Abstract

Background

The author analyzed social-status-specific differences in tobacco smoking, physical inactivity, and obesity among men and women aged 18 years and above in Germany.

Methods

The 2003 Telephone Health Survey carried out by the Robert Koch Institute from September 2002 to May 2003 (n = 8318) provided the data for this study. The subjects’ current smoking status, physical inactivity, and obesity were assessed. Their social status was judged on the basis of the information they gave about their education and professional training, occupational position, and net household income.

Results

Men of low social status were found to be more likely to smoke (OR = 1.89, 95% CI = 1.53–2.34), to be physically inactive (OR = 2.30, 95% CI = 1.87–2.84), and to be obese (OR = 1.34, 95% CI = 1.02–1.77) than men of high social status. For women, social status had just as large an effect on smoking and physical inactivity as it did in men (OR = 1.63, 95% CI = 1.30–2.09; and OR = 1.91, 95% CI = 1.58–2.33, respectively), while its effect on obesity was even greater than in men (OR = 3.20, 95% CI = 2.46–4.18).

Conclusion

These results imply that persons of low social status should be an important target group for preventive and health-promoting measures, both in health policy and in medical practice.

Numerous German and international studies indicate that the risk of illness and early death varies with social status and is highest among the lowest status groups (1– 4). The diseases and causes of death that are distributed unequally according to social status include coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, chronic bronchitis, liver cirrhosis, and certain forms of cancer, e.g., lung cancer and bowel cancer (5, 6). Many of these diseases are associated with risk factors that can be viewed in connection with the patient’s individual health behavior. Great importance is therefore attached to status-specific differences in health behavior in explaining unequal rates of illness and death. For instance, the World Health Organization (WHO) assumes that more than half of the social differences in early mortality among men in industrialized countries can be attributed to the higher rates of smoking in the low status groups (7). Other factors thought to be responsible for the increased risk of illness and death in segments of the population with low social status are the lower rates of participation in sports and physical activity in general and the higher frequency of overweight and especially obesity (8, 9).

In Germany, it was demonstrated empirically as early as the 1980s that persons of low social status smoke more commonly, have lower levels of physical and sporting activity, and are more often overweight or obese. Among other investigations, compelling findings emerged from the German Cardiovascular Prevention Study (Deutsche Herz-Kreislauf-Präventionsstudie, DHP) (10) and the MONICA Augsburg Study (11), both of which focused on cardiovascular diseases and risk factors. In recent years the nationwide health surveys conducted by the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) have played a leading role in providing robust basic data for analysis of the connection between social status and health and health behavior. Alongside the National Health Survey 1998 (12), the RKI’s 2003 Telephone Health Survey established interview of members of the population by telephone as an instrument of epidemiological research and health reporting in Germany (13).

This study uses the data of the 2003 Telephone Health Survey to investigate status-specific differences in the distribution of tobacco smoking, physical inactivity, and obesity among the adult German population. The analyses are intended to establish how pronounced these differences are and whether there are age- and sex-specific variations.

Methods

The RKI’s 2003 Telephone Health Survey was based on a randomly generated sample that at the time of sampling was representative of the adult (≥18 years) residential population of Germany. The sample comprised a compilation of private telephone numbers assembled according to the Gabler–Häder method and furnished by the Center for Surveys, Methods, and Analyses (Zentrum für Umfragen, Methoden, und Analysen, ZUMA). Between September 2002 and May 2003 a total of 8318 computer-assisted telephone interviews were carried out, corresponding to 59.2% of the sample (14).

The principal topics covered in the interview, which on average took 23 minutes to complete, included chronic diseases and symptoms, functional limitations, subjective health, health-related quality of life, health behavior, and utilization of health care services. For the purposes of this study, smokers were defined as persons who stated in the interview that they currently smoked cigarettes, cigars, a pipe, or another tobacco product, either regularly or occasionally. Physical inactivity was assumed if the interviewees stated that they had not participated in any sports in the previous 3 months. With regard to obesity, interviewees were asked their height and weight, from which the body mass index (BMI; weight in kg/height in m2) was calculated. Following WHO recommendations, persons with a BMI ≥30 were defined as obese.

