Abstract

In the protozoan parasite Leishmania, abundant surface and secreted molecules such as lipophosphoglycan (LPG)1 and proteophosphoglycans (PPGs) contain extensive galactose residues in the form of phosphoglycans (PGs) containing [Gal-Man-PO4] repeating units. PGs are synthesized in the parasite Golgi apparatus and require transport of cytoplasmic nucleotide-sugar precursors to the Golgi lumen by nucleotide sugar transporters (NSTs). GDP-Man transport is mediated by the LPG2 gene product, and here we focused on transporters for UDP-Gal. Database mining revealed twelve candidate NST genes in the L. major genome, including LPG2, as well as a candidate endoplasmic reticulum UDP-glucose transporter (HUT1L), and several pseudogenes. Gene knockout studies established that two genes (LPG5A and LPG5B) encoded UDP-Gal NSTs. While the single lpg5A− and lpg5B− mutants produced PGs, an lpg5A−/5B− double mutant was completely deficient. PG synthesis was restored in the lpg5A−/5B− mutant by heterologous expression of the human UDP-Gal transporter, and heterologous expression of LPG5A and LPG5B rescued the glycosylation defects of the mammalian Lec8 mutant, which is deficient in UDP-Gal uptake. Interestingly, the LPG5A and LPG5B functions overlap but are not equivalent, as the lpg5A− mutant showed a partial defect in LPG but not PPG phosphoglycosylation, while the lpg5B− mutant showed a partial defect in PPG but not LPG phosphoglycosylation. Identification of these key NSTs in Leishmania will facilitate the dissection of glycoconjugate synthesis and its role(s) in the parasite life cycle and further our understanding of NSTs generally.

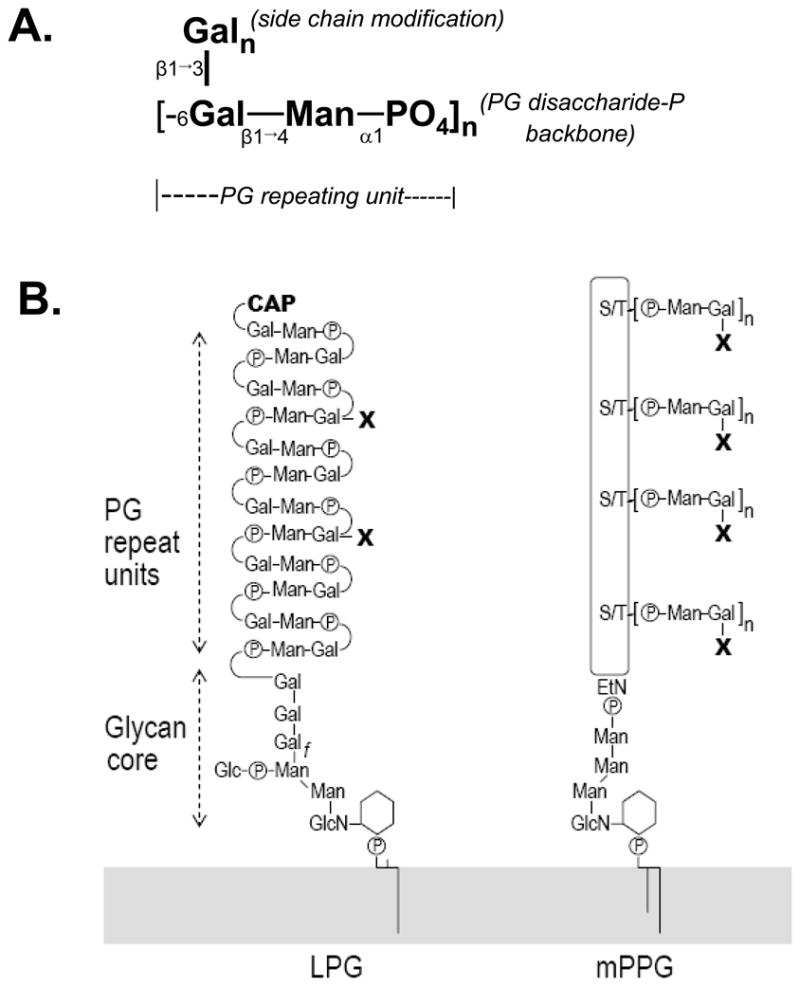

Protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania must survive in two separate and harsh environments to complete their life cycle: extracellularly within the midgut of the sand fly and intracellularly within the phagolysosome of vertebrate macrophages. A variety of abundant secreted and surface glycoconjugates have been implicated in key steps of the infectious cycle (1). Several of the most abundant of these contain repeating phosphoglycan (PG) polymers, such as lipophosphoglycan (LPG) and proteophosphoglycans (PPGs) (2). Secreted acid phosphatases (sAP) also contain PGs, and other less abundant PG-containing molecules exist (3,4). Leishmania PG repeating units contain the disaccharide-phosphate [Gal(β1,4)-Man(α1)PO4] (referred to hereafter as PG repeat backbone) (5). Moreover, PGs frequently contain additional sugar substitutions in different species and strains, most commonly on the Gal residue although modifications of the Man also occur (Fig. 1) (6).

Figure 1. PG and LPG and PPG structures.

Schematic diagrams of the basic PG repeating unit (A) and LPG and PPG structures (B). The detailed structures of LPG and PPG, including the cap, linkages, and anomeric configurations, are described elsewhere (Turco and Descoteaux, 1992; Ilg, 2000). The GPI-anchored form of PPG is depicted, but other forms of PPG are similar regarding the PG structures. “X” refers to linear β1,3 linked galactose residue(s) that branch off the Gal-Man-PO4 repeating unit backbone (panel A). EtN, ethanolamine.

Leishmania PGs can be linked to the cell surface via glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor attachment, directly as in LPG or through attachment to the protein backbone in PPGs (Fig. 1). The basic LPG structure has four domains: a 1-alkyl-2-lyso-PI anchor, a heptasaccharide core consisting of Gal(α1,6)-Gal(α1,3)-Galf(β1,3)-[Glc(α1-PO4)6]-Man(α1,3)-Man(α1,4)-GlcN(α1,6), the poly-PG “backbone” consisting of [Gal(β1,4)-Man(α6)P] PG repeat units (average n~15–30), and terminates in an oligosaccharide cap (Fig. 1). In Leishmania major, LPG plays several roles in parasite survival, including control of parasite binding to the sand fly midgut wall, resistance to lysis by complement, protection from oxidative damage, and delaying phagolysosomal fusion (6–8). PPGs arise from a large gene family that encodes large proteins (>200 kD) containing Ser/Thr-rich regions to which PG repeating units are attached (9,10). PPGs occur in different forms, including membrane-bound PPG, filamentous PPG, and secreted PPG (9). These PG-containing molecules play roles in parasite transmission and virulence following sand fly biting, such as modulating macrophage immune functions (11–13). The role(s) of sAPs in parasite virulence are not well understood, as their levels are relatively low in L. major (14), and sAP null mutants in L. mexicana are virulent (15).

The assembly of Leishmania PG repeating units to form LPG and PPGs occurs in the Golgi apparatus (16–18). Nucleotide-sugar transporters (NSTs) transport cytoplasmically-synthesized nucleotide-sugars into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or Golgi lumen, where they are consumed in glycosylation reactions (19–22). A large number of NSTs have been identified and they now constitute a well characterized family of membrane proteins (20,23). Previously we showed that the Leishmania LPG2 gene encoded the Golgi GDP-Man transporter, one of the earliest NSTs identified, and the first multi-specific NST as it is additionally able to transport GDP-D-Ara and GDP-L-Fuc (17). lpg2− mutants in three species of Leishmania were completely devoid of PGs (24–26), however the consequences to parasite virulence differed greatly. Mutant lpg2− L. major were unable to survive within macrophages or to cause pathology (8) while lpg2− L. mexicana were able to survive and induce disease (26).

Because Golgi GDP-Man transport is required for PG synthesis, we hypothesized there would be a matching requirement for UDP-Gal transport as well. Loss of UDP-Gal transport in L. major should therefore render parasites PG-deficient and provide an additional tool to study PG function. Galactose is found in other surface glycoconjugates of trypanosomatids (18), such as the glycan head groups of Type II GIPLs and in GPI anchor side chains containing poly-N-acetyl-lactosamine (27), although this modification is not known to occur in Leishmania. The phenotype of galactose-deficient trypanosomes has been investigated previously through inactivation of UDP-glucose epimerase (28), a gene also found in Leishmania. Since our interests concerned the role of galactosylation reactions occurring within secretory compartments, our strategy focused on inactivation of UDP-Gal transport.

Thus it was necessary first to identify the parasite’s UDP-Gal transporters. Twelve candidate NST sequences were identified in the L. major genome, with five showing varying degrees of similarity to known UDP-Gal transporters, including two pseudogenes. Our data indicate that two candidates, LPG5A and LPG5B, both encode UDP-Gal transporters and are required for phosphoglycan synthesis in L. major, although their functions differ significantly. More limited studies of another candidate, HUT1L, suggest it may be the functional homolog of the ER UDP-Glc NST, shown recently to be important to the protein folding glucosylation/reglucosylation process (29,30).

