Abstract

BioNumbers (http://www.bionumbers.hms.harvard.edu) is a database of key numbers in molecular and cell biology—the quantitative properties of biological systems of interest to computational, systems and molecular cell biologists. Contents of the database range from cell sizes to metabolite concentrations, from reaction rates to generation times, from genome sizes to the number of mitochondria in a cell. While always of importance to biologists, having numbers in hand is becoming increasingly critical for experimenting, modeling, and analyzing biological systems. BioNumbers was motivated by an appreciation of how long it can take to find even the simplest number in the vast biological literature. All numbers are taken directly from a literature source and that reference is provided with the number. BioNumbers is designed to be highly searchable and queries can be performed by keywords or browsed by menus. BioNumbers is a collaborative community platform where registered users can add content and make comments on existing data. All new entries and commentary are curated to maintain high quality. Here we describe the database characteristics and implementation, demonstrate its use, and discuss future directions for its development.

INTRODUCTION

Molecular biologists use numbers from the literature constantly: to plan experiments in the laboratory, to conduct thought experiments, and to construct and evaluate models. The increasing use of computational methods to capture the complexity of biological systems only enhances the importance of having access to such values. Availability of numbers is crucial in transforming our understanding of biological systems from qualitative, schematic arrows models to quantitative predictive models (1). Unfortunately for biologists of all stripes, finding numbers in the vast literature can be an incredibly time consuming and frustrating experience. Even for properties that have been measured numerous times, it can be surprisingly difficult to find the values, or even the order of magnitude. In many cases, it does not necessarily suffice to find a single measurement of this value, as one typically wants to use the most relevant and most accurate measurement of this value that is available in the literature. Different measurements of the same property can be inconsistent, often reflecting subtle differences in the system being studied or the experimental details.

Biology does not have the kind of handbooks that are so common in engineering, physics, and chemistry containing material properties, universal constants, and other numbers of interest and use (2). Efforts to build a repository of quantitative data in molecular biology were made in the 1970s, culminating in the three-volume Biology Data Book (3). Even though it was planned to be updated and expanded regularly, this book has not been continued and is by now effectively obsolete. Like this inspiring predecessor, the BioNumbers database addresses head-on the urgent need to quickly connect researchers with numbers in molecular biology. The literature has expanded enormously since the 1970s. Rather than relying solely on the limited expertise of our group of curators, the BioNumbers database aims to utilize current information technology to capture the knowledge of the research community as a whole. Unlike a handbook, BioNumbers is dynamic, being continuously updated by curators and by engaged members of the scientific community.

THE DATABASE

The inconvenience to a single biologist of having to spend several hours searching textbooks and the Internet for a number may seem of trivial importance. But when integrated over the whole of the biological research community, we would argue that such difficulties have not only slowed progress but have also made molecular biology less quantitative than it perhaps should be. Inspired by such considerations, we have created BioNumbers (http://bionumbers.hms.harvard.edu/), the database of key numbers in molecular and cell biology. The goal of BioNumbers is to quickly connect researchers to numbers available in the literature. Visitors to the site can search the database with text strings or by browsing through menus. Registered users can contribute entries by providing information on values of interest that have been published in a peer reviewed journal. Users can also provide commentary on numbers already in the database. All numbers and commentary are curated to ensure that entries are of a scholarly nature and tone. As all numbers are derived from the literature and are referenced, entries are not a question of personal view but based on evidence, as judged according to the standards of the scientific community.

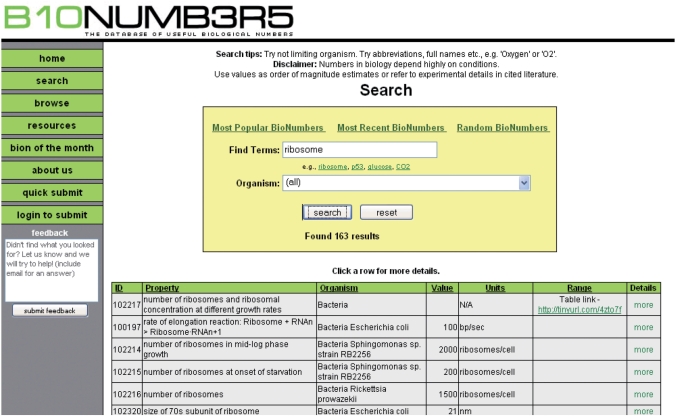

BioNumbers currently contains >4500 distinct properties from >200 organisms. The data were extracted manually from >1000 separate references. Table 1 depicts some of the main statistics of the database. The organisms with the most properties are, in decreasing order: Escherichia coli, Homo sapiens, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Rattus norvegicus, Xenopus laevis, Mus musculus, Spinacia oleracea (spinach), Drosophila melanogaster, and Caenorhabditis elegans. Some properties are derived from less-specific groups, such as biosphere, mammalian cells and plants. The data in BioNumbers are accessible through two different search options: Free Text and Browse. The complete database can also be downloaded as a flat file at: http://bionumbers.hms.harvard.edu/resources.aspx. Each of the >4500 properties in BioNumbers is described by the fields shown in Table 2. Screenshots of the BioNumbers database are presented in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Database vital statistics

| Number of entries | ∼4500 |

| Number of distinct references | ∼1000 |

| Number of organisms | ∼200 |

| Unique visitors per day | ∼150 |

| Searches performed in BioNumbers per month | ∼4000 |

Table 2.

