Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

The present exploratory, descriptive study aimed to determine the designated time for mandatory pain content in curricula of major Canadian universities for students in health science and veterinary programs before being licensed.

METHOD:

Major Canadian university sites (n=10) were chosen where health science faculties included at least medicine (n=10) and nursing (n=10); many also included dentistry (n=8), pharmacy (n=7), physical therapy (n=8) and/or occupational therapy (n=6). These disciplines provide the largest number of students entering the workforce but are not the only ones contributing to the health professional team. Veterinary programs (n=4) were also surveyed as a comparison. The Pain Education Survey, developed from previous research and piloted, was used to determine total mandatory pain hours.

RESULTS:

The majority of health science programs (67.5%) were unable to specify designated hours for pain. Only 32.5% respondents could identify specific hours allotted for pain course content and/or additional clinical conferences. The average total time per discipline across all years varied from 13 h to 41 h (range 0 h to 109 h). All veterinary respondents identified mandatory designated pain content time (mean 87 h, range 27 h to 200 h). The proportion allotted to the eight content categories varied, but time was least for pain misbeliefs, assessment and monitoring/follow-up planning.

CONCLUSIONS:

Only one-third of the present sample could identify time designated for teaching mandatory pain content. Two-thirds reported ‘integrated’ content that was not quantifiable or able to be determined, which may suggest it is not a priority at that site. Many expressed a need for pain-related curriculum resources.

Keywords: Canadian health science universities, Prelicensure pain curricula

Abstract

OBJECTIF :

La présente étude exploratoire descriptive visait à déterminer la période désignée pour enseigner la douleur dans le programme des grandes universités canadiennes aux étudiants en sciences de la santé et en sciences vétérinaires avant l’obtention du permis d’exercer.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

On a retenu les grands établissements universitaires canadiens (n=10) dont les facultés de science de la santé incluaient au moins la médecine (n=10) et les soins infirmiers (n=10). La plupart incluaient aussi la dentisterie (n=8), la pharmacie (n=7), la physiothérapie (n=8) ou l’ergothérapie (n=6). Ces disciplines fournissent le plus grand nombre d’étudiants qui intègrent le milieu du travail, mais ne sont pas les seules à contribuer à l’équipe de professionnels de la santé. Les programmes vétérinaires (n=4) ont également été sondés à titre comparatif. Le sondage sur l’enseignement de la douleur, élaboré à partir de recherches antérieures et mis en œuvre dans des projets pilotes, a permis de déterminer le total d’heures obligatoires consacrées à la douleur.

RÉSULTATS :

La majorité des programmes de sciences de la santé (67,5 %) étaient incapables de préciser les heures désignées pour l’enseignement de la douleur. Seulement 32,5 % des répondants pouvaient préciser les heures attribuées à la douleur dans les cours ou dans les conférences cliniques supplémentaires. La période totale moyenne par discipline dans l’ensemble des années variait entre 13 heures et 41 heures (plage de 0 heure à 109 heures). Tous les répondants des écoles vétérinaires ont fait état d’heures d’enseignement consacrées à la douleur (moyenne de 87 heures, plage de 27 heures à 200 heures). La proportion attribuée aux huit catégories de contenu était variable, mais la période était moindre pour les méconceptions, l’évaluation et la planification du suivi de la douleur.

CONCLUSIONS :

Seulement le tiers du présent échantillon pouvait préciser une période attribuée à l’enseignement obligatoire de la douleur dans les programmes. Les deux tiers du contenu « intégré » déclaré n’étaient pas quantifiables ou étaient impossibles à déterminer, ce qui peut laisser croire que ce n’est pas une priorité dans ces établissements. Nombreux sont ceux qui ont exprimé la nécessité de ressources pour un programme sur la douleur.

Unrelieved pain is a widespread global problem for divergent patient groups across the lifespan. Pain education for health professionals at all levels has been repeatedly identified as an important step toward more effective pain management practices (1). However, evidence indicates that health professionals lack sufficient knowledge and skill to adequately assess and manage pain (2,3).

Despite evidence that well-designed pain curricula can significantly improve pain knowledge and beliefs of health professional students (3–6), reports of pain content in prelicensure (prequalifying, preregistration) curricula are minimal.

