Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery is performed more frequently in individuals who are older and sicker than in previous years. Increased patient acuity and reduced hospital length of stays leave individuals ill prepared for their recovery.

OBJECTIVES:

To test the feasibility of a peer support program and determine indicators of the effects of peer support on recovery outcomes of individuals following CABG surgery.

METHODS AND RESULTS:

A pre-post test pilot randomized clinical trial design enrolled men and women undergoing first-time nonemergency CABG surgery at a single site in Ontario. Patients were randomly assigned to either usual care or peer support. Patients allocated to usual care (n=50) received standard preoperative and postoperative education. Patients in the peer support group (n=45) received individualized education and support via telephone from trained cardiac surgery peer volunteers for eight weeks following hospital discharge. Most (93%) peer volunteers believed they were prepared for their role, with 98% of peer volunteers initiating calls within 72 h of the patient’s discharge. Peer volunteers made an average of 12 calls, less than 30 min in duration over the eight-week recovery period. Patients were satisfied with their peer support (n=45, 98%). The intervention group reported statistical trends toward improved physical function (physical component score) (t [89]=−1.6; P=0.12) role function (t [93]=−1.9; P=0.06), less pain (t [93]=1.30; P=0.20) and improved cardiac rehabilitation enrollment (χ2=2.50, P=0.11).

CONCLUSIONS:

These preliminary results suggest that peer support may improve recovery outcomes following CABG. Data from the present pilot trial also indicate that a home-based peer support intervention is feasible and an adequately powered trial should be conducted.

Keywords: Convalescence, Coronary artery bypass, Quality of life, Social support

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Le pontage aortocoronarien (PAC) est plus fréquent chez des personnes plus âgées et plus malades que par le passé. Une activité accrue des patients et une hospitalisation moins longue préparent mal les patients à leur rétablissement.

OBJECTIFS :

Utiliser un projet pilote pour évaluer la faisabilité d’un programme d’entraide par les pairs et déterminer les indicateurs des effets de l’entraide par les pairs sur le rétablissement des patients après un PAC.

MÉTHODOLOGIE ET RÉSULTATS :

On a fait participer des hommes et des femmes qui subissaient pour la première fois un PAC non urgent dans un seul établissement de l’Ontario afin de procéder à un essai clinique aléatoire pilote prélivraison. On a réparti aléatoirement les patients entre les soins habituels et l’entraide par les pairs. Les patients recevant les soins habituels (n=50) ont reçu la formation préopératoire et postopératoire habituelle. Les patients du groupe d’entraide par les pairs (n=45) ont reçu une formation et un appui téléphoniques personnalisés de la part de pairs volontaires formés en chirurgie cardiaque pendant huit semaines après le congé hospitalier. La plupart des pairs volontaires (93 %) se sentaient préparés à leur rôle, 98 % d’entre eux ayant amorcé les appels dans les 72 heures suivant le congé du patient. Les pairs volontaires ont fait une moyenne de 12 appels de moins de 30 minutes pendant la période de rétablissement de huit semaines. Les patients étaient satisfaits de cette entraide par les pairs (n=45, 98 %). Le groupe d’intervention a fait état de tendances statistiques vers une meilleure fonction physique (indice d’élément physique) (t [89]= −1,6, P=0,12), une meilleure fonction du rôle (t [93]= −1,9, P=0,06), une diminution de la douleur (t [93]= −1,30, P=0,20) et une augmentation de la participation à la réadaptation cardiaque (χ2=2,50, P=0,11).

CONCLUSIONS :

Ces résultats préliminaires laissent supposer que l’entraide par les pairs peut améliorer le rétablissement après un PAC. Les données du présent projet pilote indiquent également que l’intervention d’entraide par les pairs à domicile est faisable. Un essai d’une portée suffisante devrait être effectué.

Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery is an effective and safe treatment option for individuals with coronary artery disease (CAD), who are older and sicker than in previous years (1). Individuals undergo CABG surgery to relieve symptoms, improve health-related quality of life (HRQL) and reduce early death. However, following surgery, recovery and rehabilitation can be difficult. One week after discharge, 50% to 82% of individuals report pain and impaired function, with 66% still reporting difficulties at five weeks (2,3). This period offers an opportunity for health professionals to exert positive effects on health-related behaviours that may have long-term beneficial effects.