Social status was determined on the basis of a multidimensional index (15). This index was calculated from interviewees’ information about their education and professional qualifications, their occupational position or that of their partner, and net household income (net income of all members of the household after tax and social contributions). The output variables, determined according to the recommendations of the German Working Group for Epidemiology (Deutsche Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Epidemiologie) (16), were transferred to ordinal scales, each with seven categories. These categories were assigned the values 1 to 7 and the total score was calculated. For the purposes of analysis three status groups were defined: 3 to 8 points, low social status; 9 to 14 points, intermediate social status; 15 to 21 points, high social status). Table 1 shows case numbers, frequency in the sample, and population for the central study variables.

Table 1. Descriptive data for the central study variables (n = 8318).

| Variable | Category | Number of cases (n) | Sample (%) | Population (%)* |

| Age | 18–39 years | 2923 | 35.1 | 37.4 |

| 40–59 years | 3436 | 41.3 | 33.0 | |

| 60+ years | 959 | 23.6 | 29.1 | |

| Sex | Men | 3872 | 46.5 | 48.3 |

| Women | 4446 | 53.5 | 51.7 | |

| Social status | Low | 1249 | 15.0 | 17.1 |

| Intermediate | 4381 | 52.7 | 54.0 | |

| High | 2546 | 30.6 | 28.9 | |

| Missing data | 142 | 1.7 | – | |

| Current smoker | Yes | 2818 | 33.9 | 32.5 |

| No | 5498 | 66.1 | 67.5 | |

| Missing data | 2 | 0.0 | – | |

| Physically inactive | Yes | 3027 | 36.4 | 37.9 |

| No | 5254 | 63.2 | 62.1 | |

| Missing data | 37 | 0.4 | – | |

| Obese (BMI ≥30) | Yes | 1469 | 17.7 | 18.5 |

| No | 6677 | 80.2 | 81.5 | |

| Missing data | 172 | 2.1 | – |

* Extrapolated to the adult (≥18 years) residential population at the time of sampling on December 31, 2001 (without missing data)

The results are presented separately for men and women and for three age groups: 18 to 39 years (young adults), 40 to 59 years (middle-aged), and 60 years or older (elderly). The cut-off points between these age groups were designed to provide sufficient cases for statistical analysis in each group. Besides prevalence, we report the results of binary logistic regressions (odds ratio, 95% confidence interval, p values, and Nagelkerke’s R2) with smoking, physical inactivity, or obesity as dependent variable and social status as independent variable. The odds ratios indicate by what factor smoking, physical inactivity, or obesity is more frequent in the low or intermediate status group than in the high status group, which serves as reference. As well as the effect of age, the influence of region of residence, immigration background, and presence of chronic illness was statistically controlled in the regression models. With regard to region of residence, the interviewees were divided into those living in the territories of the old West Germany and East Germany, with the whole of Berlin counted as part of the former. The immigration background category comprised immigrants and the children of immigrants. All those who stated in the interview that they suffered from one or more chronic diseases or health problems were defined as chronically ill.

Statistical analyses were carried out using the software package SPSS 17.0 on the basis of weighted data in order to obtain results representative of the reference population. The weighting factor was chosen to adapt the data to the age, sex, and regional residence distribution of the adult residential population at the time of sampling on 31 December 2001, based on the population statistics of the Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt) (14).

Results

In 2003, 32.5% of the adult (≥18 years) population of Germany were smokers. More men (37.3%) than women (28.0%) smoked. In both sexes the proportion of smokers decreased with increasing age. While 49.1% of 18- to 39-year-old men smoked, the rate was 38.1% in the 40- to 59-year olds and 18.2% in those aged 60 years or more. The corresponding smoking rates in women were 40.7%, 32.7%, and 10.2%.