Students have lacked important pain knowledge at graduation (1,7–10), and attitudes and beliefs reinforced as undergraduates are more difficult to change later (11). More recently, prelicensure interprofessional education has been recognized as a critical step in ensuring that graduates entering practice will be competent in patient-centred collaboration (12–15), including in pain management (16). Moreover, Barr et al’s (17) systematic review reported that the most common goals of prelicensure interprofessional education were to reduce the development of prejudices and negative stereotypes and to lay the foundation for future interprofessional learning and practice. However, outside of the University of Toronto Centre for the Study of Pain Interfaculty Pain Curriculum (Toronto, Ontario), an integrated pain curriculum for prelicensure students from six health science faculties and departments (2,3), the degree to which pain content is included in Canadian university health science curricula is not known.

The purpose of the present exploratory, descriptive study was to survey the designated time for mandatory pain content being taught in curricula of major Canadian universities for students in health science and veterinary programs before being licensed. While there are veterinary programs within some health science faculties, for clarity in the present paper, health science programs will refer to human, and not animal care. These data are being used by the Canadian Pain Society to raise national awareness of unrelieved pain and the need for national pain curricula that includes an interprofessional focus, as well as to encourage the Canadian federal government to support greater funding for pain education and research.

METHODS

For the purposes of the present exploratory study, universitybased sites that included prelicensure programs for medicine and nursing were surveyed. At universities that also included dentistry, pharmacy, physical therapy and/or occupational therapy, these programs were also included. These faculties and departments were included because they currently have the largest number of students entering the workforce. Therefore, the present survey was not meant to be comprehensive; other health professional groups also make vital contributions to the pain management effort. For comparison with the health science faculties, veterinary colleges were also included.

Coinvestigators at each university site hired a research assistant to collect data from their health science faculty, department or school(s) using the Pain Education Survey (PES). The PES was adapted from previous research (18,19) and includes eight items also used in the measure to evaluate the University of Toronto Centre for the Study of Pain Interfaculty Pain Curriculum. Face validity and generalizability were established by a focus group of 10 interprofessional pain education experts; it was also pilot tested with faculty at one site before administration.

At each site, the coinvestigators helped the research assistant identify the appropriate faculty member in each of the selected health science programs to approach to complete the survey, such as those responsible for program curricula with knowledge of course-related pain content. Faculty members were given an explanatory letter about the study insuring confidentiality of site-specific data, and their informed consent was implied by completion of the survey. Although the survey did not involve the collection of data pertaining to patients or students, ethical approval was sought and received from the University of Toronto, and by individual sites as required.

Data entry and analysis were completed by an experienced research associate and PhD candidate at the University of Toronto, supervised by the principal investigators. Descriptive and summary statistics were used for data analysis to determine the average number of hours dedicated to mandatory formal teaching on pain at each site, as well as the proportion of total hours dedicated to teaching various pain-related content areas. The latter included pain neurophysiology and mechanisms, etiology and prevalence, pain-related misbeliefs and barriers to effective pain management, pain assessment and measurement, analgesics and management of adverse effects, nonpharmacological pain management strategies, the multidimensional nature of the pain experience and related implications for effective pain management, and monitoring, quality and pain policy and guidelines. When the time dedicated to teaching formal pain content was not specified (and these data could not be obtained), a score of 0 was assigned. It was deemed inappropriate to impute the mean number of formal hours (as opposed to scores of zero) where these data were missing because there are no previous reliable data indicating the average number of hours dedicated to formal pain teaching in Canadian universities, the reliability of the PES is yet to be established, and if the 67.5% of responses given as 0 were excluded, calculated means would have been based on only 32.5% of responses.

All data were housed in locked storage at the Lawrence S Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing, University of Toronto. The list of respondent names and contact information were stored separately from these data.

RESULTS

Participants

Ten sites of major universities from seven of the eight provinces across Canada with a medical school were included. Response rates were excellent from most disciplines and included a total of 42 respondents across faculties and departments (Table 1). The length of health science programs varied from two to five years, including dentistry (four years), medicine (three to five years), nursing (two to four years), pharmacy (four to five years), physical therapy (two years) and occupational therapy (two to three years). Veterinary programs were each four years long.

