Abstract

The progesterone (P4) rise on proestrous afternoon is associated with dephosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and reduced TH activity in the stalk-median eminence (SME), which contributes to the proestrous prolactin surge in rats. In the present study, we investigated the time course for P4 effect on TH activity and phosphorylation state, as well as cAMP levels and protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) activity and quantity, in the SME on proestrous morning and afternoon. P4 (7.5 mg/kg, sc) treatment on proestrous afternoon decreased TH activity and TH phosphorylation state at Ser-31 and Ser-40 within 1h, whereas morning administration of P4 had no 1h effect on TH. PP2A activity in the SME was enhanced after P4 treatment for 1h on proestrous afternoon without a change in PP2A catalytic subunit quantity, whereas P4 treatment had no effect on PP2A activity or quantity on proestrous morning. Cyclic AMP levels in the SME were unchanged with 1h P4 treatment. At 5h after P4 treatment, TH activity and phosphorylation state declined coincident with an increase in plasma prolactin in both P4-treated morning and afternoon groups. PP2A activity in the SME was unchanged in 5h P4-treated rat. Our data suggest that P4 action on tuberoinfundibular dopaminergic neurons involves at least two components. A more rapid (1h) P4 effect engaged only on proestrous afternoon likely involves activation of PP2A. The longer P4 action on tuberoinfundibular dopaminergic neurons is evident on both the morning and afternoon of proestrus and may involve a common, as yet unidentified, mechanism.

Keywords: tuberoinfundibular dopaminergic neurons, prolactin, estrous cycle, ovariectomy

Introduction

A preovulatory prolactin surge is evident on proestrous afternoon in rats (Liu & Arbogast 2008; Smith et al. 1975). The rising titer of estradiol beginning late on diestrous day 2 and continuing into proestrous morning is essential for the occurrence of the prolactin surge and drives the early phase of the surge (Neill et al. 1971; Arbogast & Ben-Jonathan 1990). The preovulatory rise in progesterone (P4) on proestrous afternoon augments the magnitude or extends the duration of this prolactin surge (Arbogast & Ben-Jonathan 1990; Arbogast & Voogt 1994; Liu & Arbogast 2008). This proestrous prolactin surge may have a luteolytic role to maintain the estrous cycle (Gaytan et al. 2001).

Dopamine is the major inhibitor of prolactin release from the anterior pituitary gland (Ben-Jonathan & Hnasko 2001; Freeman et al. 2000). Dopamine is released from tuberoinfundibular dopaminergic (TIDA) neurons, which originate in the arcuate nucleus and project to the median eminence. Dopamine synthesis is dependent on the activity of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), which is the rate-limiting enzyme in the catecholaminergic biosynthetic pathway. In response to a positive stimulus, TH enzyme is rapidly phosphorylated, resulting in increased hydroxylation of tyrosine to 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) and its instant conversion to dopamine (Haycock & Haycock 1991). TH can be phosphorylated at four serine sites, Ser-8, Ser-19, Ser-31 and Ser-40, in the N-terminal regulatory domain of TH. Each serine site is the target of specific protein kinase(s) and phosphoprotein phosphatase(s) and the phosphorylation state of TH results from the dynamic balance between these opposing actions.

An inhibitory action of P4 on TIDA neurons contributes to P4 enhancing effect on the preovulatory prolactin surge. A decrease in TH activity and TH mRNA levels occurs concomitantly with the preovulatory P4 rise (Arbogast & Ben-Jonathan 1989; Arbogast & Voogt 1994; Liu & Arbogast 2008). Acute ovariectomy on proestrous morning prevents this decline in TH activity and TH mRNA levels. P4, but not estradiol, replacement at the appropriate time restores the decline in TH activity, as well as the increase in circulating prolactin levels (Arbogast & Ben-Jonathan 1990; Arbogast & Voogt 1994). The P4 rise on proestrous afternoon is associated with decreased phospho-TH at Ser-19, Ser-31 and Ser-40 as early as 1700h and extending to at least 2200h (Liu & Arbogast 2008). Ser-40, a target of cAMP-dependent protein kinase, exhibits the most marked dephosphorylation changes, suggesting that this site may exert the greatest impact on TH activity. In ovariectomized rats primed with estradiol, P4 given early in the morning exerts an inhibitory effect on TIDA neuronal activity (Yen & Pan 1998) and augments prolactin secretion (Caligaris et al. 1974) after 4–5h. P4 decreases the number of detectable TH mRNA-containing cells in the arcuate and periventricular regions between 2h and 8h after treatment (Morrell et al. 1989). A reduction in the quantity of TH protein was observed within 1 day after P4 treatment (Wang & Porter 1986).

The concerted dephosphorylation of TH at Ser-19, Ser-31 and Ser-40 induced by endogenous and exogenous P4 administration (Liu & Arbogast 2008) supports the notion that a common phosphatase mechanism may be involved. Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) acts on these serine sites (Haavik et al. 1989: Berresheim & Kuhn 1994) and thus is a potential mediator. The objective for this study was to examine the time course for P4 effect on plasma prolactin levels, TH activity and TH phosphorylation state in the stalk-median eminence (SME) during proestrous morning and afternoon. These data will provide insight into the mechanism(s) that may be involved in the endogenous P4 action on TIDA neurons on proestrus. We also evaluated the effect of P4 administration on PP2A and cAMP levels in the SME of rats on proestrous morning and afternoon, to explore the cellular mechanism underlying P4 modulation of TIDA neurons.

Materials and Methods

Animals and experimental groups

Adult female (200–250g) Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from Charles River (Raleigh, NC). Rats were housed under controlled temperature and lighting (lights on from 0700h-2100h) and supplied with food and water ad libitum. Estrous cycles were followed by daily vaginal lavage, and only those displaying at least three consecutive 4-day estrous cycles were used. Experiments were performed in the rats on diestrus-2 and/or proestrus. All animal experiments were conducted according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale.

Some rats were implanted with a chronic jugular cannula on diestrus-2 under isoflurane anesthesia. Where indicated, ovariectomy was performed under isoflurane anesthesia between 1200h and 1400h on proestrus. Rats were treated with P4 (7.5 mg/kg, sc) or oil (1 ml/kg) at 0930h or at 1700h on proestrus. This dose for P4 decreased TH mRNA level and enzyme activity in the TIDA system in our previous studies (Arbogast & Ben-Jonathan 1990; Arbogast & Voogt 1994; Liu & Arbogast 2008). To examine the effect of ovariectomy and P4 replacement on prolactin secretion in proestrous rats, blood samples (0.25ml) were collected from 1300h–2200h at 1h interval in normal cycling rats, sham-operated rats and ovariectomized (1200h–1230h) rats treated with oil vehicle or P4 at 1700h. To evaluate the time course for exogenous P4 regulation of plasma prolactin and compare the different effect between proestrousmorning and afternoon, blood samples (0.6 ml) were collected at 0h, 1h, 3h, 5h after treatment, i.e. at 0930h, 1030h, 1230h and 1430h after proestrous morning injections or at 1700h, 1800h, 2000h and 2200h after proestrous afternoon injections. Blood was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min and plasma was stored at −20°C for subsequent determination of P4 and/or prolactin levels. To examine P4 effects on TH activity, TH phosphorylation state, cAMP level, PP2A enzyme activity and protein levels in the SME, groups of rats were treated with P4 or oil and sacrificed at 1h, 3h or 5 h after treatment. SME tissue was dissected with fine scissors using a dissecting microscope and frozen immediately on dry ice. The tissue was then stored at −80°C until analysis for TH activity by HPLC, phospho-TH and catalytic subunit of PP2A protein level by Western blot, PP2A activity assay and cAMP level by RIA within 1 week.

