Abstract

Background

Evidence suggests that brief interventions in the trauma care setting reduce drinking, subsequent injury and DUI arrest. However, evidence on the effectiveness of these interventions in ethnic minority groups is lacking. The current study evaluates the efficacy of brief intervention among Whites, Blacks and Hispanics in the U.S.

Methods

We conducted a two-group parallel randomized trial comparing Brief Motivational Intervention (BMI) and Treatment as Usual with assessment (TAU+) to evaluate treatment differences in drinking patterns by ethnicity. Patients were recruited from a Level 1 urban trauma center over a two year period. The study included 1493 trauma patients including 668 Whites, 288 Blacks, and 537 Hispanics. Hierarchical linear modeling was used to evaluate ethnic differences in drinking outcomes including volume per week, maximum amount consumed in one day, percent days abstinent and percent days heavy drinking at 6 and 12 month follow up. Analyses controlled for age, gender, employment status, marital status, prior alcohol treatment, type of injury and injury severity. Special emphasis was given to potential ethnic differences by testing the interaction between ethnicity and BMI.

Results

At 6 and 12 month follow up, BMI significantly reduced maximum amount consumed in one day (p<.001; p<.001, respectively) and percent days heavy drinking (p<.05; p<.05, respectively) among Hispanics. Hispanics in the BMI group also reduced average volume per week at 12 month follow up (X2=6.8, df=1, p<.01). In addition, Hispanics in TAU+ reduced maximum amount consumed at 6 and 12 month follow up (p<.001; p<.001) and volume per week at 12 month follow up (p<.001). Whites and Blacks in both BMI and TAU+ reduced volume per week and percent days heavy drinking at 12 month follow up (p<.001; p<.01, respectively) and decreased maximum amount at 6 (p<.001) and 12 month follow up (p<.001). All three ethnic groups In both BMI and TAU+ reduced volume per week at 6 month follow up (p<.001) and percent days abstinent at 6 (p<.001) and 12 month follow up (p<.001).

Conclusions

All three ethnic groups evidenced reductions in drinking at 6 and 12 month follow up independent of treatment assignment. Among Hispanics, BMI significantly reduced alcohol intake as measured by average volume per week, percent days heavy drinking and maximum amount consumed in one day.

Introduction

There is substantial evidence that brief intervention in the trauma care setting reduces drinking and risk of future injury.1–5 For example, Schermer et al. found that rates of arrest for DUI three years after admission for an alcohol related injury were cut in half with a brief intervention.2 For every 9 interventions provided, one DUI arrest was prevented. Moreover, these interventions confer $3.81 in cost savings for every dollar spent. 3 Thus, brief interventions in the trauma care setting have individual, organizational and social benefits. However, prior studies in the United States have been conducted with predominately Caucasian samples and have neglected the influence of ethnicity on drinking outcomes.

In general population surveys conducted in the United States, patterns of alcohol consumption have been found to vary across ethnic groups. In comparison to White men, Black and Hispanic males who drink more frequently engage in heavy drinking.6 Hispanic and Black males have longer careers of heavy drinking than their White male counterparts, even if they begin drinking later in life.7 Moreover, for any given level of consumption, ethnic minority populations experience more negative health and social consequences of drinking than Whites.8 For example, among drinkers, Black and Hispanic males in comparison to White males have higher rates of experiencing three or more alcohol problems.6, 9 While differences in socioeconomic status and health insurance coverage across ethnic groups may impact treatment utilization, Blacks and Hispanics with alcohol abuse or dependence are significantly less likely than comparable Whites to receive formal treatment.10–12 When they do seek treatment, ethnic minorities often present with characteristics that tend to be associated with lower rates of success (e.g., lower income, less education, more extensive family histories of alcoholism, poorer physical health, greater unemployment and legal problems) compared with Whites.13, 14 Despite more complex treatment needs, ethnic minorities are less likely to receive specialty treatment or multiple episodes of care.13 As a result of these observed trends, it was hypothesized that ethnic minorities would be less likely to respond to brief intervention as they would tend to require more intensive intervention or treatment.

In this clinical trial, Blacks, Whites and Hispanics were randomly assigned to Treatment As Usual with assessment (TAU+) or assessment plus Brief Motivational Intervention (BMI). The primary aim of this study was to evaluate potential ethnic differences in drinking outcomes following brief intervention in the trauma care setting. The primary drinking outcomes of interest were volume per week, maximum number of standard drinks consumed in one day, typical quantity consumed, percent days abstinent and percent days heavy drinking. It was hypothesized that that brief intervention would be less effective in reducing drinking among Blacks and Hispanics.

Methods

Study Recruitment

Patients were recruited from an urban Level I trauma center between May, 2003 and May, 2005. All enrolled participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. Subjects were compensated $25 for the baseline assessment and $50 for the six and twelve month follow up assessments. The study procedures were approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and the Institutional Review Board of the hospital where data were collected. In addition, a certificate of confidentiality was obtained from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Screening and Enrollment

