Abstract

Background

Although the incidence of tuberculosis (TB) in Germany is now declining, the world as a whole faces the threat of a catastrophe that will also affect the industrialized nations. The main reason, aside from TB/HIV co-infection, is the increase of resistant TB strains. The situation is already serious because of the spread of multidrug-resistant TB, i.e., TB that is resistant to the two most important antituberculous drugs, and is being further aggravated by resistance to second-line drugs as well.

Method

Selective review of the literature.

Results

There are an estimated half a million cases of multidrug-resistant TB worldwide, and so-called extensively resistant TB (XDR-TB), with additional resistance to defined second-line drugs, is now prevalent in more than 45 countries. An accurate assessment of the situation is hampered by a widespread lack of laboratory capacity and/or proper surveillance. The problem is mainly due to inappropriate treatment, which may have many causes, but is theoretically avoidable. Aside from programmatic weaknesses, a lack of diagnostic and therapeutic tools causes difficulties in many countries.

Discussion

Only rapid and internationally concerted action, combined with intensified research efforts and the support of the affected nations, will be able to prevent the development of a situation that will no longer be manageable even with 21st-century technology.

In early 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported an unexpectedly large increase in the number of cases of drug-resistant tuberculosis (1). At present, an estimated 5% of the more than 9 million persons who develop tuberculosis (TB) around the world every year are infected with a multi-resistant strain of tuberculosis (multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, MDR-TB), i.e., a strain that is resistant to (at least) the two most powerful anti-tuberculosis drugs that are currently available, isoniazid and rifampicin. The current WHO report (1) also contains data on extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB), which was first described in 2006. By definition, XDR-TB is MDR-TB that is additionally resistant to at least one of the fluoroquinolones and to one of the three injectable second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs, amikacin, kanamycin, and capreomycin (2, e1).

In the 1970’s, TB was thought to have been nearly vanquished, yet it is now the most deadly bacterial (and curable) infectious disease around the world. The main reason for this is co-infection with tuberculosis and HIV, a condition that is most common in sub-Saharan Africa but is also on the rise in other regions of the world, including Europe (e2).

Despite positive epidemiological developments in Germany, the effects of the worldwide trend are making themselves felt here as well, as half of the tuberculosis patients in Germany were born abroad (3, e3).

This article is based on a selective review of the literature.

Its learning objectives for readers are

to obtain insight into the problem of resistance development in tuberculosis;

to master the fundamentals of the diagnosis and treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis;

to be able to assess epidemiological developments in this area.

Epidemiology.

It is estimated that, at present, 5% of the more than 9 million persons who develop tuberculosis around the world every year are infected with a multidrug-resistant strain of tuberculosis.

Epidemiological developments

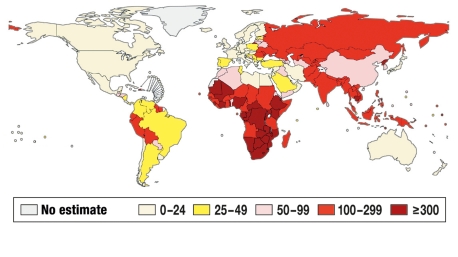

The WHO estimates that there were 9.27 million new cases of tuberculosis and 1.78 million deaths from tuberculosis worldwide in 2007 (4). Figure 1 shows the regional incidences of tuberculosis, while Table 1 contains statistics on the 22 “high-burden” countries (1, 4).

Figure 1.

WHO estimates of the incidence of tuberculosis (all types) per 100 000 population per year in the world population for the year 2007, reprinted with the kind permission of the WHO (modified from [4]).

Table 1. 22 high-burden countries*1.

| Country | Incidence of TB (all types) per 100,000 population | Mortality per 100,000 population | HIV prevalence in incident TB cases, in % | MDR in new cases, in % |

| South Africa | 948 | 230 | 73 | 1.8 |

| Zimbabwe | 782 | 265 | 69 | 1.9 |

| Cambodia | 495 | 89 | 7.8 | <0.05 |

| Mozambique | 431 | 127 | 47 | 3.5 |

| DR Congo | 392 | 82 | 5.9 | 2.3 |

| Kenya | 353 | 65 | 48 | 1.9 |

| Ethiopia | 378 | 92 | 19 | 1.6 |

| Uganda | 330 | 93 | 39 | 0.5 |

| UR Tanzania | 297 | 78 | 47 | 1.1 |

| Nigeria | 311 | 93 | 27 | 1.8 |

| Philippines | 290 | 41 | 0.3 | 4.0 |

| Indonesia | 228 | 39 | 3.0 | 2.0 |

| Bangladesh | 223 | 45 | 0 | 3.5 |

| Pakistan | 181 | 29 | 2.1 | 3.2 |

| Vietnam | 171 | 24 | 8.1 | 2.7 |

| Myanmar | 171 | 13 | 11 | 4.0 |

| India | 168 | 28 | 5.3 | 2.8 |

| Afghanistan | 168 | 30 | <0.05 | 3.3 |

| Thailand | 142 | 21 | 17 | 1.7 |

| Russ. Federation | 110 | 18 | 16 | 13 |

| China | 98 | 15 | 1.9 | 5.0 |

| Brazil | 48 | 4 | 14 | 0.9 |

*1 WHO estimates of the incidence and mortality of TB per 100 000 population (all types), of the prevalence of HIV in incident TB cases, and of the MDR rate among new cases in the year 2007 (4); H, isoniazid; R, rifampicin; E, ethambutol; S, streptomycin; MDR, multidrug resistance, i.e., resistance to (at least) isoniazid and rifampicin

In the WHO European region—a geographical region defined by the WHO, consisting of 53 countries—nearly 500 000 new cases of tuberculosis were registered in 2006, with a clear east-west gradient: the incidence ranged from 282 per 100 000 population in Kazakhstan to 5.5 per 100 000 population in Sweden (e4).

