Abstract

Background

Tobacco smoking has been found to increase after the experience of a traumatic event and has been associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Initiation and persistence of cigarette smoking is moderately heritable; two recent investigations have implicated the COMT Val158Met (also known as rs4680) polymorphism in smoking age of initiation, dependence, as well as in quantity and frequency of smoking.

Method

To examine a possible association of COMT Val158Met and posttrauma increases in cigarette smoking, we studied 614 adults from the 2004 Florida Hurricane Study who returned saliva DNA samples via mail.

Results

PTSD was strongly associated with increased smoking. Moreover, each COMT Val158Met ‘Met’ allele predicted a 2.10 fold risk of smoking post-hurricane independent of PTSD; follow-up analyses revealed that this finding was primarily driven by European-American males.

Conclusions

This study represents the first genetic association study (to our knowledge) of smoking behavior following an acute stressor.

Keywords: cigarette smoking, trauma, COMT, gene association, disaster, posttraumatic stress disorder

Stress has long been recognized as a potential risk factor for smoking (Kassel, Stroud, & Paronis, 2003). Numerous studies have shown that exposure to a potentially traumatic event (PTE) is associated with increased likelihood and frequency of smoking (Joseph, 1993; Parslow, 2006; Vlahov et al., 2002). As observed by Vlahov et al. (2002; 2004), psychological symptoms (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) in the aftermath of traumatic event exposure may also be related to smoking. Another large general population sample found that PTE exposure increased risk of nicotine dependence and, moreover, reported that PTSD was associated with higher risk of dependence than PTE exposure alone (Hapke et al., 2005). In a sample of men who formerly belonged to a civilian resistance against the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, those with PTSD smoked a greater number of cigarettes each day than did those without PTSD (Op Den Velde et al., 2002). In short, being exposed to a PTE, as well as having a PTSD has been shown to confer greater risk for cigarette smoking and for increases in smoking behaviors. Although these stress-related variables have been found to be predictive of smoking behavior in the aftermath of a PTE, there is a large amount of variance that remains unexplained, implicating the need to include other variables, such as genetic variants.

Genetic factors have been found to increase risk of smoking; heritability of smoking initiation is estimated to range from 30–80% and smoking persistence and dependence found to range from 50–70% (Munafo, 2008). Progress has also been made in identifying specific chromosomal regions and genetic variants associated with increased risk of smoking. Four recent gene-association studies have implicated the COMT Val158Met polymorphism (also known as rs4680) in smoking age of initiation, dependence, and severity (Beuten, Payne, Ma, & Li, 2006; Enoch, Waheed, Harris, Albaugh, & Goldman, 2006; Guo et al., 2007; Tochigi et al., 2007). However, no study of which we are aware has examined the role of specific genetic variants in risk of increased smoking following PTE exposure. This paper examines whether the COMT Val158Met polymorphism predicts increased smoking among participants in 2004 Florida Hurricane Study (Acierno, Ruggiero, Kilpatrick, Resnick, & Galea, 2006).

Investigations aimed at identification of specific genes associated with smoking, have frequently focused on functional genes known to influence the dopaminergic system. Dopamine reward pathways have been repeatedly implicated in nicotine release and dependence. The COMT Val158Met is of particular interest in this regard. It involves a common valine (val; high activity) to methionine (met; low activity) transition that has been associated with a 3–4 fold difference in homozygous COMT enzyme activity, with heterozygotes showing intermediary enzyme activity (Lotta, 2005; Weinshilboum, 1999). The COMT enzyme catalyzes the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosyl-methionine to a hydroxyl group of catecholamines (e.g., dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine; Weinshilboum, 1999). Thus, the COMT Val158Met polymorphism may act on the dopaminergic reward pathways implicated in smoking through its influence on COMT enzyme activity.