TABLE 1.

Survey responses by faculty or department

| Faculty or department | Site responses, n | Total sites, n | Response rate, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dentistry | 5 | 8 | 63 |

| Medicine | 9 | 10 | 90 |

| Nursing | 9 | 10 | 90 |

| Occupational therapy | 3 | 6 | 50 |

| Pharmacy | 5 | 7 | 71 |

| Physical therapy | 7 | 8 | 88 |

| Veterinary | 4 | 4 | 100 |

Total designated pain content hours for health science and veterinary curricula

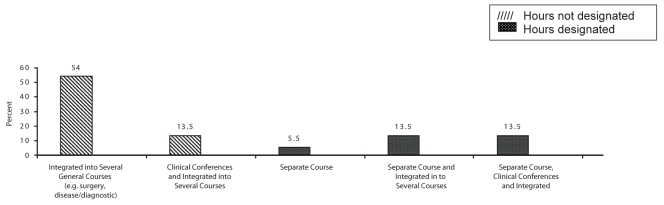

Over 90% of the health science programs and all veterinary programs stated they included mandatory formal pain content in the curriculum. However, the understanding of ‘formal’ by respondents varied, as reflected in their account of specific presentation methods. The majority (67.5%) of health science programs were unable to specify designated hours for pain because they had ‘integrated content’ across several courses and/or clinical conferences (Figure 1). Designated mandatory formal pain content was reported for only 32.5% as a separate course or content plus for some also as being integrated into several other courses and/or clinical conferences (Figure 1). Of these, 16% reported that content was both mandatory and elective, suggesting that there was additional content available for those who were interested in learning more about pain. All veterinary respondents were able to identify mandatory designated formal pain content hours. Although health science program responses indicated that some pain content was taught yearly, for many it was taught in the second year. Pain content in the veterinary programs was reported as being taught yearly with a concentration in the second, third and final years.

Figure 1).

Presentation methods for mandatory designated pain content

Those stating they had no formal pain content continued to complete the survey, indicating that pain education may be addressed through informal methods. Most respondents indicated they had faculty members with expertise to teach pain content.

Pain content taught in an interdisciplinary context was variable. Thirty-four per cent of respondents reported that some pain content or class was shared among disciplines, although only approximately one-half of these (55%) identified a specific number of hours. Excluding one site with a 20 h interfaculty curriculum, the mean shared time was 10 h (range 0.5 h to 20 h). Dentistry frequently reported shared courses, mostly with medicine. Veterinary programs did not share their pain curricula with other disciplines.

Total designated pain content hours by discipline

The average total time designated for formal pain teaching within each discipline is outlined in Table 2. The 20 h for the standardized interfaculty curriculum for six health science programs at one site were excluded to give a more accurate picture of the pain content being taught across Canada. Sites unable to identify mandatory pain content included one each of dentistry, medicine and occupational therapy sites, and two nursing sites.

TABLE 2.

Average total hours for designated mandatory formal content by discipline*

| Faculty or department | Site responses, n | Total hours, mean ± SD | Range | Mean student, n* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dentistry | 5 | 15±10 | 0–24 | 47 |

| Medicine | 9 | 16±11 | 0–38 | 133 |

| Nursing | 9 | 31±42 | 0–109 | 133 |

| Occupational therapy | 3 | 28±25 | 0–48 | 47 |

| Pharmacy | 5 | 13±13 | 2–33 | 123 |

| Physical therapy | 7 | 41±16 | 18–69 | 55 |

| Veterinary medicine | 4 | 87±98 | 27–200 | 66 |

Outlier of 20 h at the University of Toronto Centre for the Study of Pain Interfaculty Pain Curriculum was excluded; only additional hours for this site were included

Although 16 respondents indicated that pain education was also addressed in clinical placements, most were unable to estimate the duration and indicated that it was variable depending on the particular clinical placement. Three respondents reported offering an elective for small groups of students to have experience in a pain clinic or other setting where pain is a major focus. Six additional programs reported offering electives for small groups of students with specialized pain content and clinical practice (eg, palliative care).

