Summary

Regulatory T (Treg) cells play essential roles in maintaining immune homeostasis. While Foxp3 expression marks the commitment of progenitors to Treg lineage, how Treg cells are generated during lymphocyte development remains enigmatic. Both NFAT and Smad have been implicated in Foxp3 gene activation, but mice deficient in them are reported to have normal Treg cell numbers. We report here that c-Rel controls the development of Treg cells by promoting the formation of a Foxp3-specific enhanceosome that contains c-Rel, p65, NFAT, Smad, and CREB. Although Smad and CREB first bind to Foxp3 enhancers, they later move to the promoter to form the c-Rel enhanceosome. Consequently, c-Rel-deficient mice have up to ten-fold reductions in Treg cells, and c-Rel-deficient T cells are significantly compromised in Treg differentiation. Thus, Treg development is controlled by a c-Rel enhanceosome, and strategies targeting Rel/NF-κB can be effective for manipulating Treg function.

Keywords: Regulatory T cell, Foxp3, transcription factor, Rel/NF-κB, immune regulation

Introduction

Regulatory T (Treg) cells are a heterogeneous population of T lymphocytes that play crucial roles in maintaining immune homeostasis and preventing autoimmune diseases (Bommireddy and Doetschman, 2007; Lohr et al., 2006; Sakaguchi et al., 2006; Shevach et al., 2006). The CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ (forkhead box P3+) ‘naturally occurring’ Treg (nTreg) cells are generated in the thymus and are among the best-studied Treg cells (Sakaguchi et al., 2006). In mice, nTreg cells appear to migrate to the periphery by day 3 after birth, as thymectomy at day 3, but not after, leads to autoimmunity. Thymic development of Treg cells requires T cell receptor (TCR) and costimulatory signaling as mice deficient in these molecules have reduced nTreg cell numbers (Sakaguchi et al., 2006). Thymic stromal cells not only provide the peptide-MHC complexes to engage immature TCRs, but they are also the source of secondary signals involved in dictating lineage commitment. Reports indicate that the development of Foxp3+ thymocytes is linked to that of the medullary thymic epithelium. The majority of Foxp3-expressing thymocytes are localized to the medullary region of the thymus (Fontenot et al., 2005a).

Unlike nTreg cells, the CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ ‘induced’ Treg (iTreg) cells can be generated in peripheral lymphoid organs, or in cultures, following stimulation with antigens and Treg-inducing cytokines such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (Bommireddy and Doetschman, 2007; Liang et al., 2005; Lohr et al., 2006). In addition to nTreg and iTreg cells, other types of Treg cells have also been described. These include CD8+ Treg cells, Tr1 cells, and Th3 cells (Chen et al., 1994; O’Garra and Vieira, 2004; Shevach, 2006).

The Foxp3 protein is the most distinct marker of nTreg cells and is crucial for their function. Scurfy mice that carry a Foxp3 gene mutation present lymphoproliferation, lymphocytic infiltration and multi-organ autoimmune diseases (Godfrey et al., 1991). Similarly, Foxp3 gene mutation in humans causes a fatal autoimmune disorder called IPEX (immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked) (Bennett et al., 2001). Foxp3 protein, named for its winged helix-forkhead DNA binding domain, functions as a transcription factor. Full-length Foxp3 holds high sequence homology across mammalian species (Fontenot et al., 2005b). Scurfy affects males, but not heterozygous females because Foxp3 gene is located on X-chromosome. Random X-inactivation in heterozygous females results in a combination of cells with normal and defective Foxp3 expression (Tommasini et al., 2002). Scurfy mice are deficient in CD4+CD25+ T cells, and autoimmune diseases in these mice can be prevented by adoptive transfer of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells (Bennett et al., 2001; Khattri et al., 2003).

While Foxp3 gene expression marks the commitment of progenitor cells to Treg lineage, transcription factors that switch on Foxp3 gene during T cell development are not well defined. The Foxp3 gene is controlled by a core promoter and at least three distal enhancers (Lal et al., 2009; Mantel et al., 2006; Tone et al., 2008). Whether a single enhanceosome (i.e., enhancer complex) that bridges all these regulatory elements, or multiple modular enhancer complexes are formed in Treg cells is not known. Recent studies indicate that NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T-cells) and Smad may play crucial roles in activating the Foxp3 gene (Tone et al., 2008). However, mice deficient in one or two of these factors have no significant reductions in Treg cell numbers (Bommireddy and Doetschman, 2007; Bopp et al., 2005), indicating that other factors are required for Treg differentiation.

The mammalian Rel/nuclear factor (NF)- κB family consists of five members: c-Rel, RelA/p65, RelB, NF-κB1 (p50/p105), and NF-κB2 (p52/p100) (Barnes and Karin, 1997; Beg and Baltimore, 1996). Unlike other members that are constitutively expressed in multiple cell types, c-Rel is expressed primarily in lymphoid tissues by lymphoid and myeloid cells (Brownell et al., 1987; Gerondakis et al., 1998; Huguet et al., 1998; Simek and Rice, 1988; Wang et al., 1997). c-Rel-deficient mice do not suffer from developmental problems or infectious diseases, and c-Rel-deficient T cells are competent in survival and Th2 type responses, but are significantly compromised in their Th1 type responses (Hilliard et al., 2002; Tumang et al., 1998). We report here that c-Rel plays a crucial role in assembling a Foxp3-specific enhancer complex that is required for initiating Treg differentiation.