Estimation of TH activity by HPLC

DOPA accumulation in the SME was used as an index of TH activity. Briefly, rats were injected with m-hydroxybenzylhydrazine dihydrochloride (NSD 1015; 100mg/kg, ip), an L-aromatic amino acid decarboxylase inhibitor, and decapitated 30 min thereafter. The dissected SME tissue was homogenized by sonication in 250 μl 0.1 N perchloric acid and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min. DOPA content in the supernatant was determined by HPLC with electrochemical detection, as described previously (Arbogast & Voogt 1991, 1994; Liu & Arbogast 2008). The pellet was solubilized in 0.5 N sodium hydroxide and analyzed for protein content with the Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Tissue DOPA levels were normalized to protein contents.

Western Blot for phospho-TH and catalytic subunit of PP2A (PP2Ac) protein

SME tissue was sonicated in 35 μl homogenization buffer and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min, as previously described (Liu & Arbogast 2008). A 2.5 μl aliquot of the supernatant was used for protein content determination using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay. An equivalent amount of Laemmli sample buffer (Sigma Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol was added to each supernatant and samples were heated to 95°C for 4 min. Equal amounts of protein (10–25 μg) from each experimental sample were loaded to individual wells on an 8% polyacrylamide gel. Gels were calibrated with molecular weight standards between 49 and 211 kDa. The proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrophoretically transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. For measuring the phosphorylation state of TH, the membranes were incubated in 0.2% I-Block (Tropix, Bedford, MA) in PBS for 1h to block non-specific binding, and then immunoblotted using one of the following antisera combinations diluted in 1% BSA-PBS-T (0.05% Tween-20 in PBS) overnight at 4°C: 1) rabbit anti-phospho-TH at Ser-19 (1:2500, 36-9800, Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA) and mouse anti-TH (1:3000, MAB 318, Chemicon International, Temecula, CA); 2) rabbit anti-phospho-TH at Ser-31 (1:2500, 36-9900, Zymed Laboratories) and mouse anti-TH (1:3000); 3) rabbit anti-phospho-TH at Ser-40 (1:2500, 36-8600, Zymed Laboratories) and mouse anti-TH (1:3000); 4) rabbit anti-TH (1:3000, AB152, Chemicon International) and mouse anti-β-tubulin (1:4000, Upstate Biotechnology, Temecula, CA). For determining catalytic subunit of PP2A (PP2Ac) levels in the SME, the membrane was incubated with rabbit anti-PP2Ac (1:2500, 06-222, Upstate Biotechnology) and mouse anti-β-tubulin (1:4000). After incubation with primary antisera, membranes were washed in PBS-T and incubated with both IRDye® 800 Conjugated Affinity Purified anti-mouse IgG (1:20,000, 610-132-003, Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA) and Alexa Fluor 680 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:20,000, A-21109, Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) for 40 min, as described previously (Liu & Arbogast 2008). The respective proteins were detected with Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR, Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). Protein band intensities were quantified using the associated ArrayPro® Analyzer 4.5 Software. All samples for each experiment were included on 2 blots and control samples on each blot were averaged and data expressed as percent control.

PP2A activity assay

PP2A activity assay was carried out using the Serine/Threonine Phosphatase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) with minor modifications. Briefly, SME tissue was homogenized in 50μl ice-cold lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, 10μg/ml leupeptin, 10μg/ml aprotinin, 10μg/ml pepstatin A, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol). The homogenate was centrifuged for 1h at 40,000 × g to remove particulate matter. Sephadex columns were used to remove free phosphate from the supernatant. Protein concentrations in the phosphate-free tissue lysate were determined using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay. PP2A activity was determined by measuring the generation of free phosphate from the phosphopeptide RRA(pT)VA using the molybdate-malachite green-phosphate complex assay as described by the manufacturer. For a control experiment, PP2A assay buffer containing no substrate or 10 μM okadaic acid was used for the enzyme reaction. After a 20-min incubation at 30 °C, the reaction was terminated by adding 50 μl of Molybdate Dye/Additive mixture and the 96-well plate was incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The PP2A activity was quantified by measuring the optical density at 630 nm using a BioTek Synergy 2 microplate reader (Fisher Scientific, St. Louis, MO). The optical density value was quantified using the associated Gen5™ software, and adjusted by the optical density obtained from the no substrate control samples. The amount of phosphate released in the reaction was calculated from a curve of phosphate standards run in parallel. The effective range for the detection of phosphate released in this assay is 100–4000 pmol of phosphate.

P4 and prolactin levels in plasma and cAMP level in the SME detected by RIA

Plasma P4 concentrations were measured using Coat-A-Count kit (Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, CA) with a sensitivity of 0.02 ng/ml. The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 6.5% and 11.9%, respectively. Plasma prolactin levels were assessed using a RIA kit provided by Dr. Albert Parlow and the National Hormone and Pituitary Program. Prolactin RP-3 was used as a reference preparation and the limit of sensitivity for the assay was 0.25 ng/ml. The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 7.6% and 9.3%, respectively. Cyclic AMP level in the SME tissue was measured by the cAMP RIA kit (Biomedical Technologies Inc., Stroughton, MA) with minor modifications. SME tissue was extracted by homogenization in ice cold 3% perchloric acid. The supernatant was collected after centrifuge, and small drops of a chilled 30% (w/v) solution of potassium bicarbonate were then added into the supernatant. After a second centrifuge, the supernatant was collected for the cAMP assay. The limit of sensitivity for cAMP assay was 1 pmol/ml or 0.005 pmol/tube.

Statistical Analysis

Plasma P4, plasma prolactin and TH activity data were evaluated by two-way ANOVA. When repeated samples were collected over time to analyze the P4 effect on the proestrous prolactin surge, plasma prolactin data were analyzed by a split-plot ANOVA. Multiple comparisons were made with Fisher’s least significant procedures. TH phosphorylation states, PP2A activity, PP2Ac protein and cAMP levels in the SME between P4 and oil vehicle treated rats were compared using Student’s t-test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant difference.

Results

Effect of ovariectomy and P4 replacement on the proestrous prolactin surge

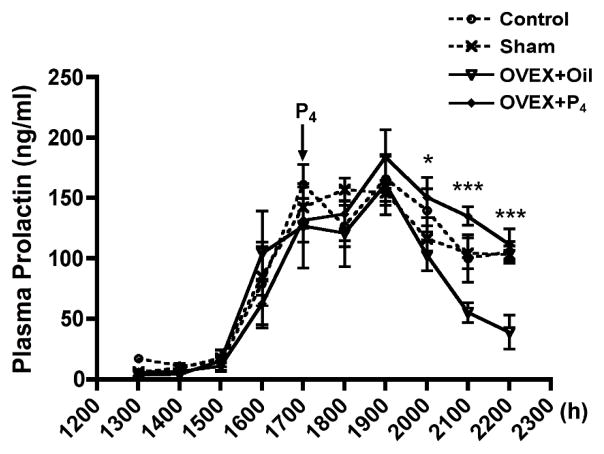

Plasma prolactin levels were evaluated in control, sham-operated, and ovariectomized rats treated with oil vehicle (1 ml/kg, sc) or P4 (7.5 mg/kg, sc) on proestrus to assess P4 contribution to prolactin secretion on proestrous afternoon (Fig. 1). Rats were ovariectomized at 1200h–1230h on proestrus to eliminate the endogenous P4 rise. P4 was restored by injection at 1700h. Plasma prolactin levels during the early phase (1600h–1900h) of the prolactin surge were similar in all groups. Circulating prolactin levels in ovariectomized rats were reduced (p<0.05) at 2100h–2200h on proestrous evening, as compared to sham-operated rats, whereas P4 administration to ovariectomized rats sustained prolactin secretion at a value similar to that of control or sham-operated rats. Circulating prolactin levels were higher (p<0.01) by 1.5-fold at 3h (2000h), 2.4-fold at 4h (2100h) and 2.9-fold at 5h (2200h) after P4 administration as compared to that of oil-treated ovariectomized rats. Prolactin secretion was similar in sham-operated and control rats, suggesting that anesthesia and surgical manipulations on mid-day proestrus did not alter the amplitude or duration of the prolactin surge.