Existing support structures fail to address these early discharge concerns (4). Short hospital stays limit the time available to prepare patients adequately for their transfer home and for the early postdischarge period. In addition, regionalization of cardiac care to designated centres presents particular challenges for postoperative follow-up care in large geographical regions, where distance and geography restrict access for many patients. Peer support has been shown to be an effective intervention for a variety of populations, with beneficial effects across a wide spectrum of health outcomes (5,6). Peer volunteers have similar characteristics and possess specific knowledge that is concrete, pragmatic and derived from shared experiences. To address the barriers related to access of programs related to distance and geography, a home-based peer education and support program, delivered by telephone, needs to be investigated. However, before an adequately powered randomized clinical trial can be designed for this population, important questions must be answered in a pilot trial.

The objectives of the present pilot trial were to test the feasibility of all procedures, specifically to determine an estimate of recruitment rates, peer volunteer compliance and the intervention dose (number of calls), peer volunteer satisfaction with the orientation session and training manual, peer support activities offered to patients, and patients’ satisfaction with peer support. Exploratory questions helped determine indicators of the effects of peer support on HRQL, pain and pain-related interference with activities, and cardiac rehabilitation enrollment.

METHODS

Before recruitment, ethics approval was obtained from the Hospital Research Ethics Board and the Health Sciences I Research Ethics Board at the University of Toronto (Toronto, Ontario). Peer volunteers were recruited during February and March 2006 via letters, advertisements in local newspapers and posters displayed at the local outpatient cardiac rehabilitation program. Peer volunteers included men and women who had undergone CABG surgery within the previous five years, were able to communicate by telephone and had attended a cardiac rehabilitation program. Peer volunteers were screened for their ability to engage in conversation, impart information clearly, share experiences and display appropriate listening skills.

Patients were recruited between April 2006 and February 2007. Patients included men and women who were having first-time nonemergency CABG surgery, ready for discharge home and able to communicate via telephone. After written informed consent was obtained preoperatively, eligibility criteria were reconfirmed before discharge home, and baseline and demographic data were obtained; patients were then randomly assigned to the usual care group (UCG) or the peer support group (PSG). Random assignment was centrally controlled using an Internet-based randomization service (www.randomize.net) with stratification based on sex, using variable block sizes of four and eight. Patients and peer volunteers were matched by sex and as closely by age as possible.

UCG

Patients allocated to the UCG received preoperative and postoperative education, and visits from in-hospital peer volunteers.

PSG

In addition to usual care, patients randomly assigned to the PSG received peer-generated telephone calls for eight weeks following hospital discharge. Peer volunteers used the usual care materials to focus their telephone conversations on pain management, exercise and encouragement to attend a cardiac rehabilitation program. The intervention was standardized in that peer volunteers participated in a 4 h training session to clarify and review content materials of usual care, develop skills required for effective telephone support, understand when and how to facilitate appropriate referrals to health professionals, and demonstrate learning through role-playing and strategizing exercises; support was initiated within 72 h of hospital discharge; and support continued for a period of eight weeks. Peer volunteers also received a training manual intended to guide the training sessions and the intervention. The manual was based on those used in other peer support programs (7–11). The dose and frequency of the calls were determined by the peer-patient dyad at each telephone interaction and all telephone calls were to be peer-initiated.

Outcomes

Feasibility measures included the Peer Activity Log, the Peer Recruitment and Training Evaluation Survey, and the Peer Support Evaluation Inventory. Peer volunteers completed a Peer Activity Log for each patient randomly assigned to the PSG and returned it at the completion of each patient-peer experience. The Peer Activity Log provided information related to peer compliance (percentage of calls made to patients within 72 h of hospital discharge) and dose of the intervention (number of calls made during the eight weeks), as well as the support activities provided to patients during each telephone call. It was modelled after the peer volunteer activity logs used in other peer support trials (5,7). Support activities were modified for use in this trial and were consistent with the goals of the intervention. Peer volunteers completed a Peer Recruitment and Training Evaluation at the conclusion of their training session. Data from the Peer Support Evaluation Inventory were collected by the research assistant (RA) via telephone interview at nine weeks. Content validity of the original inventory was assessed by three North American social support experts and all subscales had a reported internal consistency of alpha greater than 0.91 (12).