Results

Treg development is markedly diminished in c-Rel-deficient mice

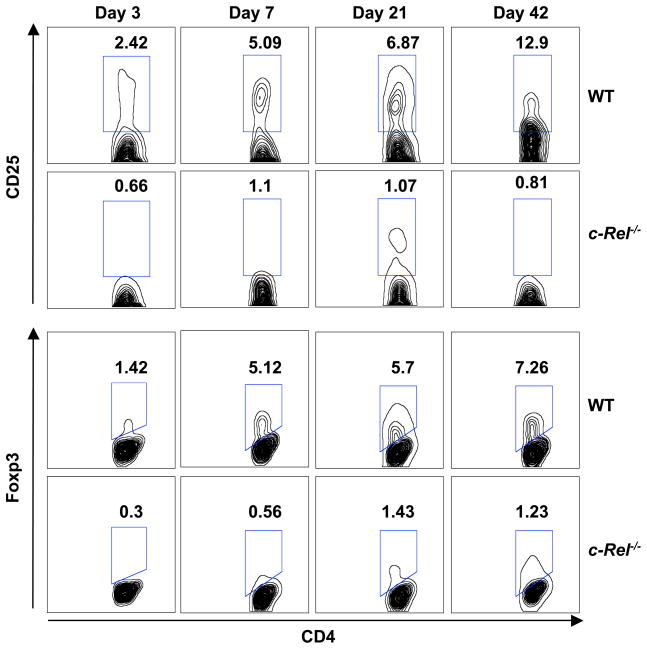

The thymus is the central lymphoid organ that gives rise to both Foxp3+ regulatory T cells and Foxp3− naïve T cells (Fontenot and Rudensky, 2005; Kim, 2006; Kim and Rudensky, 2006; Sakaguchi, 2005; Ziegler, 2006). c-Rel is a member of the Rel/NF-κB family that is preferentially expressed in lymphoid organs (Simek and Rice, 1988). To determine the roles of c-Rel in the development of Treg and naïve T cells, we examined their frequencies in the thymus of 3-, 7-, 21-, and 42-day-old C57BL/6 mice that do or do not express c-Rel (Figure 1 and Table 1). Although the total number of thymocytes was reduced by ~20% in c-Rel-deficient mice, the frequencies of CD4+CD25−Foxp3− naïve T cells were comparable in the two groups. By contrast, up to 10-fold reductions of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ nTreg cells were observed in c-Rel-deficient thymus of both neonatal and adult mice (Table 1). For 6-week-old mice, the frequency of CD4+CD8−CD25+Foxp3+ nTreg cells was reduced from 2.7%±0.9 in the WT group to 0.2%±0.1 in the c-Rel-deficient group (p<0.0001) (Table 1). Consistent with this finding, the frequencies of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells were also markedly reduced in the spleens of c-Rel-deficient mice, regardless of ages (Figure S1 and Table S1). Up to 4-fold reductions were observed on day 3 and ~5-fold reductions were observed on day 42 in the c-Rel-deficient group (Table S1). These results indicate that c-Rel is required for the thymic development of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ nTreg cells, but dispensable for that of Foxp3− naïve T cells.

Figure 1. Intra-thymic development of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells is markedly abated in c-Rel−/− mice.

Thymocytes from wild type (WT) and c-Rel−/− C57BL/6 mice (n=6) were collected 3, 7, 21, and 42 days after birth, stained with antibodies to CD4, CD8, CD25, and Foxp3, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Results shown are contour plots of CD4+ T cells, and are representative of three independent experiments. Numerical figures in each panel represent the percentages of CD4+ T cells in the gate.

Table 1.

c-Rel deficiency selectively blocks intra-thymic development of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells, but not that of Foxp3− T cells.

| Day | Mice (n=6) | Thymocytes per mouse (× 10−5) | CD4+CD8− (% of thymocytes) | CD4+CD8− CD25+ (%)a, b | CD4+CD8− Foxp3+ (%)a, b | CD4+CD8− CD25+Foxp3+ (%)a, b | CD4+CD8− CD25− Foxp3− (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | WT | 100±15 | 17±2.3 | 2.0±0.4 | 1.2±0.2 | 0.8±0.2 | 97.8±1.7 |

| c-Rel−/− | 80±8 | 17±1.8 | 0.4±0.2 | 0.2±0.1 | 0.1±0.1 | 99.5±1.5 | |

| 7 | WT | 600±80 | 16±2.2 | 4.8±1.2 | 4.7±0.5 | 2.6±0.9 | 93.7±1.5 |

| c-Rel−/− | 500±75 | 10±2 | 0.9±0.3 | 0.5±0.2 | 0.3±0.1 | 97.2±0.9 | |

| 21 | WT | 1,100±120 | 14±1.5 | 6.2±0.8 | 5.2±0.9 | 4.1±0.8 | 91.5±1.4 |

| c-Rel−/− | 1,000±110 | 13±1.2 | 0.8±0.3 | 1.2±0.3 | 0.5±0.2 | 97.8±0.8 | |

| 42 | WT | 1,900±250 | 6.5±0.9 | 11.9±1.5 | 6.2±1.2 | 2.7±0.9 | 86.6±2.9 |

| c-Rel−/− | 1,700±220 | 6±1.3 | 0.7±0.2 | 0.7±0.7 | 0.2±0.1 | 99.5±1.6 |

% of CD4+ T cells.

The differences between WT and c-Rel−/− groups are statistically significant (p<0.001) for all days.

c-Rel-deficient T cells are defective in Foxp3 gene expression and iTreg differentiation

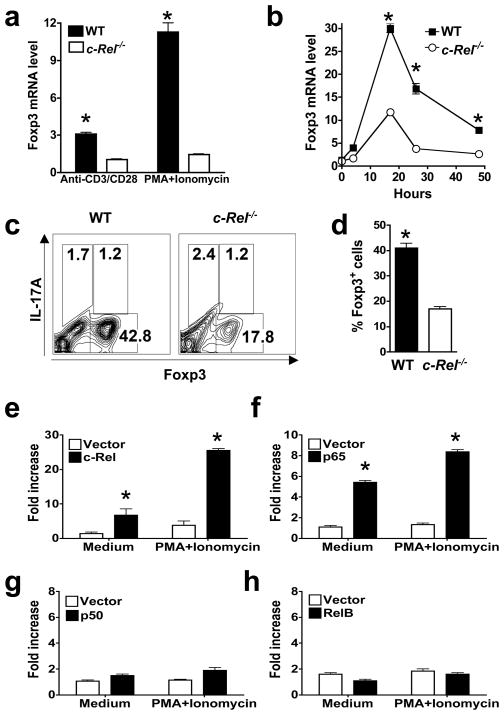

To determine the effect of c-Rel deficiency on Foxp3 gene expression and Treg differentiation, we measured Foxp3 mRNA levels in T cells by quantitative PCR. We found that Foxp3 mRNA was markedly reduced in splenic CD4+ T cells isolated from c-Rel-deficient mice following stimulation with either anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28, or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) plus ionomycin (Figure 2a). Similarly, when purified naive T cells were cultured under Treg-inducing conditions in vitro, Foxp3 mRNA expression was significantly reduced in the c-Rel-deficient group (Figure 2b). Consistent with these findings, the frequency of iTreg cells generated in the culture was also significantly reduced in the c-Rel-deficient group (Figure 2, c and d). On the other hand, over-expression of c-Rel increased Foxp3 expression in both primary T cells and the EL-4 T cell line (Figure S2). These results indicate that c-Rel may directly control iTreg differentiation through Foxp3 gene.

Figure 2. c-Rel deficiency blocks Foxp3 gene expression and Treg differentiation, whereas c-Rel co-expression increases Foxp3 promoter activity.

