Abstract

Background

The pathogenic fungus Paracoccidioides brasiliensis is the agent of paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM). This is a pulmonary mycosis acquired by inhalation of fungal airborne propagules that can disseminate to several organs and tissues leading to a severe form of the disease. Adhesion and invasion to host cells are essential steps involved in the internalization and dissemination of pathogens. Inside the host, P. brasiliensis may use the glyoxylate cycle for intracellular survival.

Results

Here, we provide evidence that the malate synthase of P. brasiliensis (PbMLS) is located on the fungal cell surface, and is secreted. PbMLS was overexpressed in Escherichia coli, and polyclonal antibody was obtained against this protein. By using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy, PbMLS was detected in the cytoplasm and in the cell wall of the mother, but mainly of budding cells of the P. brasiliensis yeast phase. PbMLSr and its respective polyclonal antibody produced against this protein inhibited the interaction of P. brasiliensis with in vitro cultured epithelial cells A549.

Conclusion

These observations indicated that cell wall-associated PbMLS could be mediating the binding of fungal cells to the host, thus contributing to the adhesion of fungus to host tissues and to the dissemination of infection, behaving as an anchorless adhesin.

Background

Paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM), the most important systemic mycosis in Latin America, is a chronic granulomatous disease that affects about 10 million people.

Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, a thermally dimorphic fungus pathogen, is the pulmonary infective agent [1,2]. This initial interaction appears to govern the subsequent mechanisms of innate and acquire immunity, which result in localized infection or overt disease [3].

The mechanisms of adherence and invasion have been studied extensively in pathogenic bacteria [4], and in pathogenic fungi such as Candida albicans [5], Histoplasma capsulatum [6] and Aspergillus fumigatus [7], and P. brasiliensis [8-10]. Fungi are non-motile eukaryotes that depend on their adhesive properties for selective interaction with host cells [11]. Adherence molecules are fundamental in pathogen-host interaction; during this event, the fungal cell wall is in continual contact with the host and acts as a sieve and reservoir for molecules such as adhesins [12]. The ability of P. brasiliensis to adhere to and invade nonprofessional phagocytes or epithelial cells has been recognized in previous studies [13-15]. Some P. brasiliensis adhesins such as gp43 [10], glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) [16], a 30 kDa protein [9], and triosephosphate isomerase (TPI) [17] have been described. Evidence for extracellular localization of some glycolytic enzymes lacking secretion signals at cell-wall anchoring motifs has been reported for some pathogens [18,19]. In addition malate synthase (MLS) is also described as an adhesin on Mycobacterium tuberculosis [20].

The glyoxylate cycle and its key enzymes isocitrate lyase (ICL) and MLS play a crucial role in the pathogenicity and virulence of various fungi such as the human pathogens A. fumigatus [21], Cryptococcus neoformans [22] and C. albicans [23,24], the bacterium M. tuberculosis [25-27] as well as the phytopathogenic fungus Magnaporthe grisea [28] and the necrotropic wheat pathogen Stagonospora nodorum [29]. A relevant role for the glyoxylate cycle in the viability and growth of fungi inside macrophages and, consequently, in the development of a disseminated fungal infection has been postulated [21]. ICL and MLS have also been considered a therapeutic target for the development of novel antifungal compounds, since there are no human orthologues. In P. brasiliensis, the enzyme MLS (PbMLS) participates in the glyoxylate pathway, which enables fungus to assimilate two-carbon compounds from the tricarboxylic acid cycle and in the allantoin degradation pathway of the purine metabolism, which allows the fungus to use nitrogen compounds [30].

Here it is demonstrated that PbMLS is the first fungal MLS localized on the cell surface which interferes with the infection process.

Results

Expression, purification and production of polyclonal antibody to PbMLSr

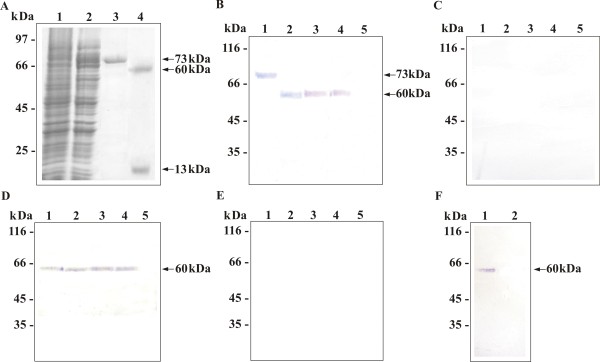

The cDNA encoding PbMLS was subcloned into the expression vector pET-32a to obtain recombinant fusion protein. The protein was not present in crude extracts of non-induced E. coli cells carrying the expression vector (Fig. 1A, lane 1). After induction with IPTG, a 73 kDa recombinant protein was detected in bacterial lysates (Fig. 1A, lane 2). The six-histidine residues fused to the N terminus of the recombinant protein were used to purify the protein from bacterial lysates by nickel-chelate affinity. The recombinant protein was eluted and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A, lane 3) and His-, Trx-, and S-Tag were removed by cleavage with the enterokinase (Fig. 1A, lane 4). An aliquot of the purified recombinant protein was used to generate rabbit polyclonal anti-PbMLSr antibody. Western blot confirmed the positive reaction of antibody with the fusion protein (Fig. 1B, lane 1) identifying a protein of 73 kDa. The cleaved recombinant protein was detected as a species of 60 kDa (Fig. 1B, lane 2).

Figure 1.

Localization of Pb MLSr. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of PbMLSr. E. coli BL21 C41 cells harboring the pET-32a-MLS plasmid were grown at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.6 and harvested before (lane 1) and after induction with 1 mM IPTG (lane 2). The cells were lysed by sonication, and the recombinant His-, Trx-, and S-Tagged PbMLS were isolated by affinity chromatography (lane 3). Tags were removed by EKMax™ Enterokinase digestion (lane 4). (B) Western blots of fusion PbMLSr (lane 1), cleaved PbMLSr (lane 2), crude extract proteins from yeast cells (lane 3), SDS-extracted yeast cell wall proteins (lane 4), and yeast cell wall proteins (lane 5). Proteins were probed with anti-PbMLSr antibody or with pre-immune rabbit (C). (D) Western blots of proteins of culture filtrate of P. brasiliensis yeast cells harvested after 24 h (lane 1), 36 h (lane 2), 7 days (lane 3), and 14 days (lane 4) of culture, and culture filtrate without P. brasiliensis as negative control (lane 5). Proteins were probed with anti-PbMLSr antibody or with pre-immune rabbit (E). (F) Western blots of peroxisomal fraction (lane 1) and mitochondrial fraction (lane 2) proteins from P. brasiliensis yeast cells were probed with anti-PbMLSr antibody. Molecular mass markers are indicated at the side.

