Abstract

Long-term potentiation (LTP) of synaptic transmission provides an experimental model for studying mechanisms of memory1. The classical form of LTP relies on N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs), and it has emerged that astroglia can regulate their activation through Ca2+-dependent release of the NMDAR co-agonist D-serine2-4. Release of D-serine from glia enables LTP in cultures5 and explains a correlation between glial coverage of synapses and LTP in the supraoptic nucleus4. However, Ca2+ elevations in astroglia can also release other signalling molecules, most prominently glutamate6-8, Adenosine-5′-triphosphate9, and Tumor-Necrosis-Factor-α10,11 whereas neurons themselves can synthesise and supply D-serine12,13. Furthermore, loading an astrocyte with exogenous Ca2+ buffers does not suppress LTP in hippocampal area CA114-16, and the physiological relevance of experiments in cultures or strong exogenous stimuli applied to astrocytes has been questioned17,18. The involvement of glia in LTP induction thus remains controversial. Here we show that clamping internal Ca2+ in individual CA1 astrocytes blocks LTP induction at nearby excitatory synapses by reducing the occupancy of the NMDAR co-agonist sites. This LTP blockade can be reversed by exogenous D-serine or glycine whereas depletion of D-serine or disruption of exocytosis in an individual astrocyte blocks local LTP. We thus demonstrate that Ca2+-dependent release of D-serine from an astrocyte controls NMDAR-dependent plasticity in many thousands of excitatory synapses occurring nearby.

To investigate the role of astrocytes in NMDAR-dependent LTP, we focused on Schaffer collateral (SC) - CA1 pyramidal cell synapses, a classical subject of LTP studies. We patched passive stratum radiatum astrocytes (Supplementary Fig. 1) and monitored SC-mediated field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) in their immediate vicinity (Fig. 1a-b, Supplementary Fig. 1). A standard high-frequency stimulation (HFS) protocol induced LTP which was indistinguishable from that induced without patching an astrocyte (Fig. 1c; Methods). Because the intracellular solution routinely contained the high-affinity Ca2+ indicator Oregon Green BAPTA-1 (OGB-1, 0.2 mM), these observations were in correspondence with studies documenting robust LTP near an astrocyte loaded with 10 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA)14-16. However, exogenous Ca2+ buffers, while suppressing rapid Ca2+ transients, are unlikely to affect equilibrated (resting) free Ca2+ controlled by active homeostatic mechanisms. To constrain free astrocytic Ca2+ more efficiently, we “clamped” its concentration at 50-80 nM, by adding 0.45 mM EGTA and 0.14 mM Ca2+ to the intracellular solution (Methods)19. Indeed, Ca2+ clamp abolished HFS-induced Ca2+ elevations which could be detected in astrocytes containing OGB-1 and EGTA only (Supplementary Fig. 2). Furthermore, biophysical simulations suggested that Ca2+ clamp could restrict Ca2+ nanodomains more efficiently than buffers alone (Supplementary Fig. 3).

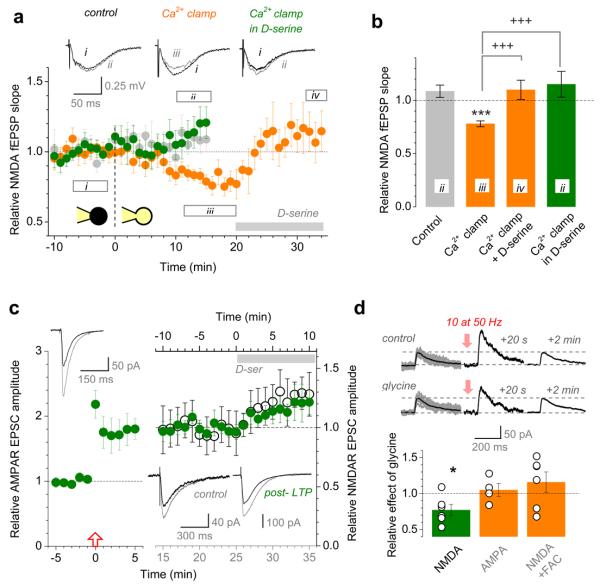

Figure 1. Clamping astrocytic Ca2+ blocks LTP at nearby synapses in a D-serine-dependent manner.

a, Experimental arrangement: ip, intracellular patch-pipette; ep, extracellular pipette; green line, Schaffer collaterals.

b, A typical patched astrocyte (Alexa Fluor 594, ~120 μm stack fusion); ep and ip as in a; bv, blood vessel; escape of Alexa to neighbouring cells can be seen; inset: DIC at lower magnification.

c, LTP of AMPAR fEPSPs in control conditions, with (n = 23, green) or without (n = 29, grey) astrocyte patched. Arrow, HFS onset; traces, characteristic AMPAR fEPSPs before (black) and after (grey) LTP induction; notations apply in c-e.