FIG. 1.

Plasma prolactin levels in control, sham-operated, and ovariectomized rats treated with oil vehicle (1 ml/kg, sc) or P4 (7.5 mg/kg, sc) on proestrus. Ovariectomy was performed at 1200h–1230h, and P4 was injected at 1700h on proestrous afternoon. Sham-operation (n=7) did not influence prolactin secretion as compared with that of the control (n=6). P4 administration (n=9) in the ovariectomized rats prolonged prolactin secretion at 3–5h later as compared to that of oil treatment (n=7). Each value represents a mean ± SEM. * p<0.05, *** p<0.001 vs. corresponding oil-treated ovariectomized rats.

Plasma P4 and prolactin levels in P4-treated rats

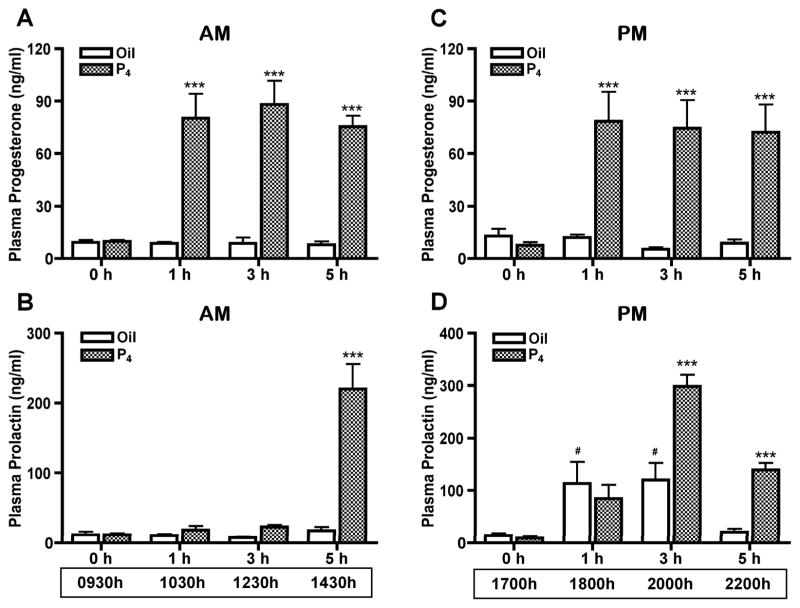

Plasma prolactin levels at 0h, 1h, 3h and 5h after P4 (7.5 mg/kg, sc) or vehicle oil (1 ml/kg) administration on proestrous morning and afternoon were examined to assess the time course of P4 effect on prolactin secretion. Rats included in the afternoon group were ovariectomized at 1200h–1400h on proestrus to eliminate the endogenous P4 rise. P4 administered at 0930h or 1700h on proestrus increased (p<0.001) plasma P4 concentration to 80 ng/ml within 1h and this P4 level was maintained for at least 5h (Fig. 2A and 2C). When P4 was administered on proestrous morning, the increased plasma P4 level did not alter circulating prolactin levels at 1h (1030h) and 3h (1230h) after P4 administration. However, plasma prolactin level was increased (p<0.001) 12.2-fold by 5h (1430h) after P4 treatment (Fig. 2B). The profile of circulating prolactin on proestrous afternoon is complex and P4 treatment augmented (p<0.001) the prolactin surge at 3h (2000h) and extended (p<0.001) the prolactin surge at 5h (2200h) after P4 treatment at 1700h. Notably, circulating prolactin levels were increased (p<0.05) by 2.5- and 6.6-fold at 3h (2000h) and 5h (2200h), respectively, compared to the oil-treated control (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

Plasma P4 (A, C) and prolactin (B, D) levels at 0h, 1h, 3h and 5h after morning (A, B) or afternoon (C, D) administration of P4 (7.5 mg/kg, sc) or sesame oil vehicle (1 ml/kg, sc). For the afternoon treatment groups (C, D), rats were ovariectomized at 1200h–1400h on proestrus. P4 administered at 0930h (n=10) or 1700h (n=8) on proestrus increased plasma P4 to 80 ng/ml within 1h and P4 levels remained high for at least 5h. Oil treatment (n=6 for each group) did not affect the plasma P4 level. After P4 treatment at 0930h (B), circulating prolactin levels were unchanged at 1h and 3h after P4 treatment, but increased 12.2-fold within 5h. After P4 treatment at 1700h (D), circulating prolactin levels were increased by 2.5-fold at 3h and 6.6-fold at 5h after P4 administration, compared to oil-treated control. Each value represents a mean ± SEM. *** p<0.001 vs. corresponding oil-treated control. # p<0.05 vs. oil treatment for 0h.

TH activity in the SME of P4-treated rats

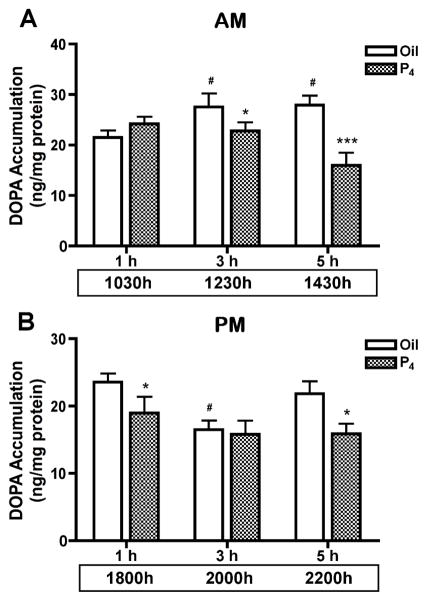

TH activity was evaluated by DOPA accumulation in the SME in P4-treated rats on proestrous morning and afternoon. TH activity was unaltered at 1h (1030h) after morning P4 treatment, but was decreased (p<0.05) by 16% at 3h (1230h) and 51% at 5h (1430h), compared to the oil-treated control. TH activity in the SME of vehicle oil-treated rats at 1230h and 1430h was higher (p<0.05) than that at 1030h (Fig. 3A). P4 administration at 1700h on proestrous afternoon exhibited a different profile. TH activity was decreased (p<0.05) by 17% at 1h (1800h) and by 32% at 5h (2200h) after the afternoon P4 administration. TH activity was lower (p<0.05) in the oil-treated group at 3h (2000h) as compared to the values at 1h (1800h) and 5h (2200h). P4 did not alter TH activity in the SME at 3h (2000h) after the afternoon treatment as compared to oil-treated control group (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

TH activity in the SME of rats at 1h, 3h and 5h after P4 or oil treatment at 0930h (A) or 1700h (B) on proestrus. TH activity in the SME was unaltered at 1h (n=8) after morning P4 treatment, but was decreased by 16% at 3h (n=8) and 51% at 5h (n=9). TH activity was increased in the 3h (n=10) and 5h (n=9) oil-treated groups compared to the 1h control (n=8). Rats were ovariectomized at 1200h–1400h on proestrus for the afternoon P4 treatment. P4 administration at 1700h decreased TH activity by 17% at 1h (n=12) and by 32% 5h (n=10) later as compared to the corresponding 1h control (n=14 and n=10, respectively). TH activity was reduced in the oil-treated group at 2000h in the 3h group, but there was no significant difference between oil- and P4-treated groups at 3h (n=11 each). Each value represents a mean ± SEM. * p<0.05, *** p<0.001 vs. corresponding oil-treated control. # p<0.05 vs. oil treatment for 1h.

