examination. Fine needle aspiration is not always diagnostic for KD, and can only help in confirming recurrent cases [6].

Histological differential diagnosis may include ALHE, florid follicular hyperplasia, parasitic/allergic reaction, Castleman disease (CD), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), and Langerhans histiocytosis (LH) [1, 3, 11]. KD has certain basic and constant features which can help in confirming the diagnosis and excluding other possibilities (Table 2). We feel the most important features are those of the germinal centers. Germinal centers in KD have characteristic features which include: granular to linear deposition of esinophilic-pink proteinaceous material, vascularization with infiltration of small blood vessels into the germinal centers, infiltration of esinophils right into the germinal centers with occasional esinophilic microabscess formation with/without esinophilic folliculolysis, and the presence of multinucleated giant cells(polykaryocytes) of the Warthin-Finkeldey type within the germinal centers [1, 2, 6, 7, 11, 12]. A constant feature of KD is the pattern of esinophilic infiltrate. Esinophils are present in large numbers in the interfollicular septae, the perinodal stroma as well as the mantle zone and the germinal centers of the lymphoid follicles [2, 5–7, 12]. Esinophilic microabscess formation with/without Charcot-Leyden crystals is another less frequent, but characteristic finding [7]. These features may be shared by other lesions, for example, ALHE, CD, HL and LH, but strict adherence to the above mentioned criteria can help to rule out these mimickers. A very important histological differential diagnosis and pitfall to be avoided is ALHE. The important and helpful features differentiating KD from ALHE are summarized in (Table 2) [5, 7–12]. CD has characteristic “onion-skin” layering of the mantle zone with hyalinized blood vessels in the germinal centers. It lacks esinophilic folliculolysis and the esinophils are usually confined within the interfollicular areas. In difficult cases, use of immunohistochemistry study can help. CD usually expresses HHV-8 marker and lacks IgE deposition in the germinal centers. The polykaryocytes in KD can impose a potential pitfall with HL and LH. KD usually lacks the typical Reed-Sternberg cells of classic HL. LH shows large number of atypical histiocytes with characteristic nuclear grooves and usually shows a sinusoidal growth pattern. We observed that the germinal centers of KD––in contrast with those of florid follicular hyperplasia––usually have reduced or sometimes absent tingible body macrophages (Fig. 1b). This observation along with the other characteristic features of KD can help in excluding the “simple” follicular hyperplasia. Parasitic and allergic reaction can be excluded by proper clinical investigations and the absence of parasitic organisms by the use of specific special stains.

Table 2.

Kimura disease (KD) versus angiolymphoid hyperplasia with esinophilia (ALHE)

| KD | ALHE |

|---|---|

| Young adults (mean age 26 years) | Older adults(mean age 39 years) |

| Male > female | Male > Female |

| Endemic in orient (sporadic in West) | More common in Caucasians |

| Single large mass (2–10 cm) | Multiple small nodules (0.5 –2 cm) |

| Can be Bilateral | Unilateral |

| Deep seated soft-tissue/subcutaneous | Superficial/dermal |

| Longer duration (3–9 years) | Shorter duration (2–3 years) |

| Regional lymphadenopathy––common | Regional lymphadenopathy-absent |

| Peripheral esinophilia and raised serum IgE––common | Peripheral esinophilia and raised serum IgE––less common |

| Overlying skin––intact | Overlying skin––involved |

| Prominent lymphoid follicles | Less prominent lymphoid follicles |

| Esinophilic infiltrate and folliculolysis of germinal centers | Not a feature |

| Pink proteinaceous material and infiltrating blood vessels in germinal centers | Absent |

| Flat to plump endothelium of post-capillary Venules | Epithelioid/vacuolated endothelium |

| Hyalinized interfollicular blood vessels | Not a feature |

| AV-shunt not a feature | AV-shunt is a frequent feature |

| Interfollicular/Intersitial fibrosis-common | Not a constant feature |

| IgE deposition in germinal centers | Not proven |

| Can be associated with nephrotic syndrome | Not reported |

| Benign clinical course with recurrence | Protracted, reluctant course with recurrence |

| Can respond to steroid treatment | Not proven |

| Immunologically-mediated chronic inflammatory disorder | Clonal neoplastic endothelial tumor |