Experimental Procedures

Cell culture, reagents, and transfection

Leishmania were grown at 26°C in M199 medium (USBiological, Swampscott, MA) containing 10% fetal calf serum and other supplements as described (31). Unless otherwise indicated, the wild-type (WT) L. major strain LV39 clone 5 (RHO/SU/59/P) was used (LV39). More limited studies were performed on L. major strains SD (MHOM/SN/74/SD) and Friedlin V1 (WHOM/IL/80/FN), whose genome was recently completed (32). L. major strains are closely related, showing on average less than 1% sequence divergence (33). L. mexicana (MNYC/BZ/1962/M379), and L. donovani (MHOM/SD/00/1S-2D) were also used.

Leishmania cells were transfected by electroporation using either a low-voltage (31) or high-voltage protocol (34). Following transfection, cells were allowed to grow 16–24 h in M199 medium with 10% fetal calf serum and then plated on semisolid media containing 1% Noble agar (Fisher). Individual colonies were picked and grown in liquid medium. Clones were maintained in selective medium and then removed from selection for one passage prior to experiments. Hygromycin B was from Calbiochem (now under EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), G418 was from BioWhittaker (now under Cambrex Bio Science, Walkersville, MD), puromycin powder was from Sigma, blasticidin was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), nourseothricin was from Werner BioAgents (Jena, Germany), and phleomycin was from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA).

α-32P-dCTP was from Perkin-Elmer (Boston, MA). UDP-[6-3H]-Gal and GDP-[6-3H]-Man were from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). The protease inhibitors leupeptin, AEBSF, and E-64 were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Other reagents not mentioned were from either Sigma or Fisher (Fairlawn, NJ). PCR was done using Taq polymerase (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) or Platinum Tag Hi Fidelity (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Oligonucleotide primers were purchased from IDT (Coralville, IA), and their sequences are described in Supplemental Results. Restriction enzymes were from New England Biolabs Inc. (Ipswich, MA). Standard methods for general molecular biological techniques including Southern blotting were used as described (35).

L. major constructs

Molecular manipulations are summarized in Table S1. Briefly, ORFs were amplified from L. major DNA and cloned into the unique BamH I site of the Leishmania expression vectors pXG(NEO) (B1288) or pXG(PHLEO) (B3324). For expression oligonucleotide primers (Table S2) added an optimal translation initiation sequence (CCACC) upstream of the ORF start codon. PCR products were directly cloned into the TA vector pGEM-Teasy™ (Promega, Madison, WI), sequenced, and then liberated with BamHI and inserted into Leishmania expression vectors. Where indicated, ORFs were liberated from pXG vectors with BamH I and cloned into the unique BamH I site of pCDNA3 (B1974, Table S1). pXG(NEO)-hUGT1-cHA (B5541) and pMKIT-hUGT1-cHA (B5034) were gifts from H. Segawa.

LPG5A allelic replacement constructs were made by inserting ORFS encoding hygromycin B (HYG) or puromycin (PAC) resistance between 0.95-kb 5′ and 3′ LPG5A flanking regions present in pBSK-LPG5Aflanks (B4748, Table S1), making pBSK-LPG5A-HYGKO (B5019) and pBSK-LPG5A-PACKO (B5020). Disruption constructs for LPG5B were made by inserting a 0.92-kb Xho I fragment from pXG(BSD) (B4098), which contains the DHFR-TS splice acceptor site and the BSD resistance gene, into the unique BsrG I site of pBSK-LPG5B (B5025) to make pBSK-LPG5B-BSDdisrupt (B5025, Table S1). A 1.9-kb Acc I/Xho I fragment from pXG(NEO) (B1288), which contains the DHFR-TS splice acceptor site and the NEO resistance gene, was cloned into the BsrG I site of pBSK-LPG5Bsubclone to make pBSK-LPG5B-NEOdisrupt (B5026, Table S1).

Mapping of the LPG5A splice acceptor site

Mapping of splice acceptor sites was accomplished using RT-PCR (36). FV1 RNA was prepared from exponentially growing parasites using Trizol (Roche) and used as a template to generate randomly primed cDNAs using Superscript II (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). A universal mini-exon primer (SMB936) was used in conjunction with oligonucleotide SMB1581 (Table S2) to amplify portions of gene-specific cDNAs from the pool of randomly primed cDNAs described above, using Taq polymerase (Roche). The single product was cloned into pGEM-Teasy™ (Promega, Madison, WI) and sequenced.

Generation of LPG5 mutants and add-back lines

Targeting fragments for LPG5A and LPG5B were liberated from their respective vectors and purified prior to transfection into L. major LV39. For single-gene mutants, two rounds of transfection were done to recover homozygous mutants and correct targeting was confirmed using Southern analysis. The names below follow the formal nomenclature for Leishmania (37). The Δlpg5A/Δlpg5A clonal strain A1 was chosen for biochemical analysis and is referred to as lpg5A−. The ^lpg5B/^lpg5B clonal strain A3 was chosen for biochemical analysis and is referred to as lpg5B−. To produce a strain targeted in both LPG5A and LPG5B, LPG5B was disrupted in the lpg5A− mutant. Clonal strain 2A-2, whose genotype Δlpg5A/Δlpg5A/^lpg5B/^lpg5B was confirmed by Southern analysis, is referred to as lpg5A−/5B−. Further details are discussed in Supplemental Results. Parasite strains were passed in vitro no more than six times (M1P6) before use.

Immunoblotting

Whole cell lysates from L. major promastigotes were prepared from exponential-growth or stationary-phase parasites in SDS sample buffer; 5 × 106 cell equivalents/lane were separated by discontinuous SDS-PAGE on 4% stacking and 12.5% resolving gels, and then electro-transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond-ECL, Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). Protein loading was assessed by staining with 5%/Ponceau S/1% glacial acetic acid (w/v) prior to Western analysis. Monoclonal antibody WIC79.3 (38) was used at a 1:1000 dilution; CA7AE (39) was used at a 1:1000 dilution. Secondary antibodies conjugated to peroxidase were from Amersham, and ECL reactions were conducted using Pierce or Perkin-Elmer (Boston, MA) chemiluminescence kits.

Heterologous expression

WT Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) and Lec8 cells (40,41) were from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and maintained in culture following ATCC recommendations. Lec8 cells were transformed using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) per manufacturer instructions. Transfectants were selected in medium containing 640 μg/mL G418; 5,000–10,000 stable transfectants were pooled and maintained in 300 μg/mL G418. Lec8 cells were transfected with constructs pCDNA3, pCDNA-LPG5A, pCDNA-LPG5B, pCDNA-HUT1L, and pMKIT-hUGT1-cHA to make the strains Lec8/pCDNA3 (hereafter referred to as Lec8/empty), Lec8/LPG5A, Lec8/LPG5B, Lec8/HUT1L, and Lec8/hUGT1, respectively.

Fluorescent lectin binding

MAA-FITC lectin binding (EY Labs, San Mateo, CA) was assessed by fluorescence microscopy and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Transfectants were removed from antibiotic selection for one passage prior to experiments. Cells grown on coverslips for IFA or scraped from flasks for FACS were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for one minute in 3.7% formaldehyde (v/v) in PBS and incubated for 1 h at 25°C in 20 or 40 μg/mL MAA-FITC in PBS. Cells were washed three times with PBS and visualized using an Olympus AX-70 microscope (Melville, NY) or a Becton-Dickinson FACSCalibur (San Jose, CA).

Purification and analysis of LPG

LPG was prepared from exponential- and stationary-phase parasites using previously described methods (42). To assess side chain modification, phosphoglycan repeating units were obtained by depolymerization of LPG using mild acid hydrolysis, dephosphorylated, and covalently labeled with either 8-aminonaphthalene-1,3,6-trisulfate (ANTS) or 1-aminopyrene-3,6,8-trisulfonate (APTS) and analyzed using fluorescence-assisted carbohydrate electrophoresis (FACE) and capillary electrophoresis (CE) (43).

The number of PG repeating units per LPG molecule was determined using two methods. The first method used gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (44). Briefly, the lipid anchor was cleaved by nitrous acid deamination, and the anhydromannose residue at the reducing end was further reduced with NaBH4 to produce a single anhydromannitol residue for each LPG molecule. The LPG was hydrolyzed with 2 N trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to release neutral monosaccharides and phosphorylated monosaccharides (mostly galactose 6-phosphate). The phosphorylated monosaccharides were removed by anion exchange chromatography then the neutral monosaccharides were acetylated before GC-MS. The ratio of mannose to anhydromannitol was calculated, which was adjusted to account for the mannose present in the LPG core and capping sugars, to determine the number of PG repeats present per LPG molecule. The second method utilized capillary electrophoresis (43). Purified LPG was treated with nitrous acid, NaBH4, and TFA as in the GC-MS method. The released monosaccharides were directly labeled with APTS, omitting acetylation, and separated on a Beckman P/ACE 5000 (Fullerton, CA). As with the GC-MS method described above, the ratio of Man to anhydromannitol was determined to estimate the number of PG repeating units per LPG molecule. WT LPG was used as a control in all experiments.