The Val/Val genotype was associated with higher risk of heavy smoking in male participants, but not female participants, in a sample of 451 healthy Japanese volunteers (Tochigi et al., 2007). In contrast, increased Val allele frequency was found in female, but not male, smokers compared with nonsmokers in a sample of 342 American Plains Indians (Enoch et al., 2006). One explanation for these differences may be related to ethnicity, as both sex-dependent as well as ethnicity-dependent effects were reported in an investigation of 602 African-American (AA) and European-American (EA) families, with the Val allele generally found to be protective (Beuten et al., 2006). Inconsistencies may also be explained by differences in smoking-related outcome variables (e.g., amount of smoking, endorsement of any current smoking, persistence of smoking). For example, although COMT Val158Met was not associated with smoking initiation, persistence, or cessation in a sample of Chinese males, current smokers with the Met allele were more likely to show nicotine dependence and had started smoking at earlier ages (Guo et al., 2007). Two other investigations reported no association between COMT Val158Met and smoking behaviors (David, 2002; McKinney, 2000). Inconsistent findings may be due to methodological and ascertainment differences across investigations, including important demographic differences (particularly racial composition and single sex investigations) and differences in smoking behaviors assessed (e.g., smoking persistence, amount). Further, published investigations have not assessed participant exposure to PTEs.

Smoking behaviors, particularly changes in behavior, following a PTE are likely highly to be influenced by an individual’s overall response to the event. The COMT Val158Met genotype has previously been associated with higher sensory and affective ratings in response to sustained pain (Zubieta et al., 2003), sensitivity to negative internal affective states (Zubieta et al., 2003), and fMRI reactivity (in the limbic system, select prefrontal areas, and the visuospatial attentional system) to unpleasant stimuli (Smolka et al., 2005). COMT variation is also associated to trait anxiety (Stein et al, 2005). Individuals with the Met allele may be more sensitive to environmental stressors and may respond to mild or moderate levels of stress with increased emotional dysregulation.

Among the four published studies of COMT Val158Met in nicotine dependence-related traits reporting an association, the findings are mixed as to which allele is protective, with two studies reporting Val is protective, and two studies reporting that Met is protective. Published investigations of smoking and COMT Val158Met have shown notable inconsistencies methodology, including sample population and dependent variables of smoking. To date, no study has examined smoking behaviors in response to PTEs. The present study examined PTSD and COMT in relation to post-disaster increased smoking. Given findings from investigations of sensitivity to unpleasant stimuli, as well the largest and most representative study to date (Beuten et al., 2006) finding that the Met allele being associated with nicotine dependence, we hypothesized that the low activity variant (Met allele) of the COMT Val158Met polymorphism would be associated with increased smoking after one or more hurricanes during the 2004 Florida Hurricane season. Further, given previous findings of relationships among PTSD and smoking behavior (Hapke et al., 2005), we hypothesized that PTSD would be predictive of increased smoking.

Methods

Data Collection and Sample

Data from 614 participants in the 2004 Florida Hurricane Study who completed structured telephone interviews and provided saliva samples through the mail that yielded genotype data for COMT Val158Met (also known as rs4680) are the focus of the current study. Detailed methodology about the Florida Hurricane Study are provided elsewhere (Acierno et al., 2006).

Demographic characteristics of the 614 participants were as follows: 35.8% men, 64.2% women; 22.1% ≤ 59 years of age, 77.0% ≥ 60 years of age; 90.8% white, 3.7% black, 3.7% Hispanic, 1.6% other, 0.5% missing self-report race/ethnicity data. Consent was obtained verbally from the participants, and a letter documenting the elements of verbal consent and providing them with contact information for the principal investigator was mailed. Participants were compensated $20 for a completed diagnostic interview and returned saliva sample. All relevant institutions’ review boards approved all procedures.

Assessment Procedure

Interviews were conducted via telephone with a probability sample of English-and Spanish-speaking adults from telephone households in 33 counties in Florida within 6–9 months of the 2004 Florida hurricane season, between April 5 and June 12, 2005. Oversampling of older adults (ages 60 and older) was conducted to address research questions specific to this age group. Sample selection and telephone interviewing was performed by Schulman, Ronca, Bucuvalas, Inc., a national survey research firm with expertise in conducting structured telephone interviews. By use of random-digit-dial procedures, households within the sampling frame were located. The most recent birthday method was used for selection of participants when multiple eligible adults were present within a household. Highly structured interview assessments were conducted via computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) format. Average length of the interviews was 26.5 minutes.