The RA, blinded to group allocation, collected all exploratory outcome data via telephone interview at nine weeks. The primary exploratory outcome for the present pilot trial was HRQL, specifically the physical component score (PCS) of the SF-36v2 (acute form) (QualityMetric Incorporated, USA). The PCS has the closest conceptual link to peer support and has been reported to be a significant predictor of six-month mortality following CABG surgery after adjustment for known risk factors (13). The SF-36v2 has an internal consistency of 0.76 to 0.94 (14,15) and excellent evidence of construct, criterion and predictive validity (14). HRQL was measured at baseline (preoperatively [T1]) and at nine weeks (T2) to compute mean change scores (T2 minus T1) and mean differences (Δ) in change scores between groups (PSGΔ minus UCGΔ). Other exploratory outcomes included pain and pain-related interference with activities, and cardiac rehabilitation enrollment. Pain intensity and quality were measured using the McGill Pain Questionnaire – Short-Form. The McGill Pain Questionnaire – Short Form has well-established reliability and validity (16). The Brief Pain Inventory interference subscale was used to measure pain-related interference with activities. The reliability of the interference subscale ranged from 0.86 to 0.91 (16). The Brief Pain Inventory interference subscale has both discriminant (17) and construct validity (18,19), and has detected clinically important differences related to the introduction of an educational strategy for individuals about to undergo CABG surgery (19). Cardiac rehabilitation enrollment was used to determine the number of patients who had been referred for outpatient cardiac rehabilitation and who had attended at least one session of the program.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SAS 9.1 software (SAS Institute Inc, USA). Because the present study was a pilot study, the focus of the analyses was on descriptive statistics rather than formal tests of hypotheses. For preliminary analyses, mean differences in change scores between groups (PSGΔ minus UCGΔ) were computed for each of the eight domains and the two summary scores and t tests used to detect significant group differences. Other exploratory outcomes and feasibility data were assessed at nine weeks only. Properties of their distribution were assessed by group, including the mean and variance for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Trends were reported for P≤0.2. Treatment effects were compared by subgroups to identify possible factors that may form stratification factors for the larger trial. Missing data patterns were described in detail and characteristics of patients who dropped out were compared with completers.

Because this was a pilot trial, enrollment was restricted to 100 patients (50 patients per group). A sample of 50 patients per group allowed us to estimate continuous measures to within 0.28 SDs, 19 times out of 20. If it was assumed that the SF-36 physical and mental summary scales had an SD of 10 points, as they do with the general United States population, this provided 95% CIs with an average width of ±2.8 points. More importantly, the basis for an informed sample size calculation would be formed for a larger trial.

RESULTS

Baseline patient characteristics are reported in Table 1. The mean (± SD) age of the UCG was 64±10 years (range 41 to 85 years) and the mean age of the PSG was 62±11 years (range 40 to 84 years). The most common comorbid conditions were angina (UCG n=40 [77%]; PSG n=33 [67%]), myocardial infarction (MI) (UCG n=28 [54%]; PSG n=27 [55%]) and upper gastrointestinal disease (UCG n=23 [44%]; PSG n=16 [33%]). Baseline characteristics of patients not randomly assigned (n=5) were similar to those who were randomly assigned. Of the 14 peer volunteers, 11 were men, all were married, nine had community postsecondary education and all were retired. The mean age of peer volunteers was 69±5 years (range 61 to 77 years).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Baseline characteristics | UCG (n=52), n (%) | PSG (n=49), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 43 (83) | 41 (84) |

| Female | 9 (17) | 8 (16) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 38 (73) | 42 (86) |

| Divorced/widowed/single | 13 (25) | 7 (14) |

| No response | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Level of education | ||

| Less than high school | 10 (19) | 6 (12) |

| High school | 22 (42) | 10 (20) |

| College/university | 18 (35) | 26 (53) |

| No response | 2 (4) | 7 (15) |

| Employment | ||

| Full-time | 18 (35) | 17 (35) |

| Part-time | 5 (9) | 1 (2) |

| Not employed | 28 (54) | 29 (59) |

| No response | 1 (2) | 2 (4) |

| Canadian Cardiovascular Society functional class | ||

| I | 0 (0) | 4 (8) |

| II | 11 (21) | 5 (10) |

| III | 18 (35) | 12 (25) |

| IV | 8 (15) | 4 (8) |

| No response | 15 (29) | 24 (49) |

| Left ventricular function grade | ||

| I | 32 (62) | 20 (41) |

| II | 15 (29) | 24 (49) |

| III | 4 (7) | 5 (10) |

| IV | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| No response | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

‘No response’ indicates that information was not available in the patient record. PSG Peer support group; UCG Usual care group