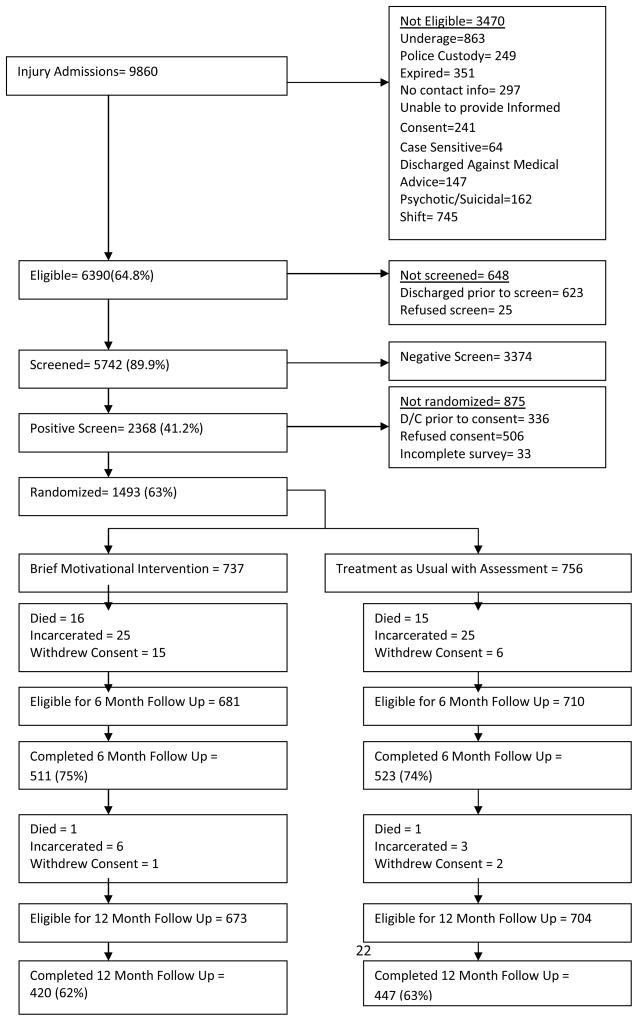

Study recruitment and follow up rates are presented in Figure 1. Sampling was limited to injured patients who identified themselves as Black, White or Hispanic. Injury was defined as an intentional or unintentional event caused by an external factor, even if a medical condition was a causal factor. The final sample of patients randomized to TAU+ or BI consisted of 668 Whites (45%), 537 Hispanics (36%) and 288 Blacks (19%). Forty seven percent (n=253) of the Hispanic population identified Spanish as their primary language were interviewed by a bilingual clinician.

Figure 1.

Study Recruitment

Patients were excluded from participation if they were1) less than 18 years of age 2) spoke neither English nor Spanish 2) they had no identifiable residence 3) were under arrest or in police custody at the time of admission or during their hospital stay 4) were judged by the trauma care or research staff to be actively suicidal or psychotic 5) were victims of sexual assault or 6) had a medical condition that precluded a face-to-face interview. Patients who were intoxicated at the time of their injury or presented with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) ≤ 14 were monitored by research staff for inclusion in the study. Patients with a GCS ≤ 14 that did not resolve prior to discharge were not eligible for screening or enrollment. As a prerequisite for recruitment, all patients had to demonstrate orientation to person, place and time. Injured patients were eligible for participation in the study following medical stabilization and prior to discharge from the hospital regardless of the patient’s length of stay.

Patient recruitment was limited to Thursday through Monday from 9 am to 6 pm. Prior studies suggested that these hours were the most efficient times to screen and enroll patients. 15, 16 To minimize the impact of screening procedures on medical care, a sequential screening process was employed. e.g., subsequent screening procedures were only implemented if the patient screened negative on prior screening criteria. Screening consisted of four sequential criteria: 1) Clinical indication of acute intoxication or alcohol use or positive BAC; 2) self reported drinking 6 hours prior to injury; 3) at risk drinking per NIAAA guidelines (e.g., 7 drinks/week women, 14 drinks/week men; more than 4 drinks/day in men; more than 3 drinks/day in women or 4) positive on one or more items of the CAGE. 17, 18, 19 Trauma center staff in collaboration with study clinicians attempted to screen all eligible trauma activations during the study period.

Assessment

Drinking outcomes which were assessed as follows

Alcohol Use

Quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption was determined at baseline, six and twelve month follow up using a graduated frequency.22, 23 One standard drink was defined as 12 ounces of beer, 5 ounces of wine, or 1.5 ounces of hard liquor.24 Weekly alcohol volume was calculated using the basic quantity/frequency approach by multiplying usual quantity of drinks per occasion by frequency of drinking.24 In addition, the maximum amount consumed in one day was collected. At six and twelve month follow up, percent days abstinent was estimated using frequency of drinking. Percent days heavy drinking was calculated by dividing the frequency of drinking five or more per occasion by the frequency of drinking.

Treatment as Usual with Assessment (TAU+) and Assessment with Brief Motivational Intervention (BMI)

Patients were randomized to either treatment as usual with assessment (TAU+) or an assessment with Brief Motivational Intervention (BMI) using a permuted block design (block size 6) to ensure approximately equal distribution of patients according to their race/ethnicity. To reduce interviewer bias, study clinicians were blinded to patient randomization prior to completion of the baseline assessment. All patients, regardless of treatment assignment received information regarding hospital and community services relevant to the injured patient. This information included, but was not limited to, substance abuse treatment and self help groups and the availability of drug and alcohol counselors. Information pertaining to hospital and community resources relevant to the care of injured patients was also provided. All patients were also provided handouts regarding the effects of alcohol, defition of at risk drinking and strategies to quite or cut down.

Treatment as Usual with Assessment (TAU+)

Following the initial assessment, all patients assigned to TAU+ were provided patient handouts. This was consistent with general practice for treating patients with alcohol problems at the Level 1 trauma center at the time the clinical trial was conducted.

Brief Motivational Intervention (BMI)

Brief Motivational Intervention (BMI) with injured patients has been described elsewhere.25, 26 In short, the primary components consist of acknowledging the patients responsibility for changing drinking, encouraging the patient to explore pros and cons of drinking, assessing importance, confidence and readiness to change drinking behavior, reinforcing patient’s sense of self-efficacy, and providing support for any efforts or intention to quit drinking or reduce harm associated with drinking including injury. Information pertaining to alcohol use and treatment resources was provided upon request by the patient or was provided upon patient request or with their permission (i.e., in a manner consistent with the principles of motivational interviewing).

Training and Supervision

Clinicians were master’s level or degreed and were certified in brief intervention following the successful completion of training. Trainings consisted of a mix of didactic lectures, video examples and role play. Successful completion of the certification process required submission of three audio taped interventions with clients which exceeded threshold proficiency as indicated by coding on the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code v1.0. Following training three procedures were used to monitor clinician performance including group supervision, coaching using direct observation and audio recording of interventions. Ten percent of interventions were randomly selected to be audio taped. Clinicians were required to submit an audio tape at least once per month. In all, 113 of the 736 intervention were taped and coded using the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code v1.0. The mean of the Global Therapist Rating (M=5.8, SE=.08), Reflection to Question Ratio (M=1.6, SE=.13), Percent Open Questions (M=.55, SE=..02), Percent Complex Reflections (M=.41, SE=..02) and Percent MI Consistent (M=.97, SE=1.3) behaviors counts were determined from the MISC ratings. With the exception of the percent of complex reflections in which some audio tapes were below threshold proficiency (>40%), the means and 95% CI indicated that therapist behaviors were at or above the threshold or expert proficiency levels.