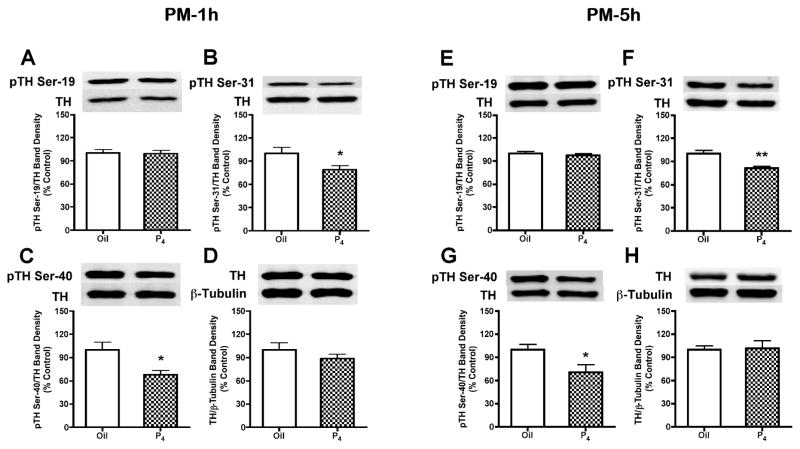

Phosphorylation state of TH in the SME of P4-treated rats

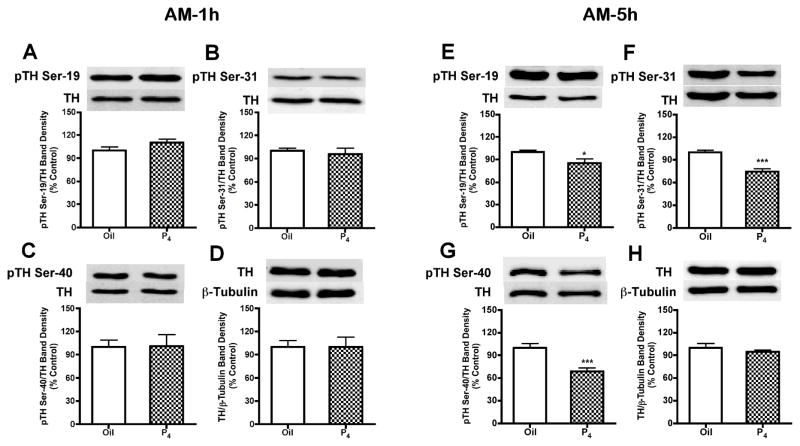

Consistent with TH activity data at 1h (1030h) after P4 treatment on proestrous morning, there were no differences in the phosphorylation state of TH at Ser-19, Ser-31 and Ser-40 at this time (Fig. 4A–D). However, at 5h (1430h) after morning P4 treatment, SME phospho-TH signals at Ser-19, Ser-31 and at Ser-40 were decreased by 14% (p<0.05), 26% (p<0.001) and 31% (p<0.001), respectively (Fig. 4E–H). In contrast to morning administration, P4 administration at 1700h decreased (p<0.05) phospho-TH signals at Ser-31 by 21% and Ser-40 by 32% within 1h (1800h), which suggests relatively rapid P4-dependent dephosphorylation of TH unique to proestrous afternoon (Fig. 5B and 5C). The phospho-TH signals at Ser-31 and Ser-40 remained reduced by 19% (p<0.05) and 29% (p<0.01), respectively, at 5h (2200h) after afternoon P4 administration (Fig. 5F and 5G). Phospho-TH at Ser-19 (Fig. 5A and 5E) was not altered 1h (1800h) or 5h (2200h) after P4 treatment on proestrous afternoon. TH protein quantity (Fig. 4D, 4H, 5D and 5H) and β-tubulin levels in the SME were not altered by 1h (1030h or 1800h) or 5h (1430h or 2200h) P4 treatment on proestrous morning or afternoon.

FIG. 4.

Phosphorylation state of TH at Ser-19, Ser-31 and Ser-40 within 1h (A–D) or 5h (E–H) after P4 or oil treatment on proestrous morning. A representative immunoblot for each phosphorylation site of TH or TH protein is displayed on top of the bar graph. Similar to TH activity data, there were no differences in the phosphorylation state of TH at Ser-19, Ser-31 and Ser-40 within 1h after P4 treatment at 0930h on proestrus. However, TH phosphorylation at Ser-19, Ser-31 and Ser-40 decreased by 14%, 26% and 31% at 5h later, respectively. Phospho-TH values were individually normalized to respective TH values. TH values were individually normalized to respective β-tubulin values. Each value represents a mean ± SEM of determinations of seven to eight rats. * p<0.05, *** p<0.001 vs. oil treatment.

FIG. 5.

Phosphorylation state of TH at Ser-19, Ser-31 and Ser-40 at 1h (A–D) or 5h (E–H) after P4- or oil- treatment on proestrous afternoon. A representative immunoblot for each phosphorylation site of TH, TH protein or β-tubulin is displayed on top of the bar graph. In contrast to morning administration, P4 treatment at 1700h significantly decreased TH phosphorylation at Ser-31 by 19–21% and Ser-40 by 29–32% at 5h and 1h, respectively. There were no significant differences between the P4- and oil-treated groups for Ser-19 phosphorylation, TH protein and β-tubulin levels. Phospho-TH values were individually normalized to respective TH values. TH values were individually normalized to respective β-tubulin values. Each value represents a mean ± SEM of determinations from seven (oil-treated) to eight (P4-treated) rats. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 vs. oil treatment.

