Abstract/Summary

Vascular calcification is recognized as a major contributor to cardiovascular disease (CVD) in end stage renal disease (ESRD) patients. Susceptibility to vascular calcification is genetically determined and actively regulated by diverse inducers and inhibitors. One of these inducers, hyperphosphatemia, promotes vascular calcification and is a nontraditional risk factor for CVD mortality in ESRD patients. Vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) respond to elevated phosphate levels by undergoing an osteochondrogenic phenotype change and mineralizing their extracellular matrix through a mechanism requiring sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporters. Disease states and cytokines can increase expression of sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporters in SMCs, thereby increasing susceptibility to calcification even at phosphate concentrations that are in the normal range.

1. Definitions and Clinical Significance of Vascular Calcification

Calcification of the cardiovascular system is associated with a number of diseases including end stage renal disease (ESRD) and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Calcium phosphate deposition, mostly in the form of apatite, is the hallmark of vascular calcification and can occur in the blood vessels, myocardium and cardiac valves. Calcium phosphate deposits are found in distinct layers of the blood vessel and are associated with specific pathologies. Intimal calcification is observed in atherosclerotic lesions [1, 2], whereas medial calcification is common to the arteriosclerosis observed with age and diabetes, and is the major form observed in ESRD [3–5]. In ESRD patients, both intimal and medial calcification occurs, but arterial medial calcification is by far the most prevalent [6, 7]. Levels of calcium on the order of 20 μg/mg were routinely found in the calcified aortas of uremic patients at autopsy [6]. In valves, calcification is a defining feature of aortic valve stenosis, and occurs in both the leaflets and ring, predominantly at sites of inflammation and mechanical stress [8].

Some pathological states of vascular calcification are well recognized for their life threatening potential. For example, calcification is recognized as a major mode of failure of native and bioprosthetic valves [9, 10]. Furthermore, vascular calcification is responsible for calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA), a necrotizing skin condition observed in dialysis patients, associated with extremely high mortality rates [11]. Finally, generalized infantile arterial calcification, a genetic disease characterized by deficiencies in ENPP1, the enzyme that generates the potent inhibitor of calcium phosphate deposition, pyrophosphate, causes arterial calcification, fibrosis, and stenosis leads to premature death in afflicted neonates [12].

In contrast, vascular calcifications associated with age, renal and vascular disease were considered benign for the better part of the last century. However, clinical studies in the past two decades have challenged this dogma. Calcification has been positively correlated with coronary atherosclerotic plaque burden [13, 14] increased risk of myocardial infarction [15–17] and plaque instability [18–20]. Furthermore, in the Rotterdam Coronary Calcification Study, a large population-based study, graded associations between coronary calcification score and stroke were identified [21]. Likewise, coronary calcium score was a strong predictor of incident coronary heart disease in four major racial and ethnic groups in the United States [22]. Similarly, medial arterial calcification is strongly correlated with coronary artery disease and future cardiovascular events including lower extremity amputation in type I diabetics [23, 24] and is a strong prognostic marker of CVD mortality in ESRD patients [25]. These findings may be explained by evidence that arterial medial calcification in large arteries leads to increased stiffness and therefore decreased compliance of these vessels. These mechanical changes are associated with increased arterial pulse wave velocity and pulse pressure, and lead to impaired arterial distensibility, increased afterload favoring left ventricular hypertrophy, and compromised coronary perfusion [26]. Thus, both intimal and medial calcifications may contribute to the morbidity and mortality associated with cardiovascular disease, and are likely to be major contributors to the 10–100 fold increase in cardiovascular mortality risk observed in ESRD patients [27]. Indeed, both the National Kidney Foundation and American Heart Association have indicated that ESRD patients should be considered at the highest risk for cardiovascular disease (NFK K/DOQI clinical guidelines and [28]).

2. Vascular Calcification Is An Actively Regulated, Genetically Determined Process

Growing evidence suggests that vascular calcification, like bone formation, is a highly regulated process, involving both inductive and inhibitory processes ([29] for review). For example, apatite, bone-related noncollagenous proteins (osteocalcin, osteopontin, alkaline phosphatase, Runx2), and matrix vesicles have all been observed in calcified vascular lesions. Furthermore, outright cartilage and bone formation have also been documented [1, 8]. Finally, cells derived from the arterial media, including SMCs, adventitial fibroblasts, and pericytes, undergo osteochondrogenic differentiation and matrix mineralization under the appropriate conditions in vitro [30–34]. These studies suggest that cell-mediated processes tightly control procalcific and anticalcific mediators in the artery so that ectopic calcification is normally avoided. Under pathological conditions, this balance is upset and leads to ectopic mineralization.