d, Clamping astrocytic Ca2+ (0.2 mM OGB-1, 0.45 mM EGTA, 0.14 mM CaCl2) abolishes local LTP (n = 19, orange) whereas 10 μM D-serine rescues it (n = 10, green).

e, LTP in 10 μM D-serine (163 ± 12%, n = 8, green; no astrocyte patched) is no different from that in control (Fig. 1c) suggesting saturation of either the NMDAR co-agonist site or the downstream induction mechanism. 50 μM APV completely blocks LTP (n = 12, orange).

f, Summary for experiments in c-e, as indicated. Bars, mean ± s.e.m for fEPSPs measured 25-30 min post-HFS relative to baseline. ***, p < 0.005 (one-population t-test); +++, p < 0.002 (two-population t-test).

Strikingly, clamping intra-astrocyte Ca2+ completely suppressed LTP at nearby synapses, and adding 10 μM D-serine fully rescued it (Fig. 1d). D-serine alone had no effect on LTP in control conditions (consistent with previous reports20) whereas the NMDAR antagonist (2R)-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV) completely blocked it (Fig. 1e-f). These observations imply that Ca2+-dependent astrocyte activity could indeed control supply of an NMDAR co-agonist essential for LTP induction4,5,18,21. To understand the underlying mechanisms, we recorded SC-evoked NMDAR fEPSPs near the patched astrocyte (Fig. 1a-b; Methods) while switching from cell-attached to whole-cell configuration (Fig. 2a). The control pipette solution (Methods) had little influence on NMDAR responses (change 9 ± 6% relative to baseline, n = 6; Fig. 2a-b) whereas Ca2+ clamp reduced them by 22 ± 4% (n = 13, p < 0.0001). This reduction was reversed by the subsequent application of D-serine (10 ± 9% relative to baseline, n = 7, p = 0.0012; Fig. 2a-b; Supplementary Fig. 4), and having D-serine from the start blocked the inhibitory effect of Ca2+ clamp (15 ± 12%, n = 7; Fig. 2a-b). Ca2+-dependent astrocyte signalling could therefore regulate the occupancy of the NMDAR co-agonist site.

Figure 2. Activation of the NMDAR co-agonist site is astrocyte- and use-dependent.

a, NMDAR fEPSP slope (Fig. 1a arrangement) monitored during the transition from cell-attached to whole-cell mode, as indicated. Grey circles, control (n = 6; Methods); orange, Ca2+ clamp (n = 7 throughout, n = 13 before D-serine application); green, Ca2+ clamp with 10 μM D-serine in bath (n = 7). Segments, averaging epochs; traces, examples (also Supplementary Fig. 4).

b, Summary of experiments shown in a. Bars, mean ± s.e.m. (applies throughout); numerals, epochs in a. ***, p < 0.0001 (one-population t-test); +++, p < 0.005 (two-population t-tests).

c, The effect of D-serine on NMDAR EPSCs before and after LTP induction. Green circles, the amplitude of AMPAR EPSCs (n = 6; left panel; Vm = −70 mV) and, subsequently, NMDAR EPSCs in the same cell post-LTP (right panel; 10 μM NBQX, Vm = −10 mV); grey segment, D-serine application. Open circles (n = 5; top axis, right panel), NMDAR EPSC amplitudes in no-LTP conditions. Traces: upper-left, characteristic AMPAR EPSCs in control (black) and post-LTP (grey); lower-right, NMDAR EPSCs before (black) and after (grey) application of D-serine, in control and post-LTP, as indicated.

d, 10 pulses at 50 Hz transiently potentiates synaptic NMDAR responses in a glycine- and glia- dependent manner. Traces: examples of single-stimulus EPSCs including a prominent NMDAR-mediated component (Vm = +40 mV; no AMPAR blockade was used to ensure pharmacological continuity with LTP induction protocols) in baseline conditions (left; grey, individual traces; black, average), 20 seconds (middle), and 2 min after the stimulus train (right), in control (upper row) and in 0.1 mM glycine (lower row). Bar graph: average ratio (post-train EPSC potentiation in glycine) / (post-train EPSC potentiation in control) for test experiments illustrated by traces (green; average change of the NMDAR-mediated response expressed as the area under the EPSC curve over the 100-300 ms post-peak interval: −23 ± 8%, p = 0.032, n = 6), and also for control experiments (orange) including AMPAR EPSCs (amplitude change 5 ± 9%; p = 0.41, n = 4) and NMDAR EPSCs in FAC (15 ± 14%; p = 0.32, n = 6), as indicated (examples in Supplementary Fig. 6); circles, individual experiments.