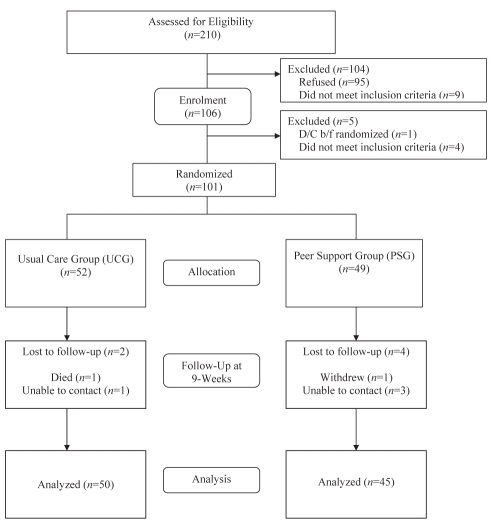

Of 210 patients screened preoperatively, 95 refused and 106 consented to participate (Figure 1). Nine patients were ineligible preoperatively because they were scheduled to be transferred postoperatively to a facility other than their home. Five recruited patients did not meet the eligibility criteria postoperatively and were not randomly assigned. Thus, 101 patients were randomly assigned to the UCG or the PSG at hospital discharge. Six patients did not complete outcome measures, yielding an 8% loss to follow-up in the PSG and a 4% loss to follow-up in the UCG.

Figure 1).

Patient flow chart. b/f Before; D/C Discharged

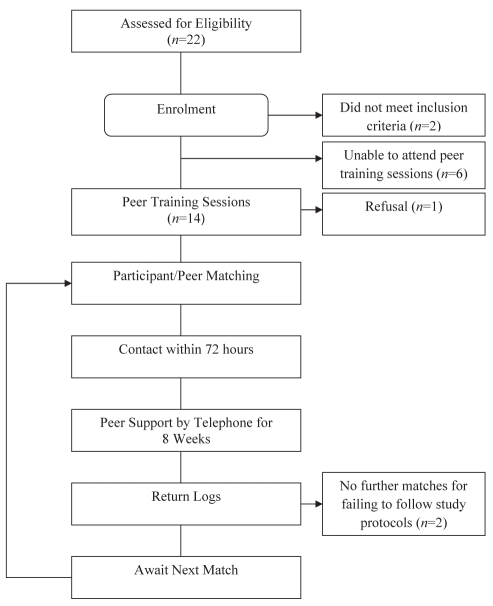

One hundred seventy-two letters were sent to men and women who had undergone CABG surgery and attended cardiac rehabilitation within the past five years. Of 22 peer volunteers screened, two women were ineligible (combined CABG surgery and valve surgery) and six were unable to attend one of the peer-training sessions (Figure 2). The remaining 14 peer volunteers participated in one of the three 4 h training sessions offered. One peer volunteer declined to participate following the training session. Two peer volunteers, who failed to return log sheets as directed after delivering the telephone intervention to a total of four patients, were not matched again. Of the 14 peer volunteers able to attend a training session, 13 (93%) reported the training session adequately prepared them for their peer volunteer Can J Cardiol Vol 25 No 12 December 2009 role. Most (n=12 [86%]) indicated they received adequate information to support their peer volunteer experience.

Figure 2).

Peer volunteer flow chart

Most peer volunteers (98%) initiated calls to patients within 72 h of discharge. The mean duration of a telephone call was 15.7±12.6 min, with 94% (n=368) being less than 30 min. Although no sex differences were evident in the length of telephone calls, men completed an average of eight contacts per patient (302 logs per 39 patients), while women completed an average of 15 contacts per patient (91 logs per six patients). Confirmed contacts (n=539) made by the peer volunteers included 393 connections and 146 attempted connections, with a response rate of 92% for returned logs (539 of 585 possible logs). Possible logs were estimated based on two peer volunteers (one man and one woman) supporting two patients each:

Each peer volunteer supported four patients (1:4) and activities most commonly reported were listening to concerns (n=332 [85%]), discussing walking (n=323 [83%]), and encouraging achievements (n=289 [74%]) and rest periods (n=288 [73%]). Men more frequently provided ‘matter-of-fact’ information such as advice on walking (n=265 [88%]); women more frequently provided emotional support such as encouraging achievements (n=81 [89%]) and rest periods (n=81 [89%]).

Patients (n=46 [100%]) indicated that their peer volunteer helped them believe that they were not alone. Most (n=45 [98%]) thought their peer volunteer provided practical information, listened to their feelings and concerns, and helped them believe what they were going through was normal. Patients (n=46 [100%]) found their peer volunteer was respectful and they liked the support over the telephone. Overall, most patients (n=45 [98%]) were satisfied with their peer support experience.

