Abstract

Purpose

Several different multivariate prediction models using routine clinical variables or multi-gene signatures have been proposed to predict pathologic complete response to combination chemotherapy in breast cancer. Our goal was to compare the performance of four conceptually different predictors in an independent cohort of patients.

Experimental Design

Gene expression profiling was performed on fine needle aspirations of 100 stage I-III breast cancers prior to preoperative paclitaxel, 5-FU, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide combination chemotherapy. Pathologic response was correlated with prediction results from a clinical nomogram, a human cancer-derived genomic predictor (DLDA30), a cell line-based genomic predictor (in vitro-COXEN), and an optimized cell line-derived (in vivo-COXEN) predictor. None of the 100 test cases were used in the development of these predictors.

Results

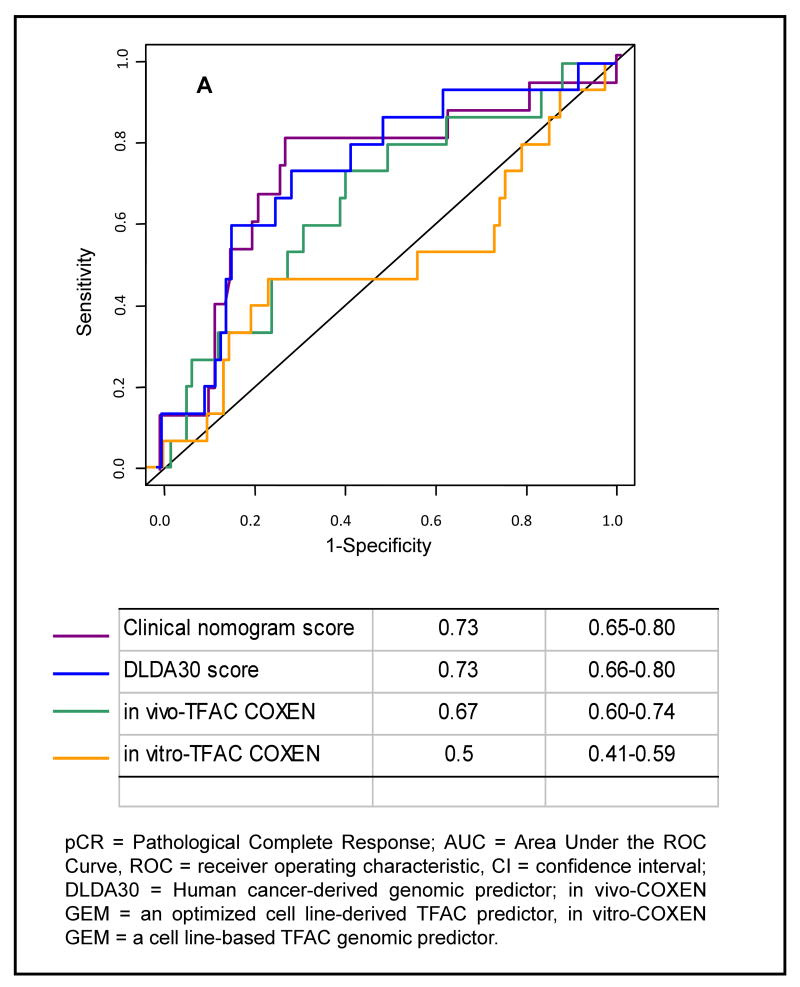

The in vitro-COXEN using a combination of 4 individual drug sensitivity predictions derived from cell lines was not predictive, AUC:0.5 (95%CI: 0.41-0.59). The clinical nomogram (AUC: 0.73, 95%CI: 0.65-0.80) and the DLDA30 (AUC: 0.73, 95%CI [0.66-0.80]) genomic predictor had similar performances. The in vivo-COXEN that used informative genes from cell lines but was trained on a separate human data set also showed significant predictive value, AUC: 0.67 (95%CI: 0.60-0.74). These 3 different prediction scores correlated with each other and were significant in univariate but not in multivariate analysis.

Conclusions

Three conceptually different predictors performed similarly in this validation study and tended to identify the same patients as responders. A genomic predictor that relied solely on a composite of individual drug sensitivity predictions from cell lines did not show any predictive value.