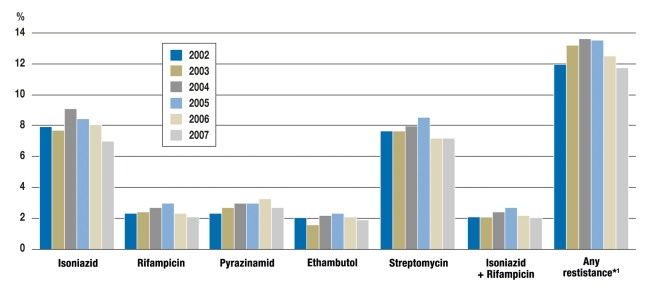

Germany, with 6.1 new cases of tuberculosis per 100 000 population per year (2007; n = 5020), is one of the low-incidence countries, with a mortality rate of 0.2/100 000 (3). 43% of these patients were born outside the country. In 2007, the incidence of tuberculosis among citizens of foreign countries living in Germany was five times that among German citizens (22.8 versus 4.2 per 100 000 population) (3). Resistance rates rose slightly from 2001 to 2005, then fell again somewhat in 2006 and 2007, perhaps because of a decline in immigration, especially from the newly independent countries that formerly belonged to the Soviet Union (3) (figure 2). Among patients from these countries, the rate of MDR was 12.8%, and that of “any drug resistance” (i.e., resistance to any one of the five standard drugs) was 34.6%; the corresponding figures for persons born in Germany were 0.6% and 7.5%, respectively (3). 53 of the 66 patients diagnosed with MDR tuberculosis in 2007 were born outside of the country, 38 of them in countries that formerly belonged to the Soviet Union (3). Precise data on XDR tuberculosis are not available, because findings regarding resistance to second-line drugs are not routinely reported; XDR is thought to account for fewer than 5% of MDR cases (5, e5, e6).

Figure 2.

The development of resistance to the five first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs used in Germany from 2002 to 2007; resistance rates in percent (according to [3]).

From 2001 onward, the resistance test results were entered into a registry as required by the German Infection Protection Act. The numbers of bacterial strains tested were: 4691in 2002, 4464 in 2003, 4067 in 2004, 3886 in 2005, 3618 in 2006, and 3242 in 2007;

*1 Resistance to any one of the first-line drugs isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, and streptomycin

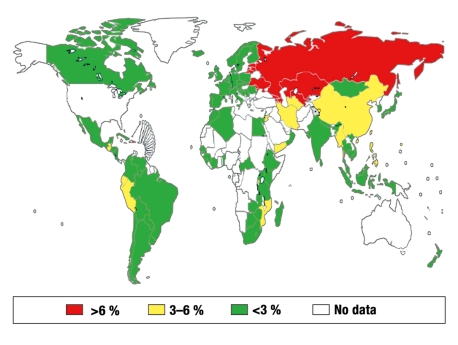

Resistance to anti-tuberculosis drugs has been observed around the world, yet valid and comprehensive data are often unavailable (2, 6, e7). Data from 116 countries and regions for the year 2006 (2 509 545 tuberculosis patients) (1) yield a 2.9% rate of MDR tuberculosis among new cases of the disease (figure 3) and a 15.3% rate among persons who have received at least one month of treatment for tuberculosis. The “combined” resistance rate of 5.3% corresponds to nearly half a million patients with MDR tuberculosis around the world.

Figure 3.

The estimated percentage of multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis in newly diagnosed and not previously treated tuberculosis patients worldwide, by region, from 1994 to 2007 (overall percentage, 2.9%); reprinted with the kind permission of the WHO (modified from [1])

Incidence.

Germany is a low-incidence country, with 6.1 new cases per 100 000 population per year.

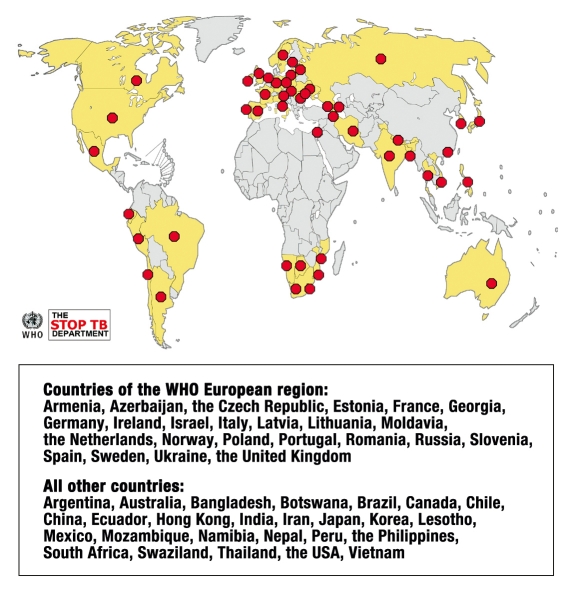

Data on resistance to second-line drugs in the year 2006 were collected from international reference laboratories in 49 countries. Among 17 000 bacterial isolates, the rate of MDR was 20% and that of extensive resistance was 2% (e8), although selection bias cannot be excluded. The percentage of XDR varies markedly; it is currently highest in Estonia, at 24% (1). XDR tuberculosis had been diagnosed in 45 countries by June 2008 (efigure). Tuberculosis with extremely extensive resistance (XXDR tuberculosis), i.e., resistance to practically all of the anti-tuberculosis drugs, has been seen in only a few cases to date (e9).

eFigure.