Percentage of designated hours for content category by discipline

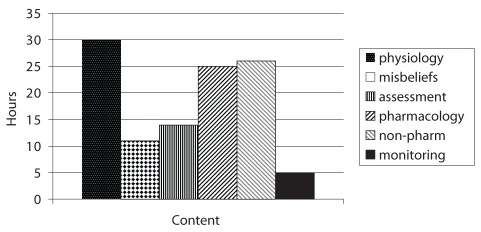

Respondents were asked to categorize the pain content covered in their curriculum into eight specific areas and estimate the time spent teaching each category. As outlined in Table 3, the health science programs addressed all eight pain content areas in varying degrees of frequency. The percentages represent the proportion of the total teaching time (Table 2) allotted to each content category. Within the allotted hours, the proportion focused on each content category varied by discipline. For example, percentages for neurophysiology and pharmacological pain management were highest for medicine and pharmacy, and those for nonpharmacological management were highest for occupational therapy and physical therapy. The least number of hours were allotted for pain misbeliefs, assessment and monitoring/follow-up planning across all health science programs (Figure 2). For the veterinary programs, pain content areas focused on physiology, assessment and pharmacology (analgesia) across all years.

TABLE 3.

Designated mandatory formal hours for content categories by discipline*

| Dentistry | Medicine | Nursing | Occupational therapy | Pharmacy | Physical therapy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurophysiology/mechanisms | 13 | 30 | 19 | 10 | 26 | 14 |

| Etiology/prevalence | 12 | 13 | 7 | 0 | 9 | 8 |

| Misbeliefs/barriers, challenges | 6 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 11 |

| Assessment/measurement | 6 | 7 | 13 | 14 | 13 | 11 |

| Management: Analgesics/adverse effects | 14 | 25 | 12 | 0 | 21 | 10 |

| Management: Nonpharmacological | 17 | 5 | 8 | 26 | 5 | 34 |

| Multidimensional nature of pain and management implications | 9 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 16 | 11 |

| Monitoring, QI policy/guidelines | 2 | 0.5 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 1 |

Data presented as percentages. Numbers are rounded to nearest percentage and totals may not sum to 100%.

Outlier of 20 h at the University of Toronto Centre for the Study of Pain Interfaculty Pain Curriculum was excluded. QI Quality improvement

Figure 2).

Number of designated mandatory hours allotted to pain content categories. Non-pharm Nonpharmacological

Participant comments about pain curriculum challenges

The final section of the PES allowed for comments and three themes in particular emerged from descriptive analysis: difficulty in quantifying hours, particularly in clinical placements; difficulty in identifying hours for specific content; and lack of interdisciplinary education. Most health science respondents stated that students’ exposure to the care of patients in pain depended on what happened during the students’ clinical placements. As a result, pain education varied among students depending on their particular clinical experiences and clinicians involved. Therefore, most respondents were unable to estimate the amount of time spent on pain during clinical placements. Divergent concerns were expressed – some respondents stated that the amount of pain education students received would be underestimated because the clinical component of pain education was not able to be captured; others stated that they did not have control over learning in clinical placements. In comparison, veterinary respondents described specific allotted time and content for discussion of the pain management for each patient in clinical rotations.

Many respondents struggled with further quantifying the amount of time spent on formal content in each of the eight categories. Several suggested that their content areas were too integrated to try break them down as the survey suggested. It is noteworthy that several respondents indicated that pain was mentioned in many different courses, but only as a diagnostic indicator of etiology related to the presentation of illnesses and the need for investigation.

Some respondents reported ongoing initiatives that offered interprofessional pain education opportunities including a 2 h module, a course elective for student groups or a 20 h interfaculty curriculum for six health science faculties. Most, however, did not currently combine their pain content with other professions. Several stated that having a shared pain content curriculum would be beneficial, along with a clearer delineation of role-related responsibilities for pain management.