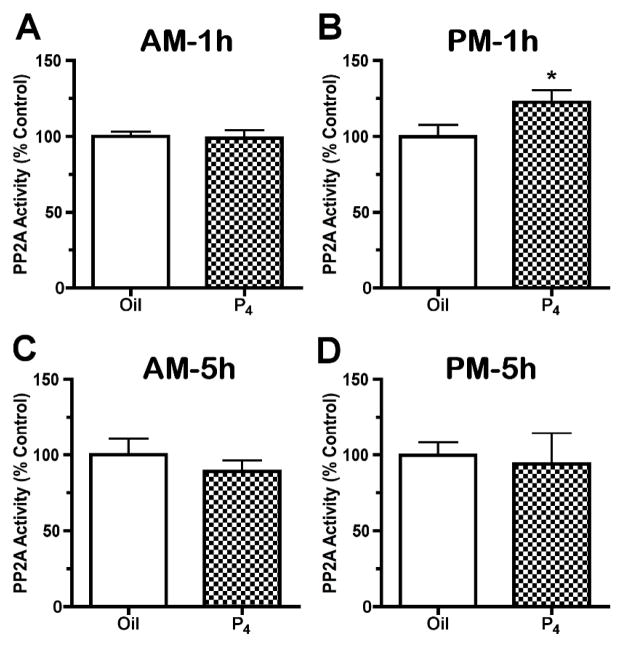

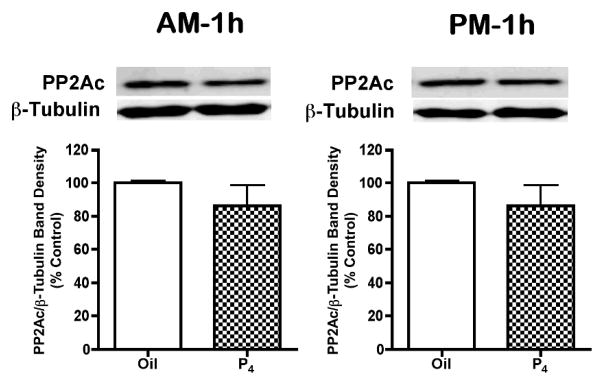

PP2A activity and PP2Ac protein levels in the SME of P4-treated rats

PP2A activity in the SME was not altered by P4 treatment on proestrous morning, but was increased by 22% at 1h (1800h) after P4 administration on proestrous afternoon (p<0.05, Fig. 6A and 6B). Okadaic acid (10μM), a PP2A inhibitor, completely abolished the phosphatase activity in the SME tissue (data not shown). In contrast to the 1h afternoon data, PP2A activity was not altered at 5h after P4 administration on proestrous morning or afternoon (Fig. 6C and 6D). There were no changes in PP2Ac quantities in the SME at 1h after P4 treatment on proestrous morning and afternoon (Fig. 7).

FIG. 6.

PP2A activity in the SME of rats regulated by P4 treatment for 1h (A, B) or 5h (C and D) on proestrous morning (A, C) and afternoon (B, D). P4 administration at 0930h did not alter PP2A activity in the SME of rats at 1h (A, n=9) and 5h (C, n=6) after the treatment on proestrous morning. However, afternoon P4 treatment significantly increased PP2A activity in the SME by 22% at 1h (B, n=9), but not 5h (D, n=6) later. Data are expressed as the mean percent change relative to oil-treated control ± SEM. * p<0.05 vs. oil-treated control.

FIG. 7.

Catalytic subunit of PP2A (PP2Ac) level in the SME of rat at 1h after P4 or oil treatment on proestrous morning and afternoon. A representative immunoblot for SME tissue reacted with PP2Ac and β-tubulin antibodies were displayed on top of the bar graph. PP2Ac values were individually normalized to respective β-tubulin values. Data are expressed as the mean percent change relative to oil- treated control ± SEM of determinations from six rats. No statistically significant difference was observed between the P4- and oil- treated rats on proestrous morning and afternoon.

cAMP levels in the SME of rats after P4 administration

Since phosphorylation of TH at Ser-40 site can be activated through cAMP-dependent protein kinase and Ser-40 exhibited the most marked dephosphorylation in our study, we examined cAMP levels in the SME after P4 treatment on proestrous morning and afternoon (n=6 each group). Cyclic AMP levels in the SME of oil-treated control groups were 200.64±18.13 and 202.70±17.85 pmol/mg protein at 1030h and 1800h, respectively. P4 administration for 1h did not change cAMP levels in the SME of rats on proestrous morning and afternoon. Cyclic AMP levels at 1h after P4 treatment were 195.18±13.27 and 201.70±10.48 pmol/mg protein at 1030h and 1800h, respectively.

Discussion

The major finding of this study is that P4 suppressed TH activity and TH phosphorylation state in TIDA neurons within 1h on proestrous afternoon. These changes in TH phosphorylation at Ser-40 and Ser-31 coincided with increased PP2A activity in the SME at 1h after P4 treatment on proestrous afternoon, suggesting that PP2A may induce TH dephosphorylation leading to a decline of TH activity. It is notable that 1h P4 treatment on proestrous morning did not alter TH activity, TH phosphorylation state or PP2A activity. However, P4 treatment at 0930h on proestrous morning and 1700h on proestrous afternoon suppressed TH activity and TH phosphorylation state in TIDA neurons 5h later, suggesting that a common mechanism may be engaged at the 5h time point. In contrast to an afternoon-specific effect on PP2A after 1h P4 treatment, P4 had no effect on PP2A activity in the SME on proestrous morning and afternoon at 5h, suggesting that additional factor(s) may arise to support TH dephosphorylation.

We previously reported that exogenous P4 administration at 0930h on proestrous morning decreased TH activity and increased serum prolactin level at 5h after P4 treatment (Liu & Arbogast 2008). Our current study addressed the time course for P4’s effects on TH activity in the SME and on plasma prolactin levels. On proestrous morning, the inhibitory P4 effect on TH activity and TH phosphorylation was delayed. It was only 5h after P4 treatment that a marked change in TH activity and TH phosphorylation was observed, which correlated with a 12.2-fold rise in plasma prolactin levels. These data are in agreement with earlier studies, which have shown that P4 given for 3h-6h can lower TIDA neuronal activity and increase prolactin levels (Babu & Vijayan 1984; Beattie, et al. 1972; Caligaris et al. 1974; Yen & Pan 1998).

Analysis of a P4 effect on proestrous afternoon is more complex due to hormonal changes during the preovulatory period. Our approach to understand P4 action has been a classical ablation-replacement approach where rats are intact on proestrous morning to allow for elevated estradiol levels, but ovariectomized in early afternoon to prevent the endogenous P4 rise. As in our previous studies using this paradigm (Arbogast & Ben-Jonathan 1989, 1990; Arbogast & Voogt 1994), acutely ovariectomized rats exhibited a blunted or truncated prolactin surge. This early phase of the proestrous prolactin surge in the acutely ovariectomized rats likely reflects an estradiol-dependent component of the prolactin surge driven by a prolactin-releasing factor(s) input, rather than decreased dopaminergic tone (Neill et al. 1971; Arbogast & Ben-Jonathan 1990; Murai et al. 1989; Samson et al. 1986; Kennett et al. 2009). P4 replacement to acutely ovariectomized rats amplified and extended the prolactin surge beyond an estradiol-dependent component. In contrast to morning P4 administration, P4 treatment at 1700h on proestrous afternoon decreased TH activity within 1h, although the decrease in TH activity did not functionally affect plasma prolactin levels at the onset of the surge. It is notable that a similar decrease in TH activity occurs concomitantly with the P4 rise on proestrous afternoon in intact animals and thus likely has physiological relevance (Liu & Arbogast 2008). This decrease in TH activity may be related to other hormonal events, which occur during this same time period on proestrous afternoon. Alternatively, this initial decrease in TIDA neuronal activity may set the stage for later P4-dependent amplification of the prolactin surge. A non-P4-dependent decline in TH activity in the SME occurred at 2000h in acutely ovariectomized rats. Thus, although TH activity of both control and P4-treated rats were lower than pre-surge levels, there was no significant difference between the two groups. This decrease may represent an endogenous rhythm in TIDA neuronal activity that occurs on every day of the estrous cycle in female rats (Mai, et al. 1994; Shieh & Pan 1996) and is apparent even in ovariectomized female rats (Lerant & Freeman 1997). Similar to the morning study, P4 administration induced a significant decline in TH activity and increase in plasma prolactin at 5h later. The similarity of response with respect to TH activity and TH phosphorylation state suggests that common mechanism(s) may exist on proestrous morning and proestrous afternoon at 5h after P4 administration.

