Abstract

Sclerosing polycystic adenosis (SPA) is a rare lesion of salivary glands with a striking resemblance to fibrocystic disease of the breast. Most of the 47 reported cases have occurred within the parotid gland, with only a single case being described within the buccal mucosa. We report an additional case of SPA of the buccal mucosa. The exact nature of this entity is unknown, but has up until recently believed to be a pseudoneoplastic reactive and inflammatory sclerosing process. Even though SPA has satisfied the criteria for monoclonality, the debate as to whether SPA represents a true neoplasm or a pseudoneoplastic inflammatory sclerosing process, with low-grade neoplastic potential continues. Awareness of the occurrence of this lesion in both major and minor salivary glands is important to promote its differentiation from other more sinister salivary gland pathology. Cure is effected by localized surgical excision and all reported cases of SPA show an excellent prognosis with no true recurrence or metastasis.

Keywords: Sclerosing polycystic adenosis, Salivary glands, Immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Sclerosing polycystic adenosis (SPA) is a newly reported, extremely uncommon, yet distinctive pseudoneoplastic, reactive, inflammatory process of the major and minor salivary glands that closely resembles fibroadenosis tumors of the breast. Since the original reported cases from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology [1] there have been 47 cases of SPA in the literature [1–10]. Most cases occurred within the major salivary glands, and only sporadic cases have been reported within the minor salivary glands, with only one of these being in the buccal mucosa [5]. We report an additional case of SPA occurring within the minor salivary glands of the buccal mucosa.

Case Report

Clinical Findings

A 35-year-old black man presented with a single, firm, non-tender nodule in the right buccal mucosa measuring 2 cm in greatest dimension. The surface of the lesion was smooth and non-ulcerated. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable. The clinical differential diagnosis included a benign salivary gland tumor and a mucous extravasation cyst.

Pathological Findings

Gross Pathology

An excisional biopsy was performed with the patient under local anesthesia and this was submitted for histopathologic examination. On gross pathologic examination, the lesion was well circumscribed, firm, and rubbery and measured 1.8 × 1.5 × 1.3 cm3. The cut surface was pale cream-white in color, glistening and had scattered tiny cysts of about 1–2 mm.

Histopathology

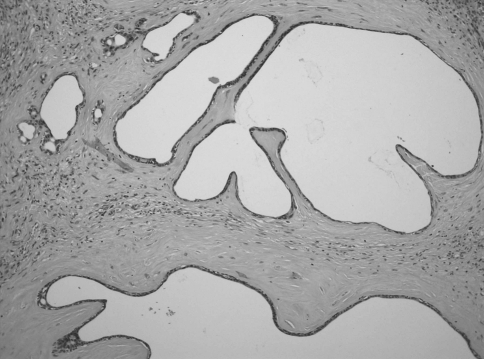

Microscopically, there was a well circumscribed, non-encapsulated nodule, composed of multiple vague densely sclerotic irregular lobules, with abundant intervening hyalinized collagen bundles, surrounding cystically dilated ducts of variable size (Figs. 1 and 2). The ducts were lined by flattened epithelium, with no evidence of squamous or mucous metaplasia. Occasional ductal and acinar components showed focal areas of apocrine-like metaplasia. Dysplastic epithelium was not evident. Surrounding proliferating spindle shape myoepithelial cells were present. There was a surrounding moderately intense chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. Residual minor mucous secreting salivary glands were present at the periphery. There were no cytological or architectural features of malignancy in the sections examined. The histomorphology of the lesion bore a strong resemblance to fibrocystic change of the breast, however even though sclerosis was evident, marked adenosis of the ductal elements and acini was lacking.

Fig. 1.

Low-power photomicrograph of polycystic sclerosing adenosis showing a circumscribed proliferation of micro- and macrocysts, ducts, and acinar structures in a lobular densely sclerotic stroma. (hematoxylin-eosin stain, original magnification 100×)

Fig. 2.

