Abstract

Several in vitro studies have emphasized the importance of toll-like receptor/myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) signaling in the inflammatory response to Streptococcus pyogenes. Since the extent of inflammation has been implicated in the severity of streptococcal diseases, we have examined here the role of toll-like receptor/MyD88 signaling in the pathophysiology of experimental S. pyogenes infection. To this end, we compared the response of MyD88-knockout (MyD88−/−) after subcutaneous inoculation with S. pyogenes with that of C57BL/6 mice. Our results show that MyD88−/− mice harbored significantly more bacteria in the organs and succumbed to infection much earlier than C57BL/6 animals. Absence of MyD88 resulted in diminished production of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-12, interferon-γ, and tumor necrosis factor-α as well as chemoattractants such as monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and Keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC), and hampered recruitment of effector cells involved in bacterial clearance (macrophages and neutrophils) to the infection site. Furthermore, MyD88−/− but not C57BL/6 mice exhibited a massive infiltration of eosinophils in infected organs, which can be explained by an impaired production of the regulatory chemokines, gamma interferon-induced monokine (MIG/CXCL9) and interferon-induced protein 10 (IP-10/CXCL10), which can inhibit transmigration of eosinophils. Our results indicate that MyD88 signaling targets effector cells to the site of streptococcal infection and prevents extravasation of cells that can induce tissue damage. Therefore, MyD88 signaling may be important for shaping the quality of the inflammatory response elicited during infection to ensure optimal effector functions.

Streptococcus pyogenes represents one of the most frequent causes of mild infection of the upper respiratory tract and the skin with the potential to cause life-threatening invasive diseases such as necrotizing fasciitis and septicemia.1 Although severe streptococcal diseases occur in only a small percentage of cases, they are an important cause of morbidity and mortality. Specific manifestations of streptococcal infections are dictated by the complex interplay of bacterial virulence factors and the host immune components. Deciphering the complexities of the host response to invasive S. pyogenes will greatly facilitate the use of more appropriate targeted therapies for affected patients in the future.

Pivotal components of the host innate immune response to pathogens are the toll-like receptors (TLRs). TLRs recognize the presence of microbial pathogens via the detection of pathogen-associated molecular patterns such as lipopolysaccharide, lipoproteins, peptidoglycans, double-stranded RNA, CpG DNA, and flagellin.2,3,4,5,6 The recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by TLRs leads to signaling events resulting in the coordinated activation of transcription factors that induce the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and other inflammatory mediators.7 Myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) is the central signaling adaptor molecule that mediates cellular stimulation from most of TLRs.8,9 MyD88 is critical for the TLR-mediated activation of transcription factors and thus for the induction of proinflammatory molecules.8,9

It has been demonstrated in previous studies that MyD88 signaling is essential for the host defense against microbial infections in experimental murine systems10,11,12,13 as well as in humans.14,15,16 The importance of the TLR signaling in human diseases was highlighted in recent clinical studies in which the authors examined patients lacking interleukin (IL)-1 receptor–associated kinase 4, which is selectively recruited to TLRs and IL-1 receptors by MyD88.14,15,16 MyD88-deficient patients exhibit an impaired response to most of TLRs ligands as well as to IL-1 and display a life-threatening but narrow and transient predisposition to infection, apparently restricted to pyogenic bacterial diseases.14,15

Although optimal stimulation of TLRs is critical for triggering inflammatory responses that result in pathogen eradication, in some cases, excessive TLR activation may instead contribute to detrimental inflammation. Thus, mice deficient in MyD88 expression have been reported to be more resistant than normal animals to lethal shock after administration of a high-dose of lipopolysaccharide17 or after induction of polymicrobial sepsis.18 The beneficial effect of MyD88 ablation in this experimental setting seems to rely on the attenuation of the hyperinflammatory response and concomitant reduced tissue injury.17,18 Furthermore, a dual role of MyD88 has been demonstrated in an experimental model of group B streptococcal infection where MyD88 was essential for antimicrobial defenses during the initial infection but it contributed to lethality in the presence of overwhelming sepsis.19

In the particular case of S. pyogenes, we have recently demonstrated the absolute requirement of MyD88 for the up-regulation of maturation markers and the production of inflammatory cytokines in S. pyogenes-stimulated dendritic cells.20 In addition, Gratz et al21 have also reported that production of proinflammatory cytokines by macrophages after in vitro stimulation with S. pyogenes was completely dependent on MyD88. In view of the critical importance of MyD88 signaling in the immune response to S. pyogenes, our objective for this study presented here was to obtain further insights into the functional significance of this central adaptor molecule in regulating the host response to S. pyogenes by using an experimental mouse model of skin infection. Our results demonstrate that MyD88 signaling is decisive for triggering a rapid innate immune response against S. pyogenes that operates at two levels: (1) by inducing the up-regulation of inflammatory mediators that triggers chemotaxis of cells critically involved in bacterial clearance such as neutrophils and macrophages to the site of infection; and (2) by promoting the expression of regulatory chemokines such as MIG/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10, shown to inhibit the recruitment of other cell types with potential detrimental effects (eg, eosinophils). In the absence of MyD88, the inflammatory response elicited in response to S. pyogenes shifted from a protective neutrophil/macrophage-mediated to a destructive eosinophil-dominated cellular infiltrate. Our data highlight a role of MyD88 in shaping the quality of the inflammatory response elicited during S. pyogenes infection.

Materials and Methods

Bacteria and Culture Conditions

The S. pyogenes strain KTL3 (M1 type) was initially isolated from the blood of a patient with streptococcal bacteremia. Stock cultures were maintained at −70°C and cultured at 37°C in Todd-Hewitt broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK), supplemented with 1% yeast extract. Bacteria were collected in Mid-Log-phase, washed twice with sterile PBS, diluted to the required inoculums, and the number of viable bacteria was determined by counting colony-forming units (CFU) after plating on blood agar plates containing 5% sheep blood (GIBCO, Paisley, UK).

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Harlan-Winkelmann (Borchen, Germany). MyD88−/− mice with a C57BL/6 genetic background were obtained from either the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology (Berlin, Germany) or from Lund University (Lund, Sweden). Mice were housed in a pathogen-free animal facility and maintained under standard conditions according to institutional guidelines. All experiments were approved by the appropriate ethical board (Niedersächsisches Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit, Oldenburg, Germany).