Furthermore, susceptibility to vascular calcification appears to be genetically determined in people and in mice. For example, Table 1 lists human genetic syndromes and mouse mutations that include vascular calcification as part of the disorder, indicating that the affected genes normally regulate this process. Furthermore, a small fraction of ESRD patients enter dialysis without vascular calcification and remain calcification-free suggesting genetic protection against this process [35]. More recently, ESRD patients with ENPP1 121KQ genotype (decreased pyrophosphate generating capacity) were found to have significantly higher coronary calcium score and pulse pressure than ENPP1 121KK genotype [36]. Likewise, using inbred and B X H recombinant inbred mouse strains, clear differences in the occurrence of coronary arterial medial calcification in response an atherogenic diet were observed, with the most susceptible strains being DBA/2J and C3H/HeJ, while the least susceptible included C57Bl/6 and MRL/lpr [37]. Interestingly, susceptibility to atherosclerotic plaque formation and cartilaginous metaplasia, especially in ApoE deficient mice, appeared to show the reverse trend, with C57Bl/6 showing much greater lesion formation and ectopic cartilage than C3H mice [37–39]. Furthermore, dystrophic cardiac calcification (DCC), an autosomal recessive complex trait characterized by calcium phosphate deposition in the myocardium following various injurious stimuli, is preferentially induced in the DCC susceptible C3H/HeJ and DBA/2J strains compared to DCC resistant C57Bl/6 strain [40, 41]. Indeed, recent have identified a quantitative trait locus (Dyscalc 1) contributing to the DCC phenotype to encode the ATP binding cassette transporter, ABCC6 [42]. Mutations in this gene in people are responsible for pseudoxanthoma elasticum (Table 1), a condition that includes enhanced vascular calcifications [43]. Of note, the substrate for ABCC6, which is expressed in liver, kidney and heart but not blood vessels, has not yet been identified.

Table 1.

Genes Associated with Vascular Calcification in Mice and Men

| Gene | Mouse Mutant Phenotype* | Human Genetic Mutation/Phenotype |

|---|---|---|

| Matrix Gla Protein | Arterial, valve, and cartilage calcification (Luo, 1997) | Keutel Syndrome/cartilage and soft tissue calcification(Hur, 2005) |

| Fetuin | Low serum HA inhibitory activity; enhanced susceptibility to vitamin D overload-induced vascular calcification (Schafer, 2003) | None reported |

| Osteopontin | Increased calcification of implanted bioprosthetic valve tissue (Steitz, 2002; Ohri, 2005); increased vascular calcification in OPN−/−XMGP−/− mice (Speer, 2002) | None reported |

| Osteoprotegerin | Vascular calcification and osteoporosis (Bucay, 1998) | None reported |

| FGF23 | Hyperphosphatemia; High serum Vitamin D; vascular calcification (Stubbs, 2007) | Familial Tumoral Calcinosis/vascular calcification, hyperphosphatemia, high serum vitamin D (Benet Pages, 2005) |

| Klotho (b-glucuronidase) | Vascular calcification, rapid aging (Kuro-o, 1997) | Tumoral Calcinosis, hyperphosphatemia (Ichikawa, 2007) |

| Nucleotide pyrophosphatase) Enpp1/PC-1/NPP1 | Tip toe walking mouse/vascular and articular cartilage calcification (Okawa, 1998) | Infantile Arterial Calcification/low pyrophosphate, extensive vascular calcification, neonatal lethal(Rutsch, 2003) |

| Ank (pyrophosphate transporter) | Progressive Ankylosis; Articular cartilage calcification; soft tissue calcification (Harmey, 2004) | Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition Disease/chondrocalcinosis; high pyrophosphate (Zaka, 2006) |

| Carbonic Anhydrase II | Small artery VC; osteopetrosis; metabolic acidosis (Spicer, 1989) | Osteopetrosis, metabolic acidosis, brain calcifications (Shah, 2004) |

| Smad 6/Madh6 | Endocardial cushion defects; Valvular calcification(Galvin, 2000) | None reported |

| Desmin | Neonatal cardiomyopathy with calcification (Mavroidis, 2002) | None reported |

| UDP N-acetyl-a-D-galactosamine (GalNT3) | None reported | Familial Tumoral Calcinosis/hyperphosphatemia, vascular calcification, elevated serum vitamin D(Ichikawa, 2005) |