Results

Database mining for NST candidates

We used the BLAST algorithm to identify candidate NSTs in Leishmania Genome Project databases (45), focusing primarily on queries with proteins with experimentally confirmed NST activity. In the completed Leishmania major genome, twelve sequences showing similarity to one or more NSTs were found (Table 1). To prioritize those mostly likely to encode UDP-Gal transporters, we compared the candidate Leishmania NSTs with UDP-Gal transporters from humans, yeast and plants, as well as the GDP-Man transporter LPG2 and human YEA4 (Table 1).

Table 1.

NST candidates identified in the L. major strain Friedlin genome.

| BLAST P score vs. query sequencea | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Systematic IDb | Accession Number | H. sapiens UDP-Gal (hUGT1) | S. pombe HUT1 | A. thaliana UDP-Gal (AtUTR1) | H. sapiens YEA4 (UDP-GA) | L. major LPG2 GDP-Man | ORF (nt) | # amino acids | TM domainsc |

| LPG5A | LmjF24.0360 | AY491008 | 10−20 | NSd | NS | NS | NS | 1,350 e | 451 | 10 |

| LPG5B | LmjF18.0400 | AY491009 | 10−30 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 1,686 | 561 | 10 |

| (LPG5-like) | LmjF15.0840 f | AY491006 | 10−8 | NS | NS | NS | NS | ~1050 | pseudogene | N/a |

| HUT1L | LmjF22.1010 | AY491010 | NS | 10−13 | 10−15 | NS | NS | 1,623 | 580 | 5–13 |

| (LPG5-like) | LmjF15.1055 g | AY491007 | N/A | NS | NS | NS | NS | ~1334 | pseudogene | N/a |

| LPG2 |

LmjF34.3120

LmjF19.1490 |

CAJ08033 CAJ07245 |

NS | NS | NS | NS | query | 1,032 | 341 | 8–9 |

| LmjF19.1510 | CAJ07248 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 10−8 | 966 | 322 | 8–10 | |

| LmjF30.2680 | CAJ06589 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 10−6 | 978 | 325 | 9–10 | |

| LmjF18.1540 | CAJ04305 | NS | NS | NS | 10−25 | NS | 1089 | 363 | 7 | |

| LmjF36.0670 | CAJ09020 | NSh | NS | NS | NS | NS | 1389 | 463 | 7–10 | |

| LmjF07.0400 | CAJ07000 | NSi | NS | NS | NS | NS | 1833 | 611 | 8–10 | |

Sequence comparisons were done using the BLAST or Psi-blast algorithms (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/bl2seq/wblast2.cgi).

assigned by Leishmania Genome Project (LGP).

Transmembrane (TM) domains determined by submitting amino acid sequence to three different topology programs (Supplemental Results).

NS. No significant similarity.

LmjF24.0360 was assigned a start codon upstream leading to a predicted 600 amino acid ORF; however our results show that the correct ORF is 451 amino acids.

LmjF15.0840 is a pseudogene containing two internal stop codons, which were identified by both our and LGP sequence. In L. infantum it appears intact (LinJ15.0890) but it is absent in L. braziliensis.

LGP release 5.2 annotates this as ‘LmjF15.1055’ although it is located on chromosome 20. In L. infantum it appears intact (LinJ20.1080) but it is absent in L. braziliensis.

LmjF36.0670 showed relationship to members of the solute carrier 35 subfamily A3 in Psi-blast comparisons (p <10−58).

LmjF07.0400 showed relationship to members of the solute carrier 35 subfamily F5 in Psi-blast comparisons (p < 10−64).

Focusing first on those showing relationship to known UDP-Gal transporters, LmjF24.0360 and LmjF18.0400 showed similarity to human UDP-Gal transporter hUGT1 and other UDP-Gal transporters (29–38% identity, Table S3), but no significant similarity to S. pombe Hut1, A. thaliana AtUTR1, or LPG2 (Table 1, Table S3). These two Leishmania proteins were nearly as divergent from each other as they were to other UDP-Gal NSTs (26% vs. 29–38% amino acid identity; Table S3). LmjF22.1010 (HUT1L) showed similarity to the A. thaliana AtUTR1 (30% identity, Table S3), shown recently to be a UDP-Glc/Gal NST located within the ER (29), and to S. pombe HUT1 (27%), which has been associated with Golgi UDP-Gal uptake (46). LmjF15.0840 bore two internal stop codons (confirmed here), arguing that it was a pseudogene; otherwise it showed relationship to other UDP-Gal NSTs including LmjF24.0360 and LmjF18.0400. “LmjF15.1055” showed more than 95% nucleotide identity with LmjF24.0360 (LPG5A) and mapped between the unrelated genes LmjF20.1050 and LmjF20.1060. Our independent sequence revealed one in frame deletion, four frameshift mutations, 37 point mutations and seven internal stop codons, confirming that it was a pseudogene. Of the remaining NSTs, LmjF19.1490 was identical to LmjF19.1510, and along with LmjF30.2680, showed weak similarity to LPG2 (Tables 1, S3). LmjF18.1540 showed strongest relationship to the YEA4 NST family which includes UDP-GalNAc and UDP-glucuronic acid transporters (Table 1).

Two additional potential L. major NSTs were only detected using more sensitive Psi-Blast comparisons (Table 1). LmjF07.0400 showed relationship to members of solute carrier subfamily family 35F, whose functions have not been determined. LmjF36.0670 showed relationship to members of solute carrier family 35A including human SLC35A3 which mediates UDP-GlcNAc uptake (47,48).

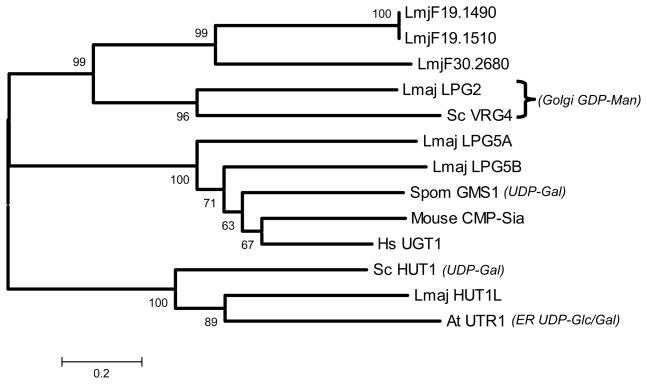

Phylogenetic analysis showed that the candidates LmjF24.0360 and LmjF18.0400 associated with other functionally characterized UDP-Gal transporters from Schizosaccharomyces pombe, plants and mammals (Fig. 2, Table S3, and data not shown). While encouraging, this cluster contained transporters with specificities for a variety of UDP-sugars as well as CMP-sialic acid transporters (23), reinforcing prior observations that phylogeny is of only limited usefulness in predicting nucleotide sugar specificity in the NST family (20,21,49). Nonetheless, we used evolutionary relationship as a guide to focus on the two candidates showing the best homology to hUGT1, which we named LPG5A and LPG5B (Table 1), and carried out limited studies on the HUT1 related gene LmjF22.1010, which we named HUT1L (HUT1-like).

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree of Leishmania NSTs.

This evolutionary tree depicts relationships amongst L. major NST candidates and key NSTs of known function. These include ScVRG4, Saccharomyces cerevisiae GDP-Man transporter (P40107), Schizosaccharomyces pombe GMS1, S. pombe UDP-Gal transporter (BAA24703), Mouse CMP-Sia transporter (CAA95855), human UGT1 UDP-Gal transporter (BAA12673), Arabidopsis thaliana AtrUTR1 ER UDP-Glc/Gal transporter (AAM48281), and the S. cerevisiae HUT1 transporter (Q12520). The scale represents amino acid substitutions. Amino acid sequences were aligned using the M-Coffee algorithm (71), which incorporates input from a number of pairwise and multiple alignment procedures and generates a consensus. Following removal of gap positions, a bootstrap consensus evolutionary tree was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining algorithm (1000 replicas) implemented in the MEGA 3.1 evolutionary analysis package (72). The smaller numbers above the nodes represent the bootstrap consensus percentages and are a measure of confidence. Tests of a variety of different alignment and tree algorithms did not reveal any significant differences within the major lineages depicted here (data not shown). A table of pairwise percent identities can be found in Table S3. Due to its greater evolutionary distance protein Lmj18.1540 was not included in this analysis. Database mining for L. infantum and L. braziliensis suggest that orthologs for the L. major genes depicted here are present in these species as well.

We identified orthologs for LPG5A, LPG5B, and HUT1L in the provisional genome sequences of L. infantum and L. braziliensis. Interestingly, seemingly intact orthologs for pseudogenes LmjF15.0840 and LmjF15.1055 were found in L. infantum (LinJ15.0890 and LinJ20.1080, respectively) but not L. braziliensis. We did not identify additional NSTs in these species beyond orthologs of those of L. major, although this conclusion is tentative since their genomes were not complete.