Experimental Model of S. pyogenes Infection

MyD88−/− and C57BL/6 mice were injected subcutaneously with the indicated amount of S. pyogenes strain KTL3 as previously described.22 Briefly, mice were anesthetized with Isoba (Essex, Munich, Germany) and infected subcutaneously with S. pyogenes in 100 μl of PBS at the right front flank. Infected mice were monitored for survival or sacrificed by CO2 inhalation at the indicated time intervals to measure bacterial burdens in blood and systemic organs. For calculation of 50% lethal dose, groups of 10 mice were subcutaneously inoculated with different amounts of S. pyogenes, ranging from 104 to 5 × 107 CFU and mortality was scored over a period of 15 days. The 50% lethal dose was calculated by using the method of Reed and Muench.23

Determination of Biochemical Plasma Parameters

The plasma levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, creatin phosphokinase, and lactate dehydrogenase were determined by using the analyzer Olympus AU400 (Olympus Europe GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cytokines and Chemokines Profile

Serum cytokines profile was determined at 6, 12, and 20 hours of infection by using the Mouse Cytokine Twenty Plex LMC0006 (Biosource Europe, Nivelles, Belgium) in conjunction with the Luminex 100 IS Total System (Oosterhout, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In Vitro Infection of Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages

Bone marrow-derived macrophages were generated as previously described24 and infected with S. pyogenes at a multiplicity of infection of 10 bacteria per macrophage for 1 hour. Monolayers were washed to remove unbound bacteria and further incubated in the presence of gentamicin (100 μg/ml) at 37°C in 5% CO2 to kill extracellular bacteria. After different periods of time, cells were washed and disrupted with dH2O to release intracellular bacteria. The resulting suspension was serially diluted and bacterial numbers were determined after plating onto blood agar.

Control experiments were performed to confirm that gentamicin did not penetrate inside the macrophages during the incubation time (Supplemental Figure S1, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). For this purpose, bone marrow-derived macrophages were seeded onto four-well tissue culture plates and incubated for 24 hours in medium alone or in the presence of 100 μg/ml of either gentamicin or erythromycin. Erythromycin has been previously described to be capable to permeabilize eukaryotic cells. After removing the culture supernatant, macrophages were thoroughly washed with sterile PBS, resuspended in 100 μl of ice-cold 0.1% Triton X-100 and incubated for 10 minutes at −20°C. After centrifugation, 5 μl of the resulting supernatants was dropped onto blood agar plates on which a lawn of S. pyogenes was seeded. The plates were incubated in 5% CO2 for 18 hours at 37°C.

Isolation and Infection of Bone Marrow-Derived Neutrophils

Mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, and their femurs and tibias were flushed with PBS. After hypotonic lysis of erythrocytes, cells were resuspended in HBSS, and the cell suspension was layered over a Percoll (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) gradient and centrifuged for 30 minutes at 1300 × g. The resulting neutrophil pellet was washed in PBS and suspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium. Neutrophils were counted on a Neubauer chamber, and the purity of the fractionated cell population was confirmed by flow cytometry examination. For determination of phagocytosis and killing of S. pyogenes, 5 × 105 neutrophils were preincubated with 1 μg/ml of PMA (Sigma) for 30 minutes and were washed and infected with 5 × 106 bacteria for 1 hour at 37°C, 5% CO2. Gentamicin (100 μg/ml) was added to kill extracellular bacteria and infected neutrophils were centrifuged 1 hour, 3 hours, and 5 hours thereafter. The cell pellet was then extensively washed and disrupted with dH2O plus Triton X-100 (0.1%) to release intracellular bacteria. The resulting suspension was serially diluted and the bacterial numbers were determined after plating onto blood agar.

Generation of Skin Air Pouches

To generate air pouches, animals were anesthetized and 0.9 ml of air plus 100 μl of a suspension containing 5 × 107 CFU of S. pyogenes were injected subcutaneously on the back of the mouse. After 14 hours, mice were sacrificed, the air pouches were washed after incision of the skin, and the total number of cells was counted by using a hemocytometer. Cells were then stained with antibodies against Gr-1, CD19, CD11c, CD11b, CD4 or CD8a (PharMingen, San Diego, CA) and analyzed in a FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Histopathological Examination

Tissues were fixed in 4% formaldehyde solution, embedded in paraffin, and then cut into 3-μm-thick sections. Sections were stained with H&E and were analyzed by using an Olympus Bx51 microscope. The degree of tissue eosinophilia was determined as previously described.25 Briefly, stained tissue sections were examined at ×100 magnification, with a 10 × 10-mm reticulate present in the eyepiece. The total number of eosinophils present within this grid was determined as the eosinophil counts per high-power field. A total of five high-power fields were assessed by three independent individuals.

Eosinophil Peroxidase Assay

Indirect quantification of eosinophils in tissue was performed by using an eosinophil peroxidase (EPO) assay as previously described.26 Briefly, lungs were flushed through the pulmonary artery, homogenized in 2 ml of ice-cold 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH = 8) containing 0.1% Triton X-100, exposed to five freeze-thaw cycles, and centrifuged at 1600 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C. The EPO activity in the supernatant was measured based on the oxidation of o-phenylenediamine by EPO in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. It has been previously reported that o-phenylenediamine is a specific substrate for EPO, and that the assay is not affected by neutrophil myeloperoxidase in murine systems.26 The substrate solution consists of 10 mmol/L o-phenylenediamine (Sigma) in 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH = 8) and 4 mmol/L hydrogen peroxide (Sigma). Substrate solution (100 μl) was added to lung supernatant samples (50 μl) in a 96-well microplate and incubated at room temperature for 60 minutes before the reaction was stopped by addition of 50 μl of 4 M sulfuric acid. The absorbance was then measured at 492 nm.