Keywords: Combination Chemotherapy, Co-expression Extrapolation (COXEN), Multi-gene Expression-based Prediction Models

Introduction

Not all patients with breast cancer respond to chemotherapy and different drugs induce different responses in different patients. Therefore, molecular predictors that identify who may benefit from what drug with sufficient accuracy could aid treatment selection. Accurate response predictors could also streamline drug development and facilitate the conduct of clinical trials through the identification of patients who do or do not benefit from existing therapies. Several investigators suggested that cell line-derived predictors are useful to predict response to chemotherapy in patients.(1, 2) A commonly used strategy is to use gene expression data and in vitro drug response information from the NCI-60 or other cell line panels and use these information to develop drug-specific pharmacogenomic response predictors than can be applied to human data.(3-5) It is also possible to develop multi-gene predictors of response to therapy from supervised analysis of gene expression data using human cancers with known response to chemotherapy.(6, 7) Many routinely available clinical variables are also associated with chemotherapy sensitivity in breast cancer. Estrogen-receptor (ER)-negative, high grade and HER2-positive cancers all tend to show greater sensitivity to chemotherapy and these variables can also be combined into a fairly accurate multivariate prediction model.(8)

The goal of the current study was to compare the predictive accuracy of 4 conceptually different predictors. Each predictor was applied to the same 100 cases of breast cancers that received uniform preoperative chemotherapy and were not included in the predictor development process. Each of these cases received neoadjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel followed by 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and cyclophophosphamide (T/FAC) and pathologic response was assessed. The four predictors included; (i) a clinical variable-based nomogram to predict pathologic complete response (pCR)(8) (ii) a 30-probe set pharmacogenomic predictor that was developed from the supervised analysis of 81 breast cancers that received T/FAC preoperative chemotherapy(7), (iii) a cell line-derived response marker that combined individual drug-specific predictive signatures from the NCI 60 cell line data(1) and (iv) a revised cell line-derived predictor that used human gene expression data to train a prediction model that used drug-specific sensitivity features selected from the cell lines. Each of these predictors was finalized before application to the current validation data set.

Methods

Patients and Materials

Gene expression data from 100 stage I-III breast cancers were generated at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC). These patients were prospectively and sequentially accrued to a pharmacogenomic marker discovery trial. None of these cases were included in the development process of any of the 4 predictors. Gene expression profiling was performed on fine needle aspiration specimens of newly-diagnosed breast cancers before any therapy. These specimens contain 70-90% neoplastic cells with minimal stromal contamination.(9) All patients signed informed consent for genomic analysis of their cancer. Patients received 6 months' preoperative T/FAC chemotherapy followed by surgical resection of the cancer. No patient received preoperative trastuzumab in this study. The clinical characteristics of the patient population are presented in Table 1. Response to chemotherapy was dichotomized as pathologic complete response (pCR = no residual invasive cancer in the breast and lymph nodes) or residual invasive cancer (RD). The prognostic importance of pCR has extensively been discussed in the literature.(10, 11)

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Clinical and pathological data | Validation set (n=100) |

|---|---|

| Median age, years | 50 (26-76) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 68 |

| African American | 12 |

| Asian | 7 |

| Hispanic | 13 |

| Histological type | |

| Invasive ductal | 85 |

| Mixed ductal / Lobular | 8 |

| Invasive lobular | 7 |

| Pre-chemotherapy tumor size | |

| T0 (with positive axillary node) | 2 |

| T1 | 8 |

| T2 | 62 |

| T3 | 13 |

| T4 | 15 |

| Clinical N stage | |

| N0 | 27 |

| N1 | 47 |

| N2 | 13 |

| N3 | 13 |

| Nuclear grade | |

| 1 | 11 |

| 2 | 42 |

| 3 | 47 |

| Estrogen Receptor status1 | |

| Positive | 60 |

| Negative | 40 |

| HER-2 status2 | |

| Positive | 7 |

| Negative | 93 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy3 | |

| Weekly T × 12 + FAC × 4 | 98 |

| 3-weekly T × 12 + FAC × 4 | 2 |

| Pathological complete response | 15 |

| Residual disease | 85 |

Cases where >10% of tumor cells stained positive for ER with immunohistochemistry (IHC) were considered positive.

Cases that showed either 3+ IHC staining or had gene copy number >2.0 were considered HER-2 “positive”.

T= paclitaxel, FAC = 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide.

Gene expression profiling

RNA extraction and gene expression profiling were performed in multiple batches over time as described previously.(7) Normalization and quality control assessment of the hybridization results were performed with SimpleAffy software of the Bioconductor packagei (Supplementary Methods). All CEL files are available at the GEO website accession number GSE16716 Microarray Quality Control Consortium II data set.