Follow Up Assessment

Research staff blind to treatment assignment conducted follow up assessments by telephone at six and 12 months. Of the patients eligible for follow up, 1062 (77%) completed a six month assessment and 907 (66%) completed a 12 month assessment. Hispanics (OR=.59, 95% CI=.43–.83) were less likely to complete 6 month follow up. There were no significant predictors of loss to follow up at 12 months.

Statistical Analysis

Longitudinal analyses were conducted using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) of drinking outcomes with random effects for subject and time within subject using HLM version 6.04.27, 28 The primary outcomes of interest in this study were volume per week, maximum amount consumed in one day, percent days abstinent and percent days heavy drinking. Volume per week and maximum amount per occasion were log transformed. Analyses controlled for age, gender, employment status, marital status, education, prior alcohol treatment, type of injury and injury severity.

In longitudinal analysis, outcomes are often modeled as linearly related to time (e.g. Raudenbush and Bryk Chapter 6).27 In the current study, inspection of the data revealed generally large differences between baseline and 6-month levels and much smaller differences between 6 and 12 months. Therefore we treated time as categorical and represented 6 months and 12 months as dummy variables, relative to baseline as the reference category.29, 30

We fit one model for each outcome, for a total of four analyses. Within each analysis, we assessed potential modification effect of ethnicity on treatment (treatment by ethnicity interaction). Because these interaction effects were anticipated a priori, we modeled effects of treatment as possibly different for each ethnic group. A chi-square statistic provided a test of each null hypothesis that the effect in question was equal to zero. When no significant treatment effects were observed, changes in drinking outcomes across time were examined, pooling across treatment and ethnic groups which did not differ significantly. When treatment effects were observed, similar tests for changes in drinking outcomes across time were conducted for TAU+. The effect size and magnitude of change are reported when applicable. The observed effect sizes were calculated by dividing the difference between the observed mean changes for TAU+ and BMI by the pooled standard deviation.31 Effect sizes ranged from small (approximately d=.20) to medium (d=.50).32

Results

Table 1 shows demographic and other relevant characteristics for Whites, Blacks and Hispanics in the BMI and TAU+ intervention groups. Chi-square tests were conducted within ethnic groups to compare patients assigned to TAU+ and BMI in terms of age, gender, marital status, education, employment status, income, type of injury. T test were conducted within ethnic groups to compare patients assigned to TAU+ and BMI in terms of frequency of five or more standard drinks per occasion, average number of standard drinks consumed per week and maximum number of standard drinks in one day, alcohol abuse or dependence and drug use or dependence. Whites in the TAU+ group were less likely to be male (p<.01), less likely to report their income (p<.05) and had fewer drinks the day of their heaviest drinking occasion (p<.05). Blacks assigned to TAU+ group were more likely to be female (p<.05). Hispanics assigned TAU+ had significantly fewer percent days heavy drinking (p<.05). In addition, differences in demographic characteristics and baseline drinking patterns were tested using a chi-square or one-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc comparisons. In terms of demographic characteristics, Hispanics were younger [F=67.2 (2,1490), p<.01; Tukey HSD <.01] and more likely to have less than a high school education (X2 = 2.8, p<.01), to be male (X2=21.5, p<.01) and to be employed (X2=47.9, p<.01) than either Blacks or Whites. In comparison to Whites and Blacks, Hispanics had a greater percent days abstinent [F=18.1 (2,1490), p<.01; Tukey HSD <.01] and heavy drinking [F=29.5 (2,1490), p<.01; Tukey HSD <.01]. Whites were less likely to be single (X2=79.9, p<.01) and had higher incomes (X2=1.8, p<.01) than Blacks and Hispanics. Finally, Blacks consumed less on one occasion than Whites and Hispanics [F=67.2 (2,1490), p<.01; Tukey HSD <.01].

Table 1.

Demographic, injury-related, and drinking characteristics of study participants by intervention group and race/ethnicity

| Whites | Blacks | Hispanics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAU+ (n=342) | BMI (n=326) | TAU+ (n=140) | BMI (n=148) | TAU+ (n=274) | BMI (n=263) | |

| Age category % | ||||||

| 18–24 | 29 | 24 | 13 | 23 | 40 | 39 |

| 25–34 | 25 | 27 | 24 | 19 | 36 | 38 |

| 35–44 | 25 | 26 | 30 | 30 | 16 | 17 |

| 45+ | 20 | 24 | 33 | 28 | 08 | 06 |

| Male % | 74* | 83* | 76 | 85 | 88 | 89 |

| Marital Status % | ||||||

| Single, never married | 44 | 41 | 43 | 51 | 49 | 46 |

| Married or living with life time partner | 25 | 28 | 26 | 22 | 32 | 35 |

| Separated, divorced, widowed or married not living with spouse | 30 | 31 | 31 | 27 | 19 | 20 |

| Education level % | ||||||

| More than high school | 39 | 40 | 22 | 20 | 12 | 13 |

| High school diploma | 36 | 38 | 54 | 51 | 21 | 24 |

| Some high school | 25 | 21 | 24 | 28 | 67 | 63 |

| Employment status % | ||||||

| Employed for wages | 70 | 69 | 58 | 50 | 78 | 77 |

| Income level (US$) % | ||||||

| No income | 7 | 2 | 7 | 11 | 6 | 5 |

| ≤ 10,000 | 12 | 11 | 26 | 33 | 23 | 25 |

| 10,000 to ≤ 30,000 | 31 | 37 | 39 | 41 | 52 | 52 |

| 30,000 to ≤ 50,000 | 24 | 22 | 21 | 10 | 12 | 12 |

| > 50,000 | 25 | 27 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 7 |

| % Intentional injuries | 12 | 12 | 33 | 30 | 28 | 27 |

| Volume per Week** | 16.3 (26.7) | 15.7 (24.3) | 14.4 (20.4) | 13.6 (15.5) | 15.4 (28.9) | 16.3 (22.3) |

| Maximum Amount** | 13.0 (8.8)* | 14.8 (11.9)* | 10.1 (8.4) | 9.3 (5.5) | 14.4 (10.1) | 15.4 (11.3) |

| Percent Days Abstinent** | 65% (31%) | 65% (30%) | 61% (33%) | 61%(31%) | 73% (27%) | 73% (27%) |

| Percent Days Heavy Drinking** | 59% (41%) | 55% (42%) | 49% (42%) | 54% (42%) | 67% (39%)* | 76% (37%)* |

significant differences between TAU+ and BMI within ethnic group

mean (standard deviation)