In resting conditions, 10 μM D-serine increased NMDAR-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in CA1 pyramidal cells (by 29 ± 10%; n = 5, p = 0.039; Fig. 2c) as well as local NMDAR fEPSPs (by 25.3 ± 3.0%, n = 8, p < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. 5) indicating that the NMDAR co-agonist sites were not saturated in baseline conditions, consistent with recent observations in hippocampal slices22 and in vivo23. Interestingly, LTP induction had no long-term effect on the NMDAR co-agonist site occupancy: D-serine applied 25 min post-induction equally increased NMDAR EPSCs (by 23 ± 8%, n = 6, p = 0.034, Fig. 2c) and fEPSPs (by 24.7 ± 9.1%; n = 6, p = 0.042, Supplementary Fig. 5), which was indistinguishable from the pre-induction effects. In contrast, even mild repetitive stimulation of SCs (10 stimuli at 50 Hz) was sufficient to boost the co-agonist site occupancy transiently: short-term potentiation of the NMDAR-mediated EPSC component 20 s post-train was reduced by 20 ± 7% (n = 6, p = 0.043) when the co-agonist site was saturated by 0.1 mM glycine, before returning to the baseline level two minutes later (Fig. 2d). This was not due to changes in cell excitability or release probability because similar potentiation of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPAR) responses showed no glycine sensitivity (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Fig. 6). Furthermore, the glial metabolic poison fluoroacetate (FAC, 5 mM) made the NMDAR EPSC potentiation also insensitive to glycine, thus implicating glia (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Fig. 6). In striking correspondence with these observations, HFS induced transient Ca2+ elevations in 54% of astrocytes (consistent with earlier reports24) but no long-term changes in spontaneous Ca2+ activity (Supplementary Fig. 7).

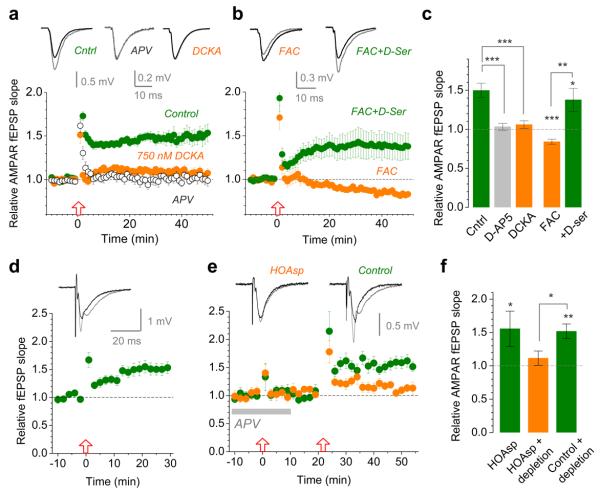

If astrocytes enable LTP induction by increasing activation of the NMDAR co-agonist site then reducing the site availability should prevent LTP25. To replicate the ~25% decrease of NMDAR responses under astrocytic Ca2+ clamp (Fig. 2a-b), we used the selective NMDAR glycine site blocker 5,7-dichlorokynurenic acid (DCKA) at 750 nM (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 8). Strikingly, 750 nM DCKA abolished LTP just as did 50 μM APV (Fig. 3a). Consistent both with these observations and with the Ca2+ clamp effects, FAC also reduced NMDAR fEPSPs by 23 ± 4% (n = 16, p = 0.00017; Supplementary Fig. 9a-b) and blocked LTP in a D-serine-sensitive manner (Fig. 3b-c). Although the mechanisms and specificity of FAC actions are incompletely understood, we confirmed that the effect of FAC on NMDAR fEPSPs (i) paralleled that on LTP (Supplementary Fig. 9c-d), (ii) was absent in glycine, and (iii) did not involve changes in release probability or axonal excitability (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Figure 3. LTP expression depends on the occupancy of the NMDAR co-agonist sites controlled by D-serine synthesis in a nearby astrocyte.

a, LTP of AMPAR fEPSPs in control conditions (n = 10; green circles) is abolished by either 50 μM APV (open circles, n = 12) or 750 nM DCKA (n = 9; orange; dose-response curve in Supplementary Fig. 8). Traces, characteristic responses in control (black) and following LTP induction (grey).

b, Incubation with 5 mM FAC for >50 min blocks LTP (n = 16, orange circles) whereas 10 μM D-serine rescues it (n = 16; green circles). Notation is as in a.

c, Summary of experiments depicted in a-b. Bars, mean ± s.e.m. (applies throughout); *, p = 0.0127; **, p = 0.0014; ***, p < 0.001 (two-population t-test).

d, 400 μM intra-astrocyte HOAsp does not suppress LTP induction (potentiation is 50 ± 15%, n = 6, p = 0.021; arrangement as in Fig. 1a); traces, average fEPSPs before (black) and after (grey) application of HFS, one-cell example; time scale applies to d-e.

e, Intra-astrocyte HOAsp blocks induction of LTP (fEPSP change: +12 ± 11%, n = 7, p = 0.32; orange) following depletion of D-serine using HFS in APV; arrows, HFS onset. Omitting HOAsp robustly induces LTP (52 ± 11%, n = 6, p = 0.0052; green). HOAsp was unlikely to affect glutamate metabolism because no rundown of glutamatergic responses was observed.

f, Summary of experiments shown in d-e. * (left), p = 0.021; **, p = 0.0052 (one-population t-test); * (right), p = 0.024 (two-population t-test).