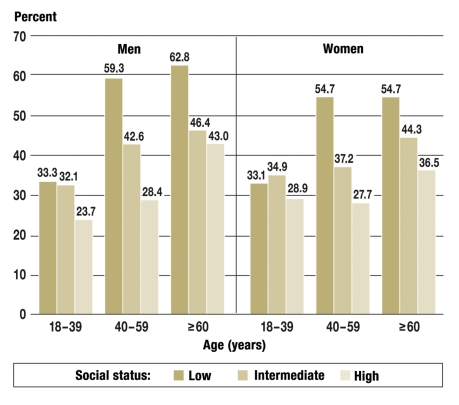

In all age groups the proportion of smokers varied with social status (figure 1). In young adults and the middle-aged more than half of the men with low social status smoked, compared with about a third of those with high social status. Among the elderly, too, more men of low social status smoked. A similar pattern could be discerned for women, although in the elderly the smoking rates were lower for women than for men over all social status groups.

Figure 1.

Proportions of male and female smokers in different age groups by social status

(n = 8174)

Overall, the proportion of the German adult population that did not participate in sports was 37.9% in 2003. The rates for men and women were similar: 37.4% and 38.4% respectively. For both sexes, the proportion of those who were physically inactive rose with age. Among the men, 30.0% of 18- to 39-year-olds, 38.0% of 40- to 59-year-olds, and as many as 47.9% of those aged 60 years or more did not take part in sports. The corresponding figures for women are 33.1% in young adults, 35.6% in middle age, and 46.6% in the elderly.

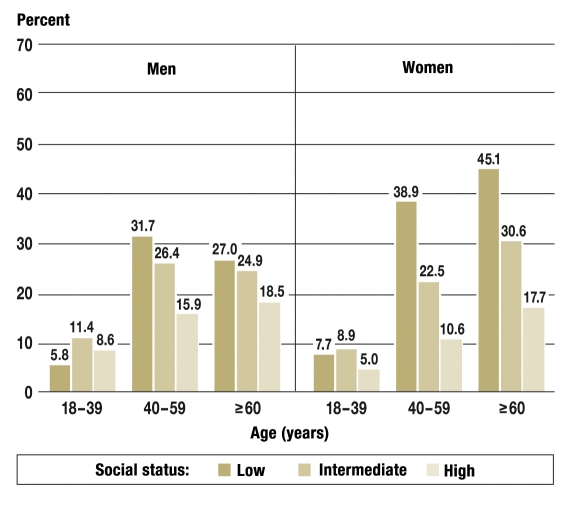

As with smoking, sporting activity showed distinct differences among the social status groups, to the disadvantage of the low status group (figure 2). This effect was most pronounced in the middle-aged and weaker for young adults and the elderly (Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Proportions of physically inactive men and women in different age groups by social status

(n = 8142)

Table 2. Smoking, physical inactivity, and obesity according to social status: results of binary logistic regression for men, controlling for the influence of age, immigration background, region of residence, and chronic illness.

| Smoking (n = 3800) | Physical inactivity (n = 3781) | Obesity (n = 3768) | ||||

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Men (18–39 years) | ||||||

| – Low social status | 1.70 [1.27–2.51] | p = 0.001 | 2.50 [1.72–3.65] | p < 0.001 | 1.26 [0.66–2.39] | p = 0.489 |

| – Intermediate social status | 1.94 [1.50–2.51] | p < 0.001 | 1.73 [1.29–2.31] | p < 0.001 | 1.72 [1.11–2.66] | p = 0.015 |

| – High social status | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Men (40 –59 years) | ||||||

| – Low social status | 2.76 [1.85–4.11] | p < 0.001 | 3.56 [2.37–5.33] | p < 0.001 | 2.39 [1.53–3.74] | p < 0.001 |

| – Intermediate social status | 1.53 [1.21–1.94] | p < 0.001 | 1.85 [1.46–2.35] | p < 0.001 | 1.88 [1.41–2.50] | p < 0.001 |

| – High social status | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Men (60+ years) | ||||||

| – Low social status | 2.97 [1.85–4.77] | p < 0.001 | 2.25 [1.50–3.34] | p < 0.001 | 1.60 [1.00–2.50] | p = 0.051 |

| – Intermediate social status | 1.27 [0.86–1.87] | p = 0.206 | 1.14 [0.86–1.51] | p = 0.365 | 1.41 [1.00–1.98] | p = 0.050 |

| – High social status | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Men (total) | ||||||

| – Low social status | 1.89 [1.53–2.34] | p < 0.001 | 2.30 [1.87–2.84] | p < 0.001 | 1.34 [1.02–1.77] | p = 0.039 |

| – Intermediate social status | 1.56 [1.33–1.82] | p < 0.001 | 1.54 [1.32–1.79] | p < 0.001 | 1.53 [1.26–1.85] | p < 0.001 |

| – High social status | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; Ref. = reference category; n = number of cases, based on non-age-differentiated model