45 countries with confirmed cases of XDR tuberculosis (by February 2008; the number rose to 55 countries by the end of 2008). Each red point stands for a country in which XDR tuberculosis has been detected. Reprinted with kind permission of the WHO

Reasons for the development of resistance

Impressive therapeutic outcomes were seen when streptomycin, the first anti-tuberculosis drug, was introduced in 1944. There were, however, many recurrences of tuberculosis thereafter, because of the selection of streptomycin-resistant bacterial strains by monotherapy (e10, e11). The more widespread tuberculosis is in the patient’s body, the greater the number of bacteria that are present, and the more likely it is that some of the pathogenic organisms will contain spontaneous mutations conferring drug resistance (e12).

The need for combination therapy against tuberculosis was recognized after the introduction of para-aminosalicylic acid in 1944 and that of isoniazid in 1952 (e13), as the rate of mutations conferring resistance to multiple drugs is very low. Furthermore, combination therapy can better reach bacteria with different levels of metabolic activity at multiple sites in the body. The treatment must be continued long enough to kill quiescent bacteria (“dormant persisters”) as well.

Causes of the development of resistance.

Monotherapy promotes the selection of bacterial strains that are already resistant.

The next drugs to be introduced were pyrazinamide and cycloserine in 1952, capreomycin in 1960, ethambutol in 1961, and rifampicin in 1966. The introduction of rifampicin and pyrazinamide enabled a marked shortening of the duration of therapy, from 18–24 to 6 months (“short-term chemotherapy”), provided that the patient’s tuberculosis is fully drug-sensitive. The recurrence rate after such treatment is less than 5% in patients who take all their medications correctly every day as prescribed (e13).

Faulty prescriptions, treatment compliance problems, inadequate intestinal resorption of drugs, and poor drug quality are factors that can promote the development of resistance (1, 2).

The risk factors for MDR tuberculosis are.

prior anti-tuberculosis treatment

immigration from a region with a high prevalence of MDR tuberculosis

contact with MDR tuberculosis patients

imprisonment

Drug resistance was first recognized as a major problem in 1992, when 12% of the tuberculosis patients in New York City were found to have MDR tuberculosis (e14). MDR tuberculosis spread around the world (1) because of the lack or inadequacy of tuberculosis control programs, insufficient resources, and inadequate protective measures against infection, as well as delayed diagnosis of tuberculosis (7).

The following are special risk factors for MDR tuberculosis:

prior treatment with anti-tuberculosis drugs

immigration from an area where MDR tuberculosis is highly prevalent, or contact with MDR tuberculosis patients

imprisonment

Prisons require special attention, particularly in the Newly Independent States of the former Soviet Union (9). In the WHO European region, the mean case-reporting rate for tuberculosis among prisoners is 232 per 100 000 population, while the country-specific rates are highest in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, at 17,808 and 3944 per 100 000 population, respectively (e15). Even though there is a downward trend in some countries (Russian Federation, 1999–2005: from 4000 to 1591 cases per 100 000 population), the high rates of MDR—sometimes accounting for more than 30% of overall incidence—and the rising prevalence of HIV are causes for concern (9). Prisoners have been found to have higher rates of MDR in Western, industrialized countries as well (e15, e17).

In some regions of the world, the so-called Beijing genotype of Mycobacterium (M.) tuberculosis is associated with a high resistance rate and, in particular, with a high MDR rate (the “W strain”) (e18). These strains may be more virulent, and/or more likely to mutate, and/or able to spread more easily because of poorer tuberculosis control in the areas to which they are endemic.

Resistant tuberculosis and co-infection with HIV

It is estimated that, in 2007, 1.37 of the 9.27 million persons with new tuberculosis infections were co-infected with HIV (14.8%), and 456 000 persons died of tuberculosis in the presence of an HIV infection (4). In some countries of sub-Saharan Africa, the tuberculosis/HIV co-infection rate has risen dramatically, to 50–80% (4, 10, e19). HIV-positive persons carrying a latent M. tuberculosis infection are at markedly higher risk of developing tuberculosis (10). Next to malaria, tuberculosis and HIV are the deadliest infectious diseases worldwide, and tuberculosis is one of the main causes of death in HIV-infected persons (10, e20). It is unclear whether HIV infection is a risk factor for drug-resistant or multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (1, 6, 8). Higher resistance rates might be explicable as the result of higher susceptibility to resistant bacterial strains, which are often less virulent than non-resistant strains, as well as of the higher percentage of new infections (8). Other factors that can promote the development of resistance include malabsorption, drug intolerance, drug interactions, and noncompliance among IV drug abusers (8). Hospitalization also increases the risk of exposure (6, e16). There was a catastrophic development in South Africa in 2006, when XDR tuberculosis was transmitted from infected patients to members of a village community with a high prevalence of HIV. The affected patients were hospitalized, whereupon a large number of patients and hospital employees died within a few weeks (11). The main causes for the persistent transmission of XDR-TB in South Africa are, aside from the high prevalence of HIV, delays in diagnosis and treatment and the inadequate availability of modern diagnostic procedures, second-line drugs, and precautions against infection.

HIV and tuberculosis.

After malaria, tuberculosis and HIV are the infectious diseases causing the greatest number of deaths worldwide.

Factors promoting the development of resistance.

Malabsorption, drug intolerance, and drug interactions can promote the development of resistance.

High-burden countries.

South Africa and Zimbabwe have the highest incidence, mortality, and HIV/TB co-infection rates among the 22 high-burden countries.

Another current cause for concern is the rising rate of HIV infection in Eastern Europe, particularly in the Russian Federation and the Ukraine (e2, e21). Prisons in these countries are high-risk areas for dual infections because of an increasing rate of IV drug abuse, combined with a high prevalence of MDR tuberculosis (e21).

There are no reliable figures on the rate of tuberculosis/HIV co-infection in Germany, because HIV infection is reported anonymously. The co-infection rate is estimated to be below 5% (5, e2, e22).

When drug-resistant tuberculosis is suspected.