Increased smoking since the hurricanes was measured by asking participants, “Since the 2004 hurricanes: Have you been smoking more cigarettes than before the hurricanes?”

Hurricane exposure and social support were found to be associated with increased smoking in this sample and are included as covariates in logistic regression models. Hurricane exposure was assessed via use of factors previously identified in research on Hurricanes Hugo and Andrew (Freedy, Saladin, Kilpatrick, Resnick, & Saunders, 1994) on the basis of their relation to posthurricane psychiatric and health functioning: 1) presence during the storm (hurricane-force winds or major flooding); 2) lack of adequate access to food, water, electricity, telephone, or clothing for a week or longer; 3) at least two hurricane-related losses of furniture, sentimental possessions, automobile, pets, crops, trees, or garden; 4) displacement from home for 1 week or longer; and 5) non-reimbursed losses of at least $1,000. Based on previous research (Kilpatrick et al., 2007), high hurricane exposure was operationalized as having experienced two or more of these five indicators; 45.8% of the participants had high hurricane exposure.

We measured pre-hurricane perceived social support by using a slightly altered five-item version of the Medical Outcomes Study module (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991) (sample range=0–20; mean=15.9, SD=4.8). We defined low social support as a score of 15 or less (36.9% of the sample) based on the cutoff score derived from prior work (Acierno et al., 2006). This scale had good reliability (alpha=0.86).

PTSD since the hurricanes was assessed with the National Women’s Study (NWS) PTSD module, a widely used measure in population-based epidemiological research originally modified from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Research on the NWS PTSD module has provided support for concurrent validity and several forms of reliability (e.g., temporal stability, internal consistency, diagnostic reliability) (Resnick, Kilpatrick, Dansky, Saunders, & Best, 1993). The NWS PTSD module was validated in the DSM-IV PTSD field trial against the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID), in which the interrater kappa coefficient was 0.85 for the diagnosis of PTSD and comparisons between scores on the NWS PTSD module and the SCID yielded a kappa coefficient of 0.71 for current PTSD (Kilpatrick et al., 1998). Research also has found high correspondence between telephone versus in-person administration of the PTSD module. We operationalized PTSD diagnosis based on DSM-IV symptom requirements, including functional impairment.

Collection of DNA samples

As described elsewhere (Kilpatrick et al., 2007), saliva samples were obtained by use of a mouthwash protocol, and were sent via mail to the Yale University laboratory for DNA extraction and analyses. Saliva samples were returned by 651 participants (42.2% response rate), and of this subsample, valid genetic ancestry data were available for 623 cases (95.7%), and valid COMT Val158Met genotype data were available for 614 cases (94.3%). Returners versus non-returners of saliva samples did not differ in relation to key study variables (i.e., sex, level of hurricane exposure, level of social support, increased smoking status). Additional methodological details on response rate and associations of participation are reported elsewhere (Galea et al., 2006).

Genotyping

Extraction of DNA from saliva samples was conducted via use of PUREGENE (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis) kits. Genotyping of SNPs was conducted with a fluorogenic 5′ nuclease assay method (“TaqMan”) using the ABI PRISM 7900 Sequence Detection System (ABI, Foster City, CA, USA). All SNPs were assayed in duplicate; discordant genotypes were discarded. In addition, 36 markers were assayed, yielding ancestry information (Yang, Zhao, Kranzler, & Gelernter, 2005). We added one additional SNP marker, SLC24A5 (Lamason et al., 2005) to the ancestry panel.

Ancestry Proportion Scores

Spurious associations can result from variation in allele frequency and prevalence of trait by population. To control for this, ancestry proportion scores were generated. Bayesian cluster analysis was used to estimate participants’ ancestries by with the marker panel described above and STRUCTURE software (Pritchard & Rosenberg, 1999). For the STRUCTURE analysis, we specified the “admixture” and “allele frequencies correlated” models and used 100,000 burn-in and 100,000 Markov chain Monte Carlo iterations.