The data in this study support and extend our previous observation (Arbogast & Ben-Jonathan 1990; Arbogast & Voogt 1994) that P4 plays an important role in extending the duration of the prolactin surge on proestrus and indicates a contribution of decreased TIDA neuronal activity. It is not clear if P4 administration recruits non-dopaminergic factors. However, a recent study (Kennett et al. 2009) indicates that while an oxytocin antagonist blocks the estradiol-induced prolactin surge, the oxytocin antagonist does not block the estradiol+P4-induced prolactin surge. These data suggest that P4 is acting through a mechanism independent of the prolactin-releasing activity of oxytocin. A change in pituitary sensitivity to dopamine cannot be discounted, since dynamic changes in anterior pituitary dopamine receptors and responsiveness to dopamine occur during the day of proestrus (Heiman & Ben-Jonathan 1982; Pasqualini et al. 1984; Brandi et al. 1990). Indeed, estradiol decreases pituitary sensitivity to dopamine, whereas P4 acts antagonistically to restore dopamine responsiveness (Bression et al. 1985; Pasqualini et al. 1986).

TH activation is regulated by long-term induction, including transcriptional regulation, alternative RNA splicing, RNA stabilization and translational regulation, and short-term activation through phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of the enzyme (Goldstein 2000). There are four serine sites (Ser-8, Ser-19, Ser-31 and Ser-40) in the N-terminal regulatory region of TH (Dunkley et al. 2004). The phosphorylation state of TH at any time is determined by interplay of protein kinases and phosphoprotein phosphatases. Ser-40 can be phosphorylated by a range of protein kinases, including protein kinase A, protein kinase C and calcium- and calmodulin-stimulated protein kinase II, protein kinase G, MAPK-activated protein kinases 1 and 2, p38-regulated/activated kinase and mitogen-and stress-activated protein kinase 1 (Dunkley et al. 2004). The kinases able to phosphorylate Ser-19 are calcium- and calmodulin-stimulated protein kinase II, p38-regulated/activated kinase and MAPK-activated protein kinase 2. ERK-1 and ERK-2, as well as cyclin-dependent kinase 5, phosphorylate TH at Ser-31 (Dunkley et al. 2004; Kansy et al. 2004). Although less is known about phosphatase action on TH, PP2A and PP2C dephosphorylate TH at Ser-19, Ser-31 and/or Ser-40 (Dunkley et al. 2004). Indeed, PP2A is responsible for approximately 90% of Ser-40 and Ser-19 phosphatase activity in adrenal extracts, and PP2C accounts for 10% of the phosphatase activity of Ser-40 and Ser-19 (Haavik et al. 1989). Similar results were found in the extracts from rat brain for Ser-40 (Berresheim & Kuhn 1994; Bevilaqua et al. 2003). PP2A, but not PP2C is able to dephosphorylate Ser-31 in both PC12 cells and bovine adrenal chromaffin cells (Haycock 1990; Leal et al. 2002). PP2A consists of a heterotrimer of a catalytic (C) subunits, a scaffolding A subunit and a variable regulatory B subunit (Dobrowsky et al. 1993; Kamibayashi et al. 1994).

P4 treatment administered on proestrous afternoon caused dephosphorylation of TH at Ser-40 and Ser-31 as early as 1h post-treatment. A similar decrease in radiolabeled phosphate incorporation into TH protein within 1h was observed in hypothalamic cells in vitro (Arbogast & Voogt 2002), although the specific serine sites were not identified in this earlier study. The concerted dephosphorylation of regulatory serines supports the notion of a common phosphatase mechanism. Indeed, the activity of PP2A, which is a major phosphatase for TH (Dunkley et al. 2004; Haavik et al. 1989), was increased coincident with the acute afternoon-specific dephosphorylation of TH at Ser-31 and Ser-40. The increase in PP2A activity was observed in SME tissue, which contains a mixed population of nerve terminals as well as cell bodies for various glial and neuronal cells. Thus, the 22% increase in total PP2A activity may actually reflect a more marked increase in P4 responsive cells or terminals in the SME. A role for a phosphatase being involved in P4 action is further supported by the fact that okadaic acid, a PP2A and PP1 inhibitor, reversed the P4-dependent decrease in radiolabeled phosphate incorporation into TH protein in hypothalamic cells in vitro (Arbogast & Voogt 2002). P4 did not alter PP2Ac protein level in the SME at 1h after P4 administration, suggesting activation of existing PP2Ac enzyme rather than production of new PP2Ac enzyme protein. Further studies are required to identify the mechanism by which P4 stimulates PP2A activity.

While our data support increased PP2A activity associated with the early proestrous afternoon-specific component of P4 action on TIDA neurons, our data indicate a differential mechanism between the 1h and 5h time point. The 5h mechanism was engaged on both the morning and afternoon of proestrus and was associated with increased prolactin secretion. Our current data confirm our previous study (Liu & Arbogast, 2008) that P4 administered on proestrous morning induced dephosphorylation of TH at Ser-40, Ser-31 and Ser-19 after 5h and extend this finding to proestrous afternoon. It was somewhat surprising that PP2A activity at 5h after P4 was similar to control values on proestrous morning and afternoon. Our previous data suggested a role for phosphatase involvement in P4 action since okadaic acid, a PP2A and PP1 inhibitor, reverses the dephosphorylation at 2200h on proestrus (Arbogast & Voogt 1994). However, the lack of change in PP2A activity does not support its involvement in TH dephosphorylation. Additional studies will be required to identify a P4-induced mechanism for the 5h time point. It may be that another phosphatase is recruited for this later time, the kinase component(s) of the signaling cascade are down-regulated or the initial dephosphorylation of TH induces a conformational changes which stabilizes dephosphorylated TH.

Exogenous P4 administration on proestrous afternoon caused dephosphorylation of TH at Ser-40 and Ser-31, but not Ser-19. Phosphorylation of TH at Ser-40 increases enzyme activity up to 20-fold and appears to be the main mechanism for short-term TH activation (Daubner et al. 1992; Dunkley et al. 2004), whereas Ser-31 phosphorylation produces a less than 2-fold increase in TH activity (Haycock et al. 1992). Ser-19 phosphorylation does not directly affect TH activity, but it may potentiate TH phosphorylation at Ser-40 and subsequent TH activation by binding to the 14:3:3 protein, or by hierarchical phosphorylation (Bevilaqua et al. 2001; Bobrovskaya et al. 2004; Dunkley et al. 2004; Haycock et al. 1998; Toska et al. 2002). In the current and previous study (Liu & Arbogast 2008), Ser-40 site exhibited the most marked dephosphorylation change at 5h after P4 treatment on proestrous morning and at 1h and 5h after P4 treatment on proestrous afternoon. These data suggest that the Ser-40 site, which is a critical target for cAMP-dependent protein kinase A, may exert the greatest impact on TH activity. To explore whether down-regulation of the cAMP signaling pathway may account for TH dephosphorylation at Ser-40 in the SME induced by P4, we examined cAMP levels in the SME tissue. However, no change of cAMP concentration was observed at 1h after P4 treatment on proestrous morning and afternoon. The mechanism(s) underlying P4-induced dephosphorylation at Ser-40 and other serine sites need further investigation.

