Abstract

The aging of the population and, concomitantly, of the workforce has a number of important implications for governments, businesses, and workers. In this article, we examine the prospects for the employability of older workers as home-based teleworkers. This alternative work could accommodate many of the needs and preferences of older workers and at the same time benefit organizations. However, before telework can be considered a viable work option for many older workers there are a number of issues to consider, including the ability of older workers to adapt to the technological demands that are typically associated with telework jobs and managerial attitudes about older workers and about telework. Through an integrated examination of these and other issues, our goal is to provide a comprehensive understanding of the challenges associated with employing older workers as teleworkers. We also present findings from a questionnaire study that assessed managers’ perceptions of worker attributes desirable for telework and how older workers compare to younger workers on these attributes. The sample included 314 managers with varying degrees of managerial experience from a large variety of companies in the United States. The results presented a mixed picture with respect to the employability of older workers as teleworkers, and strongly suggested that less experienced managers would be more resistant to hiring older people as teleworkers. We conclude with a number of recommendations for improving the prospects for employment of older workers for this type of work arrangement.

1. INTRODUCTION

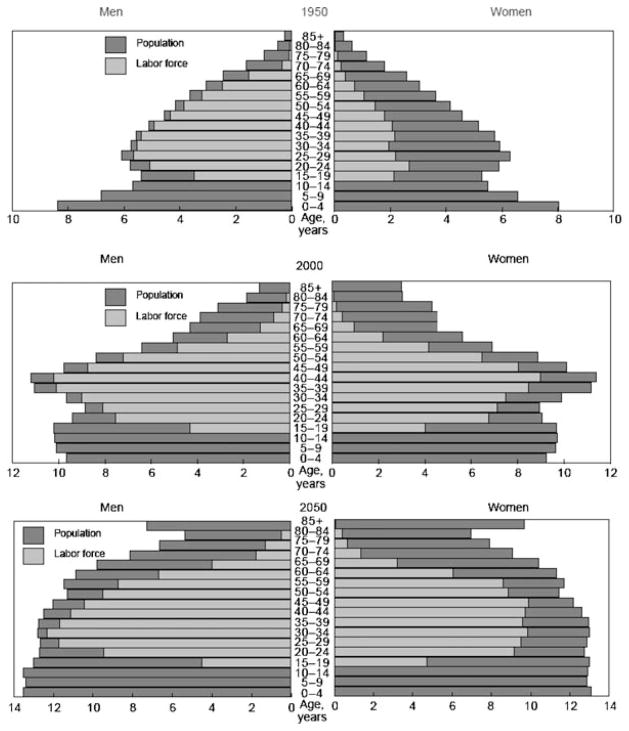

In the United States, the age distribution of the population has transformed from one characterized by an age pyramid through the 19th and most of the 20th century, to an age column that reflects an age distribution that is much more evenly distributed across all ages (Himes, 2001). As shown in Figure 1, a similar pattern is occurring in the labor force in the United States with a projected increase in the number of older workers (Toossi, 2006). These population and workforce demographic trends in the United States are also occurring in other parts of the world, particularly in Canada, Japan, Australia, and many of the European Union (EU) member states. An inability for the work sector to accommodate this larger number of older people could translate into increased financial pressure on a shrinking share of younger workers to fund the retirement and health care of a growing older nonworking population (Friedberg, 2000; Johnson & Steuerle, 2004; Warr, 2000). It could also translate into labor and skill shortages for many industries and organizations. In fact, the European Commission has forecasted that the EU will face a shortage of approximately 20.8 million people of working age by 2030 (Villosio, Di Pierro, Giordanengo, Pasqua, & Richiardi, 2008).

Figure 1.

U.S. population and labor force (in millions), 1950, 2000, and projected 2050. Source: Toossi, 2006.

To offset these concerns, greater efforts are needed by employers to recruit and retain older workers reaching retirement ages. However, in the United States, few employers have actively begun to do so (Eyster, Johnson, & Toder, 2008). To date, industries in the United States that have most actively recruited older workers are health care and energy, which already face imminent labor shortages. This is unfortunate as many older workers are highly knowledgeable and skilled and embody desirable work-related attributes such as maturity and dependability. Also, working environments have become significantly less physically demanding, which has resulted in decreased health and safety risks for older workers (Eyster, Johnson, & Toder; 2008; Villosio et al., 2008).

Governments and employers are not the only potential beneficiaries of an investment in policies directed at recruiting and retaining older workers—older people themselves stand to gain. According to the Employment Benefit Research Institute (WFC Resources, 2006), many U.S. workers can no longer count on traditional “defined benefit” pension plans and are not putting away sufficient funds in alternative retirement or other types of savings plans. Delaying retirement may also promote physical and emotional health by keeping older individuals active and engaged (Calvo, 2006), which can have an enormous impact as well on the economic sustainability of governments and businesses.

In recognition of the need to recruit and retain older workers, governments and businesses have begun to consider or rethink a number of strategies and policies targeting this worker population. For example, in Europe efforts have been directed at better understanding the quality of working life to explain the decisions by older workers to leave the work sector (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2002). Four aspects of job and employment quality that were recently explored with respect to age in the most recent European Working Conditions Survey that included the 27 EU member states (Villosio et al., 2008), were: career and employment security (exposure to job insecurity and discrimination); health and well-being (risk exposure, involvement in high-performance work organizations); skills development (opportunities to learn new things at work); and reconciliation of working and nonworking life (need for more flexible work arrangements). Correspondingly, the U.S. Department of Labor’s Employment & Training Administration commissioned a report from the Taskforce on the Aging of the American Workforce, which described current strategies used by employers as well as nonprofit organizations, educational institutions, and the government to recruit and retain older workers, or otherwise facilitate their employment (Eyster, Johnson, & Toder, 2008). For employers, the primary emphasis was on the benefits of offering flexible work arrangements and phased retirement options.

Consistent with this theme, the focus of this article is on the consideration of telework, particularly home-based telework, as a flexible work arrangement that can potentially accommodate the needs of many older workers. Patrickson (2002) is one of the few that has even entertained the idea of promoting telework for older workers, and almost no empirical data exist on this topic. The opportunity to telework, especially from the home, can offer an added incentive for many older workers to delay retirement or reenter the workforce; at the same time, employers could tap into this expanded labor pool without having to consider costs such as those associated with office space and transportation. However, there are a number of considerations that need to be addressed to maximize this opportunity for older people, including the technological demands of telework jobs, the technology skills of older workers, and managers’ attitudes toward telework and older workers.