Exploratory

At baseline, PCS scores for the UCG (mean 41.2±11.0) and the PSG (mean 40.5±11.3) were lower than the Canadian norms (n=2271) of 49.0±9.2 for men and women 55 to 64 years of age (20), and below that of individuals with a mean age of 67±6 years (n=25) after a similar duration (74±30 days) post-CABG surgery (mean 42.4±7.4) (21). At nine weeks, the PCS scores for the UCG (mean 44.6±9.2) and PSG (mean 47.5±8.2) remained below the Canadian norm (n=2271) of 49.0±9.2 (20), but were better than the older but otherwise comparable sample of individuals post-CABG surgery (mean 42.4±7.4) (21). Mean change scores (T2 minus T1) and mean differences in change scores between groups (PSGΔ minus UCGΔ) were computed, and t tests were used to detect significant differences in change between groups on domain and summary scores (Table 2). There was a trend toward greater improvement in the role-physical domain (t [93]=−1.9; P=0.06) and in PCS (t [89]=−1.6; P=0.12) scores for PSG.

TABLE 2.

Independent samples t test for significant differences in change scores on the SF-36v2* (acute form)

| Variable |

Δ (T2 – T1) |

Mean difference between groups |

t (df) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCG | PSG | PSGΔ – UCGΔ | |||

| PF | 14.9±30.3 | 22.6±33.9 | 7.7±32.1 | −1.2 (94) | 0.24 |

| RP | 14.8±34.7 | 28.8±37.9 | 14.0±36.3 | −1.9 (93) | 0.06 |

| BP | 7.5±35.5 | 8.6±26.9 | 1.0±31.8 | −0.2 (91) | 0.88 |

| GH | 2.8±18.8 | 7.7±20.2 | 4.9±19.5 | −1.2 (92) | 0.23 |

| PCS | 3.2±11.9 | 7.2±11.7 | 3.9±11.8 | −1.6 (89) | 0.12 |

| MH | 13.6±21.0 | 12.0±19.6 | −1.6±20.3 | 0.4 (93) | 0.70 |

| RE | 16.1±33.9 | 12.0±39.6 | −4.0±36.7 | 0.5 (93) | 0.59 |

| SF | 20.0±31.0 | 23.6±34.6 | 3.6±32.8 | −0.5 (93) | 0.59 |

| VT | 12.6±29.8 | 11.8±22.8 | −0.8±26.7 | 0.2 (93) | 0.88 |

| MCS | 8.6±12.9 | 5.3±12.3 | −3.3±12.6 | 1.2 (89) | 0.22 |

Data presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated.

QualityMetric Incorporated, USA. Δ Change; BP Bodily pain; df Degrees of freedom; GH General health; MCS Mental component score; MH Mental health; PCS Physical component score; PF Physical functioning; PSG Peer support group; RE Role-emotional; RP Role-physical; SF Social functioning; T1 Baseline; T2 Nine weeks; UCG Usual care group; VT Vitality

Twenty-six patients (27%) reported moderate to severe numeric rating scale scores for ‘worst pain’ in the previous 24 h (Table 3), with those in the PSG having lower pain scores (t [93]=1.30; P=0.20). One-quarter (n=24 [25%]) of the sample described their pain as discomforting, distressing, horrible and excruciating (McGill Pain Questionnaire Present Pain Intensity); most (n=15 [30%]) were in the UCG versus the PSG (n=9 [20%]). There was also a trend for patients in the PSG to report less interference in walking (t [93]=1.53; P=0.13) and relations with others due to pain (t [93]=1.48; P=0.14). Seventeen (18%) patients had attended an outpatient cardiac rehabilitation program at nine weeks post-CABG surgery, including 11 (25%) in the PSG and six (12%) in the UCG (χ2=2.50, P=0.11).

TABLE 3.

Frequencies of moderate to severe pain scores (≥4/10) (‘now at rest’, ‘now with movement’ and the ‘worst pain in the previous 24 h with movement’) reported nine weeks following coronary artery bypass graft surgery

| Pain | UCG (n=50), n (%) | PSG (n=45), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Now at rest | 6 (12) | 1 (2) |