Detection of PbMLS on cell wall extracts, culture filtrate, crude extract and peroxisomal fraction

To determine the subcellular distribution of PbMLS, cell wall-enriched, secreted, and peroxisomal fractions purified from P. brasiliensis yeast cells were obtained. Crude extract proteins, SDS-extracted cell wall proteins, and extracted cell wall proteins from yeast cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis, blotted onto nylon membrane and reacted to polyclonal anti-PbMLSr antibody. PbMLS was detected in crude extract (Fig. 1B, lane 3), and in SDS-extracted cell wall proteins (Fig. 1B, lane 4), but was not detected in extracted cell-wall proteins (Fig. 1B, lane 5). PbMLS activity was evaluated in SDS-extracted cell wall and in crude extract, showing specific activity of 2131.2 U/mg and 2051.28 U/mg, respectively. No cross-reactivity to the pre-immune rabbit serum was evidenced with the samples (Fig. 1C).

To determined whether PbMLS was secreted to the medium, proteins were extracted from culture filtrates harvested from P. brasiliensis which had been growing for 24 and 36 h (Fig. 1D, lanes 1 and 2, respectively), 7 days (Fig. 1D, lane 3), and 14 days (Fig. 1D, lane 4). The proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis, blotted onto nylon membrane and reacted to polyclonal anti-PbMLSr antibody. PbMLS was detected in all these preparations (Fig. 1D, lanes 1 to 4). No signal was detected in medium free of cells (Fig. 1D, lane 5). PbMLS activity was evaluated in culture filtrate showing specific activity of 1305.3 U/mg. No cross-reactivity to the pre-immune rabbit serum was evidenced with the samples (Fig. 1E). Altogether, these results suggest that PbMLS binds weakly to the cell wall and is actively secreted in P. brasiliensis.

Since PbMLS has the AKL tripeptide, a peroxisomal/glyoxysomal signal which targets PTS1 [31], the presence of the protein was investigated in this cellular compartment. Peroxisomal and mitochondrial fractions purified of P. brasiliensis were obtained. The proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis, blotted onto nylon membrane and reacted to the polyclonal anti-PbMLSr antibody. PbMLS was detected in the peroxisomal fraction (Fig. 1F, lane 1) confirming the localization of PbMLS in this organelle. Since PbMLS has not been found in mitochondria, the mitochondrial fraction was used as the negative control (Fig. 1F, lane 2).

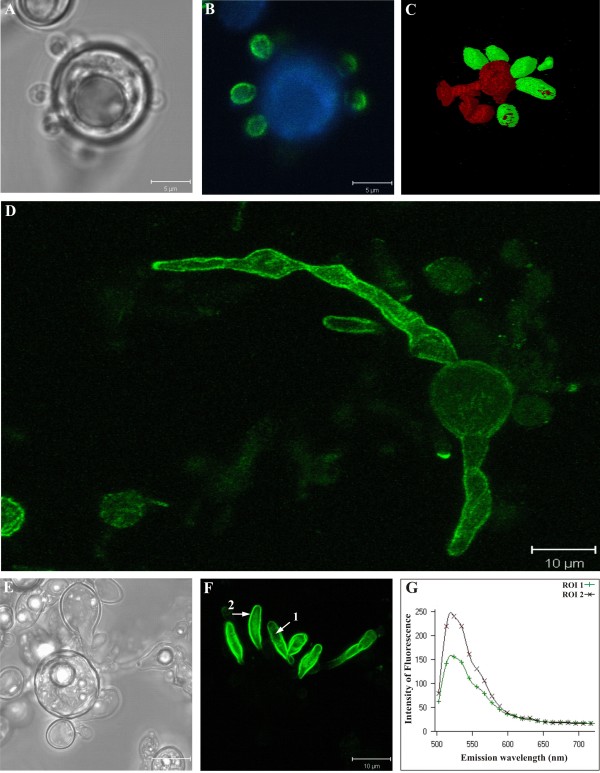

Cellular localization of PbMLS by confocal microscopy

To observe the cellular location of PbMLS, P. brasiliensis yeast cells were grown in rich medium and visualized by laser confocal microscopy. The expression of PbMLS was highly positive in the budding cells (Fig. 2 B, C and 2F) but was usually negative (Fig. 2 B and 2C) or weakly positive (Fig. 2 D) in the mother cells. Although reactivity was evident inside the cytoplasm of budding cells, it was much more intense on the cell surface (Fig. 2 F). The patterns and intensities of the fluorescence spectra of two regions of interest (ROI) are shown in Figure 2 G.

Figure 2.

Localization of Pb MLS by confocal laser scanning microscopy in P. brasiliensis yeast cells. Differential accumulation of PbMLS on the surface of budding cells is easily seen in B, C and F. Images A and E represent the differential interference contrast (DIC) of images B and F, respectively. Image C corresponds to a three-dimensional reconstruction of an immunofluorescent tomographic image showing the accumulation of PbMLS only on the budding cells and not in the mother. This is also observed in images B and F. Image G displays the fluorescence pattern and intensity of two regions of interest (ROI) specified by arrows 1 and 2 in image F, indicating that the fluorescence is more intense on the cell surface (2) than in the cytoplasm of budding cells (1). Image D shows a mother cell positive to PbMLS on the cellular surface and the formation, in culture, of budding cells also expressing PbMLS.

The localization of PbMLS was also evaluated on P. brasiliensis yeast cells grown in medium containing acetate or glucose as the sole carbon source. Yeast cells accumulated PbMLS in the presence of acetate (Fig. 3 B) or glucose (Fig. 3 D), but the quantity of PbMLS was higher when the fungus was cultivated in the presence of acetate. This disparity was exemplified by the fluorescence spectra (Fig. 3 E), representative of two ROIs indicated by arrows 1 and 2 (Fig. 3 B and 3D). No cross reaction was observed with the pre-immune serum (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Localization of Pb MLS by confocal laser scanning microscopy in P. brasiliensis yeast cells growing in different carbon sources. The same groups of cells grown in the presence of potassium acetate (images A and B) or glucose (images C and D) as the sole carbon source are shown, side by side, using differential interference contrast microscopy (DIC) and confocal immunofluorescence. In both situations, the accumulation of PbMLS was restricted to the budding cells. The graph in E displays, comparatively, the immunofluorescence patterns and intensities of two regions of interest (ROI 1 and 2), corresponding to arrows 1 and 2. The data indicate that, under the same labeling conditions, the budding cells cultivated on potassium acetate accumulate PbMLS more intensely on the cell surface than those grown on glucose.