Following a brief discussion of telework and why this type of work arrangement may be uniquely appealing to many older workers, we consider a number of important issues that need to be resolved to improve the prospects of employing older workers as teleworkers. In particular, our focus is on issues that concern the capability for older workers to perform technologically based telework tasks (Czaja et al., 2006; Sharit et al., 2004) and on managerial views of older workers, especially as they might concern worker-related attributes such as trustworthiness, reliability, technology skills, and adaptability (Handy, 1995; Kite, Stokdale, & Whitley, 2005; Warr & Pennington, 1993) that may be important for telework. We then present data from a recently completed study that evaluated managers’ attitudes regarding telework and their perceptions concerning how younger and older workers compare on a number of worker attributes of potential importance for telework. We conclude with some recommendations that provide a broader perspective of the issue of improving the viability of telework as an alternative work arrangement for older workers.

2. TELEWORK

Telework, which is still sometimes referred to as telecommuting in the United States (Ellison, 2004), can be broadly conceptualized as an “anytime-anyplace” form of work (Buessing, 2000). In principle, this definition includes working at teleworking centers (or “satellite sites”) closer to home than the usual workplace, mobile work such as sales, and home-based work by people who are self-employed. Our focus, however, is on employees of organizations who are given the opportunity to perform their jobs from their homes. Obviously, not all jobs are suitable for telework—tasks that require face-to-face communication or interfacing to equipment or systems located at the organization’s primary work site clearly would not be amenable to telework. However, with increased advances in computer-based technologies, many more work tasks, such as those involving data processing, accounting, computer programming, design, customer service, quality control, and health care, can be performed from the home.

Largely because of developments in information and communication technologies (ICTs) and reductions in their cost, as well as the recognition of a wide array of benefits associated with telework, growth in telework has surged in the United States, Europe, and Australia. The number of Americans allowed by their employers to work at least one day a month from their homes increased from 9.9 million to 12.4 million between 2005 and 2006; if contract workers are included, about one fifth of the total workforce—28.7 million workers—worked from home at least one day a month in 2006 (Eyster, Johnson, & Toder, 2008). Many companies, especially those in the financial, information technology, and communications sectors, are now offering telework opportunities (Dychtwald, Erickson, & Morison, 2006). Some organizations that provide business process outsourcing for companies rely on a “work-at-home model” that has sometimes been referred to as a virtual or remote workforce.

However, the reality is that the majority of workplaces do not offer telework opportunities to employees, and when they are offered they are limited in scope with respect to the amount of time an employee can work from the home (Potter, 2003). This is true even in the federal sector, despite the fact that the General Services Administration (GSA) has assigned telework coordinators to each of its agencies (www.gsa.gov), and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) has provided numerous guidelines for managers of these various agencies regarding the management of telework programs (OPM, 2003). Although the opportunity to telework, according to the latest government guidelines, is supposed to occur at least one day a week (for positions that are deemed by each agency as appropriate for telework and for workers whose performance is deemed satisfactory), there are indications that these guidelines have been abused by providing telework on a project-oriented or irregular (as opposed to a recurring) basis. The concern for retaining older workers through a telework arrangement was recently voiced by the head of the U.S. government’s telework program: “With fierce competition for human capital and a retirement wave, telework provides a work style to retain older workers and recruit younger workers looking for flexibility” (Federal Computer Week [FCW.com], 2008).

According to Potter (2003), the principal reason why telework is not extensively used in most organizations is due to the premium that first-line supervisors and middle managers place on the “socialization aspects of the workplace” as a basis for confirming whether the worker is meeting performance standards and adapting to corporate culture. Other contributing factors include difficulty in ascertaining the economic benefits of such programs and a lack of training regarding how to best manage telework. Thus, for a vast number of organizations the decision to allow an individual to telework from the home will come down to the attitudes that their managers harbor about telework—in particular, their feelings about managing workers without the benefit of face-to-face interaction. This lack of visibility makes trust in a worker a critical factor in the willingness for a manager to provide an employee with the opportunity to telework (Handy, 1995). What is less certain is how this factor might influence the prospects for older workers to gain employment as home-based teleworkers.

2.1. Benefits and Concerns Associated with Telework

In recent years, both the benefits and the concerns associated with telework have become more clearly articulated from the perspectives of both the employer and the employee (e.g., Buessing, 2000; Illegems & Verbeke, 2004; Kurland & Bailey, 1999; Potter, 2003). For employers, some of these benefits include an increased labor pool (to include older people and people with disabilities) and enhanced recruiting potential; improved retention of qualified staff; less sick leave and absenteeism; reduced costs for office space and parking; heightened productivity (due to fewer interruptions and better concentration); improved (due to extended) customer service; and improved organizational image (e.g., in promoting a better environment). Concerns for organizations include negative effects on organizational culture, reduced loyalty, reduced tacit knowledge transfer, and negative impacts on activities requiring teamwork, all by virtue of the loss of socialization aspects of the workplace and reduced professional interaction; increased difficulty in monitoring and assessing employee performance; needed investments in ICTs; less control over data security; and less control and greater ambiguity with respect to legal issues governing work at home, such as worker injuries or health risks.

From the perspective of the employee, the benefits of telework include a reduction or elimination of the (often stressful) work commute; fewer distractions and improved concentration; increased satisfaction (due to increased autonomy and control over how the work is done); the ability to accommodate disabilities or mobility problems; better opportunities for part-time work; and an enhanced ability to balance work life with family or personal responsibilities and needs. The concerns for teleworkers include isolation and separation (the effects of which are highly variable among individuals); distractions that can arise within the home; and the perceived pressure on the part of the teleworker to be “visible” (which may result in resorting to overwork, e.g., in the form of frequent checking of e-mail). Each of these concerns can have important implications for teleworkers.