Statistical analysis

The clinical variable-based nomogram to estimate the probability of pCR was applied as it was described in the original publication.(8) It is also available as a free web-based toolii. The overall development and validation schema for the 3 genomic predictors is illustrated in Supplementary Figure 1. The DLDA30 predictor employs diagonal linear discriminant analysis (DLDA) to calculate a prediction score based on the expression of 30 probe sets that are differentially expressed between cases with pCR and RD to neoadjuvant T/FAC chemotherapy.(7) This predictor was trained and the threshold defined on a discovery set of 82 cases. For this analysis, the current gene expression data was normalized using dCHIP V1.3 software and the same code was used to perform prediction estimates as described in the original publicationiii.

The in vitro-COXEN GEM prediction model was derived from microarray data and in vitro drug sensitivity results.(1) Informative probe sets that were associated with paclitaxel, 5-fluoruracil, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide sensitivity, respectively were identified from the NCI-60 microarray data. The 10-20% most and least sensitive cell lines based on GI-50 values were compared to define the informative probe sets that were further filtered based on the COXEN coefficient which represents the degree of concordance of expression between cell line and human breast cancer gene expression data.(12) Genes with the highest COXEN coefficient were included in the drug-specific prediction models that employed linear discriminant analysis (LDA) and were trained on the NCI-60 cell lines.(13, 14) A combined score from the 4 individual drug predictors, assuming their independence, was calculated to generate a combination chemotherapy (T/FAC) predictor (see Supplementary Methods). The higher the COXEN score the higher the predicted probability to achieve response to a given drug or combination.

The in vivo-COXEN GEMs were developed using the same informative probe sets for each drug as used in the in vitro-COXEN GEM described above. However, the LDA classification model for the in vivo-COXEN GEM was trained on a publicly available human data set that was used to develop and validate the original DLDA30 model (n=133).(7) The main difference between the in vivo-COXEN GEM strategy and the strategy that lead to the development of the DLDA30 is that the informative features for the in vivo-COXEN GEM were derived from cell lines and may represent drug-specific sensitivity markers, whereas the features for DLDA30 were derived from the human data. The performance of the in vitro- and in vivo-COXEN GEM was evaluated on the 100 new cases blindly. Prediction scores were calculated from the CEL file information provided to the team at University of Virginia without knowledge of response outcome. The prediction scores were returned to investigators at UT MDACC to determine correlation with response.

Predictor performances are described using standard metrics including area under the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity and positive (PPV) and negative (NPV) predictive values. In order to calculate misclassification error rates we defined the best predictor for each method using the Youden point on the ROC curve. The Youden index (YI) is defined as maximum (sensitivity (YP) + specificity (YP) -1), occurring at the optimum threshold which is the Youden point (YP) (15). The YP corresponds to the point on the ROC curve that is farthest from chance and defines predictor thresholds that maximize both the sensitivity and the specificity and minimize misclassification rate in a given data set. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV for the COXEN GEM predictors were calculated based on this optimized cut off that was defined in an external reference set of 133 cases.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression on pCR/RD status were performed to determine which routine clinical variables and prediction scores were associated significantly with pCR. The routine clinical variables used were patient age, pre-treatment tumor size, lymph node status, nuclear grade, ER status and HER2 status. Patient age, nuclear grade and all prediction scores were treated as continuous variables. Since some of the prediction scores were a combination of the clinical variables (e.g., the clinical nomogram score), multivariate logistic regression using only the prediction scores were also performed. Backward elimination was performed during the multivariate regression analysis with a significance level of 0.05 for a covariate to stay in model. In order to make comparable the odds ratios (OR) across the four predictors, we standardize the four score to a similar scale from 0 to 10.

Results

Prediction performance of the clinical nomogram

We calculated for each patient the probability of pCR using the clinical nomogram and compared the predicted pCR rates to the observed rates. Discrimination (i.e., whether the relative ranking of individual predictions is in the correct order) was quantified with the AUC.(16) Fifteen of the 100 patients had pCR. This is less than what has been observed in the past in a larger series of patients who received the same preoperative chemotherapy.(17) The lower pCR rate in this patient cohort is likely due to the relative absence of HER-2 positive patients, only 7% of cases were HER2-positive in this series compared to the typical 20-25% seen in the general population and in the previous study. HER2-positive breast cancers have significantly higher rates of pCR compared to HER2-normal cancers.(18) Their absence from this more recent patient cohort is due to changing clinical practice; in recent years many HER-2 positive cases received trastuzumab concomitant with chemotherapy in our center.(19) Despite this difference in patient population, the clinical variable-based prediction showed good discrimination. The AUC for the clinical nomogram was 0.72 (95% CI: 0.65-0.78) which is similar to the AUC (0.79) observed in the validation cohort reported in the original publication.(8) The ROC curves for the nomogram, DLDA30, in vivo-T/FAC COXEN GEM, and in vitro-TFAC COXEN GEM are plotted on Figure 1.