The suspicion of tuberculosis can be definitively confirmed only with the aid of standardized, quality-controlled bacteriological sensitivity testing.

The diagnosis of drug-resistant tuberculosis

Drug resistance is suspected when one or more of the risk factors discussed above are present. It can be definitively confirmed only with the aid of standardized, quality-controlled bacteriological sensitivity testing. Because directed therapy is possible only on the basis of the resistance findings, bacteriological proof of tuberculosis infection should always be attempted, even in types of pulmonary or extrapulmonary infection where relatively few bacteria are present.

The gold standard is resistance testing with culture techniques; such testing previously took eight to twelve weeks, but its duration has been shortened recently to two to three weeks with the aid of liquid cultures and radiometric methods (12). More rapid molecular biological methods for the detection of genetic mutations that confer resistance to various drugs (rifampicin, isoniazid) are an outstanding recent advance in this area (12, e23, e24). Microscopic observation of drug susceptibility (MODS) is one of several promising new techniques (e5, e23, e25).

The gold standard of resistance testing.

Resistance testing with culture techniques remains the gold standard for the diagnostic evaluation of tuberculosis.

Resistance testing for second-line drugs is highly demanding and requires the expertise of specialized laboratories (2). Moreover, in vitro results often do not accurately reflect actual drug efficacy (2). A rapid test for tuberculosis that could be performed directly on a sputum sample, with which the pathogens could be simultaneously detected and comprehensively tested for resistance, would certainly be a milestone in the fight against tuberculosis (e5, e25, e26).

The treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis

Tuberculosis must be treated with a combination of antibiotics (e13). The currently recommended standard chemotherapy of non-resistant tuberculosis consists of the initial administration of four first-line drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol or streptomycin) in combination for two months, followed by a four-month stabilization phase with a combination of isoniazid and rifampicin (13, e27).

Sensitivity testing should be performed as rapidly as possible, particularly when drug resistance is suspected, so that the development of further resistance will not be promoted by nonspecific therapy (e28). A single drug should never be added to an existing regimen, as this creates the danger of monotherapy (2).

No randomized trials or evidence-based data are available on the treatment of resistant tuberculosis (14, e5). The WHO recommends that patients who were previously treated for tuberculosis should be treated with at least three drugs that they have not received before. When multiple resistance is suspected, at least four drugs that are still potentially effective should be given (2). As a rule, complex cases of resistant tuberculosis should be treated by physicians with special experience in this area.

The new WHO classification of first- and second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs is shown in Table 2. The fluoroquinolones are among the main types of second-line drug. In Germany, linezolid is often given in cases with complex resistance patterns (5), even though it has not been recommended by the WHO for routine use. It should be used only in specifically chosen, individual cases, in view of its potential toxicity (5)—in particular, marked changes in blood counts and peripheral polyneuropathy—and high cost.

Table 2. New WHO classification of anti-tuberculosis drugs (2).

| Group | Description | Substance/medication | International abbreviation |

| 1 | Oral first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs | Isoniazid | H |

| Rifampicin | R | ||

| Ethambutol | E | ||

| Pyrazinamide | Z | ||

| Rifabutin | Rfb | ||

| 2 | Injectable anti-tuberculosis drugs | Kanamycin | Km |

| Amikacin | Amk | ||

| Capreomycin | Cm | ||

| Streptomycin | S | ||

| 3 | Fluoroquinolones | Levofloxacin | Lfx |

| Moxifloxacin | Mfx | ||

| Ofloxacin | Ofx | ||

| 4 | Oral second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs | Ethionamide | Eto |

| Protionamide | Pto | ||

| Cycloserine | Cs | ||

| Terizidone | Trd | ||

| P-aminosalicylic acid | PAS | ||

| 5 | Anti-tuberculosis drugs with unclear effectiveness and/or an unclear role in the treatment of MDR-TB (not recommended by the WHO for routine use) | Clofazimine | Cfz |

| Linezolid | Lzd | ||

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | Amx/Clv | ||

| Thiocetazone | Thz | ||

| Clarithromycin | Clr | ||

| Imipenem | Ipm |

The treatment takes up to two years and is often poorly tolerated. It thus requires a high degree of patient cooperation, and the rate of premature termination of treatment is higher than in non-resistant tuberculosis (up to 30%) (e5, e29). Thus, extensive patient education is needed, and the patient should take the medications under professional supervision, if possible. The possibility of contagion necessitates adequate preventive measures against infection. Patients who are unwilling or unable to comply with such measures may need to be involuntarily quarantined; such decisions are to be taken on a case-by-case basis (15).

The treatment of non-resistant tuberculosis.

Standard chemotherapy consists of the initial administration of a combination of four first-line drugs for two months, followed by a four-month stabilization phase with isoniazid and rifampicin.

The success rate of treatment is lower for MDR tuberculosis than for less resistant or non-resistant tuberculosis, and it is lower still for XDR tuberculosis (2, 5, 11, 15– 17, e5, e30). The Robert Koch Institute reports a current 52% cure rate for MDR tuberculosis (3). This figure accords well with other figures on the same subject from Germany (5, e22) and other countries (14, 17, e5, e31– e33).

The relevant percentage of patients whose therapeutic outcome is unknown, or whose treatment has not yet been completed, can substantially diminish the success rate, depending on how this rate is defined (5). Furthermore, the therapeutic outcome may be difficult to categorize: for example, when the treatment has been changed or interrupted for a long time (e34). Nonetheless, effective surveillance of resistance findings and therapeutic outcomes is very important if the quality of tuberculosis control is to be accurately judged (3).

Treatment tolerance.

In the presence of antibiotic resistance, the treatment may last up to two years and is often poorly tolerated. It requires a high degree of patient cooperation. Thus, extensive patient education and counseling are needed.