(a) Reduced Foxp3 mRNA expression in c-Rel−/− splenic T cells. Splenic CD4+ T cells were purified from 6-week-old WT and c-Rel−/− mice (n=5) and stimulated with anti-CD3 (2 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml) for 6 hrs, or PMA (50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (1 μM) for 2 hrs. Total RNA was extracted and Foxp3 mRNA levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR. (b) Reduced Foxp3 mRNA expression in c-Rel−/− T cells during Treg differentiation. Purified CD4+CD25− splenic T cells were cultured in the presence of plate-bound anti-CD3 (5 μg/ml), soluble anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml), IL-2 (50 U/ml), anti-IL-4 (1 μg/ml), anti-IFN-γ (1 μg/ml), and TGF-β (5 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Total RNA was extracted and Foxp3 mRNA levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR. (c–d) Reduced Treg differentiation of c-Rel−/− T cells. CD4+CD25− T cells were cultured as in panel b for three days, re-stimulated with PMA (50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (1 μM) for 4 hrs, stained with antibodies to IL-17A and Foxp3, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (e–h) Activation of the Foxp3 promoter by c-Rel and p65, but not p50 or RelB. EL4/LAF cells were transiently transfected with murine Foxp3 promoter luciferase constructs together with an expression vector for full-length c-Rel (e), p65 (f), p50 (g), or RelB (h), or the empty vector as indicated. After 24 hrs, cells were treated with or without PMA (50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (1 μM) for 5 hrs, and the luciferase activities measured. The promoter activity is presented as fold increase over cells transfected with empty vector but not treated with PMA and ionomycin. To normalize the transfection efficiency across samples, the Renilla luciferase expression vector pRLTK was used as an internal control. *, The differences between the two groups are statistically significant (p<0.001 for all marked data points in this figure). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

c-Rel and p65 activate the Foxp3 promoter

To test the theory that Rel/NF-κB proteins control Foxp3 gene expression, we first determined whether they activate the Foxp3 promoter in a luciferase-based promoter reporter assay. We found that c-Rel and p65, but not p50 or RelB, activated significantly the Foxp3 promoter upon co-expression (Figure 2, e–h). Of note is that the Foxp3 promoter is extremely weak in the absence of co-expressed c-Rel or p65, a finding consistent with previous reports about this promoter (Mantel et al., 2006; Tone et al., 2008). These results indicate that p50 and RelB may not be as crucial as c-Rel for Treg differentiation. Consistent with this view, p50-deficient mice only have slightly reduced numbers of Treg cells in the spleen, but not in the thymus when compared to WT mice (Figures S3), and RelB-deficient mice have relatively normal numbers of Treg cells (Figure S4). Interestingly, recent reports indicate that mice carrying a mutated p105 (the precursor form of p50) have reduced Treg numbers (Sriskantharajah et al., 2008), and mice deficient in IKKβ (inhibitor of κB kinase β) or doubly deficient in two Rel/NF-κB members have reduced CD4+CD25+ T cells, although Foxp3+ Treg cells in these mice were not determined (Schmidt-Supprian et al., 2003; Zheng et al., 2003). Taken together, these findings indicate that members of the Rel/NF-κB family may regulate Foxp3 gene expression during Treg development in a member-specific manner.

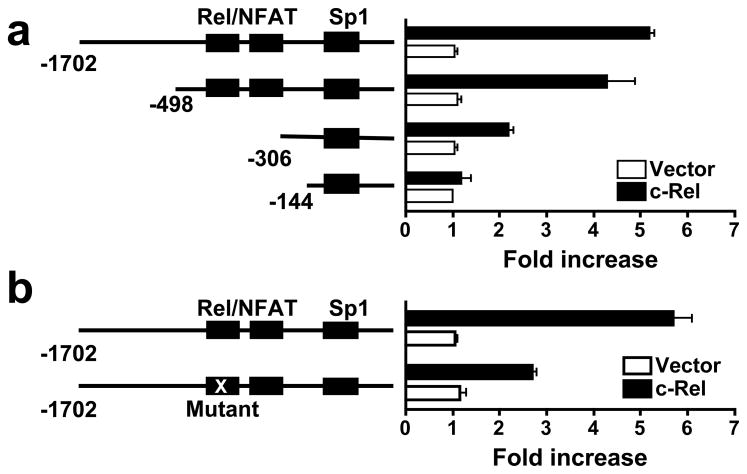

c-Rel binds to the Foxp3 promoter through two unique Rel/NFAT sites

To identify the c-Rel-responsive region in the murine Foxp3 promoter, we performed deletional analysis of the promoter. We found that nucleotides −498 to −144 were required for the c-Rel activity (Figure 3a). A close examination of the murine nucleotide sequence in this region revealed two putative Rel/NF-κB binding sites (−382 to −376, and −327 to −321) that are identical in sequence to previously designated NFAT sites in the human FOXP3 promoter (Mantel et al., 2006). NFAT and c-Rel can bind to same nucleotides (containing TTCC) on many gene promoters because they both use the N-terminal Rel homology domain (conserved between them) to bind DNA (Rao et al., 1997). To determine whether these sites are required for c-Rel action, we mutated nucleotides TTCC (position −379 to −376) to TGGA. This significantly reduced the effect of c-Rel on the promoter (Figure 3b), indicating that c-Rel regulates Foxp3 promoter through this site.

Figure 3. c-Rel activates the Foxp3 promoter through unique Rel/NFAT sites.

(a) The Foxp3 promoter region required for c-Rel activity. Deletion mutants of the Foxp3 promoter were analyzed in a luciferase reporter assay as in Figure 2 with or without c-Rel co-transfection. Binding sites for Rel/NFATc2 and Sp1 are indicated. (b) The Rel/NFAT site of the Foxp3 promoter required for c-Rel activity. Wild type and Rel/NFAT site-mutated Foxp3 promoters were analyzed in a luciferase reporter assay as in Figure 2 with or without c-Rel co-transfection. Data are representative of three independent experiments. *, p<0.01.