Bronchoalveolar Lavage

For harvesting cells from the brochoalveolar lavage, mice were terminally anesthetized, the thoracic cavity was opened, and the lungs were exposed. A tube was inserted in the trachea and bronchoalveolar lavage was conducted with 2 × 0.5 ml of PBS containing complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The lavage was centrifuged and the supernatants were stored at −80°C until cytokine analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by using Excel 2000 (Microsoft Office; Microsoft, Redmond, WA) or GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Survival data were analyzed with Kaplan-Meier survival plots, followed by Long-rank test. The significance of differences between the values of an experimental group and those of the control group was determined by use of a variance analysis (F test). Significance levels were set at P < 0.05.

Results

Marked Susceptibility of MyD88−/− Mice to S. pyogenes Infection

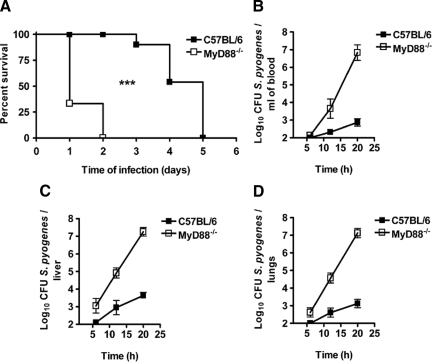

It has been previously shown that MyD88 is required for the recognition of S. pyogenes by innate immune cells in vitro.20,21 Here, we have evaluated the functional role of MyD88 signaling in the pathogenesis of S. pyogenes in vivo by using a previously described22 murine model of skin infection. In this experimental infection model, S. pyogenes is applied subcutaneously at the right front flank and disseminate from the skin to systemic organs. C57BL/6 and MyD88−/− mice were subcutaneously infected with 5 × 107 CFU of S. pyogenes and monitored for survival. As shown in Figure 1A, all MyD88−/− mice rapidly succumbed to infection, dying between 1 and 2 days after bacterial inoculation, whereas the median survival time of C57BL/6 animals was 5 days. Even when the mice were inoculated with a lower bacterial dose (104 CFU), MyD88−/− mice were still much more susceptible than C57BL/6 mice to S. pyogenes infection (Supplemental Figure S2, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Using the method published by Reed and Muench,23 we determined the 50% lethal dose to be approximately 2 × 106 CFU for C57BL/6 mice and less than 104 CFU for MyD88−/− mice.

Figure 1.

Enhanced susceptibility of MyD88−/− mice to infection with S. pyogenes. A: Survival curves of C57BL/6 (black symbols) and MyD88−/− (white symbols) mice after subcutaneous infection with 5 × 107 CFU of S. pyogenes. Groups of 10 MyD88−/− or C57BL/6 mice were infected with 5 × 107 CFU of S. pyogenes and survival was monitored over time. Comparison of survival curves was performed by using the Long-rank test. ***P < 0.001. Kinetics of bacterial growth in blood (B), liver (C), and lungs (D) of C57BL/6 (black symbols) and MyD88−/− (white symbols) after subcutaneous infection with 5 × 107 CFU of S. pyogenes are shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD of a minimum of 10 mice per time point and are the compilation of three independent experiments.

To determine whether the reason for the accelerated mortality of MyD88−/− mice was due to uncontrolled bacterial multiplication, bacterial burdens were measured in blood, livers, and lungs of S. pyogenes-infected mice at increasing times after bacterial inoculation. MyD88−/− mice exhibited a profound deficiency in their ability to control bacterial growth, with approximately 104 higher amount of bacteria in blood (Figure 1B), livers (Figure 1C), and lungs (Figure 1D) compared with the bacterial burdens in C57BL/6 animals at 20 hours of infection.

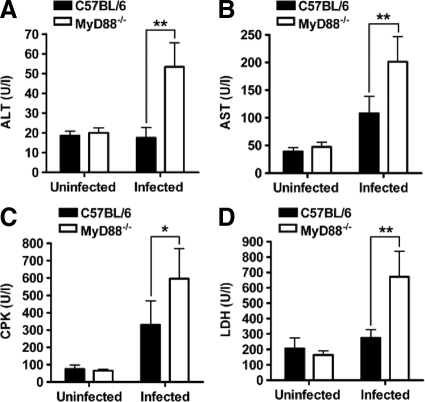

In addition, significantly higher plasma levels of alanine aminotransferase (Figure 2A), aspartate aminotransferase (Figure 2B), creatin phosphokinase (Figure 2C), and lactate dehydrogenase (Figure 2D) were detected in MyD88−/− than in C57BL/6 mice at 20 hours after inoculation with S. pyogenes. The results suggest a higher degree of liver (alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase), heart/lung (lactate dehydrogenase), and muscle (creatin phosphokinase) damage in MyD88−/− animals than in C57BL/6 mice. Therefore, ablation of MyD88 signaling enhanced significantly the severity of infection caused by S. pyogenes in mice.

Figure 2.

Serum levels of biochemical markers of organ damage in S. pyogenes-infected MyD88−/− and C57BL/6 mice. The levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT, A), aspartate aminotransferase (AST, B), creatin phosphokinase (CPK, C), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, D) were determined in the plasma of C57BL/6 (black bars) and MyD88−/− (white bars) mice at 20 hours of infection. The plasma levels of these parameters in uninfected mice are included for comparison. Each bar represents the mean ± SD value of five mice. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Similar results were obtained from three different experiments.

MyD88 Is Required for the Early Inflammatory Cytokine Response to S. pyogenes

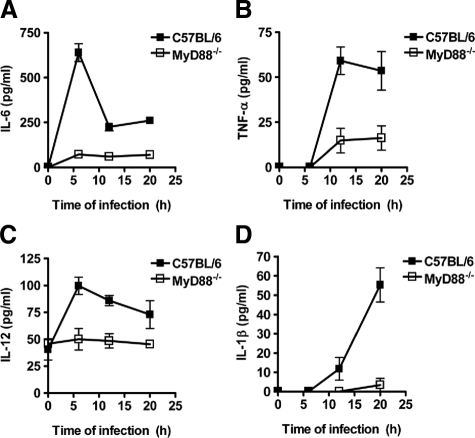

MyD88 signaling has been reported to be required for the production of certain cytokines by innate immune cells such as dendritic cells20 and macrophages21 in response to S. pyogenes. Therefore, we next quantified the levels of cytokines such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in serum of MyD88−/− and C57BL/6 mice at 6, 12, and 20 hours after subcutaneous inoculation with 5 × 107 CFU of S. pyogenes. Only the inflammatory cytokines IL-6 (Figure 3A), TNF-α (Figure 3B), IL-12 (Figure 3C), and IL-1β (Figure 3D) were found to be produced in response to infection. IL-6 (Figure 3A) and IL-12 (Figure 3C) were induced as early as 6 hours postinfection, whereas TNF-α (Figure 3B) and IL-1β (Figure 3D) were not detected until 12 hours following bacterial inoculation. Notably, the levels of these cytokines were significantly reduced in the serum of MyD88−/− mice compared with C57BL/6 animals independently of the time of infection (Figure 3). These results indicate that the production of inflammatory cytokines during infection with S. pyogenes is primarily controlled by MyD88 signaling.