Statistical Analyses

Chi-squared analyses were utilized to test whether PTSD and rs4680 were associated with increased smoking post-hurricane. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine whether any observed association persisted after adjusting for sex, age, ancestral proportion scores, social support, and hurricane exposure. Given previous reports of sex and racial/ethnic differences in the COMT Val158Met polymorphism, we conducted exploratory analyses stratified by sex and race/ethnicity.

Results

Post-hurricane Increased Smoking and COMT Val158Met Genotype

Increased smoking post-hurricane was reported by 4.4% of participants (n=27). Allele frequencies were consistent with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium expectations. Genotype frequencies were similar to those reported elsewhere (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/snp_ref.cgi?rs=4680). For EA participants: Val/Val (n=117, 21.1%), Val/Met (n=282, 50.8%, Met/Met (n=156, 28.1%); for African American participants: Val/Val (n=11, 47.8%), Val/Met (n=10, 43.5%, Met/Met (n=2, 8.7%);. and for all other participants: Val/Val (n=7, 21.2%), Val/Met (n=18, 54.5%, Met/Met (n=8, 24.2%). Self-reported race/ethnicity was not associated with genotype frequency (χ2[1, n=611]=1.93, p=.44) but was associated with increased smoking (χ2[1, n=611]=7.61, p<.01) with EAs more likely to report increased smoking. Thus ancestry coefficients were included in our logistic regression models to insure that population stratification was not a potential cause of false positive findings.

Prediction of Increased Smoking: Full Sample

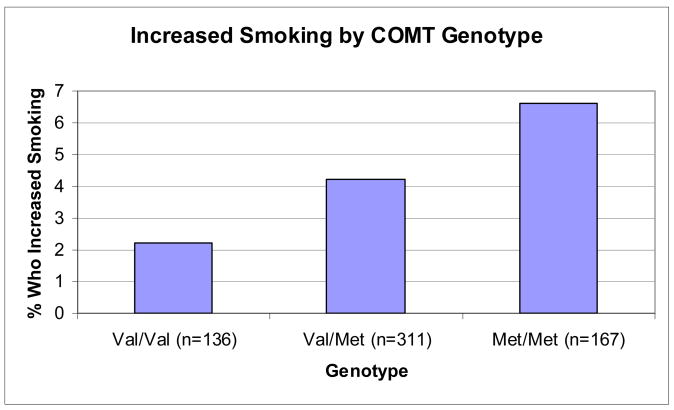

The chi-square test between post-hurricane PTSD and increased smoking as significant (χ2=49.09, df=1, n=614 p<.001), with individuals with PTSD being more likely to report increased smoking than those without PTSD. The chi-squared linear-by-linear association test supported a trend for an association between COMT Val158Met and post-hurricane increased smoking (χ2=3.47, df=1, n=614 p=0.06). The association between COMT Val158Met genotype and post-hurricane increased smoking is shown in Figure 1. The final results of the logistic regression analyses for the full sample are shown in Table 1. PTSD was highly predictive of increased smoking (OR=14.23). COMT Val158Met was also predictive of increased smoking, with each Met allele confering 2.10 times increased risk of increased smoking post-hurricane in the fully-adjusted model.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Participants by COMT Val158Met Genotype Who Reported Increased Smoking Post-hurricane (p=.06).

Table 1.

