Clinical Presentation

An 11-year old girl presented with a 2 year history of gingival swelling (Fig. 1).

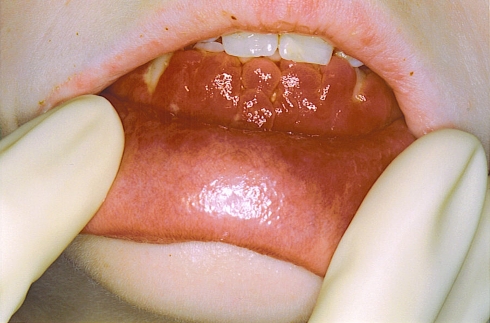

Fig. 1.

Clinical photograph showing exuberant gingival swelling in the anterior mandibular region

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical photograph (Fig. 1) shows the obvious labial gingival enlargement in the area of the mandibular anterior teeth, extending to the incisal edges of these teeth. In addition, multiple focal areas of pigmentation on the lips, erythema of the lower labial mucosa, an area of ulceration at the gingival margin, and generalised facial pallor are noted.

Further useful information would include a history of the presenting complaint, signs and symptoms, including systemic involvement; whether there was any observed spontaneous haemorrhage from the gingiva; the onset of gingival enlargement as gradual or sudden; and changes in size or nature of the lesions.

A thorough medical history including current medications, allergies and systems review, in particular a history of organ transplant, diabetes mellitus, epilepsy and gastrointestinal signs and symptoms may contribute to forming at a differential diagnosis. A family history should also be taken, including congenital or hereditary conditions, and enquiry about similar lesions affecting the patient’s siblings. The dental history would reveal her attendance record as well as oral hygiene habits.

Further extra-oral examination should include palpation for regional lymphadenopathy, observation of any obvious facial swelling or asymmetry and trismus. In addition, extra-oral ecchymosis or petechiae, as well as any cutaneous lesions should be noted.

Intra-orally, abnormalities of tooth number, size and structure should be noted, as well as whether the dentition was consistent with the age and development of the patient.

Additional soft tissue examination should note any areas of spontaneous bleeding, bleeding on probing, tenderness to palpation, as well presence and location of other lesions including areas of petechiae or ecchymosis. Signs of possible underlying bony involvement should be recorded, as well as the standard of oral hygiene.

The differential diagnoses of chronic generalised gingival enlargement in a paediatric patient can be classified according to aetiopathogenesis. Congenital and hereditary conditions include hereditary gingival fibromatosis, various lysosomal storage diseases, primary amyloidosis, and other inherited conditions. In general, the appearance of the gingival enlargement in these disorders is more bulbous and fibrous than the friable, erythematous enlargement noted in this patient. In addition, inherited and congenital causes of gingival enlargement would usually become apparent once the patient’s medical history was taken, however genetic testing may be used to confirm any genetic abnormality.

Immunological conditions that may manifest as gingival enlargement include Crohn’s disease, orofacial granulomatosis (OFG) and Wegener’s granulomatosis, however, the latter is quite rare in the paediatric population. Investigations for Crohn’s disease or OFG would include: full blood count (FBC), screening for haematinic deficiencies, anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody (ASCA), perinuclear-anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody (p-ANCA). If inflammatory bowel conditions were suspected, referral for gastroenterology review may be necessary. Investigations for Wegener’s granulomatosis would entail testing for cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasm antibody (c-ANCA) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) in addition to the FBC.

Conditions of inflammatory, metabolic and endocrine origin include chronic hyperplastic gingivitis, puberty gingivitis and diabetes mellitus-related gingival hyperplasia also form part of the differential diagnosis, although the gingival hyperplasia seen in these settings generally result from poor oral hygiene and would improve with a thorough dental scaling and oral hygiene measures. Further testing for diabetes mellitus would include blood sugar and glycosylated haemoglobin levels.

The nutritional deficiency of ascorbic acid, causing scurvy, also needs to be considered, and could be confirmed by a serum ascorbic acid level.