| Fibrillin 1 | Marfan-like syndrome, elastocalcinosis and aneurysm | Marfan Syndrome |

| Fibulin 4 | Valve calcification and stenosis, aortic dilatation | Cutis Laxa, Aortic aneurysm, perinatal lethal (Dasouki, 2007) |

| ABCC6 transporter (substrate unknown) | Extensive soft tissue and vibrissae calcification (Klement, 2005) | Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum/calcification of skin, connective tissue and vasculature (Le Saux, 2000) |

| BMP and Receptor | BMP4 overexpressing transgenic: fibrodysplasia ossificans-like phenotype (Kan, 2004) | ACVR1 BMP receptor, activating mutations:Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva/muscle/soft tissue calcification (Shore, 2006) |

| WRN RecQ helicase | Accelerated mortality in p53 null background (Lombard, 2000) | Werner’s syndrome/soft tissue calcification (Uhrhammer, 2006) |

| Lamin A (LMNA) | Cardiac and skeletal myopathy; progressive loss of vascular SMC and calcification (Varga, 2006) | Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria/calcification associated with atherosclerosis (Eriksson, 2003) |

| Glucocerebrosidase (D409H) | Lysosomal storage disorder, valve calcification not found (Xu, 2003) | Gaucher Disease/lysosomal storage disease; valvular and aortic arch calcification (McMahon, 2001) |

| Transcription Intermediatery Factor 1 (TIF1alpha) | Ectopic calcification including arterioles and medium sized arteries (Ignat, 2008) | None reported |

| Calcium Sensing Receptor(CaSR) | Gprc2aNuf mouse, activating mutation: Ectopic calcification including arterial calcification and cataracts (Hough, 2004) | Activating mutations: Autosomal dominant hypocalcemia,, hypercalciuria, and Bartter-like syndrome (Pollak, 1994) |

loss of function mutation is shown unless otherwise stated

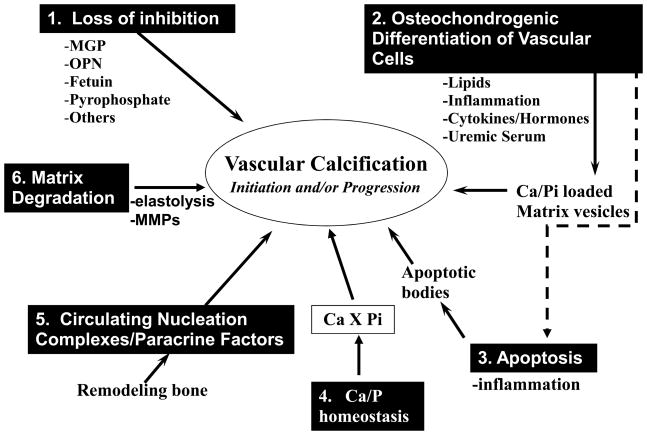

Thus, over the past ten years, our understanding of molecules and processes that regulate ectopic calcification has grown exponentially. As mentioned, much of our understanding comes from identification of genes through linkage or targeted deletion studies that cause human and/or mouse ectopic calcification disorders, respectively. In addition, a number of in vitro and in vivo model systems have been developed that mimic important aspects of ectopic calcification. Figure 1 summarizes the current major theories and regulators of vascular calcification that have been put forward based on these studies including 1) loss of inhibition, 2) induction of osteochondrogenesis, 3) apoptosis, 4) abnormal calcium and phosphate homeostasis, 5) circulating nucleational complexes/paracrine factors derived from bone and 6) matrix degradation. However, the key factors and processes important for any specific disease state are still unknown, and it is likely that a different set of processes/molecules may uniquely be involved in different pathologies. In this regard, serum phosphate and cellular phosphate metabolism are emerging as key regulators of vascular calcification in ESRD.

Fig. 1.

Major Theories of Vascular Calcification

Six different mechanisms that have been proposed to regulate the initiation or progression of vascular calcification are illustrated, along with key molecular mediators where known. The extent to which each of these mechanisms plays a role in vascular calcification in various disease states, including hyperphosphatemia and ESRD, is currently unknown.

3. Hyperphosphatemia, Elevated Phosphate Load, and Vascular Calcification

Evidence for the importance of hyperphosphatemia as a major inducer of vascular calcification comes from studies of genetic syndromes (Table 1) as well as diseases of renal insufficiency. Hyperphosphatemia is observed in two human genetic disorders that cause familial tumoral calcinosis due to mutations in the genes for FGF23, a major phosphaturic hormone, and UDP N-acetyl-α-D-galactosamine [44, 45]. Likewise, in mice, targeted deletion of either FGF23 [46, 47] or klotho, an aging-suppressor gene required for FGF23 function [48], leads to hyperphosphatemia that is accompanied by vascular calcification.

