Abstract

Understanding the trajectory of cognitive changes in the development of schizophrenia may shed light on the neurodevelopmental processes in the beginning stage of illness. Subjects at risk for psychosis (AR, n=48), patients in their first episode of schizophrenia (FE, n=20) and normal comparison subjects (NC, n=29) were assessed on a neurocognitive battery at baseline and at a 6-month follow-up. There were significant group differences across all cognitive domains as well as a significant group by time interaction in the verbal learning domain. After statistically controlling for practice effects and regression to the mean, a high proportion of FE subjects showed an improvement in verbal learning, while a significant number of AR subjects improved in general intelligence. Moreover, a higher than expected percentage of FE subjects, as well as AR subjects who later converted to psychosis, showed a deterioration in working memory and processing speed. These inconsistent trajectories suggest that some domains may improve with stabilization in the early stages of psychosis, while others may decline with progression of the illness, indicating possible targets for cognitive remediation strategies and candidate vulnerability markers for future psychosis.

Keywords: NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL, LONGITUDINAL, SCHIZOPHRENIA, AT RISK, PRODROMAL

The schizophrenia prodrome is a period of rapid developmental change that precedes illness onset and is characterized by a substantial functional decline together with the emergence of subthreshold psychotic symptoms (Yung & McGorry, 1996). Longitudinal studies have shown that the population who meets the “prodromal” definition, based on carefully defined criteria combining subsyndromal psychotic symptoms, family history and functional decline (Miller et al., 2003), has a 20 to 30% chance of converting to psychosis within one year of ascertainment (e.g., Cannon et al., 2008; Olsen and Rosenbaum, 2006; Yung et al., 2004).

The early identification of individuals in the prodromal phase and first episode of schizophrenia, using brain-based vulnerability markers, may add important insights into the neurodevelopmental processes and dynamic changes in this beginning stage of the illness. The present study is among the first to examine the magnitude and longitudinal course of neurocognitive dysfunction prior to and following the onset of psychosis. We will be using the term “at-risk” throughout this paper to refer to those individuals who are putatively “prodromal” for psychosis, as the latter state can only be truly diagnosed retrospectively. Neurocognitive vulnerability markers were selected because of established deficits across schizophrenia spectrum groups (Cadenhead et al., 1999; Cannon et al., 1994; Hawkins et al., 2004; Heinrichs & Zakanis, 1998), high reliability in repeated testing (Faraone et al., 1999; Heaton et al., 2001; Rund et al., 1997) and evidence of heritability (Ando et al., 2001; Greenwood et al., 2007; Posthuma et al., 2002). Unlike other endophenotypic markers which require special equipment and extensive training in order to be collected and analyzed, neurocognitive tests are relatively easy to administer in the office setting. Neurocognitive deficits may be important in understanding the pathogenesis of early psychosis, and could help to define individuals at greatest risk for the full-blown illness (Cadenhead, 2002). Moreover, assessing neurocognitive performance over time may reveal a decline in certain domains, which might indicate a greater risk for disability and a need for earlier and/or more aggressive treatment. Therefore, neurocognitive change over time could be another potential marker for vulnerability to disease that may shed light on both the pathological changes in brain structure/function that occur early in the illness, as well as abnormal variants of the normal brain changes that take place during adolescence and early adulthood.

Substantial cognitive deficits in people who go on to develop schizophrenia are apparent in childhood (Woodberry et al., 2008), tend to exacerbate before the onset of overt psychotic symptoms, and worsen even more with the initial episode of the illness (Bilder et al., 2006). However, widespread cognitive impairment should not be assumed in all people with schizophrenia, as cognitive heterogeneity is likely to be present at onset as well as throughout the illness. Joyce et al. (2005) found that although only half of their subjects with first-episode schizophrenia had a low premorbid IQ or a general cognitive decline from normal levels, all of them (including those with preserved high or average IQ) had a specific impairment in working memory. At a group level, however, it has been demonstrated that when compared to healthy normal comparison subjects, subjects at-risk for psychosis have neurocognitive deficits across multiple domains that are intermediate to those observed in first-episode schizophrenia patients (e.g., Eastvold et al., 2007; Keefe et al., 2006).

Longitudinal studies of first-episode schizophrenia groups have shown high stability of neurocognitive functioning over the first few years of the illness (e.g., Addington et al., 2005; Albus et al., 2006; Censits et al., 1997; Rund et al., 2007). There has been no evidence, in group data, of progressive cognitive deterioration after illness onset, as average performance either remained stable in most neurocognitive domains or improved slightly in some of them (e.g., Gold et al., 1999; Nopoulos et al., 1994; Sweeney et al., 1991). The relatively fewer studies that examined the change in neuropsychological function in at-risk subjects found that a greater cognitive impairment at baseline is associated with subsequent conversion (Keefe et al., 2006; Lencz et al., 2006). Moreover, a decline in verbal abilities (memory in particular) and intellectual functions might predict conversion to psychosis (Cosway et al., 2000; Brewer et al., 2005; Eastvold et al., 2007; Pukrop et al., 2007; Whyte et al., 2006). Interestingly, Niendam et al. (2007) found that a subset of their high risk subjects improved over an 8-month period on measures of speeded information processing, as well as visual and verbal learning/memory. However, the Niendam et al. (2007) study did not include a healthy comparison group to determine how much of the improvement observed was due to practice effects or decreased anxiety due to familiarity with the testing situation.

The primary aim of the current study was to examine and compare the stability and/or change in neurocognitive performance with repeated testing in the putative prodrome and first episode of schizophrenia. While there is substantial evidence to support the stability of illness-related deficits even up to 10 years after the acute onset period (Hoff et al., 2005), we do not know much about the evolution of those deficits in the early stages of psychosis. It is possible that some impaired functions are present before the onset of psychosis and remain stable throughout the prodrome and first episode of illness, while other abilities may decline with the onset of illness or may fluctuate with changes in clinical symptomatology and social functioning. Thus, our goal was to examine the pattern of change in neurocognitive performance over time at the group and individual levels. We hypothesized that the AR and FE groups would show significantly more changes in their performance over time relative to the NC group.

Method

Participants

Our samples consisted of 48 subjects at risk for psychosis (AR), 20 first-episode schizophrenia patients (FE) and 29 normal comparison subjects (NC), who were compared at baseline and 6-month follow-up on a battery of neurocognitive tests. The majority of the AR subjects (70.9%) met criteria for at least one of the two most common prodromal syndromes (Miller et al., 2003; Seeber & Cadenhead, 2005; Yung et al., 2005): “Attenuated Positive Symptom” (new onset of subsyndromal psychotic symptoms) and/or “Genetic Risk and Deterioration” (family history of schizophrenia in a first-degree relative or a diagnosis of schizotypal personality disorder that is associated with a recent decline in global functioning) per the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS; Miller et al., 2003) and established CARE (Cognitive Assessment and Risk Evaluation) criteria (Ballon et al., 2007). The Attenuated Positive Symptom (APS) category accounted for 28.2% of the at-risk sample, while 6.3% met criteria for the Genetic Risk and Deterioration (GRD) syndrome, 35.4% met both APS and GRD criteria, and 29.1% met criteria for the Brief Limited Intermittent Psychotic Symptoms (BLIPS) category. The total sample (N=97) had a good representation of both genders (60.8% male), was ethnically diverse (60.8% non-Hispanic White), and had a mean of 11.4 years of education (high-school). Age ranged from 12 to 27 in the NC group, 12 to 30 in the AR group, and 13 to 34 in the FE group. Adolescent subjects age 16 and younger (N=31) were included in the analyses and were represented in 25% of the FE group, 33.3% of the AR group, and 34.5% of the NC group. 22.9% of the AR and 10% of the FE subjects had a first-degree relative with psychosis.