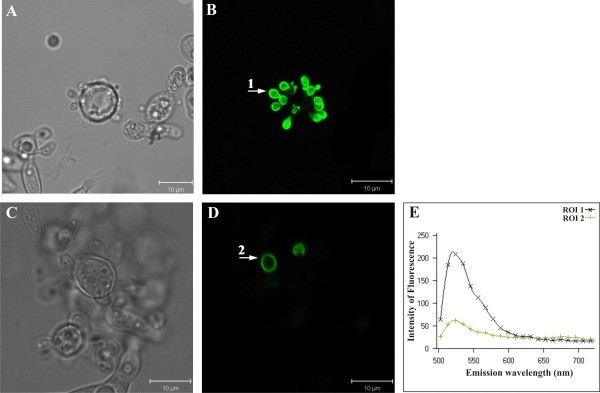

Binding of PbMLSr to extracellular matrix proteins (ECM) and the reactivity to sera of PCM patients

The ability of the PbMLSr to bind to ECM proteins was evaluated by Far-Western blot assays. PbMLSr binds to fibronectin, type I and IV collagen, but not to laminin as shown in Fig. 4A, lanes 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively). Negative controls were obtained incubating PbMLSr with the secondary antibody in the absence of ECM or PbMLSr with ECM only (Fig. 4A, lanes 5 and 6, respectively). The reaction between PbMLSr and the antibody anti-PbMLSr was used as a positive control (Fig. 4A, lane 7). The binding between PbMLS and ECM compounds was also evaluated by ELISA assay. The results reinforced that PbMLSr binds to fibronectin, type I and IV collagen (Fig. 4B). Negative controls were performed using PbMLSr (Fig. 4B) or ECM only (data not shown). The positive control was performed using anti-PbMLSr, anti-laminin, anti-fibronectin, anti-colagen I or anti-colagen IV antibody (data not shown).

Figure 4.

(A) Binding of Pb MLSr to ECM by Far-Western blot. PbMLSr (0.5 μg) was subjected to SDS-PAGE and electroblotted. Membranes were reacted with fibronectin (lane 1), type I collagen (lane 2), type IV collagen (lane 3) and laminin (lane 4), and subsequently incubated with rabbit IgG anti-fibronectin, mouse anti-type I and anti-type IV collagen antibodies, and anti-laminin, respectively. Peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG revealed the reactions. Negative control was obtained by incubating PbMLSr with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (lane 5), and PbMLSr with ECM (lane 6). Positive control was obtained by incubating PbMLSr with polyclonal anti-PbMLSr antibody (lane 7). (B) Binding of PbMLSr to ECM fibronectin, types I and IV collagen (10 μg/mL). The interaction was revealed by ELISA with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin. The results were expressed in absorbance units. The negative controls were performed using PbMLSr only. (C) Reactivity of PbMLSr to PCM patient sera. 1.0 μg of purified PbMLSr was electrophoresed and reacted to the sera of patients with PCM, diluted 1:100 (lanes 1 to 3) and to control sera, diluted 1:100 (lane 4). The positive control was obtained by incubating PbMLSr with its polyclonal antibody (lane 5). After reaction to the anti-human IgG alkaline phosphatase-coupled antibody (diluted 1:2000), the reaction was developed with BCIP-NBT. (D) Biotinylation assay by Western blot. Lysed A549 cells incubated with biotinylated PbMLSr (lane 1); Lysed A549 cells (lane 2) as negative control.

PbMLSr was reacted with three sera of patients with PCM and one serum from a healthy individual in immunoblot assays (Fig. 4C). Strong reactivity was observed with the PCM-patient sera (Fig. 4C, lanes 1 to 3). No cross-reactivity was observed with control serum (Figure 4C, lane 4). Reaction between PbMLSr and anti-PbMLSr was used as positive control (Fig. 4C, lane 5).

Binding of PbMLSr to pneumocytes

The ability of PbMLSr to bind to A549 cells was evaluated. PbMLSr was biotinylated and incubated with A549 cells. After lyses, proteins from A549 cells were electrophoresed by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto a membrane to perform Western blot with anti-PbMLSr antibody. A positive signal was detected from lysed pulmonary A549 cells treated with biotinylated PbMLSr (Fig. 4D, lane 1). The negative control was obtained using supernatant of A549 cells untreated with biotinylated protein (Fig. 4D, lane 2).

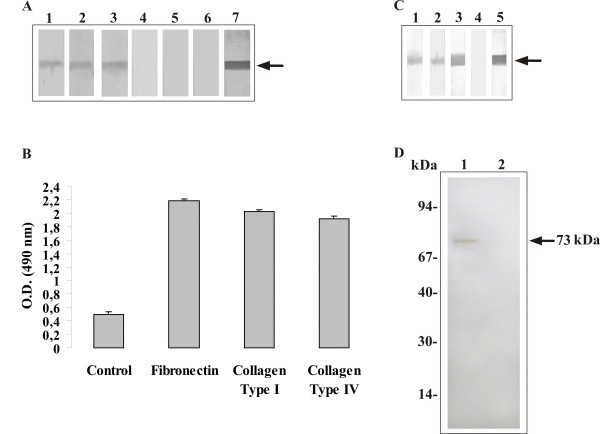

The inhibitory effect of PbMLSr and anti-PbMLSr antibody on the interaction of P. brasiliensis cells with pneumocytes