| Now with movement | 11 (22) | 5 (11) |

| Worst pain in previous 24 h with movement | 15 (30) | 11 (24) |

UCG Usual care group; PSG Peer support group

DISCUSSION

Low social support, as indicated by a relatively low level of social interaction and few social ties, has been associated with up to a 50% increase in mortality following an MI (22). Peer support programs are based on the premise that support from others who have been through a similar experience can reduce the negative sequelae associated with a disease or condition. In a recent review, consistent benefits, including high participant satisfaction, were evident in peer support programs delivered to individuals with cancer (23). Moreover, peer support delivered by telephone and the Internet was reported to be particularly beneficial to patients who were homebound, geographically distant and/or desiring privacy. Only six studies reported on peer support interventions among individuals with heart disease. Samples included mostly younger men (mean age 58 years) following first-time CABG surgery (24,25). The amount of peer training varied between trials, from 45 min of a tape or slide show (25) to a series of five classes taught over two weeks (26). There was a wide range in the number of contacts a peer had with an individual, ranging from one to 37 (26), and there were considerable differences in the number of peer volunteers available to deliver the intervention, ranging from two (27) to 45 (28), with a peer to individual ratio ranging from 1:164 (27) to 1:1 (28). Only one study (27) stated that both the content and delivery of the intervention were standardized. Most of the studies reported multiple measures of effect and many did not specify a primary outcome.

The methods used in the present pilot trial were robust, and addressed the conceptual and methodological weaknesses noted in previous studies using peer support interventions for individuals with heart disease (24–28). Random assignment was centrally controlled using an Internet-based randomization service. The peer support intervention was administered only to those patients in the PSG, minimizing the risk of contamination. There was no control over patients in either the UCG or PSG receiving support from family or friends who had previously undergone CABG surgery. This cointervention could have occurred in a similar fashion to participants in both treatment groups. However, this cointervention (lay support) is conceptually distinct from the peer support intervention and therefore does not threaten the integrity of the pilot trial results. There was less than 10% attrition in both groups. The RA was blinded to group allocation during data collection and assessment. Measurement biases were reduced by the use of standardized and reliable outcome measures. Data were entered into a Microsoft Access (Microsoft Corporation, USA) database, and logic and range checks verified the accuracy of the data. Double date entry was performed for all primary outcome data and 20% of all secondary outcome data. Intention-to-treat analyses ensured all participants remained in the group to which they were randomly assigned for analysis of data.

Implications

A peer support program delivered by telephone is feasible and particularly important for individuals who live in large geographical areas, where distance and geography restrict access to specialized services. The trend in the present pilot trial for the PSG at nine weeks post-CABG surgery of having greater improvement in role-physical functioning and PCS than the UCG, including walking and climbing stairs, and performing daily activities and work, is important. In primary prevention studies, individuals who reported increased levels of physical activity and fitness were found to have a greater than 50% reduction in RR of death from any cause and death due to cardiovascular disease (29). The benefits of physical activity and fitness were also evident in secondary prevention trials (30,31). Physical activity and fitness were found to be effective in slowing the progression of CAD and reducing plaque in patients with established heart disease (32). Physical inactivity is a modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease and a variety of other chronic diseases including diabetes, obesity, hypertension and depression (33,34). The prevalence of physical inactivity has been reported as 51% among adult Canadians, higher than that of all other modifiable risk factors (35). Home-based peer support may be an effective intervention used to improve physical activity and fitness in the cardiovascular population, as well as other populations, including diabetes, obesity, hypertension and depression. Adequately powered trials in primary and secondary prevention need to be undertaken to determine whether peer support could be used to promote health in the CABG surgery and other chronic disease populations.

The physical and psychosocial benefits of formal cardiac rehabilitation programs have been well established and include maintaining functional status, enhancing feelings of well-being, increasing work capacity and ability to relax, improving self-image, and decreasing anxiety and depression (36–39). A systematic review and meta-analysis of 48 trials revealed that, compared with usual care, cardiac rehabilitation significantly reduced the incidence of premature death from any cause and death due to cardiovascular disease (40). Intake is not typically offered until eight weeks after CABG surgery, with only one-third of individuals participating (41), and only one-third of these attending for six months (41). Carroll et al (10) conducted a randomized clinical trial and found significantly more patients enrolled and attended a cardiac rehabilitation program at three, six and 12 months following an MI and CABG surgery if they received a peer advisor or advanced practice nurse intervention. In a recent Cochrane review, Mistiacen and Poot (42) found inconclusive evidence for telephone follow-up by hospital-based health professionals among 5110 patients discharged from hospital to home. Other care delivery models, including home-based peer support, may prove to be beneficial in supporting the recovery needs of individuals following CABG surgery. That is, peer volunteers are ideally positioned to provide support and ensure adequate progress in activity levels during the time from hospital discharge to intake into a cardiac rehabilitation program. Moreover, peer volunteers may provide sufficient guidance for individuals who are geographically isolated and not able to attend formal programs of cardiac rehabilitation.