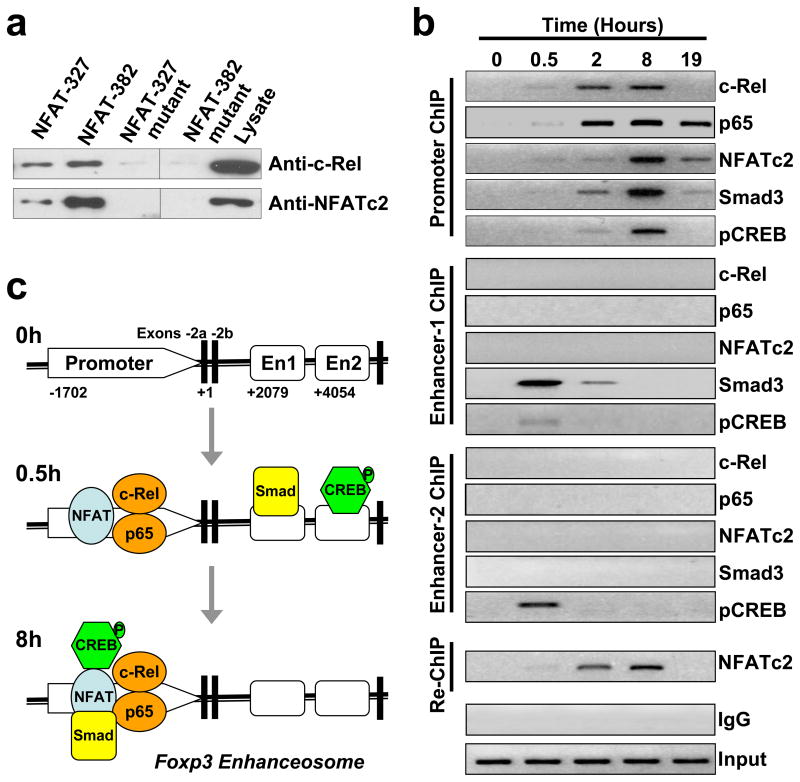

To establish whether c-Rel is indeed able to bind to the NFAT nucleotides, we performed nucleotide pull-down analyses using both wild type and mutant NFAT nucleotides. We found that similar to NFATc2, c-Rel readily bound to the 33-mer nucleotides of both NFAT sites, but not their mutants (Figure 4a). For these reasons, we named these sites the “Rel/NFAT” sites.

Figure 4. Visualizing the formation of a unique c-Rel enhanceosome at the Foxp3 promoter.

(a) Binding of c-Rel to Rel/NFAT oligonucleotides as determined by nucleotide pull-down. Nuclear extracts were prepared from EL4/LAF cells after stimulation for 6 hours with PMA and ionomycin. Biotinylated Rel/NFAT oligonucleotides or their mutants were absorbed by streptavidin-agarose beads, and then added to the nuclear extracts. The amount of c-Rel and NFATc2 proteins in the precipitates were assessed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Rel and anti-NFATc2, respectively. Total nuclear extract were also tested as controls. (b) Binding of c-Rel, p65, NFATc2, Smad3, and pCREB (phospho-CREB) to the Foxp3 locus as determined by ChIP and Re-ChIP. Purified CD4+CD25− T cells from C57BL/6 mice were cultured under Treg-inducing conditions as in Figure 2b, and harvested at the indicated times. Cells were then analyzed by ChIP for c-Rel, p65, NFATc2, Smad3, and pCREB bindings to the promoter, enhancer-1, and enhancer-2 of the Foxp3 gene as described in Experimental Procedures. Re-ChIP was performed for NFATc2 binding to the promoter using DNA precipitated by anti-c-Rel. Control IgG and input DNA shown are for promoter ChIP. (c) Schematic view of the 5′ end of the Foxp3 locus. The kinetics of the enhanceosome formation from 0 to 8 hours (h) is constructed based on data shown in panel (b). En, enhancer. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

c-Rel orchestrates the formation of a Foxp3-specific enhanceosome that contains c-Rel, p65, NFAT, Smad, and CREB

To determine the nature of the transcriptional complexes formed at the Foxp3 locus during Treg differentiation, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and sequential ChIP (SeqChIP or Re-ChIP). The Foxp3 DNA:transcription factor complexes were precipitated using specific antibodies to c-Rel, p65, NFATc2, Smad3, and pCREB (phospho-cAMP response element binding protein) at different time points of Treg differentiation. The nature of the precipitated DNA was then defined by PCR using primers specific for the core promoter or each of the two enhancers of the Foxp3 gene as detailed in Experimental Procedures. Re-ChIP was used to ascertain whether c-Rel and NFAT simultaneously associated with the same DNA sequence. In the Re-ChIP, c-Rel:DNA complexes from the first immunoprecipitation (with anti-c-Rel) were subjected to an additional round of immunoprecipitation with anti-NFATc2 (Figure 4b).

We found that in resting CD4+CD25− T cells, the Foxp3 promoter and enhancers were completely devoid of any transcription factors tested (time 0, Figure 4b). By 0.5 hour after stimulation with Treg-inducing factors, c-Rel, p65, and NFATc2 started to appear at the promoter site while Smad bound to enhancer-1, and pCREB occupied both enhancers 1 and 2. Remarkably, 8 hours after stimulation, both Smad and pCREB completely dissociated from the enhancers, but emerged at the promoter site, coinciding with a strong occupation of the promoter by c-Rel, p65, and NFATc2 (Figure 4, b and c). By the 19th hour, c-Rel and pCREB disappeared from the promoter with NFATc2, Smad, and p65 remaining. Of the five transcription factors tested, c-Rel and p65 appeared to be the first to occupy the promoter; their binding peaked at the 2nd hour as opposed to 8th hour for other factors. Re-ChIP assay confirmed that c-Rel and NFATc2 were indeed in the same complex (Figure 4b).

Because we did not detect an association between the enhancers and c-Rel, p65, or NFATc2, we propose that the enhancers may not ‘loop’ back to the promoter to form the enhanceosome. Instead, after engaging their specific enhancers, Smad and CREB may simply ‘scan’ the Foxp3 locus until they reach the promoter complex formed by c-Rel, p65, and NFAT, leading to the maturation of the enhanceosome (Figure 4c). Similar scanning mechanism has been previously proposed for other genes (Bondarenko et al., 2003). Of note is that NFATc1 may also bind to enhancer-1 at a later time point (24 hours after stimulation) (Tone et al., 2008).

TGF-β plays an important role in iTreg generation. To determine its effect on the assembly of the c-Rel enhanceosome, we repeated the ChIP and re-ChIP assays using cells that were not treated with exogenous TGF-β (Figure S5). We found that TGF-β affected primarily the recruitment of Smad to the Foxp3 promoter while having little effect on that of other transcription factors tested. The level of Foxp3 mRNA was extremely low in cultures without exogenous TGF-β, and did not increase during Treg differentiation as measured by real-time PCR (Figure S6). However, a small, but detectable number of Treg cells were generated in the absence of exogenous TGF-β, as determined by flow cytometry (Figure S6a). In the presence of TGF-β, Foxp3+ T cells increased from 0.82% to ~17% during the first 18 hours of Treg differentiation, and reached ~40% at the end of the culture.