The physical isolation generally associated with telework not only can compromise potentially important social interactions, but it can also insulate teleworkers from coworkers and managers. This, in turn, could lead to a loss of critical organizational knowledge that is often derived through informal or spontaneous interchanges with coworkers, support staff, and management—the basis for what is sometimes referred to as “incidental learning” (Brown & Duguid, 2000). With respect to the latter concern, in the absence of “visibility” management could assume that the worker has “disappeared,” which could undermine the trust that management requires for allowing their workers to telework (Ellison, 2004). The isolation of managers from their teleworkers also shifts the burden on managers from supervising employees to supervising work (Ellison, 2004; Reynolds & Brusseau, 1998). In many organizations, this shift in emphasis may entail additional procedures for demonstrating the satisfaction of work objectives (e.g., through e-mail or video conferencing), which could exact considerable additional pressure on supervisors and also influence their decisions regarding the types of workers who would be allowed to telework.

2.2. Telework as an Employment Opportunity for Older Workers

Within the context of an increased expansion of home-based work in Australia, Patrickson (2002) explored the unique potential of teleworking as an employment opportunity for older workers. Her emphasis was on the benefits to older workers (as well as other marginalized workers) of being rendered “invisible” by the reduced socialization implicit to telework. The assumption was that if the focus is on worker output, as opposed to other visible attributes such as age, older workers could be offered expanded employment opportunities. Patrickson also acknowledged the attractiveness of part-time work to many older workers, which telework can potentially easily accommodate; this is also in line with current evidence indicating a preference by older workers for nontraditional working arrangements (Eyster, Johnson, & Toder, 2008). Although Patrickson’s primary emphasis was on data processing, she concluded that, with proper training, older workers could acquire the skills needed to perform less routine and more complex problem-solving telework tasks.

In general, we concur with Patrickson’s (2002) views concerning the unique opportunities that telework may provide for older workers. In fact, there are a number of additional benefits of telework that are particularly relevant to older individuals and that merit attention. For example, an increasingly older population is resulting in an increased caregiving burden for many older people (Fredriksen & Scharlach, 1997; Schulz & Martire, in press; Villosio et al., 2008), which may require many of them to spend considerably more time working from their homes. Older workers are also likely to be more susceptible to the potential burdens associated with commuting to work, which telework can eliminate, and are likely to desire a greater balance between personal and work lives. In addition, older workers may place greater value on the enhanced security that comes with working from their homes, especially if they have health or other personal issues that can be better managed in these environments.

The prospects for employing older people as teleworkers, however, involves a complex dynamic that requires a consideration and elaboration of issues beyond those pursued in the study by Patrickson (2002). A key aspect of this dynamic is that many telework jobs are dependent—indeed, are inextricably linked—to ICTs that extend beyond simple data-processing operations. These technologies may include handheld wireless devices or desktop video conferencing equipment, or may require sophisticated Internet information-seeking skills. Thus, it is essential that the older worker has the skills and the confidence to interact with technology. Unfortunately, data indicate that, as compared to younger adults, older people in the United States report lower use of technology (Czaja et al., 2006) and are far less likely to be users of computer technology and the Internet (Pew Internet & American Life Project, 2006). The reduced use of technology seen in older adults may be attributed in part to age-related declines in cognitive abilities (Park & Schwartz, 2000) such as working memory, selective attention, spatial cognition, and reasoning and to findings suggesting that they are less comfortable and less confident with technology adoption (e.g., Czaja et al., 2006). Many of these problems can largely be alleviated through appropriate user-interface design and training strategies that accommodate the capabilities and limitations of older adults (Fisk, Rogers, Charness, Czaja, & Sharit, 2009). However, the successful implementation of these strategies depends to a large extent on the willingness of employers to provide older workers with opportunities to participate in training programs and to understand and accommodate the needs and preferences of older workers. Unfortunately, there is only limited evidence that employers are willing to take on this responsibility (Coleman, 1998).

There are also a number of ergonomic workspace issues that employers will need to consider to accommodate older individuals working from the home. For example, there are changes in motor skills that occur with aging, including slower response times, disruptions in coordination, greater difficulty in maintaining continuous movements, and reduced flexibility in movement (Kroemer, 2007). Chronic conditions such as arthritis are also more prevalent in older individuals. Thus, issues of equipment and workplace design and guidelines for work/rest schedules have particular relevance for older workers. Consequently, ambiguity in occupational safety and health legislation regarding employer liability for injury or adverse health consequences to teleworkers (Potter, 2003) is likely, if anything, to discourage offering telework opportunities to older workers. Therefore, it is imperative that employers use strategies to effectively communicate proper workspace arrangements and work practices for older teleworkers.

3. MANAGERIAL VIEWS OF OLDER WORKERS

Another important consideration is the attitudes that managers may have regarding employing older workers as teleworkers. There are relatively extensive data in the literature indicating that older workers are not perceived as favorably as younger workers (e.g., Finkelstein, Burke, & Raju, 1995; Gordon & Arvey, 2004; Kite, Stokdale, & Whitley, 2005; Perry, Kulik, & Bourhis, 1996). Recent data from a study examining age discrimination in the workplace (Lahey, 2005), which indicated that younger adults were more than 40% more likely than older adults to be called back for a job interview, are especially disturbing as they suggested that the demand for older workers is less than that for younger workers with the same backgrounds and work experiences.

These data are consistent with perceptions held by many managers that older workers are less flexible and less adaptive than are younger workers and less willing and able to work. Many of these perceptions, however, are based on a lack of knowledge about aging and, particularly, about aging and work. These attitudes are especially likely to be manifest in today’s jobs where there has been a rapid infusion of technology into many work activities and an emphasis on processing large amounts of information at a rapid pace. Common myths that older people are less able or less willing to learn to perform technological tasks are not supported by the literature (Charness, Czaja, & Sharit, 2007). In fact, in a study involving performance of a simulated e-mail based telework customer service job, the findings indicated that the older (66 to 80 years) participants were capable of learning the task, and with practice over a four-day period, able to closely match the performance of the people 50 to 65 years of age (Sharit et al., 2004). However, the findings also suggested that older adults may require increased emphasis during training on use of any task-related technologies, and that increased consideration may need to be given to workspace design factors.