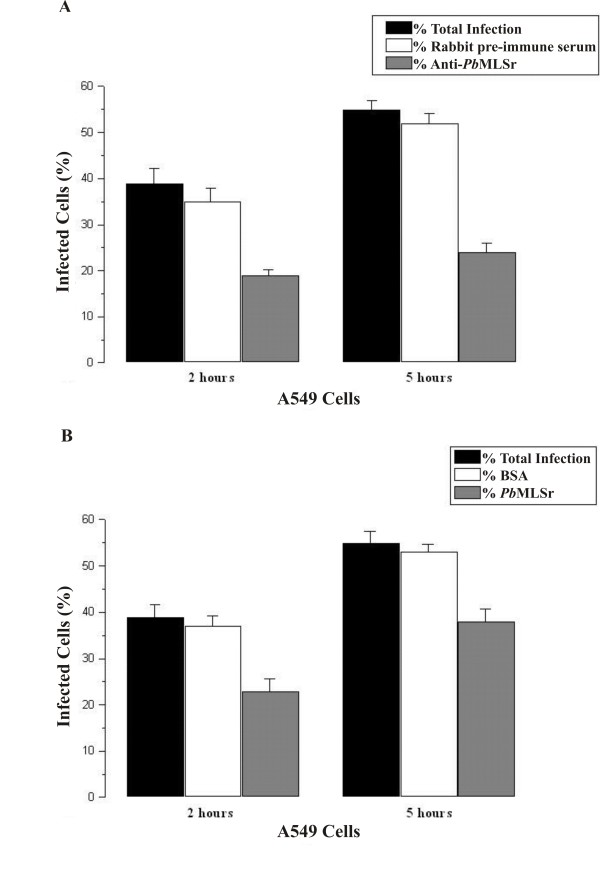

The infection index was determined by interactions between P. brasiliensis yeast cells and A549 pneumocytes, as shown in Figure 5. P. brasiliensis yeast cells were treated with the anti-PbMLSr antibody before interaction with pneumocytes or pneumocytes were treated with PbMLSr before interaction with P. brasiliensis. The controls (non-treated cells) were used to calculate the percentages of total infection. The interaction was analyzed by flow cytometry. Ten thousand events were collected to analysis as monoparametric histograms of log fluorescence and list mode data files. When P. brasiliensis yeast cells treated with anti-PbMLSr antibody were incubated with A549 cells, a decrease in infection was observed after 2 h and 5 h of incubation (Fig. 5A). Similarly, after treatment of A549 cells with PbMLSr, infection was reduced after 2 h and 5 h of incubation when compared to the values for non-treated cells (Fig. 5B). Controls were performed by incubating the pneumocytes with rabbit pre-immune serum or BSA before the addition of A549 cells or yeast cells (Fig. 5A and 5B, respectively).

Figure 5.

Interaction of P. brasiliensis yeast forms with pneumocytes. The interaction was assayed by indirect immunofluorescence and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) P. brasiliensis yeast cells were pretreated for 1 h with anti-PbMLSr polyclonal antibody (diluted 1:100), and control cells were pretreated with rabbit pre-immune serum. (B) A549 cells were pretreated for 1 h with 25 μg/mL of PbMLSr, and control pneumocytes were pretreated for 1 h with 25 μg/mL of BSA. Adhesion of P. brasiliensis to pneumocytes was analyzed 2 h after the treatments. Infection (adhesion plus internalization) of P. brasiliensis to pneumocytes was analyzed 5 h after the treatments.

Discussion

Our studies showed that PbMLS is a multifunctional protein; besides its enzymatic role as described by Zambuzzi-Carvalho [30], it could participate in the adherence process between the fungus and host cells through its ability to bind fibronectin, type I and type IV collagen. PbMLS was detected in crude extract, cell wall and culture filtrate of P. brasiliensis, which is confirmed by activity assay. Taken together, our results suggest that PbMLS is actively secreted by P. brasiliensis. In the same way, M. tuberculosis MLS has been consistently identified in the culture filtrates of mid-log phase M. tuberculosis cultures [32-34].

Adherence molecules are important in pathogen-host interactions. They operate as intercellular adhesion molecules (ICAM) or substrate adhesion molecules (SAM), contributing to cell-cell or cell-ECM adherences, respectively, and are usually exposed on the cellular surface. Successful host tissue colonization by fungus is a complex event, generally involving a ligand (adhesin) encoded by the pathogen and a cell or ECM receptor. The pathogen could interact with three types of host component: secreted cell products, host cell surface, or ECM proteins, such as types I and IV collagen, fibronectin, fibrinogen, and laminin [35]. The adhesin potential of PbMLS was demonstrated through Far-Western blot, ELISA and binding assays. These showed that the recombinant protein recognized the ECM proteins, fibronectin and types I and IV collagen, as well as pulmonary epithelial cells. This event indicates that PbMLS can play a role in the interaction of the fungus with host components. Studies have reported the capacity of P. brasiliensis for adhesion and invasion [9,15]. This is the first glyoxylate cycle enzyme identified on the fungal surface and released extracellularly which possesses the ability to bind to ECM proteins. The definition of PbMLSr as a surface-exposed ECM-binding protein, with an unknown mechanism for secretion from the cell or sorting proteins to cellular membrane, suggests that PbMLSr is compatible with anchorless adhesions [36,20]. In these types of adhesions, proteins are reassociated on the cellular surface after being secreted to execute their biological functions [36]. The presence of PbMLS in the culture filtrate harvested after 24 and 36 h, and 7 and 14 days of growth confirmed that it is truly a secreted protein. The presence of PbMLS in SDS-extracted cell-wall protein fraction indicates that PbMLS is associated with the cell surface through weak interactions. Taken together these results provide evidence that PbMLS may be transported out of the cell through the cell wall to be localized on the outer surface of the cell.

Reports have described the presence of some enzymes of the glycolytic pathway on the cell surface in P. brasiliensis as well as in other pathogens [16-19,37,38]. The presence of these housekeeping enzymes in unusual locations often correlates with their ability to perform alternative functions such as adherence/invasion of the host cells [38,18]. The ability of anti-adhesin antibodies to confer protection by blocking microbial attachment to host cells is being explored as a vaccination strategy in several microbial diseases [39-43]. The identification of the PbMLS as a probable adhesin has several implications. Understanding the consequences of the binding of PbMLS to host cells will lead to improved understanding of the initial events during infection. Further insights into the role of the PbMLS in the host-pathogen interaction could contribute to the design of novel therapeutic strategies for PCM control.

Although PCM infection starts by inhalation of airborne propagules of the mycelia phase, as conidia, which reach the lungs and differentiates into the yeast phase [2], we performed experiments just with yeast cells since this is the phase found inside the host. Is important emphasize that Pbmls transcript is also present in the mycelium phase as described [44,45].

The results of confocal laser scanning microscopy demonstrated differences in the accumulation of PbMLS among P. brasiliensis cells grown in different carbon sources. Accumulation of PbMLS was also higher in P. brasiliensis yeast cells than in the mycelial phase (data not shown). These findings were reinforced by the results of Felipe et al. [44], which suggested that the glyoxylate cycle is up-regulated in yeast cells [46]. Yeast cells grown on potassium acetate accumulated more PbMLS on the cell membrane than yeast cells grown on glucose. These results are in agreement with those obtained by Zambuzzi-Carvalho et al. [30] where the Pbmls transcript level was higher in yeasts cells grown in a two-carbon source than in cells grown on glucose only. The high intensity of ROI found in budding cells, mainly in the cellular membrane, suggests that the PbMLS is metabolically relevant and mainly synthesized by young cells (budding cells). It is unknown whether PbMLS plays any part in the differentiation and/or maturity processes of P. brasiliensis budding cells [45,47]. In fact, the glyoxylate pathway provides metabolic versatility for Candida albicans to utilize alternate substrata for development and differentiation and is involved in the formation of the filamentous state from the single cell state [23]. This process may help Laccaria bicolor grow toward the host with the aggressiveness required for mycorrhiza formation [48].