Table 3. Smoking, physical inactivity, and obesity according to social status: results of binary logistic regression for women, controlling for the influence of age, immigration background, region of residence, and chronic illness.

| Smoking (n = 3800) | Physical inactivity (n = 3781) | Obesity (n = 3768) | ||||

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Women (18–39 years) | ||||||

| – Low social status | 2.74 [1.89–3.97] | p < 0.001 | 1.74 [1.19–2.54] | p = 0.004 | 3.27 [1.59–6.69] | p = 0.001 |

| – Intermediate social status | 2.22 [1.68–2.94] | p < 0.001 | 1.46 [1.46–1.92] | p = 0.008 | 2.20 [1.27–3.82] | p = 0.005 |

| – High social status | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Women (40–59 years) | ||||||

| – Low social status | 2.46 [1.89–3.97] | p < 0.001 | 3.12 [2.04–4.76] | p < 0.001 | 4.88 [2.96–8.03] | p < 0.001 |

| – Intermediate social status | 1.43 [1.10–1.85] | p = 0.007 | 1.52 [1.18–1.96] | p = 0.001 | 2.44 [1.71–3.48] | p < 0.001 |

| – High social status | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Women (60+ years) | ||||||

| – Low social status | 2.12 [1.13–4.00] | p = 0.020 | 2.00 [1.43–2.80] | p < 0.001 | 3.37 [2.27–5.02] | p < 0.001 |

| – Intermediate social status | 2.46 [1.37–4.42] | p = 0.003 | 1.40 [1.03–1.90] | p = 0.033 | 1.75 [1.20–2.54] | p = 0.004 |

| – High social status | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Women (total) | ||||||

| – Low social status | 1.63 [1.30–2.09] | p < 0.001 | 1.91 [1.58–2.33] | p < 0.001 | 3.20 [2.46–4.18] | p < 0.001 |

| – Intermediate social status | 1.67 [1.40–1.99] | p < 0.001 | 1.44 [1.23–1.69] | p < 0.001 | 2.00 [1.58–2.52] | p < 0.001 |

| – High social status | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; Ref. = reference category; n = number of cases, based on non-age-differentiated model

In 2003, 18.5% of the adult population of Germany were obese. The prevalence was slightly lower for men (17.3%) than for women (19.7%). The proportion of obese men and women rose clearly with age. Among the men, 9.4% of 18- to 39-year-olds were obese, compared with 22.3% of 40- to 59-year-olds and 22.8% of those aged 60 years or more. For female young adults (7.7%) and middle-aged women (19.8%) the rates of obesity were similar to those in men. Among elderly women 32.8% were obese, a much higher rate than in men of the same age group.

Men of low social status had a distinctly higher frequency of obesity in middle age and a slightly higher prevalence among the elderly (figure 3). Among young adult men the highest rate of obesity was found in the intermediate status group. In women the status-specific differences in prevalence of obesity were even more pronounced than in men. The differences were particularly great in the middle-aged and elderly, but attained statistical significance even in young adults (table 3).

Figure 3.

Proportions of obese men and women in different age groups by social status

(n = 8142)

The multivariate analyses substantiated the descriptive findings. Controlling for age, region of residence, immigration background, and chronic illness, the odds of smoking in the low status group, relative to the high status group, was 1.9 times higher for male adults and 1.6 times higher for females (Tables 2 and 3). In the intermediate status group, too, the odds of smoking were higher for both sexes than in the high status group. With regard to age, the status-specific differences were greater for middle-aged and elderly men than for male young adults. For women the status-specific differences were similarly pronounced in all age groups.