Six (12.5%) of the 48 AR subjects transitioned to psychosis within the follow-up period or up to 18 months after entry into the study. Compared to the AR sample as a whole, the AR subjects who later converted to psychosis were more likely to have abused drugs and to have been treated with an antipsychotic medication prior to conversion to psychosis (Haroun et al., 2006). In fact, only 33.3% of them were not taking any psychiatric medications at baseline. Five of the 6 AR subjects who transitioned to psychosis did so after the follow-up neurocognitive testing, while one subject transitioned at one month in the study. The mean time to conversion of these subjects was 10.7 months. Two of them converted to schizophrenia, two to psychotic mania, one was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, and one with psychosis NOS. They were all males and had a mean age of 20.2 ± 2.9 years at follow-up.

Procedure

Details about sample ascertainment have been presented elsewhere (Eastvold et al., 2007). In brief, subjects were recruited through health services and public schools/colleges in the community of San Diego. In order to be included in the CARE program, subjects had to meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria summarized in Table 1. Subjects who met DSM-IV criteria for lifetime substance abuse/dependence were not excluded from the sample unless they had abused substances in the month prior to baseline cognitive testing. 31.2% of the AR group and 45% of the FE group had a lifetime history of alcohol and/or drug abuse. Subjects who fit the preliminary entry criteria based on a telephone screening underwent an extensive intake diagnostic interview and were followed up every month for clinical assessment. Qualifying participants also completed a battery of neurocognitive tests at baseline and then at six-month intervals. The AR subjects, just like the FE subjects, were ambulatory, treatment seeking, and were receiving treatment as usual (pharmacological and/or psychosocial) according to their presenting symptoms. Fourteen out of the 20 FE subjects (70%) and 10 out of the 48 AR subjects (20.8%) were on at least one antipsychotic with or without other psychotropic medications at baseline. The medicated AR subjects tended to have lower GAF scores than the unmedicated AR subjects, while the medicated FE subjects tended to be younger and less symptomatic than the unmedicated FE subjects. Five additional AR and three FE subjects were prescribed an antipsychotic between baseline and follow-up while four AR subjects who were on medications initially discontinued them before the second testing. None of the patients were involved in cognitive remediation although some were participating in group/supportive therapy or vocational rehabilitation but were at various stages of treatment during the course of the study.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Group | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| At-Risk (AR) | Recent onset (< 1 year) of subsyndromal psychotic symptoms per SIPS First-degree relative with schizophrenia or diagnosis of schizotypal personality disorder plus a recent deterioration in functioning |

History of head injury (loss of consciousness > 15 minutes or neurological sequelae) Substance abuse within the past month Neurological disorder IQ below 80 |

| First Episode (FE) | First psychotic episode within the past year DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia |

(Same as AR group) |

| Normal Controls (NC) | Comparable to AR and FE subjects with respect to age, ethnicity, and parental education |

(Same as AR and FE groups) Personal history of mental illness or learning disability Cluster A personality disorder or evidence of prodromal symptoms Family history of psychotic illness History of taking psychotropic medications |

Measures

Clinical Measures

The Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS; Miller et al., 2003) was used to assess prodromal symptoms. The at-risk subjects were identified according to the CARE prodromal criteria that slightly differ from the SIPS criteria in the required frequency and duration of symptoms (Ballon et al., 2007). Axis I and Axis II diagnoses were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID I; First et al., 1996) and the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SIDP; Pfohl et al., 1995) respectively. The Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS; Chambers et al., 1985) was administered to approximately a third of the sample which consisted of all subjects under the age of 16. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) were used to further evaluate clinical symptoms in AR and FE groups. Family history of psychiatric illness was assessed in all cases, after receiving consent to contact a relative, using the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria (Andreasen et al., 1977). Current level of functioning was assessed with the Modified Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF-M; Hall & Parks, 1995). The highest GAF score from the past year was determined retrospectively.

Neurocognitive Measures

The neurocognitive battery was part of a larger battery of tests that included psychophysiological measures of brain inhibitory functioning, as well as measures of attention and visual information processing. The neurocognitive battery was designed to minimize practice effects over repeated administration (e.g., use of different forms of the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised at baseline and follow-up) and assess five different neurocognitive domains: processing speed (PS), working memory (WM), verbal learning (VL), executive functioning (EF) and general intelligence (IQ) (Table 2). Neurocognitive domains were used instead of individual tests in order to reduce the number of statistical comparisons. Contributing variables for each domain were chosen on a theoretical basis (Eastvold et al., 2007). The small sample size in this study did not allow for confirmation of the factor structure underlying each of the domains. However, these neurocognitive domains were identified based on demonstrated impairments in schizophrenia spectrum populations (e.g., Cadenhead et al., 1999). Verbal learning was the only domain represented by a single test, i.e., the HVLT-R total recall over three trials, as we had to drop the HVLT-R delayed recall subtest from the analyses because of its ceiling effects. After normalizing all nine neurocognitive variables using a log transformation method, standardized scores were computed for both time points based on the baseline mean and standard deviation of the normal comparison group: (individual subject score – mean of NC group)/SD of NC group. The z-scores for WCST Perseverative Responses and Numerical Attention were inverted so that higher scores were indicative of better performance. Finally, composite scores for each neurocognitive domain – except for verbal learning that consisted of only one variable – were created by averaging the z-scores of contributing variables using equal weights. A global neurocognitive performance index was then created by averaging the five composite variables after ensuring that they were all normally distributed. Adolescents were combined with adults in order to maximize sample size, and the WISC-III Vocabulary and Block Design subtests were used in lieu of the WAIS-III for subjects younger than age 16. Standardized scores for the IQ domain were created separately for the > 16 and ≤ 16 age groups relative to the NC group. Two FE and two AR subjects were dropped from the analyses because they had missing baseline or follow-up scores on the verbal learning or processing speed domains.

Table 2.