Conclusion

The results showed the presence of PbMLS in the culture filtrate of yeast cells (parasitic phase), its surface location in P. brasiliensis and its binding to ECM in Far-Western blot and ELISA assays and to A549 cells membranes. The reduction in the adherence of P. brasiliensis to A549 cells by anti-PbMLSr suggests that PbMLS could contribute to active fungal interaction and disease progression in humans through its ability to act as a probable adhesin. In addition, the absence of conventional secretion or cell wall anchoring motifs defines PbMLS as a probable anchorless adhesin that could contribute to virulence by promoting P. brasiliensis infection and dissemination.

Methods

P. brasiliensis isolate and growth conditions

The P. brasiliensis Pb01 isolate (ATCC-MYA-826) was previously investigated in our laboratory and was cultivated in semisolid Fava Netto's medium (1.0% w/v peptone, 0.5% w/v yeast extract, 0.3% w/v proteose peptone, 0.5% w/v beef extract, 0.5% w/v NaCl, 4% w/v glucose and 1.4% w/v agar, pH 7.2) as yeast cells for 7 days at 36°C.

Heterologous expression and purification of the PbMLS recombinant (PbMLSr)

The cDNA encoding to PbMLS was obtained by Zambuzzi-Carvalho et al. [30] (GenBank accession number:AAQ75800). EcoRI and XhoI restriction sites were introduced in oligonucleotides to amplify a 1617 bp cDNA fragment of the Pbmls, which encodes a predicted protein of 539 amino acids. The PCR product was subcloned into the EcoRI/XhoI sites of the pET-32a(+) expression vector (Novagen, Inc., Madison, Wis.). The resulting plasmid was transferred to Escherichia coli BL21 C41 (DE3). Bacteria transformed with the pET-32a-MLS were grown in LB medium supplemented with ampicillim (100 μ/mL) at 37°C until reaching the optical density of 0.6 at 600 nm. Synthesis of the recombinant protein was then initiated by adding isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to a final concentration of 1 mM to the growing culture and the bacterial extract was pelleted and resuspended in phosphate buffered saline (1 × PBS). After induction, the cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded and the cells were resuspended in 1 × PBS buffer. E coli cells were incubated for 60 min with lysozyme (100 μg/mL). After addition of 1% v/v Sarcosyl at 4°C, the cells were lysed by extensive sonication. The sample was centrifuged 8,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C and 2% v/v Triton was added to the supernatant containing the soluble protein fraction. His-tagged PbMLSr was purified using the Ni-NTA Spin Kit (Qiagen Inc., Germantown, MD) and the tags were subsequently removed by the addition of EKMax™ Enterokinase (GIBCO™, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Antibody production

The purified PbMLSr was used to produce anti-PbMLSr polyclonal antibodies in New Zealand rabbits. The immunization protocol consisted of an initial injection of 300 μg of purified recombinant protein in complete Freund's adjuvant and two subsequent injections of the same amount of the antigen in incomplete Freund's adjuvant. Each immunization was followed by an interval of 14 days. After the fourth immunization, the serum containing the anti-PbMLSr polyclonal antibody was collected and stored at -20°C.

Western blotting analysis

SDS-PAGE was performed in 12% polyacrylamide gels according to Laemmli [49]. The proteins were electrophoresed and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue or transferred to a nylon membrane and checked with Ponceau S to determine equal loading. PbMLS, as well as PbMLSr, were detected with the polyclonal antibody raised against the recombinant protein (diluted 1: 4000). After reaction with alkaline phosphatase anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) or alkaline phosphatase anti-human IgG, the reaction was developed with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate-nitroblue tetrazolium (BCIP-NBT).

Cell wall protein extractions

Yeast cells were frozen in liquid nitrogen and disrupted using a mortar and pestle. The procedure was carried out until complete cell rupture, verified by microscopic analysis, and by the failure of cells to grow on Fava Netto's medium. Ground material was lyophilized and resuspended in 25 μL Tris buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8) for each milligram of dry weight, as previously described [50]. The supernatant was separated from the cell wall fraction by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The crude extract was kept and a new protein extraction was performed with the Tris buffer as described above. The cell wall was extensively washed in solutions with decreasing concentrations of 1 M NaCl to remove any extracellular or cytosolic protein contaminants that could adhere to the walls through electrostatic forces. Isolated cell walls were treated with SDS-extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 2% w/v SDS, 100 mM Na-EDTA, and 40 mM β-mercaptoethanol) to extract cell surface-associated proteins, i.e. proteins loosely associated with the cell surface through non-covalent interactions or disulfide bridges (SDS-SW). The proteins from the cell wall and from crude extract were quantified according to Bradford [51].

Preparation of culture filtrate proteins

The culture filtrate were processed as described previously [52], with modifications. Briefly, after 24 and 36 h, and 7 and 14 days of growth at 37°C with gentle agitation, the culture supernatant were removed from the cells by filtration and the culture filtrate was dialyzed and dried by lyophilization. The protein content of the concentrated culture filtrate was quantified according to Bradford [51].

Preparation of Peroxisomal Fraction

The Peroxisome Isolation Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) was used in the preparation of crude peroxisomal fraction from cell cultures P. brasiliensis Pb01 (~2 × 108 cells) by differential centrifugation followed by density gradient centrifugation. Briefly, spheroplasts were obtained at 30°C by lysing the cell wall in 400 U of lyticase (Sigma) for 24 h. Spheroplast membranes were disrupted using a grinder and pestle. After centrifugation for 10 min, the crude peroxisomal fraction was obtained. The organelles were isolated by density gradient centrifugation to separate the enriched peroxisomes fraction from the purified mitochondrial fraction using the Peroxisome Isolation Kit.

The presence of peroxisomes was determined by measuring the activity of the peroxisomal enzyme marker catalase (Catalase Assay Kit) (Sigma-Aldrich). Separation of peroxisomes from mitochondria was determined by measuring the activity of the mitochondrial enzyme marker, cytochrome c oxidase (Cytochrome c Oxidase Assay Kit) (Sigma-Aldrich). In addition, peroxisomal membrane proteins were detected and their degree of enrichment in the purified fraction was determined by immunoblot using anti-PbMLSr.