Hyperphosphatemia is also prevalent in patients with ESRD. Evidence from clinical studies reveals that elevated serum phosphate is positively correlated with mortality, and a dramatic increase in risk of death is observed in ESRD patients with a serum phosphate greater than 6.5mg/dL [49]. Importantly, two recent randomized clinical trials showed that lowering serum phosphate levels with a non-calcium containing phosphate binder dramatically slowed progression of vascular calcification in ESRD patients [50, 51]. Moreover, even relatively small elevations in serum phosphate in the high normal range (3.5–4.5 mg/dL) have been correlated with increased risk of cardiovascular and all cause mortality in both chronic kidney disease patients [52] and the general population [53]. Thus phosphate load, even in the absence of outright hyperphosphatemia, may be an important driver of vascular calcification.

Experimental models of renal insufficiency also point to a role of elevated phosphate in vascular calcification. Uremic rats show aortic medial calcification with prolonged (6 months) feeding of a high phosphate diet that could be blocked by treatment with the phosphate binder, sevelamer, [54]. Hyperphosphatemia has also been correlated with atherosclerotic calcification in uremic, high fat fed LDLR null mice [55], and sevelamer decreased vascular calcification in this setting. Likewise, Massy et al [56] showed that uremia accelerated atherosclerosis and vascular calcification in ApoE−/− mice and sevelamer-prevented uremia enhanced atherosclerotic lesion size as well as calcification in this model. Finally, hyperphosphatemia was correlated with extensive arterial medial calcification similar in type and extent to that observed in ESRD patients in the calcification-prone DBA/2 mouse in response to severe renal insufficiency and high phosphate feeding (Giachelli et al, unpublished observations).

4. Potential Role of the Sodium-Dependent Phosphate Cotransporter, Pit-1, in Vascular Calcification

Consistent with clinical and animal studies, phosphate levels comparable to those seen in hyperphosphatemic individuals [49] induce SMC calcification and osteochondrogenic phenotype change in vitro [57–59]. No calcification occurs in human SMCs cultured in medium containing 1.4 mM phosphate, but calcification is induced in a dose- and time-dependent when phosphate levels are increased from 1.6 mM to 3.0 mM. The finding that elevated phosphate induces SMC calcification was confirmed by other investigators [58, 60]. In addition to SMC cultures, rat aortas cultured in elevated phosphate medium undergo medial calcification [61]. Together, these studies demonstrate that elevated phosphate is a strong inducer of vascular calcification.

Phosphate transport into cells is primarily mediated by sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporters, and three types of cotransporters have been identified based on structure, tissues expression and biochemical characteristics [62, 63]. The type I and type II sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporters are primarily expressed in kidney and intestinal epithelium, and their functions are important for the maintenance of phosphate homeostasis in body [62, 63]. The type III sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporters, Pit-1 and Pit-2, were originally identified as cell surface receptors for the gibbon ape leukemia virus (Glvr-1) and the amphotropic murine retrovirus (Ram-1), respectively. Type III members are widely in tissues such as kidney, liver, lung, heart, brain, osteoblast, chondrocyte and SMCs [57, 64–69].

A functional sodium-dependent phosphate transport system has been characterized in vascular SMCs [57, 69, 70]. RT-PCR revealed expression of type III sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporters, Pit-1 and Pit-2, in vascular SMCs, while no transcripts for type I and type II sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporters were detected. Real-time PCR indicated that Pit-1 mRNA levels were higher than Pit-2 expressed in SMC [69]. Treatment of vascular SMCs with a competitive inhibitor of sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporters, phosphonoformic acid (PFA), caused a dose-dependent inhibition of phosphate uptake, calcification, and osteochondrogenic phenotype in SMCs [57, 58, 60]. These results suggest that phosphate transporter activity is necessary for mineralization as well as osteochondrogenic transition in human SMCs.