A large number of patients declined to participate in the trial, reporting they were overwhelmed with having learned of their need for urgent or semiurgent CABG surgery. Among those who participated, the majority were satisfied with their peer support experience; they found that the information provided was practical and supportive, and the support by telephone was convenient. In future trials, resources need to be properly allocated so that clinical trial personnel can help patients understand their recovery needs before surgery, and the importance of planning and supporting the recovery experience following hospital discharge. Most of the peer volunteers reported the 4 h orientation and the peer training manual were appropriate, and that they were adequately prepared for their peer volunteer role. Additional time could be spent role-playing and covering sex differences related to the number and content of the telephone calls (ie, the more frequent and emotionally focused telephone calls for women). Peer volunteers had no difficulty making the initial contact with the participant within 72 h of hospital discharge. The average peer to patient ratio was 1:4, women made more calls than men and most of the calls were less than 30 min in duration. The focus of telephone calls was to listen to concerns, discuss walking, and encourage achievements and rest periods. It is important to ensure peer volunteers do not provide medical advice to patients. The orientation and peer training manual must contain information on patient education resources and referral processes, with consideration to the completion and monitoring of Peer Activity Logs in future trials.

CONCLUSION

CABG surgery is well established as an important revascularization procedure in the treatment of CAD. Increased patient acuity and reduced length of hospital stays leave individuals ill prepared for their recovery following discharge. Previous evidence suggested existing supports (including printed education materials, community care resources and nurse-initiated telephone follow-up) failed to address concerns of individuals in this early period following hospital discharge. The results of the present pilot trial suggest that a home-based peer education and support program, delivered by telephone, is feasible, and may improve recovery and enhance HRQL for individuals in the early weeks following CABG surgery. Peer volunteers may provide the necessary ‘link’ to health care resources and personnel for individuals in large geographical regions, where distance and geography restrict access. An adequately powered larger trial needs to be undertaken to determine the effect of home-based peer support, delivered by telephone, on recovery outcomes post-CABG surgery. Consideration should also be given to including individuals following percutaneous coronary interventions and determining the health care costs associated with such home-based peer education and support programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Tom Hart, Krista Smith, Elizabeth Spratt and Pamela Bart, who assisted with patient recruitment, data collection and data management. Andrew Day, Xuran Jiang and Wilma Hopman from the Clinical Research Centre at Kingston General Hospital (Kingston, Ontario) provided statistical expertise. The authors also thank the peer volunteers and patients, whose participation may help to improve the outcomes of others who undergo CABG surgery.

Footnotes

FUNDING: HSFC, Canadian Institutes of Health Research FUTURE Program for Cardiovascular Nurse Scientists, Cardiac Science Medtronic Research Grant/Kingston General Hospital, CCCN Research Grant, Nurse Practitioner Association of Ontario Cardiovascular Acute Care Nurse Practitioner Pfizer Award and a Canadian Pain Society Nursing Research Award.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION: NCT00275340.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ghali WA, Quan H, Shrive FM, Hirsch GM. Outcomes after coronary artery bypass graft surgery in Canada: 1992/93 to 2000/01. Can J Cardiol. 2003;19:774–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pain after cardiac surgery: An acute and/or chronic problem. APS/CPS Scientific Meeting, 2004; Vancouver. September 6, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tranmer JE, Parry MJE. Enhancing postoperative recovery of cardiac surgery patients. A randomized clinical trial of an advanced practice nursing intervention. West J Nurs Res. 2004;26:515–32. doi: 10.1177/0193945904265690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallagher R, McKinley S, Dracup K. Effects of a telephone counseling intervention on psychosocial adjustment in women following a cardiac event. Heart Lung. 2003;32:79–87. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2003.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dennis CL, Hodnett E, Gallop R, Chalmers B. The effect of peer support on breast-feeding duration among primiparous women: A randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2002;166:21–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim S, Koniak-Griffin D, Flaskerud JH, Guarnero PA. The impact of lay health advisors on cardiovascular health promotion. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;19:192–9. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200405000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dennis C. The effect of peer support on postpartum depression: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48:61–70. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canadian Cancer Society. Root of Support. 1997. (Pamphlet)

- 9.Carr R.Peer Resources Network<http://www.peer.ca/PRN.html> (Version current at October 27, 2009).