Properties of the LPG5A and LPG5B open reading frames

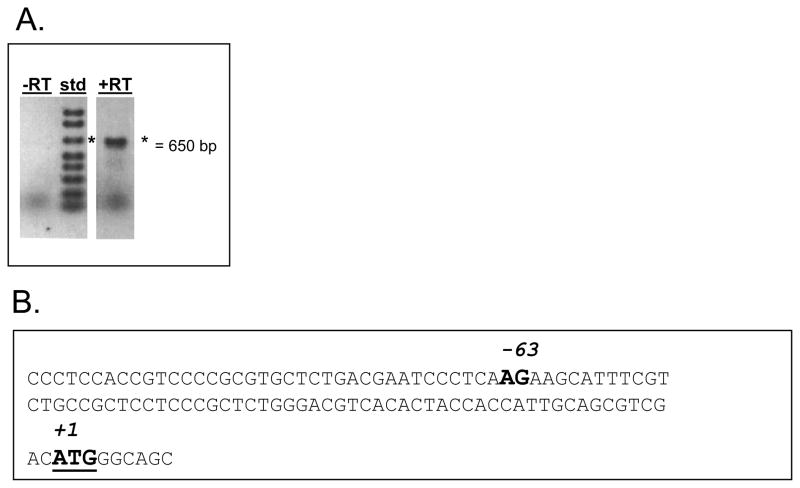

Typical eukaryotic NSTs are about 320–400 amino acids in length, however the predicted LPG5A and LPG5B proteins comprised 600 and 561 amino acids, respectively (Table 1). We mapped the 5′ end of the LPG5A mRNA using RT-PCR and the fact that all Leishmania mRNAs bear a common 39 nt 5′ leader sequence added by trans-splicing. This placed the splice acceptor at a position located 384 nt 3′ of the annotated AUG for the 600 amino acid LPG5A ORF (Fig. 3A). The next AUG following this mapped splice acceptor occurred 63 nt downstream (Fig. 3B), leading to a predicted LPG5A protein of 451 amino acids (Table 1). As shown below, the 451 amino acid LPG5A ORF was functional. While efforts to similarly map the LPG5B 5′ end were unsuccessful, current data suggest the 561 amino acid ORF for LPG5B is correct (discussed below).

Figure 3. mRNA mapping for LPG5A.

A. RT-PCR with the LPG5A-specific oligo SMB1581and the mini-exon specific primer SMB936 (Table S2) were used to amplify LPG5A-specific cDNA from a pool of L. major randomly generated cDNAs. Lanes not relevant to this experiment were removed. One RT-PCR reaction was done either in the absence of reverse transcriptase (-RT) or presence of reverse transcriptase (+RT). The “std” lane contains the 1KB+ marker (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA); the asterisk indicates the 650-bp marker. B. The PCR product from panel A was cloned into pGEM-Teasy™ and sequenced; from this the location of the splice acceptor was determined and this AG is shown (in bold) on the genomic DNA sequence of this region. The predicted LPG5A start codon (in bold) is located 63 nt 3′ of this splice acceptor.

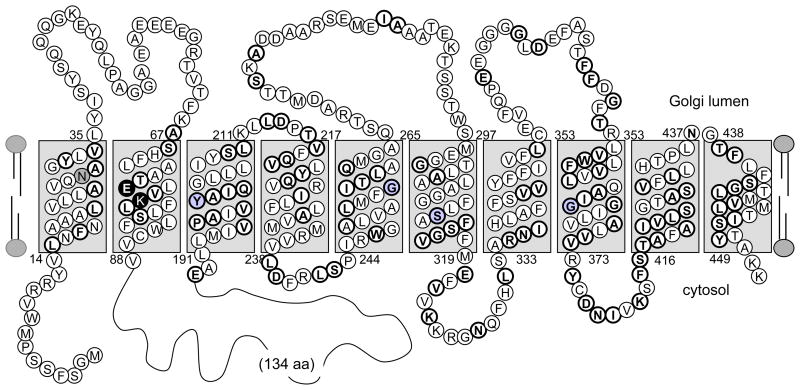

Several transmembrane (TM) prediction algorithms suggested the occurrence of 8–10 TM domains for both LPG5A and LPG5B, consistent with predictions for other NSTs (Table 1, Fig 4, Fig. S1). We incorporated previous studies of the murine CMP-sialic acid transporter, whose topology has been experimentally determined and whose sequence is closely related to UDP-Gal transporters (50). From this and sequence alignment criteria, we developed models predicting 10 transmembrane domains in the LPG5A and LPG5B proteins (Fig. 4, S1; Fig. S2 presents an amino acid alignment with shaded predicted TM domains).

Figure 4. Proposed topology for LPG5A.

A predicted topology for LPG5A is shown; a similar prediction for LPG5B is shown in Fig S1. This topology is based upon a synthesis of the results of a panel of TM prediction algorithms and the known topology of the mouse CMP-Sia transporter (50). Charged residues predicted to be buried in transmembrane domains are shaded black and conserved residues where inactivating mutations have been mapped in other NSTs are shaded gray. Residues with heavy outline are identical or similar with the murine CMP-Sia transporter. A large 134 amino acid cytoplasmic loop was identified between TM2 and TM3, whose full sequence is not shown.

One striking feature in both LPG5A and LPG5B was the prediction of a large cytoplasmic loop (134 and 199 amino acids, respectively) between TM domains 2 and 3 (Fig. 4, S1). For comparison, this loop is 25–26 amino acids in the mammalian UDP-Gal and CMP-Sia NSTs, and no other characterized NSTs to date bear a loop comparable to those of LPG5A or LPG5B. Other conserved features included several buried charged residues, including a conserved Glu and Lys residues in the second predicted TM2 domains of LPG5A, LPG5B, murine CMP-Sia and human UDP-Gal NSTs (Figs. 4, S1, S2). Residues shown to be functionally important in the mammalian UDP-Gal and CMP-Sia (21) were conserved in LPG5A and LPG5B as well (Figs. 4, S1, S2).

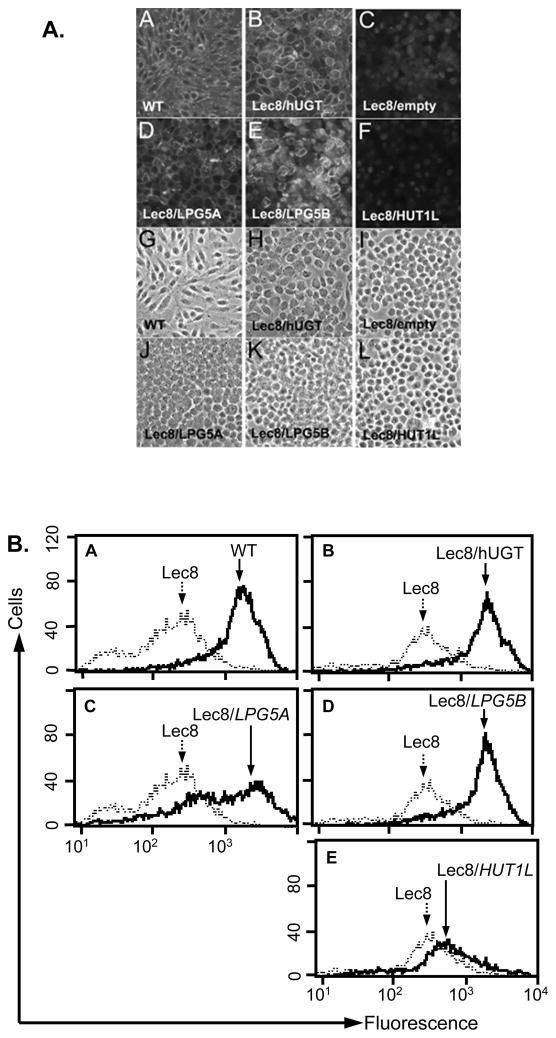

LPG5A and LPG5B rescue the glycosylation defect of the UDP-Gal NST deficient Lec8 mutant

To test the function(s) of the three UDP-Gal transporter candidates LPG5A, LPG5B, and HUT1L, we asked whether heterologous expression of these ORFs could rescue the CHO cell mutant Lec8. This mutant is deficient in UDP-Gal transport, leading to decreased glycoprotein galactosylation, deficiency in sialylation, and a failure to react with the sialic acid (α2,3)-galactose-specific Maackia amurensis (MAA) lectin (41,51). When a functional UDP-Gal transporter is expressed in these cells, MAA lectin binding is restored (52), a widely used assay to functionally identify and characterize UDP-Gal transporters from a variety of species (19,21,22).

MAA binding was examined in stably transfected Lec8 cells bearing constructs expressing LPG5A, LPG5B, or HUT1L. By fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5A) and flow cytometry (Fig. 5B), LPG5A and LPG5B transfectants showed strong MAA binding, similar to that of WT CHO cells or to Lec8 cells expressing the human UDP-Gal transporter hUGT1. A caveat to the negative HUT1L result is that a specific antiserum to HUT1L was not available, precluding verification of its correct expression and/or localization in the transfectants. These data suggested that LPG5A and LPG5B likely encoded proteins with UDP-Gal transporter activity.