Not all data indicate a discriminatory attitude by employers toward older workers. For example, a survey by Buck Consultants (2007) found that managers believed that older workers offered a number of important advantages such as corporate knowledge, reliability, and dedication. At the same time, however, there was evidence that employers did not view older workers as being creative or open to learning new things. Warr and Pennington (1993) found that personnel managers in the U.K. believed, among other positive beliefs, that workers older than 40 years had more experience; were more loyal, reliable, confident, and conscientious; and worked better in teams. However, older workers also were considered to be less able to accept new technology or grasp new ideas, less adaptable to change, and less interested in training (Warr & Pennington, 1993).

3.1. What are the Worker Attributes Important for Telework?

As telework has a number of unique aspects, a critical question is: What are the worker-related attributes that might be critical in a manager’s decision to provide the opportunity for a worker to telework? If we can better understand the relative importance that managers subscribe to such attributes and how they feel older workers compare with younger workers on these attributes, we may be in a much better position to gauge the prospects for older workers gaining employment as teleworkers. Knowledge of this type also is important to the development of strategies, such as manager training programs, to help minimize existing misunderstandings and myths about older workers.

To gather initial data on this issue we administered a questionnaire regarding telework, worker attributes important to telework, and older workers to managers from a wide variety of organizations. Our overall goal was to gain insight into the employment prospects for older workers as teleworkers. The development of the questionnaire was based on a review of the existing literature and existing guidelines for telework. We identified 13 worker attributes that were likely to be important to the selection of workers for telework including: trust, reliability, maturity, independence, time-management ability, adaptability, tenure (time on the job), experience in the work activity, written and verbal communication skills, ability to work on teams, technology skills, and health status. Trust, reliability, and maturity are likely to be interrelated and represent the core attributes that are expected to be essential to a manager’s perception of trust in an individual and in the individual’s ability to work productively at home with virtual supervision. Time-management ability and work experience are also deemed important as being able to manage one’s own time and having sufficient experience with work tasks are factors that are likely to increase the confidence that managers would have in a worker’s ability to meet deadlines and performance quotas. Adaptability is also an important attribute given the possibility that telework may introduce many new ways of performing work tasks. Tenure (time on the job) could also prove critical, as it may influence perceptions regarding a worker’s commitment to a company or organization as well as the worker’s job-related skills.

Although traditional work skills, such as the ability to work on teams and writing and verbal abilities, may not, on first thought, be considered particularly relevant to some telework jobs, these skills are likely to play an important role in many current and future telework jobs given the increased emphasis on collaborative work and technology-based communication formats (e.g., e-mail and video conferencing). Perceptions regarding a worker’s technology skills will become increasingly important to telework as much of this work involves some form of computer or communication technology. Finally, health status is important as it may influence the degree to which a manager perceives if someone, who may not wish or be able to commute to a traditional workplace, is in fact able to work at home.

4. METHOD

The questionnaire was directed at people in managerial positions and was implemented on the Internet. It was composed of a number of sections, including an initial section on the status of telework in the manager’s company, a section that collected data concerning attitudes that managers had about telework, and a section that collected data related to the nature of the manager’s company or organization (e.g., size and type of industry) and his or her position (e.g., years of experience as a manager overall and in the current position). The entire instrument took approximately 12 to 15 minutes to complete, and its content and mechanisms of delivery were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

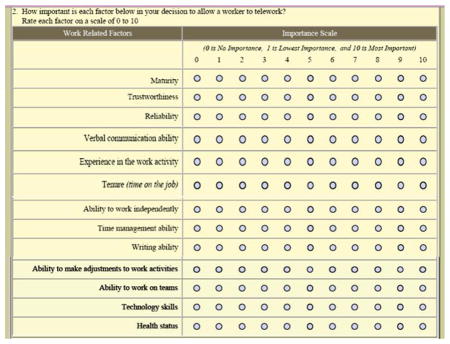

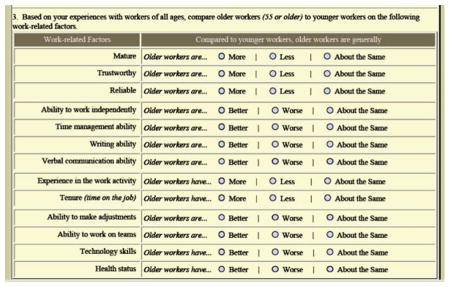

The primary focus of this article is on the section of the questionnaire that addressed managers’ perceptions about the potential employability of older workers as teleworkers (Appendix 1). Respondents were asked to rate, from 0 to 10, each of 13 worker-related attributes noted earlier in terms of its importance (where 0 indicated no importance and 10 indicated most important) in deciding whether to allow a worker to telework. Immediately following these ratings, the respondents were asked to compare older and younger workers on these work-related attributes. This strategy was undertaken to avoid explicitly asking managers about their feelings concerning employing older teleworkers, which could have had discriminatory implications.

We also present data on the managers’ overall perceptions regarding telework. The section of the questionnaire related to attitudes that managers had about telework contained 22 questions, which were scored on a 5-point scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree). To determine which questions were associated with the most and least positive responses, each question was scored between 1 and 5, with scoring reversed so that 5 always represented the most positive response to the question.

Respondents were recruited using three strategies: personal calls made to managers based on listings of information regarding a variety of companies located throughout the United States; an “e-mail blast” from an Internet marketing company; and an “e-mail blast” from the authors’ university to alumni who were employed in managerial positions across the United States. In responding to the questions, the managers were to assume that the telework site in question was the employee’s home or residence.

5. RESULTS

Three hundred and fourteen participants completed and submitted the questionnaire. One hundred thirty-three (42.4%) of the respondents reported being associated with a small company (<500 employees), 62 (19.7%) reported their company to be medium-sized (between 500 and 5000 employees), and 118 (37.6%) reported their company to be large (>5000 employees). Overall, the data indicated that this sample of managers represented a large variety of mostly private sector industries. Table 1 lists the types of industries to which at least five respondents indicated an affiliation; many other industry affiliations were indicated by fewer numbers of respondents. The sample was also diverse and relatively balanced in terms of years of overall managerial experience. Seventy-two of the respondents (22.9%) indicated that they had 5 or fewer years of managerial experience, 80 (25.5%) indicated that they had more than 5 but less than 10 years of experience, 83 (26.4%) indicated that they had between 10 and 20 years of experience, and 78 (24.8%) indicated that they had more than 20 years of experience as a manager.

TABLE 1.