Figure 1. Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curve analysis of the four conceptually different chemotherapy response predictors.

ROC curves are shown for the clinical nomogram, the DLDA30 predictor, the in vitro combined T/FAC COXEN GEM and the in vivo combined T/FAC COXEN GEM.

We also assessed calibration that measures agreement between observed outcome frequencies and predicted probabilities of response (Supplementary Figure 2).(16) Calibration was less good than previously reported; we observed a significant difference between the predicted probabilities and the observed frequencies. The average difference and maximal differences in prediction and observations were 12% and 33%, respectively (p=0.006) and showed that the nomogram tended to err towards overestimating the probability of pCR.

Prediction Performance of the DLDA30

The 31-gene pharmacogenomic predictor had an AUC of 0.73 (95% CI: 0.65-0.80) (Figure 1). Using the previously established threshold, the overall accuracy was 72% (95%CI: 62-81), the sensitivity 60% (95%CI: 32-84), specificity 74% (95%CI: 63-83), the PPV 29% (95%CI: 14-48) and the NPV 91% (95%CI: 82-97). These values are similar but generally lower than observed in the previous small validation study (n= 51 AUC = 0.88).(7) The difference in predictive performance is likely due to the relative absence of HER2-positive cases in this study. The calibration of the DLDA30 was excellent (Supplementary Figure 2).

Prediction performance of the cell line-derived COXEN GEM predictors

We compared the in vitro-COXEN GEM chemo-sensitivity scores between cases with pCR and residual cancer for each drug separately and also in combination. The genes selected as informative for response to individual drugs from the NCI 60 cell lines showed no overlap with the genes included in the DLDA30 predictor (Supplementary Table 1). Mean COXEN GEM scores for each drug and the combined score are shown in Table 2. AUC for the combined score is plotted on Figure 1. The results indicate that for 3 out of the 4 drugs, the purely cell line-derived predictor could not discriminate response in human patients. However, the AUC for the single agent paclitaxel predictor was significantly better than random (AUC:0.64, 95 CI%: 0.56-0.72). It showed a sensitivity of 60% (95% CI: 35-85), specificity 65% (95% CI:55-75), PPV 23% (95% CI:10-36), and NPV 90% (95% CI:83-98) at the cutoff value which was predetermined on a previous patient set treated with similar chemotherapy by maximizing the Youden index.

Table 2. Comparison of mean COXEN GEM chemotherapy sensitivity scores for individual drugs and for their combination between patients with pathologic complete response (pCR) and residual cancer.

*TFAC = sum of individual paclitaxel, 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide scores. Significant results are highlighted in bold.

| Predictor | Drug | pCR group GEM Scores (mean +/- 95% CI) |

Residual Cancer GEM Score (mean +/- 95% CI) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paclitaxel | 0.531+/-0.225 | 0.289+/-0.079 | 0.045 | |