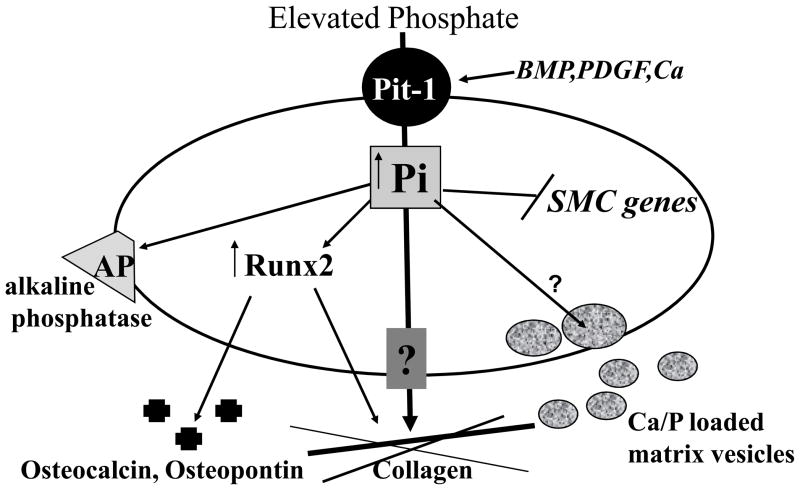

Since PFA has lower affinity for type III than type II receptors [70], the requirement of phosphate uptake for SMC calcification was further examined using SMCs that were stably transduced with Pit-1 specific small hairpin RNA (shRNA) [69]. Pit-1 shRNA expressing cells had reduced mRNA and protein levels of Pit-1 as detected by Northern and Western blots, respectively. Sodium-dependent phosphate uptake in the cells was reduced compared to that in control cells. After incubation with elevated phosphate for 7, 10 or 14 days, there was substantially reduced calcification in Pit-1 knockdown cells compared to control cells. Of interest, restoration of phosphate uptake in Pit-1 knockdown cells by over-expression of mouse Pit-1 rescued elevated phosphate-induced mineralization. Similar to PFA, inhibition of phosphate uptake by Pit-1 shRNA blocked the expression of phosphate-induced osteogenic differentiation markers, Runx2 and osteopontin. Furthermore, we determined that neither phosphate loading of matrix vesicles nor cell death was mediated by Pit-1 in SMC. These studies indicated that sodium dependent phosphate cotransporters, in particular Pit-1, might be a major mechanism for controlling vascular calcification and SMC phenotypic state. Taken together, these results demonstrate that phosphate transport via Pit-1 is required for calcification in cultured SMC. A model for the possible functions of elevated phosphate and Pit-1 in SMC calcification is shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Proposed Role of Elevated Phosphate (Pi) in Osteochondrogenic Phenotype Change and Matrix Mineralization in Vascular SMC. Pi enters the cell through the sodium dependent phosphate cotransporters, Pit-1, and induces an osteochondrogenic phenotype change. This stimulates matrix vesicle calcium and Pi loading, as well as matrix changes that promote calcification. Molecules involved in regulating Pi loading of matrix vesicles or Pi efflux are currently unknown.

Recent studies have supported a role for increased phosphate uptake via Pit-1 in vascular calcification in vivo. Mizobuchi et al showed that mRNA levels of Pit-1 and Runx2 were increased in calcified aorta of uremic rats with severe hyperparathyroidism, while no increase was observed in non-calcified aorta of control animals [71]. Likewise, LDLR−/− mice fed a high-fat diet showed elevated levels of serum tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and Pit-1 in calcified aortic calcification. In vitro, several factors that have been shown to induce vascular calcification also induce Pit-1 in SMCs. Long-term treatment of human SMCs with elevated calcium levels leads to increased Pit-1 mRNA levels, phosphate uptake and calcification [72]. Likewise, PDGF promotes calcification in cultured SMCs and strongly induces Pit-1 expression [73]. In addition, bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2), a potent osteogenic protein, has been shown to promote vascular calcification [34, 74, 75] and BMP-2 increased phosphate uptake in a time-and dose-dependent manner [76]. Interestingly, BMP-2 also promoted mineralization and upregulated Pit-1 expression in osteoblasts, and BMP2-enhanced mineralization in these cells was abrogated by Pit-1 siRNA [77]. Finally, transglutaminase (TG) appears to be an important regulator of endogenous expression, since Pit1 levels were observed in TG+/+ SMCs but absent in TG−/− SMCs in the presence or absence of elevated phosphate [78]. Thus, it is likely that phosphate transport via Pit-1 is a common requirement for cell-mediated biomineralization.

5. Conclusions

Vascular calcification is a major contributor to CVD in ESRD patients. Susceptibility to vascular calcification is genetically determined and involves a growing number of inducers and inhibitors. Hyperphosphatemia promotes vascular calcification in part by promoting SMCs to undergo an osteochondrogenic phenotype change through a mechanism requiring sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporters. Upregulation of sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporters in SMCs by disease state and cytokines may facilitate vascular calcification even when serum phosphate levels are in the normal range.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Giachelli thanks all lab members who contributed to the studies reviewed in this article. Dr. Giachelli is currently supported by NIH grants HL18645, HL081785, and HL62329, and a sponsored research agreement from Abbott.