c-Rel regulates Treg differentiation in a cell-autonomous manner

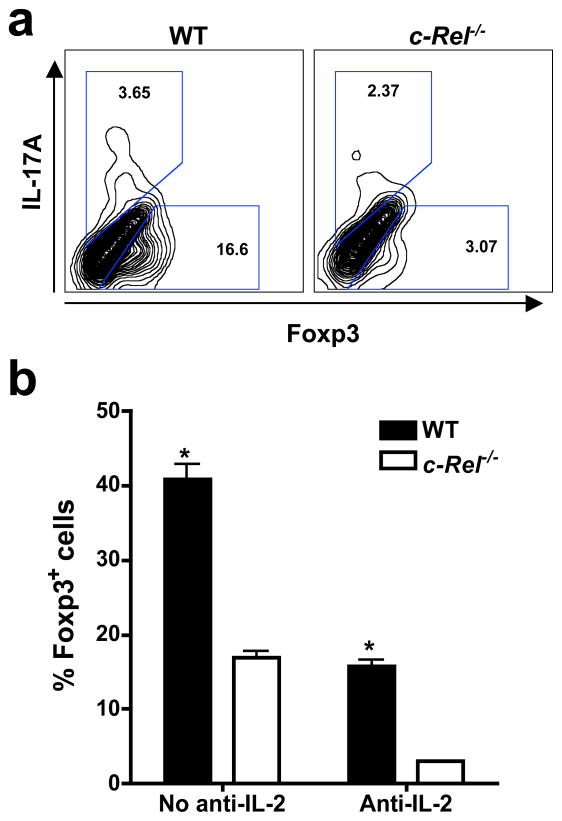

IL-2 plays an important role in Treg development (Lohr et al., 2006). c-Rel-deficient T cells have a partial defect in IL-2 production when cultured in vitro (Liou et al., 1999). To determine the degree to which c-Rel regulates iTreg differentiation independent of IL-2, we studied iTreg differentiation in the presence of a neutralizing IL-2 antibody. While anti-IL-2 significantly reduced the number of iTreg cells generated, c-Rel-deficient T cells were equally defective in iTreg differentiation, indicating that they have an intrinsic defect in the Treg differentiation program (Figure 5). Combined with the finding that c-Rel-deficient T cells were defective in iTreg differentiation even when treated with excess amounts of IL-2 (Figure 2, b–d), these results indicate that IL-2 may not be responsible for the defective Treg differentiation of c-Rel-deficient T cells in the culture. Therefore, c-Rel may directly control Treg differentiation in a cell-autonomous manner.

Figure 5. c-Rel mediates Treg differentiation independent of IL-2.

(a) Purified CD4+CD25− T cells from 6-week-old WT and c-Rel−/− mice (n=5) were cultured in the presence of plate-bound anti-CD3, soluble anti-CD28, anti-IL-2 (1 μg/ml), anti-IL-4, anti-IFN-γ, and TGF-β for three days, re-stimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 4 hours, stained with antibodies to IL-17A and Foxp3, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (b) Percentages of CD4+Foxp3+ cells after in vitro Treg differentiation as shown in panel a, in the presence or absence of anti-IL-2. Results are representative of three independent experiments. *, p<0.001.

To test this theory, we generated two types of mixed bone marrow chimeric mice in whom the WT and c-Rel−/− bone marrow cells were present at different ratios. We found that c-Rel−/− bone marrow cells gave rise to significantly less Foxp3+CD4+ nTreg cells than WT bone marrow cells regardless of the bone marrow cell ratios used (Figure S7).

Discussion

How Treg cells are generated remains enigmatic. Results reported here enable us to propose the following model, which may apply at least to iTreg cells (Figure S8). Antigen-presenting cells (APC) carrying specific peptides engage precursor T cells by TCR and CD28, in the presence of TGF-β (Chen et al., 2003; Kretschmer et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2003); ligation of TCR, CD28, and TGF-β receptors leads to the activation of IKKβ, which phosphorylates IκBα (inhibitor of κBα), releasing c-Rel and p65; the freed c-Rel-p65 dimer migrates into the nucleus, binds to the Foxp3 promoter, and initiates Treg differentiation, with the help of NFATc2, CREB, and Smad (Bommireddy and Doetschman, 2007; Oh-Hora et al., 2008). While TGF-β may regulate Treg differentiation through Smad (Bommireddy and Doetschman, 2007; Liu et al., 2008; Tone et al., 2008), it can also activate the Rel/NF-κB pathway through the TGF-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK-1) (Lu et al., 2007). For clarity, other regulatory factors and epigenetic changes of the Foxp3 gene are not depicted in Figure S8.

If the Foxp3 promoter is regulated by several transcription factors, how is c-Rel deficiency alone able to markedly abate Treg differentiation? We propose that the Foxp3 promoter is regulated by a Treg-specific enhanceosome comprising essential transcription factors such as c-Rel, p65, Smad, and NFAT (Figure S8); the enhanceosome operates as a ‘coincidence detector’, turning on Foxp3 promoter only when all the essential transcription factors are present (either sequentially or concurrently), and lacking any one of them leaves the promoter dormant (Merika and Thanos, 2001). This model also explains how Treg-specific Foxp3 gene expression can be specified by factors such as c-Rel, p65, Smad, and NFAT that are not strictly Treg-specific. The presence of any of these factors alone is insufficient to drive Foxp3 gene expression, and the presence of all these factors, which may occur only under Treg-inducing condition, is required for Treg differentiation. Many gene promoters follow the principle of the enhancesome model (Merika and Thanos, 2001). Thus, in order to initiate the Treg differentiation program, at least four classes of transcription factors, i.e., NFAT, Smad, CREB, and c-Rel, must be transported to the Foxp3 promoter. Manipulating the function of any of these factors is sufficient to alter the Treg differentiation program. It is to be noted that, unlike c-Rel-deficient mice that have a severe defect in Treg differentiation, mice deficient in one or two of the Smad or NFAT family members have no significant reductions in Treg cell numbers (Bommireddy and Doetschman, 2007; Bopp et al., 2005). This may be due to compensation by other members of the Smad or NFAT family, which may form the enhanceosome together with c-Rel. This notion is supported by the report that Stim1 and Stim2 knockout mice, which have defects in the activation of all NFAT proteins, have reduced Treg cells (Oh-Hora et al., 2008).

How enhancers enhance the activities of promoters that are kilobases away has puzzled biologists for decades. It is generally accepted that enhancer-binding factors can form large transcriptional complexes with promoter-binding factors to enhance the promoter activity. This may be achieved by three distinct, but not mutually exclusive, processes, which are known as ‘looping’, ‘scanning’, and ‘linking’ mechanisms (Bondarenko et al., 2003). Although the scanning mechanism explains all the ChIP data we report here, we do not know all the components of the c-Rel enhanceosome formed at the Foxp3 promoter. Nor can we rule out the possibility that Smad and NFAT found at the promoter and enhancers are from different pools of factors. Scaffold proteins are crucial for enhanceosome formation (Merika and Thanos, 2001). Their role in the formation of the c-Rel enhanceosome remains to be established.