Figure 5. LPG5A and LPG5B rescue MAA reactivity in the UDP-Gal transporter deficient Lec8 mutant.

Part A. Fluorescence microscopy. Panels A-F display the fluorescent images of cells stained with FITC labeled MAA lectin, panels G-L display the phase contrast images. Panel A, G: WT CHO cells. B, H: Lec8/hUGT1. C, I: Lec8/empty. D, J: Lec8/LPG5A. E, K: Lec8/LPG5B. F, L: Lec8/HUT1L. Part B. Flow cytometry. Stably transfected Lec8 CHO cells were fixed and incubated with FITC-labeled MAA lectin. In panels A-E, WT or transfected Lec8 cells (solid black lines) are shown compared to Lec8 transfected with empty vector (Lec8; dotted line). These data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Generation of null LPG5A, LPG5B and double mutants

To further study the candidate UDP-Gal transporters, we created null mutants. Leishmania are asexual and predominantly disomic, necessitating the use of two successive rounds of transfection to generate null mutants (53,54). For LPG5A we designed constructs that would precisely replace the 451 amino acid LPG5A ORF with drug resistance marker ORFs encoding hygromycin B (HYG) or puromycin (PAC) resistance (Fig. 6A). Starting with the WT LV39 strain of L. major, correct replacement of both alleles was confirmed by Southern analysis (Fig. 6C), and this mutant is termed lpg5A−.

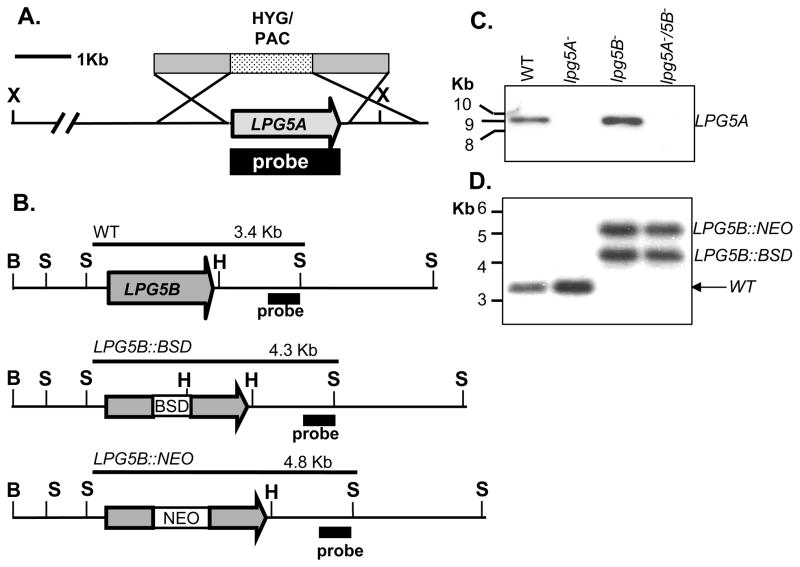

Figure 6. Inactivation of LPG5A and LPG5B.

A. Allelic replacement strategy for LPG5A. The HYG/PAC targeting fragment is shown above the map of the LPG5A locus. Predicted restriction fragments and the probe used for Southern analysis in panel C are indicated. B. Insertional inactivation strategy used for LPG5B. In this experiment the targeting fragment (not shown) consists of the LPG5B ORF into which autonomous BSD or NEO selectable markers were inserted (Methods). Predicted restriction fragments and the probe used for Southern blotting in panel D are indicated (bold lines). In both analyses, the probe used for Southern analysis (Methods) lay outside the targeting fragment as shown. X, Bg, Bs, H, and S indicate Xho I, Bgl II, BsrG I, Hind III, and Sal I sites, respectively. C. Autoradiogram following Southern analysis of the LPG5A locus in WT and mutants; DNA was digested with XhoI and the probe used is shown in panel A. D. Autoradiogram following Southern analysis of LPG5B locus in WT and mutants; DNA was digested with SalI and the probe used is shown in panel B.

For LPG5B, we were unable to determine the mRNA start site by RT-PCR using a variety of LPG5B specific primers and amplification conditions (data not shown); the reasons for this are not evident to us. The assignment of the LPG5B ORF, however, was supported by functional assays (Fig. 5), sequence alignment (Fig. S2), and transfection assays showing that several shorter ORFs initiating at downstream AUGs were inactive (data not shown). Thus for LPG5B an insertional inactivation approach was used where autonomous drug resistance cassettes mediating resistance to blastocidin (BSD) and G418 (NEO) were inserted into the LPG5B ORF (Fig. 6B). Correct targeting was confirmed by Southern analysis (Fig. 6D) and this mutant was designated lpg5B−. To make the lpg5A−/5B− mutant, we inactivated LPG5B in the background of the lpg5A− mutant above. Successful alteration of both genes was confirmed by Southern analysis (Fig. 6C, D). All mutants grew at normal rates and to normal densities in standard M199 culture media in vitro (data not shown).

LPG5A or LPG5B are sufficient for PG synthesis but the lpg5A−/B− mutant lacks PGs

L. major PG repeats are often modified by side chain Gal residues, added in consecutive β1,3 linkages to the Gal residue within the PG repeating unit by specific Gal-transferases (Fig. 1) (55). Gal-modified PG repeats can be recognized by the monoclonal antibody WIC79.3 (56), while unmodified PG repeats can be recognized by monoclonal antibody CA7AE (39). We used these in immunoblotting to probe the effects of LPG5A and LPG5B mutations on PG synthesis; similar results were obtained by immunofluorescence microscopy (data not shown).

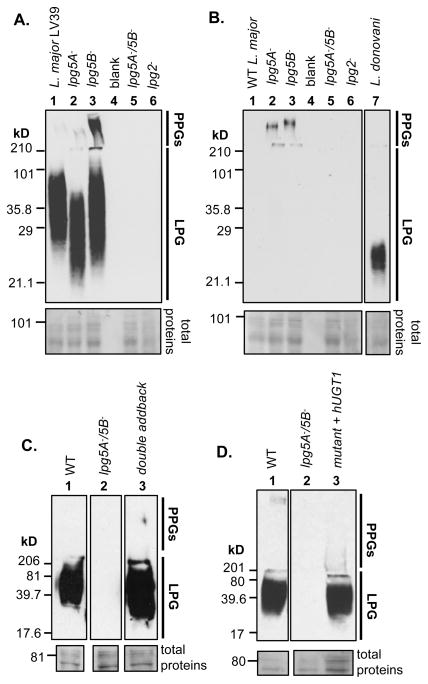

WT extracts showed strong reactivity to WIC79.3 in the 25 – 100 kD region, corresponding to LPG, while a much fainter reactivity was observed within the stacking gel, where the large PPGs migrate under these conditions (Fig. 7A, lane 1) (7,10). In the lpg5A− mutant, strong WIC79.3 reactivity remained, but migrated faster with an apparent MW of 20–40 kD (Fig. 7A, lane 2). A slight increase in WIC79.3 reactivity in the stacking gel/PPG region was also observed (Fig. 7A, lane 2). In contrast, for the lpg5B− mutant strong WIC79.3 reactivity in the 25–100 kD “LPG region” remained, while greatly elevated reactivity was observed within the stacking gel/“PPG region” (Fig. 7A, lane 3). These data suggested that loss of LPG5A primarily affected PGs associated with LPG, whereas loss of LPG5B primarily affected PGs associated with PPG.

Figure 7. LPG5A and LPG5B are required for PGs.

Whole cell lysates were probed by immunoblotting (Methods). Portions of the membranes after staining with Ponceau are shown to indicate protein loading. A. Immunoblotting with anti-galactosylated PG antibody WIC79.3. Lane 1: WT; lane 2: lpg5A−; lane 3: lpg5B−; lane 4: empty; lane 5: lpg5A−/5B−; lane 6: lpg2−. Loss of LPG5A resulted in LPG that migrates faster in SDS-PAGE, while loss of LPG5B results in increased reactivity with WIC79.3 in the PPGs. Inactivating both LPG5A and LPG5B rendered L. major PG-deficient. B. Immunoblotting with antibody CA7AE, which recognizes unmodified PGs. Loss of LPG5A or LPG5B leads to a small increase in unmodified PGs in the PPG fraction, while the lpg5A−/5B− mutant lacks unmodified PGs. Lane 1, WT; lane 2, lpg5A−; lane 3, lpg5B−; lane 4, empty; lane 5, lpg5A−/5B−; lane 6, lpg2−; lane 7, L. donovani (Ld) Intervening lanes not related to this experiment were removed. C. PGs are rescued in the lpg5A−/5B− mutant following expression of LPG5A and LPG5B. Immunoblotting with WIC79.3. Lane 1, WT; lane 2, lpg5A−/5B−; lane 3, lpg5A−/5B−/+LPG5A/+LPG5B (double add-back). D. PGs are rescued in the lpg5A−/5B− mutant following expression of the human UDP-Gal transporter. Immunoblotting with WIC79.3. Lane 1, WT; lane 2, lpg5A−/5B−; lane 3, lpg5A−/5B−/+pXG-hUGT1. Note: intervening lanes on the same gel/blot not related to these experiments were digitally removed.