Such experiments however provide no direct evidence for D-serine release from astroglia: an alternative scenario is that an NMDAR co-agonist is released from elsewhere, e.g. neurons12,13, in response to an unknown astrocytic signal. To investigate this, we blocked D-serine synthesis inside an astrocyte using the relatively specific serine racemase inhibitor L-erythro-3-hydroxyaspartate (HOAsp)26 loaded at 400 μM (to suppress competition from L-serine), but found no effect on local LTP (Fig. 3d). However, HOAsp does not influence D-serine itself and therefore cannot prevent release of the stored agonist. We therefore attempted to deplete the putative astrocytic D-serine pool by applying HFS in the presence of APV. When APV was washed out and HFS applied again, LTP induction was indeed suppressed whereas the same protocol with no HOAsp loaded yielded robust potentiation (Fig. 3e-f). This result demonstrates causality between astrocytic synthesis of D-serine and local LTP.

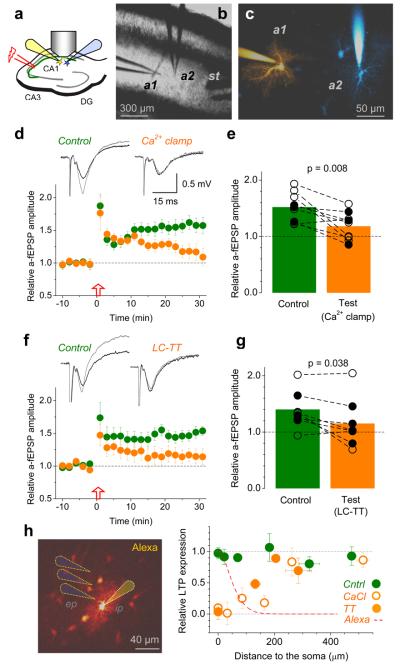

How far do individual CA1 astrocytes extent their influence on LTP? Although astrocytes occupy separate domains27, they can communicate through gap junctions28 which are left intact in the present study. To determine whether these cells could act independently, we monitored LTP simultaneously in two neighbouring areas associated with two astrocytes. Firstly, we confirmed that field potentials recorded through an astrocytic patch-pipette reliably represent local fEPSPs, with no bias from glutamate transporter or potassium currents14 (Supplementary Fig. 11). We next patched two neighbouring astrocytes and monitored SC-evoked “astrocytic” fEPSPs (a-fEPSPs) representing the two respective areas (Fig. 4a-c). Clamping Ca2+ in one astrocyte suppressed LTP at nearby synapses but not at synapses near the neighbouring, control cell (Fig. 4d-e, Supplementary Fig. 12). A qualitatively identical result was obtained when putative vesicular exocytosis of D-serine21,29 in the test astrocyte was suppressed by the light-chain tetanus toxin (LC-TT; Fig. 4f-g, Supplementary Fig. 12). In complementary experiments, we varied the distance between the extracellular recording pipette and the patched astrocyte. In Ca2+ clamp conditions, LTP partly recovered at 70-100 μm from the patched soma reaching its full strength at >200 μm, consistent with the profile of Alexa escaping to neighbouring cells (Fig. 4h, Supplementary Fig. 13). With a LC-TT-loaded astrocyte, LTP recovery occurred at markedly shorter distances (Fig. 4h), consistent with the toxin's inability to cross gap junctions.

Figure 4. Individual astrocytes influence LTP induction mainly at nearby synapses.

a, Experimental arrangement; notations as in Fig. 1a.

b-c, An experiment seen in DIC (b) and in Alexa channel (c); a1 and a2, two patched astrocytes (λx2P = 800 nm, ~150 μm z-stack; false colours: sequential staining of a1 and a2 followed by subtraction of a1 image from combined a1+a2 image, Methods); st, stimulating electrode.

d, Ca2+ clamp in test astrocyte suppresses local LTP, but not LTP near the neighbouring control astrocyte. Graph, a-fEPSP amplitudes (mean ± s.e.m.) recorded from the control (green) and test (orange) astrocyte (n = 9). Traces, respective characteristic a-fEPSPs (Supplementary Fig. 11) recorded before (black) and after (grey) LTP induction. Incomplete blockade of early potentiation near the test cell was likely due to delayed equilibration between the two dialysing pipettes.