| In vitro | 5-fluorouracil | 0.447+/-0.229 | 0.426+/-0.074 | 0.848 |

| COXEN | Doxorubicin | 0.168+/-0.170 | 0.235+/-0.078 | 0.459 |

| GEM | Cyclophosphamide | 0.146+/-0.176 | 0.160+/-0.061 | 0.879 |

| TFAC | 0.659+/-0.192 | 0.601+/-0.075 | 0.562 | |

| Paclitaxel | 0.449+/-0.172 | 0.221+/-0.048 | 0.015 | |

| In vivo | 5-fluorouracil | 0.262+/-0.057 | 0.254+/-0.023 | 0.787 |

| COXEN | Doxorubicin | 0.365+/-0.098 | 0.239+/-0.037 | 0.019 |

| GEM | Cyclophosphamide | 0.366+/-0.135 | 0.251+/-0.049 | 0.106 |

| TFAC | 0.755+/-0.133 | 0.595+/-0.052 | 0.028 | |

Next, we tested the in vivo-COXEN GEM predictors that were trained on a separate T/FAC-treated patient cohort of 133 cases. The single drug predictors for both paclitaxel (p=0.015) and doxorubicin (p=0.019) had significantly higher mean scores in the pCR cohort but the scores for 5-fluorouracil and cyclophosphamide were not significantly different between the two response groups (Table 2). The combined 4-drug in vitro-T/FAC COXEN GEM score also remained significant (p=0.028). The AUCs for the paclitaxel and doxorubicin predictors were 0.64 (95%CI: 0.56-0.71) and 0.71 (95%CI: 0.64-0.78), respectively. The combined T/FAC in vivo-COXEN GEM had an AUC of 0.67 (95%CI: 0.60-0.74, p<0.04) (Figure 1). However, the calibration of the T/FAC in vivo-COXEN GEM was poor indicating that this predictor overestimated the probability of pCR (Supplementary Figure 1).

The misclassification error rates (MER), at the Youden point of the ROC, were 0.27 (95% CI: 0.232-0.339) for both the clinical nomogram and the DLDA30 predictor. The MER were 0.38 (95% CI: 0.334-0.45) and 0.35 (95% CI: 0.285-0.412) for the in vivo- and in vitro-COXEN, respectively. In summary, these results indicate that genes identified in cell lines as predictors of response to certain drugs can carry information about response in human cancers. The results also show that this is not true for all drugs and that training of the model, assigning predictive weights to the informative genes, is best done on human cancers with known response rather than on the cell lines from which the informative features were defined.

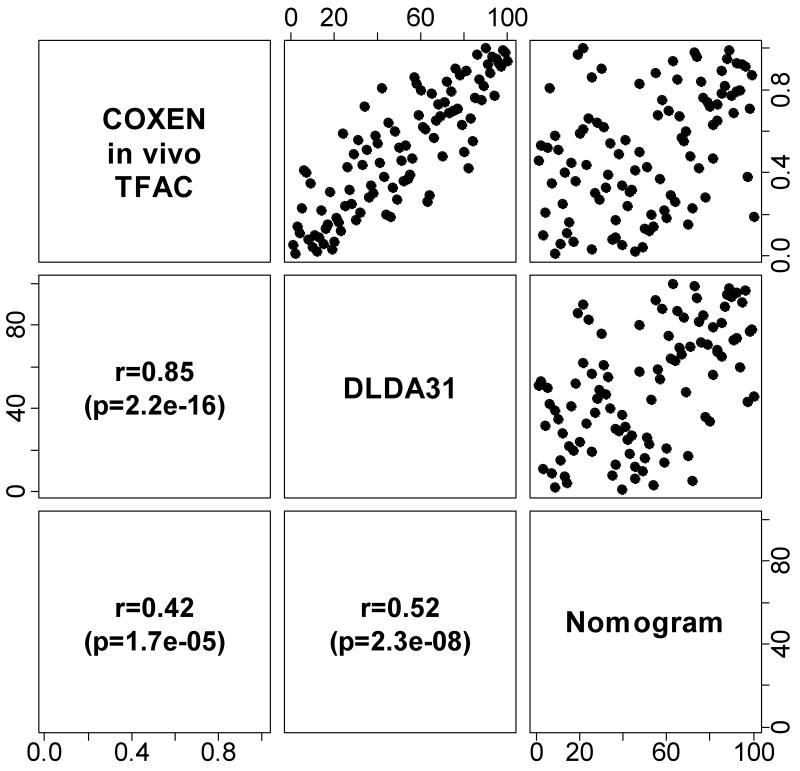

Correlation between prediction scores

Since all predictors were applied to the same 100 cases, we could examine the correlation between prediction scores. In this analysis we only examined the 3 predictors that showed significant discriminating value in the human validation data. Since the clinical nomogram, the DLDA30, and the in vivo T/FAC COXEN GEM scores each represent different scales their correlation was plotted based on rank. There was a good correlation (r=0.85) between how the two genomic scores ranked individual patients by predicted sensitivity (Figure 2). The rank correlation was somewhat less but still significant for the nomogram and the genomic predictors. These observations suggest that the various predictors place individuals in the same position in a relative sensitivity scale even if they measure different variables.

Figure 2. Correlation between ranks of prediction scores.

Ranks of predicted scores of the in vivo-GEM, DLDA30 predictor and clinical nomogram were plotted against each other. Rank-based Spearman correlation and p-value were calculated for each pair of comparisons.