Neurocognitive Measures

| Neurocognitive Domains | Measures |

|---|---|

| Executive Functioning (EF) | WCST: Perseverative Responses total SCWT: Interference (total correct after 45 seconds) |

| Processing Speed (PS) | NA (total completion time) SCWT: Color Naming (total number named within 45 seconds) |

| Verbal Learning (VL) | HVLT-R: Total Recall (number of correct words recalled after 3 presentations of a 12-word list) |

| Working Memory (WM) | WAIS-III: Letter Number Sequencing (total number correct) WMS-III: Spatial Span backwards |

| General Intelligence (IQ) | WAIS/WISC-III: Vocabulary total WAIS/WISC-III: Block Design total |

Note. WCST = Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (Heaton et al., 1993); SCWT = Stroop Color and Word Test (Golden, 1978); NA = Numerical Attention (Franklin et al., 1988); HVLT-R = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised (Benedict & Zgaljardic, 1998); WAIS-III = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Third Edition (Wechsler, 1997); WISC-III = Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – Third Edition (Wechsler, 1991); WMS-III = Wechsler Memory Scale – Third Edition (Wechsler, 1997).

Statistical Analyses

Demographic differences between groups were analyzed using Pearson Chi-Square tests (for discrete variables) and analyses of variance (for continuous variables). The test-retest reliability of each neurocognitive domain was examined by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficients. Repeated measures analyses of variance were also conducted to compare the patterns of change in performance over time among the three groups on each of the five neurocognitive domains as well as the global neurocognitive index. Post-hoc analyses were performed with Bonferroni corrections.

These data were also analyzed using the simple regression model that can quantify real changes in neurocognitive performance for individual cases, while accounting for confounding factors such as practice effects, normal test-retest variability, and regression to the mean. Based on this statistical method, the predicted follow-up score of an individual comes from the equation generated when follow-up scores are regressed on baseline scores of the normal comparison group (McSweeny et al., 1993). Then, confidence intervals (CI) are established around the discrepancies between predicted score and obtained score. Using the regression method on each domain, it was possible to determine if a disproportionate number of subjects improved (equal to or better than top 5% of CI) or worsened (equal to or worse than 5% of CI).

Change in symptom severity and level of functioning was assessed within each clinical group via repeated measures analyses of variance, which were followed by bivariate correlations to examine whether neurocognitive changes were associated with changes in clinical symptoms or GAF scores. Finally, we examined how the AR subjects who transitioned to psychosis differed from those who did not in terms of their neurocognitive performance over time.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Comparisons between the three groups on the socio-demographic variables revealed no significant group differences in age, education, parental education, ethnicity, or handedness. However, there were significantly more males than females in the FE group compared to the AR and NC groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics

| Normal Controls (N=29) |

At-Risk (N=46) |

First Episode (N=18) |

F/χ2 Tests | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean/SD) | Baseline: Follow-Up: |

19.0 (5.2) 19.9 (5.2) |

18.7(4.2) 19.8(4.1) |

20.1 (5.7) 21.0 (5.7) |

F(2,94)=.63 | .53 |

| Gender (% male) | 48.3% | 58.3% | 85% | χ2(2)=6.95 | <.05 | |

| Ethnicity (% Caucasian) | 58.6% | 60.4% | 65% | χ2(24)=20.03 | .69 | |

| Handedness (% right) | 89.7% | 89.1% | 75% | χ2(4)=6.67 | .15 | |

| Education (mean/SD) | 11.9 (4.4) | 11.2 (2.8) | 11.4 (2.8) | F(2,94)=.38 | .68 | |

| Parental Education (mean/SD) | 16.1 (2.3) | 15.5 (2.3) | 15.3 (2.9) | F(2,87)=.72 | .49 | |

| Follow-Up Interval (mean/range in months) |

12 (6-36) | 20.5 (6-36) 14.6 (6-36) | ||||

Test-Retest Reliability of Neurocognitive Domains

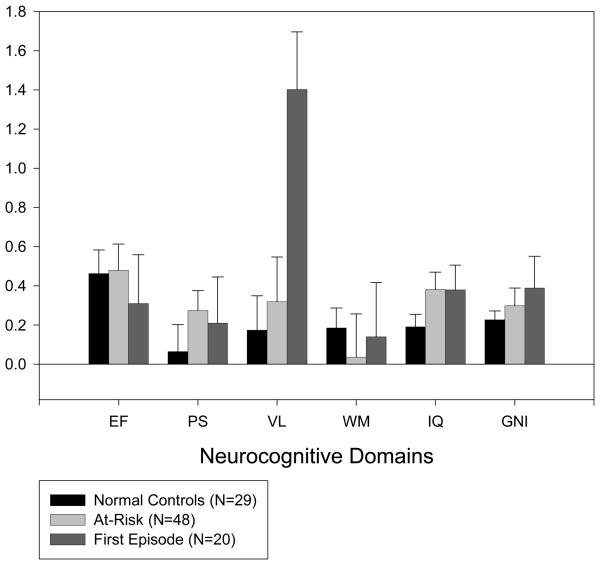

The means and standard deviations for the individual tests, as well as the standardized scores for the neurocognitive domains are reported in Tables 4 and 5 respectively. Performance between baseline and 6-month follow-up was fairly stable with moderate to high intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) across domains for all groups combined (.78 for executive functioning, .87 for processing speed, .75 for verbal learning, .65 for working memory, .93 for general intelligence, and .88 for the global neurocognitive index). Table 5 shows the ICC (using the z-scores) for each domain in each group separately. Mean z-score differences (follow-up – baseline) were computed for each group and are displayed in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Group Means and Standard Deviations for Neurocognitive Measures at Baseline and Follow-Up

| Neurocognitive Measures 1 | Baseline | Follow-Up | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Controls (N=29) | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| WCST Perseverative Responses | 7.4 | 3.7 | 5.1 | 2.5 |