Affinity ligand assays

Far-Western blot assays were carried out as previously described [53]. PbMLSr underwent SDS-PAGE and was blotted onto nylon membrane. Blotted protein was assayed for laminin, fibronectin, type I and type IV collagen, or for PCM patients' sera as follows. After being blocked for 4 h with 1.5% (w/v) BSA in 10 mM PBS-milk and then washed three times (for 10 min each time) in 10 mM PBS-T, the membranes were incubated with laminin (20 μg/mL), fibronectin (20 μg/mL), or type I and IVcollagen (30 μg/mL), diluted in PBS-T with 2% BSA for 90 min, and then washed three times (for 10 min each time) in PBS-T. The membranes were incubated for 18 h with rabbit anti-laminin, anti-fibronectin, anti-type I collagen or anti-type IV collagen antibodies in PBS-T with 2% BSA (diluted 1:100). The blots were washed with PBS-T and incubated with peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (diluted 1:1000). The blots were washed with PBS-T and the reactive signals were developed with hydrogen peroxide and diaminobenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich) as the chromogenic reagent. The positive control was obtained by incubating the PbMLSr with the polyclonal anti-PbMLSr antibody (diluted 1:500), and the reaction was developed as described above.

ELISA analysis

ELISA was carried out as previously described by Mendes-Giannini et al. [8] with modifications. Briefly, Polypropylene 96-well microtiter ELISA plates were sensitized with extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins (10 μg/mL), overnight at 4°C. After blocking with 2% w/v BSA, 10% v/v SFB and 1% w/v milk, the incubation was followed with PbMLSr (5 μg/mL) for 2 h at 37°C in triplicate wells. The reaction was developed using buffer citrate pH 4.9 conjugated with o-phenylenediamine as chromogenic substrate. Negative controls were performed using PbMLSr or ECM only. Positive controls were performed using anti-PbMLSr, anti-laminin, anti-fibronectin, anti-colagen I or anti-colagen IV antibody. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm and the results were analyzed by using Software Microcal ™Origin ™ software version 5.0 Copyright© [54].

Inhibition assay of P. brasiliensis interaction with epithelial cells using PbMLSr and anti-PbMLSr antibody

A549 pneumocytes were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with PbMLSr (50 μg/mL), diluted in 10 mM PBS. After this incubation period, the cells were washed three times in PBS and 106 yeast forms of P. brasiliensis were added. Incubation was performed for 2 and 5 h at 37°C to allow invasion and internalization, respectively, as described previously [9,15,13]. Four control experiments were performed using A549 cells not preincubated with PbMLSr; P. brasiliensis yeast cells not preincubated with the anti-PbMLSr antibody; pneumocytes preincubated with BSA (25 μg/mL) and P. brasiliensis yeast cells preincubated with rabbit pre-immune serum. The percentage of infected cells was obtained by flow cytometry (BD FACSCanto) (BD Biosciences, Hialeah, FL). An adhesion index was created by multiplying the mean number of attached yeast cells per pneumocyte by the percentage of infected cells. The infection index (adherence plus internalization) was determined by the number of total fungi interacting with the epithelial cells 5 h after addition of the yeast cells, as previously described [15,13]. The mean and S.D. of at least three independent experiments were determined. Statistical analysis was calculated by using ANOVA (F test followed by Duncan test). P values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant.

Biotinylation of protein

PbMLSr was biotinylated with the ECL protein biotinylation kit (GE Healthcare, Amersham Biosciences) as recommended by the manufacturer. Monolayers of A549 cells were incubated with the biotinylated proteins at 37°C overnight and washed with PBS to remove unbound protein. Next, double-distilled water was added and the cells were incubated for 4 h at 25°C to obtain total lysis. The lysates were centrifuged at 1,400 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant underwent electrophoresis by SDS-PAGE. Proteins in the gel were blotted onto a nylon membrane; membrane strips were incubated with blocking buffer for 4 h at 25°C. Incubation for 1 h with streptavidin-HRP followed. A control containing PbMLSr was revealed with the Catalyzed Signal Amplification (CSA) System kit (DAKO). The negative control was developed with the supernatant of A549 cells after lyses (without incubation with the biotinylated protein).

Confocal analysis

The cellular localization of the PbMLS was performed as described by Batista et al. [55] and Lenzi et al. [56] for confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). Briefly, the cells growing in different sources of carbon were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h, washed and centrifuged. After permeabilization with Triton X-100, the cells were washed in PBS and incubated in blocking solution (2.5% BSA, 1% skim milk, 8% fetal calf serum) for 20 min (Fernandes da Silva, 1988). The diluted (1:100) primary antibody anti-PbMLSr was added overnight at 4°C. After washing three times with PBS, the cells were incubated with secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488 anti-rabbit Molecular Probes 1:700) for 1 hour. Before mounting in 90% glycerol in PBS, adjusted to pH 8.5, containing antifading agent (p-phenylenediamine 1 g/L) (Sigma-Aldrich), the cells were stained with Evans blue (1/10000 in 0.01 M PBS). The specimens were analyzed by laser confocal microscopy (LSM 510-META, Zeiss).

Flow cytometry assay analysis

All flow cytometry analyses were performed on a BD FACSCanto (BD Biosciences) using an air-cooled argon-ion laser tuned to 488 nm and 115 mW. The flow rate was kept at approximately 10,000 events (cells), and green fluorescence was amplified logarithmically. Ten thousand events were collected as monoparametric histograms of log fluorescence, as well as list mode data files. The data were analyzed by FACSDiva Software (BD Biosciences) and Origin Software [54].

Enzymatic activity

MLS activity was determined as described by Zambuzzi-Carvalho (2009) [30]. Briefly, the enzymatic assay was carried out at room temperature. 25 mg samples were added to 500 ml assay buffer containing 5 mM acetyl-CoA (20 ml) and water to a volume of 980 ml. The reaction had the optical densities read at 232 nm until stabilization. The enzymatic reaction was started by the addition of 100 mM glyoxylate (20 ml). The method is based on the consumption of acetyl-CoA at 232 nm. The activity was calculated considering that one unit at 232 nm is defined as 222 nmols/mg of acetyl-CoA. The specific activities were given in U/mg protein, with U being equal at nmol/min.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± SD of the mean of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA (F-test followed by Duncan test). P-values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant.

Authors' contributions

BRSN carried out all assays. JFS and MJSMG participated in the adhesion and infection assays. HLL participated in confocal assays. BRSN, MJSMG, HLL, CMAS and MP contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. MP conceived, designed and coordinated the study. All authors contributed to the discussion of results. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Benedito Rodrigues da Silva Neto, Email: bio.neto@gmail.com.

Julhiany de Fátima da Silva, Email: julhiany.silva@gmail.com.

Maria José Soares Mendes-Giannini, Email: gianninimj@gmail.com.

Henrique Leonel Lenzi, Email: henrique.lenzi@gmail.com.

Célia Maria de Almeida Soares, Email: celia@icb.ufg.br.

Maristela Pereira, Email: mani@icb.ufg.br.