Cystically dilated ductal elements with marked circumferential sclerosis and focal aggregates of chronic inflammation (hematoxylin-eosin stain, original magnification 200×)

Histochemistry and Immunohistochemistry

Special staining with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), with and without diastase digestion, and mucicarmine failed to demonstrate the presence of intracellular mucin. Immunohistochemistry in the presence of adequate controls and preparations, showed positivity with cytokeratin MNF116 and M3515 cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) (Dako; Glostrup, Denmark) in the ductal lining cells of the tubuloacinar elements, with preservation of the normal lobular architecture. The S-100 protein (Dako; Glostrup, Denmark) highlighted both the ductal cells and the spindled myoepithelial cells, which surrounded the ductal and acinar structures. P63 (Dako; Glostrup, Denmark) stained the peripheral layer of cells surrounding the acini, ducts, and cystic spaces, clearly outlining these structures (Fig. 3). A diagnosis of SPA was made, and the lesion was widely excised. There has been no recurrence of the lesion to date (21 months).

Fig. 3.

Immunopositivity with p63 confirming the continuous abluminal myoepithelial layer, surrounding nearly every ductal, and acinar structure (p63 (Dako; Glostrup, Denmark), original magnification 400×)

Discussion

Sclerosing polycystic adenosis was first described by Smith et al. [1] in 1996. It is an extremely rare lesion, of uncertain nature somewhat similar to fibrocystic disease and adenosis of the breast. Gnepp et al. [5] initially found 22 reported cases and added a further 15 new cases. In addition to the further study by Skálová et al. [6] there have been a few recent case reports, including those described in the minor salivary glands by Noonan et al. [7]. As far as we know, including the current case, there have now been 48 cases of SPA reported in the literature [1–12]. Review of the available clinical features of the reported cases, some of which are summarized in Table 1, showed predominance in the parotid gland (80.5%), rare involvement of the submandibular gland (7.3%), and more recently, involvement of the minor salivary glands (12.2%) has been documented [9]. The latter sites included the mucobuccal fold, hard palate, and floor of mouth, with only a single case previously reported within the buccal mucosa [5]. The age distribution was wide, ranging from 9 to 84 years (mean 42.4 years; median 43 years). Most patients were within the fourth and fifth decades of life. There were 19 males (46.3%) and 22 females (53.7%) in the series. The lesions ranged in size from 0.3 to 7 cm [5, 11].

Table 1.

Some reported cases of sclerosing polycystic adenosis

| Reference | Cumulative unique reported cases with clinical data | Gender | Age (years) | Site | Recurrence (r) postoperative | Presence of ductal atypia/dysplasia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smith et al. [1] | 1 | M | 26 | R Parotid | Lost to follow up | 0 |

| 2 | M | 39 | Submandibular | Lost to follow up | 0 | |

| 3 | F | 32 | R Parotid | Lost to follow up | 0 | |

| 4 | M | 63 | Parotid | Died, 0 at 27 months | 0 | |

| 5 | F | 16 | L Parotid | 0 at 17 months | 0 | |

| 6 | M | 17 | R Parotid | 0 at 7 months | 0 | |

| 7 | F | 16 | Parotid | r at 56 months; 0 at 30 months | 0 | |

| 8 | F | 31 | L Parotid | 0 at 16 mo | 0 | |

| 9 | F | 12 | Parotid | r at 72 and 336 months; multiple over 108 months; 0 at 24 months | 0 | |

| Batsakis [2] | 10 | F | 13 | Parotid | 0 | 0 |

| Skálová et al. [3] | 11 | F | 31 | R Parotid | 0 at 36 months | severe |

| 12 | F | 27 | R Parotid | 0 at 48 months | 0 | |

| 13 | F | 9 | L Parotid | r at 156 months | mild | |

| Imamura et al. [4] | 14 | M | 20 | L Parotid | 0 | mild |

| Gnepp et al. [5] | 15 | F | 46 | R Parotid | 0 at 62 months | severe |

| 16 | F | 44 | R Parotid | 0 at 96 months | severe | |

| 17 | M | 42 | Parotid | 0 at 49 months | mild | |

| 18 | M | 32 | Parotid | 0 at 168 months | 0 | |

| 19 | F | 43 | L Parotid | 0 at 60 months | mild | |

| 20 | F | 51 | L Parotid | 0 at 79 months | moderate to severe | |

| 21 | F | 47 | Parotid | 0 at 36 months | 0 | |

| 22 | M | Middle age | Parotid | 0 at 480 months | 0 | |

| 23 | M | 49 | R Parotid | 0 at 31 months | 0 | |

| 24 | M | 45 | Submandibular | 0 at 18 months | severe | |

| 25 | M | 75 | Buccal mucosa | 0 at 33 months | mild | |

| 26 | M | 35 | L Parotid | 0 at 34 months | severe | |

| 27 | M | 28 | R Submandibular | 0 at 34 months | moderate to severe | |

| 28 | F | 67 | R Parotid | NA | severe | |

| 29 | M | 55 | R Parotid | 0 at 54 months | mild to moderate | |

| Skálová et al. [6] | 30 | F | 35 | R Parotid | NA | nuclear pleomorphism present in cases 30 to 35 ranging from mild to severe to low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ |

| 31 | F | 24 | L Parotid | 0 at 24 months | ||

| 32 | F | 64 | R Parotid | Lost to follow up | ||

| 33 | M | 72 | L Parotid | 0 at 36 months | ||

| 34 | F | 31 | R Parotid | 0 at 24 months | ||

| 35 | M | 58 | Parotid | 0 at 24 months | ||

| Noonan et al. [7] | 36 | F | 48 | L Maxillary mucobuccal fold | 0 at 15 months | 0 |

| 37 | M | 80 | R Floor of mouth | Lost to follow up | 0 | |

| 38 | M | 70 | L Hard palate | 0 at 13 months | 0 | |

| Kloppenborg et al. [8] | 39 | NA | 55 | NA | NA | NA |

| Bharadwaj et al. [9] | 40 | F | 45 | L Parotid | 0 at 36 months | mild cytologic atypia |

| Etit et al. [10] | 41 | F | 84 | Parotid | NA | 0 |

| Meer (this study) | 42 | M | 35 | Buccal mucosa | 0 at 21 months | 0 |

Minor sites highlighted in bold; NA, not available

Typically, SPA of the minor salivary glands presented as asymptomatic, firm, smooth, freely movable submucosal nodules that are white, cream, or yellow in color. SPA of the major salivary glands, especially the parotid gland, were slow growing, deep-seated, rounded, palpable masses, with or without associated pain, and tenderness. The typical gross pathologic finding was that of well circumscribed, rubbery firm masses with pale cream-white-yellow glistening cut surfaces showing multinodularity, and several tiny cysts, measuring about 1–2 mm in diameter.

Gnepp et al. [5] described a wide range of histological appearances. The lesions were typically well circumscribed, yet unencapsulated, and consisted of a proliferation of microcysts, ducts, and acinar structures in a densely sclerotic stroma. Irregularly defined lobules of abundant hyalinized collagen surrounded variably sized ducts, many of which were cystically dilated. The number of ducts and the size of the cysts varied between the cases. Occasional closely packed small ductular elements and strangulated tubules reminiscent of sclerosing adenosis of the breast may be seen. The current case exhibited paucity of the adenosis component, which should be considered within the histomorphologic spectrum of these lesions. The ducts were lined by flattened to cuboidal epithelial cells, with some cells exhibiting apocrine-like metaplasia, manifested by well-defined apical snouting into the ductal lumina [10].

Whilst mucous, sebaceous, squamous, foamy, vacuolated, and ballooned cells as well as brightly stained eosinophilic zymogen granules within some tubulo-acinar structures are described in SPA [12], our case was devoid of any of these features. This diverse histomorphologic spectrum is well documented in SPA of both the major and minor salivary glands and as evidenced from the current case, is of no prognostic significance. However, familiarity with the cytomorphologic features of SPA, including its characteristic apocrine changes is important in the delineation of SPA from other salivary gland pathology [10]. There may be few to many zymogen granules, and it is important not to mistake them for oncocytosis or intracellular mucin. These variable yet distinct histological growth patterns further clarify this uncommon lesion, and aid in its distinction from both reactive and neoplastic salivary gland lesions such as sclerosing sialadenitis, polycystic dysgenetic disease, pleomorphic adenoma, cystadenocarcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and acinic cell carcinoma [5]. Atrophic and normal salivary acini may frequently occur between and in the lobules. Gnepp et al. [5] also showed two cases with a lipomatous stroma, as well as areas of reduplicated basement membrane-like material (collagenous spherulosis). A sparse to prominent chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate was invariably present. Occasional ducts may be denuded of epithelium and filled with xanthomatous macrophages.