Figure 3.

Impaired production of inflammatory cytokines in S. pyogenes-infected MyD88−/− mice. C57BL/6 (black symbols) and MyD88−/− (white symbols) mice were infected subcutaneously with 5 × 107 CFU of S. pyogenes, and serum samples were obtained at increasing times of infection for the evaluation of the systemic production of IL-6 (A), TNF-α (B), IL-12 (C), and IL-1β (D). Each plot shows the mean ± SD value for 9 to 15 mice of the indicated genotype obtained from three separate experiments.

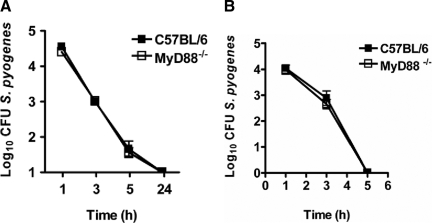

MyD88 Deficiency Does Not Influence Phagocytosis or Killing of S. pyogenes by Phagocytic Cells

Resident macrophages in tissues and neutrophils, which migrate from the blood to the site of infection, constitute the primary line of innate defense against S. pyogenes. For this reason, we asked whether a defect in phagocytosis and killing of S. pyogenes by these effector cells might underlie the enhanced susceptibility of MyD88−/− mice. To determine whether deletion of MyD88 would affect the uptake and/or the intracellular bactericidal killing by macrophages, bone marrow-derived macrophages from MyD88−/− and C57BL/6 mice were infected with S. pyogenes, and the viability of internalized bacteria was determined overtime by using a gentamicin-protection assay. The results presented in Figure 4A show that macrophages from MyD88−/− mice were as capable as those from C57BL/6 to phagocytose and kill S. pyogenes. In addition, MyD88 did not seem to contribute to phagocytosis and killing of S. pyogenes by neutrophils (Figure 4B). Therefore, similar to the observations previously reported for dendritic cells,20 MyD88−/− macrophages and neutrophils demonstrated an unaltered capacity to uptake and kill S. pyogenes.

Figure 4.

Phagocytosis and killing of S. pyogenes by macrophages and neutrophils isolated from C57BL/6 or MyD88−/− mice. A: Kinetics of S. pyogenes killing by macrophages isolated from C57BL/6 (black symbols) or MyD88−/− (white symbols) mice. Each point represents the mean ± SD value of three independent experiments. B: Kinetic of S. pyogenes killing by neutrophils isolated from bone marrow of C57BL/6 (black symbols) or MyD88−/− (white symbols) mice. Each point represents the mean ± SD value of three independent experiments.

Impaired Neutrophil Recruitment in S. pyogenes-Infected MyD88−/− Mice

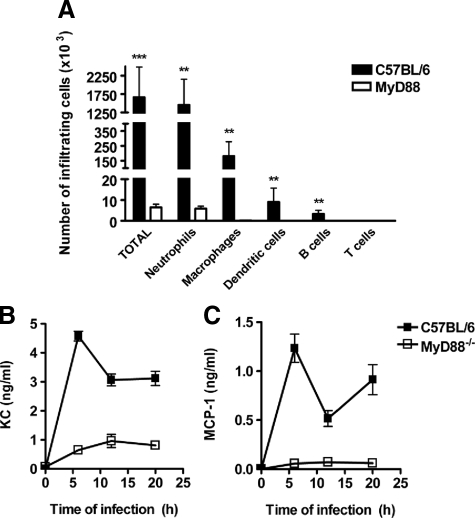

In view of the MyD88-independent uptake and killing of S. pyogenes, added to the previously demonstrated normal migration abilities of MyD88-deficient phagocytic cells,18 we hypothesized that a defect in the early recruitment of macrophages and neutrophils might underlie the increased susceptibility of MyD88−/− mice to S. pyogenes. To demonstrate this assumption, air pouches were generated in MyD88−/− and C57BL/6 mice by using 0.9 ml of air plus 100 μl of a suspension containing 5 × 107 CFU of S. pyogenes. Mice were sacrificed after 14 hours of bacterial inoculation; air pouch exudates were counted and analyzed by flow cytometry. While S. pyogenes infection led to a significant increase of inflammatory cells infiltrating the air pouches of C57BL/6 mice, the amount of infiltrating inflammatory cells was significantly attenuated in the absence of MyD88 (Figure 5A). Neutrophils were the predominant cell type (Gr-1high/CD11b+) followed by macrophages (CD11b+/Gr-1−), dendritic cells (CD11c+), and a few B cells (CD19+) (Figure 5A). These results clearly indicate that MyD88−/− mice exhibit an impaired ability to recruit inflammatory effector cells to the local site of S. pyogenes infection.

Figure 5.

MyD88−/− mice display impaired production of chemoattractants and recruitment of inflammatory macrophages and neutrophils into the site of S. pyogenes infection. A: Air pouches were generated in C57BL/6 (black bars) and MyD88−/− (white bars) mice as described in Materials and Methods. The total number of recruited cells as well as the numbers of macrophages (Gr-1−/Mac-1+), neutrophils (Gr-1+/Mac-1+), dendritic cells (CD11c+), B cells (CD19+), and T cells (CD4+ and CD8+) recruited into the air pouches in response to S. pyogenes infection are shown. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Kinetics of KC (B) and MCP-1 (C) appearance in the serum of C57BL/6 (black symbols) and MyD88−/− (white symbols) mice during the course of S. pyogenes infection. Each plot shows the mean ± SD value for 9 to 15 mice of the indicated genotype. Data are the compilation of three separate experiments.