| SCWT Interference | 44.3 | 8.4 | 45.8 | 10.1 |

| Numerical Attention | 168.8 | 37.3 | 168.4 | 59.0 |

| SCWT Color Naming | 71.8 | 12.5 | 74.0 | 12.6 |

| HVLT-R Total Recall | 27.8 | 3.5 | 28.5 | 4.0 |

| WAIS-III Letter Number Sequencing | 12.2 | 3.4 | 13.0 | 3.2 |

| WMS-III Spatial Span Backwards | 9.0 | 1.5 | 9.2 | 1.8 |

| WAIS/WISC-III Vocabulary | 47.5 | 9.4 | 48.9 | 8.4 |

| WAIS/WISC-III Block Design | 48.6 | 11.8 | 50.9 | 11.3 |

| At-Risk (N=48) | ||||

| WCST Perseverative Responses | 10.4 | 8.1 | 7.5 | 5.4 |

| SCWT Interference | 43.2 | 11.3 | 45.3 | 10.6 |

| Numerical Attention | 195.1 | 62.6 | 185.3 | 56.1 |

| SCWT Color Naming | 68.4 | 11.7 | 70.9 | 11.8 |

| HVLT-R Total Recall | 26.3 | 4.8 | 27.6 | 5.2 |

| WAIS-III Letter Number Sequencing | 10.6 | 2.5 | 11.6 | 2.9 |

| WMS-III Spatial Span Backwards | 8.3 | 2.2 | 8.19 | 2.3 |

| WAIS/WISC-III Vocabulary | 41.4 | 12.2 | 44.6 | 11.1 |

| WAIS/WISC-III Block Design | 45.3 | 11.4 | 49.9 | 12.4 |

| First Episode (N=20) | ||||

| WCST Perseverative Responses | 11.7 | 7.9 | 10.1 | 8.2 |

| SCWT Interference | 36.6 | 7.9 | 37.4 | 8.2 |

| Numerical Attention | 220.1 | 95.6 | 208.5 | 84.2 |

| SCWT Color Naming | 61.4 | 10.2 | 63.4 | 11.1 |

| HVLT-R Total Recall | 21.8 | 4.5 | 25.6 | 4.4 |

| WAIS-III Letter Number Sequencing | 10.3 | 2.2 | 10.6 | 2.4 |

| WMS-III Spatial Span Backwards | 7.6 | 2.0 | 7.8 | 1.9 |

| WAIS/WISC-III Vocabulary | 36.5 | 9.7 | 39.5 | 10.3 |

| WAIS/WISC-III Block Design | 41.2 | 13.3 | 45.2 | 14.0 |

See acronym definitions in Table 2.

Table 5.

Standardized Scores on Neurocognitive Domains Per Group at Baseline and Follow-Up

| Neurocognitive Domains | Baseline | Follow-Up | ICC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Controls (N=29) | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | r |

| Executive Functioning | −.01 | .75 | .45 | .72 | .75 |

| Processing Speed | .01 | .85 | .08 | 1.18 | .85 |

| Verbal Learning | .02 | 1.01 | .19 | 1.13 | .76 |

| Working Memory | 0 | .81 | .18 | .83 | .87 |

| General Intelligence | 0 | .86 | .19 | .75 | .95 |

| Global Index | 0 | .65 | .22 | .63 | .96 |

| At-Risk (N=48) | |||||

| Executive Functioning | −.39 | 1.18 | .08 | 1.01 | .79 |

| Processing Speed | −.52 | 1.15 | −.23 | 1.09 | .89 |

| Verbal Learning | −.48 | 1.53 | −.16 | 1.81 | .73 |

| Working Memory | −.64 | 1.28 | −.56 | 1.54 | .57 |

| General Intelligence | −.52 | 1.03 | −.12 | .99 | .90 |

| Global Index | −.51 | .91 | −.20 | .91 | .86 |

| First Episode (N=20) | |||||

| Executive Functioning | −.97 | 1.03 | −.49 | 1.22 | .69 |

| Processing Speed | −.93 | 1.31 | −.65 | 1.29 | .81 |

| Verbal Learning | −1.94 | 1.74 | −.54 | 1.36 | .78 |

| Working Memory | −.87 | .95 | −.48 | .79 | .42 |

| General Intelligence | −1.05 | 1.26 | −.62 | 1.26 | .94 |

| Global Index | −1.07 | .70 | −.56 | .77 | .70 |

Figure 1.

Mean z-score differences (follow-up – baseline) and standard errors for each group. The higher the difference score, the better the performance at follow-up. EF = executive functioning; PS = processing speed; VL = verbal learning; WM = working memory; IQ = general intelligence; GNI = global neurocognitive index.

Pattern of Change in Neurocognitive Performance at the Group Level

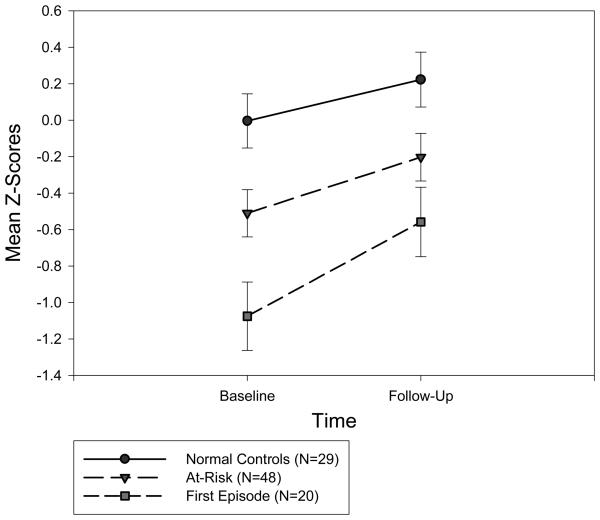

The repeated measures ANOVA for the global neurocognitive index showed significant group main effects averaged across time, as well as significant improvement over time averaged across groups, but no significant group by time interactions. Based on post-hoc comparisons, both the FE (p<.001) and AR (p=.03) groups performed significantly worse than the NC group in overall neurocognitive functioning. As predicted, the AR group's overall performance over time (M=−.35) fell between the FE (M=−.82) and NC (M=.11) groups' performance (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overall neurocognitive performance, as measured by the global neurocognitive index, at baseline and follow-up for each group. The bars represent the standard errors.

The repeated measures ANOVA across the individual ability domains revealed significant group main effects (averaged across time) in all domains. The FE group performed significantly worse than both the AR (p=.046) and NC (p=.003) groups in verbal learning. The FE group also performed significantly worse than the NC group in executive functioning (p=.002), processing speed (p=.03), and general intelligence (p=.01). Both the AR (p=.01) and FE (p=.04) groups had a significantly poorer performance in working memory than the NC group. Time effects (averaged across groups) were significant for all domains except working memory (Table 6).

Table 6.

Statistics for the Repeated Measures ANOVA

| Neurocognitive Domain | Group Effects | Time Effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(2,90) | P | Partial η2 | F(1,90) | P | Partial η2 | |

| Executive Functioning | 6.02 | .004 | .12 | 24.57 | <.001 | .21 |

| Processing Speed | 3.53 | .033 | .07 | 5.86 | .018 | .06 |

| Verbal Learning | 5.72 | .005 | .11 | 17.66 | <.001 | .16 |

| Working Memory | 5.07 | .008 | .10 | 2.65 | .11 | .03 |

| General Intelligence | 5.14 | .008 | .10 | 31.35 | <.001 | .26 |

| Global Index | 8.57 | .001 | .16 | 35.36 | <.001 | .28 |

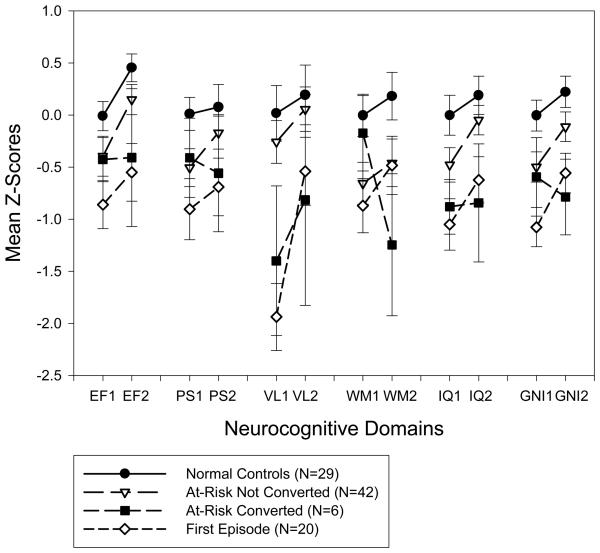

Group by time interaction was only significant for verbal learning (F[1,90]=5.25, p=.01, partial η2 =.10). Post-hoc tests revealed significant differences between the FE group and both the NC (p=.01) and AR (p=.01) groups. Figure 3 shows that while the NC and AR groups remained essentially stable over time in their verbal learning performance, the FE group significantly improved in that domain. Because of group differences in gender distribution, the same analyses were repeated with the addition of gender as a between-subjects variable. There were no significant gender by group, gender by time, or gender by group by time interactions.