Participant suggestions for educational resources

The majority of respondents reported that they would use pain curriculum resources if available and provided several suggestions. In particular, case studies or modules were identified by respondents from a variety of disciplines (n=25) as a helpful strategy to integrate students’ theoretical knowledge into clinical situations, particularly if they reflected a range of clinical complexity. Other needs identified included resources to reflect an interdisciplinary or interprofessional approach to pain assessment and management, and Web-based resources or other multimedia resources, such as PowerPoint presentations, videos and pictures. Resources addressing particular content areas were also mentioned, specifically those addressing dental pain, persistent pain and neuroanatomy or neurophysiology. Resources to assist educators in keeping up to date with research and evidence-informed practice were also mentioned.

DISCUSSION

Despite the availability of internationally accepted core and discipline-specific curricula (20), the majority of health science faculties and departments (67.5%) found it difficult and were unable to delineate the actual hours allotted to teaching pain content in their curriculum, including clinical placements. The clinical placement hours depend on the site supervision. Although respondents stated that pain content was integrated across courses, it is problematic that they were unable to quantify specific mandatory hours overall and for specific content categories. It is of concern that only one-third (32.5%) of respondents were able to identify designated pain content hours – some with a considerable number of hours. Moreover, actual teaching hours allotted for some categories were minimal; for example, pain assessment – so critical to successful management – in some instances had fewer hours than other categories, except monitoring, which was minimal across all disciplines. Two models that stood out as advancing pain curricula were a clinical practice model for medicine that involved a pain clinic or pain-focused practice area at one site, and a 20 h interprofessional pain curriculum for six health science faculties and departments, with specific competencies and objectives at another.

Pain content categories for the veterinary respondents were mainly physiology, assessment and management. On average, they reported considerably more hours designated for mandatory formal pain teaching, including in clinical placements, than those indicated in the human health science curricula.

Although the need for interprofessional pain education was expressed, this was not yet in place for most respondents. As well, the need for clarification of roles was identified by several respondents, and recent evidence indicates that increased cooperation within and among professions has been a positive outcome of interprofessional education (21,22).

Many respondents described the need for resources to implement further pain curricula development. Common suggestions included the need for national data banks of cases, modules and presentation materials, as well as for a roster of health professionals with pain education experience.

There are several limitations to the present survey. The purpose of this preliminary work was to examine the number of hours dedicated to pain content to provide a basis for future research. While disciplines were chosen with the largest number of students entering the workforce, the survey did not include other disciplines that also contribute to the health care team. The questions were developed from previous research (18,19) but the categories were expanded to eight content areas used in the 20 h curriculum evaluation model. However, some respondents stated they had difficulty attributing hours to some categories or that there was overlap. The respondent completing the survey may not have been the most knowledgeable person to complete the survey at all sites. In future research, a more standardized approach will be required to ensure a more systematic review.

It is noteworthy that curricula are shaped by academic accrediting and professional regulatory bodies through the regulations they impose. Students must acquire the necessary professional competencies to eventually become licensed by their respective colleges. These competencies tend to be given high priority by academic administrators and curriculum committees. However, a recent survey demonstrated minimal to no pain-related entry-to-practice competencies required for Canadian health science students (23). These data indicate that a baseline understanding of pain assessment and management knowledge, skills and judgement is not recognized as a priority in most of the documents of six health science disciplines surveyed. In contrast, pain competencies for graduates from veterinary colleges were found to be specific to pain assessment and management, and offered clear criteria for evaluating knowledge, skills and judgement. Standards for professional competence delineate important domains of professional practice and direction for learning (24). Therefore, influencing professional bodies to increase the number of required entry-to-practice pain management competencies may ultimately have the greatest impact on curricula.

SUMMARY

Prelicensure pain education is a critical step in ensuring that health care practitioners entering the workforce are competent in pain management. However, only one-third of this sample could identify designated pain content hours in their prelicensure health science curricula. While pain teaching was assumed to be ‘integrated’ in other courses, it was not quantifiable and therefore not able to be determined for two-thirds of respondents. Many respondents commented on the need for pain-related curriculum resources and interprofessional opportunities in this area. In contrast, veterinary programs reported considerably more focus on pain assessment and management in their curricula. Graduates from health science faculties caring for people should have as much pain content and related competency requirements as graduates from veterinary colleges. Future research is needed to examine models that can support increased pain content in heath science curricula.