e, Summary of experiments in d; connected circles, recorded astrocyte pairs; black and hollow circles, experiments in which the test cell was, respectively, closer to and further away from the stimulating electrode (which might bias LTP expression); p-values, paired t-test (n = 9).

f-g, Experiments similar to those shown in d-e, but with the test astrocyte loaded with the LC-TT (n = 8). Other notation is as in d-e. Slow equilibration of high molecular weight LC-TT might explain incomplete block of early potentiation near the test cell.

h, Left panel, experimental arrangement (as in Fig. 1a-b): dotted cones, depiction of the extracellular pipette (ep). Graph: circles, relative potentiation (± s.e.m.) of AMPAR fEPSPs at different distances from the patched soma in control (n = 34; green), Ca2+-clamp (n = 48; open orange) and LC-TT (n = 15, filled orange) experiments. Dashed red line, the average emission intensity profile of Alexa (whole-cell loaded at 40 μM) escaping to neighbouring cells (n = 215 astrocytes imaged in eight 3-D stacks; details in Supplementary Fig. 13).

Our findings demonstrate that induction of NMDAR-dependent LTP at excitatory hippocampal synapses depends on the availability of NMDARs provided by Ca2+-dependent release of D-serine from a local astrocyte. Repetitive synaptic activity transiently enhances D-serine supply by glia, paralleled by a short-term elevation in astrocytic Ca2+. Neighbouring astrocytes may have distinct effects on local synapses, but also extend their influence beyond their morphological boundaries. This could potentially give rise to a Hebbian mechanism regulating hetero-synaptic NMDAR-dependent plasticity across a neuropil domain affected by an activated astrocyte. The importance of D-serine for LTP does not exclude the potential role of astrocytic glutamate release6,8, and the precise mechanisms acting on the microscopic scale require further investigation. Individual astrocytes occupy ~9·104 μm3 of CA1 neuropil (while overlapping by only 3-10%)27, and the numeric synaptic density in this area is ~2 μm−3 (ref.30) thus suggesting that a single astrocyte could affect synaptic plasticity on hundreds of principal cells.

METHODS SUMMARY

Whole-cell recordings from passive astrocytes (n = 146) were made in stratum radiatum, area CA1 in acute transverse hippocampal slices prepared from adult rats. Cells (30-100 μm deep inside the slice) were loaded with a bright morphological tracer Alexa Fluor 594 and the high-affinity Ca2+ indicator Oregon Green BAPTA (OGB-1) and imaged in two-photon excitation mode (λ2px = 800 nm). Field EPSPs were recorded using either an extracellular recording electrode placed in the immediate vicinity of the visualised astrocyte dendritic arbour or through the astrocytic patch pipette, as described. Whole-cell EPSCs were recorded from CA1 pyramidal cells. Electric stimuli were applied to Schaffer collateral fibres. LTP was induced by a standard high-frequency stimulation protocol (three 100-pulse trains at 100 Hz, 60 or 20 seconds apart). Inside the recorded astrocyte, conditions of Ca2+ homeostasis were altered using intracellular solutions containing EGTA, Oregon Green BAPTA-1, and CaCl2; the exocytosis machinery was suppressed using light-chain tetanus toxin; synthesis of D-serine was inhibited with serine racemase inhibitor L-erythro-3-hydroxyaspartate (HOAsp).

METHODS

Preparation

350 μm thick acute hippocampal slices were obtained from four to eight week-old male Sprague-Dawley or Wistar rats, in full compliance with national guidelines on animal experimentation. Slices were prepared in an ice-cold slicing solution containing (in mM): NaCl 75, sucrose 80, KCl 2.5, MgCl2 7, NaH2PO4 1.25, CaCl20.5, and glucose 6 (osmolarity 300-310 mOsm), stored in the slicing solution at 34°C for 15 minutes before being transferred to an interface chamber for storage in an extracellular solution containing (in mM) NaCl 119, KCl 2.5, MgSO4 1.3, NaH2PO4 1, NaHCO3 26, CaCl2 2, and glucose 10 (osmolarity adjusted to 295-305 using glucose). All solutions were continuously bubbled with 95% O2/ 5% CO2. Slices were allowed to rest for at least 60 minutes before recordings started. For recordings, slices were transferred to the submersion-type recording chamber and superperfused, at 23-26 °C, with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) saturated with 95%O2/5%CO2 containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3 and 12 glucose (pH 7.4; osmolarity 295-305) in the presence of 1.3 mM Mg2+ and either 2.0 or 2.5 mM Ca2+ (where necessary, 50 μM picrotoxin was added to block GABAA receptors and a cut between CA3 and CA1 was made to suppress epileptiform activity).