Figure 3.

Pattern of performance over time and across domains for each group, including the subgroup of at-risk subjects who converted to psychosis and the one who did not. EF = executive functioning; PS = processing speed; VL = verbal learning; WM = working memory; IQ = general intelligence; GNI = global neurocognitive index; 1 = baseline; 2 = follow-up. The bars represent the standard errors.

Please note that all 48 AR subjects, including those who converted to psychosis over time, were included in the analyses reported above. The results did not change when we excluded the 6 converters and performed the same analyses. We also conducted a repeated measures ANOVA, as an exploratory analysis, to compare the subgroup that converted (AR-C, n=6) to the one that did not (AR, n=42) and found a significant group by time interaction in working memory, (F[1,44]=4.09, p=.049, partial η2 =.08). While the nonconverters remained stable over time in their working memory performance, the AR-C group significantly deteriorated in that domain (Figure 3).

Pattern of Change in Neurocognitive Performance at the Individual Level

Our objective was to go beyond group mean comparisons by assessing meaningful changes in individual patients within each of the AR and FE groups. Given our small sample sizes, those analyses were conducted in a strictly exploratory manner. In order to determine for each patient whether the difference between baseline and follow-up domain and total scores represented a meaningful change or a normal variability/fluctuation in performance, we employed a regression based statistical approach that has been used in neuropsychological research and found to have fairly good specificity and sensitivity in detecting change (Heaton et al., 2001). This prediction approach adjusts for practice effects and regression to the mean with repeated assessment by using linear regression of follow-up scores on baseline scores in the normal comparison group to generate a formula for predicting a follow-up score from any baseline score. Then, it estimates the expected range of follow-up performance on each domain based on a 90% confidence interval. The latter is the predicted score +/− (1.64 × SEresidual) where SEresidual is the standard deviation of the residual from the regression equation of the NC group.

Based on results shown in Table 7, a greater proportion of AR subjects than predicted fell outside the confidence interval on the general intelligence domain, showing a trend toward improvement that was not accounted for by practice effects and regression to the mean. Two of the AR subjects who converted to psychosis (AR-C) performed worse than expected over time on the working memory and processing speed domains. As for the FE subjects, a large proportion showed a deterioration in working memory, processing speed, executive functioning, and general intelligence. Yet, a high percentage of FE subjects tended to show an improvement in the verbal learning domain above what would be expected based on practice, which is consistent with the interaction effect obtained through the repeated measures ANOVA.

Table 7.

Test-Retest Changes beyond what is Expected from the Simple Regression Model

| Neurocognitive Domain | Better than 90% CI | Worse than 90% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR (N=42) |

AR-C (N=6) |

FE (N=20) |

AR (N=42) |

AR-C (N=6) |

FE (N=20) |

|

| Executive Functioning | 2.4% | 0% | 5.0% | 2.4% | 16.7% | 20.0% |

| Processing Speed | 7.1% | 0% | 5.3% | 2.4% | 33.3% | 21.1% |

| Verbal Learning | 7.5% | 0% | 31.6% | 7.5% | 16.7% | 5.3% |

| Working Memory | 11.9% | 0% | 5.0% | 16.7% | 33.3% | 20.0% |

| General Intelligence | 21.4% | 16.7% | 10.0% | 9.5% | 16.7% | 20.0% |

| Global Index | 2.4% | 0% | 0% | 2.4% | 16.7% | 10.0% |

Note. Predicted score = intercept + (unstandardized regression coefficient × baseline score); 90% CI (confidence interval) = predicted score +/− (1.64 × SEresidual); SEresidual = standard deviation of residual from regression equation of NC group; equations: CI = .31 + (.58 × baseline) +/− 1.29 for EF; CI = .15 + (.75 × baseline) +/− 1.05 for PS; CI = .18 + (.69 × baseline) +/− 1.45 for VL; CI = .18 + (.79 × baseline) +/− .85 for WM; CI = .19 + (.81 × baseline) +/− .48 for IQ; CI = .17 + (.75 × baseline) +/− .98 for GNI; AR = At-Risk Not Converted; AR-C = At-Risk Converted.

Associations between Change in Neurocognitive Performance and Clinical/Social Functioning Change

Repeated measures ANOVA showed significant improvements in symptom rating measures (BPRS, SAPS, SANS) and GAF scores in both patient groups. The AR subjects significantly improved in all their SIPS ratings (Table 8).

Table 8.

Clinical and Social Functioning Ratings at Baseline and Follow-Up

| At-Risk (N=48) | Baseline | F/U | F(1,47) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAF (mean/SD) | 52.1 (9.6) | 61.2 (10.9) | 23.75 | <.001 |

| BPRS (mean/SD) | 15.6 (5.9) | 9.6 (7.4) | 27.79 | <.001 |

| SAPS (mean/SD) | 5.4 (3.1) | 2.9 (2.8) | 28.41 | <.001 |

| SANS (mean/SD) | 6.2 (3.9) | 4.5 (3.9) | 10.01 | .003 |

| SIPS Total (mean/SD) | 34.3 (15.1) | 16.1 (12.3) | 30.41 | <.001 |

| SIPS Positive (mean/SD) | 10.8 (5.0) | 3.8 (3.9) | 27.54 | <.001 |

| SIPS Disorganized (mean/SD) | 6.2 (4.0) | 3.5 (3.5) | 24.32 | <.001 |

| SIPS Negative (mean/SD) | 10.9 (6.9) | 6.1 (5.6) | 26.67 | <.001 |

| SIPS General (mean/SD) | 6.5 (4.3) | 2.7 (3.3) | 23.10 | <.001 |

| First Episode (N=20) | Baseline | F/U | F(1,19) | P |

| GAF (mean/SD) | 42.5 (9.5) | 51.7 (7.6) | 17.55 | .001 |

| BPRS (mean/SD) | 20.4 (7.2) | 11.7 (6.8) | 19.78 | <.001 |

| SAPS (mean/SD) | 8.6 (4.6) | 5.2 (3.7) | 8.53 | .009 |

| SANS (mean/SD) | 9.1 (4.7) | 6.4 (4.3) | 9.86 | .005 |

In order to determine whether the changes observed in neurocognitive performance were related to changes in functional outcomes, we created difference scores for the neurocognitive, clinical, and functioning variables and performed Pearson's correlations between those difference scores within each patient group. Improvement in the global neurocognitive index was associated with improvement in SIPS positive symptoms in the AR group (r=−.36, p=.02) and GAF in the FE group (r=.34), although the latter correlation was not statistically significant (p=.15). There were additional modest but nonsignificant correlations between the verbal learning improvement in the FE group and improvement in BPRS (r=−.32) and SAPS (r=−.38).