The result of univariate logistic regression showed that nuclear grade, ER and HER-2 status, clinical nomogram, DLDA30 and in vivo-T/FAC COXEN GEM scores were each significantly associated with pCR status (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis using both clinical variables and prediction scores, none of these remained significant (Table 3) indicating that the various scores identify similar populations. After backward elimination of non-significant covariates, only ER status remained significantly associated with pCR status. In the multivariate analysis using just the three significant prediction scores, clinical nomogram, DLDA30 and in vivo-T/FAC COXEN GEM scores, only the clinical nomogram score remained significant after backward elimination.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression results including clinical and genomic score variables.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age | 1.01 (0.95-1.06) | 0.82 | 0.98 (0.90-1.06) | 0.61 |

| Pre-chemotherapy T size (2-4 vs 0-1) | 0.68 (0.13-3.54) | 0.64 | 0.85 (0.06-12.14) | 0.91 |

| Clinical N stage (N1-3 vs N0) | 6.17 (0.77-49.41) | 0.087 | 2.99 (0.28-31.40) | 0.36 |

| Nuclear grade | 5.06 (1.44-17.80) | 0.011 | 1.97 (0.34-11.49) | 0.45 |

| ER status (positive vs negative) | 0.07 (0.02-0.34) | 0.00091 | 0.20 (0.02-1.87) | 0.16 |

| HER-2 status (positive vs negative) | 9.94 (1.96-50.42) | 0.0056 | 4.45 (0.52-38.14) | 0.17 |

| Clinical nomogram score | 1.49 (1.16-1.90) | 0.0016 | 0.98 (0.64-1.49) | 0.91 |

| DLDA30 score | 1.52 (1.13-2.04) | 0.0055 | 1.29 (0.69-2.39) | 0.42 |

| in vivo-T/FAC COXEN GEM score | 1.40 (1.03-1.90) | 0.034 | 1.05 (0.50-2.20) | 0.90 |

| in vitro-T/FAC COXEN GEM score | 0.95 (0.81-1.13) | 0.59 | 0.83 (0.63-1.90) | 0.18 |

OR = Odds ratio for having pCR vs. RD; 95% CI = confidence interval, ER status was determined by immunohistochemistry and HER2 status was determined by immunohistochemistry or FISH (Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization). Predictor scores, age and nuclear grade were used as continuous variables.

Discussion

Different subsets of breast cancers have different degrees of chemotherapy sensitivity and it is increasingly apparent that there are several methods that can estimate someone's probability of response to therapy. Estrogen receptor-negative, high grade, and HER2-positive cancers have significantly higher rates of response to chemotherapy than other breast cancers, therefore these clinical variables can be combined to yield a multivariate prediction model. Identification of gene expression differences between responding and non-responding cases can also yield multi-gene predictors to commonly used combination chemotherapy regimens. However, these models are not treatment or regimen specific. A theoretically appealing approach is to develop gene expression-based predictors from cell line models in the laboratory. This strategy offers a promise for individual drug-specific predictors that could be combined into multi-drug predictors that could be used to select the optimal combination chemotherapy for an individual in the clinic. This approach has also yielded promising results but it is not without controversy (20-22). The current study represents a prospective evaluation of 4 conceptually different previously established predictors of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The results show that both a clinical variable-based model and a genomic predictor developed through supervised analysis of human gene expression data could discriminate between cases with higher and lower probability to achieve pCR to T/FAC chemotherapy. However, both predictors had lesser performance than seen in the original reports that is partly due to a shift in patient population used for this validation study. This illustrates an inherent challenge to clinical biomarker development, as clinical practice evolves over time, patient populations participating in biomarker (or therapeutic) studies also change. In this instance, both the clinical pCR predictor nomogram and the DLDA30 genomic assay were developed for a general breast cancer population including HER2-positve cases. However, contemporary validation of these predictors is limited to HER2-normal cases due to the widespread use of trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. This shift in patient population likely contributes to the decreased performance of these two predictors.

A theoretical advantage of cell line-derived genomic predictors is that they may be less sensitive to shifts in patient population since, in their original form, these are not trained on a historical patient cohort but rather on clean and easily manipulated in vitro cell line models. However, the purely cell line derived drug-specific predictors did not perform well, only the paclitaxel predictor showed modest but significant discriminating power in the human cases. In order to optimally train a predictor that relies on informative genes from cell lines, it was necessary to use information from a separate human data set with known response outcome.