References

- 1.Hunt JL, Fairman R, Mitchell ME, et al. Bone formation in carotid plaques: a clinicopathological study. Stroke. 2002;33:1214–1219. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000013741.41309.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke AP, Taylor A, Farb A, et al. Coronary calcification: insights from sudden coronary death victims. Z Kardiol. 2000;89 (Suppl 2):49–53. doi: 10.1007/s003920070099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monckeberg JG. Uber die reine mediaverkalkung der extremitaten-arteries und ihr Verhalten zur arteriosklerose. Virchows Arch. 1903;171:141–167. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edmonds ME, Morrison N, Laws JW, et al. Medial arterial calcification and diabetic neuropathy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;284:928–930. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6320.928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Micheletti RG, Fishbein GA, Currier JS, et al. Monckeberg sclerosis revisited: a clarification of the histologic definition of Monckeberg sclerosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:43–47. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-43-MSRACO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibels LS, Alfrey AC, Huffer WE, et al. Arterial calcification and pathology in uremic patients undergoing dialysis. Am J Med. 1979;66:790–796. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)91118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwarz U, Buzello M, Ritz E, et al. Morphology of coronary atherosclerotic lesions in patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:218–223. doi: 10.1093/ndt/15.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohler ER, 3rd, Gannon F, Reynolds C, et al. Bone formation and inflammation in cardiac valves. Circulation. 2001;103:1522–1528. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.11.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoen FJ, Levy RJ. Founder’s Award, 25th Annual Meeting of the Society for Biomaterials, perspectives. Providence, RI, April 28-May 2, 1999. Tissue heart valves: current challenges and future research perspectives. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;47:439–465. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19991215)47:4<439::aid-jbm1>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Keefe JH, Lavie CJ, Nishimura RA, et al. Degenerative aortic stenosis. One effect of the graying of America. Postgraduate Medicine. 1991;89:143–154. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1991.11700822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coates T, Kirkland GS, Dymock RB, et al. Cutaneous necrosis from calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:384–391. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9740153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutsch F, Ruf N, Vaingankar S, et al. Mutations in ENPP1 are associated with ‘idiopathic’ infantile arterial calcification. Nat Genet. 2003;34:379–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rumberger JA, Simons DB, Fitzpatrick LA, et al. Coronary artery calcium area by electron-beam computed tomography and coronary atherosclerotic plaque area. A histopathologic correlative study. Circulation. 1995;92:2157–2162. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.8.2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sangiorgi G, Rumberger JA, Severson A, et al. Arterial calcification and not lumen stenosis is highly correlated with atherosclerotic plaque burden in humans: a histologic study of 723 coronary artery segments using nondecalcifying methodology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:126–133. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beadenkopf WG, Daoud AS, Love BM. Calcification in the coronary arteries and its relationship to arteriosclerosis and myocardial infarction. Am J Roentgenol. 1964;92:865–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Locker TH, Schwartz RS, Cotta CW, et al. Fluoroscopic coronary artery calcification and asociated coronary disease in asymptomatic young men. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:1167–1172. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90319-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puentes G, Detrano R, Tang W, et al. Estimation of coronary calcium mass using electron beam computed tomography: a promising approach for predicting coronary events? Circulation. 1995;92:I313. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzgerald PJ, Ports TA, Yock PG. Contribution of localized calcium deposits to dissection after angioplasty: an observational study using intravascular ultrasound. Circulation. 1992;86:64–70. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehara S, Kobayashi Y, Yoshiyama M, et al. Spotty calcification typifies the culprit plaque in patients with acute myocardial infarction: an intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2004;110:3424–3429. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148131.41425.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li ZY, Howarth S, Tang T, et al. Does calcium deposition play a role in the stability of atheroma? Location may be the key. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;24:452–459. doi: 10.1159/000108436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollander M, Hak AE, Koudstaal PJ, et al. Comparison between measures of atherosclerosis and risk of stroke: the Rotterdam Study. Stroke. 2003;34:2367–2372. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000091393.32060.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1336–1345. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olson JC, Edmundowicz D, Becker DJ, et al. Coronary calcium in adults with type 1 diabetes: a stronger correlate of clinical coronary artery disease in men than in women. Diabetes. 2000;49:1571–1578. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.9.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehto S, Niskanen L, Suhonen L, et al. Medial artery calcification. A neglected harbinger of cardiovascular complications in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:978–983. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.8.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.London GM, Guerin AP, Marchais SJ, et al. Arterial media calcification in end-stage renal disease: impact on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:1731–1740. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guerin AP, Blacher J, Pannier B, et al. Impact of aortic stiffness attenuation on survival of patients in end-stage renal failure. Circulation. 2001;103:987–992. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.7.