IgE: Immunoglobulin E, AV-shunt: Arterio-Venous Shunt

The exact etiology and pathogenesis of KD are not yet well established [1, 2]. The presence of reactive lymphoid follicles with polykaryocytes similar to Warthin-Finkeldey giant cells of measles may suggest a viral infection as a possible causative agent. The large number of esinophils may raise the suspicion of hypersensitivity or parasitic reaction. The discovery of some cases to be associated with renal glomerular disease in the form of nephrotic syndrome and the demonstration of IgE deposition in the renal glomeruli as well as in the germinal centers of the involved lymph nodes, support the notion that KD is an aberrant immune response i.e.; autoimmune disorder [1, 7, 9, 11]. In addition, the response to steroid therapy in some cases may further support this theory [1, 2, 4–6, 11]. Recently, Chim et al. suggested a clonal T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder that may contribute––at least partly––to the pathogenesis of KD [3]. However, this observation was based on a single case study and was not validated by subsequent studies [1–3]. In addition, no malignant transformation was reported so far to be associated with KD [3, 6, 11].

Surgical resection is the primary treatment for KD [1, 6]. Additional optional medical treatment may include steroid therapy, chemotherapy and radiation [1, 6]. Even though KD is considered as a benign self-limited lesion with good prognosis, local and/or distal recurrence can occur [1–3, 6, 11].

In conclusion, KD is usually endemic in Oriental Asians, while relatively rare in the West. It has been confused with ALHE for a long period of time in the West. However, KD is nowadays considered as a completely distinct clinicopathological entity. It commonly involves the head and neck region. KD, in unusual sites, can be a challenging clinical and pathological diagnosis. Attention to certain characteristic histological features can help in confirming the diagnosis of KD and in excluding other mimickers including ALHE. Even though, KD is considered as a self-limited benign chronic inflammatory disease, it can be a life-threatening lesion in the epiglottis due to its mass effect and therefore a potential for upper airways obstruction.

Footnotes

The Department to which the work should be attributed: Histopathology Department, Armed Forces hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

References

- 1.Abuel-Haija M, Hurford MT. Kimura disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:650–1. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-650-KD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen H, Thompson LD, Aguilera NS, et al. Kimura’s disease: a clinicopathological study of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:505–13. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200404000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuo TT, Shih LY, Chan HL. Kimura’s disease: Involvement of regional lymph nodes and distinction from angiolymphoid hyperplasia with esinophilia. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:843–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taskin M, Goksalan T, Kakani R, et al. Pathologic quiz case1. Pathologic diagnosis; Kimura’s disease. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:893–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urabe A, Tsuneyoshi M, Enjoji M. Epithelioid hemangioma vs. Kimura’s disease. A comparative clinicopathological study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:758–66. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198710000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chim C, Fung A, Shek T, et al. Analysis of clonality in Kimura’s disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1083–6. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200208000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Googe PB, Harris NL, Mihm MC., Jr Kimura disease and angiolymphoid hyperplasia with esinophilia. Two distinct histopathological entities. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:263–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1987.tb00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosai J, Gold J, Landy R. The histiocytoid hemangioma: a unifying concept embracing several previously described entities of skin, soft tissue, large vessels, bone and heart. Hum Pathol. 1979;10:707–30. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(79)80114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gumbs MA, Pai NB, Saraiya RJ, et al. Kimura’s disease: a case report and literature review. J Surg Oncol. 1999;70:190–3. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199903)70:3<190::AID-JSO9>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho MS, Kim ES, Kim HJ, et al. Kimura’s disease of the epiglottis. Histopathology. 1997;30:592–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.5480804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen TG, Helwig EB. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with esinophilia: a clinicopathological study of 116 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:781–96. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(85)70098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajpot DK, Pahl M, Clark J. Nephrotic syndrome associated with Kimura’s disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14:486–8. doi: 10.1007/s004670050799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]