These results raise an important question; why did some of the cell line derived-predictors worked for some drugs but not for others in human cases? For some drugs it may be easier to find response markers in the RNA space than for others. The mechanisms of drug resistance are substantially more complex in vivo than in vitro. Important patient-to-patient differences in drug metabolism and tumor microenvironment (immune response, interstitial pressure and vascular leakiness) cannot be captured by cell line gene expression data. Considering these complexities, it is remarkable that a cell line-derived paclitaxel (and to lesser degree a doxorubicin) response predictor retained predictive value in patients at all. In order to move this field forward it will be important to systematically examine which cell line-derived response markers retain predictive value in human tumors and why.

Some limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. Our grouping of the validation cases into pCR and RD are clinically justified because cases with pCR have excellent long-term survival most probably due to their chemotherapy sensitivity, whereas those with RD have a variable outcome. However, most cases with RD have some degree of tumor response and therefore these cases are not strictly resistant to therapy even if their long-term benefit from chemotherapy remains uncertain. To address the impact of this dichotomization we also correlated prediction scores with residual cancer burden treated as a continuous response variable and results have not changed. Also, the cell line derived predictors were developed for single agents and their combination, assuming independence between drug sensitivities, was used to define a multi-drug sensitivity score. Our combination score approach may be too naïve to capture the complexity of potential multi-drug interactions that can occur during treatment. Unfortunately, genomic data from patients treated with single drugs was not available for validation. The lack of data from patients with different single agent therapies also limits the ability to truly evaluate the regimen specificity of the cell-line derived signatures. From the current results it is impossible to infer if the paclitaxel signature represent a general chemotherapy sensitivity marker or it is truly predicts for paclitaxel sensitivity. This is an important question that will need to be studied in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Overall analysis schema

Supplementary Figure 2. Calibration curves for the 4 distinct predictors. The curves plot the agreement between observed and predicted probabilities of pCR. The four points on each curve correspond to the quantiles of the empirical distribution of the predictive probability.

Supplementary Table 1. Genes and probe sets used in the DLDA30 and paclitaxel, 5-FU, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide COXEN models.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Daniel F. Hayes for valuable comments and suggestions during the planning phase of this project. Charles Coutant thanks « l'Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer », « le Ministère Français des Affaires Etrangères et Européennes » as part of Lavoisier program, « le Collège National des Gynécologues et Obstétriciens Français » and « la Fondation de France » as part of its collaboration with « la Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer ».

Funding source: This research was supported grants from the NIH R01HL081690 (JKL), R01CA075115 (DT), The Breast Cancer Research Foundation (LP and WFS), The MD Anderson Cancer Center Faculty Incentive Funds (WFS) and the Commonwealth Cancer Fundation (LP, WFS), “L'Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer” (CC), “Le Ministère Français des Affaires Etrangères et Européennes” as part of Lavoisier program (CC), “Le Collège National des Gynécologues et Obstétriciens Français” (CC) and “La Fondation de France” as part of its collaboration with “la Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer” (CC).

Footnotes

code is available at http://bioinformatics.mdanderson.org/pubdata.html

Contributors

All authors took part in the design and implementation of the study, and read and approved the final report. The corresponding author has had access to all data in this study

The first author, Jae K. Lee from the Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Virginia Health Sciences Center, Charlottesville, designed this work, collected and analyzed all the data and wrote the article.

Charles Coutant from the Department of Breast Medical Oncology, UT MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston and the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hôpital Tenon, Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris, University Pierre et Marie curie – Paris, UPRES EA 4053, Paris analyzed all the data.

Young-Chul Kim from the Division of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Virginia Health Sciences Center, Charlottesville analyzed all the data.

Yuan Qi from the Department of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, UT MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston analyzed all the data.

Dan Theodorescu from the Department of Urology, University of Virginia Health Sciences Center, Charlottesville, collected the local data from patients.

W Fraser Symmans from the Department of Pathology, UT MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston provided specimens and collected the local data

Keith Baggerly from the Department of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, UT MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston designed this work and analyzed the data.

Roman Rouzier from the Department of Obstetric and Gynecology, Hôpital Tenon, Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris, Paris, France wrote supervised and analyzed the data.