No official statistics are available on therapeutic outcomes for XDR tuberculosis in Germany, but studies of the relevant data have revealed, in accordance with international studies (17, 18, e5, e31, e35), that the outcomes are worse than in MDR tuberculosis, with markedly longer duration of illness and hospitalization, delayed bacteriological conversion, and higher cost (5, 15, e6). Seven patients treated for XDR tuberculosis in Germany had, in comparison to 177 patients with MDR tuberculosis, both a longer duration of hospital stay (202 vs 162 days) and a longer time to conversion of sputum cultures (141 vs 82 days), and these differences were statistically significant (5). The mean duration of treatment in four patients treated for XDR tuberculosis was 2.2 years (15). When previous treatments before the diagnosis of XDR tuberculosis were also taken into account, the duration of hospitalization in these patients (among whom compliance was also a major problem) ranged from eleven months to six years.

Supportive therapeutic measures.

Improved nutrition and improvement of the patient’s social environment are among the most important interventions that can supplement drug therapy for tuberculosis.

Improved nutrition and improvement of the patient’s social environment are among the most important interventions that can supplement drug therapy for tuberculosis (2, 14). Operative treatment, in addition to drug therapy, is indicated in cases of MDR or XDR tuberculosis if not enough medications are available, and also in cases of non-conversion of serum cultures, persistent caverns, and/or mainly localized disease, as long as there are no functional contraindications to surgery (14, 16). Good results have been described, but often with quite high complication rates (14, 16, 18, e35). There have been no controlled trials on this subject; it seems likely that the operability criteria that were applied led to a selection of prognostically more favorable cases.

The cost of treatment in cases with complex drug resistance is several times higher than that of drug-sensitive tuberculosis (e8, e36). Moreover, the indirect costs, including that of prolonged inability to work, are often substantial. When these costs are taken into account, the cost of some cases of MDR tuberculosis in the USA is found to be in excess of one million dollars (e37). The cost of treating XDR tuberculosis is even higher. In Germany, the direct medical cost of two years of treatment for XDR tuberculosis alone amounts to 170 000 euros (15).

Strategies against drug resistance

In 2006, the WHO announced an ambitious global plan to lower the rate of new infections with tuberculosis and the death rate from tuberculosis to half of their 1990 levels by the year 2015 (19). A further goal is the eradication of the disease by the year 2050, i.e., lowering its incidence to less than one new case of tuberculosis per one million population per year. The overall financing plan envisions 56 billion dollars of financial support for the period 2006–2015 (20). More than one billion dollars are budgeted for the successful treatment of MDR and XDR tuberculosis cases in the year 2009 alone, in addition to the necessary overall expenditures for global tuberculosis control, which amount to 5.3 billion dollars. A basic prerequisite for the prevention of drug-resistant tuberculosis is adherence to the stated principles of treatment, in the setting of an effective national tuberculosis control program, whenever possible (7, 21, 22). The DOTS strategy (Directly Observed Treatment Short Course”) is recommended for implementation (19); in recognition of the problem of resistance, the DOTS strategy has been extended to the so-called DOTS-plus strategy, and to other action plans that build upon it (22, 23, e8, e38– e39). The implementation of these plans is difficult, however, not just because of inadequate financial means, but often also because the necessary infrastructure is lacking, e.g., adequately trained personnel.

Indications for surgery.

Surgical treatment, in addition to medical treatment, is indicated only for selected, individual patients, e.g., those with persistent caverns.

The Green Light Committee established by the WHO provides technical support to poorer countries and negotiates reduced prices for quality-controlled second-line drugs. A functioning national tuberculosis control program is a prerequisite (e40).

It is currently debated whether standardized treatment regimens for non-responders to therapy (e27) should be replaced by individualized regimens based on (rapid) resistance testing (e5, e7, e24, e41) in regions of the world where MDR tuberculosis is highly prevalent.

Research also needs to be substantially intensified in this area (21, e42). Alongside better diagnostic techniques for tuberculosis, including techniques for the determination of drug resistance, there is an urgent need for the development (or further development) and testing of highly effective anti-tuberculosis drugs (24). Over the long term, there are high hopes that effective vaccines can be developed through the improvement, supplementation, or replacement of BCG (Bacille Calmette-Guérin), a vaccine based on an attenuated strain of M. bovis (25).

The “Global Stop TB Partnership” (e43), founded in 2000 and now with more than 700 private and governmental partners, serves to merge common interests and capabilities. It receives major financial support from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (e44), as well as other organizations.

All of these approaches need to be continuously maintained and vigorously supported. Even in a country like Germany, in which there are adequate high-quality laboratory services and all second-line drugs are available, success rates in the treatment of MDR and XDR tuberculosis remain unsatisfactory (3, 5, 15). It follows that the worsening resistance situation all over the world can only be combated and alleviated through a common effort (7, 21, e38, e39). The political will of the industrialized countries and their assumption of responsibility for health policy, which were expressed in a declaration by a WHO European ministerial forum organized by the German government and held in Berlin in 2007 (e45), must now be practically implemented through support for research on the national and international levels, and through adequate financial contributions.

The situation in Germany.

The global state of tuberculosis infection and resistance has made itself felt in Germany as well. Therefore, there is still a need for effective control measures to be kept up in this country, as they have been to date.

Perspectives.

The development and testing of new diagnostic methods for tuberculosis, anti-tuberculosis drugs, and vaccines will be key components of a successful long-term effort to combat the disease.

Key Messages.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that there were 9.27 million new cases of tuberculosis and 1.78 million deaths from tuberculosis worldwide in 2007. At least 14.8% of newly diagnosed patients were co-infected with HIV.