Discussion

Our study is among the first to examine the course of neurocognitive functioning in the putative prodrome and first episode of schizophrenia using a matched normal comparison group to control for practice effects. The groups were comparable with respect to age, ethnicity, handedness, education, and parental education, although there was a higher proportion of males in the FE group. Neurocognitive functioning was found to be relatively stable in all groups, with moderate practice effects and moderate to high test-retest correlations across domains. The repeated measures ANOVA showed significant group and time main effects for the global neurocognitive index. The AR group's overall performance fell between the NC and FE groups' performance. There were significant group differences in all individual ability domains, significant time effects for executive functioning, processing speed, verbal learning, and general intelligence, as well as a significant group by time interaction for verbal learning. The FE group demonstrated a significant improvement in the verbal learning domain over the test-retest interval. The addition of gender as a grouping variable did not change the results.

For each individual subject, it was determined whether the observed fluctuations represented meaningful changes or normal variability in performance. After adjusting for both practice effects and regression to the mean using the simple regression model, a higher than expected percentage of AR subjects showed a real improvement in general intelligence. Moreover, a sizable proportion of the FE group demonstrated improvement in verbal learning above and beyond practice effects. While there was no statistically significant decline over time in any of the domains (based on the analyses conducted at the group level), some of the AR subjects who later converted to psychosis showed a deterioration in working memory and processing speed. Similarly, a higher than expected number of FE subjects fell outside the expected distribution in the working memory, processing speed, executive functioning, and general intelligence domains, showing a trend toward worsening despite overall improvement in clinical symptoms and social functioning.

Although these results need replication with larger sample sizes, they suggest that cognitive functions do not follow a unidimensional trajectory in schizophrenia, but rather vary by cognitive domain and position in the course of the illness. This multidimensional picture raises the possibility of more specific treatment targets in the future. For instance, cognitive remediation therapy might be effective in slowing down the declines in working memory and executive functioning during the early stages of schizophrenia (Demily & Franck, 2008). Processing speed could also be amenable to cognitive remediation strategies even before the onset of psychosis (Sartory et al., 2005).

While the neuropsychological deficits tend to be fairly stable in chronic schizophrenia (e.g., Harvey et al., 2005; Heaton et al., 2001), our findings suggest that there may be more changes during the prodromal period and right after the illness sets in. Furthermore, those early changes in overall neurocognitive functioning seem to occur in tandem with changes in positive symptom severity in the AR group. The substantial improvement in clinical symptoms and GAF scores over time in the AR group highlights that the at-risk state can be transient in many young people and that cognitive changes may be difficult to detect in this context. In contrast with investigations showing a decline in IQ prior to the onset of illness (Gochman et al., 2005), a significant proportion of AR subjects demonstrated an improvement in general intelligence over the 6-month follow-up, even after accounting for practice effects and regression to the mean. Given that our patients are treatment seeking, their baseline performance might have been very poor to start with. Although ascertainment bias tends to be more of an issue at baseline than with respect to change over time, it is possible that this factor might have contributed to the neuropsychological gains in the AR group.

Another important finding is that the FE group showed a considerable improvement in verbal learning despite the fact that we employed alternative forms of the HVLT-R as well as norms for change based on the regression model. The improvement in global cognition and verbal learning in the FE group was associated with an amelioration in functioning and clinical symptomatology, respectively. However, those correlations did not reach statistical significance because of the rather small sample size. Our results are inconsistent with Hoff et al. (1999)'s study in which verbal memory showed significantly less improvement in first-episode patients over time relative to that of comparison subjects. In the future, it may help to rule out statistical artifact by comparing this group's pattern of performance over time to that of a group of chronic schizophrenia patients with similar baseline levels of performance on verbal learning. However, we believe that regression to the mean is an unlikely explanation for this finding given that the FE group did not show remarkably large improvements in executive functioning, processing speed, and general intelligence, three domains on which they were substantially worse at baseline.

It is important to note though that subjects with poor baseline performance tend to have greater variation over time than initial high scorers and show more improvement consistent with regression to the mean. Thus, confidence intervals might need to be adjusted for different levels of baseline test performance (e.g., longer width for those who perform poorly at baseline) (Temkin et al., 1999). Alternatively, more complex models that take into account baseline level of IQ or education can be used, despite the fact that Goldberg et al. (2007) found no evidence that reading level, gender, and age are significant predictors of the magnitude of cognitive gain in first-episode schizophrenia patients. Also, it is uncertain whether norms for change, no matter what statistical model they are based on, can generalize from non-clinical to clinical groups. Therefore, future research will benefit from improving the available normative standards for quantifying real changes in neurocognitive performance for individual cases, while accounting for potentially confounding factors such as practice effects, test-retest reliability issues, and regression to the mean.

There is evidence to suggest that the emergence of schizophrenia is associated with CNS synaptic pruning and a dynamic wave of tissue loss (Rapoport et al., 2005). Children and adolescents with schizophrenia show an acceleration of gray matter loss, starting in parietal cortices and spreading to include temporal and frontal lobe structures as the disease progresses (Jacobsen et al., 1998; Thompson et al., 2001). This pathological process likely predates the onset of frank symptoms (Pantelis et al., 2003) and could help explain the working memory decline detected in a large number of AR and FE subjects. Longitudinal brain imaging studies using the same neurocognitive domains and with comparison groups similar to ours may provide insight into the biological mechanisms underlying the changes we detected.

Certain limitations of this study – namely its naturalistic design, single follow-up over a relatively short period, and modest sample sizes, including the control group – require special consideration. While longer-range studies with larger samples are clearly needed, these limitations should be viewed together with the fact that longitudinal assessment in such hard-to-recruit samples is quite challenging and large studies of this type are currently lacking. Progress in this area therefore requires incremental contributions of progressively longer-term multisite studies, which should be able to determine, for instance, whether those patients who initially show neurocognitive changes, stabilize with time or fluctuate back toward their own mean. Perhaps a more serious caveat of the study design was its lack of control over treatment effects that likely confounded our results given that over two-thirds of the FE sample and about one-fifth of the AR sample were using antipsychotic medications at baseline. In fact, the medicated AR subjects were the poorer functioning ones while the FE subjects who were not compliant with their medications had significantly more severe negative symptoms and tended to be older. On one hand, the possible contribution of treatment to the performance gains above and beyond practice effects in some domains cannot be logically excluded. However, a recent randomized clinical trial by Goldberg et al. (2007) demonstrated that the rates of improvement across most neurocognitive domains in first-episode schizophrenia patients on either Risperidone or Olanzapine did not exceed the practice effects in healthy controls. Moreover, this study found small differential medication effects and no significant associations between the magnitude of cognitive change scores and medication dose. On the other hand, the deterioration in working memory performance in some of our FE patients, as well as the AR patients who converted, might have been due to the initiation of treatment with atypical antipsychotic agents (Reilly et al., 2006). Testing the effect of treatment on change in neurocognitive performance in this highly unstable period was not feasible given that patients had various acuteness levels and had been on antipsychotics for different lengths of time (days to months). Yet, when we included treatment as another grouping factor in the analyses, we found no significant treatment by group by time interaction. As McGorry et al. (2008) highlighted, early psychosis researchers have often allowed treatment to vary widely in their studies, minimizing this major weakness of the naturalistic design. Therefore, large samples and randomized controlled trials are needed to carefully assess treatment effects on the progression or amelioration of neurocognitive impairments in the prodrome and first episode of schizophrenia, as well as the relationship to outcome measures such as psychotic conversion.