Industries for Which There Was an Association with at Least Five Respondents

| Industry | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Computer technologies | 59 (18.8%) |

| Computer services | 52 (16.6%) |

| Educational services | 37 (11.8%) |

| Telecommunication technologies | 26 (8.3%) |

| Brokerages/Financial services | 21 (6.7%) |

| Hospitals | 20 (6.4%) |

| Publishing | 20 (6.4%) |

| Hospitality | 17 (5.4%) |

| Insurance | 17 (5.4%) |

| Medical products | 17 (5.4%) |

| Banking | 15 (4.8%) |

| Educational products | 15 (4.8%) |

| Logistical services | 14 (4.5%) |

| Transportation services | 14 (4.5%) |

| Retail stores | 14 (4.5%) |

| Inventory/auditing | 13 (4.1%) |

| Construction | 12 (3.8%) |

| Military services | 12 (3.8%) |

| Entertainment | 10 (3.2%) |

| Law firm/legal services | 10 (3.2%) |

| Electronics manufacturing | 8 (2.5%) |

| Aviation manufacturing | 7 (2.2%) |

| Pharmaceutical production | 7 (2.2%) |

| News/Broadcast media | 6 (1.9%) |

| Food products | 5 (1.6%) |

Table 2 presents data on the three questions that resulted in the most positive ratings and the three questions that resulted in the least positive ratings in response to 22 questionnaire items that addressed attitudes about telework. As the data indicate, although the respondents strongly believed that telework can improve the retention and satisfaction of workers who would otherwise have long commutes, there was also a strong concern that allowing opportunities for some workers to telework could cause friction among workers who cannot telework.

TABLE 2.

Questionnaire Items Concerning Feelings about Telework That Were Given the Most and Least Positive Ratings by Managers

| N | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Items for which respondents provided the most positive ratings | |||

| Telework benefits workers with long commutes and thus improves their retention and satisfaction. | 310 | 4.32 | 0.67 |

| Telework provides greater flexibility in scheduling and thus increases satisfaction. | 314 | 4.22 | 0.72 |

| Telework accommodates handicapped workers. | 311 | 4.08 | 0.63 |

| Items for which respondents provided the least positive ratings | |||

| Allowing opportunities for some workers to telework would cause friction among workers who cannot telework. | 313 | 2.73 | 0.98 |

| Teleworkers could get distracted by family or other pressures at home and thus experience stress in meeting work performance objectives. | 314 | 2.81 | 0.96 |

| There are home safety or other legal issues associated with telework involving employer responsibility. | 312 | 2.82 | 0.94 |

Note. N : number; M: mean; SD: standard deviation.

Table 3 presents the means and standard deviations of the respondents’ ratings (from 0 to 10) of the 13 worker-related variables with respect to the importance attributed to each of these variables in the decision to allow a worker to telework (Appendix 1). The correlations among these 13 variables are provided in Table 4. As indicated in Table 3, the respondents considered trustworthiness, reliability, ability to work independently, and time-management ability to be the most important attributes. These variables were also significantly inter-correlated, as indicated in Table 4. Other relationships among the variables are also implied in this table.

TABLE 3.

Mean Ratings of the Importance of Each of 13 Worker-Related Attributes in Impacting a Manager’s Decision to Allow a Worker to Telework (N = 314)

| Worker-Related Attributes | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Trustworthiness | 9.31 | 1.11 |

| Reliability | 9.31 | 1.06 |

| Ability to work independently | 9.31 | 1.08 |

| Time-management ability | 9.04 | 1.36 |

| Maturity | 8.67 | 1.62 |

| Experience in the work activity | 8.29 | 1.71 |

| Technology skills | 8.25 | 1.70 |

| Ability to make adjustments to work activities | 8.11 | 1.62 |

| Verbal communication ability | 7.25 | 2.26 |

| Writing ability | 6.67 | 2.40 |

| Ability to work on teams | 6.62 | 2.57 |

| Tenure (time on the job) | 5.66 | 2.86 |

| Health status | 4.66 | 2.99 |

Note. M: mean; SD: standard deviation.

TABLE 4.

Correlations among the 13 Worker-Related Attributes (Kendalls tau-b)

| (Tr) | (R) | (WI) | (TM) | (M) | (E) | (TS) | (A) | (V) | (Wr) | (TW) | (Te) | (HS) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust (Tr) | |||||||||||||

| Reliability (R) | .608** | ||||||||||||

| Ability to work independently (WI) | .383** | .458** | |||||||||||

| Time management (TM) | .336** | .405** | .458** | ||||||||||

| Maturity (M) | .494** | .463** | .370** | .293** | |||||||||

| Experience in the work activity (E) | .224** | .181** | .233** | .255** | .232** | ||||||||

| Technology skills (TS) | .217** | .213** | .278** | .292** | .190** | .291** | |||||||

| Adjustments (A) | .228** | .275** | .371** | .343** | .237** | .426** | .316** | ||||||

| Verbal communication (V) | .152** | .198** | .217** | .275** | .211** | .323** | .243** | .368** | |||||

| Writing (Wr) | .139** | .181** | .268** | .265** | .212** | .213** | .313** | .319** | .479** | ||||

| Ability to work on teams (TW) | .054 | .083 | .110* | .193** | .099* | .303** | .306** | .322** | .356** | .322** | |||

| Tenure (Te) | .097* | .113* | .084 | .138** | .112* | .297** | .110* | .230** | .159** | .188** | .179** | ||

| Health status (HS) | .093* | .110* | .095* | .072 | .111* | .137** | .149** | .086* | .122** | .156** | .189** | .253** | |

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Table 5 summarizes the comparisons between older and younger workers in terms of the percentage of the respondents who indicated either “less/worse than,” “about the same,” or “more/better than” (Appendix 1) on each of these work-related attributes. Not surprisingly, the majority of the responses for a number of these attributes were “about the same.” Importantly, as implied by the confidence intervals associated with the response percentages, older workers were significantly favored over younger workers for the four attributes that the respondents considered most important for allowing a worker to telework: trustworthiness, reliability, ability to work independently, and time-management ability. Similarly, older workers were significantly favored over younger workers with regard to maturity, experience in the work activity, and verbal communication and writing abilities. Conversely, with respect to the ability to make adjustments and work on teams, younger workers were viewed significantly more favorably than older workers, and were overwhelmingly favored over older workers with regard to technology skills.