There may be variable epithelial hyperplasia of the ducts and acini, with solid aggregates and intraluminal cribriform epithelial proliferation, areas of central necrosis, as well as prominent acinar proliferation and foci with adenosis that may mimic an acinic cell carcinoma. Gnepp et al. [5] cite ductal epithelial atypia, ranging from mild to severely atypical ductal epithelium to carcinoma in situ, to be about 56%. Our review of the reported cases with available clinical data showed variable degrees of ductal atypia and dysplasia in about 51.2% of cases. However, the lobular architecture was always maintained and there was no evidence of infiltration. The exact significance of the presence of epithelial dysplasia remains unclear. Malignant change of the dysplastic epithelium has yet to be demonstrated in SPA.

Histochemically, SPA is PAS positive with resistance to diastase digestion, but is non-reactive to mucicarmine and amylase. Immunophenotypically, the lesion is biphasic in nature, demonstrating both epithelial and myoepithelial cells. The luminal cells express AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, EMA, antimicrobial antibody, BRST-2 and S100-protein; focal oestrogen (5–20%) and progesterone (15–80%) receptor positivity, but not c-erbB2, p53, and CEA. The acinar cells are positive for GCDFP-15. Calponin, p63, anti-smooth muscle actin, muscle specific actin, S100 protein, and glial fibrillary acidic protein confirm the continuous abluminal myoepithelial layer, surrounding nearly every ductal and acinar structure [3, 12].

All reported cases of SPA were benign and cure was effected by localized surgical excision. Gnepp et al. [5] and Skálová et al. [6] have reported recurrence rates of about 19 and 30%, respectively, however our review has shown that thus far, 5 of 33 cases (15.2%) with specific follow up have recurred, including multiple recurrences over a period of 9 years [5]. Recurrence, however, appears to be due to inadequate surgical excision and to the multifocality of SPA as opposed to true recurrence. The outcome of SPA is favorable, with no reported metastases or deaths to date.

The etiology of SPA is still unknown. Although widely regarded as a pseudoneoplastic inflammatory sclerosing process, with low-grade neoplastic potential [5], the presence of dysplasia and recurrences prompted Skálová et al. [6] to investigate the clonal nature of SPA. Using the polymorphism of the human androgen receptor locus as a marker, they were able to demonstrate that SPA satisfied the criteria for monoclonality and concluded that SPA is likely to be a neoplasm and not just a reactive process. Whilst it is not unusual to find areas with a pseudoinfiltrative pattern of small ducts in the stroma similar to that seen in sclerosing adenosis of the breast, carcinomatous change within SPA has as yet not been reported.

Conclusion

Sclerosing polycystic adenosis is a benign entity with a positive outcome, which should be included in the working histopathologic differential diagnosis of both neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions of salivary gland, in order to differentiate this entity from other more clinically sinister salivary gland pathology.

References

- 1.Smith BC, Ellis GL, Slater LJ, et al. Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of major salivary glands: a clinicpathologic analysis of nine cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:161–70. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199602000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batsakis JG. Sclerosing polycystic adenosis: newly recognized salivary gland lesion—a form of chronic sialadenitis? Adv Anat Pathol. 1996;3:298–304. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skálová A, Michal M, Simpson RHW, et al. Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of parotid gland with dysplasia and ductal carcinoma in situ: report of three cases with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural examination. Virchows Arch. 2002;440:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s004280100481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imamura Y, Morishita T, Kawakami M, et al. Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the left parotid gland: report of a case with fine needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 2004;48:569–73. doi: 10.1159/000326420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gnepp DR, Wang LJ, Brandwein-Gensler M, et al. Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the salivary gland: a report of 16 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:154–64. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000186394.64840.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skálová A, Gnepp DR, Simpson RHW, et al. Clonal nature of sclerosing polycystic adenosis of salivary glands demonstrated by using the polymorphism of the human androgen receptor (HUMARA) locus as a marker. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:939–44. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200608000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noonan VL, Kalmar JR, Allen CM, et al. Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of minor salivary glands: report of three cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kloppenborg RP, Sepmeijer JW, Sie-Go DM, et al. Sclerosing polycystic adenosis: a case report. B-ENT. 2006;2:189–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bharadwaj G, Nawroz I, O'Regan B. Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the parotid gland. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;45:74–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Etit D, Pilch BZ, Osgood R, et al. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy findings in sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the parotid gland. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35:444–7. doi: 10.1002/dc.20671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gnepp D. Salivary and lacrimal glands. In: Gnepp DR, editor. Diagnostic surgical pathology of the head and neck. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 2001. pp. 349–50. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheuk W, Chan JK. Advances in salivary gland pathology. Histopathology. 2007;51:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]