Both the lpg5A− and lpg5B− mutant showed a small increase in CA7AE reactivity in the stacking gel/PPG region (Fig 7B, lanes 2–3 vs, lane 1). This was consistent with the idea that loss of UDP-Gal NST activity leads to decreased levels of galactosylated PGs. The lpg5B− PPG showed slightly decreased mobility relative to that of lpg5A− (Fig. 7B, lanes 2, 3). The significance of this observation is uncertain as structural studies of the PPG were not undertaken; potentially, the CA7AE-reactive PPG population is a minor fraction of total PPGs.

In contrast to the single mutants, no reactivity with either monoclonal antibody was seen for the double lpg5A−/5B− mutant, in either the LPG or stacking gel/PPG regions (Figs. 7A,7B, lanes 5). This phenotype was identical to that seen in the lpg2− mutant (Fig. 7A, B, lanes 6), which is completely deficient in PGs through loss of the GDP-Man transporter (17). Thus, lpg5A−/5B− had similarly completely lost PG synthesis. PG expression was restored by reintroduction of either LPG5A or LPG5B, singly (data not shown) or in combination (Fig. 7C).

Altered LPG structure in lpg5A− but not lpg5B− mutants

The altered mobility of lpg5A− LPG (Fig. 7A, lane 2) suggested it was structurally altered, presumably arising through decreased levels of galactosylation. This could arise through decreased numbers of PG side chain Gal residues or PG repeats, or both (Fig. 1A). We thus purified LPG from WT and mutant strains, and determined its structure (Table 2). Side-chain galactosylation was assessed by depolymerizing LPG with mild acid to release the PG repeating units, which were then separated by capillary electrophoresis and quantitated. To examine the number of PG repeats in the LPG backbone of the lpg5A− mutant, we measured the ratio of mannose to anhydromanitol, the former arising from the PG repeats and the latter from the LPG core, following removal of the lipid anchor by nitrous acid deamination and reduction with NaBH4, and hydrolysis to monosaccharides (Methods).

Table 2.

Biochemical analysis of WT and mutant LPGs.

| Side-chain Gal/PG Repeat | Fraction PG repeats unmodified | PG Repeat Units/LPG | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth phase\Cell Line | Log | Stat | Log | Stat | Log | Stat |

| WT | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 0.17 ± 0.15 | 18.2 | 19.8 |

| lpg5A − | 1.2 ± 0.4** | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.40 ± 0.08** | 0.47 ± 0.11 | 13.5* | 10** |

| lpg5B − | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 21 | 23 |

Significantly different from WT at the p < 0.05 level by a t-test of means.

Significantly different from WT at the p < 0.10 level.

Values shown are averages ± standard deviation. For PG repeat compositions, N=4 for WT and N=2 for lpg5A− and lpg5B− determinations. For PG repeat unit number determinations, a single analysis was done. The GC-MS method was used for lpg5A− and the CE method was used for lpg5B− (Methods); both were used for WT, where they agreed well (18.2 ± 1.9 and 19.8 ± 0.2 for WT log and stationary phase, respectively). Statistical comparisons for the PG Repeat Units/LPG used these values

For lpg5A− LPG, a general decrease in both types of galactosylation was seen (Table 2). The fraction of PG repeats lacking Gal side chains was 3–4 fold higher (0.40 vs 0.09 WT in log phase), and 43% fewer Gal residues per PG repeat were added. Moreover, the number of lpg5A− PG repeats was reduced to 50–74% of WT (13.5 and 10 vs 18.2 and 19.8 for WT log and stationary phase LPG, respectively). In contrast, LPG from the lpg5B− mutant closely resembled that of WT, in both the number of side chain Gal residues/PG repeat, the fraction of unmodified PG repeats, and the total number of repeats (Table 2). These results were consistent with the immunoblot analysis (Fig. 7). Thus, loss of LPG5A, but not LPG5B, resulted in a general deficit in LPG galactosylation, affecting both side chain and PG repeat galactosylation quantitatively, to about the same extent.

Loss of LPG5B primarily affects PPG modification

While LPG was unaffected by loss of LPG5B, PPGs in the lpg5B− but not lpg5A− mutant reacted much more strongly with antibody WIC79.3 (Fig. 7A, lanes 1–3). This gain seemed contrary to the expectation that loss of a UDP-Gal transporter would lead to a deficit in some aspect of PG galactosylation, which might lead to a loss (or perhaps no change) in WIC79.3 reactivity. However, if WIC79.3 were more strongly reactive with PG repeats bearing fewer side chain Gal residues, increased reactivity could arise by an increased level of mono-galactosylated PG repeats, at the expense of poly-galactosylated PG repeats. The epitope specificity of WIC79.3 was previously examined by galactosyl-ligand inhibition studies (38). To assess the specificity of WIC79.3 in the context of intact LPG, a series of parasite lines expressing LPGs showing a range of side chain PG galactosylation were studied. As shown in the Supplementary Results, when tested against intact LPG or PPG in western blotting, monoclonal antibody WIC79.3 shows a strong preference for mono-galactosylated PG repeats, reacting poorly with oligo-galactosylated PG repeats and not at all with poly-galactosylated PG repeats (Fig. S3). This matches the finding that the LPG present in the immunogen for WIC79.3 was probably mono-galactosylated LPG (38).

Thus the immunoblotting results are explicable as follows: the much greater reactivity of PPGs with WIC79.3 in the lpg5B− mutant can be attributed to increased levels of mono-galactosylated PG repeats, relative to WT PPGs which bear predominantly oligo/poly-galactosylated PG repeats. Thus loss of LPG5B appears to result in a decrease in galactosylation, but specifically affecting PPGs and not LPG (Table 1), in contrast to loss of LPG5A where the reverse is seen.

The lpg5A−/5B− mutant is rescued by expression of a heterologous UDP-Gal transporter

Attempts to demonstrate decreased UDP-Gal uptake with purified lpg5A−/B− microsomes were unsuccessful (Supplementary Results). This raised the formal possibility that the PG deficiency of the lpg5A−/5B− mutant might arise through mechanisms other than decreased UDP-Gal uptake. If this idea were correct, we reasoned that expression of a distantly related heterologous UDP-Gal transporter would be unable to rescue PG synthesis. Thus we expressed the human UDP-Gal transporter hUGT1 in the lpg5A−/5B− mutant. However, in these transfectants, WIC79.3 reactive LPG was restored fully (Fig. 7D, lane 3 vs lane 1). It is highly unlikely that hUGT1 expression would rescue PG synthesis by any mechanism other than restoration of UDP-Gal uptake, and thus we conclude that the PG deficiency of the lpg5A−/B− double mutant arises from a lack of UDP-Gal transport activity.

Discussion

LPG5A and LPG5B encode UDP-Gal transporters required for L. major phosphoglycan synthesis

Twelve NST candidate sequences were identified in the L. major genome by database mining. Of these, LPG5A, LPG5B, and HUT1L showed evolutionary relationship to NSTs able to transport UDP-Gal in other species (Fig. 2). Since NST phylogeny does not always reflect substrate specificity (21,23,49), we tested these three candidates in functional assays. Expression of both LPG5A and LPG5B, but not HUT1L, could rescue MAA-lectin binding in UDP-Gal transport-deficient Lec8 cells (Fig. 5). While L. major mutants inactivated in either LPG5A or LPG5B still made PGs, we found that a mutant genetically defective in both LPG5A and LPG5B lacked detectable PGs (Fig. 7), and that PG levels were restored by re-expression of either (or both) of these genes (Fig. 7), but not by overexpression of HUT1L (data not shown). We were unable to measure UDP-Gal uptake in purified Leishmania microsomes using methods applied successfully previously to the LPG2 Golgi GDP-Man transporter, possibly due to the presence of a strong interfering galactosylation activity, whose source was not identified (Supplementary Information). Thus to confirm that the loss of PG synthesis in the lpg5A−/B− mutant arose specifically from a lack of UDP-Gal NST activity, we introduced the human UDP-Gal NST hUGT1, which completely restored PG synthesis. Together, these data indicate that LPG5A and LPG5B both encode UDP-Gal transporters, whose combined inactivation results in loss of PGs in L. major.

From the structures of known Leishmania glycoconjugates, one could predict that in addition to GDP-Man and UDP-Gal, NSTs mediating uptake of UDP-Glc, GDP-D-Arabinopyranose, and UDP-Galactosfuranose are required. Many NSTs are multispecific and able to transport more than one nucleotide sugar, such as LPG2 which can transport GDP-Ara and GDP-Fuc in addition to GDP-Man (17,23,57). Since UDP-Glc epimerase is localized to the glycosome in trypanosomatids (58), potentially UDP-Gal transport from this compartment may depend upon genes in the NST family.