Furthermore, the multivariate analyses revealed that compared with men from the high status group, those from the low status group were less likely to be physically active by a factor of 2.3. The corresponding factor for women was 1.9 : 1. For both sexes, these status-specific differences were greatest among the middle-aged. The members of the intermediate status group also had a greater chance of being physically inactive relative to the high status group. Only in men aged 60 years or more were there no differences among the status groups with regard to sporting activity.

The results for obesity showed a difference between the sexes. Men in the low status group had only a slightly increased chance relative to the high status group. The differences were not statistically significant in 18- to 39-year-old males; however, men from the intermediate status group had a significantly higher chance than those in the high status group of being obese. Women, in contrast, displayed a steep status gradient in all age groups. The difference was most pronounced among 40- to 59-year-olds, where women from the low status group had a 4.9 times greater chance of being obese than those from the high status group.

When evaluating the results it must be recognized that social status explains only a relatively small proportion of the variance of the risk factors considered. With Nagelkerke’s R2 as measure of the model’s goodness of fit, no more than 6% of the variance is explained in relation to smoking, physical inactivity, and obesity. Inclusion of the other study variables (age, region of residence, immigration background, chronic illness) improves the fit. The highest explanation of variance, 17%, is attained for the incidence of obesity in women.

Discussion

The results of the 2003 Telephone Health Survey point to distinct status-specific differences in the incidence of smoking, physical inactivity, and obesity. These differences can be described as a gradient: the lower the social status, the higher the chance of being a smoker, physically inactive, or obese. This gradient is steepest in middle age, but also noticeable in young adults and the elderly.

When considering the results it must be borne in mind that the study was based on self-reports and thus the incidence of the risks in question could be underestimated. With regard to obesity, for instance, the participants in the German Cardiovascular Prevention Study tended to overestimate their height and underestimate their weight, with the result that the BMI calculated from the self-reported data was somewhat lower than the reference value obtained from measurements (17). In addition, some interviewees’ responses regarding smoking and sporting activity were feasibly affected by social expectations. It is a weakness of the present study, moreover, that physical inactivity could not be recorded with any precision. Equally, the data of the 2003 Telephone Health Survey do not permit any conclusions about physical activity in the daily routine and during leisure time and thus paint only a partial picture of the respondents’ exercise behavior.

Comparison with the findings of earlier research indicates that the status-specific differences in the incidence of risk factors have not become any smaller. Both the German Cardiovascular Prevention Study and the MONICA Augsburg study showed that relative to those of high social status, persons of low social status were more likely, by factors of 1.5 to 3, to be smokers, physically inactive, or obese (9, 18). The 1998 National Health Survey found similarly pronounced status-specific differences with regard to risk factors (19). Investigators in some other countries have even reported increased social disparity in the incidence of smoking, physical inactivity, and obesity over the past 20 years. Particularly striking are the findings regarding smoking in Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Italy, and Spain (20).

As far as doctors are concerned, the findings regarding smoking, physical inactivity, and obesity strongly suggest that they should address these risk factors directly and advise their patients of the potential consequences for their health (21– 23). Recommendations as to behavior modification and potential treatment approaches should take into account each patient’s individual circumstances with regard to family, work, and other areas of life. Consideration of the patient’s attitude, motivation, and resources for change, all of which are intimately connected with their life circumstances and social status, is also crucial to the success of any medical recommendations.

Effective reduction of health inequality can probably be achieved only by means of a comprehensive political strategy embracing not only health policy but also other areas, such as social, family, education, and employment policies. Strategies of this nature have been pursued for some years in countries such as Great Britain, Sweden, and Norway, in some cases with concrete targets, but there is no counterpart in Germany (24).

Key Messages.

Smoking, physical inactivity, and obesity remain extremely common in the general population.

These risk factors are more frequent in persons of low and intermediate social status than in those of high social status.

Because of their links with many chronic diseases, the risk factors are associated with considerable potential for prevention and cost reduction.

Prevention of the risk factors should form a central plank of medical practice.