Final Logistic Regression Analysis of the Association between COMT Val158Met Genotype and Increased Smoking Post-hurricane in the Full Sample.

| Increased smoking |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p |

| Female Sex | 1.12 | .45 – 2.82 | .81 |

| Age greater than 60 years | 4.24 | 1.74 – 10.34 | <.001 |

| Ancestral proportion score | .83 | .12 – 5.78 | .85 |

| High hurricane exposure | 1.05 | .42 – 2.58 | .92 |

| Low social support | 3.87 | 1.52 – 9.81 | <.001 |

| PTSD since the hurricane | 14.23 | 4.34 – 46.67 | <.001 |

| COMT Val158Met (Met is risk allele) | 2.10 | 1.11 – 3.98 | <.05 |

Stratified Analyses of Increased Smoking and COMT Val158Met Genotype

When we stratified by sex and population, we found that the COMT Val158Met genotype was associated in a linear-by-linear analysis with increased smoking in EA men (χ2[1, n=199]=5.62, p<.05), and no other subgroups. This finding in was in a consistent direction as was found in the full sample, with the Met allele associated with increased smoking. As the finding in the full sample appeared to be mostly driven by EA males, this subgroup was selected and a logistic regression predicting increased smoking, controlling for age, social support, and hurricane exposure, was conducted. PTSD was not included in this analysis as it was not prevalent in males. This analysis revealed that the only significant predictor of increased smoking was the COMT Val158Met genotype (OR=4.94; 95% CI: 1.03–23.79), again suggesting that the low activity variant, Met, was associated with risk of increased smoking.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present investigation is the first genetic association study of smoking to examine genotype-phenotype relations within a sample exposed to an acute stressor. We found that both PTSD and COMT Val158Met were significant predictors of increased smoking post-hurricane, even after controlling for other key variables (age, ancestry, social support, gender). The low activity variant of the COMT Val158Met polymorphism was associated with post-hurricane increased smoking. This finding suggests that, for individuals with the Met allele, exposure to even low levels of environmental stress are sufficient to increase smoking behaviors above and beyond the variance accounted for by PTSD, a replicated predictor of smoking (Vlahov et al., 2002). PTSD was the most powerful predictor of increased smoking in our study, with individuals meeting criteria at over 14 times higher risk for increased smoking than individuals without the disorder.

Of note, our genetic association findings were generally driven by EA males in the sample, as demonstrated by our stratified analyses. Prior examinations have also noted sex differences in associations between COMT and smoking behaviors (Beuten et al., 2006; Tochigi, et al., 2007). COMT expression is regulated in part by estrogen (Jiang, Xie, Ramsden, & Ho, 2003; Xie, Ho, & Ramsden, 1999) and women have been reported to show 20–30% lower COMT activity than men (Boudikova, Szumlanski, Maidak, & Weinshilboum, 1990). Further, sex differences have been identified in the associations between COMT and brain anatomy (Zinkstok et al., 2006). One recent meta-analysis reported sex differences in genetic influences on smoking, such that genetic influences on smoking initiation were stronger in females than males and genetic influences on smoking persistence were stronger in males than females (Li, Cheng, Ma, & Swan, 2003). Further, sex mediated the effects of shared environment on smoking behavior, such that the effects of shared environment on both smoking initiation and persistence were 2 to 2.5-fold greater in males relative to females.

In addition to the replicated finding of PTSD being predictive of smoking, and the novel finding of the COMT genotype being predictive of increased smoking post-disaster, it is also notable that low social support was predictive of increased smoking. Under conditions of low social support and high hurricane exposure, those with the risk a genotype (s/s) of the 5-HTTLPR were at increased risk for PTSD in this sample (Kilpatrick et al., 2007). Given that low social support and PTSD were risk factors for increased smoking in the present study, possible interrelationships between these variables may be important to fully understand smoking risk in stress-exposed samples. Notably, as social support is also related to PTSD risk, it is possible that increasing social support may have direct effects on PTSD and health risk behaviors (such as smoking). Our social support finding has public health implications, as instrumental assistance (e.g., food, shelter), emotional support, and simple companionship delivered via churches, synagogues, mosques, senior centers, schools, and other public or semi-public institutions may well be among the best and most efficient approaches to community-based intervention following natural disasters such as hurricanes for the great majority of affected individuals who may have low social support. Our finding of PTSD being predictive of increased smoking is not surprising, and suggests that effective treatment of this disorder may also have the additional benefit of simultaneously decreasing an important health-risk behavior.