The LPG5A/5B-related group of Leishmania NSTs appears to be a dynamic area of evolutionary variation, with the occurrence of at least two pseudogenes in L. major (Table 1), both of which may encode a functional gene in L. infantum (LinJ15.0890 and LinJ20.1080) but apparently not in L. braziliensis. Moreover, the NST gene families of Trypanosoma brucei and T. cruzi appear to be as complex and diverse as seen in Leishmania (www.genedb.org; data not shown). Of the remaining NSTs, several showed distant relationship to the LPG2 GDP-Man transporter (LmjF19.1490/19.1510 and LmjF30.2680) and one showed relationship to the YEA4 group of NSTs which includes UDP-Glucuronic acid/UDP-GalNAc transporters (LmjF15.0840).

Orthogologous genes related to LmF36.0670 were restricted to Leishmania species, while an ortholog of LmjF07.0400 was present in T. brucei but not T. cruzi, and ones related Lmj19.1490/19.1510 occurred in the T. cruzi, but not T. brucei genomes. Potentially these NSTs could be redundant, have specificities for nucleotide sugars required uniquely by each species, or act in distinct cellular compartments. One attractive role for NSTs shared by L. major and T. cruzi involves UDP-Galactofuranose, since UDP-galactopyranose mutase, the enzyme responsible for UDP-Galf synthesis, is absent in the T. brucei genome (59). Correspondingly, Leishmania and T. cruzi, but not T. brucei, synthesize a variety of Galf containing glycoconjugates (see references cited in (59)).

A probable role for Leishmania HUT1L as an ER UDP-Glc NST

Leishmania HUT1L was of interest since its closest relatives mediate UDP-Gal uptake in other species (30). However, heterologous expression of HUT1L did not rescue the UDP-Gal transport defect of Lec8 cells (Fig. 5). In preliminary studies, we attempted to generate null mutants for Leishmania HUT1L with the same methods successful with LPG5A and LPG5B (Fig. 6; data not shown). While heterozygous replacements were readily obtained, we were unable to obtain homozygous null mutants (data not shown). Instead a variety of aneuploid and tetraploid cell lines were recovered bearing the second replacement as well as the WT gene (data not shown), a common finding in other studies in Leishmania attempting to knockout essential genes (60).

Recently it was shown that the Arabidopsis HUT1L relative AtUTr1 encodes a UDP-Glc/Gal NST activity localized to the ER (29), as do fungal HUT1s (30). Interestingly, both HUT1L and AtUTr1 bear a C-terminal lysine-rich motif implicated in ER localization (61). Within the ER, AtUTr1 participates in the unfolded protein response, through provision of ER UDP-Glc required for the glucosylation/glucosidase cycle occurring as part of protein folding and quality control (29,62,63). Were Leishmania HUT1L similarly involved in the protein folding cycle in Leishmania, its loss could prove lethal to the cell, since unlike other organisms, the core glycans added to nascent trypanosomatid glycoproteins lack Glc residues and must necessarily be acquired in the ER (64). Preliminary data show localization of a GFP tagged HUT1L protein to the Leishmania ER2, and thus we believe that Leishmania HUT1L may likely be the parasite’s ER UDP-Glc transporter. Functional studies will be required in the future to confirm the specificity of this and other novel NSTs identified here.

LPG5A and LPG5B show functional divergence

While complete ablation of PG synthesis required inactivation of both LPG5A and LPG5B, both the single lpg5A− and lpg5B− mutants made abundant PGs, albeit with different phenotypes. For the lpg5A− mutant, a structurally altered LPG was made (Fig. 7A), containing less side chain galactosylation and fewer PG repeating units (Table 2), but alterations in PPG immunoreactivity were not detected. In contrast, the structure of LPG was unchanged in the lpg5B− mutant (Table 2), but alterations in PPG immunoreactivity were seen (Fig. 7A). These was attributed to decreased galactosylation, leading to an increase in WIC79.3-reactive mono-galactosylated PGs at the expense of oligo or poly-galactosylated PGs linked to PPG (Figs. 7, S3).

What underlies the functional differences between LPG5A and LPG5B? Some NSTs display specific interactions with glycosyltransferases, as in the case of the mammalian Golgi UDP-galactose transporter UGT1 with UDP-galactose:ceramide galactosyltransferase (65). Building upon this model, perhaps key Gal transferases responsible for LPG vs. PPG PG synthesis preferentially association with the LPG5A and LPG5B UDP-Gal NSTs, respectively. Another possibility invokes differential localization within the secretory pathway of LPG5A and LPG5B. Current data strongly indicate that PGs incorporated into both LPG and PPG are synthesized in the parasite Golgi apparatus (16–18,26). While it has been generally assumed that relevant NSTs and glycosyltransferases are colocalized in the same compartment, recent data also raise the possibility that lumenal nucleotide-sugars may traffic between compartments as well (66,67). Moreover, considerable data point to the existence of functionally divergent subcompartments within and after the eukaryotic Golgi apparatus (68). Either model above could explain why, despite some degree of functional separation, both LPG5A and LPG5B function must be lost in order to completely ablate PG synthesis. For the association model, the coupling could be leaky, and for the compartmentalization, anterograde and/or retrograde vesicular trafficking of lumenal UDP-Gal could result in limited redistribution.

The structure of the LPG5A and LPG5B proteins themselves provide some opportunities for functional divergence. While most features closely resemble those of other known NSTs, LPG5A and LPG5B are unique in possessing a large, divergent 134–199 amino acid insert between the second and third TM domains (Fig. 4, Fig. S1). Moreover, the C-terminal domain of several NSTs has been implicated in targeting NSTs to the ER and/or Golgi apparatus, through both dilysine retention and/or hydrophobic export motifs (66,69,70). Both LPG5A and LPG5B show potential motifs of this sort (Fig. S2). Thus it is reasonable to propose that these or other domains contribute in some way towards divergent functions of these two NSTs. Preliminary data suggest that at least some portion of C-terminally tagged LPG5A and LPG5B proteins are found within the parasite Golgi apparatus, and efforts are underway to more finely map the cellular distribution of these two proteins and the functional roles of the unique peptide insert domains in both LPG, PPG and other secretory pathway glycoconjugates such as the glycosylinositolphospholipids or GIPLs 3.

In summary, we have presented data for the existence of multiple NST candidate sequences in L. major. Pursuant to our interests in UDP-Gal transport, we found two functionally divergent UDP-Gal transporters, LPG5A and LPG5B, which both contribute to PG synthesis in L. major. These two NSTs show novel structural features and properties, studies of which are likely to increase our knowledge of the detailed Leishmania PG synthetic and secretory pathway in the future. Given the evolutionary diversity of glycoconjugates in both Leishmania and trypanosomes, and their key roles during their infectious cycles, our studies further emphasize the roles of the large and diverse NST family in these important pathogens. 4

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations used are: PG, phosphoglycan; PPG, proteophosphoglycans; GIPL, glycosylinositolphospholipid; Gal, galactose; Man, mannose; LPG, lipophosphoglycan; NST, nucleotide-sugar transporter; UDP-Gal, uridine diphosphogalactose; GDP-Man, guanine diphosphomannose; Galf, galactofuranose; GDP-Ara, guanine diphosphoarabinose; GDP-Fuc, guanine diphosphofucose, UGT, UDP-Gal transporter.

T. Nicholson, A. Capul, and S. M. Beverley, unpublished.

A. Capul, T. Nicholson, F. Hsu, J. Turk, S.J. Turco and S.M. Beverley, in preparation.

We thank T. Nicholson for preliminary data concerning Hut1L localization in Leishmania, E. Handman for providing anti-PPG antisera, and T. Doering, D. Goldberg, W. Goldman, S. Kornfeld, T. Nicholson, L.D. Sibley, and members of the Beverley Laboratory for helpful discussion and comments. Supported by NIH grant AI31078 to SMB and SJT.