Acknowledgements

This study at the Universidade Federal de Goiás was supported by grants from the Ministério de Ciência e Tecnologia (MCT), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos (FINEP), and by the International Foundation for Science (IFS), Stockholm, Sweden, through a grant to M.P.. B.R.S.N. was supported by a fellowship from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Ensino Superior (CAPES).

References

- Rippon JW. Dimorphism in pathogenic fungi. Crit Ver Microbiol. 1980;8:49–97. doi: 10.3109/10408418009085078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummer E, Castaneda E, Restrepo A. Paracoccidioidomycosis: an update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:89–117. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.2.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pina A, Bernadino S, Calich VLG. Alveolar macrophages from susceptible mice are more competent than those of resistant mice to control initial Paracoccidioides brasiliensis infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1088–1099. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1107738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tart RC, Van IR. Identification of the surface component of Streptococcus defectivus that mediates extracellular matrix adherence. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4994–5000. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.4994-5000.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Palecek SP. Distinct domains of the Candida albicans adhesin Eap1p mediate cell-cell and cell-substrate interactions. Microbiol. 2008;154:1193–1203. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/013789-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon JP, Wheat J, Sobel ME, Pasula R, Downing JF, Martin WJ. Laminin Binds to Histoplasma capsulatum A Possible Mechanism of Dissemination. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1010–1017. doi: 10.1172/JCI118086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris S, Boisvieux-Ulrich E, Crestani B, Houcine O, Taramelli D, Lombardi L, Latgé JP. Internalization of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia by epithelial and endothelial cells. Infec Immun. 1997;4:1510–1514. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1510-1514.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes-Giannini MJ, Andreotti PF, Vincenzi LR, Monteiro Da Silva JL, Lenzi HL, Benard G, Zancope- Oliveira R, De Matos Guedes HL, Soares CP. Binding of extracellular matrix proteins to Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. Microb Infect. 2006;8:1550–9. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti PF, Monteiro Da Silva JL, Bailão AM, Soares CM, Benard G, Soares CP, Mendes- Giannini MJ. Isolation and partial characterization of a 30 kDa adhesin from Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. Microb Infect. 2005;7:875–81. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicentini AP, Gesztesi JL, Franco MF, De Souza W, De Moraes JZ, Travassos LR. Binding of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis to laminin through surface glycoprotein gp43 leads to enhancement of fungal pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1465–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1465-1469.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dranginis AM, Rauceo JM, Coronado JE, Lipke PN. A biochemical guide to yeast adhesins: glycoproteins for social and antisocial occasions. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71:282–94. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00037-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A, Lenzi HL, Motta EM, Caputo L, Sahaza JH, Cock AM, Ruiz AC, Restrepo A, Cano LE. Expression of adhesion molecules in lungs of mice infected with Paracoccidioides brasiliensis conidia. Microb Infect. 2005;7:666–73. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna SA, Monteiro da Silva JL, Mendes-Giannini MJ. Adherence and intracellular parasitism of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in Vero cells. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:877–84. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)00390-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes-Giannini MJS, Taylor ML, Bouchara JB, Burger E, Calich VLG, Escalante ED. Pathogenesis II: fungal responses to host responses: interaction of host cells with fungi. Med Mycol. 2000;38:113–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes-Giannini MJ, Hanna SA, da Silva JL, Andreotti PF, Vincenzi LR, Benard G, Lenzi HL, Soares CP. Invasion of epithelial mammalian cells by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis leads to cytoskeletal rearrangement and apoptosis of the host cell. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:882–891. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa MS, Bao SN, Andreotti PF, de Faria FP, Felipe MS, dos Santos Feitosa L, Mendes-Giannini MJ, Soares CM. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis is a cell surface protein, involved in fungal adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins and interaction with cells. Infect Immun. 2006;74:382–389. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.382-389.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira LA, Báo SN, Barbosa MS, da Silva JL, Felipe MS, Santana JM, Mendes-Giannini MJ, de Almeida Soares CM. Analysis of the Paracoccidioides brasiliensis Triosephosphate Isomerase suggests the potential for adhesin function. FEMS Yeast Res. 2007;7:1381–1388. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2007.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancholi V, Chhatwal GS. Housekeeping enzymes as virulence factors for pathogens. Int J Med. 2003;293:391–401. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling E, Feldman G, Portnoi M, Dagan R, Overweg K, Mulholland F, Chalifa-Caspi V, Wells J, Mizrachi-Nebenzahl Y. Glycolytic enzymes associated with the cell surface of Streptococcus pneumoniae are antigenic in humans and elicit protective immune responses in the mouse. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;138:290–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinhikar AG, Vargas D, Li H, Mahaffey SB, Hinds L, Belisle JT, Laal S. Mycobacterium tuberculosis malate synthase is a laminin-binding adhesin. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:999–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivas I, Royuela M, Romero B, Monteiro MC, Mínguez JM, Laborda F, De Lucas JR. Ability to grow on lipids accounts for the fully virulent phenotype in neutropenic mice of Aspergillus fumigatus null mutants in the key glyoxylate cycle enzymes. Fungal Genet Biol. 2007;45:45–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rude TH, Toffaletti DL, Cox G, Perfect JR. Relatioship of the glyoxylate pathway to the pathogenesis of Cryptococcus neoformas. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5684–5694. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5684-5694.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz MC, Fink GR. The glyoxylate cycle is required for fungal virulence. Nature. 2001;412:83–86. doi: 10.1038/35083594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz MC, Fink GR. Life and death in a macrophage: Role oh the glyoxylate cycle in virulence. Eukaryot Cell. 2002;1:657–662. doi: 10.1128/EC.1.5.657-662.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney JD, Höner zu Bentrup K, Muñoz-Elías EJ, Miczak A, Chen B, Chan WT, Swenson D, Sacchettini JC, Jacobs WR Jr, Russell DG. Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and mice requires the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase. Nature. 2000;406:735–8. doi: 10.1038/35021074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Elías EJ, McKinney JD. Mycobacterium tuberculosis isocitrate lyases 1 and 2 are jointly required for in vivo growth and virulence. Nat Med. 2005;11:638–44. doi: 10.1038/nm1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould TA, Langemheen H van de, Muñoz-Elías EJ, McKinney JD, Sacchettini JC. Dual role of isocitrate lyase 1 in the glyoxylate and methylcitrate cycles in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:940–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZX, Brämer CO, Steinbüchel A. The glyoxylate bypass of Ralstonia eutropha. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;228:63–71. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00722-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon PS, Lee RC, Greer Wilson TJ, Oliver RP. Pathogenicity of Stagonospora nodorum requires malate synthase. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:1065–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambuzzi-Carvalho PF, Cruz AHS, Santos-Silva LK, Goes AM, Soares CM, Pereira M. The malate synthase of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis is required in the glyoxylate cycle and in the allantoin degradation pathway. Med Mycol. 2009;4:1–12. doi: 10.1080/13693780802609620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould SJ, Keller GA, Subramani S. Identification of a peroxisomal targeting signal at the carboxy terminus of firefly luciferase. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2923–2931. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laal S, Samanich KM, Sonnenberg MG, Zolla-Pazner S, Phadtare JM, Belisle JT. Human humoral responses to antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: immunodominance of high-molecular-mass antigens. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:49–56. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.1.49-56.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg MG, Belisle JT. Definition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture filtrate proteins by two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, Nterminal amino acid sequencing and electrospray mass spectrometry. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4515–4524. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4515-4524.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanich K, Belisle JT, Laal S. Homogeneity of antibody responses in tuberculosis patients. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4600–4609. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4600-4609.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes-Giannini MJ, Monteiro da Silva JL, de Fátima da Silva J, Donofrio FC, Miranda ET, Andreotti PF, Soares CP. Interactions of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis with host cells: recent advances. Mycopathologia. 2008;165:237–248. doi: 10.1007/s11046-007-9074-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhatwal GS. Anchorless adhesins and invasins of Gram-positive bacteria: a new class of virulence factors. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:205–8. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(02)02351-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann S, Rohde M, Chhatwal GS, Hammerschmidt S. Alpha-enolase of Streptococcus pneumoniae is a plasmin (ogen)-binding protein displayed on the bacterial cell surface. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:1273–1287. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallo SF, Kannan TR, Blaylock MW, Baseman JB. Elongation factor Tu and E1 beta subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex act as fibronectin binding proteins in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:1041–1051. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennermalm A, Li YH, Bohaufs L, Jarstrand C, Brauner A, Brennan FR, Flock JI. Antibodies against a truncated Staphylococcus aureus fibronectinbinding protein protect against dissemination of infection in the rat. Vaccine. 2001;19:3376–3383. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofek I, Hasty DL, Sharon N. Anti-adhesion therapy of bacterial diseases: prospects and problems. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;38:181–191. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal Pessolani MC, Marques MA, Reddy VM, Locht C, Menozzi FD. Systemic dissemination in tuberculosis and leprosy: do mycobacterial adhesins play a role? Microbes Infect. 2003;5:677–684. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(03)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho HM, Teel LD, Kokai-Kun JF, O'Brien AD. Antibody against the carboxyl terminus of intimin alpha reduces enteropathogenic Escherichia coli adherence to tissue culture cells and subsequent induction of actin polymerization. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2541–2546. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2541-2546.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A, Reljic R, Naylor I, Clark SO, Falero-Diaz G, Singh M, Challacombe S, Marsh PD, Ivanyi J. Passive protection with immunoglobulin A antibodies against tuberculous early infection of the lungs. Immunology. 2004;111:328–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01809.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felipe MS, Andrade RV, Arraes FB, Nicola AM, Maranhão AQ, Torres FA, Silva-Pereira I, Poças-Fonseca MJ, Campos EG, Moraes LM, Andrade PA, Tavares AH, Silva SS, Kyaw CM, Souza DP, Pereira M, Jesuíno RS, Andrade EV, Parente JA, Oliveira GS, Barbosa MS, Martins NF, Fachin AL, Cardoso RS, Passos GA, Almeida NF, Walter ME, Soares CM, Carvalho MJ, Brígido MM. PbGenome Network. Transcriptional profiles of the human pathogenic fungus Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in mycelium and yeast cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24706–24714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman GH, dos Reis Marques E, Duarte Ribeiro DC, de Souza Bernardes LA, Quiapin AC, Vitorelli PM, Savoldi M, Semighini CP, de Oliveira RC, Nunes LR, Travassos LR, Puccia R, Batista WL, Ferreira LE, Moreira JC, Bogossian AP, Tekaia F, Nobrega MP, Nobrega FG, Goldman MH. Expressed sequence tag analysis of the human pathogen Paracoccidioides brasiliensis yeast phase: identification of putative homologues of Candida albicans virulence and pathogenicity genes. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2:34–48. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.1.34-48.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro JP, Clemons KV, Mirels LF, Coller JA, Wu TD, Shankar J, Lopes CR, Stevens DA. Genomic DNA microarray comparison of gene expression patterns in Paracoccidioides brasiliensis mycelia and yeasts in vitro. Microbiology. 2009;155:2795–808. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.027441-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos KP, Bailão AM, Borges CL, Faria FP, Felipe MS, Silva MG, Martins WS, Fiúza RB, Pereira M, Soares CM. The transcriptome analysis of early morphogenesis in Paracoccidioides brasiliensis mycelium reveals novel and induced genes potentially associated to the dimorphic process. BMC Microbiol. 2007;10:7–29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian S, Kim S-J, Podila GP. Differential expression of malate synthase gene during the preinfection stage of symbiosis in the ectomycorrhizal fungus Laccaria bicolor. New Phytol. 2002;154:517–527. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;2227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damveld RA, Arentshorst M, VanKuyk PA, Klis FM, Hondel CA van den, Ram AF. Characterization of CwpA, a putative glycosylphosphatidylinositolanchored cell wall mannoprotein in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus niger. Fungal Genet Biol. 2005;42:873–885. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A dye binding assay for protein. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh KK, Dong Y, Belisle JT, Harder J, Arora VK, Laal S. Antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis recognized by antibodies during incipient, subclinical tuberculosis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:354–358. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.2.354-358.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guichet A, Copeland JW, Erdelyi M, Hlousek D, Zavorszky P, Ho J, Brown S, Percival-Smith A, Krause HM, Ephrussi A. The nuclear receptor homologue Ftz-F1 and the homeodomain protein Ftz are mutually dependent cofactors. Nature. 1997;385:548–552. doi: 10.1038/385548a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MICROCAL ITC Data Analysis in OriginR. Tutorial Guide. 5.0; MicroCal. 1998. http://www.microcalorimetry.com

- Batista WL, Matsuo AL, Ganiko L, Barros TF, Veiga TR, Freymüller E, Puccia R. The PbMDJ1 gene belongs to a conserved MDJ1/LON locus in thermodimorphic pathogenic fungi and encodes a heat shock protein that localizes to both the mitochondria and cell wall of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:379–390. doi: 10.1128/EC.5.2.379-390.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzi HL, Pelajo-Machado M, Vale BS, Panasco MS. Microscopia de Varredura Laser Confocal: Princípios e Aplicações Biomédicas. Newslab. 1996;16:62–71. [Google Scholar]