Erroneous treatment, in particular, has promoted the selection of drug-resistant tubercle bacillus strains around the world. According to WHO estimates, there are about half a million new cases of multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis around the world each year, defined as cases in which the two most important anti-tuberculosis drugs, isoniazid and rifampicin, are ineffective.

The widespread presence of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) tuberculosis is a matter of great concern. Such infections are usually impossible either to diagnose or to treat in countries with limited resources, and they are therefore of major relevance to public health.

In Germany, the number of new tuberculosis infections is declining, and the resistance situation is (still) stable. The effects of the global situation are nonetheless making themselves felt, and effective control measures and continued vigilance against the problem remain necessary.

Not just the implementation of effective control strategies, but also the (further) development and testing of new diagnostic methods for tuberculosis and of anti-tuberculosis drugs and vaccines will be key components of a successful long-term effort to combat tuberculosis and should be actively promoted in a sustained effort.

Further Information On Cme.

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Postgraduate and Continuing Medical Education.

Deutsches Ärzteblatt provides certified continuing medical education (CME) in accordance with the requirements of the Medical Associations of the German federal states (Länder). CME points of the Medical Associations can be acquired only through the Internet, not by mail or fax, by the use of the German version of the CME questionnaire within 6 weeks of publication of the article. See the following website: cme.aerzteblatt.de

Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit “uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN). The EFN must be entered in the appropriate field in the cme.aerzteblatt.de website under

“meine Daten” (“my data”), or upon registration. The EFN appears on each participant’s CME certificate.

The solutions to the following questions will be published in issue 9/2010.

The CME unit “Lung Cancer: Current Diagnosis and Treatment” (issue 49/2009) can be accessed until 15 January 2010.

For issue 5/2010 we plan to offer the topic “Diabetic Retinopathy.”

Solutions to the CME questionnaire in issue 45/2009:

Meyburg et al.: “Principles of Pediatric Emergency Care.” Solutions: 1b, 2c, 3d, 4c, 5b, 6a, 7c, 8b, 9a, 10c

Please answer the following questions to participate in certified Continuing Medical Education. Please give only one answer to each question, choosing the one that is most fitting.

Question 1

How high was the incidence of tuberculosis in Germany in 2007?

2.1 per 100 000 population

3.1 per 100 000 population

4.1 per 100 000 population

5.1 per 100 000 population

6.1 per 100 000 population

Question 2

Which of the following is a major risk factor for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis?

Age over 60 years

Diabetes mellitus

Prior treatment for tuberculosis

Travel in third-world countries

Work in the health sector

Question 3

What is the gold standard of diagnosis of drug-resistant tuberculosis?

Laboratory testing with culture techniques

Microscopic sputum examination

Complete blood count

Interferon-gamma test

X-ray

Question 4

A patient with non-resistant tuberculosis was initially treated with four first-line medications for two months. What drug combination should be given in the four-month stabilization phase?

Pyrazinamide and isoniazid

Streptomycin and rifampicin

Isoniazid and ethambutol

Rifampicin and pyrazinamide

Isoniazid and rifampicin

Question 5

Which anti-tuberculosis drug is classified among the oral second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs in the new WHO classification?

Pyrazinamide

Kanamycin

Clofazimin

Imipenem

Terizidone

Question 6

What percentage of tuberculosis patients in Germany in 2007 who had immigrated from countries of the former Soviet Union had multidrug-resistant tuberculosis?

>4%

>6%

<8%

<10%

>12%

Question 7

What is the main reason why tuberculosis is the deadliest

bacterial infectious disease worldwide?

HIV co-infection

COPD as underlying disease

Cigarette smoking

Malnutrition

Diabetes mellitus

Question 8

Which of the following medications is often used in Germany in cases of complex resistance, even though it is not recommended for routine use by the WHO?

Linezolid

Thiocetazone

Isoniazid

Ofloxacin

Cycloserine

Question 9

What is the approximate rate, in percent, of tuberculosis-HIV co-infection in Germany?

Less than 5%

>5% to 7%

>7% to 9%

>9% to 11%

>11% to 13%

Question 10

Which of the following would be a major advance in the fight against tuberculosis?

A rapid test that could be performed directly on the sputum sample, incorporating detailed resistance testing

Serial chest x-ray examinations of the entire population

Worldwide immunization with BCG

Routine surgical treatment of resistant tuberculosis cases

The establishment of specialized tuberculosis sanatoria

BOX. Case illustration.

A 25-year-old woman from Mongolia developed a productive cough in February 2001 and had hemoptysis from May 2001 onward. A chest x-ray revealed an infiltrate in the left upper lobe, and material obtained by bronchoscopy was found microscopically to contain acid-fast bacilli. Triple anti-tuberculosis therapy with isoniazid (H), rifampicin (R) and pyrazinamide (Z) was initiated. The results of sensitivity testing only became available several weeks later and showed resistance to all first-line drugs (H, R, ethambutol [E], streptomycin [S], pyrazinamide). The patient was then hospitalized and the therapy was changed to amikacin, para-aminosalicylic acid, protionamide (PTH), levofloxacin, and terizidone. Two months of treatment with this drug combination led to sputum conversion, after which she was discharged from the hospital. The treatment was then continued for a total of two years with moxifloxacin, PTH, and terizidone, without any recurrence of tuberculosis. The presumed source of infection was the patient’s 20-year-old sister in Mongolia who had been suffering from shortness of breath, cough, and fever since October 2000. The sister was treated in Mongolia with HREZ and, later, with S as well, but her extensive bilateral tuberculosis progressed despite this treatment. Fingerprinting of the sister’s bacillar strains, performed in Germany, revealed an identical banding pattern; the resistance pattern was identical also. The sister then underwent two years of treatment with the drug combination mentioned above, and was completely cured of tuberculosis.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