References

- 1.Naderer T, Vince JE, McConville MJ. Curr Mol Med. 2004;4:649–665. doi: 10.2174/1566524043360069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turco SJ, Descoteaux A. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1992;46:65–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.000433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gottlieb M, Dwyer DM. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:76–81. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiese M, Ilg T, Lottspeich F, Overath P. EMBO J. 1995;14:1067–1074. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turco SJ, Hull SR, Orlandi PA, Jr, Shepherd SD, Homans SW, Dwek RA, Rademacher TW. Biochemistry. 1987;26:6233–6238. doi: 10.1021/bi00393a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sacks DL. Cell Microbiol. 2001;3:189–196. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spath GF, Epstein L, Leader B, Singer SM, Avila HA, Turco SJ, Beverley SM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9258–9263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160257897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spath GF, Garraway LA, Turco SJ, Beverley SM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9536–9541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530604100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ilg T. Parasitol Today. 2000;16:489–497. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(00)01791-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montgomery J, Curtis J, Handman E. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;121:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers ME, Ilg T, Nikolaev AV, Ferguson MA, Bates PA. Nature. 2004;430:463–467. doi: 10.1038/nature02675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piani A, Ilg T, Elefanty AG, Curtis J, Handman E. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:589–599. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)80058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters C, Kawakami M, Kaul M, Ilg T, Overath P, Aebischer T. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2666–2672. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shakarian AM, Dwyer DM. Exp Parasitol. 2000;95:79–84. doi: 10.1006/expr.2000.4511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiese M. EMBO J. 1998;17:2619–2628. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.9.2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bates PA, Dwyer DM. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1987;26:289–296. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(87)90081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma D, Russell DG, Beverley SM, Turco SJ. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3799–3805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McConville MJ, Mullin KA, Ilgoutz SC, Teasdale RD. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:122–154. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.1.122-154.2002. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berninsone PM, Hirschberg CB. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:542–547. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Handford M, Rodriguez-Furlan C, Orellana A. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39:1149–1158. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2006000900002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerardy-Schahn R, Oelmann S, Bakker H. Biochimie. 2001;83:775–782. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawakita M, Ishida N, Miura N, Sun-Wada G, Yoshioka S. Journal of Biochemistry. 1998;123:777–785. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez-Duncker I, Mollicone R, Codogno P, Oriol R. Biochimie. 2003;85:245–260. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(03)00046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Descoteaux A, Luo Y, Turco SJ, Beverley SM. Science. 1995;269:1869–1872. doi: 10.1126/science.7569927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spath GF, Lye LF, Segawa H, Sacks DL, Turco SJ, Beverley SM. Science. 2003;301:1241–1243. doi: 10.1126/science.1087499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ilg T, Demar M, Harbecke D. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4988–4997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Treumann A, Zitzmann N, Hulsmeier A, Prescott AR, Almond A, Sheehan J, Ferguson MA. J Mol Biol. 1997;269:529–547. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roper JR, Guther ML, Milne KG, Ferguson MA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5884–5889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092669999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reyes F, Marchant L, Norambuena L, Nilo R, Silva H, Orellana A. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9145–9151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512210200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakanishi H, Nakayama K, Yokota A, Tachikawa H, Takahashi N, Jigami Y. Yeast. 2001;18:543–554. doi: 10.1002/yea.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kapler GM, Coburn CM, Beverley SM. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1084–1094. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.3.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivens AC, Lewis SM, Bagherzadeh A, Zhang L, Chan HM, Smith DF. Genome Res. 1998;8:135–145. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beverley SM, Ismach RB, Pratt DM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:484–488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson KA, Beverley SM. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;128:217–228. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(03)00079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dobson DE, Scholtes LD, Valdez KE, Sullivan DR, Mengeling BJ, Cilmi S, Turco SJ, Beverley SM. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15523–15531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clayton C, Adams M, Almeida R, Baltz T, Barrett M, Bastien P, Belli S, Beverley S, Biteau N, Blackwell J, Blaineau C, Boshart M, Bringaud F, Cross G, Cruz A, Degrave W, Donelson J, El-Sayed N, Fu G, Ersfeld K, Gibson W, Gull K, Ivens A, Kelly J, Vanhamme L, et al. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;97:221–224. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelleher M, Bacic A, Handman E. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:6–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tolson DL, Turco SJ, Beecroft RP, Pearson TW. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989;35:109–118. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stanley P. Mol Cell Biol. 1981;1:687–696. doi: 10.1128/mcb.1.8.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deutscher SL, Hirschberg CB. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Orlandi PA, Jr, Turco SJ. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10384–10391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barron TL, Turco SJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760:710–714. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahoney AB, Sacks DL, Saraiva E, Modi G, Turco SJ. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9813–9823. doi: 10.1021/bi990741g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ivens AC, Peacock CS, Worthey EA, Murphy L, Aggarwal G, Berriman M, Sisk E, Rajandream MA, Adlem E, Aert R, Anupama A, Apostolou Z, Attipoe P, Bason N, Bauser C, Beck A, Beverley SM, Bianchettin G, Borzym K, Bothe G, Bruschi CV, Collins M, Cadag E, Ciarloni L, Clayton C, Coulson RM, Cronin A, Cruz AK, Davies RM, De Gaudenzi J, Dobson DE, Duesterhoeft A, Fazelina G, Fosker N, Frasch AC, Fraser A, Fuchs M, Gabel C, Goble A, Goffeau A, Harris D, Hertz-Fowler C, Hilbert H, Horn D, Huang Y, Klages S, Knights A, Kube M, Larke N, Litvin L, Lord A, Louie T, Marra M, Masuy D, Matthews K, Michaeli S, Mottram JC, Muller-Auer S, Munden H, Nelson S, Norbertczak H, Oliver K, O’Neil S, Pentony M, Pohl TM, Price C, Purnelle B, Quail MA, Rabbinowitsch E, Reinhardt R, Rieger M, Rinta J, Robben J, Robertson L, Ruiz JC, Rutter S, Saunders D, Schafer M, Schein J, Schwartz DC, Seeger K, Seyler A, Sharp S, Shin H, Sivam D, Squares R, Squares S, Tosato V, Vogt C, Volckaert G, Wambutt R, Warren T, Wedler H, Woodward J, Zhou S, Zimmermann W, Smith DF, Blackwell JM, Stuart KD, Barrell B, Myler PJ. Science. 2005;309:436–442. doi: 10.1126/science.1112680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kainuma M, Chiba Y, Takeuchi M, Jigami Y. Yeast. 2001;18:533–541. doi: 10.1002/yea.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guillen E, Abeijon C, Hirschberg CB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7888–7892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ishida N, Yoshioka S, Chiba Y, Takeuchi M, Kawakita M. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1999;126:68–77. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berninsone P, Eckhardt M, Gerardy-Schahn R, Hirschberg CB. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12616–12619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eckhardt M, Gotza B, Gerardy-Schahn R. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8779–8787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang WC, Cummings RD. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:4576–4585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miura N, Ishida N, Hoshino M, Yamauchi M, Hara T, Ayusawa D, Kawakita M. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1996;120:236–241. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cruz A, Coburn CM, Beverley SM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:7170–7174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beverley SM. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:11–19. doi: 10.1038/nrg980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dobson DE, Mengeling BJ, Cilmi S, Hickerson S, Turco SJ, Beverley SM. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28840–28848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Ibarra AA, Howard JG, Snary D. Parasitology. 1982;85 (Pt 3):523–531. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000056304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hong K, Ma D, Beverley SM, Turco SJ. Biochemistry. 2000;39:2013–2022. doi: 10.1021/bi992363l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roper JR, Guther ML, Macrae JI, Prescott AR, Hallyburton I, Acosta-Serrano A, Ferguson MA. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19728–19736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beverley SM, Owens K, Showalter M, Griffith C, Doering T, Jones V, McNeil M. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005 doi: 10.1128/EC.4.6.1147-1154.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cruz AK, Titus R, Beverley SM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1599–1603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andersson H, Kappeler F, Hauri HP. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15080–15084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.15080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parodi AJ. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:69–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parodi AJ. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1998;31:601–614. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x1998000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parodi AJ. Glycobiology. 1993;3:193–199. doi: 10.1093/glycob/3.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sprong H, Degroote S, Nilsson T, Kawakita M, Ishida N, van der Sluijs P, van Meer G. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3482–3493. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-03-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kabuss R, Ashikov A, Oelmann S, Gerardy-Schahn R, Bakker H. Glycobiology. 2005;15:905–911. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwi085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.D’Alessio C, Trombetta ES, Parodi AJ. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22379–22387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Puthenveedu MA, Linstedt AD. Current opinion in cell biology. 2005;17:369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao W, Chen TL, Vertel BM, Colley KJ. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31106–31118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605564200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roy SK, Chiba Y, Takeuchi M, Jigami Y. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13580–13587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wallace IM, O’Sullivan O, Higgins DG, Notredame C. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1692–1699. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. Brief Bioinform. 2004;5:150–163. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ryan KA, Dasgupta S, Beverley SM. Gene. 1993;131:145–150. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90684-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Akopyants NS, Clifton SW, Martin J, Pape D, Wylie T, Li L, Kissinger JC, Roos DS, Beverley SM. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;113:337–340. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Segawa H, Soares RP, Kawakita M, Beverley SM, Turco SJ. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2028–2035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404915200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dobson DE, Scholtes LD, Myler PJ, Turco SJ, Beverley SM. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2006;146:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dean N, Zhang YB, Poster JB. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31908–31914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goto S, Taniguchi M, Muraoka M, Toyoda H, Sado Y, Kawakita M, Hayashi S. Nature Cell Biology. 2001;3:816–822. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Capasso J, Hirschberg C. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1984;259:4263–4266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ilg T, Etges R, Overath P, McConville MJ, Thomas-Oates J, Thomas J, Homans SW, Ferguson MA. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6834–6840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ng K, EH, AB Biochemical Journal. 1996;317:247–255. doi: 10.1042/bj3170247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ng K, Handman E, Bacic A. Glycobiology. 1994;4:845–853. doi: 10.1093/glycob/4.6.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Segawa H, Kawakita M, Ishida N. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:128–138. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.