An important strength of the present methodology is population-based sampling of individuals exposed to a natural disaster, which affords some control for the gene-environment correlation (the propensity of genetic factors to influence exposure to environmental conditions) that limits many genetic investigations. However, change in smoking behavior was assessed using a single item, collected 6–9 months following hurricane exposure, introducing the potential for recall bias. Further, due to the relatively low prevalence of participants who reported increased smoking post-hurricane in this sample, we had limited power to examine to examine the role of other potentially important variables. Additional research is needed to replicate and extend our findings. However, our results suggest that studying a recently disaster-exposed sample is both feasible and may improve power to find gene-phenotype associations.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH grant MH05220, NIMH and NIN research grant MH07055, and NIDA grants K24 DA15105, R01 DA12690, and R01 DA12849. Dr. Amstadter is supported by NIMH grant 18869. Dr. Koenen is supported by NIMH grants K08-MH070627 and MH078928.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicting financial or other competing interests.

Contributor Information

Ananda B. Amstadter, Email: amstadt@musc.edu.

Nicole R. Nugent, Email: Nicole_Nugent@brown.edu.

Karestan C. Koenen, Email: kkoenen@hsph.harvard.edu.

Kenneth J. Ruggiero, Email: ruggierk@musc.edu.

Ron Acierno, Email: acierno@musc.edu.

Sandro Galea, Email: sgalea@umich.edu.

Dean G. Kilpatrick, Email: kilpatdg@musc.edu.

Joel Gelernter, Email: joel.gelernter@yale.edu.

References

- Acierno R, Ruggiero KJ, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Galea S. Risk and protective factors for psychopathology among older versus younger adults after the 2004 Florida hurricanes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(12):1051–1059. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221327.97904.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuten J, Payne TJ, Ma JZ, Li MD. Significant association of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) haplotypes with nicotine dependence in male and female smokers of two ethnic populations. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(3):675–684. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudikova B, Szumlanski C, Maidak B, Weinshilboum R. Human liver catechol-O-methyltransferase pharmacogenetics. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1990;48(4):381–389. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1990.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David S, Johnstone E, Griffiths SE, Murphy M, Yudkin P, Mant D, et al. No association between functional catechol-O-methyltransferase 1947A4G polymorphism and smoking initiation, persistent smoking or smoking cessation. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12:256–268. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200204000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch M, Waheed JF, Harris CR, Albaugh B, Goldman D. Sex differences in the influence of COMT Val158Met on alcoholism and smoking in plains American Indians. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:399–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedy JR, Saladin ME, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Saunders BE. Understanding acute psychological distress following natural disaster. J Trauma Stress. 1994;7(2):257–273. doi: 10.1007/BF02102947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Acierno R, Ruggiero K, Resnick H, Tracy M, Kilpatrick D. Social context and the psychobiology of posttraumatic stress. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1071:231–241. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo SC, DaFang, Zhou Dong Feng, Sun Hong Qiang, Wu Gui Ying, Haile Colin N, Kosten Therese A, Kosten Thomas R, Zhang Xiang Yang. Association of functional catechol O-methyl transferase (COMT) Val108Met polymorphism with smoking severity and age of smoking initiation in Chinese male smokers. Psychopharmacology. 2007;190:449–456. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0628-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hapke U, Schumann A, Rumpf H, Ulrich J, Konerding U, Meyer C. Association of smoking and nicotine dependence with trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a general population sample. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2005;193:843–846. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000188964.83476.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Xie T, Ramsden DB, Ho SL. Human catechol-O-methyltransferase down-regulation by estradiol. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45(7):1011–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S, Yule W, Williams R, Hodgkinson P. Increased substance use in survivors of the Herald of Free Enterprise disaster. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1993;66:185–191. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1993.tb01740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Stroud LR, Paronis CA. Smoking, stress, and negative affect: Correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:270–304. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Koenen KC, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Galea S, Resnick HS, et al. The serotonin transporter genotype and social support and moderation of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in hurricane-exposed adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1693–1699. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Freedy JR, Pelcovitz D, Resick PA, Roth S, et al. The posttraumatic stress disorder field trial: evaluation of the PTSD construct—criteria A through E. In: Widiger T, Pincus HA, First MB, Ross R, Davis W, editors. DSM-IV Sourcebook. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1998. pp. 803–844. [Google Scholar]