Analyses pertaining to volume per week, maximum amount, percent days abstinent and percent days heavy drinking by ethnicity are reported in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5. First, changes in drinking outcomes week from baseline to six and 12 month follow up for each ethnic group by treatment condition are presented (Tables 2a, 3a, 4a and 5a). Second, the effects of BMI on drinking outcomes by ethnicity are reported (Tables 2b, 3b, 4b and 5b). Third, the results of tests for changes in drinking outcomes across time when no significant treatment effect was observed or for the TAU+ condition when a treatment effect was observed are presented (Tables 2c, 3c, 4c and 5c).

Table 2.

Volume per Week

| a. Changes in Volume Per Week from Baseline to six and 12 month follow up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 Months | 12 Months | |||

| TAU+ | BMI | TAU+ | BMI | |

| Whites | −5.1 (21.7) | −5.0 (26.3) | −3.7 (21.6) | −4.6 (26.6) |

| Blacks | −4.0 (21.8) | −4.5 (18.5) | −3.5 (19.4) | −3.0 (20.3) |

| Hispanics | −8.0 (19.4) | −9.4 (24.2) | −5.7 (17.9) | −8.9 (26.2) |

| b. Effects of BMI on Volume Per Week †, †† | ||||

| b | X2 (p value) | b | X2 (p value) | |

| Whites | .07 | .16 (>.50) | .06 | .09 (>.50) |

| Blacks | .10 | .13 (>.50) | .27 | .90 (>.50) |

| Hispanics | −.37 | 3.03 (.09) | −.59 | 6.8 (.01)* |

| c. Changes in Volume Per Week Across Time | ||||

| X2 | p value | X2 | (p value) | |

| Whites, Blacks and Hispanics in BMI and TAU+* | 141.6 | <.001 | --- | --- |

| Hispanics in TAU+** | --- | --- | 42.1 | <.001 |

| Whites and Blacks in BMI and TAU+* | --- | --- | 26.8 | <.001 |

controlling for age, gender, marital status, employment status, education, prior substance abuse treatment, type of injury, injury severity

log transformed

no significant treatment effect observed

significant treatment effect observed

Table 3.

Maximum Amount

| a. Changes in Maximum Amount from Baseline to 6 and 12 month follow up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 Months | 12 Months | |||

| TAU+ | BMI | TAU+ | BMI | |

| Whites | −4.8 (8.8) | −6.0 (10.6) | −4.8 (8.0) | −6.0 (10.9) |

| Blacks | −3.9 (9.9) | −3.0 (8.3) | −2.8 (10.3) | −2.0 (8.9) |

| Hispanics | −6.2 (10.0) | −9.3 (11.1) | −5.9 (9.6) | −9.1 (11.9) |

| b. Effects of BMI on Maximum Amount †, †† | ||||

| b | X2 (p value) | b | X2 (p value) | |

| Whites | .01 | .02 (>.50) | −.04 | .13 (>.50) |

| Blacks | .05 | .09 (>.50) | .05 | .10 (>.50) |

| Hispanics | −.36 | 8.6 (.004)** | −.46 | 11.9 (.001)** |

| c. Changes in Maximum Amount Across Time | ||||

| X2 | p value | X2 | (p value) | |

| Whites and Blacks in BMI and TAU+* | 107.2 | <.001 | 53.1 | <.001 |

| Hispanics in TAU+** | 86.2 | <.001 | 57.3 | <.001 |

controlling for age, gender, marital status, employment status, education, prior substance abuse treatment, type of injury, injury severity

log transformed

no significant treatment effect observed

significant treatment effect observed

Table 4.

Percent Days Abstinent by ethnicity

| a. Changes in Percent Days Abstinent from Baseline to 6 and 12 month follow up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 Months | 12 Months | |||

| TAU+ | BMI | TAU+ | BMI | |

| Whites | 9% (32%) | 10% (34%) | 5% (31%) | 7% (36%) |

| Blacks | 11% (41%) | 13% (31%) | 8% (36%) | 9% (34%) |

| Hispanics | 10% (26%) | 12% (29%) | 10% (27%) | 12% (30%) |

| b. Effects of BMI on Percent Days Abstinent† | ||||

| b | X2 (p value) | b | X2 (p value) | |

| Whites | .002 | .003 (>.50) | .004 | .02 (>.50) |

| Blacks | −.003 | .005 (>.50) | −.016 | .14 (>.50) |

| Hispanics | .006 | .03 (>.50) | .009 | .07 (>,50) |

| c. Changes in Percent Days Abstinent Across Time | ||||

| X2 | p value | X2 | (p value) | |

| Whites, Blacks and Hispanics in BMI and TAU+* | 44.0 | <.001 | 26.2 | <.001 |

controlling for age, gender, marital status, employment status, education, prior substance abuse treatment, type of injury, injury severity

no significant treatment effect observed

Table 5.