TABLE 5.

Numbers and Percentages of Responses Favoring Older Workers, Favoring Younger Workers, or That Were Neutral with Regard to Each of the 13 Worker-Related Attributes

| Worker-Related Attribute | N | Older Workers Are: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less/Worse |

About the Same |

More/Better |

|||||

| n | Percentage [95% CI] | n | Percentage [95% CI] | n | Percentage [95% CI] | ||

| Trustworthiness | 305 | 1 | 0.3 [0.0–1.5] |

199 | 65.2 [59.8–70.4] |

105 | 34.4 [29.3–39.9] |

| Reliability | 303 | 11 | 3.6 [1.9–6.2] |

155 | 51.2 [45.5–56.8] |

137 | 45.2 [39.7–50.8] |

| Ability to work independently | 306 | 22 | 7.2 [4.7–10.5] |

171 | 55.9 [50.3–61.4] |

113 | 36.9 [31.7–42.4] |

| Time-management ability | 305 | 25 | 8.2 [5.5–11.7] |

172 | 56.4 [50.8–61.9] |

108 | 35.4 [30.2–40.9] |

| Maturity | 306 | 4 | 1.3 [0.4–3.1] |

60 | 19.6 [15.5–24.3] |

242 | 79.1 [74.3–83.4] |

| Experience in the work activity | 305 | 2 | 0.7 [0.1–2.1] |

65 | 21.3 [17.0–26.2] |

238 | 78.0 [73.1–82.4] |

| Technology skills | 306 | 218 | 71.2 [66.0–76.1] |

79 | 25.8 [21.2–30.9] |

9 | 2.9 [1.5–5.3] |

| Ability to make adjustments to work | 305 | 141 | 46.2 [40.7–51.8] |

130 | 42.6 [37.2–48.2] |

34 | 11.1 [8.0–15.0] |

| Verbal communication ability | 305 | 24 | 7.9 [5.2–11.3] |

193 | 63.3 [57.8–68.5] |

88 | 28.9 [24.0–34.1] |

| Writing ability | 305 | 22 | 7.2 [4.7–10.5] |

168 | 55.1 [49.5–60.6] |

115 | 37.7 [32.4–43.2] |

| Ability to work on teams | 305 | 64 | 21.0 [16.7–25.8] |

206 | 67.5 [62.1–72.6] |

35 | 11.5 [8.3–15.4] |

| Tenure (time on the job) | 305 | 1 | 0.3 [0.0–1.5] |

43 | 14.1 [10.5–18.3] |

261 | 85.6 [81.3–89.2] |

| Health status | 304 | 187 | 61.5 [56.0–66.9] |

112 | 36.8 [31.6–42.4] |

5 | 1.6 [0.6–3.6] |

Note. CI: confidence interval.

These data were then analyzed to determine the influence of managerial experience on these ratings as this variable may be a mediating factor in managerial perceptions, in part perhaps because of the strong correlation it is likely to have with respondent age. Four groups of respondents were identified based on the four levels of managerial experience noted above: those with 5 or fewer years of managerial experience, those with more than 5 but less than 10 years of experience, those with between 10 and 20 years of experience, and those with more than 20 years of managerial experience. To test hypotheses concerning whether the experience level of the manager played a role in the ratings of importance of these worker-related factors or in the comparisons of older workers to younger workers on these factors, a series of Kruskal–Wallis tests was performed. Based on the ratings that were provided on each of the 13 worker-related factors listed in Table 3, mean ranks were computed for the four groups of managers. No significant differences between managerial groups in their ratings of importance were found for any of the 13 factors (all values of p > 0.05).

For each of these 13 worker-related factors, mean ranks were also computed for each of the managerial experience groups based on these respondents’ rankings of older workers as compared to younger workers. In these analyses, the category of worse/less was assigned the value of 1; the category of about the same was assigned the value of 2; and the category of better/more was assigned the value of 3. Significant differences between the managerial groups in their assessments of older workers as compared to younger workers were found for seven of the factors: maturity, χ2(3) = 19.7, p < 0.001; trustworthiness, χ2(3) = 11.28, p = 0.01; reliability, χ2(3) = 17.82, p < 0.001; independence, χ2(3) = 17.55, p = 0.001; writing ability, χ2(3) = 8.37, p = 0.039; ability to adjust, χ2(3) = 12.72, p = 0.005; and technology skills, χ2(3) = 17.51, p = 0.001. In each case, with the single exception of trustworthiness, the mean ranks increased with each increasing level of managerial experience. In the case of trustworthiness, managers with 10 to 20 years of experience had a higher mean rank than managers with more than 20 years of experience.

Further analysis using the Mann–Whitney U test was performed on each of these seven factors to determine which managerial groups, if any, significantly differed from one another. The results are summarized in Table 6. In the case of every worker-related factor for which a significant difference between managerial groups was found, the difference was in the direction of the managerial group with the higher level of experience favoring older workers over younger workers to a greater degree than did their less experienced managerial group counterparts.

TABLE 6.

Summary of Post Hoc Mann–Whitney U Testsa on Worker-Related Factors for Which Significant Differences in Level of Managerial Experience Were Found in Comparisons of Older and Younger Workersb

| Comparisons between Managerial Groups based on Level of Experience |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work-Related Factor | ≤5 years vs. >5, <10 years | ≤5 years vs. 10–20 years | ≤5 years vs. >20 years | >5, <10 years vs. 10–20 years | >5, <10 years vs. >20 years | 10–20 years vs. >20 years |

| Trustworthiness | nsc | −3.32, p = 0.001 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Reliability | ns | ns | −3.91, p < 0.001 | ns | −2.98, p = 0.003 | ns |

| Ability to work independently | ns | ns | −3.34, p = 0.001 | ns | −3.64, p < 0.001 | ns |

| Maturity | −2.71, p = 0.007 | −3.26, p = 0.001 | −3.85, p < 0.001 | ns | ns | ns |

| Technology skills | −3.26, p = 0.002 | −3.26, p = 0.001 | −4.15, p < 0.001 | ns | ns | ns |

| Ability to make adjustments | ns | ns | −3.47, p = 0.001 | ns | ns | ns |

| Writing ability | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

Test statistic values reported are z-scores.

