Abstract

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait, and the mutations in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene contributes to the CF syndrome. Although CF is common in Caucasians, it is known to be rare in Asians. Recently, we experienced two cases of CF in Korean children. The patients were girls with chronic productive cough since early infancy. Chest computed tomography showed the diffuse bronchiectasis in both lungs, and their diagnosis was confirmed by the repeated analysis of a quantitative pilocarpine iontophoresis test (QPIT). The sweat chloride concentrations of the first patient were 108.1 mM/L and 96.7 mM/L. The genetic analysis revealed that she was the compound heterozygote of Q1291X and IVS8 T5-M470V. In the second case, the sweat chloride concentrations were 95.0 mM/L and 77.5 mM/L. Although we performed a comprehensive search for the coding regions and exon-intron splicing junctions of CFTR gene, no obvious disease-related mutations were detected in the second case. To our knowledge, this is the first report of CF in Korean children identified by a QPIT and genetic analysis. The possibility of CF should be suspected in those patients with chronic respiratory symptoms even in Korea.

Keywords: Cystic Fibrosis, Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator, Sweat, Child, Korea

INTRODUCTION

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a lethal genetic disorder, which manifests a variety of symptoms such as chronic productive cough, respiratory difficulty, meconium ileus, malabsorption, failure to thrive, infertility, etc. CF is caused by the mutations in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene located on the long arm of chromosome 7, and over 1000 mutations in this gene have been described to date (1). CFTR gene encodes a 1,480 amino acid polypeptide, which functions mainly as a chloride channel in epithelial cells of lung, sinuses, pancreas, liver and reproductive tract. The diagnosis of CF is made by several findings, which include the presence of typical clinical features, a history of CF in a sibling, positive sweat test, identification of CFTR mutations in both alleles and an abnormal nasal potential difference measurement (2).

CF is common in Caucasians, especially in Northern and Central Europeans, with an incidence of 1/2000-1/3000 newborns (3). In contrast, CF occurs rarely in Asian populations, as suggested by the previous data in which the incidence of CF was 1/90,000 in Asian infants in Hawaii (4) and about 1/350,000 in Japanese population (5). Until recently, therefore, sweat test has not been established in Korea due to its low incidence, leading to underdiagnosis of this disease even in suspected cases. Up to now only one case of CF was reported in Korea (6). However, this case was diagnosed by using a similar method described by di Sant'Agnese et al. (7), not by a quantitative pilocarpine iontophoresis sweat test, and the DNA analysis was not performed.

Recently, we experienced two Korean girls with CF identified by a quantitative pilocarpine iontophoresis sweat test and the genetic analysis. We herein present these cases with a review of the literatures.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

A 9 yr-old girl was admitted to Samsung Medical Center due to chronic productive cough and shortness of breath. During the infancy she developed cough and sputum, which was associated with frequent respiratory tract infection. Diarrhea persisted from 1 month of age regardless of the dietary formula and is unresponsive to antibiotics. Diarrhea led to poor weight gain and generalized edema, which necessitates hospitalization twice. Mantoux test performed at 10 months of her age because of chronic cough was positive (15×15 mm). Hence she was treated with anti-tuberculosis regimen for 9 months, but her symptoms did not improve. When she was 2 yr old, clubbing fingers were noticed, and at 5 yr of age, she received ventilator care due to severe respiratory distress. At that time, Pseudomonas aeruginosa was isolated from her sputum. Since then, her respiratory symptoms were waxed and waned, and she had been hospitalized several times.

She was born by vaginal delivery without any perinatal problems. Her birth weight was 2.4 kg, which was small for her gestational age (37 weeks). Vaccination was done as scheduled. She had a 7-yr old younger brother, and family history was unremarkable. Besides chronic productive cough and respiratory difficulty, she complained of the intermittent abdominal pain or chest discomfort. She also presented diarrhea after fat-rich meal. Other symptoms were denied.

On admission, her blood pressure was 104/49 mmHg, heart rate 90 beats/min, respiratory rate 26/min and the body temperature 37℃. Her body weight was 19.1 kg (<3 percentile) and her height was 118 cm (<3 percentile). She had chronic ill-looking appearance and her mentality was alert. Both chest walls expanded symmetrically with mild intercostal retraction. Coarse breathing sound and crackles were heard on both lung fields. The heart beats were regular and murmur was not heard. There was hepatomegaly but the spleen was not palpable. Clubbing fingers were noted with cyanosis. There was no specific finding on neurologic examination.