Fields for BioNumbers entries

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| ID | A unique, automatically generated ID for every BioNumber. |

| Property | The property quantitated by the BioNumber. |

| Organism | Can be chosen from a drop down menu consisting >50 organisms. Previously undefined organisms can be entered manually. Special groups are ‘generic’, ‘unspecified’, ‘various’ and ‘biosphere’. |

| Value | The value for the property. |

| Units | Use whatever unit is appropriate and/or standard in the relevant field of study. If no units, then ‘Unitless’. |

| Range | In cases where a range of values is available or an associated standard error or deviation. |

| Reference | The literature reference for the BioNumber. |

| PubMed ID | The ID number of the reference in PubMed. |

| Entered By | The user entering the BioNumber. |

| Primary Source | If the BioNumber was found in a book or review that referenced a primary source, the primary literature source is entered. |

| Primary Source PubMed ID | The ID number of the original primary reference in PubMed. |

| Measurement method | A short description of the method used to obtain the number. |

| Keywords | Words or brief phrases that help describe the BioNumber to aid searches. |

| Comments | Any other pertinent information. |

| Date added | Date BioNumber was first entered. |

| Date edited | Date BioNumber was last updated. |

Figure 1.

Screenshot of the BioNumbers database website showing results for the search term ‘ribosome’.

Two problems bedevil nearly any attempt to quantify a biological property: variability and experimental conditions (e.g. Mg concentration, growth temperature, etc.). Variation is one of the pervasive aspects of biology. Indeed, even within a clonal population of genetically identical cells there can be wide cell-to-cell variability for many parameters. Variability makes the task of ascribing a number to the properties of biological systems fraught with the danger of misinterpretation. In an attempt to account for such variability, BioNumbers records the ranges and/or standard deviations reported for the number in question, whenever available. It is evident to any working scientist that the experimental method used to measure a parameter can greatly influence the measured value. To account for experimental influences on the measured value, BioNumbers records can include experimental details, such as the environmental conditions under which cells were grown or which technique was used to make the measurement. BioNumbers also allows for multiple entries of the same property to accommodate measurement of the same property by different groups or methods. As each record in BioNumbers is directly referenced to a literature source, a researcher can quickly find out how the number was obtained. We feel that any caveats arising from variability and experimental influences are usually far outweighed by the benefit of having an actual number. Indeed, even if a number is only accurate within an order of magnitude, it can provide significant insight.

What qualifies as a good BioNumber, one worth entering into the database? This is hard to define precisely and there is certainly no a priori limit on the size of the database. We anticipate that as researchers engage with the database, by requesting that certain numbers be found by our curators or by adding these numbers themselves, that the database will fill with numbers important to a diversity of specialties in molecular and cell biology. In seeding the database, we have initially focused on model organisms and on extreme cases. For instance, in properties where the value is known for many organisms (e.g. number of chromosomes), we have chosen to create entries for common laboratory organisms and for the extreme cases that describe the limits of that property (e.g. the animals with the most and least chromosomes).

We do not envision BioNumbers as a one-stop destination, but rather as the first stop in the search for biological numbers. In some cases, numbers for specific systems have already been compiled on-line, and BioNumbers does not aim to replace such laudable projects. To the contrary, we aim to connect more researchers to such sites through the use of ‘meta-BioNumbers’ that provide links to already available on-line tables of useful numbers (e.g. the E. coli CyberCell Project, BNID 100599 or the spectra of pigments, BNID 101373). In addition, BioNumbers is not intended to be a storehouse for high-throughput (HTP) data. Not only is HTP data well-serviced by other on-line repositories, such data are also typically of a relative nature, while BioNumbers generally aims to catalog absolute values, usually with measurement units. BioNumbers contains links to HTP repositories via meta-BioNumbers (e.g. BNID 100597, 100598). Thus, the BioNumbers database serves as a portal, directing researchers to numbers in the literature and to Internet resources rich in such numbers.

METHODS

The software is implemented as a Microsoft ASP.NET 2.0 web application with a Microsoft SQL Server 2005 database. The search is performed with built-in SQL commands filtering each field separately and integrating the results (hits) using flexible pre-defined weights to give a final hit list. The data were collected via an extensive and ongoing literature mining effort, as performed by the BioNumbers team and the current community of BioNumbers database users. The database is curated by the BioNumbers team, as well as through the ability of registered users to comment on entries and thus facilitate corrections and provide further details. Every database entry has a unique BioNumber identification number (BNID) that can also be searched. Entries can be updated by the original contributor or by the administrators. Every change is saved as a new version with the database showing the most current version by default but enabling views of older versions. Throughout the article, each time we invoke some particular BioNumber of interest, we reference its BioNumbers ID (e.g. BNID 102345).