We thank the German Federal Ministry of Health for its support.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest as defined by the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in the world. Report No. 4. 2008 WHO/HTM/TB/2008.394. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Emergency update. 2008 WHO/HTM/TB/2008.402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robert Koch-Institut. Bericht zur Epidemiologie der Tuberkulose in Deutschland für 2007. Robert Koch-Institut. 2009 Berlin www.rki.de. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control: epidemiology, strategy, financing. Geneva, Switzerland,: WHO; WHO/HTM/TB/2009.411. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eker B, Orzmann J, Migliori GB, et al. Multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1700–1706. doi: 10.3201/eid1411.080729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen T, Colijn C, Wright A, Zignol M, Pym A, Murray M. Challenges in estimating the total burden of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1302–1306. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200801-175PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loddenkemper R, Sagebiel D, Brendel A. Strategies against multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 2002;20(Suppl 36):66–77. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00401302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.French CE, Glynn JR, Kruijshaar ME, Ditah IC, Delpech V, Abubakar I. The association between HIV and antituberculosis drug resistance. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:718–725. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00022308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO Regional Office for Europe. Status paper on prisons and tuberculosis. Kopenhagen, Dänemark: WHO; 2007. EUR/07/5063912. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nunn P, Reid A, De Cock KM. Tuberculosis and HIV infection: the global setting. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:5–14. doi: 10.1086/518660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gandhi NR, Moll A, Sturm AW, Pawinski R, et al. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis as a cause of death in patients co-infected with tuberculosis and HIV in a rural area of South Africa. Lancet. 2006;368:1575–1580. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69573-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rüsch-Gerdes S, Hillemann D. Moderne mykobakteriologische Labordiagnostik. Pneumologie. 2008;62:533–540. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1038242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deutsches Zentralkomitee zur Bekämpfung der Tuberkulose. Richtlinien zur medikamentösen Behandlung der Tuberkulose im Erwachsenen- und Kindesalter. Pneumologie. 2001;33:494–511. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caminero JA. Treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: evidence and controversies. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:829–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaas SH, Mütterlein R, Weig J, et al. Extensively drug resistant tuberculosis in a high income country: A report of four unrelated cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8 doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon YS, Kim YH, Suh GY, et al. Treatment outcomes for HIV-uninfected patients with multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. CID. 2008;47:496–502. doi: 10.1086/590005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitnick CD, Shin SS, Seung KJ, et al. Comprehensive treatment of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:563–574. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim DH, Kim HJ, Park S-K, et al. Treatment outcomes and long-term survival in patients with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:1075–1082. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200801-132OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Building on and enhancing DOTS to meet the TB-related Millenium Development Goals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. The Stop TB Strategy. WHO/HTM/STB/2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Floyd K, Pantoja A. Financial resources required for tuberculosis control to achieve global targets set for 2015. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:568–576. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.049767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Migliori GB, Loddenkemper R, Blasi F, Raviglione MC. 125 years after Robert Koch’s discovery of the tubercle bacillus: Is “science” enough to tackle the epidemic? Eur Respir J. 2007;29:423–427. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00001307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raviglione MC, Uplekar MW. WHO’s new Stop TB Strategy. Lancet. 2006;367:952–955. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68392-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. Guidelines for establishing DOTS-Plus -projects for the management of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) Geneva, Schweiz: World Health Organization; 2000. WHO/CDS/TB/2000.278. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spigelman MK. New tuberculosis therapeutics: A growing pipeline. JID. 2007;196:S28–S34. doi: 10.1086/518663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumann S, Eddine AN, Kaufmann SHE. Progress in tuberculosis -vaccine development. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:438–448. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Migliori GB, Besozzi G, Girardi E, et al. Clinical and operational value of the extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis definition. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:623–626. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00077307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Scholten JN, de Vlas SJ, Zaleskis R. Under-reporting of HIV infection among cohorts of TB patients in the WHO European Region, 2003-2004. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Kunitz F, Brodhun B, Hauer B, Haas W, Loddenkemper R. Die aktuelle Tuberkulosesituation in Deutschland und die Auswirkungen der globalen Situation. Pneumologie. 2007;61:467–477. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-959245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Euro TB and the national coordinators for tuberculosis surveillance in the WHO European Region. Surveillance of tuberculosis in Europe. Report on tuberculosis cases notified in 2006, Institut de veille sanitaire, Saint-Maurice, France. 2008 März [Google Scholar]

- e5.Chiang C-Y, Yew WW. Multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:304–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Lange C, Grobusch MP, Wagner D. Extensiv-resistente Tuberkulose (XDR-TB) Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;133:374–376. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1046724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Amor YB, Nemser B, Singh A, Sankin A, Schluger N. Underreported threat of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1345–1352. doi: 10.3201/eid1409.061524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.World Health Organization. The global MDR-TB & XDR-TB response plan 2007-2008. Geneva: WHO; 2007. WHO/HTM/TB/2007.387. [Google Scholar]

- e9.Migliori GB, De Iaco G, Besozzi G, Centis R, Cirillo DM. First tuberculosis cases in Italy resistant to all tested drugs. Euro Surveill. 2007;12 doi: 10.2807/esw.12.20.03194-en. E070517.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Canetti G. The eradication of tuberculosis: theoretical problems and practical solutions. Tubercle. 1962;43:301–321. doi: 10.1016/s0041-3879(62)80071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Mitchison DA. Chemotherapy of tuberculosis: a bacteriologist’s viewpoint. BMJ. 1965;1:1333–1340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Vareldzis BP, Grosset J, de Kantor I, et al. Drug-resistant tuberculosis, laboratory issues. WHO recommendations. Tuberc Lung Dis. 1994;75:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(94)90096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Fox W, Ellard GA, Mitchison DA. Studies on the treatment of -tuberculosis undertaken by the British Medical Research Council Tuberculosis Units, 1946-1986, with relevant subsequent publications. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;3:231–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Frieden TR, Sterling T, Pablos-Mendez A, Kilburn JO, Cauthen GM, Dooley SW. The emergence of drug-resistant tuberculosis in New York City. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:521–526. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302253280801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Aerts A, Hauer B, Wanlin M, et al. Tuberculosis and tuberculosis control in European prisons. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;11:1213–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Faustini A, Hall AJ, Perucci CA. Risk factors for multidrug resistant tuberculosis in Europe: a systematic review. Thorax. 2006;61:158–163. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.045963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Bone A, Aerts A, Grzemska M, et al. TB control in prisons. A manual for programme managers. 2001 WHO/CDS/TB/2000.281. [Google Scholar]