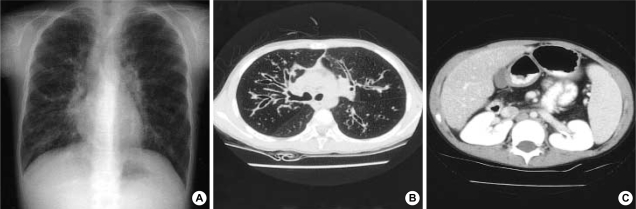

The diseases such as immunodeficiency, allergic disease, congenital heart disease and ciliary dyskinesia were ruled out by her normal complete blood cell count (CBC), serum immunoglobulin levels, specific IgE levels, echocardiogram and bronchial mucosal biopsy. Stool examination showed 30 neutral fat droplets and 60 fatty acid droplets per high power field. Chest and abdomen computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated the bronchiectasis in both lung fields (Fig. 1A, B) and fatty replacement of pancreas with severe atrophy (Fig. 1C). Inflammatory change in maxillary, frontal, ethmoid sinuses and polyposis in the right maxillary sinus were found in CT scan of paranasal sinuses. P. aeruginosa was cultured from her sputum.

Fig. 1.

Radiologic findings of case 1. Plain radiography (A) and computed tomography (CT) scan (B) reveal bronchiectasis. Pancreatic atrophy is found in abdomen CT scan (C).

The sweat chloride concentration was measured by a quantitative pilocarpine iontophoresis sweat test recommended by National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Sweat Testing: Sample Collection and Quantitative Analysis: Approved Guideline. Villnova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997 NCCLS document C34-A.). The test was performed repeatedly on separate days to confirm the diagnosis. The skin of her both forearms was stimulated with pilocarpine and an electrical current of 4 mA for 5 min. The sweat specimens were collected on a gauze pad for 30 min preventing evaporation. The weight of the samples and the chloride concentration was measured according to the mercuriometric titration method (8). The average weights of the sweat samples from both forearms were 131.5 mg in the first test and 134.5 mg in the second test. The average sweat chloride concentrations on both forearms were 108.1 mM/L and 96.7 mM/L in separate occasions performed 2 weeks interval. Intrassay coefficients of variation ranged from 2.8-18.4% for both forearms. Patient's brother showed negative sweat test (25.3 mM/L), while sweat chloride concentration of her mother was 42.6 mM/L. Patient's father did not perform sweat test.

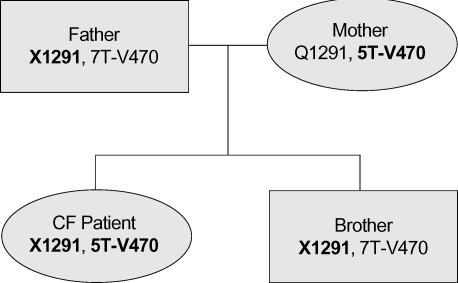

Eleven mutation/polymorphism loci of CFTR gene previously found in a Korean population and ten most common disease-associated loci in Caucasians were screened using SNaP-Shot method as previously detailed (9). In addition, denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and subsequent nucleotide sequencings were performed to find unknown CFTR mutations. Two disease-related mutations were identified in this patient: Q1291X and IVS8 T5-M470V. Haplotyping using the method described by Lee et al. (9) revealed that the two mutations were located in different alleles. Finally, it was identified that Q1291X was from her father and IVS8 T5-M470V was from her mother in the genetic analyses of family members (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Family pedigree of the disease-associated CFTR mutations in case 1. Disease associated genetic variations are shown in bold letters.

Case 2

A 6 yr-old girl was admitted to Samsung Medical Center due to chronic cough, coarse breathing sound and sputum from 2 months of age. She was hospitalized 3 times during the first year of her life because of recurrent bronchiolitis or bronchial asthma. She developed rhinorrhea and nasal stuffiness at 3 yr of age. Additionally she suffered from pneumonia with sinusitis twice, which required hospitalization. At that time, P. aeruginosa was cultured from her sputum and she was treated with intravenous antibiotics. These respiratory symptoms were waxed and waned, and she was transferred for further evaluation.

She was the full-term baby with a birth weight of 3.2 kg. Past medical history revealed that she was sensitized to house dust mite allergen. There was no history of chronic diarrhea, vomiting and failure to thrive. No other symptoms were reported. She had a younger brother, who was 16 months old, and family history was not significant. She was a well-developed girl with weight and height at the 15th percentile for age (17.5 kg, 108.5 cm). Her chest was not retracted, and her breath sounds were slightly coarse with crackles in both lungs. Otherwise, there were no abnormalities on physical examination.