In all cases, a significant result reflected a more favorable comparison of older workers as compared to younger workers by respondents with a greater number of years of managerial experience.

ns: nonsignificant based on p >.0083, the critical value derived from the Bonferroni adjusted alpha level of .05.

6. DISCUSSION

The primary goal of this article was to provide an appraisal of the prospects for employing older workers as at-home teleworkers. Although there is considerable literature related to telework and the concerns associated with an aging population and workforce, the employability of older workers as teleworkers has received almost no treatment. It is our contention that telework can address a number of the concerns associated with an aging workforce, in large part by virtue of its ability to accommodate many of the unique needs of older workers. At the same time, increasingly powerful and less expensive ICTs should enable a greater variety of work tasks to be performed from the home while affording a variety of benefits to organizations as well.

However, as was implied in the discussion of issues associated with telework, and especially managerial attitudes toward older workers, employing older workers as teleworkers represents a complex dynamic. There is evidence that organizations may be reluctant to invest in training older workers in new technologies (Freidberg, 2002; Villosio et al., 2008), which may reflect not only an economic perspective—there may be less opportunity to reap any benefits from the investment—but also attitudes about older people being less flexible and adaptive, and thus less willing to learn new skills. When one also considers the more general concerns that managers may have regarding telework, such as the inability to directly observe at-home workers, the potentially increased burden associated with shifting the emphasis from managing workers to managing worker performance, the need for training on how to manage teleworkers, and the ambiguity in a variety of legal aspects of telework, especially those that might concern the employer’s obligation to ensure the safety and health of their (older) employees who work at home, there exist a potentially large number of forces opposing the employability of older teleworkers.

From an empirical standpoint, our focus was on collecting data that might provide some indications concerning managers’ attitudes about employing older workers as teleworkers from the perspective of worker attributes that are conducive to selecting employees for this type of work arrangement. In this regard, a limitation of the study that should be noted was the absence of data on the entire sample of managers regarding the extent or nature of the experience that these managers had with teleworkers. Our questionnaire did ask “How would you describe your experience (i.e., your general interaction) with teleworkers in your company?” in terms of being “about none, very little, moderate, or extensive.” However, only respondents currently working for companies that were providing teleworking opportunities for their employees (229 of the 314 respondents) were asked this question. As many of the excluded managers may have had prior experience with teleworkers in previous employment, potentially valuable information may have been lost. In any case, controlling for prior experience in managing teleworkers (e.g., in assessing importance ratings) would have been difficult within our current analysis plan given the ordinal nature of the data. The assumption made was that the respondents were sufficiently competent, based on their managerial skills and knowledge, to judge the importance of the various worker-related attributes for teleworking performance. As emphasized below, managers with vastly different degrees of managerial experience were found to be consistent in their ratings of every one of these 13 attributes, suggesting that this assumption was reasonable.

Overall, the data indicated that trustworthiness, reliability, ability to work independently, and time management were the most important worker attributes to managers for deciding whether to allow a worker to telework. Other important attributes were adaptability and technology skills. The latter is particularly important with respect to older workers given that they typically have less experience with new technologies. Generally, these results are in line with research that suggests that constructs such as trust and dependability play an important role in a manager’s decision to allow a worker to telework. The fact that no significant differences in ratings were found between respondent groups indicates that managers at vastly different levels of experience were consistent in the relative importance attributed to each of these 13 variables.

In further examining these worker-related attributes from the perspective of comparisons between older and younger workers, although many of the responses were neutral, older workers were favored over younger workers for the attributes that the respondents considered most important for allowing a worker to telework: trustworthiness, reliability, ability to work independently, and time-management ability. However, younger workers were viewed more favorably than older workers with respect to the ability to work on teams and the ability to make adjustments, and overwhelmingly so with regard to technology skills. Also, significant differences between respondent groups based on level of managerial experience were found on 7 of the 13 worker-related attributes, including the attributes that were rated most highly. Further analysis of these results revealed a clear distinction between the least and most experienced managers on their comparisons of younger and older workers, with the most experienced managers consistently favoring older workers on each worker-related attribute to a greater degree than did the least experienced managers.

The findings based on comparisons between older and younger workers with respect to trustworthiness, reliability, ability to work independently, and time-management ability are especially noteworthy and overall paint a favorable picture for the employability of older teleworkers. However, the comparisons between older and younger workers on factors such as the ability to adjust, teamwork, and especially technology skills are not very encouraging. These assessments are typical of characterizations of older people as being inflexible and relatively poor at interacting or keeping up with technology. Thus there appear to be both positive and negative forces simultaneously in operation with respect to the potential influence of management.

Although research has shown that older people are willing to (and capable of) learning new technologies given adequate training and support, the results of this study suggest that many of the myths regarding older people in general extend to older workers, especially the beliefs of less experienced and presumably younger managers. If we are to be successful at employing older teleworkers, efforts are needed to educate managers to look past common myths concerning the abilities and tendencies of older workers. However, there are additional challenges as well. Organizations will need to better map out the types of work activities that can be performed as telework and, especially for companies in the private sector, establish programs dedicated to creating, managing, and assessing telework. They must also provide the instructional vehicles that would enable older workers to become trained in the relevant technologies; the necessary coaching and feedback for older workers to successfully perform their jobs while working exclusively from the home; and greater consideration to workspace design factors to which older people (as compared to younger workers) may be more sensitive. At the same time, older workers interested in teleworking from the home need to be educated on searching online to find such opportunities.

Finally, policies are needed at both the state and federal levels of government to promote telework opportunities for older workers, especially in the private sector, including the means for informing older people about telework opportunities (Eyster, Johnson, & Toder, 2008). It is also necessary that the vast array of federal labor and employment policies, which have been based primarily on working at a central location, be adapted to issues that can arise from working at home. These include the need to articulate the employer’s obligation for ensuring safe workplaces and liability for injury for at-home teleworkers, and the extent to which home-based work performance monitoring does not violate workers’ expectations of privacy (Potter, 2003). A variety of tax-related issues, including those governing the issuing of equipment to teleworkers, also need to be resolved, and states should consider giving companies tax credits for purchasing equipment that teleworkers would use in their homes as has been done in Oregon (Oregon Department of Energy, 1995). The impact of these legislative policies should not be underestimated. As stated by Potter (2003): “New policies need to be crafted... These kinds of legal questions simply reinforce managerial resistance to telecommuting” (p. 80).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health (Grant P01 AG17211-0252). We gratefully acknowledge the advice provided by Martin Rome of Experience Works, Inc., and James Grosch of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, in development of the questionnaire.