Percent Days Heavy Drinking

| a. Changes in Percent Days Abstinent from Baseline to 6 and 12 month follow up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 Months | 12 Months | |||

| TAU+ | BMI | TAU+ | BMI | |

| Whites | −8% (49%) | −5% (44%) | −17% (47%) | −12% (49%) |

| Blacks | −6% (53%) | −15% (54%) | −3% (54%) | −16% (58%) |

| Hispanics | −6% (55%) | −20% (52%) | −2% (52%) | −17% (49%) |

| b. Effects of BMI on Percent Days Abstinent†† | ||||

| b | X2 (p value) | b | X2 (p value) | |

| Whites | .04 | .62 (>.50) | .06 | 1.5 (.22) |

| Blacks | −.08 | 1.2 (.27) | −.12 | 2.8 (.09) |

| Hispanics | −.11 | 3.8 (.047)* | −.14 | 4.9 (.02)* |

| c. Changes in Percent Days Abstinent Across Time | ||||

| X2 | p value | X2 | (p value) | |

| Whites, Blacks and Hispanics in BMI and TAU+* | 5.0 | .02 | .05 | >.50 |

| Hispanics in TAU+** | 2.2 | .13 | 1.3 | .25 |

controlling for age, gender, marital status, employment status, education, prior substance abuse treatment, type of injury, injury severity

no significant treatment effect is observed

significant treatment effect observed

Volume per Week

There was no significant interaction between ethnicity and treatment at the sixth month follow up (X2=3.0, df=2, p=.22; results not shown). Furthermore, no significant treatment effect was observed at six months for Whites, Blacks, or Hispanics (Table 2b). Combining all three ethnic groups and both treatment conditions, all participants significantly reduced their average volume per week by 6 standard drinks per week (sd =22.7; results not show) at six month follow up (X2=141.6, df=1, p<.001; Table 2c). In addition, those who were employed (B=.36, se=.14, p<.01) or college educated (B=.64, se=.16, p<.0001) consumed more standard drinks per week than the unemployed or those with less than high school education at six month follow up (results not shown). In contrast, patients with more severe injuries consumed fewer standard drinks than those with less severe injuries (Medium vs. Low: B=−1.0, se=.22, p<.0001; High vs Low: B=−1.7, se=.33, p<.0001) at six month follow up (results not shown).

A significant treatment by ethnicity interaction was observed at the 12 month follow up (X2=7.1, df=2, p=.03; results not shown). The treatment effect among Hispanics was significant at 12 month follow up (X2=6.8, df=1, p=.01; Table 2b). Hispanics in the BMI group reduced the average number of standard drinks consumed per week by 8.9 (sd=26.2; Table 2a) at 12 month follow up. However, the effect size was small (d=.14). There was also a significant decrease in volume per week among Hispanics in the TAU+ group at 12 month follow up (X2=42.1, df=1, p<.001; see Table 2c). Hispanics in the TAU+ group reduced their volume per week by an average of 5.7 standard drinks (sd=17.9; Table 2a). No significant treatment effect was observed among Whites and Blacks at twelve months. When combined, Whites and Blacks in the TAU+ and BMI groups significantly reduced their maximum amount at 12 month follow up (X2=26.8, df=1, p<.001; Table 2c) by an average of 3.9 standard drinks per week (sd=22.9; results not shown). In addition, at 12 month follow up patients with an intentional injury (B=.37, se=.17, p<.05) and college education (B=.39, se=.17, p<.01) consumed more standard drinks per week than those with an unintentional injury or those with less than a high school education, respectively (results not shown). In contrast, patients with more severe injuries consumed fewer standard drinks than those with less severe injuries (Medium vs Low: B=−.70, se=.23, p<.01; High vs. Low: B=−1.1, se=.35, p<.01) at 12 month follow up (results not shown).

Maximum Amount

A significant treatment by ethnicity interaction was observed at six month follow up (X2=6.6, df=2, p=.04; results not shown). The treatment effect for Hispanics was significant at 6 month follow up (X2= 8.6, df=1, p=.004; see Table 3b). Hispanics in the BMI group decreased the maximum amount consumed by an average of 9.1 standard drinks (sd=11.9; Table 3) at 6 month follow up. The effect size was small to moderate (d=.29). There was also a significant decrease in maximum amount consumed among Hispanics in the TAU+ group at six month follow up (X2=86.2, df=1, p<.001; see Table 3c). Hispanics in TAU+ group showed an average decrease of 6.2 standard drinks (sd=10; Table 3a) in maximum amount consumed at six month follow up. Whites and Blacks in the TAU+ and BMI groups also significantly reduced maximum amount at 6 month follow up by an average of 4.7 (sd=9.6) standard drinks per week (X2=107.2, df=1, p<.001; see Table 3c). Whites and Blacks in the TAU+ and BMI groups significantly reduced maximum amount at 6 month follow up by an average of 4.7 (sd=9.6) standard drinks per week (results not shown). In addition, at six month follow up, those with college education (B=.42, se=.09, p<.0001) or a high school diploma (B=.25, se=.09, p<.01) drank more standard drinks on the heaviest drinking day than those with less than a high school education (results not shown). In contrast, patients with more severe injuries consumed fewer standard drinks than those with less severe injuries (Medium vs Low: B=−.55, se=.13, p<.0001; High vs Low: B=−1.1, se=.19, p<.0001) at six month follow up (results not shown).

A significant treatment by ethnicity interaction was observed at 12 month follow up (X2=7.9, df=2, p=.02; results not shown). The treatment effect for Hispanics was significant at 12 month follow up (X2= 11.9, df=1, p<.001; Table 3b). The effect size for Hispanics at 12 month follow up was small to moderate (d=.30). Hispanics in the BMI group decreased the maximum amount consumed in one day by 9.1 standard drinks (sd=11.9; Table 3a) at 12 month follow up. There was also a significant decrease in maximum amount consumed among Hispanics in the TAU+ group at 12 month follow up (X2=57.3, df=1, p<.001; Table 3c). Hispanics in TAU+ decreased their maximum amount consumed by 5.9 standard drinks (sd=9.6; Table 3a). Whites and Blacks in both the TAU+ and BMI groups significantly reduced maximum amount at 12 month follow up (X2=53.1, df=1, p<.001; Table 3c). Whites and Blacks in both the TAU+ and BMI groups significantly reduced maximum amount at 12 month follow up by 4.5 standard drinks per week (sd=9.6Table 3b). In addition, at 12 month follow up those with college education (B=.29, se=.10, p<.01) or a high school diploma (B=.39, se=.09, p<.01) drank more standard drinks on the heaviest drinking day than those with less than a high school education (results not shown). In addition, those with an intentional injury (B=.24, se=.10, p<.05) drank more standard drinks on their heaviest drinking day than those with an unintentional injury. In contrast, patients with more severe injuries consumed fewer standard drinks than those with less severe injuries (Medium vs. Low: B=−.35, se=.14, p<.01; High vs. Low: B=−.70, se=.21, p<.01) at 12 month follow up (results not shown).