Acknowledgments

This survey was supported by funding from the Canadian Pain Society. The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr Jessica Petersen for her assistance with data analysis and the educators at each university for the time taken to complete the survey.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sessle B. Incoming President’s address: Looking back, looking forward. In: Devor M, Rowbotham MC, Wisenfield-Hallin Z, editors. Progress in Pain Research and Management, Proceedings of the 9th World Congress on Pain. Vol. 16. Seattle: IASP Press; 2003. pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter J, Watt-Watson J, McGillion M, et al. An Interfaculty Pain Curriculum: Lessons learned from six years experience. Pain. 2008;140:74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watt-Watson J, Hunter J, Pennefather P, et al. An integrated undergraduate pain curriculum, based on IASP curricula, for six health science faculties. Pain. 2004;110:140–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leila NM, Pirkko H, Eeva P, Eija K, Reino P. Training medical students to manage a chronic pain patient: Both knowledge and communication skills are needed. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:167–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poyhia R, Niemi-Murola L, Kalso E. The outcome of pain related undergraduate teaching in Finnish medical faculties. Pain. 2005;115:234–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson JF, Brockopp GW, Kryst S, Steger H, Witt WO. Medical students’ attitudes toward pain before and after a brief course on pain. Pain. 1992;50:251–6. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90028-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rochman DL. Student’s knowledge of pain: A survey of four schools. Occup Ther Int. 1998;5:140–54. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simpson K, Kautzman L, Dodd S. The effects of a pain management education program on the knowledge level and attitudes of clinical staff. Pain Manag Nurs. 2002;3:87–93. doi: 10.1053/jpmn.2002.126071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strong J, Tooth L, Unruh A. Knowledge about pain among newly graduated occupational therapists: Relevance for curriculum development. Can J Occup Ther. 1999;66:221–8. doi: 10.1177/000841749906600505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unruh A. Teaching student occupational therapists about pain: A course evaluation. Can J Occup Ther. 1995;62:30–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barr H, Freeth D, Hammick M, Koppel I, Reeves S. The evidence base and recommendations for interprofessional education in health and social care. J Interprof Care. 2006;20:75–8. doi: 10.1080/13561820600556182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education Interprofessional education: The definition. <http://www.caipe.org.uk/about-us/defining-ipe/> (Version current at October 21, 2009).

- 13.D’Amour D, Oandasan I. Interprofessionality as the field of interprofessional practice and interprofessional education: An emerging concept. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):8–20. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horsburgh M, Perkins R, Coyle B, Degeling P. The professional subcultures of students entering medicine, nursing and pharmacy programmes. J Interprof Care. 2006;20:425–31. doi: 10.1080/13561820600805233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson CL, Nicholson C, Davidson B, McGuire T. Training the primary care team – a successful interprofessional education initiative. Aust Fam Physician. 2006;35:829–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lax L, Watt-Watson J, Pennefather P, Hunter J, Scardamalia M. The Pain Week E-Learning Project: An undergraduate interprofessional knowledge building initiative. J Pain. 2007;4(2 Suppl 1):726. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barr H, Hammick M, Koppel I, Reeves S. Systematic review of the effectiveness of interprofessional education: Towards transatlantic collaboration. J Allied Health. 1999;28:104–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graffam S. Pain content in the curriculum: A survey. Nurs Educator. 1990;15:20–3. doi: 10.1097/00006223-199001000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watt-Watson J, Watson CPN. Research: Pain curriculum. Can Nurs. 1989;85:45–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Association for the Study of Pain <http://www.iasp-pain.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Curricula&Template=/CM/HTMLDisplay.cfm&ContentID=1952> (Version current at March 28, 2009).

- 21.Carr EC, Brockbank K, Barrett RF. Improving pain management through interprofessional education: Evaluation of a pilot project. Learn Health Soc Care. 2003;2:6–17. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reeves S. A systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education on staff involved in the care of adults with mental health problems. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2001;8:533–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1351-0126.2001.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watt-Watson J, Peter E, Hayward M, Carlsson L. Entry to practice pain competencies: Survey of requirements for health science students. Pain Res Manage. 2008;13:152. (Abst) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein R, Hundert E. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287:226–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]