- 10.Carroll DL, Rankin SH, Cooper BA. The effects of a collaborative peer advisor/advanced practice nurse intervention. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;22:313–9. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000278955.44759.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parry M, Holland-Reilly J. ‘Helping Hearts’ In-Hospital Peer Support Program. 2004.

- 12.Dennis CL. The effect of peer support on postpartum depression: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48:115–24. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rumsfeld JS, MaWhinney S, McCarthy M, et al. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA. 1999;281:1298–303. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.14.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware JE. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and interpretation guide. Boston: New England Medical Center, The Health Institute; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irvine D, O’Brien-Pallas L, Murray M, et al. The reliability and validity of two health status measures for evaluating outcomes of home care nursing. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:43–54. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(200002)23:1<43::aid-nur6>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDowell I, Newell C. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. 2nd edn. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cleeland C. Pain assessment in cancer. In: Osoba D, editor. Effect of Cancer on Quality of Life. Florida: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 293–305. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watt-Watson J, Stevens B, Katz J, Costello J, Reid GJ, David T. Impact of preoperative education on pain outcomes after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Pain. 2004;109:73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watt-Watson J, Stevens B, Costello J, Katz J, Reid G. Impact of preoperative education on pain management outcomes after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Can J Nurs Res. 2000;31:41–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hopman WM, Towheed T, Anastassiades T, et al. Canadian normative data for the SF-36 health survey. CMAJ. 2000;163:265–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaPier TK. Functional status of patients during subacute recovery from coronary artery bypass surgery. Heart Lung. 2007;36:114–24. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, et al. A prospective study of social networks in relation to total mortality and cardiovascular disease in men in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1996;50:245–51. doi: 10.1136/jech.50.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell HS, Phaneuf MR, Deane K. Cancer peer support programs – do they work? Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parent N, Fortin F. A randomized, controlled trial of vicarious experience through peer support for male first-time cardiac surgery patients: Impact on anxiety, self-efficacy expectation, and self-reported activity. Heart Lung. 2000;29:389–400. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2000.110626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thoits PA, Hohmann AA, Harvey MR, Fletcher B. Similar-other support for men undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Health Psychol. 2000;19:264–73. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riegel B, Carlson B. Is individual peer support a promising intervention for persons with heart failure? J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;19:174–83. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200405000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Gonzalez VM. Hispanic chronic disease self-management. Nurs Res. 2003;52:361–9. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200311000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whittemore R, Rankin SH, Callahan CD, Leder MC, Carroll DL. The peer advisor experience. Qual Health Res. 2000;10:260–76. doi: 10.1177/104973200129118408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myers J, Kaykha A, George S, et al. Fitness versus physical activity patterns in predicting mortality in men. Am J Med. 2004;117:912–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Walker M. Physical activity and mortality in older men with diagnosed coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2000;102:1358–63. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.12.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jolliffe JA, Rees K, Taylor RS, Thompson D, Oldridge N, Ebrahim S. Exercise-based rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001:CD001800. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franklin BA, Swain DP. New insights in the prescription of exercise for coronary patients. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;18:116–23. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200304000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American College of Sports Medicine Position stand: Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:992–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blair SN, Brodney S. Effects of physical inactivity and obesity on morbidity and mortality: Current evidence and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31:S646–62. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199911001-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Canadian Community Health Survey. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morrin L, Black S, Reid R. Impact of duration in a cardiac rehabilitation program on coronary risk profile and health-related quality of life outcomes. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2000;20:115–21. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200003000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright DJ, Williams SG, Riley R, Marshall P, Tan LB. Is early, low level, short term exercise cardiac rehabilitation following coronary artery bypass surgery beneficial? A randomized controlled trial. Heart. 2002;88:83–4. doi: 10.1136/heart.88.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perski A, Osuchowski K, Andersson L, Sanden A, Feleke E, Anderson G. Intensive rehabilitation of emotionally distressed patients after coronary by-pass grafting. J Intern Med. 1999;246:253–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner SC, Bethell HJN, Evans JA, Goddard JR, Mullee MA. Patient characteristics and outcomes of cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2002;22:253–60. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor RS, Brown A, Ebrahim S, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for patients with coronary heart disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Medicine. 2004;116:682–92. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daly J, Sindone AP, Thompson DR, Hancock K, Chang E, Davidson P. Barriers to participation in and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs: A critical literature review. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2002;17:8–17. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2002.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mistiacen P, Poot E. Telephone follow-up, initiated by a hospital-based health professional, for postdischarge problems in patients discharged from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD004510. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004510.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]