Percent Days Abstinent

There was no significant interaction between ethnicity and treatment at 6 month (X2=.03, df=2, p>.50) or 12 month follow up (X2=.22, df=2, p>.50; results not shown). No significant treatment effect was observed (Table 4b). For all three ethnic groups in both the TAU+ and BMI, there were significant increases in percent days abstinent at 6 month (X2=44.0, df=1, p<.001; Table 4c) and 12 month follow up (X2=26.2, df=1, p<.001; Table 4c) with a 10% increase (sd=33; results not shown) from baseline to 6 months and an 8% increase (sd=32; results not shown) from baseline to 12 month follow up. In addition, those who were older (B=.002, se=.0009, p<.05), reported prior treatment for substance abuse problems (B=.06, se=.02, p<.01) and those with more severe injuries (Medium vs. Low: B=−.11, se=.03, p<.01; High vs Low: B=−.21, se=.05, p<.0001) had a greater percentage of days abstinent at 6 month follow up (results not shown). Those with a college education (B=−.06, se=.02, p<.05) had a greater percentage of days abstinent than those with less than a high school education at 6 month follow up (results not shown). At 12 month follow up, those who were older (B=.002, se=.001, p<.05), reported prior treatment for substance abuse problems (B=.05, se=.02, p<.05) and those with more severe injuries (Medium vs. Low: B=.09, se=.03, p<.01; High vs. Low: B=.18, se=.05, p<.01) had a greater percentage of days abstinent (results not shown). Males (B=−.05, se=.02, p<.05) had fewer percentage days abstinent than females or those with less than high school education at 12 month follow up (results not shown).

Percent Days Heavy Drinking

The interaction between treatment and ethnicity was marginally significant at 6 month follow up (X2=4.7, df=2, p=.09; results not shown). The treatment effect for Hispanics was significant at 6 month follow up (X2=3.8, df=1, p=.047; Table 5b). The effect size for Hispanics at 6 month follow up was small to moderate (d=.26). Hispanics in the BMI group decreased percent days heavy drinking by 20% (sd=52) at 6 month follow up (Table 5a). For other groups, there were no significant differences in percent days heavy drinking across time (Table 5c). In addition, patients who were married (B=−.13, se=.04, p<.01) had fewer percent days of heavy drinking than those who were single (results not shown).

There was a significant interaction between treatment and ethnicity at 12 month follow up (X2=8.2, df=2, p=.02; results not shown). The treatment effect for Hispanics was significant at 12 month follow up (X2=4.9, df=1, p=.02; Table 5b). The effect size among Hispanics at 12 month follow up was small to moderate (d=.24). Hispanics in the BMI group decreased percent days heavy drinking by 17% (sd=49; see Table 5a) at 12 month follow up. For other groups, there were no significant differences in percent days heavy drinking across time (Table 5c). In addition, patients who were married (B=−.13, se=.04, p<.01) had fewer percent days of heavy drinking than those who were single. Whites and Blacks in both the TAU+ and BMI groups significantly decreased percent days heavy drinking by 7% (sd=4) at 12 month follow up (X2=5.0, df=1, p=.02; see Table 5).

Discussion

Regardless of ethnicity, participants in the TAU+ and BMI groups significantly reduced their drinking at follow up. With the exception of percent days abstinent, there were consistent and significant interactions between treatment assignment and ethnicity with Hispanics receiving BMI demonstrating significant improvements in drinking outcomes. While no significant changes were observed in percent days abstinent, this may be a less relevant outcome in the non-treatment seeking patient population identified in the trauma care setting. In addition, BMI does not emphasize abstinence as an outcome. The findings of a treatment effect among Hispanics are contrary to the a priori hypothesis that brief intervention would be less effective among ethnic minorities. Such expectations stemmed from evidence indicating higher rates of frequent heavy drinking, greater stability of heavy drinking over time and higher rates of alcohol problems among ethnic minorities33–36 As a result of these findings, this discussion addresses factors that may have contributed to the increased effectiveness of BMI among Hispanics and the effectiveness of both BMI and TAU+ in other cases.

The increased effectiveness of BMI among Hispanics may be due to several factors including the fact that a majority of the study clinicians were Hispanic and spoke Spanish fluently. It may be that ethnic concordance between interventionist and participant impacted the effectiveness of the intervention through several mechanisms including cultural scripts or ethnic specific perceptions pertaining to substance abuse. Cultural scripts are patterns of social interaction that are characteristic of a particular cultural group.37 More than being indicative of personal values, cultural scripts are values and beliefs that characterize a particular culture or ethnic group.38 For example, the general tendency to anticipate positive social interactions may have positively influenced Hispanics response to BMI37. In the Hispanic culture family relationships are bound by a strong sense of loyalty and reciprocity.40, 41, 42 This may have contributed to the likelihood that additional support would have been provided to Hispanics. Additional support and advice such as this has been suggested to be an important potential mechanism of change in brief interventions.1 Perhaps most important to the context in which this study was carried out, Hispanics have shown greater willingness to adhere to the advice of medical professionals who are overwhelmingly perceived as the most credible sources of information.45,46. While no concerted effort was made to culturally tailor the training of study clinicians or the intervention itself, an unintended consequence of efforts to recruit and retain Hispanic participants may have increased sensitivity to these and other cultural scripts which may have differentially influence drinking outcomes among Hispanics, particularly when there was an ethnic concordance between the patient and provider. While it could be conceivable that cultural scripts differentially influenced self reported drinking, However, there is currently no research indicating that the validity of self reported drinking varies by ethnicity or level of acculturation. Moreover, there is no compelling reason to believe that this would have differentially influenced self reported drinking by Hispanics in BMI and TAU+.

There are several possible explanations for the observations that TAU+ and BMI groups demonstrated improvements in drinking outcomes. It is possible that regression to the mean led to observed changes in drinking outcomes. However, underreporting of drinking is arguably more likely immediately following an injury when the financial and legal consequences are typically of greatest concern to the patient. In addition, other randomized controlled trials must contend with this possibility as well. In addition to the injury event itself, two limitations of the current study that may have influenced the observed reductions in alcohol intake are the number of patients excluded from participation in the study and follow up rates. However, these are challenges of other studies conducted with injured patients in the trauma care setting. For example, the recruitment and follow up rates in this study are comparable to similar studies and the injury event itself has not been accounted for in these studies. 1,2,5,59 As a result, other factors should be considered as possible explanations for the observed changes in drinking.