The Foxp3 gene is ‘turned off’ in most cell types by at least two epigenetic mechanisms: 1) its close association with histones (which prevents its access by activating factors), and 2) its methylation in the regulatory regions (which makes it ‘unreadable’ by activating factors) (Baron et al., 2007; Janson et al., 2008; Kim and Leonard, 2007; Lal et al., 2009; Mantel et al., 2006; Polansky et al., 2008; Tone et al., 2008). In order to ‘switch on’ Foxp3 gene and to maintain stable Foxp3 expression, the histones that cover Foxp3 DNA have to be acetylated and removed, and the methylated DNA regions of the Foxp3 have to be de-methylated. These epigenetic changes at the Foxp3 locus are hallmarks of nTreg cells and are the reason why Foxp3 gene is “On” in Treg but “Off” in non-Treg cells.

The epigenetic changes at the Foxp3 locus are likely initiated by the enhanceosome identified in this study. Both Rel/NF-κB and pCREB can directly recruit histone-modifying enzymes, e.g., histone acetyltransferases p300 and CBP (CREB-binding protein). Additionally, the c-Rel enhanceosome may also control DNA methylation by blocking the access of DNA methyltransferase to cytosine residues. Further studies are needed to test these possibilities.

In addition to reducing Foxp3 expression, c-Rel deficiency also affected CD25 expression (Figures 1 and S1). This may be a result of reduced generation of Treg cells. Alternatively, it may be caused by a reduced CD25 promoter/enhancer activity in c-Rel−/− cells. Regardless of the mechanism of reduced CD25 expression, our demonstration that c-Rel regulates iTreg development independent of IL-2 (the ligand for CD25) indicates that the c-Rel–Foxp3 axis is crucial for the generation of Treg cells.

Since many immunosuppressive drugs currently used for treating inflammatory diseases inhibit the Rel/NF-κB pathway, they may also inadvertently block Treg differentiation. However, because c-Rel is also required for humoral immunity and Th1 (but not Th2) cell-mediated immunity (Hilliard et al., 2002; Tumang et al., 1998), c-Rel inhibition or deficiency alone may not lead to enhanced autoimmunity. Thus, results reported here not only help advance our understanding of the Treg differentiation program, but also aid in developing new drugs for combating inflammatory diseases.

Experimental Procedures

Mice

C57BL/6 (B6) mice that carry a c-Rel gene null mutation were generated as described, and were backcrossed to B6 mice for 12 generations before used in this study (Hilliard et al., 2002; Liou et al., 1999). B6, CD45.1+ B6, B6;129, RelB-deficient B6, NF-κB1-deficient B6;129, and RAG-1-deficient B6 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA). All mice were housed in the University of Pennsylvania animal care facilities under pathogen-free conditions and all procedures were pre-approved by the institutional animal care and use committee.

Generation of bone marrow chimeras

Bone marrow cells were isolated from WT and c-Rel−/− C57BL/6 mice that express either CD45.1 or CD45.2, and were depleted of T cells with biotin–anti-TCRβ (H57-597; BD Pharmingen) and streptavidin-labeled magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec). For one of the bone marrow chimeras, WT bone marrow cells from CD45.1+ C57BL/6 mice were mixed with either WT or c-Rel−/− CD45.2+ bone marrow cells at a ratio of 4:1 (CD45.1+:CD45.2+). For another chimera, bone marrow cells from WT CD45.1+ C57BL/6 mice were mixed with c-Rel−/− CD45.2+ bone marrow cells at a ratio of 1:1 (CD45.1+:CD45.2+). Bone marrow cells, 10–15 million per recipient, were transferred by intravenous injection into sub-lethally irradiated (500 rads, two times spaced three hours apart) C57BL/6 mice. Seven weeks later, mice were sacrificed, and the Foxp3 expression in T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Antibodies and flow cytometry

Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-Foxp3 and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-IL-17A were purchased from BD Pharmingen. PE-conjugated anti-CD4, cyanine-5-conjugated anti-CD8, and allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD25 were purchased from Caltag laboratories. Flow cytometric analyses were performed on freshly isolated thymocytes and splenocytes, and cultured T cells. For intracellular staining, cells were fixed in Fixation/Permeabilization solution (BD Biosciences) and treated with specific antibodies per manufacturer’s protocols. Stained cells were analyzed on a FACS-Calibur (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed with the FlowJo software.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP was performed using the ChIP assay kit, per the manufacturer’s instructions (Upstate Biotechnology). Briefly, cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min and lysed in the lysis buffer. DNA was then fragmented by sonication. After pre-clearance for 1 h at 4°C with salmon sperm DNA-saturated protein A-agarose, chromatin solutions were immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C using 1 μg of rabbit antibodies to c-Rel, p65, NFATc2, pCREB (Santa Cruz Biotechology, Inc.), or Smad3 (Abcam), or control rabbit IgG. Input and immunoprecipitated chromatins were incubated for 4 h at 65°C to reverse cross-links. After proteinase K digestion, DNA was extracted with phenol/chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. ChIP DNA was then analyzed by PCR using the following primer sets: Foxp3-promoter-forward: 5′-CTTCCCATTCACATGGCAGGC-3′; Foxp3-promoter-reverse: 5′-TTGCCCTTTACGAGTCATCTG-3′. Enhancer-1-forward: 5′-CCCATGTTGGCTTCCAGTCTCCTTTATGG-3′; enhancer-1-reverse: 5′-AGGTACAGAGAGGTTAAGAGCCTGGGT-3′. Enhancer-2-forward: 5′-TGTGACAACAGGGCCCAGAT-3′; enhancer-2-reverse: 5′-GCGTTCCTGTTTGACTGTTTCTT-3′. The PCR products, which correspond to nucleotides −501 to −236 of the promoter, +2,093 to +2,248 of enhancer-1, and +4,495 to +4,595 of enhancer-2, respectively, were analyzed by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels.

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using oligo dT primers. Real-time PCR was carried out in an Applied Biosystems 7500 system using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Relative levels of gene expression was determined using GAPDH as the control. The following primers were used to amplify mouse Foxp3 gene: forward, 5′-CAGCTGCCTACAGTGCCCCTAG-3′; reverse, 5′-CATTTGCCAGCAGTGGGTAG-3′.