As secretion of chemokines is responsible for the inflammatory cell trafficking toward the sites of infection, we next determined the serum levels of KC, a chemokine involved in the recruitment of neutrophils, and MCP-1, a chemokine involved in the recruitment of macrophages, in S. pyogenes-infected MyD88−/− and C57BL/6 mice at 6, 12, and 20 hours of infection. The results demonstrate that S. pyogenes elicited high levels of KC and MCP-1 in C57BL/6 mice and peak levels were detected at 6 hours of infection. Thereafter, the levels of both KC (Figure 5B) and MCP-1 (Figure 5C) appeared to undulate but remain high after the initial peak. In contrast, S. pyogenes infection induced significantly lower release of KC (Figure 5B) in MyD88−/− mice and only a marginal increased in MCP-1 (Figure 5C).

Together, these results suggest that rapid production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines responsible for the recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages to the local infection sites is MyD88-dependent. In the absence of MyD88, S. pyogenes multiplies without restriction due to the shortage of effector cells responsible for bacterial clearance.

Aberrant Inflammatory Response of MyD88−/− in Response to S. pyogenes Infection

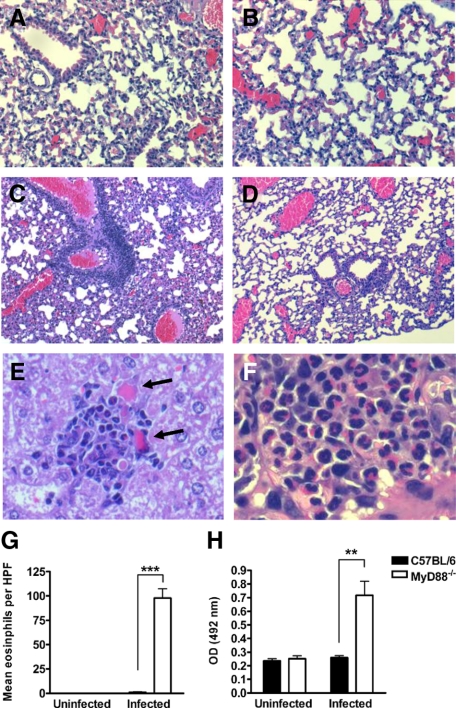

To get further insights into the pathological consequences of MyD88 deficiency, we performed a histopathological examination of the lungs and livers of infected MyD88−/− and C57BL/6 mice at 20 hours after bacterial inoculation. Lungs of infected MyD88−/− mice revealed a massive cellular infiltration, predominantly perivascular but also peribronchial with prominent septal thickening and edema formation (Figure 6C). In contrast, lungs of infected C57BL/6 mice exhibited fewer signs of pathology at this time of infection with quite intact alveolar structure (Figure 6D). Lung sections of uninfected MyD88−/− and C57BL/6 mice are shown in Figure 6, A and B, respectively. Inflammatory infiltrates were also present in the liver of infected MyD88−/− mice (Figure 6E) with areas of tissue destruction in the vicinity of the inflammatory cells (Figure 6E, arrows). In contrast, the livers of infected C57BL/6 mice had no signs of histological damage (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Exacerbated development of pathology in S. pyogenes-infected MyD88−/− mice. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were prepared from C57BL/6 and MyD88−/− animals at 20 hours after subcutaneous inoculation with S. pyogenes and stained with H&E. The representative sections shown are from uninfected MyD88−/− lung tissue (A), uninfected C57BL/6 lung tissue (B), S. pyogenes-infected MyD88−/− lung tissue (C and F), S. pyogenes-infected C57BL/6 lung tissue (D), and S. pyogenes-infected MyD88−/− liver tissue (E). The sections were photographed with a ×10 objective for C and D, ×20 objective for A and B, ×40 objective for E, and ×60 for F. Arrows in E indicate areas of tissue destruction. G: Mean eosinophil numbers in lung tissue of infected wild-type or MyD88−/− mice at 20 hours after subcutaneous inoculation with S. pyogenes. Quantification was performed as described in Materials and Methods. H: EPO activity in lung homogenates of C57BL/6 and MyD88−/− mice at 20 hours after subcutaneous inoculation with S. pyogenes. Homogenates of uninfected lungs were used as controls. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of six mice. Data are the compilation of two separate experiments. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; HPF = high-power field.

The massive infiltration of inflammatory cells revealed by the histopathological examination of tissue from infected MyD88−/− mice seems to be somehow inconsistent with the impaired ability of these mice to recruit macrophages and neutrophils into the site of infection. A closer examination of the inflammatory cells infiltrating in livers (Figure 6E) and lungs (Figure 6F) of infected MyD88−/− mice shows that these inflammatory cells were neither neutrophils nor macrophages but rather cells with brilliant red-pink cytoplasm and bi-lobed purple-blue nucleus typical of eosinophils. This red stain is associated with the intensely basic granules in the cytoplasm of these cells. Direct microscopic cell counting of lung tissue eosinophilia was performed as described in Materials and Methods and the results shown in Figure 6G. Whereas a high number of eosinophils were counted in the lung sections of infected MyD88−/− mice, eosinophils were completely absent in the inflammatory infiltrates present in the lungs of infected C57BL/6 mice (Figure 6G). The amount of eosinophils was also indirectly assessed by determining the activity of EPO, one of the most abundant granule proteins in eosinophils, in S. pyogenes-infected lung tissue isolated from MyD88−/− and C57BL/6 mice at 20 hours of infection. Lung tissue from uninfected mice was used as a control. Results in Figure 6H show that EPO activity is only detectable in tissue isolated from infected MyD88−/− mice.

MyD88 is Required for the Production of Eosinophil-Regulatory Chemokines MIG/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 during S. pyogenes Infection

The generation and recruitment of eosinophils is tightly regulated and has been reported to be influenced by the local expression of eosinophil chemoattractants such as eotaxins in the affected tissue.27 Therefore, we first determined whether eosinophil recruitment in the organs of S. pyogenes-infected MyD88−/− mice was linked to local production of eotaxins. For this purpose, expression of eotaxin-1 and eotaxin-2 was determined in the bronchoalveolar lavage of C57BL/6 and MyD88−/− mice after 20 hours of infection. Eotaxins were not expressed in detectable concentrations in the lungs of C57BL/6 or MyD88−/− mice before or after infection with S. pyogenes. Other potential eosinophil chemoattractants (IL-4 and IL-5) were also under the detection level (data not shown). These results indicate that recruitment of eosinophils in the organs of S. pyogenes-infected MyD88−/− mice is not promoted by the local expression of molecular signals.