The extensive assessment of drinking and other injury related behaviors that were conducted for both treatment groups positively is one possible explanation for changes in drinking following both TAU+ and BMI. A number of researchers have speculated that assessment alone can contribute to positive treatment outcomes.50–53 However, Deappen et al. included a delayed assessment control group and found no evidence for assessment reactivity.54 In the current study, assessment took approximately 30 minutes and was sequenced in a way that may have approximated the intervention condition. The structured assessment may also have precluded judgemental statements or providing unsolicited advice, i.e., interaction styles that are inconsistent with the underlying principles of BMI. Thus, a less sophisticated involving structured assessment and personalized feedback may effectively reduce drinking for many patients. Alternatively, brief intervention conducted as part of this study may not have been sufficiently potent to effect drinking outcomes above and beyond assessment among Whites and Blacks. Longabaugh suggested that brief intervention alone may be less effective in the Emergency Department because urgent medical care necessarily takes precedence5. Finally, while this study represents one of the first studies that evaluated the treatment integrity of BMI, strict adherence to TAU+ was limited in scope in comparison to procedures to maintain adherence to BMI. Thus, it is possible that some bleeding between BMI and TAU+ took place and that this confound varied across patients, the study period and/or therapist. This may be particularly true of patients who reported more severe alcohol problems and were assigned to TAU+. More recent studies and meta-analyses of brief intervention in the Trauma Care and Emergency Department Settings, have also observed similar outcomes across treatment groups.55–61 This study, together with similar studies, suggests that the effectiveness of opportunistic brief alcohol intervention in the trauma care setting and emergency department setting may be more complicated than initial evidence suggested. As trauma centers and emergency departments begin to implement screening and brief intervention, the field will continue to benefit from additional research investigating the factors which potentially impact drinking outcomes. While generally effective, there may be essential elements to the brief intervention, particular contexts in which the brief intervention should be provided or particular patients for whom brief intervention is most effective. A multi-site randomized clinical trial may be the most effective means of identifying potentially factors influencing the effectiveness of brief intervention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant (R01 013824; PI: Caetano) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to the University of Texas School of Public Health

The lead author would like to acknowledge the support of the NIH Health Disparities Loan Repayment Program funded by the National Center of Minority Health and Health Disparities

References

- 1.Gentilello LM, Rivara FP, Donovan DM, Jurkovich GJ, Daranciang E, Dunn CW, et al. Alcohol interventions in a trauma center as a means of reducing the risk of injury recurrence. Ann Surg. 2001;230:473–80. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schermer CR, Moyers TB, Miller WR, Bloomfield LA. Trauma center brief interventions for alcohol disorders decrease subsequent driving under the influence arrests. J Trauma. 2006;60:29–34. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000199420.12322.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gentilello LM, Ebel BE, Wickizer TM, Salkever DS, Rivara FP. Alcohol interventions for trauma patients treated in emergency departments and hospitals: a cost benefit analysis. Ann Surg. 2005;241:541–50. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000157133.80396.1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monti PM, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Spirito A. Brief intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:989–94. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longabaugh R, Woolard RE, Nirenberg TD, Minugh AP, Becker B, Clifford PR, et al. Evaluating the effects of a brief motivational intervention for injured drinkers in the emergency department. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62(6):806–16. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galvin FH, Caetano R. Alcohol Use and Related Problems Among Ethnic Minorities in the United States. Alcohol Res & Health. 2003;27(1):87–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caetano R, Kaskutas LA. Changes in drinking patterns among whites, blacks and Hispanics: 1984–1992. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:558–65. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd MR, Phillips K, Dorsey CJ. Alcohol and other drug disorders, comorbidity, and violence: Comparison of rural African American and Caucasian women. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2003;17:249–258. doi: 10.1053/j.apnu.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caetano R, Kaskutas LA. Changes in drinking problems among Whites, Blacks and Hispanics: 1984–1992. Substance Use & Misuse. 1996;31:1547–1571. doi: 10.3109/10826089609063991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt LA, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Bond J. Ethnic Disparities in Clinical Severity and Services for Alcohol Problems: Results from the National Alcohol Survey. Alcohol: Clin and Exp Res. 2007;31:48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute of Medicine. Broadening the Base of Treatment for Alcohol Problems: Report of a Study by a Committee of the Institute of Medicine, Division of Mental Health and Behavioral Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenbaum S, Hirsh H, Hirsh J. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care: issues in the design, structure and administration of federal healthcare financing programs supported through direct public funding. In: Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. pp. 415–443. [Google Scholar]

- 13.LeFauve CE, Lowman C, Litten RZ, III, Mattson ME. Introduction: National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Workshop on Treatment Research Priorities and Health Disparities. Alcohol: Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1318–20. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080383.74960.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowman C, Lefauve CE. Health disparities and the relationship between race, ethnicity, and substance abuse treatment outcomes. Alcohol: Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1324–26. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080346.62012.DC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Field CA, Claassen CA, O’Keefe G. Association of alcohol use and other high-risk behaviors among trauma patients. The Journal of Trauma. 2001;50(1):13–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200101000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Field CA, O’Keefe G. Behavioral and psychological risk factors for traumatic injury. The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2004;26(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2003.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) guidelines. Suggest: Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/guide.pdf.