P4 regulation of TH activity and prolactin secretion requires previous or concomitant treatment with estradiol (Arbogast & Ben-Jonathan 1990; Arbogast & Voogt 2002; Beattie et al. 1972; Gonzalez et al. 1980, Morrell et al. 1989) and estradiol stimulates P4 receptor expression (Kraus et al. 1994; Scott et al. 2002; Shughrue et al. 1997). Classical nuclear P4 receptors are found in dopaminergic neurons of hypothalamus in rats (Fox et al. 1990; Lonstein & Blaustein 2004; Sar 1988). This colocalization of P4 receptor and TH suggests that P4 may act directly on dopaminergic neurons in the hypothalamus. Further support for a direct P4 action within the hypothalamus is provided by an acute P4 inhibitory effect on TH activity in isolated hypothalamic cells (Arbogast & Voogt 2002). Our data support the notion that there are at least two components to P4 action on TIDA neurons with respect to dopamine synthesis. It is not clear which P4 receptor subtypes mediate these actions. The classical nuclear P4 receptor may act as a transcription factor in the nucleus or modulate intracellular signaling pathways outside the nucleus, whereas membrane P4 receptors may rapidly activate intracellular signaling pathway (Mani 2006; Thomas 2008). The more rapid P4 component is apparent on proestrous afternoon in this study and in estradiol-treated hypothalamic cells in vitro (Arbogast & Voogt 2002) and involves actions on cytoplasmic proteins, TH and PP2A. The timing and cellular localization for the 1h P4 effect is consistent with either P4 membrane receptor or classical P4 receptor in the cytoplasm, but does not preclude a P4-induced transcriptional change. The 5h P4 effect observed on both proestrous morning and afternoon involves both a decrease in TH phosphorylation as shown in this study as well as suppression of TH mRNA levels by 2200h on proestrus (Arbogast & Voogt 1994). The change in TH mRNA levels suggests that the classical nuclear P4 receptor may mediate at least part of this later component, although a dephosphorylation action on TH protein would indicate some action within the cytoplasm as well. The expression pattern for P4 receptor subtypes in the brain during the proestrous day may provide some clues as to which receptors mediates the components of P4 action on TIDA neurons during proestrus. Indeed, P4 receptor B, membrane P4 receptor α and membrane P4 receptor β mRNA expression is increased on proestrous afternoon and reaches the highest levels coincident with the preovulatory P4 rise (Liu & Arbogast 2009). Further investigation is needed to determine P4 receptor subtypes involved in P4 action on TIDA neurons and related transcription and non-transcription signaling mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. A. F. Parlow, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, and the National Hormone and Peptide Program, NIDDK, for providing prolactin RIA reagents.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest and funding

The authors have no conflict of interests to disclose. This work was support by NIH grants HD045805 and HD048925 to LAA.

Disclaimer. This is not the definitive version of record of this article. This manuscript has been accepted for publication in Journal of Endocrinology, but the version presented here has not yet been copy edited, formatted or proofed. Consequently, the Society for Endocrinology accepts no responsibility for any errors or omissions it may contain. The definitive version is now freely available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1677/JOE-09-0335. Copyright 2009 Society for Endocrinology.