Neoplastic or haematological conditions such as leukaemia and lymphoma (although unlikely given the 2 year history), histiocytic diseases including Langerhans cell histiocytosis, aplastic anaemia, and Kaposi’s sarcoma may also manifest as gingival enlargement. Tests for leukaemia, lymphoma, histiocytic diseases, and aplastic anaemia would include a FBC, differential white cell count, as well as a blood film. If Kaposi’s sarcoma was suspected, HIV serology could be performed.

Iatrogenic causes, mainly drug related gingival enlargement is commonly seen in patients taking cyclosporin, phenytoin and other anticonvulsant medications, as well as various calcium channel blockers. This would become apparent through the patient’s medical history, and should improve following a thorough dental scaling and oral hygiene measures.

Finally, sarcoidosis may also manifest as gingival enlargement, however, this condition is rare in children and adolescents. Investigations would include an angiotensin converting enzyme level (ACE), as well as a chest radiograph checking for hilar lymphadenopathy.

Other general investigations would include dental radiographs, in particular plain films—periapical views and orthopantomogram, to determine whether these lesions were confined to the soft tissues, or whether there was underlying bony involvement. In addition, tests for tooth mobility, tenderness to percussion and tooth vitality testing could be helpful.

Further actions include an initial thorough scale and polish to exclude any oral hygiene or plaque related factors, followed by a biopsy of the lesional tissue for histopathological examination to reach a definitive diagnosis.

Diagnosis and Discussion

In February 2004, when the patient was 9 years old, she was referred by her dentist to one of the authors of this paper because of gingival swelling. This was first noticed in June 2003, and in December 2003 the dentist noted that the gingivae were erythematous. There was a good response to antibacterial mouthwashes and electric tooth brushing twice daily. At the time, generalised gingival hyperplasia and erythema, with marked bleeding on probing and minimal plaque accumulation was observed. No epithelial tags, ulceration or other mucosal lesions were noted. Clinically, OFG was suspected but in view of the reported improvement with local measures further investigations were deferred. The patient did not attend for review, reporting that the condition was “much better”.

In February 2005 the patient was seen by a periodontist for continued gingival overgrowth. Florid gingival hyperplasia in the mandibular anterior region together with ulceration was observed and a provisional diagnosis of “puberty gingivitis” was made. Haematological investigations showed “some abnormalities”. There was no improvement in the gingival condition with local periodontal measures, so a biopsy of the hyperplastic tissue from the mandibular incisor area was taken. (Fig. 1) The patient reported that this area had developed within a period of 48 h. The excision site healed well.

The clinical notes submitted with the specimen were: “Swollen interdental papilla, originally covering entire incisal edges of mandibular incisors. Previous episode 1 year ago in maxillary central incisor area”. This specimen consisted of a mass of collagenous fibrous tissue covered by epithelium. The epithelium was irregular in thickness. Chronic inflammatory cells diffusely and densely infiltrated the connective tissue. Foci of calcification were also noted. The histopathological features were in keeping with a fibrous epulis (a localised chronic inflammatory hyperplasia of the gingivae) with the calcification indicating previous ulceration.

In October 2005 the patient re-presented to the periodontist with a “similar appearance”. The buccal mucosa adjacent to the mandibular canines was now erythematous and ulcerated, and was suggested as being “an appearance of trauma, either a burn or possibly allergic reaction”. The patient was then referred to another of the authors of this paper. At the time of clinical examination in November 2005 the patient’s upper lip appeared slightly swollen although this was denied by the patient and her mother. There was generalised gingival swelling and erythema in the anterior parts of the mouth but sparing the mandibular molar segments. Ulceration was noted in the mandibular left premolar buccal sulcus and folds of hyperplastic tissue were found in the mandibular right premolar buccal sulcus. The clinical appearances were felt to be suggestive of a diagnosis of OFG.