Effective reduction of the status-specific differences in the incidence of the risk factors requires a comprehensive political strategy.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The author declares that no conflict of interest exists according to the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJR. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 Euopean countries. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;358:2468–2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365:1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huisman M, Kunst A, Andersen O, et al. Socio-economic inequalities in mortality among elderly people in 11 European populations. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2004;58:468–475. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.010496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein T, Schneider S, Löwel H. Bildung und Mortalität. Die Bedeutung gesundheitsrelevanter Aspekte des Lebensstils. Zeitschrift für Soziologie. 2001;30:384–400. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith Davey G, Gunnel D, Ben-Shlomo Y. Life-course approaches to socioeconomic differentials in cause-specific adult mortallity. In: Leon D, Poverty WG, editors. Inequality and health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 88–124. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalstra JAA, Kunst AE, Borrell C, et al. Socioeconomic differences in the prevalence of common chronic diseases: an overview of eight European countries. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;34:316–326. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bobak M, Jha P, Nguyen S, et al. Poverty and smoking. In: Jha P, Chaloupka FJ, editors. Tobacco control in developing countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adler NE, Ostrove JM. Socioeonomic status and health: What we know and what we don’t know. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 1999;896:3–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helmert U. Soziale Ungleichheit und Krankheitsrisiken. Augsburg: Maro Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forschungsverbund DHP (eds.) Design und Ergebnisse. Bern, Göttingen, Toronto, Seattle: Verlag Hans Huber; 1998. Die Deutsche Herz-Kreislauf–Präventionsstudie. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keil U. Das weltweite WHO-MONICA-Projekt: Ergebnisse und Ausblick. Gesundheitswesen. 2005;67(Sonderheft 1):38–45. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellach BM, Knopf H, Thefeld W. Der Bundes-Gesundheitssurvey 1997/98. Das Gesundheitswesen. 1999;60(Sonderheft 2):59–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziese T, Neuhauser H. Der telefonische Gesundheitssurvey 2003 als Instrument der Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz. 2005;48:1211–1216. doi: 10.1007/s00103-005-1159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohler M, Rieck A, Borch S. Methodische Aspekte des telefonischen Gesundheitssurvey 2003. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz. 2005;48:1224–1230. doi: 10.1007/s00103-005-1154-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winkler G, Stolzenberg H. Der Sozialstatusindex im Bundes-Gesundheitssurvey. Gesundheitswesen. 1999;61(Sonderheft 2):178–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jöckel KH, Babitsch B, Bellach BM, et al. Messung und Quantifizierung soziodemographischer Merkmale in epidemiologischen Studien. RKI-Schriften. 1998;1:7–38. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mensink GBM, Lampert T, Bergmann E. Übergewicht und Adipositas in Deutschland 1984-2003. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz. 2005;48:1348–1356. doi: 10.1007/s00103-005-1163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Härtel U, Stieber J, Keil U. Der Einfluss von Ausbildung und beruf-licher Position auf Veränderungen im Zigarettenrauchen und Alkoholkonsum: Ergebnisse der MONICA Augsburg Kohortenstudie. Sozial- und Präventivmedizin. 1993;38:133–141. doi: 10.1007/BF01324346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lampert T, Thamm M. Soziale Ungleichheit des Rauchverhaltens in Deutschland. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz. 2004;47:1033–1042. doi: 10.1007/s00103-004-0934-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giskes K, Kunst AE, Benach J, et al. Trends in smoking behaviour between 1985 and 2000 in nine European countries by education. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005;59:395–401. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.025684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lampert T. Smoking and passive smoking exposure in young people—results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS) Dtsch. Arztebl Int. 2008;105(15):265–271. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurth BM, Ellert U. Perceived or True Obesity: Which Causes More Suffering in Adolescents? Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105(23):406–412. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leyk D, Rüther T, Wunderlich M, et al. Sporting activity, prevalence of overweight, and risk factors—cross-sectional study of more than 12 500 participants aged 16 to 25 years. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105(46):793–800. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mielck A. Quantitative Zielvorgaben zur Verringerung der gesundheitlichen Ungleichheit: Lernen von anderen westeuropäischen Staaten. In: Richter M, Hurrelmann K, editors. Gesundheitliche Ungleichheit. Grundlagen, Probleme, Konzepte. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2006. pp. 439–451. [Google Scholar]