References

- Arbogast LA, Ben-Jonathan N. Tyrosine hydroxylase in the stalk-median eminence and posterior pituitary is inactivated only during the plateau phase of the preovulatory prolactin surge. Endocrinology. 1989;125:667–674. doi: 10.1210/endo-125-2-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbogast LA, Ben-Jonathan N. The preovulatory prolactin surge is prolonged by a progesterone-dependent dopaminergic mechanism. Endocrinology. 1990;126:246–252. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-1-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbogast LA, Voogt JL. Hyperprolactinemia increases and hypoprolactinemia decreases tyrosine hydroxylase messenger ribonucleic acid levels in the arcuate nuclei, but not the substantia nigra or zona incerta. Endocrinology. 1991;128:997–1005. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-2-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbogast LA, Voogt JL. Progesterone suppresses tyrosine hydroxylase messenger ribonucleic acid levels in the arcuate nucleus on proestrus. Endocrinology. 1994;135:343–350. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.1.7912184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbogast LA, Voogt JL. Progesterone induces dephosphorylation and inactivation of tyrosine hydroxylase in rat hypothalamic dopaminergic neurons. Neuroendocrinology. 2002;75:273–281. doi: 10.1159/000057336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu GN, Vijayan E. Hypothalamic tyrosine hydroxylase activity and plasma gonadotropin and prolactin levels in ovariectomized-steroid treated rats. Brain Res Bull. 1984;12:555–558. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(84)90171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie CW, Rodgers CH, Soyka LF. Influence of ovariectomy and ovarian steroids on hypothalamic tyrosine hydroxylase activity in the rat. Endocrinology. 1972;91:276–279. doi: 10.1210/endo-91-1-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Jonathan N, Hnasko R. Dopamine as a prolactin (PRL) inhibitor. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:724–763. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.6.0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berresheim U, Kuhn DM. Dephosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase by brain protein phosphatases: a predominant role for type 2A. Brain Res. 1994;637:273–276. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevilaqua LR, Cammarota M, Dickson PW, Sim AT, Dunkley PR. Role of protein phosphatase 2C from bovine adrenal chromaffin cells in the dephosphorylation of phospho-serine 40 tyrosine hydroxylase. J Neurochem. 2003;85:1368–1373. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevilaqua LR, Graham ME, Dunkley PR, von Nagy-Felsobuki EI, Dickson PW. Phosphorylation of Ser(19) alters the conformation of tyrosine hydroxylase to increase the rate of phosphorylation of Ser(40) J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40411–40416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105280200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrovskaya L, Dunkley PR, Dickson PW. Phosphorylation of Ser19 increases both Ser40 phosphorylation and enzyme activity of tyrosine hydroxylase in intact cells. J Neurochem. 2004;90:857–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandi AM, Joannidis S, Peillon F, Joubert D. Changes of prolactin response to dopamine during the rat estrous cycle. Neuroendocrinology. 1990;51:449–454. doi: 10.1159/000125373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bression D, Brandi AM, Pagesy P, Le Dafniet M, Martinet M, Brailly S, Michard M, Peillon F. In vitro and in vivo antagonistic regulation by estradiol and progesterone of the rat pituitary domperidone binding sites: correlation with ovarian steroid regulation of the dopaminergic inhibition of prolactin secretion in vitro. Endocrinology. 1985;116:1905–1911. doi: 10.1210/endo-116-5-1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caligaris L, Astrada JJ, Taleisnik S. Oestrogen and progesterone influence on the release of prolactin in ovariectomized rats. J Endocrinol. 1974;60:205–215. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daubner SC, Lauriano C, Haycock JW, Fitzpatrick PF. Site-directed mutagenesis of serine 40 of rat tyrosine hydroxylase. Effects of dopamine and cAMP-dependent phosphorylation on enzyme activity. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12639–12646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrowsky RT, Kamibayashi C, Mumby MC, Hannun YA. Ceramide activates heterotrimeric protein phosphatase 2A. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15523–15530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkley PR, Bobrovskaya L, Graham ME, von Nagy-Felsobuki EI, Dickson PW. Tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation: regulation and consequences. J Neurochem. 2004;91:1025–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SR, Harlan RE, Shivers BD, Pfaff DW. Chemical characterization of neuroendocrine targets for progesterone in the female rat brain and pituitary. Neuroendocrinology. 1990;51:276–283. doi: 10.1159/000125350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman ME, Kanyicska B, Lerant A, Nagy G. Prolactin: structure, function, and regulation of secretion. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1523–1631. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaytan F, Bellido C, Morales C, Sanchez-Criado JE. Cyclic changes in the responsiveness of regressing corpora lutea to the luteolytic effects of prolactin in rats. Reproduction. 2001;122:411–417. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein M. Long- and short-term regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase. In: Meador-Woodruff JH, editor. Psychopharmacology. The American College of Psychoneuropharmacology; 2000. pp. 1–6. On-line ed., www.acnp.org. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez HA, Kedzierski W, Aguila-Mansilla N, Porter JC. Hormonal control of tyrosine hydroxylase in the median eminence: demonstration of a central role for the pituitary gland. Endocrinology. 1989;124:2122–2127. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-5-2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haavik J, Schelling DL, Campbell DG, Andersson KK, Flatmark T, Cohen P. Identification of protein phosphatase 2A as the major tyrosine hydroxylase phosphatase in adrenal medulla and corpus striatum: evidence from the effects of okadaic acid. FEBS Lett. 1989;251:36–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81424-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haycock JW. Phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase in situ at serine 8, 19, 31, and 40. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11682–11691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haycock JW, Ahn NG, Cobb MH, Krebs EG. ERK1 and ERK2, two microtubule-associated protein 2 kinases, mediate the phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase at serine-31 in situ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2365–2369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haycock JW, Haycock DA. Tyrosine hydroxylase in rat brain dopaminergic nerve terminals. Multiple-site phosphorylation in vivo and in synaptosomes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5650–5657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haycock JW, Lew JY, Garcia-Espana A, Lee KY, Harada K, Meller E, Goldstein M. Role of serine-19 phosphorylation in regulating tyrosine hydroxylase studied with site- and phosphospecific antibodies and site-directed mutagenesis. J Neurochem. 1998;71:1670–1675. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71041670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman ML, Ben-Jonathan N. Dopaminergic receptors in the rat anterior pituitary change during the estrous cycle. Endocrinology. 1982;111:37–41. doi: 10.1210/endo-111-1-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamibayashi C, Estes R, Lickteig RL, Yang SI, Craft C, Mumby MC. Comparison of heterotrimeric protein phosphatase 2A containing different B subunits. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20139–20148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansy JW, Daubner SC, Nishi A, Sotogaku N, Lloyd MD, Nguyen C, Lu L, Haycock JW, Hope BT, Fitzpatrick PF, et al. Identification of tyrosine hydroxylase as a physiological substrate for Cdk5. J Neurochem. 2004;91:374–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennett JE, Poletini MO, Fitch CA, Freeman ME. Antagonism of oxytocin prevents suckling- and estradiol-induced, but not progesterone-induced, secretion of prolactin. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2292–2299. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus WL, Montano MM, Katzenellenbogen BS. Identification of multiple, widely spaced estrogen-responsive regions in the rat progesterone receptor gene. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:952–969. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.8.7997237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal RB, Sim AT, Goncalves CA, Dunkley PR. Tyrosine hydroxylase dephosphorylation by protein phosphatase 2A in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Neurochem Res. 2002;27:207–213. doi: 10.1023/a:1014880403970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerant A, Freeman ME. Dopaminergic neurons in periventricular and arcuate nuclei of proestrous and ovariectomized rats: endogenous diurnal rhythm of Fos-related antigens expression. Neuroendocrinology. 1997;65:436–445. doi: 10.1159/000127207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Arbogast LA. Phosphorylation state of tyrosine hydroxylase in the stalk-median eminence is decreased by progesterone in cycling female rats. Endocrinology. 2008;149:1462–1469. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Arbogast LA. Gene expression profiles of intracellular and membrane progesterone receptor isoforms in the mediobasal hypothalamus during pro-estrus. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01920.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonstein JS, Blaustein JD. Immunocytochemical investigation of nuclear progestin receptor expression within dopaminergic neurones of the female rat brain. J Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:534–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai LM, Shieh KR, Pan JT. Circadian changes of serum prolactin levels and tuberoinfundibular dopaminergic neuron activities in ovariectomized rats treated with or without estrogen: the role of the suprachiasmatic nuclei. Neuroendocrinology. 1994;60:520–526. doi: 10.1159/000126789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani SK. Signaling mechanisms in progesterone-neurotransmitter interactions. Neuroscience. 2006;138:773–781. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell JI, Rosenthal MF, McCabe JT, Harrington CA, Chikaraishi DM, Pfaff DW. Tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA in the neurons of the tuberoinfundibular region and zona incerta examined after gonadal steroid hormone treatment. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3:1426–1433. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-9-1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murai I, Reichlin S, Ben-Jonathan N. The peak phase of the proestrous prolactin surge is blocked by either posterior pituitary lobectomy or antisera to vasoactive intestinal peptide. Endocrinology. 1989;124:1050–1055. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-2-1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neill JD, Freeman ME, Tillson SA. Control of the proestrus surge of prolactin and luteinizing hormone secretion by estrogens in the rat. Endocrinology. 1971;89:1448–1453. doi: 10.1210/endo-89-6-1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualini C, Bojda F, Kerdelhue B. Direct effect of estradiol on the number of dopamine receptors in the anterior pituitary of ovariectomized rats. Endocrinology. 1986;119:2484–2489. doi: 10.1210/endo-119-6-2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualini C, Lenoir V, Abed A, Kerdelhue B. Anterior pituitary dopamine receptors during the rat estrous cycle. A detailed analysis of proestrus changes. Neuroendocrinology. 1984;38:39–44. doi: 10.1159/000123863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson WK, Lumpkin MD, McCann SM. Evidence for a physiological role of oxytocin in the control of prolactin secretion. Endocrinology. 1986;119:554–560. doi: 10.1210/endo-119-2-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sar M. Distribution of progestin-concentrating cells in rat brain: colocalization of [3H]ORG.2058, a synthetic progestin, and antibodies to tyrosine hydroxylase in hypothalamus by combined autoradiography and immunocytochemistry. Endocrinology. 1988;123:1110–1118. doi: 10.1210/endo-123-2-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RE, Wu-Peng XS, Pfaff DW. Regulation and expression of progesterone receptor mRNA isoforms A and B in the male and female rat hypothalamus and pituitary following oestrogen treatment. J Neuroendocrinol. 2002;14:175–183. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1331.2001.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh KR, Pan JT. Sexual differences in the diurnal changes of tuberoinfundibular dopaminergic neuron activity in the rat: role of cholinergic control. Biol Reprod. 1996;54:987–992. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod54.5.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shughrue PJ, Lane MV, Merchenthaler I. Regulation of progesterone receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in the rat medial preoptic nucleus by estrogenic and antiestrogenic compounds: an in situ hybridization study. Endocrinology. 1997;138:5476–5484. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.12.5595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MS, Freeman ME, Neill JD. The control of progesterone secretion during the estrous cycle and early pseudopregnancy in the rat: prolactin, gonadotropin and steroid levels associated with rescue of the corpus luteum of pseudopregnancy. Endocrinology. 1975;96:219–226. doi: 10.1210/endo-96-1-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P. Characteristics of membrane progestin receptor alpha (mPRalpha) and progesterone membrane receptor component 1 (PGMRC1) and their roles in mediating rapid progestin actions. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:292–312. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toska K, Kleppe R, Armstrong CG, Morrice NA, Cohen P, Haavik J. Regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase by stress-activated protein kinases. J Neurochem. 2002;83:775–783. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Porter JC. Hormonal modulation of the quantity and in situ activity of tyrosine hydroxylase in neurites of the median eminence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:9804–9806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen SH, Pan JT. Progesterone advances the diurnal rhythm of tuberoinfundibular dopaminergic neuronal activity and the prolactin surge in ovariectomized, estrogen-primed rats and in intact proestrous rats. Endocrinology. 1998;139:1602–1609. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.4.5901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]