- e18.Glynn JR, Kremer K, Borgdorff MW, Rodriguez MP, van Soolingen D. Beijing/W genotype Mycobacterium tuberculosis and drug resistance. European concerted action on new generation genetic markers and techniques for the epidemiology and control of tuberculosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:736–743. doi: 10.3201/eid1205.050400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Davies PDO. The world wide increase in tuberculosis: how demographic change, HIV infection and increasing numbers in poverty are increasing tuberculosis. Ann Med. 2003;35:235–243. doi: 10.1080/07853890310005713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Corbett EL, Watt CJ, Walker N, Maher D, Williams BG, Raviglione R, Dye C. The growing burden of tuberculosis. Global trends and interactions with the HIV epidemic. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1009–1021. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.9.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Schwalbe N, Harrington P. HIV and tuberculosis in the former Soviet Union. Lancet. 2002;360:19–20. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11805-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Hauer B, Kunitz F, Sagebiel D, Niemann S, Diel R, Loddenkemper R. Deutsches Zentralkomitee zur Bekämpfung der Tuberkulose. Berlin: 30. Informationsbericht; 2007. Übersicht zur DZK-Studie: „Untersuchungen zur Tuberkulose in Deutschland: Molekulare Epidemiologie, Resistenzsituation und Behandlung“; pp. 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- e23.Pai M, O’Brien R. New diagnostics for latent and active tuberculosis: state of the art and future prospects. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;29:560–568. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1085707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e24.World Health Organization and the UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO special programme for research and training in tropical di-seases (TDR) Molecular line probe assays for rapid screening of patients at risk of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). -Expert group report Mai 2008. http://www.who.int/tb/features_archive/expert_group_report_june08.pdf [Google Scholar]

- e25.Parrish N, Carrol K. Importance of improved TB diagnostics in addressing the extensively drug-resistant TB crisis. Future Microbiol. 2008;3:405–413. doi: 10.2217/17460913.3.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e26.Raviglione MC, Smith IM. XDR tuberculosis—implications for global public health. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:656–659. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e27.World Health Organization. Treatment of tuberculosis: guidelines for national programmes. 3rd ed. Genf, Schweiz: 2003. WHO/CDS/TB/2003. [Google Scholar]

- e28.Mak A, Thomas A, del Granado M, Zaleskis R, Mouzafavora N, Menzies D. Influence of multidrug resistance on tuberculosis treatment outcomes with standardized regimens. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:306–312. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-240OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e29.Franke MF, Appleton SC, Bayona J. Risk factors and mortality -associated with default from multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1844–1851. doi: 10.1086/588292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e30.Banerjee R, Allen J, Westenhouse J, et al. Extensively drug–resistant tuberculosis in California, 1993-2006. CID. 2008;47:450–457. doi: 10.1086/590009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e31.Shah NS, Pratt R, Armstrong L, Robison V, Castro KG, Cegielski JP. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in the United States, 1993-2007. JAMA. 2008;300:2153–2160. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.18.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e32.Chiang C-Y, Enarson DA, Yu MC, et al. Outcome of pulmonary multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a 6-yr follow-up study. Eur -Respir J. 2006;28:980–985. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00125705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e33.Leimane V, Riekstina V, Holtz TH, et al. Clinical outcome of individualised treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Latvia: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2005;365:318–326. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17786-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e34.Laserson KF, Thorpe LE, Leimane V, et al. Speaking the same language : treatment outcome definitions for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:640–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e35.Keshavjee S, Gelmanova I, Farmer PE, et al. Treatment of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in Tomsk, Russia: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2008;372:1403–1409. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61204-0. Epub 2008 Aug 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e36.Brown RE, Miller B, Taylor WR, et al. Health-care expenditures for tuberculosis in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1595–1600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e37.Rajbhandary SS, Marks SM, Bock NN. Costs of patients hospitalized for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:1012–1016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e38.European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) Framework action plan to fight tuberculosis in the European Union. Stockholm,: 2008. Feb, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e39.World Health Organization. Plan to stop TB in 18 high priority countries in the WHO European Region, 2007-2015. Geneva: WHO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- e40.Gupta R, Cegielski JP, Espinal MA, et al. Increasing transparency in partnerships for health—introducing the Green Light Committee. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:970–976. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e41.Caminero JA. Likelihood of generating MDR-TB and XDR-TB under adequate National Tuberculosis Control Programme implementation. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:869–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e42.Cobelens FGJ, Heldal E, Kimerling ME, et al. Scaling up programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis: a prioritised research agenda. Plos Medicine. 2008;5:1037–1042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e43.Global Stop TB Partnership. www.stoptb.org. [Google Scholar]

- e44.Globaler Fond zur Bekämpfung von AIDS, Tuberkulose und Malaria. www.theglobalfund.org [Google Scholar]

- e45.Europäisches Ministerforum der Weltgesundheitsorganisation (WHO) “All against tuberculosis” am 22. Oktober 2007 in Berlin. http://www.euro.who.int/tuberculosis/TBForum/20070621_1?language=German [Google Scholar]