Example of use: thought experiments and generating hypotheses using BioNumbers

To show the power and usefulness of BioNumbers we address a specific thought experiment: What limits the maximal rate at which a bacterium can divide? That is, why does E. coli under ideal conditions of LB medium and 37°C divide every ∼20 min (BNID 100260) and not every ∼2 min? Clearly the ability to divide at faster rates would provide an overwhelming selective advantage, at least in laboratory conditions. There are many cellular processes that could potentially limit E. coli to a ∼20 min doubling time. But for most such processes, it seems possible for the bacterium to overcome the limitation by increasing the amount of the limiting factor, for instance by increasing the number of nutrient transporters, the number of DNA replication circles, or the number of RNA polymerase complexes. But ribosomes are an interesting partial exception to this rule. Ribosomes translate all the proteins in the cell including those that are assembled into new ribosomes. Doubling ribosome content would necessitate translating twice the number of ribosomal proteins. Here then is a potentially limiting rate: the time that it takes a ribosome to translate enough amino acids to copy itself (4). We demonstrate the use of the BioNumbers database with a brief analysis of these considerations. An E. coli ribosome contains in total ∼7500 amino acids (7459, Search term: ‘ribosome’, BNID101175) and the translation rate is as high as ∼21 aa/sec (Search term: ‘translation ribosome’, BNID100059). Translating a single copy of all of the ribosomal proteins thus minimally requires ∼7500/21 ≈ 400 sec ≈ 7 min. In order to make a new cell of the same size, each ribosome must make a copy of itself. Taking into account essential translational cofactors like the elongation factors EF-Tu and EF-G would increase the required time to ∼9 min. It therefore seems impossible to obtain a cellular doubling time faster than ∼9 min. Perhaps when further requirements for ribosome duplication are taken into account, it will be evident why E. coli double in ∼20 min. We thus see that with simple calculations and with several useful biological numbers on hand, we can generate an intriguing hypothesis for what sets a lower bound on the proliferation rate of E. coli.

FUTURE PLANS AND CONCLUSIONS

BioNumbers is a dynamic database that is being continuously expanded and advanced. The support of the scientific community, in particular by providing new numbers for addition to the database, will greatly increase its usefulness. To expand on the database functionality of BioNumbers, we are currently developing a ‘BioNumber of the month’ feature which will showcase BioNumbers of special interest by describing how the number was measured and its relevance to different fields of study. A future direction currently being considered is a comparative table builder, in which tables would automatically be generated for users that specify a property and the organisms of interest. These tables could facilitate comparative studies and could lead to new insights into the quantitative design principles of biological systems. Another future direction under consideration is a graphical interface that will visualize the relative scales of entries that share the same units (e.g. velocities, volumes, concentrations). Such a tool would be reminiscent of the well-known displays that visualize the progression in length scale from molecules to galaxies.

Numbers are often peripheral components in contemporary publications, relegated to the supplementary information because they are not central to the ‘narrative’. Therefore, although great efforts are often required to accurately and precisely measure properties in biology, there is generally little reward for such efforts. We therefore envision the creation of a ‘Journal of BioNumbers’ where authors could send short reports on important numbers that they have measured, with details on the method and how it relates to previous measurements. This journal would be peer reviewed and edited to ensure that only numbers, or sets of numbers, truly worthy of addition to the scientific literature were considered.

Numbers are absolute and immutable entities. Biology is built on adaptation, flexibility and variation. It is thus no surprise that concrete values for many biological properties are hard to find. Most quantitative properties in biology depend on the context or the method of measurement, the organism and the cell type. Yet it is clear that characteristic numbers and ranges are very useful tools to have available. Doing biology without knowing the numbers can feel like learning history without knowing geography. BioNumbers is an integrated and practical portal that will provide researchers with a greater ability to do biology by the numbers.

FUNDING

Systems Biology Department at Harvard Medical School, and Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel, to BioNumbers. Funding for open access charge: Personal research funds of corresponding author.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Marc Kirschner, Rebecca Ward and the Systems Biology department at Harvard Medical School for providing a nurturing environment and financial support. They also thank the Information Technology department at Harvard Medical School, Afaq Husain and the Zaztech development team, Yiftach Ravid and the Equivio team, Ricardo Vidal and the OpenWetWare team at MIT, Jaime Prilusky and the bioinformatics unit at the Weizmann Institute of Science, Ruchi Chauhan, Ben Marks, Phil Mongiovi, David Osterbur, Rob Phillips, Chris Sander, and Sudhakaran Prabakaran.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alon U. An Introduction to Systems Biology: Design Principles of Biological Circuits. London: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lide DR. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. 89th edn. Boca Raton FL: CRC press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altman PL, Katz DSD. Biology Data Book. 2nd edn. Bethesda, Maryland: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper S. Bacterial Growth and Division: Biochemistry and Regulation of Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Division Cycles. San Diego, California: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]