7. APPENDIX 1

Two questions from the telework questionnaire designed to address the employability of older workers as home-based teleworkers.

Contributor Information

Joseph Sharit, Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL 33124, USA.

Sara J. Czaja, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL 33136, USA

Mario A. Hernandez, Center on Aging, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL 33136, USA

Sankaran N. Nair, Center on Aging, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL 33136, USA

References

- Brown JS, Duguid P. The social life of information. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Buck Consultants. The Real Talent Debate: Will Aging Boomers Deplete the Workforce? 2007 Retrieved May 2008 from http://www.cvworkingfamilies.org/system/files/TalentDebate.pdf.

- Buessing A. Telework. In: Karwowski W, editor. International encyclopedia of ergonomics and human factors. London: Taylor & Francis; 2000. pp. 1723–1725. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo E. Work opportunities for older Americans series 2. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College; 2006. Does working longer make people healthier and happier? [Google Scholar]

- Charness N, Czaja SJ, Sharit J. Age and technology for work. In: Shultz KS, Adams GA, editors. Aging and work in the 21st century. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. pp. 225–249. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman L. Baby boom to bay bust: Flexible work options for older workers. Benefits Quarterly. 1998;14:18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Czaja SJ, Charness N, Fisk AD, Hertzog C, Nair SN, Rogers WA, Sharit J. Factors predicting the use of technology: Findings from the Center for Research and Education on Aging and Technology Enhancement (CREATE) Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:333–352. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dychtwald K, Erickson TJ, Morison R. Workforce crisis: How to beat the coming shortage of skills and talent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison NB. Telework and social change. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Foundation paper No. 1. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2002. Quality of work and employment in Europe: Issues and challenges. Available at: http://www.eurofound.europ.eu/publications/htmlfiles/ef0212.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Eyster L, Johnson RW, Toder E. Final Report (January) by the Urban Institute for the U.S. Department of Labor. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2008. Current strategies to employ and retain older workers. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Computer Week (FCW.com) GSA clarifies telework rules for managers. 2008 Retrieved June 23, 2008, from http://www.fcw.com/print/1211/news/92766-1.html.

- Finkelstein LM, Burke MJ, Raju NS. Age discrimination in simulated employment contexts: An integrative analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1995;80:652–663. [Google Scholar]

- Fisk AD, Rogers WA, Charness N, Czaja SJ, Sharit J. Designing for older adults: Principles and creative human factors approaches. 2. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen KI, Scharlach AE. Caregiving and employment: The impact of workplace characteristics on role strain. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 1997;28(4):3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg L. The labor supply effects of the social security earnings test. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 2000;82(1):48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg L. The impact of technological change on older workers: Evidence from data on computer use. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 2002;56:511–529. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon RA, Arvey RD. Age bias in laboratory and field settings: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2004;34:468–492. [Google Scholar]

- Handy C. Trust and the virtual organization. Harvard Business Review. 1995;73(3):40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Himes CL. Elderly Americans. Population Bulletin. 2001;56:3–41. [Google Scholar]

- Illegems V, Verbeke A. Telework: What does it mean for management? Long Range Planning. 2004;37:319–334. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RW, Steuerle E. Promoting work at older ages: The role of hybrid pension plans in an aging population. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance. 2004;3(3):315–337. [Google Scholar]

- Kite ME, Stokdale GD, Whitley BE., Jr Attitudes toward younger and older adults: An updated meta-analytic review. Journal of Social Issues. 2005;61:241–266. [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer KHE. Designing for older people. Ergonomics in Design. 2007;14(4):25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kurland NB, Bailey DE. Telwork: The advantages and challenges of working here, there, anywhere, anytime. Organisational Dynamics. 1999;28:53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey J. Issue Brief. 33. Boston: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College; 2005. Jul, Do older workers face discrimination? 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Personnel Management. Telework: A management priority, a guide for managers, supervisors, and telework coordinators. Washington, DC: United States Office of Personnel Management; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Oregon Department of Energy. Telecommuting: An option for Oregon workers with disabilities. Salem, OR: Oregon Department of Energy; May, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Park DC, Schwartz N. Cognitive aging: A primer. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Patrickson M. Teleworking: Potential employment opportunities for older workers? International Journal of Manpower. 2002;23:704–715. [Google Scholar]

- Perry EL, Kulik CT, Bourhis AC. Moderating effects of personal and contextual factors in age discrimination. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1996;81:628–647. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.81.6.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Internet & American Life Project. Online Health Search 2006. 2006 Retrieved March 26, 2008, from http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIPOnlineHealth2006.pdf.

- Potter EE. Telecommuting: The future of work, corporate culture, and American society. Journal of Labor Research. 2003;24:73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds T, Brusseau D. Cyberlane commuter. South Pasadena, CA: iLAN Systems; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Martire LM. Caregiving and employment. In: Czaja SJ, Sharit J, editors. Aging and work: Issues and implications in a changing landscape. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharit J, Czaja SJ, Hernandez M, Yang Y, Perdomo D, Lewis JL, Lee C, Nair S. An evaluation of performance by older persons on a simulated telecommuting task. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2004;59B(6):305–316. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.6.p305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toossi M. A new look at long-term labor force projections to 2050. Monthly Labor Review. 2006 November [Google Scholar]

- Villosio C, Di Pierro D, Giordanengo A, Pasqua P, Richiardi M. Working conditions of an ageing workforce. Dublin, Ireland: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Warr P. Job performance and the ageing workforce. In: Chmiel N, editor. Work and organizational psychology. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2000. pp. 408–423. [Google Scholar]

- Warr P, Pennington J. Age and employment: Policies and practices. London: Institute of Personnel Management; 1993. Views about age discrimination and older workers. [Google Scholar]

- WFC Resources. Coming soon: Demographic craziness. 2008 Retrieved July 2008, from http://www.wfcresources.com/Work-lifeClearinghouse/UpDates/ud0013.Htm.