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foley RN, Parfrey PS. Cardiovascular disease and mortality in ESRD. J Nephrol. 1998;11:239–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, et al. Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Hypertension. 2003;42:1050–1065. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000102971.85504.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Abbadi M, Giachelli CM. Mechanisms of vascular calcification. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007;14:54–66. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wada T, McKee MD, Stietz S, et al. Calcification of vascular smooth muscle cell cultures: inhibition by osteopontin. Circ Res. 1999;84:1–6. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jono S, Peinado C, Giachelli CM. Phosphorylation of osteopontin is required for inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20197–20203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909174199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tintut Y, Alfonso Z, Saini T, et al. Multilineage potential of cells from the artery wall. Circulation. 2003;108:2505–2510. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000096485.64373.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doherty MJ, Ashton BA, Walsh S, et al. Vascular pericytes express osteogenic potential in vitro and in vivo. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.5.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng SL, Shao JS, Charlton-Kachigian N, et al. MSX2 promotes osteogenesis and suppresses adipogenic differentiation of multipotent mesenchymal progenitors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45969–45977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306972200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sigrist MK, Taal MW, Bungay P, et al. Progressive vascular calcification over 2 years is associated with arterial stiffening and increased mortality in patients with stages 4 and 5 chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:1241–1248. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02190507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eller P, Hochegger K, Feuchtner GM, et al. Impact of ENPP1 genotype on arterial calcification in patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:321–327. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qiao JH, Xie PZ, Fishbein MC, et al. Pathology of atheromatous lesions in inbred and genetically engineered mice. Genetic determination of arterial calcification. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:1480–1497. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.9.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qiao JH, Fishbein MC, Demer LL, et al. Genetic determination of cartilaginous metaplasia in mouse aorta. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:2265–2272. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.12.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang SS, Shi W, Wang X, et al. Mapping, genetic isolation, and characterization of genetic loci that determine resistance to atherosclerosis in C3H mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2671–2676. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.148106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Korff S, Riechert N, Schoensiegel F, et al. Calcification of myocardial necrosis is common in mice. Virchows Arch. 2006;448:630–638. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-0071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van den Broek FA, Bakker R, den Bieman M, et al. Genetic analysis of dystrophic cardiac calcification in DBA/2 mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;253:204–208. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meng H, Vera I, Che N, et al. Identification of Abcc6 as the major causal gene for dystrophic cardiac calcification in mice through integrative genomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4530–4535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607620104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Le Saux O, Urban Z, Tschuch C, et al. Mutations in a gene encoding an ABC transporter cause pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Nat Genet. 2000;25:223–227. doi: 10.1038/76102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benet-Pages A, Orlik P, Strom TM, et al. An FGF23 missense mutation causes familial tumoral calcinosis with hyperphosphatemia. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:385–390. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ichikawa S, Lyles KW, Econs MJ. A novel GALNT3 mutation in a pseudoautosomal dominant form of tumoral calcinosis: evidence that the disorder is autosomal recessive. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2420–2423. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stubbs J, Liu S, Quarles LD. Role of fibroblast growth factor 23 in phosphate homeostasis and pathogenesis of disordered mineral metabolism in chronic kidney disease. Semin Dial. 2007;20:302–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stubbs JR, Liu S, Tang W, et al. Role of hyperphosphatemia and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in vascular calcification and mortality in fibroblastic growth factor 23 null mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2116–2124. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuroo M, Matsamura Y, Aizawa H, et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390:45–51. doi: 10.1038/36285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Block GA. Prevalence and clinical consequences of elevated Ca × P product in hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 2000;54:318–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chertow GM, Burke SK, Raggi P. Sevelamer attenuates the progression of coronary and aortic calcification in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2002;62:245–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Russo D, Miranda I, Ruocco C, et al. The progression of coronary artery calcification in predialysis patients on calcium carbonate or sevelamer. Kidney Int. 2007;72:1255–1261. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kestenbaum B, Sampson JN, Rudser KD, et al. Serum phosphate levels and mortality risk among people with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:520–528. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tonelli M, Sacks F, Pfeffer M, et al. Relation between serum phosphate level and cardiovascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation. 2005;112:2627–2633. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.553198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cozzolino M, Dusso AS, Liapis H, et al. The effects of sevelamer hydrochloride and calcium carbonate on kidney calcification in uremic rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2299–2308. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000025782.24383.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davies MR, Lund RJ, Hruska KA. BMP-7 Is an Efficacious Treatment of Vascular Calcification in a Murine Model of Atherosclerosis and Chronic Renal Failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1559–1567. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000068404.57780.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Massy ZA, Ivanovski O, Nguyen-Khoa T, et al. Uremia accelerates both atherosclerosis and arterial calcification in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:109–116. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004060495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jono S, McKee MD, Murry CE, et al. Phosphate regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. Circ Res. 2000;87:E10–17. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.7.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sugitani H, Wachi H, Murata H, et al. Characterization of an in vitro model of calcification in retinal pigmented epithelial cells. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2003;10:48–56. doi: 10.5551/jat.10.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steitz SA, Speer MY, Curinga G, et al. Smooth muscle cell phenotypic transition associated with calcification: upregulation of Cbfa1 and downregulation of smooth muscle lineage markers. Circ Res. 2001;89:1147–1154. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.101070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen NX, O’Neill KD, Duan D, et al. Phosphorus and uremic serum up-regulate osteopontin expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Kidney International. 2002;62:1724–1731. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lomashvili K, Garg P, O’Neill WC. Chemical and hormonal determinants of vascular calcification in vitro. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1464–1470. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takeda E, Taketani Y, Morita K, et al. Sodium-dependent phosphate co-transporters. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;31:377–381. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Werner A, Dehmelt L, Nalbant P. Na+-dependent phosphate cotransporters: the NaPi protein families. J Exp Biol. 1998;201:3135–3142. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.23.3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boyer CJ, Baines AD, Beaulieu E, et al. Immunodetection of a type III sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporter in tissues and OK cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1368:73–83. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(97)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kakita A, Suzuki A, Nishiwaki K, et al. Stimulation of Na-dependent phosphate transport by platelet-derived growth factor in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis. 2004;174:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Palmer G, Manen D, Bonjour J, et al. Structure of the murine Pit1 phosphate transporter/retrovirus receptor gene and functional characterization of its promoter region. Gene. 2000;244:35–45. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Palmer G, Bonjour JP, Caverzasio J. Expression of a newly identified phosphate transporter/retrovirus receptor in human SaOS-2 osteoblast-like cells and its regulation by insulin-like growth factor I. Endocrinology. 1997;138:5202–5209. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.12.5561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kavanaugh MP, Miller DG, Zhang W, et al. Cell-surface receptors for gibbon ape leukemia virus and amphotropic murine retrovirus are inducible sodium-dependent phosphate symporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:7071–7075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li X, Yang HY, Giachelli CM. Role of the sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporter, Pit-1, in vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. Circ Res. 2006;98:905–912. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000216409.20863.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Villa-Bellosta R, Bogaert YE, Levi M, et al. Characterization of phosphate transport in rat vascular smooth muscle cells: implications for vascular calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1030–1036. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.106.132266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mizobuchi M, Finch JL, Martin DR, et al. Differential effects of vitamin D receptor activators on vascular calcification in uremic rats. Kidney Int. 2007;72:709–715. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang H, Curinga G, Giachelli CM. Elevated extracellular calcium levels induce smooth muscle cell matrix mineralization in vitro. Kidney Int. 2004;66:2293–2299. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.66015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Giachelli CM. Vascular calcification: in vitro evidence for the role of inorganic phosphate. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:S300–304. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000081663.52165.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zebboudj AF, Shin V, Bostrom K. Matrix GLA protein and BMP-2 regulate osteoinduction in calcifying vascular cells. J Cell Biochem. 2003;90:756–765. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen NX, Duan D, O’Neill KD, et al. High glucose increases the expression of Cbfa1 and BMP-2 and enhances the calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:3435–3442. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li X, Yang HY, Giachelli CM. BMP-2 promotes phosphate uptake, phenotypic modulation, and calcification of human vascular smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Suzuki A, Ghayor C, Guicheux J, et al. Enhanced expression of the inorganic phosphate transporter Pit-1 is involved in BMP-2-induced matrix mineralization in osteoblast-like cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:674–683. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.020603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Johnson KA, Polewski M, Terkeltaub RA. Transglutaminase 2 is central to induction of the arterial calcification program by smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2008;102:529–537. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.154260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]