The diagnostic test for her immunologic status including CBC, immunoglobulin level, and complement level demonstrated no abnormality. Chest roentgenogram and CT showed diffuse bronchiectasis in the right middle lobe and both lower lobes. The paranasal sinus CT revealed pansinusitis with polyposis (Fig. 3). There was no abnormality in stool examination and pulmonary function test. P. aeruginosa was isolated from her sputum, and nasal mucosal biopsy failed to provide significant information because the biopsy specimens were not adequate. The sweat test was performed repeatedly on separate days by the same method described in the first case. Sweat samples were collected at the average amount of 177.5 mg and 115.5 mg, respectively. Average sweat chloride concentrations of both forearms were 95.0 mM/L and 77.5 mM/L, which were performed on separate occasions over one-week interval. Intrassay coefficients of variation of sweat chloride of both forearms ranged from 3.8-5.0%. Sweat test was also performed in her parents whose sweat chloride concentrations were below 40 mM/L.

Fig. 3.

CT findings, coronal view in case 2. Pansinusitis with polyposis is shown.

Although we performed a comprehensive search for the coding regions and exon-intron splicing junctions of CFTR gene, no obvious disease-related mutations were found in this case except for some common polymorphisms such as 2694T/G (T854 in exon 14a), which were not supposed to contribute to the disease phenotype (9).

DISCUSSION

Our two patients have manifested chronic productive cough and recurrent pneumonia since their infancy, and P. aeruginosa was isolated from their sputum specimens. These findings are consistent with the previous reports about CF, in which acute or persistent respiratory symptoms are the most common clinical manifestations and P. aeruginosa is the most commonly identified pathogen from the respiratory tract cultures (10). Additionally, chest CT scan revealed the bronchiectasis in both lung fields. Although gastrointestinal symptoms were not apparent in the second patient, in contrast to the first patient, her respiratory symptoms and signs were strongly suggestive of CF. Their diagnosis was confirmed as late as at the age of 9 yr for the first patient and 6 yr for the second patient, although the median age of the diagnosis of CF is 6 months (10). Diagnosis of CF was delayed because reliable sweat test was not available in Korea so far.

Since the sweat electrolytes abnormalities in CF patients were first described by di Sant'Agnese (11), the sweat test is considered as the most valuable diagnostic procedure. Despite its importance in the correct diagnosis of CF, false sweat test results can occur by several factors such as unreliable methods, technical errors of evaporation and contamination, the errors in instrument calibration, and the errors in interpretation (12). Therefore, a quantitative pilocarpine iontophoresis sweat test has been widely used as a reliable standard method, and CF is diagnosed by an increased chloride concentration of more than 60 mM/L on two or more occasions. Our cases were diagnosed by the standardized pilocarpine iontophoresis recommended by NCCLS. Although some laboratories measure sweat sodium concentration, we do not expect additional diagnostic information (13). Many clinical laboratories use chloridometer for the sweat chloride test, and the mercuriometric titration method is only performed in 8% of U.S.A. clinical laboratories, which requires manual procedure (14). The latter can be a good alternative when the chloridometer is not available.

We also performed CFTR mutational analyses which supported the diagnosis. Genetic analysis is a useful diagnostic tool, because the identification of two CFTR mutations is highly specific despite its low sensitivity. A deletion of a single phenylalanine residue at amino acid 508 (ΔF508) is the most prevalent mutation in CF patients from North America (15). The screening of approximately 30 mutations can detect 80-90% CF patients in North America (2). In East Asia only 15 cases has identified CFTR mutations among more than 80 CF patients documented so far (16). Although extensive studies with a large number of CF patients from East Asia are still lacking, the CFTR mutation spectrum seems different between the East Asians and the Caucasians (16, 17). Indeed, a recent analysis of CFTR gene revealed that significant numbers of genetic variations existed in a 192 Korean population, of which sequences are quite different from those of Caucasians (9). Of importance, some of the genetic variations were associated with respiratory and pancreatic diseases. For example, Q1352H mutation showed about 0.9% heterozygote frequencies in the control Korean population and was associated with the chronic bronchiectasis as a haplo-insufficiency form. These results imply that considerable numbers of individuals, which have the homozygote or compound heterozygote genotypes of disease-beating CFTR mutations, will exist in 48 million-sized South Korean population.

In the first case, IVS8 T5-M470V and Q1291X mutations were identified in each allele. IVS T5 variation, which decreased the proper mRNA splicing of CFTR gene, was reported to be highly associated with disease phenotype when joined with the M470V polymorphism (18). Q1291X mutation evokes the deletion of C-terminal 63 amino acids from intact CFTR protein and also was shown to be associated with CF (19). We could not find the disease-associated CFTR mutations in the second case even after extensive analysis of the entire coding regions and the exon-intron splicing junctions. Recently, an interesting result was reported that significant proportions of variant CF do not have CFTR mutations (20). The clinical findings in the second case, a monosymptomatic lung pathology with the defect in sweat chloride concentration, belongs to the category of the variant CF. Rare mutations in deep intron regions or factors other than CFTR mutations may be responsible for the disease phenotypes in the second case.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of CF in Korean children identified by a quantitative pilocarpine iontophoresis sweat test and genetic analysis. Even though the molecular diagnosis is confirmatory and helpful for the carrier detection, it cannot be applied easily to the CF diagnosis because (1) the reported CF mutations are over 1,000, (2) common CF mutations have not been identified in Korean population, and (3) its low cost-effectiveness. Accordingly, the standardized sweat chloride test is recommend for the diagnosis of CF, although 10% of CF cases showed normal values (13, 21).