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell recordings in astrocytes were obtained using standard patch pipettes (3-4 MΩ) filled with a “control” intracellular solution containing (in mM) KCH3O3S 135, HEPES 10, Na2-Phosphocreatine 10, MgCl2 4, Na2-ATP 4, Na-GTP 0.4 (pH adjusted to 7.2 using KOH, osmolarity 290-295). Cell-impermeable dyes Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 (200 μM, Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 594 hydrazide (40 μM, Invitrogen) were routinely added to the intracellular solution, unless indicated otherwise. Passive (protoplasmic) astrocytes were identified, in accordance with established criteria14,31,32, by their small soma size (~ 10 μm; visualised in the Alexa emission channel), low resting potential (mean ± s.e.m.: −86.8 ± 1.2 mV, n = 146, no correction for the liquid-junction potential) and low input resistance (8.4 ± 0.6 MΩ, n = 146); we confirmed that they had passive (ohmic) properties and characteristic morphology of the arbour (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Cells that showed atypical morphologies (3 out of 186) were discarded. Astrocytes were either held in voltage clamp mode at their resting membrane potential or in current clamp. In some experiments, the recombinant tetanus toxin light chain (1 μM, LC-TT, Quadratech Diagnostics Ltd., UK) was included in the intracellular solution to disrupt vesicular release33. Where specified, 0.45 mM EGTA and 0.14 mM CaCl2 were added to the control intracellular solution to clamp intracellular free Ca2+ at a steady-state level of 50-80 nM (calculation by WebMaxChelator, Stanford). When required, the most effective to date specific serine racemase inhibitor L-erythro-3-hydroxyaspartate (HOAsp, Wako Chemicals; KI = 49 μM)26 was added to the intracellular solution.

Where indicated, the extracellular recording pipette was placed within the arbour or in the immediate vicinity of the patched astrocyte visualised in the Alexa channel, <90 μm from the soma (Fig. 1). Synaptic responses were evoked by orthodromic stimulation (100 μs, 40-120 μA) of Schaffer collaterals using either a bipolar or coaxial stimulation electrode placed in the stratum radiatum >200 μm away from the recording electrodes. Field EPSPs (fEPSPs) were recorded using a standard patch pipette filled with the extracellular solution. Predominantly AMPAR-mediated fEPSPs (with no NMDAR blockers added) are denoted AMPAR fEPSPs throughout the text; where required, NMDAR fEPSPs were isolated using 10 μM NBQX and 0.2 mM Mg2+ in the bath medium (except for post-LTP recordings performed in 1.3 mM Mg2+, to maintain unchanged cell excitability).

The paired-pulse interval was 100 to 200 ms and the paired-pulse ratio was defined as the slope2/slope1 ratio. In some experiments, excitatory synaptic responses were monitored as field potentials recorded through one or two astrocyte patch-pipette in current clamp mode (a-fEPSP; Supplementary Fig. 11). The stimulus intensity was normally set at ~70% of that triggering population spikes, stimuli were applied every 30 seconds for at least 15 minutes before the LTP was induced using three trains of high-frequency stimulation (HFS, 100 pulses at 100 Hz), either 60 or 20 seconds apart. The slope of fEPSPs was monitored for subsequent 30-50 minutes.

Whole-cell recordings in CA1 pyramidal neurons were carried out using an intracellular solution containing (in mM) K-gluconate 130, KCl 5, HEPES, 10, Na2-Phosphocreatine 10, MgCl2 2, Na2-ATP 4, Na-GTP 0.4, or, alternatively, Cs+ methane sulfonate 150, MgCl21.3, EGTA 1, HEPES 10, CaCl 0.1. AMPAR EPSCs in CA1 pyramidal cells were recorded at Vm = -70 mV, and NMDAR EPSCs were recorded in at Vm = −10 mV in the presence of 10 μM NBQX, unless indicated otherwise.

Where required, slices were pre-incubated in the glial metabolism inhibitor sodium fluoroacetate (FAC)34 for at least 50 minutes, unless indicated otherwise; D-serine was added 10 to 15 minutes prior to LTP induction. Recordings were carried out using a Multiclamp 700A or 700B (Molecular Devices). Signals were filtered at 3-6 kHz, digitized and sampled through an AD converter (National Instruments) at 10 kHz, and stored for off-line analysis using either LabView (National Instruments) routines or pClamp9 software (Molecular Devices). Receptor blockers were purchased from Tocris, FAC from Sigma-Aldrich.