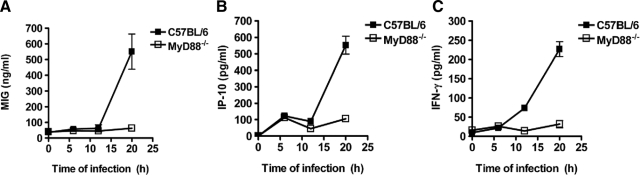

An additional mechanism reported to regulate eosinophil transmigration is based in the production of naturally occurring chemokine antagonists. These chemokines exert inhibitory activity by acting as competitive antagonists for a variety of receptors.28,29,30,31,32 Among these regulatory chemokines, MIG/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 have been shown to have the ability to block eosinophil chemoattraction and function.28,30 As the inhibitory action exerted by these chemokines on eosinophil recruitment into tissue depends on systemic rather than local expression,28 we next determined whether the serum levels of MIG/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 differed between S. pyogenes-infected C57BL/6 and MyD88−/− mice. To establish the time at which the levels of these chemokines are elevated in serum during infection, kinetic data were obtained at 6, 12, and 20 hours after bacterial inoculation. The levels of MIG (Figure 7A) and IP-10 (Figure 7B) were strongly increased in serum of C57BL/6 mice at 20 hours of infection. The levels of MIG did not significantly change in MyD88−/− mice in response to infection (Figure 7A), whereas the level of IP-10 increased only slightly (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Decreased production of regulatory chemokines in MyD88−/− mice during infection with S. pyogenes. C57BL/6 (black symbols) and MyD88−/− (white symbols) mice were infected subcutaneously with 5 × 107 CFU of S. pyogenes, and serum samples were obtained at increasing times of infection for the evaluation of the systemic production of MIG (A), IP-10 (B), and IFN-γ (C). Each plot shows the mean ± SD value for 9 to 15 mice and they are the compilation of three separate experiments.

MIG/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 are primarily induced by interferon-γ (IFN-γ).33 Determination of the levels of IFN-γ in infected mice demonstrated that S. pyogenes elicited high levels of IFN-γ only in C57BL/6 mice (Figure 7C). These levels tended to occur at 12 hours of infection and continued to increase until 20 hours (Figure 7C). Increases in serum IFN-γ levels were not observed in MyD88−/− mice (Figure 7C).

Discussion

Based on previous in vitro studies,20,21 MyD88 has been suggested to be involved in the response of innate immune cells to S. pyogenes. To determine the relevance of these in vitro observations to the pathogenesis of S. pyogenes in vivo, we have investigated here the impact of MyD88 deficiency on host resistance to S. pyogenes in a mouse model of infection. The results presented in this study show that MyD88−/− mice have a significantly increased susceptibility to S. pyogenes infection when compared with C57BL/6 animals. The increased susceptibility was demonstrated by enhanced bacterial proliferation in infected organs, faster development of pathology, and accelerated mortality. In addition, MyD88−/− mice were severely impaired in the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-12, shown to be important determinants for protection against S. pyogenes.34,35 The recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages to the site of infection was also significantly attenuated in MyD88−/− mice when compared with the C57BL/6 animals, which agreed with the finding that the expression of chemoattractants for KC and MCP-1 was strongly diminished in the former mice. This can explain, at least in part, the increased susceptibility of MyD88−/− mice since macrophages and neutrophils have been shown to be required for normal resistance to S. pyogenes infection.36,37 These findings are also consistent with previously published observations in a model of arthritis induced by bacterial cell wall fragments from S. pyogenes.38 In this arthritis model, mice deficient in MyD88 expression showed significantly reduced inflammatory cytokines levels than wild-type littermates and failed to develop joint inflammation after induction of streptococcal cell wall arthritis.38

The absence of MyD88 did not affect, however, the capacity of neutrophils and macrophages to ingest and kill S. pyogenes. This observation is consistent with recent reports in which the authors argued against a role of MyD88 signaling in phagocytosis and killing of pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes39 or Burkholderia pseudomallei.40

One interesting and unexpected finding that surfaced during the course of these studies was the fact that, despite the lack of inflammatory mediators, histopathological examination of the organs of S. pyogenes-infected MyD88−/− mice evidenced a high amount of infiltrating inflammatory cells. A closer examination of these recruited cells revealed that they were eosinophils. This observation was very surprising since the primary role of eosinophils is considered to be defense against helminth infection.41 The eosinophil biology is ideally adapted for this host defense role, and any inflammatory participation in other diseases may be considered an aberration of this primary defense mechanism. Thus, inappropriate accumulation and activation of eosinophils can result in the release of a range of inflammatory mediators, including toxic granule proteins, cytokines, and activated oxygen species, which might contribute to disease pathogenesis by inducing tissue damage.42

An intriguing issue in our study was the mechanism of eosinophil recruitment in the organs of MyD88−/− mice during S. pyogenes infection. A number of Th2-type cytokines (eg, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13),43,44,45 adhesion molecules,46 and chemokines such as the eotaxins27 have been shown to be involved in the trafficking of eosinophils into inflammatory sites. Of the cytokines implicated in modulating leukocyte recruitment, only IL-5 and the eotaxins selectively regulate eosinophil trafficking.47 However, levels of eotaxins and IL-5 were not detectable in the serum and organs of S. pyogenes-infected MyD88−/− mice.