Nucleotide pull-down assay

EL4/LAF cells (Tone et al., 2008) were stimulated with 50 ng/ml PMA (Sigma) and 1 μM ionomycin (Sigma) for 6 h at 37°C. The cells were re-suspended in lysis buffer 1 mM DTT, and 0.1% (20 mM HEPES, 420 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, Nonidet P-40) with protease inhibitors, and incubated on ice for 15 min. Insoluble materials were removed by centrifugation. 100 μg lysate protein was diluted with dilution buffer (which is same as lysis buffer, but without NaCl) and incubated with 10 μg of poly(deoxyinosinic-deoxycytidylic acid) (Roche) and 50 μl of streptavidin-agarose beads (Sigma) carrying biotinylated oligonucleotides (as described below) for 3 h at 4°C. The beads were washed twice with dilution buffer, resuspended in 50 μl 2X SDS sample loading buffer (BioRad), and heated to 95°C for 10 min. The eluants were resolved by SDS-PAGE. c-Rel and NFATc2 molecules were detected by immunoblotting with specific antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The oligonucleotides containing either the wild type or mutated Rel/NFAT binding sites used in this study are: Foxp3-NFATc2-382, 5′-TTGTGATTTGACTTATTTTCCCTCAGTTTTTTT-3′; Foxp3-NFATc2-382-mutant: 5′-TTGTGATTTGACTTATTTGGACTCAGTTTTTTT-3′; Foxp3-NFATc2-327, 5′-TTTAAGAAATTGTGGTTTCTCATGAGCCCTGTT-3′; Foxp3-NFATc2-327-mutant: 5′-TTTAAGAAATTGTGGTTTCTCATGAGCCCTGTT-3′.

Promoter luciferase assay

The pGL4-based constructs containing the 1.88 kb fragment of the murine Foxp3 promoter or promoter deletion mutants were described previously (Tone et al., 2008). Site-directed mutagenesis of Rel/NFAT binding site was performed using the QuickChange kit (Stratagene), according to manufacturer’s instructions. DNA sequencing was used to confirm the mutated nucleotides. EL4/LAF cells (Tone et al., 2008) were transfected with reporter constructs together with c-Rel-, p65-, p50- or RelB-expression vector or empty vector using Lipofectamine LTX reagent (Invitrogen). After 24 hours, cells were treated with or without 50 ng/ml PMA and 1 μM ionomycin for 4–5 hours and the luciferase activities of whole cell lysates were analyzed using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). Co-transfection with the Renilla-luciferase expression vector pRL-TK (Promega) was performed in all reporter assays. For all samples, the assays were repeated at least three times and the data were normalized for transfection efficiency by dividing firefly luciferase activity by that of the Renilla luciferase.

Regulatory T cell differentiation

Splenic CD4+CD8− CD25− T cells were purified by magnetic cell sorting (MACS) (Miltenyi Biotec), and cultured at 1.5 × 106/well in 24-well plates pre-coated with anti-CD3 (5 μg/ml), in the presence of 1 μg/ml anti-CD28, 1 μg/ml anti-IL-4, 1 μg/ml anti-IFN-γ, and 5 ng/ml TGF-β1, with or without 50 U/ml recombinant mouse IL-2 or 1 μg/ml purified anti-mouse IL-2. Three days later, cells were washed, and treated for 4–5 hr with 50 ng/ml PMA and 1 μM ionomycin in the presence of GolgiStop (1:1500 dilution, BD Pharmingen) at 37°C before being examined by flow cytometry.