- Lamason RL, Mohideen MA, Mest JR, Wong AC, Norton HL, Aros MC, et al. SLC24A5, a putative cation exchanger, affects pigmentation in zebrafish and humans. Science. 2005;310(5755):1782–1786. doi: 10.1126/science.1116238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MD, Cheng R, Ma JZ, Swan GE. A meta-analysis of estimated genetic and environmental effects on smoking behavior in male and female adult twins. Addiction. 2003;98(1):23–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotta T, Vidgren J, Tilgmann C, Ulmanen I, Melen K, Julkunen I, et al. Kinetics of human soluble and membrane-bound catechol-O-methyltransferase a revised mechanism and dscription of the thermolabile variant of the enzyme. Biochemistry. 2005;34:4202–4210. doi: 10.1021/bi00013a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney E, Walton RT, Yudkin P, Fuller A, Haldar NA, Mant D, et al. Association between polymorphisms in dopamine metabolic enzymes and tobacco consumption in smokers. Pharmacogenetics. 2000;10:483–491. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200008000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafo MR, Johnstone EC. Genes and cigarette smoking. Addition. 2008:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Op Den Velde W, Aarts PG, Falger PR, Hovens JE, Van Duijn H, De Groen JH, et al. Alcohol use, cigarette consumption and chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2002;37:355–361. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.4.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parslow R, Jorm AF. Tobacco use after experiencing a major natural disaster: analysis of a longitudinal study of 2063 young adults. Addiction. 2006;101:1044–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard JK, Rosenberg NA. Use of unlinked genetic markers to detect population stratification in association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65(1):220–228. doi: 10.1086/302449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Dansky BS, Saunders BE, Best CL. Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:984–991. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS Social Support Survey. Social Science and Medicine. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolka MN, Schumann G, Wrase J, Grusser SM, Flor H, Mann K, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase val158met genotype affects processing of emotional stimuli in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2005;25(4):836–842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1792-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tochigi M, Suzuki K, Kato C, Otowa T, Hibino H, Umekage T, Kato N, Sasaki T. Association study of monoamine oxidase and catechol-O-methyltransferase genes with smoking behavior. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics. 2007;17:867–872. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282e9a51e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov D, Galea S, Resnick H, Ahern J, Boscarino JA, Bucuvales M, et al. Increased use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana amond Manhattan, New York residents after the September 11th terrorist attacks. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;155:988–996. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.11.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov, Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, Boscarino JA, Gold J, et al. Consumption of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana among New York City residents six months after the September 11 terrorist attacks. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30(2):385–407. doi: 10.1081/ada-120037384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshilboum R, Otterness DM, Szumlanski CL. Methylation pharmacogenetics: catechol-O-methyltransferase, thiopurine methyltransferase, and histamine N-methyltransferas. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1999;39:19–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie T, Ho SL, Ramsden D. Characterization and implications of estrogenic down-regulation of human catechol-O-methyltransferase gene transcription. Molecular Pharmacology. 1999;56(1):31–38. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang BZ, Zhao H, Kranzler HR, Gelernter J. Characterization of a Likelihood Based Method and Effects of Markers Informativeness in Evaluation of Admixture and Population Group Assignment. BMC Genet. 2005;6(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-6-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinkstok J, Schmitz N, van Amelsvoort T, de Win M, van den Brink W, Baas F, et al. The COMT val(158)met polymorphism and brain morphometry in healthy young adults. Neuroscience Letters. 2006;405(1–2):34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Heitzeg MM, Smith YR, Bueller JA, Xu K, Xu Y, et al. COMT val158met genotype affects mu-opioid neurotransmitter responses to a pain stressor. Science. 2003;299(5610):1240–1243. doi: 10.1126/science.1078546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]