The corresponding author and senior author, Lajos Pusztai from the Department of Breast Medical Oncology, UT MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston supervised this work, analyzed all the data and wrote the article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Translational Relevance

Chemotherapy response predictors can be constructed from clinical variables or from gene expression data of human cancers with known response to chemotherapy, or using data from cell lines with known drug sensitivity. We compared these 3 methods testing 4 different a priori defined predictors in 100 cancers treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The clinical variable-based and empirically-derived genomic predictors worked equally well but the pure, cell line-trained genomic predictor showed poor performance. Many genes that were informative of drug response in cell lines were not informative in human cancers and even genes that retained informative value needed to be trained on human data, rather than cell lines, to achieve good predictive performance. The empirically-derived genomic response predictor developed from all breast cancers relied heavily on identifying known clinical phenotypes that limits its practical value; the next generation of such markers will need to be developed separately for distinct breast cancer subtypes.

References

- 1.Lee JK, Havaleshko DM, Cho H, et al. A strategy for predicting the chemosensitivity of human cancers and its application to drug discovery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13086–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610292104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potti A, Dressman HK, Bild A, et al. Genomic signatures to guide the use of chemotherapeutics. Nat Med. 2006;12:1294–300. doi: 10.1038/nm1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonnefoi H, Potti A, Delorenzi M, et al. Validation of gene signatures that predict the response of breast cancer to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a substudy of the EORTC 10994/BIG 00-01 clinical trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:1071–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70345-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coombes KR, Wang J, Baggerly KA. Microarrays: retracing steps. Nat Med. 2007;13:1276–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1107-1276b. author reply 7-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu DS, Balakumaran BS, Acharya CR, et al. Pharmacogenomic strategies provide a rational approach to the treatment of cisplatin-resistant patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4350–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang JC, Wooten EC, Tsimelzon A, et al. Gene expression profiling for the prediction of therapeutic response to docetaxel in patients with breast cancer. Lancet. 2003;362:362–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hess KR, Anderson K, Symmans WF, et al. Pharmacogenomic predictor of sensitivity to preoperative chemotherapy with paclitaxel and fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4236–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.6861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rouzier R, Pusztai L, Delaloge S, et al. Nomograms to predict pathologic complete response and metastasis-free survival after preoperative chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8331–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Symmans WF, Ayers M, Clark EA, et al. Total RNA yield and microarray gene expression profiles from fine-needle aspiration biopsy and core-needle biopsy samples of breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:2960–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liedtke C, Mazouni C, Hess KR, et al. Response to neoadjuvant therapy and long-term survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1275–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Symmans WF, Peintinger F, Hatzis C, et al. Measurement of residual breast cancer burden to predict survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4414–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller LD, Smeds J, George J, et al. An expression signature for p53 status in human breast cancer predicts mutation status, transcriptional effects, and patient survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13550–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506230102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dressman HK, Berchuck A, Chan G, et al. An integrated genomic-based approach to individualized treatment of patients with advanced-stage ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:517–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takata R, Katagiri T, Kanehira M, et al. Validation study of the prediction system for clinical response of M-VAC neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:113–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3:32–5. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::aid-cncr2820030106>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coutant C, Olivier C, Lambaudie E, et al. Comparison of models to predict nonsentinel lymph node status in breast cancer patients with metastatic sentinel lymph nodes: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2800–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.7418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green MC, Buzdar AU, Smith T, et al. Weekly paclitaxel improves pathologic complete remission in operable breast cancer when compared with paclitaxel once every 3 weeks. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5983–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andre F, Mazouni C, Liedtke C, et al. HER2 expression and efficacy of preoperative paclitaxel/FAC chemotherapy in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;108:183–90. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9594-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buzdar AU, Valero V, Ibrahim NK, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy with paclitaxel followed by 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy and concurrent trastuzumab in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive operable breast cancer: an update of the initial randomized study population and data of additional patients treated with the same regimen. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:228–33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ein-Dor L, Kela I, Getz G, Givol D, Domany E. Outcome signature genes in breast cancer: is there a unique set? Bioinformatics. 2005;21:171–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michiels S, Koscielny S, Hill C. Prediction of cancer outcome with microarrays: a multiple random validation strategy. Lancet. 2005;365:488–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17866-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ransohoff DF. Bias as a threat to the validity of cancer molecular-marker research. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:142–9. doi: 10.1038/nrc1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Overall analysis schema

Supplementary Figure 2. Calibration curves for the 4 distinct predictors. The curves plot the agreement between observed and predicted probabilities of pCR. The four points on each curve correspond to the quantiles of the empirical distribution of the predictive probability.

Supplementary Table 1. Genes and probe sets used in the DLDA30 and paclitaxel, 5-FU, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide COXEN models.