- 18.Ewing JA. Detecting Alcoholism: The CAGE Questionaire. JAMA. 1984;252:1905–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitchens JM. Does this patient have an alcohol problem? . JAMA. 1994;272(22):1782–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Field CA, Caetano R, Pezzia C. Process Evaluation of Serial Screening Criteria to Identify Injured Patients That Benefit From Brief Intervention: Practical Implications. J Trauma. 2008 doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181808101. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rehm J, Room R, Graham K, Monteiro M, Gmel G, Sempos CT. The relationship of average volume of alcohol consumption and patterns of drinking to burden of disease: An overview. Addiction. 2003;98(9):1209–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenfield TK. Ways of measuring drinking patterns and the difference they make: Experience with graduated frequencies. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;12:33–49. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Midanik LT. Comparing usual quantity/frequency and graduated frequency scales to assess yearly alcohol consumption: Results from the 1990 U.S. national alcohol survey. Addiction. 1994;89:407–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dawson DA. Methodological issues in measuring alcohol use. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27(1):18–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunn C, Hungerford DW, Field C, McCann B. The stages of change: when are trauma patients truly ready to change? . J trauma. 2005;59:S27–32. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000185298.24593.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Field C, Hungerford DW, Dunn C. Brief motivational interventions: an introduction. J trauma. 2005;59:S21–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000179899.37332.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, Congdon R. HLM 6: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. 2. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gentilello LM, Rivara FP, Donovan DM, Jurkovich GJ, Daranciang E, Dunn CW, et al. Alcohol interventions in a trauma center as a means of reducing the risk of injury recurrence. Ann Surg. 1999;230:1–11. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soderstrom CA, DiClemente CC, Dischinger PC, Hebel JR, McDuff DR, Auman KM, et al. A controlled trial of brief intervention versus brief advice for at-risk drinking trauma center patients. J Trauma. 2007;62(5):1102–11. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31804bdb26. discussion 1111–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosnow RL, Rosenthal R. Computing contrasts, effect sizes, and counternulls on other people’s published data: General procedures for research consumers. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:331–40. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sutocky JW, Schultz JM, Kizer KW. Alcohol-related mortality in California, 1980 to 1989. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83:817–23. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.6.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caetano R, Clark C. Trends in alcohol-related problems among whites, blacks, and Hispanics: 1984–1995. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:534–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caetano R. Prevalence, incidence and stability of drinking problems among whites, blacks and Hispanics: 1984–1992. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:565–72. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caetano R, Kaskutas LA. Changes in drinking patterns among whites, blacks and Hispanics: 1984–1992. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:558–65. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trandis H, Marin G, Lasinsky J, Betancourt H. Simpatia as a cultural script of Hispanics. J Personality and Social Psych. 1984;47:1363–1375. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marin G, Gamba RJ. Acculturation and changes in cultural values. In: Chun KM, Balls-Organista P, Marin G, editors. Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change. NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sabogal F, Marin G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marin BV, Perez-Stable EJ. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? . Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaines SO, Rios DI, Buriel R. Familism and personal relationship process among Latina/Latino couples. In: Gaines SO, Liu JH, Buriel R, Rios DI, editors. Culture, Ethnicity, and Personal Relationship Processes. New York: Routledge; 1997. pp. 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawrence RH, Bennett JM, Markides KS. Perceived intergenerational solidarity and psychological distress among older Mexican Americans. Journal of Gerontology. 1992;47:S55–S65. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.2.s55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marin BV, Marin G, Perez-Stable EJ, Otero-Sabogal R, Sabogal F. Cultural differences in attitudes toward smoking: Developing messages using the theory of reasoned action. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1990;20:478–93. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marin BV, Marin G, Juarez R. Differences between Hispanics and non-Hispanics in willingness to provide AIDS prevention advice. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1990;12:153–64. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marin G, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Sabogal F, Perez-Stable EJ. The role of acculturation in the attitudes, norms, and expectancies of Hispanic smokers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1989;20:399–415. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marin G, Marin BV. Perceived credibility of channels and sources of AIDS information among Hispanics. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1990;2(2):154–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peterson J, Marin G. Issues in the prevention of AIDS among Black and Hispanic men. Amer Psych. 1988;43(11):871–77. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.43.11.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marin G. AIDS prevention among Hispanics: Needs, risk behaviors, and cultural values. Public Health Reports. 1989;104:411–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marin G, Burhansstipanov L, Connell C, Gielen AC, Helitzer-Allen D, Lorig K, et al. A research agenda for health education among underserved populations. Health Education Quarterly. 1995;22(3):346–63. doi: 10.1177/109019819402200307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bien TH, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a review. Addiction. 1993;88:315–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clifford P, Maisto S. Subject reactivity effects and alcohol treatment outcome research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:787–93. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Project MATCH Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH three-year drinking outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;21:1300–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sobell MB, Brochu S, Sobell LC, Roy J, Stephens JA. Alcohol treatment outcome evaluation methodology: State of the art 1980–1984. Addictive Behaviors. 1987;12:113–128. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Daeppen JB, Gaume J, Bady P, Yersin B, Calmes JM, Givel JC, et al. Brief alcohol intervention and alcohol assessment do not influence alcohol use in injured patients treated in the emergency department: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Addiction. 2007;102(8):1224–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saitz R, Palfai TP, Cheng DM, Horton NJ, Freedner N, Dukes K, et al. Brief intervention for medical inpatients with unhealthy alcohol use. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:167–76. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soderstrom CA, DiClemente CC, Dischinger PC, Hebel JR, McDuff DR, Auman KM, et al. A controlled trial of brief intervention versus brief advice for at-risk drinking trauma center patients. J Trauma. 2007;62(5):1102–11. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31804bdb26. discussion 1111–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Havard A, Shakeshaft A, Sanson-Fisher R. Systematic review and meta-analyses of strategies targeting alcohol problems in emergency departments: interventions reduce alcohol-related injuries. Addiction. 2008;103(3):368–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daeppen JB. A meta-analysis of brief alcohol interventions in emergency departments: few answers, many questions. Addiction. 2008;103(3):377–78. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sommers MS, Dyehouse JM, Howe SR, Fleming M, Fargo J, Schafer JC. Effectiveness of brief interventions after alcohol-related vehicular injury: a randomized controlled trial. J Trauma. 2006;61:523–33. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000221756.67126.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.D’Onofrio G, Pantalon MV, Degutis LC, Fiellin DA, Busch SH, Chawarski MC, et al. Brief intervention for hazardous and harmful drinkers in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:742–50. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaboration. The impact of screening, brief intervention, and referral for treatment on emergency department patients’ alcohol use. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.06.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Dunn CW. The efficacy of motivational interviewing and its adaptations: What we know so far. In: Miller WR, Rollnick S, editors. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y, Bond J, Borges G. Causal attribution of alcohol and injury: a cross-national meta-analysis from ERCAAP. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2003;27:1805–12. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000095863.78842.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dunn CW, DeRoo L, Rivara FP. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: A systematic review. Addiction. 2001;96:1725–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961217253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]