An additional mechanism reported to regulate the transmigration of eosinophils is based in the production of naturally occurring chemokine antagonists. While most authors have focused on the positive effect of chemokines on cells, recent attention has been drawn to the inhibitory activities of chemokines on various target cells.28,29,30,31,32 Among these regulatory chemokines, MIG/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 have been shown to block eosinophil chemoattraction and function in vitro and in vivo.28,29,30,31,32 As the levels of MIG/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 were significantly increased in the serum of C57BL/6 mice on S. pyogenes infection and totally absent in the serum of infected MyD88−/− mice, it is possible to conclude that the production of MIG/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 is controlled by signaling through MyD88 and that the absence of these inhibitory chemokines in MyD88−/− mice may facilitate the transmigration of eosinophils into the infected tissue. Further experiments are underway to validate this hypothesis.

Interestingly, both MIG/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 can be detected in high amounts in tonsil fluid from patients with streptococcal pharyngitis, and they have been shown to exhibit in vitro anti-microbial activity against S. pyogenes.48 Therefore, the lack of these antimicrobial chemokines in MyD88−/− mice may also directly contribute to the uncontrolled growth of S. pyogenes observed in these animals.

In summary, our results indicate that the ultimate distribution and function of inflammatory cells during S. pyogenes infection is controlled by MyD88 signaling pathway. Thus, MyD88 is required for the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as KC and MCP-1 to focus effector cells (neutrophils and macrophages) to the local site of infection to contain the infection. However, MyD88 signaling is also needed for the production of regulatory chemokines such as MIG/CXCL9 and IP-10 to inhibit the recruitment of unwanted inflammatory cells with potential detrimental effects (eg, eosinophils). Our results support a new paradigm concerning the role of MyD88 signaling in skewing the inflammatory response toward the most effective effector-functions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Angelika Höhne, Sabine Lehne, Claudia Höltje, and Anna Link for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Eva Medina, Dr. Infection Immunology Research Group, Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research, Inhoffenstraße 7, D-38124 Braunschweig, Germany. E-mail: eva.medina@helmholtz-hzi.de.

Supported by internal funding of the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research.

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

Current address of T.G.L.: Department of Clinical Sciences, Biomedical Center, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