Statistical analyses

X2 analysis was used to evaluate the statistical significance of the differences in the percentages of cells, and Student’s t test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of mRNA, protein, and promoter activities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Ruaidhri Carmody, Wanjun Chen, and Shunyou Gong for valuable discussions, and Ms. Jennifer DeVirgiliis for technical support. Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI50059, DK070691 and AI069289), USA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barnes PJ, Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;336:1066–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron U, Floess S, Wieczorek G, Baumann K, Grutzkau A, Dong J, Thiel A, Boeld TJ, Hoffmann P, Edinger M, et al. DNA demethylation in the human FOXP3 locus discriminates regulatory T cells from activated FOXP3(+) conventional T cells. European Journal of Immunology. 2007;37:2378–2389. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg AA, Baltimore D. An essential role for NF-kappaB in preventing TNF-alpha-induced cell death. Science. 1996;274:782–784. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett CL, Christie J, Ramsdell F, Brunkow ME, Ferguson PJ, Whitesell L, Kelly TE, Saulsbury FT, Chance PF, Ochs HD. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat Genet. 2001;27:20–21. doi: 10.1038/83713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommireddy R, Doetschman T. TGFbeta1 and Treg cells: alliance for tolerance. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2007;13:492–501. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondarenko VA, Liu YV, Jiang YI, Studitsky VM. Communication over a large distance: enhancers and insulators. Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2003;81:241–251. doi: 10.1139/o03-051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp T, Palmetshofer A, Serfling E, Heib V, Schmitt S, Richter C, Klein M, Schild H, Schmitt E, Stassen M. NFATc2 and NFATc3 transcription factors play a crucial role in suppression of CD4+ T lymphocytes by CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;201:181–187. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell E, Mathieson B, Young HA, Keller J, Ihle JN, Rice NR. Detection of c-rel-related transcripts in mouse hematopoietic tissues, fractionated lymphocyte populations, and cell lines. Molecular & Cellular Biology. 1987;7:1304–1309. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.3.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkly L, Hession C, Ogata L, Reilly C, Marconi LA, Olson D, Tizard R, Cate R, Lo D. Expression of relB is required for the development of thymic medulla and dendritic cells. Nature. 1995;373:531–536. doi: 10.1038/373531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, Lei KJ, Li L, Marinos N, McGrady G, Wahl SM. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25− naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2003;198:1875–1886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Kuchroo VK, Inobe J, Hafler DA, Weiner HL. Regulatory T cell clones induced by oral tolerance: suppression of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Science. 1994;265:1237–1240. doi: 10.1126/science.7520605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenot JD, Dooley JL, Farr AG, Rudensky AY. Developmental regulation of Foxp3 expression during ontogeny. J Exp Med. 2005a;202:901–906. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Williams LM, Dooley JL, Farr AG, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity. 2005b;22:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenot JD, Rudensky AY. A well adapted regulatory contrivance: regulatory T cell development and the forkhead family transcription factor Foxp3. Nature Immunology. 2005;6:331–337. doi: 10.1038/ni1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerondakis S, Grumont R, Rourke I, Grossmann M. The regulation and roles of Rel/NF-kappa B transcription factors during lymphocyte activation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:353–359. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey VL, Wilkinson JE, Rinchik EM, Russell LB. Fatal lymphoreticular disease in the scurfy (sf) mouse requires T cells that mature in a sf thymic environment: potential model for thymic education. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:5528–5532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard B, Mason N, Xu L, Sun J, Lamhamedi-Cherradi SE, Liou HC, Hunter C, Chen Y. Critical Roles of c-Rel in Autoimmune Inflammation and Helper T Cell Differentiation. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;110:843–850. doi: 10.1172/JCI15254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huguet C, Bouali F, Enrietto PJ, Stehelin D, Vandenbunder B, Abbadie C. The avian transcription factor c-Rel is expressed in lymphocyte precursor cells and antigen-presenting cells during thymus development. Developmental Immunology. 1998;5:247–261. doi: 10.1155/1998/58608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson PC, Winerdal ME, Marits P, Thorn M, Ohlsson R, Winqvist O. FOXP3 promoter demethylation reveals the committed Treg population in humans. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khattri R, Cox T, Yasayko SA, Ramsdell F. An essential role for Scurfin in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:337–342. doi: 10.1038/ni909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH. Migration and function of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in the hematolymphoid system. Experimental Hematology. 2006;34:1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HP, Leonard WJ. CREB/ATF-dependent T cell receptor-induced FoxP3 gene expression: a role for DNA methylation. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204:1543–1551. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JM, Rudensky A. The role of the transcription factor Foxp3 in the development of regulatory T cells. Immunological Reviews. 2006;212:86–98. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretschmer K, Apostolou I, Jaeckel E, Khazaie K, von Boehmer H. Making regulatory T cells with defined antigen specificity: role in autoimmunity and cancer. Immunological Reviews. 2006;212:163–169. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal G, Zhang N, van der Touw W, Ding Y, Ju W, Bottinger E, Reid P, Levy D, Bromberg J. Epigenetic Regulation of Foxp3 Expression in Regulatory T Cells by DNA Methylation. Journal of Immunology. 2009;182:259–273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S, Alard P, Zhao Y, Parnell S, Clark SL, Kosiewicz MM. Conversion of CD4+ CD25− cells into CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in vivo requires B7 costimulation, but not the thymus. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;201:127–137. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou HC, Jin Z, Tumang J, Andjelic S, Smith KA, Liou ML. c-Rel is crucial for lymphocyte proliferation but dispensable for T cell effector function. International Immunology. 1999;11:361–371. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhang P, Li J, Kulkarni AB, Perruche S, Chen W. A critical function for TGF-beta signaling in the development of natural CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Nature Immunology. 2008;9:632–640. doi: 10.1038/ni.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr J, Knoechel B, Abbas AK. Regulatory T cells in the periphery. Immunological Reviews. 2006;212:149–162. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Tian L, Han Y, Vogelbaum M, Stark GR. Dose-dependent cross-talk between the transforming growth factor-beta and interleukin-1 signaling pathways. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:4365–4370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700118104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel PY, Ouaked N, Ruckert B, Karagiannidis C, Welz R, Blaser K, Schmidt-Weber CB. Molecular mechanisms underlying FOXP3 induction in human T cells. Journal of Immunology. 2006;176:3593–3602. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merika M, Thanos D. Enhanceosomes. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2001;11:205–208. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Garra A, Vieira P. Regulatory T cells and mechanisms of immune system control. Nat Med. 2004;10:801–805. doi: 10.1038/nm0804-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh-Hora M, Yamashita M, Hogan PG, Sharma S, Lamperti E, Chung W, Prakriya M, Feske S, Rao A. Dual functions for the endoplasmic reticulum calcium sensors STIM1 and STIM2 in T cell activation and tolerance. Nature Immunology. 2008;9:432–443. doi: 10.1038/ni1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polansky JK, Kretschmer K, Freyer J, Floess S, Garbe A, Baron U, Olek S, Hamann A, von Boehmer H, Huehn J. DNA methylation controls Foxp3 gene expression. European Journal of Immunology. 2008;38:1654–1663. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao A, Luo C, Hogan PG. Transcription factors of the NFAT family: regulation and function. Annual Review of Immunology. 1997;15:707–747. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nature Immunology. 2005;6:345–352. doi: 10.1038/ni1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S, Ono M, Setoguchi R, Yagi H, Hori S, Fehervari Z, Shimizu J, Takahashi T, Nomura T. Foxp3+ CD25+ CD4+ natural regulatory T cells in dominant self-tolerance and autoimmune disease. Immunological Reviews. 2006;212:8–27. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Supprian M, Courtois G, Tian J, Coyle AJ, Israel A, Rajewsky K, Pasparakis M. Mature T cells depend on signaling through the IKK complex. Immunity. 2003;19:377–389. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevach EM. From vanilla to 28 flavors: multiple varieties of T regulatory cells. Immunity. 2006;25:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevach EM, DiPaolo RA, Andersson J, Zhao DM, Stephens GL, Thornton AM. The lifestyle of naturally occurring CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Immunological Reviews. 2006;212:60–73. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simek S, Rice NR. Detection and characterization of the protein encoded by the chicken c-rel protooncogene. Oncogene Research. 1988;2:103–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriskantharajah S, Belich M, Papoutsopoulou S, Janzen J, Tybulewicz V, Seddon B, Ley S. Proteolysis of NF-kappaB1 p105 is essential for T cell antigen receptor–induced proliferation. Nature Immunology. 2008 doi: 10.1038/ni.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q, Henriksen KJ, Boden EK, Tooley AJ, Ye J, Subudhi SK, Zheng XX, Strom TB, Bluestone JA. Cutting edge: CD28 controls peripheral homeostasis of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Journal of Immunology. 2003;171:3348–3352. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tommasini A, Ferrari S, Moratto D, Badolato R, Boniotto M, Pirulli D, Notarangelo LD, Andolina M. X-chromosome inactivation analysis in a female carrier of FOXP3 mutation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;130:127–130. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01940.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tone Y, Furuuchi K, Kojima Y, Tykocinski ML, Greene MI, Tone M. Smad3 and NFAT cooperate to induce Foxp3 expression through its enhancer. Nature Immunology. 2008;9:194–202. doi: 10.1038/ni1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumang JR, Owyang A, Andjelic S, Jin Z, Hardy RR, Liou ML, Liou HC. c-Rel is essential for B lymphocyte survival and cell cycle progression. European Journal of Immunology. 1998;28:4299–4312. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199812)28:12<4299::AID-IMMU4299>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Tam WF, Hughes CC, Rath S, Sen R. c-Rel is a target of pentoxifylline-mediated inhibition of T lymphocyte activation. Immunity. 1997;6:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Vig M, Lyons J, Van Parijs L, Beg AA. Combined deficiency of p50 and cRel in CD4+ T cells reveals an essential requirement for nuclear factor kappaB in regulating mature T cell survival and in vivo function. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2003;197:861–874. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler SF. FOXP3: of mice and men. Annual Review of Immunology. 2006;24:209–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.