Preliminary inspection of our few AR subjects who transitioned to psychosis revealed that they had the most drastic decline in working memory and processing speed. Given that there is scant research in this area, those findings are important to report although the small sample size of our converted group does not allow us to determine whether a worsening in the aforementioned domains represents a true predictor of psychotic conversion. Yet, among the five neurocognitive domains we studied, change in working memory and processing speed performance stands out as a possible risk factor that could be added to the risk prediction algorithm developed by the North American Prodromal Longitudinal Studies (NAPLS) consortium (Cannon et al., 2008). It would be useful to explore the extent to which deterioration in those aspects of neurocognitive functioning improves sensitivity and predictive accuracy relative to other known risk factors of conversion to psychosis, such as functional decline, severity of subsyndromal psychotic symptoms (Haroun et al., 2006), and cannabis abuse (Kristensen and Cadenhead, 2007). Surprisingly, the group that developed psychosis had a similar or slightly better level of performance in the processing speed and working memory domains at baseline, relative to the AR group that did not convert. This underscores the importance of examining change over time as well as the advantage of longitudinal designs over cross-sectional ones. One caveat is that five of the six converters transitioned to psychosis after the 6-month follow-up period (i.e., at 10, 12 or 18 months) and we did not have 18-month follow-up data on all the AR subjects who participated in the study. Given the relatively brief length of follow-up, the as yet unknown term limit on “at-risk” status, and the treatment confound inherent to a naturalistic design, we cannot consider the subjects who did not convert to psychosis over the 6-month follow-up “false-positives”, as we expect that additional subjects might have converted if they were followed beyond the study duration. Future research examining the patterns of change in neurocognition in larger at-risk samples and over longer follow-up periods will help better characterize the converters from those who do not transition to psychosis or who develop a psychological disorder other than schizophrenia. While the latter group might improve in their state-related deficits with time, the true “prodromal” individuals may be more likely to stay stable or show a deterioration in their pre-existing cognitive weaknesses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH60720, K24 MH076191). The authors would like to acknowledge Nasra Haroun, M.D., Ali Eslami, M.D., and Karin Kristensen, Psy.D., for their clinical expertise, as well as Kathy Shafer, B.S., Iliana Marks, B.S., and Jason Nunag, B.S., for their help with recruitment, testing, and data management.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/nue.