As OFG can be a manifestation of Crohn’s disease further questioning was directed towards any abdominal signs or symptoms. The patient reported abdominal pain only with exertion (a “stitch”), no altered bowel habits, no extra-oral swellings (in particular, no perianal skin tags). The patient was 153 cm tall (approximately 80th centile) and 47 kg in weight (approximately 80th centile). She was amenorrhoeic but was reported to show early breast development. She was also being investigated regarding a mild proteinuria, possibly a result of a post-streptococcal or staphylococcal glomerulonephritis. Haematological investigations performed were a FBC, ESR, C-reactive protein, iron studies, vitamin B12, folate, calcium, albumin and liver function tests. These showed a mild macrocytosis with a mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of 95fL (75-90fL), a raised ESR of 21 mm/h (0–10 mm/h), a slightly reduced serum albumin of 36 g/l (38–50 g/l) and a slightly elevated alkaline phosphatase level of 360 U/l (80–350 U/l). All other results were within the normal range.

The original histopathology was reviewed in light of the further information regarding the extent of the previous gingival swelling. Occasional multinucleate giant cells were identified in association with the fragments of calcified material. No definite granulomas were found. The diagnosis of a fibrous epulis with calcification was felt to be untenable in view of the generalised rather than localised swelling. It was concluded that this represented hyperplastic and inflamed gingival tissue. Further biopsies were performed of the hyperplastic tissue in the mandibular right buccal sulcus and the adjacent right mandibular gingivae. The former consisted of intensely inflamed fibrous tissue covered by irregularly hyperplastic stratified squamous epithelium. There was no evidence of granulomatous inflammation, nor were any multinucleate giant cells identified. The latter biopsy also featured a dense inflammatory infiltrate with both acute and chronic inflammatory cells present. There was a covering of irregularly hyperplastic epithelium. A region of ulceration was also noted. Occasional isolated multinucleate giant cells were identified, although one focus of clustered giant cells was noted (Fig. 2), and felt to be suggestive of a diagnosis of OFG.

Fig. 2.

Photomicrograph of the November 2005 biopsy of the mandibular gingivae showing a cluster of multinucleate giant cells, suggestive of a diagnosis of orofacial granulomatosis

In view of the clinical, histopathological and haematological findings the patient was referred for gastroenterology review.

One week post-biopsy, there was swelling of the interdental papilla between the maxillary right central and lateral incisors and a similar but lesser swelling between the maxillary left central and lateral incisors. These were excised, with the swelling from the right side featuring a chronic inflammatory infiltrate with a central region of multinucleate giant cells in a cellular and vascular immature fibrous connective tissue stroma (Fig. 3). The swelling on the left side showed evidence of chronic inflammation without any significant numbers of giant cells. A small collection of multinucleate foreign body giant cells was also present in one area. Calcification was seen at the base of this specimen. The specimen from the right side was diagnosed as a giant cell granuloma. A comment was made in the report “as with all giant cell lesions, hyperparathyroidism needs to be excluded”. The swelling on the left side was diagnosed as a fibrous epulis with calcification and some features suggestive of orofacial granulomatosis. Haematological investigations were carried out to identify or exclude hyperparathyroidism. The serum calcium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase and parathyroid hormone levels were all within normal limits.

Fig. 3.

Photomicrograph of the gingival swelling from the right maxilla showing sheets of multinucleate giant cells in a cellular and vascular immature fibrous connective tissue stroma consistent with a diagnosis of a giant cell granuloma

In March 2006 the patient returned with a recurrence of the swelling in the maxillary right central/lateral incisor region. The remainder of the gingivae was less swollen. The hyperplastic lesion in the mandibular right buccal sulcus had resolved. The swelling was again excised and histopathology showed identical features to those of the specimen from the same site in December 2005. This was therefore regarded as a recurrent giant cell granuloma.

During the course of 2006 the patient was investigated for possible Crohn’s disease. Gastroscopy and colonoscopy were performed but no abnormalities were found. Multiple biopsies were reported as normal. By mid-2006 the patient’s mother reported that that patient’s “gums were now 100%”. The patient was then lost to review.

Inquiries made into the patient’s progress in June 2008 revealed that the patient was having professional cleaning by a dental hygienist every three months and was taking amphotericin B lozenges. According to the dentist and the patient’s mother, there was some gingival erythema but the gingival condition had improved considerably, although she experienced recurrent ulceration in the mandibular buccal sulci. In recent months she had experienced stomach cramps, episodes of diarrhoea and constipation and had developed a tear in her anal passage.