Two-photon excitation imaging

We used a Radiance 2100 imaging system (Zeiss-Biorad) optically linked to a femtosecond pulse laser MaiTai (SpectraPhysics-Newport) and integrated with patch-clamp electrophysiology35. Once in whole-cell mode, Alexa normally equilibrated across the astrocyte tree within 10-15 min. Astrocytes loaded with fluorescence indicators (see above) were imaged as 3-D stacks of 60-100 optical sections in the Alexa emission channel (540LP/700SP filter; λx2P = 800 nm), collected in image frame mode (512 × 512 pixels, 8-bit) at 0.5-1 μm steps.

For illustration purposes, the stacks were z-axis averaged using ImageJ routines (Rasband WS, ImageJ, NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/, 1997-2008). Transient Ca2+ signals evoked in patched astrocytes by HFS (Supplementary Fig. 2) were imaged in the OGB-1 (green) channel (515/30 filter) in line scan mode (500 Hz), and corrected for focus fluctuations in the Alexa (red) channel, as detailed elsewhere35-37 and illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 2.

To image Ca2+ activity simultaneously in a population of astrocytes (Supplementary Fig. 7), slices were incubated with the glia-specific dye sulforhodamine 101 (5 μM, SR101, Invitrogen) and the Ca2+-indicator Fluo-4 AM or OGB-1 AM (5 μM, Invitrogen), in the presence of 0.04% Pluronic (Invitrogen), for 40-50 minutes at 37 °C and allowed to rest for at least 20 minutes. The viability of loaded slices was verified by monitoring fEPSPs in response to Schaffer collateral stimulation, as described above. Time lapse imaging was carried out by acquiring 800-20000 pairs of SR101 and Fluo4 / OGB-1 fluorescence image frames at a rate of 2 Hz (256 × 256 pixels) or 7 Hz (64 × 64 pixels). In order to evoke a Ca2+ response, HFS (100 pulses at 100 Hz) was delivered halfway through the experiment. In these experiments, time-dependent fluorescent transients were expressed as F/F0 where F denotes the averaged, background-corrected Fluo-4 / OGB-1 fluorescence of a SR101 positive (astrocytic) soma.

Visualisation of astrocytic pairs and separating images of individual astrocytes in dual-patch experiments (Fig. 5) was carried out using the following routine: (a) cell 1 was patched, the dye was allowed to equilibrate and the resulting “cell-1 image” (3-D stack) was stored; (b) cell 2 was patched, the dye was equilibrated and the resulting “cell-1 + cell-2 image” was stored; (c) “cell-1 image” was subtracted from “cell-1 + cell-2 image” thus yielding the fluorescent “cell-2 image”. Comparing “cell-1 image” and “cell-2 image” could be used to reveal staining (diffusion) overlap between the two cells, which could be visualised using false colour tables applied to the two images. Image analyses were carried out offline using ImageJ.