In conclusion, we experienced two cases of CF. A high index of suspicion is necessary to diagnose CF in patients with chronic respiratory symptoms even in Korea, although the incidence of CF is low.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by grant 02-PJ1-PG3-21499-0003 from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea (M.G.L.).

References

- 1.Cystic Fibrosis Mutation Database. The Cystic Fibrosis Genetic Analysis Consortium. http://www.genet.sickkids.on.ca/cftr.

- 2.Boat TF. Cystic fibrosis. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 17th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004. pp. 1437–1450. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farrell PM. Improving the health of patients with cystic fibrosis through newborn screening. Adv Pediatr. 2000;47:79–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright SW, Morton NE. The incidence of cystic fibrosis in Hawaii. Hawaii Med J. 1968;27:229–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamashiro Y, Shimizu T, Oguchi S, Shioya T, Nagata S, Ohtsuka Y. The estimated incidence of cystic fibrosis in Japan. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;24:544–547. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moon HR, Ko TS, Ko YY, Choi JH, Kim YC. Cystic fibrosis: A case presented with recurrent bronchiolitis in infancy in a Korean male infant. J Korean Med Sci. 1988;3:157–162. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1988.3.4.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.di Sant'Agnese PA, Daring RC, Perera GA, Shea E. Abnormal electrolyte composition of sweat in cystic fibrosis of the pancreas: Clinical significance and relationship to the disease. Pediatrics. 1953;12:549–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schales O, Schales SS. A simple and accurate method for the determination of chloride in biological fluids. J Biol Chem. 1941;140:879–884. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JH, Choi JH, Namkung W, Hanrahan JW, Chang J, Song SY, Park SW, Kim DS, Yoon JH, Suh Y, Jang IJ, Nam JH, Kim SJ, Cho MO, Lee JE, Kim KH, Lee MG. A haplotype-based molecular analysis of CFTR mutations associated with respiratory and pancreatic diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2321–2332. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Patient Registry 1996 annual data report. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.di Sant'Agnese PA, Darling RC, Perera GA, Shea E. Sweat electrolyte disturbances associated with childhood pancreatic disease. Am J Med. 1953;15:777–784. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(53)90169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LeGrys VA. Sweat testing for the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis: Practical considerations. J Pediatr. 1996;129:892–897. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welsh MJ, Ramsey BW, Accurso F, Cutting GR. Cystic fibrosis. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2001. pp. 5136–5139. [Google Scholar]

- 14.LeGrys VA, Burnett RW. Current status of sweat testing in North America. Results of the College of American Pathologists needs assessment survey. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1994;118:865–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemna WK, Feldman GL, Kerem BS, Fernbach SD, Zevkovich EP, O'Brien WE, Riordan JR, Collins FS, Tsui LC, Beaudet AL. Mutation analysis for heterozygote detection and the prenatal diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:291–296. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199002013220503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong LJ, Alper OM, Wang BT, Lee MH, Lo SY. Two novel null mutations in a Taiwanese cystic fibrosis patient and a survey of East Asian CFTR mutations. Am J Med Genet. 2003;120:296–298. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsui LC. The spectrum of cystic fibrosis mutations. Trends Genet. 1992;8:392–398. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90301-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuppens H, Lin W, Jaspers M, Costes B, Teng H, Vankeerberghen A, Jorissen M, Droogmans G, Reynaert I, Goossens M, Nilius B, Cassiman JJ. Polyvariant mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator genes. The polymorphic (TG)m locus explains the partial penetrance of the T5 polymorphism as a disease mutation. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:487–496. doi: 10.1172/JCI639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldmann D, Laroze F, Troadec C, Clement A, Tournier G, Couderc R. A novel nonsense mutation (Q1291X) in exon 20 of CFTR (ABCC7) gene. Hum Mutat. 2001;17:356. doi: 10.1002/humu.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groman JD, Meyer ME, Wilmott RW, Zeitlin PL, Cutting GR. Variant cystic fibrosis phenotypes in the absence of CFTR mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:401–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart B, Zabner J, Shuber AP, Welsh MJ, McCray PB., Jr Normal sweat chloride values do not exclude the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:899–903. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/151.3_Pt_1.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]