References

- Jaggi P, Shulman ST. Group A streptococcal infections. Pediatr Rev. 2006;27:99–105. doi: 10.1542/pir.27-3-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R, Janeway C., Jr The Toll receptor family and microbial recognition. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:452–456. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01845-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi F, Smith KD, Ozinsky A, Hawn TR, Yi EC, Goodlett DR, Eng JK, Akira S, Underhill DM, Aderem A. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature. 2001;410:1099–1103. doi: 10.1038/35074106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Kaisho T, Sato S, Sanjo H, Matsumoto M, Hoshino K, Wagner H, Takeda K, Akira S. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–745. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Takada H, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Differential roles of TLR2 and TLR4 in recognition of gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial cell wall components. Immunity. 1999;11:443–451. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signaling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Kopp E, Stadlen A, Chen C, Ghosh S, Janeway CA., Jr MyD88 is an adaptor protein in the hToll/IL-1 receptor family signaling pathways. Mol Cell. 1998;2:253–258. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi O, Kawai T, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Tsutsui H, Sakagami M, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity. 1998;9:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Akira S. Cutting edge: tLR2-deficient and MyD88-deficient mice are highly susceptible to Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Immunol. 2000;165:5392–5396. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albiger B, Sandgren A, Katsuragi H, Meyer-Hoffert U, Beiter K, Wartha F, Hornef M, Normark S, Normark BH. Myeloid differentiation factor 88-dependent signaling controls bacterial growth during colonization and systemic pneumococcal disease in mice. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1603–1615. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leendertse M, Willems RJ, Giebelen IA, van der Pamgaart PS, Wiersinga WJ, de Vos AF, Florquin S, Bonten MJ, van der Poll T. TLR2-dependent MyD88 signaling contributes to early host defense in murine Enterococcus faecium peritonitis. J Immunol. 2008;180:4865–4874. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerrett SJ, Liggitt HD, Hajjar AM, Wilson CB. Cutting edge: myeloid differentiation factor 88 is essential for pulmonary host defense against Pseudomonas aeruginosa but not Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol. 2004;172:3377–3381. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard C, Puel A, Bonnet M, Ku CL, Bustamante J, Yang K, Soudais C, Dupuis S, Feinberg J, Fieschi C, Elbim C, Hitchcock R, Lammas D, Davies G, Al-Ghonaium A, Al-Raynes H, Al-Jumaah S, Al-Hajjar S, Al-Mohsen IZ, Frayha HH, Rucker R, Hawn TR, Aderem A, Tufenkeji H, Haraguchi S, Day NK, Good RA, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Ozinsky A, Casanova JL. Pyogenic bacterial infections in humans with IRAK-4 deficiency. Science. 2003;299:2076–2079. doi: 10.1126/science.1081902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bernuth H, Picard C, Jin Z, Pankla R, Xiao H, Ku CL, Chrabieh M, Mustapha IB, Ghandil P, Camcioglu Y, Vasconcelos J, Sirvent N, Guedes M, Vitor AB, Herrero-Mata MJ, Arostegui JI, Rodrigo L, Alsina L, Ruiz-Ortiz E, Juan M, Fortuny C, Yagüe J, Anton J, Pascal M, Chang HH, Janniere L, Rose Y, Garty BZ, Chapel H, Issekutz A, Marodi L, Rodriguez-Gallegoi C, Banchereau J, Abel L, Li X, Chaussabel D, Puel A, Casanova JL. Pyogenic bacterial infections in humans with MyD88 deficiency. Science. 2008;321:691–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1158298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku CL, von Bernuth H, Picard C, Zhang SY, Chang HH, Yang K, Chrabieh M, Issekutz AC, Cunningham CK, Gallin J, Holland SM, Roifman C, Ehl S, Smart J, Tang M, Barrat FJ, Levy O, McDonald D, Day-Good NK, Miller R, Takada H, Hara T, Al-Hajjar S, Al-Ghonaium A, Speert D, Sanlaville D, Li X, Geissmann F, Vivier E, Marodi L, Garty BZ, Chapel H, Rodriguez-Gallego C, Bossuyt X, Abel L, Puel A, Casanova JL. Selective predisposition to bacterial infections in IRAK-4-deficient children: IRAK-4-dependent TLRs are otherwise redundant in protective immunity. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2407–2422. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity. 1999;11:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weighardt H, Kaiser-Moore S, Vabulas RM, Kirschning CJ, Wagner H, Holzmann B. Cutting edge: myeloid differentiation factor 88 deficiency improves resistance against sepsis caused by polymicrobial infection. J Immunol. 2002;169:2823–2827. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso G, Midiri A, Beninati C, Biondo C, Galbo R, Akira S, Henneke P, Golenbock D, Teti G. Dual role of TLR2 and myeloid differentiation factor 88 in a mouse model of invasive group B streptococcal disease. J Immunol. 2004;172:6324–6329. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loof TG, Goldmann O, Medina E. Immune recognition of Streptococcus pyogenes by dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2785–2792. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01680-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz N, Siller M, Schaljo B, Pirzada ZA, Gattermeier I, Vojtek I, Kirschning CJ, Wagner H, Akira S, Charpentier E, Kovarik P. Group A streptococcus activates type I interferon production and MyD88-dependent signaling without involvement of TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19879–19887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802848200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loof TG, Rohde M, Chhatwal GS, Jung S, Medina E. The contribution of dendritic cells to host defenses against Streptococcus pyogenes. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1794–1803. doi: 10.1086/523647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method for estimating fifty percent end points. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Goldmann O, Sastalla I, Wos-Oxley M, Rohde M, Medina E. Streptococcus pyogenes induces oncosis in macrophages through the activation of an inflammatory programmed cell death pathway. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:138–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya N, Vyas DK, Fechner FP, Gliklich RE, Metson R. Tissue eosinophilia in chronic sinusitis: quantification techniques. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:1102–1105. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strath M, Warren DJ, Sanderson CJ. Detection of eosinophils using an eosinophil peroxidase assay: its use as an assay for eosinophil differentiation factors. J Immunol Methods. 1985;83:209–215. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(85)90242-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel R, Beck LA, Stellato C, Schleimer RP. Chemokines and allergic disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:723–742. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson PC, Zimmermann N, Brandt EB, Muntel EE, Doepker MP, Kavanaugh JL, Mishra A, Witte DP, Zhang H, Farber JM, Yang M, Foster PS, Rothenberg ME. Negative regulation of eosinophil recruitment to the lung by the chemokine monokine induced by IFN-gamma (Mig, CXCL9). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1987–1992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308544100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson PC, Zhu H, Williams DA, Zimmermann N, Rothenberg ME. CXCL9 inhibits eosinophil responses by a CCR3- and Rac2-dependent mechanism. Blood. 2005;106:436–443. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loetscher P, Pellegrino A, Gong JH, Mattioli I, Loetscher M, Bardi G, Baggiolini M, Clark-Lewis I. The ligands of CXC chemokine receptor 3. I-TAC, Mig, and IP10, are natural antagonists for CCR3. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2986–2991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthou G, Duchesnes CE, Williams TJ, Pease JE. CCR3 functional responses are regulated by both CXCR3 and its ligands CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2241–2250. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MS, Kunkel SL, Lukacs NW. Regulation of cockroach antigen-induced allergic airway hyperreactivity by the CXCR3 ligand CXCL9. J Immunol. 2004;173:615–623. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber JM. A macrophage mRNA selectively induced by gamma-interferon encodes a member of the platelet factor 4 family of cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5238–5242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao H, Kohanawa M. Endogenous interleukin-6 plays a crucial protective role in streptococcal toxic shock syndrome via suppression of tumor necrosis factor alpha production. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3745–3748. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3745-3748.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DW, Raeder R, Van Cleave VH, Boyle MD. Protection of mice from group A streptococcal skin infection by interleukin-12. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1643–1645. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldmann O, Rohde M, Chhatwal GS, Medina E. Role of macrophages in host resistance to group A streptococci. Infect Immun. 2004;72:2956–2963. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2956-2963.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarini AA, Lang KS, Verschoor A, Recher M, Zinkernagel AS, Nizet V, Odermatt B, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Innate immune-induced depletion of bone marrow neutrophils aggravates systemic bacterial infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7107–7112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901162106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joosten LA, Koenders MI, Smeets RL, Heuvelmans-Jacobs M, Helsen MM, Takeda K, Akira S, Lubberts E, van de Loo FA, van den Berg WB. Toll-like receptor 2 pathway drives streptococcal cell wall-induced joint inflammation: critical role of myeloid differentiation factor 88. J Immunol. 2003;171:6145–6153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelson BT, Unanue ER. MyD88-dependent but Toll-like receptor 2-independent innate immunity to Listeria: no role for either in macrophage listericidal activity. J Immunol. 2002;169:3869–3875. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersinga WJ, Wieland CW, Roelofs JJ, van der Poll T. MyD88 dependent signaling contributes to protective host defense against Burkholderia pseudomallei. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klion AD, Nutman TB. The role of eosinophils in host defense against helminth parasites. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariyawasam HH, Robinson DS. The eosinophil: the cell and its weapons, the cytokines, its locations. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;27:117–127. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-939514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher A, Coffman RL, Hieny S, Cheever AW. Ablation of eosinophil and IgE responses with anti-IL-5 or anti-IL-4 antibodies fails to affect immunity against Schistosoma mansoni in the mouse. J Immunol. 1990;145:3911–3916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser R, Fehr J, Bruijnzeel PL. IL-4 controls the selective endothelium-driven transmigration of eosinophils from allergic individuals. J Immunol. 1992;149:1432–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie S, Okubo Y, Hossain M, Sato E, Nomura H, Koyama S, Suzuki J, Isobe M, Sekiguchi M. Interleukin-13 but not interleukin-4 prolongs eosinophil survival and induces eosinophil chemotaxis. Intern Med. 1997;36:179–185. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.36.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochner BS, Schleimer RP. The role of adhesion molecules in human eosinophil and basophil recruitment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1994;94:427–438. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(94)90195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin SM, Conroy DM, Williams TJ. Eotaxin and eosinophil recruitment: implications for human disease. Mol Med Today. 2000;6:20–27. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(99)01635-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egesten A, Eliasson M, Johansson HM, Olin AI, Mörgelin M, Mueller A, Pease JE, Frick IM, Björk L. The CXC chemokine MIG/CXCL9 is important in innate immunity against Streptococcus pyogenes. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:684–693. doi: 10.1086/510857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]