Statistics

Group data are routinely reported as mean ± s.e.m., unless indicated otherwise, and the statistical difference between the population averages was estimated using the t-test (for paired or independent samples). Two-tailed tests were routinely used, and sample pairing was used where appropriate, e.g., when monitoring real-time changes in a parameter against its baseline value or when comparing cells in paired recordings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Human Frontier Science Programme (DAR and SHRO), Wellcome Trust (Senior Fellowship to DAR), Medical Research Council (UK), European Union (Promemoria), Inserm, Université de Bordeaux, Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (Equipe FRM to SHRO), NARSAD (Independent Investigator to SHRO), Agence National de la Recherche, Fédération pour la Recherche sur le Cerveau, Conseil Régional d'Aquitaine and a studentship from the French Ministry of Research to TP. The authors thank Dimitri Kullmann, Jeffrey Diamond, Tim Bliss, Jean-Pierre Mothet and Kirill Volynski for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is online.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bliss TVP, Collingridge GL. A Synaptic Model of Memory - Long-Term Potentiation in the Hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schell MJ, Molliver ME, Snyder SH. D-serine, an endogenous synaptic modulator: localization to astrocytes and glutamate-stimulated release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3948–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mothet JP, et al. D-serine is an endogenous ligand for the glycine site of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4926–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panatier A, et al. Glia-derived D-serine controls NMDA receptor activity and synaptic memory. Cell. 2006;125:775–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Y, et al. Contribution of astrocytes to hippocampal long-term potentiation through release of D-serine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15194–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2431073100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bezzi P, et al. Prostaglandins stimulate calcium-dependent glutamate release in astrocytes. Nature. 1998;391:281–5. doi: 10.1038/34651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fellin T, et al. Neuronal synchrony mediated by astrocytic glutamate through activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. Neuron. 2004;43:729–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perea G, Araque A. Astrocytes potentiate transmitter release at single hippocampal synapses. Science. 2007;317:1083–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1144640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pascual O, et al. Astrocytic purinergic signaling coordinates synaptic networks. Science. 2005;310:113–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1116916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bezzi P, et al. CXCR4-activated astrocyte glutamate release via TNFalpha: amplification by microglia triggers neurotoxicity. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:702–10. doi: 10.1038/89490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stellwagen D, Malenka RC. Synaptic scaling mediated by glial TNF-alpha. Nature. 2006;440:1054–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kartvelishvily E, Shleper M, Balan L, Dumin E, Wolosker H. Neuron-derived D-serine release provides a novel means to activate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:14151–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512927200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miya K, et al. Serine racemase is predominantly localized in neurons in mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2008;510:641–54. doi: 10.1002/cne.21822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diamond JS, Bergles DE, Jahr CE. Glutamate release monitored with astrocyte transporter currents during LTP. Neuron. 1998;21:425–33. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luscher C, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Monitoring glutamate release during LTP with glial transporter currents. Neuron. 1998;21:435–41. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80552-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ge WP, Duan SM. Persistent enhancement of neuron-glia signaling mediated by increased extracellular K+ accompanying long-term synaptic potentiation. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:2564–2569. doi: 10.1152/jn.00146.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiacco TA, et al. Selective stimulation of astrocyte calcium in situ does not affect neuronal excitatory synaptic activity. Neuron. 2007;54:611–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agulhon C, et al. What is the role of astrocyte calcium in neurophysiology? Neuron. 2008;59:932–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker PF, Knight DE, Umbach JA. Calcium Clamp of the Intracellular Environment. Cell Calcium. 1985;6:5–14. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(85)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duffy S, Labrie V, Roder JC. D-serine augments NMDA-NR2B receptor-dependent hippocampal long-term depression and spatial reversal learning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1004–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mothet JP, et al. Glutamate receptor activation triggers a calcium-dependent and SNARE protein-dependent release of the gliotransmitter D-serine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5606–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408483102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Krupa B, Kang JS, Bolshakov VY, Liu GS. Glycine Site of NMDA Receptor Serves as a Spatiotemporal Detector of Synaptic Activity Patterns. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:578–589. doi: 10.1152/jn.91342.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fellin T, et al. Endogenous nonneuronal modulators of synaptic transmission control cortical slow oscillations in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906419106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porter JT, McCarthy KD. Hippocampal astrocytes in situ respond to glutamate released from synaptic terminals. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5073–5081. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05073.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cummings JA, Mulkey RM, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Ca2+ signaling requirements for long-term depression in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1996;16:825–33. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strisovsky K, Jiraskova J, Mikulova A, Rulisek L, Konvalinka J. Dual substrate and reaction specificity in mouse serine racemase: Identification of high-affinity dicarboxylate substrate and inhibitors and analysis of the beta-eliminase activity. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13091–13100. doi: 10.1021/bi051201o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bushong EA, Martone ME, Jones YZ, Ellisman MH. Protoplasmic astrocytes in CA1 stratum radiatum occupy separate anatomical domains. J Neurosci. 2002;22:183–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00183.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rouach N, Koulakoff A, Abudara V, Willecke K, Giaume C. Astroglial metabolic networks sustain hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science. 2008;322:1551–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1164022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martineau M, Galli T, Baux G, Mothet JP. Confocal imaging and tracking of the exocytotic routes for D-serine-mediated gliotransmission. Glia. 2008;56:1271–84. doi: 10.1002/glia.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rusakov DA, Kullmann DM. Extrasynaptic glutamate diffusion in the hippocampus: ultrastructural constraints, uptake, and receptor activation. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3158–70. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03158.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

REFERENCES (METHODS)

- 31.Bergles DE, Jahr CE. Glial contribution to glutamate uptake at Schaffer collateral-commissural synapses in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7709–7716. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07709.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Volterra A, Meldolesi J. Astrocytes, from brain glue to communication elements: the revolution continues. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:626–40. doi: 10.1038/nrn1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu T, Binz T, Niemann H, Neher E. Multiple kinetic components of exocytosis distinguished by neurotoxin sensitivity. Nature Neurosci. 1998;1:192–200. doi: 10.1038/642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szerb JC, Issekutz B. Increase in the stimulation-induced overflow of glutamate by fluoroacetate, a selective inhibitor of the glial tricarboxylic cycle. Brain Res. 1987;410:116–20. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(87)80030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rusakov DA, Fine A. Extracellular Ca2+ depletion contributes to fast activity-dependent modulation of synaptic transmission in the brain. Neuron. 2003;37:287–297. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00025-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oertner TG, Sabatini BL, Nimchinsky EA, Svoboda K. Facilitation at single synapses probed with optical quantal analysis. Nature Neurosci. 2002;5:657–664. doi: 10.1038/nn867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scott R, Ruiz A, Henneberger C, Kullmann DM, Rusakov DA. Analog modulation of mossy fiber transmission is uncoupled from changes in presynaptic Ca2+ J Neurosci. 2008;28:7765–73. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1296-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.