References

- Addington J, Saeedi H, Addington D. The course of cognitive functioning in first episode psychosis: Changes over time and impact on outcome. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;78:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albus M, Hubmann W, Mohr F, Hecht S, Hinterberger-Weber P, Seitz N, et al. Neurocognitive functioning in patients with first-episode schizophrenia: results of a prospective 5-year follow-up study. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2006;256(7):442–451. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0667-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando J, Ono Y, Wright MJ. Genetic structure of spatial and verbal working memory. Behavior Genetics. 2001;31(6):615–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1013353613591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Winokur G. The family history method using diagnostic criteria: Reliability and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1977;34(10):1229–35. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770220111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballon JS, Kaur T, Marks II, Cadenhead KS. Social functioning in young people at risk for schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2007;151(1-2):29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RH, Zgaljardic DJ. Practice effects during repeated administrations of memory tests with and without alternate forms. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1998;20(3):339–52. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.3.339.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder RM, Goldman RS, Robinson D, Reiter G, Bell L, Bates JA, et al. Neuropsychology of first-episode schizophrenia: Initial characterization and clinical correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:549–59. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder RM, Reiter G, Bates J, Lencz T, Szeszko P, Goldman RS, et al. Cognitive development in schizophrenia: Follow-back from the first episode. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2006;28:270–82. doi: 10.1080/13803390500360554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer WJ, Francey SM, Wood SJ, Jackson HJ, Pantelis C, Phillips LJ, et al. Memory impairments identified in people at ultra-high risk for psychosis who later develop first-episode psychosis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(1):71–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenhead KS. Vulnerability markers in the schizophrenia spectrum: implications for phenomenology, genetics, and the identification of the schizophrenia prodrome. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2002;25(4):837–53. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenhead KS, Perry W, Shafer K, Braff DL. Cognitive functions in schizotypal personality disordered subjects. Schizophrenia Research. 1999;37:123–32. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, Woods SW, Addington J, Walker E, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: A multi-site longitudinal study in North America. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65(1):28–37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD, Zorrilla LE, Shtasel D, Gur RE, Gur RC, Marco EJ, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in siblings discordant for schizophrenia and healthy volunteers. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51(8):651–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950080063009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Censits DM, Ragland D, Gur RC, Gur RE. Neuropsychological evidence supporting a neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: a longitudinal study. Schizophrenia Research. 1997;24:289–298. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(96)00091-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers WJ, Puig-Antich J, Hirsch M, Paez P, Ambrosini PJ, Tabrizi MA, et al. The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semistructured interview. Test-retest reliability of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children, present episode version. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42:696–702. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300064008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosway R, Byrne M, Clafferty R, Hodges A, Grant E, Abukmeil SS, et al. Neuropsychological change in young people at high risk for schizophrenia: results from the first two neuropsychological assessments of the Edinburgh High Risk Study. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30(5):1111–21. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demily C, Franck N. Cognitive remediation: a promising tool for the treatment of schizophrenia. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2008;8(7):1029–36. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.7.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastvold AD, Heaton RK, Cadenhead KS. Neurocognitive deficits in the (putative) prodrome and first episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;93(1-3):266–77. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Seidman LJ, Kremen WS, Toomey R, Pepple JR, Tsuang MT. Neuropsychological functioning among the nonpsychotic relatives of schizophrenic patients: A 4-year follow-up study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108(1):176–81. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. User's guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Research Version (SCID-I) Version 2.0. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Franklin GM, Heaton RK, Nelson LM, Filley CM, Seibert C. Correlation of neuropsychological and MRI findings in chronic/progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1998;38(12):1826–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.12.1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gochman PA, Greenstein D, Sporn A, Gogtay N, Keller B, Shaw P, et al. IQ stabilization in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;77(2-3):271–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold S, Arndt S, Nopoulos P, O'Leary DS, Andreasen NC. Longitudinal study of cognitive function in first-episode and recent-onset schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(9):1342–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg TE, Goldman RS, Burdick KE, Malhotra AK, Lencz T, Patel RC, et al. Cognitive improvement after treatment with second-generation antipsychotic medications in first-episode schizophrenia. Is it a practice effect? Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1115–22. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden CJ. Stroop Color and Word Test. Stoelting; Chicago, IL: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood TA, Braff DL, Light GA, Cadenhead KS, Calkins ME, Dobie DJ, et al. Initial heritability analyses of endophenotypic measures for schizophrenia: the consortium on the genetics of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(11):1242–50. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.11.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall RC, Parks J. The modified global assessment of functioning scale: addendum. Psychosomatics. 1995;36(4):416–7. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(95)71656-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroun N, Dunn L, Haroun A, Cadenhead KS. Risk and protection in prodromal schizophrenia: Ethical implications for clinical practice and future research. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32(1):166–78. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Palmer BW, Heaton RK, Mohamed S, Kennedy J, Brickman A. Stability of cognitive performance in older patients with schizophrenia: An 8-week test-retest study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(1):110–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins KA, Addington J, Keefe RS, Christensen B, Perkins DO, Zipurksy R, et al. Neuropsychological status of subjects at high risk for a first episode of psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;67(2-3):115–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, Kay GG, Curtiss G. Wisconsin Card Sort Test, Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Gladsjo JA, Palmer BW, Kuck J, Marcotte TD, Jeste DV. Stability and course of neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:24–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Temkin N, Dikmen S, Avitable N, Taylor MJ, Marcotte TD, et al. Detecting change: A comparison of three neuropsychological methods, using normal and clinical samples. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2001;16:75–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs R, Zakanis K. Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: A quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology. 1998;12(3):426–45. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff AL, Sakuma M, Wieneke M, Horon R, Kushner M, DeLisi LE. Longitudinal neuropsychological follow-up study of patients with first-episode schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(9):1336–41. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff AL, Svetina C, Shields G, Stewart J, DeLisi LE. Ten year longitudinal study of neuropsychological functioning subsequent to a first episode of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;78:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen LK, Giedd JN, Castellanos FX, Vaituzis AC, Hamburger SD, Kumra S, et al. Progressive reduction of temporal lobe structures in childhood-onset schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:678–85. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.5.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce EM, Hutton SB, Mutsatsa SH, Barnes TRE. Cognitive heterogeneity in first-episode schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;187:516–22. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.6.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RS, Perkins DO, Gu H, Zipursky RB, Christensen BK, Lieberman JA. A longitudinal study of neurocognitive function in individuals at-risk for psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2006;88:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen K, Cadenhead KS. Cannabis abuse and risk for psychosis in a prodromal sample. Psychiatry Research. 2007;151:151–4. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lencz T, Smith CW, McLaughlin D, Auther A, Nakayama E, Hovey L, et al. Generalized and specific neurocognitive deficits in prodromal schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59(9):863–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loebel AD, Lieberman JA, Alvirl JMJ, Mayerhoff DI, Geisler SH, Szymanski SR. Duration of psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:1183–1188. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Yung AR, Bechdolf A, Amminger P. Back to the future: Predicting and reshaping the course of psychotic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65(1):25–7. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSweeny AJ, Naugle RI, Chelune GJ, Luders H. “T scores for change”: An illustration of a regression approach to depicting change in clinical neuropsychology. Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1993;7:300–12. [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Cadenhead K, Cannon T, Ventura J, et al. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: Predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2003;29(4):703–15. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niendam TA, Bearden CE, Zinberg J, Johnson JK, O'Brien M, Cannon TD. The course of neurocognitive and social functioning in individuals at ultra high risk for psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33(3):772–81. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nopoulos P, Flashman L, Flaum M, Arndt S, Andreasen N. Stability of cognitive functioning early in the course of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 1994;14:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen KA, Rosenbaum B. Prospective investigations of the prodromal state of schizophrenia: review of studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113(4):247–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelis C, Velakoulis D, McGorry PD, Wood SJ, Suckling J, Phillips LJ, et al. Neuroanatomical abnormalities before and after onset of psychosis: A cross-sectional and longitudinal MRI comparison. Lancet. 2003;361(9354):281–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. The Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV) Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa; Iowa City, Iowa: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Posthuma D, Mulder EJ, Boomsma DI, de Geus EJ. Genetic analysis of IQ, processing speed and stimulus-response incongruency effects. Biological Psychology. 2002;61(1-2):157–82. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(02)00057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukrop R, Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Bechdolf A, Brockhaus-Dumke A, Klosterkotter J. Neurocognitive indicators for a conversion to psychosis: Comparison of patients in a potentially initial prodromal state who did or did not convert to a psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;92(1-3):116–25. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport JL, Addington AM, Frangou S, Psych MR. The neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: update 2005. Molecular Psychiatry. 2005;10(5):434–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly JL, Harris MSH, Keshavan MS, Sweeney JA. Adverse effects of Risperidone on spatial working memory in first-episode schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:1189–97. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rund BR, Landro NI, Orbeck AL. Stability in cognitive dysfunctions in schizophrenic patients. Psychiatry Research. 1997;69(2-3):131–41. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(96)03043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rund BR, Melle I, Friis S, Johannessen JO, Larsen TK, Midboe LJ, et al. The course of neurocognitive functioning in first-episode psychosis and its relation to premorbid adjustment, duration of untreated psychosis, and relapse. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;91:132–40. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartory G, Zorn C, Groetzinger G, Windgassen K. Computerized cognitive remediation improves verbal learning and processing speed in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;75(2-3):219–23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeber K, Cadenhead KS. How does studying schizotypal personality disorder inform us about the prodrome of schizophrenia? Current Psychiatry Reports. 2005;7:41–50. doi: 10.1007/s11920-005-0024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temkin NR, Heaton RK, Grant I, Dikmen SS. Detecting significant change in neuropsychological test performance: A comparison of four models. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 1999;5:357–69. doi: 10.1017/s1355617799544068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PM, Vidal C, Giedd JN, Gochman P, Blumenthal J, Nicolson R, et al. Mapping adolescent brain change reveals dynamic wave of accelerated gray matter loss in very early-onset schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(20):11650–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201243998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 3rd Edition. (WISC-III) The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, Tex: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Third Edition. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, Texas: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale - Third Edition. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, Texas: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte M, Brett C, Harrison LK, Byrne M, Miller P, Lawrie SM, et al. Neuropsychological performance over time in people at high risk of developing schizophrenia and controls. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59:730–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodberry KA, Giuliano AJ, Seidman LJ. Premorbid IQ in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(5):579–87. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1996;22(2):353–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, McGorry PD. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;67:131–142. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, Phillips LJ, Kelly D, Dell'Olio M, et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39(11-12):964–71. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]