This patient shows some features consistent with a diagnosis of OFG, one of a number of granulomatous disorders affecting the orofacial region [1]. No evidence of Crohn’s disease was found in 2006; however, the recent information regarding abdominal signs and symptoms suggests that reinvestigation might now be considered. OFG was a term coined by Wiesenfeld et al. [2] Subsequently it has been suggested that the term OFG be prefaced by the word idiopathic to distinguish it from patients with oral manifestations of Crohn’s disease or sarcoidosis. It probably includes Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (a triad of granulomatous swelling of the lips, a fissured tongue and facial palsy) and cheilitis granulomatosa (which is indistinguishable from OFG, but does not have anything other than lip involvement). The condition affects males and females of all ages. It typically presents with recurrent/persistent swelling of the lips, cheeks and buccal mucosa with hyperplastic tags in the sulci and floor of mouth, often with ulceration and gingival swelling and erythema. Histopathology shows non-caseating granulomas. No birefringent material is identified under polarised light, mycobacteria are not seen in Ziehl-Neelsen stained slides and no fungi are identified with stains such as Grocott or periodic acid Schiff. There is often intense inflammation adjacent to the overlying epithelium. The granulomas may be sparse, poorly-formed and deep. The aetiology is uncertain [3]. Some cases are best classified as idiopathic. A genetic predisposition has not been established, in contrast to other inflammatory bowel diseases where there is a considerable weight of evidence for a genetic basis [4]. Some patients show evidence of sensitivity to food including cinnamon, monosodium glutamate and chocolate.

The further investigation of patients with OFG should exclude mycobacterial and fungal infection as well as excluding sarcoidosis. Crohn’s disease needs to be considered if there are any symptoms or signs consistent with inflammatory bowel disease. Haematological investigation including FBC, iron studies, folate, B12, calcium and albumin can identify malabsorption. The possibility of Crohn’s disease needs to be re-considered over a period of time. Management of OFG in children and adolescents is problematic [5, 6]. Some patients require simple reassurance and monitoring rather than active intervention. An elimination diet and exclusion of any identified sensitisers is appropriate for some patients. Topical or local corticosteroid treatment has been advocated by some authors and systemic steroids may be warranted for those patients with significant swelling causing psychological problems. Other immunomodifiers have also been advocated. Surgery has also been suggested but recurrence is probable. If Crohn’s disease is diagnosed, the oral lesions may improve when the gastrointestinal condition is managed. The same would apply to sarcoidosis. It is contentious whether patients with only oral lesions should be actively treated given the possible adverse effects of medication.

This patient is somewhat unusual for the propensity to develop discrete inflammatory and/or giant cell swellings of the gingivae. We believe that this represents an exaggeration of the OFG, possibly modulated by oral hygiene. This appearance, however, does not seem to have been reported previously in OFG.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Finlay Macrae, Consultant Physician and Gastroenterologist and Head of Colorectal Medicine and Genetics at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, Australia and Associate Professor Don Cameron, Paediatric & Adolescent Gastroenterologist and Head of the Paediatric Gastroenterology at Monash Medical Centre and Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia for their assistance in investigating this patient.

Contributor Information

Michael J. Aldred, Email: michael.aldred@sctelco.net.au

Sue-Ching Yeoh, Email: scyeoh@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Eveson JW. Granulomatous disorders of the oral mucosa. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1996;13:118–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiesenfeld D, Ferguson MM, Mitchell DN, et al. Oro-facial granulomatosis—a clinical and pathological analysis. Q J Med. 1985;54:101–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tilakaratne WM, Freysdottir J, Fortune F. Orofacial granulomatosis: review on aetiology and pathogenesis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:191–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. OMIM (TM). Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD. MIM Number: MIM 266600. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/. Accessed on 1 July 2008.

- 5.Sainsbury CP, Dodge JA, Walker DM, et al. Orofacial granulomatosis in childhood. Br Dent J. 1987;163:154–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4806225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clayden AM, Bleys CM, Jones SF, et al. Orofacial granulomatosis: a diagnostic problem for the unwary and a management dilemma. Case reports. Aust Dent J. 1997;42:228–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1997.tb00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]