Abstract

Secondary lymphoid organs and peripheral tissues are characterized by hypoxic microenvironments, both in the steady state and during inflammation. Although hypoxia regulates T-cell metabolism and survival, very little is known about whether or how hypoxia influences T-cell activation. We stimulated mouse CD4+ T cells in vitro with antibodies directed against the T-cell receptor (CD3) and CD28 under normoxic (20% O2) and hypoxic (1% O2) conditions. Here we report that stimulation under hypoxic conditions augments the secretion of effector CD4+ T-cell cytokines, especially IFN-γ. The enhancing effects of hypoxia on IFN-γ secretion were independent of mouse strain, and were also unaffected using CD4+ T cells from mice lacking one copy of the gene encoding hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Using T cells from IFN-γ receptor–deficient mice and promoter reporter studies in transiently transfected Jurkat T cells, we found that the enhancing effects of hypoxia on IFN-γ expression were not due to effects on IFN-γ consumption or proximal promoter activity. In contrast, deletion of the transcription factor, nuclear erythroid 2 p45–related factor 2 attenuated the enhancing effect of hypoxia on IFN-γ secretion and other cytokines. We conclude that hypoxia is a previously underappreciated modulator of effector cytokine secretion in CD4+ T cells.

Keywords: hypoxia, gene regulation, CD4+ T cells, effector cytokine, IFN-γ

CLINICAL RELEVANCE.

T lymphocytes will be exposed to low ambient oxygen concentrations during recirculation through secondary lymphoid organs and in inflamed tissues. Relatively little is known about the effects of hypoxia on T cells. Our finding, that IFN-γ secretion is particularly enhanced under hypoxic conditions, suggests that the oxygen-rich pulmonary environment may not be as effective as other tissues in supporting maximal IFN-γ secretion in a T cell–autonomous manner.

The ability to sense and respond to changes in oxygen concentration is a fundamental property of all nucleated cells (1). Many tissues are hypoxic in the steady state, and inflammation will further reduce local tissue oxygen concentration due to edema and compromised diffusion of oxygen. Secondary lymphoid organs, including the thymus and spleen, contain hypoxic regions that increase with distance from the arterial blood supply (2). In the case of mouse spleen and lymph nodes, oxygen content was found to average below 5% (3, 4). Thus lymphocytes will be exposed to very low oxygen concentrations in inflamed tissues, as well as during recirculation through secondary lymphoid organs.

Caldwell and colleagues (3) reported that hypoxia enhanced T cell survival, which was recently attributed to the induction of adrenomedullin expression and inhibition of activation-induced cell death (5). Hypoxia also down-regulates T cell Kv1.3 channel expression, and can affect Ca++ signaling (6, 7), although the molecular mechanisms involved in these responses are not well understood. Despite these studies, very little is known about how hypoxia affects T-cell activation.

Exposure to hypoxia results in alterations in cell metabolism and gene expression, which, in many tissues, are mediated by the transcription factor, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1. HIF-1 is a heterodimer comprised of HIF-1α and HIF-1β subunits, members of the basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS domain family (8). The expression and activity of HIF-1α are regulated by O2-dependent hydroxylation. A variety of nonhypoxic stimuli can also activate HIF-1–dependent gene expression, including inflammatory cytokines and growth factors (9–11), and hypoxia-dependent, but HIF-1–independent, pathways of gene expression have also been described (12–14).

We wanted to explore how T-cell activation was affected by hypoxia, with a specific emphasis on cytokine secretion. Here we report that spleen CD4+ T cells isolated from four different mouse strains secrete substantially more IFN-γ under hypoxic (1% O2) than under normoxic (20% O2) conditions in vitro. The enhancing effects of hypoxia, which we also observed for IL-4, appeared to involve post-transcriptional regulation of the IFN-γ gene. Using CD4+ T cells from wild-type (WT) and gene-targeted mice, we found that enhanced IFN-γ secretion under hypoxic conditions was not affected by partial HIF-1α deficiency, but was significantly attenuated in the absence of the redox-sensitive transcription factor, nuclear erythroid 2 p45–related factor 2 (Nrf2).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse Colonies and Maintenance

WT Balb/c, C57BL/6, and IFN-γ receptor knockout (IFN-γR−/−) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). WT and HIF-1α–heterzygous knockout (HIF-1α+/−) mice on C57BL/6 × 129 background were maintained as previously described (15). WT and Nrf2 knockout (Nrf2−/−) mice on the ICR background were provided by Dr. Shyam Biswal (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). Male or female mice between 6 and 10 weeks of age were used in all experiments, which were conducted at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and University of Rochester Medical Center, in compliance with institutional animal care and use committee guidelines.

CD4+ T-Cell Isolation and Stimulation

Spleen CD4+ T cells were obtained from single-cell suspensions using a positive immunomagnetic selection kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Inc., Auburn, CA). Cells were incubated in 48-well plates (1 × 106 in 1 ml of complete medium) that had been precoated overnight with anti-CD3 antibodies (5 μg/ml, clone 145–2C11, Armenian Hamster IgG1κ), to which was added soluble anti-CD28 (5 μg/ml, clone 37.51, Syrian Hamster IgG2), both from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Complete medium consisted of RPMI 1,640 supplemented with 10% vol/vol FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1% vol/vol nonessential amino acids, 1 μg/ml gentamicin sulfate, 100 IU/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, 20 mM Hepes buffer, and 5 × 10−4 M 2-mercaptoethanol (all media supplements from GIBCO/BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). Cells were cultured under hypoxic or normoxic conditions, and were harvested at 24, 48, and 72 hours. Cell viability was analyzed using trypan blue staining and light microscopy, and total protein content was analyzed in whole-cell lysates using a colorimetric assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Hypoxic Cell Culture

T cells were exposed to hypoxia ex vivo using a hypoxia chamber, as previously described (16). Briefly, tissue culture plates were placed in an airtight chamber (Billups-Rothberg, Del Mar, CA) gassed with 1% O2 and 5% CO2, which was then placed into a tissue culture incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Normoxic controls were placed directly into the tissue culture incubator, which was filled with room air supplemented with 5% CO2, resulting in a final ambient oxygen concentration of 20%. The chamber was flushed before beginning exposure and again at 48 hours. Experiments performed using a hand-held oxygen monitor (Model 5,577; Hudson RCI, Durham, NC) confirmed that the chamber was able to sustain the desired level of hypoxia for a minimum of 48 hours.

Cytokine Measurements

Cell-free supernatants were analyzed by ELISA for secretion of the following cytokines using commercially available kits measuring IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-4, TNF-α, and vascular endothelial growth factor, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Samples were diluted as needed to fall within the standard curves, and were analyzed in duplicate.

Quantitative RT-PCR

CD4+ T cells from WT or Nrf2-deficient mice were stimulated for up to 18 hours in 1% O2 versus 20% O2 with immobilized anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 antibodies, and total RNA was isolated using RNA Easy kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RT-PCR was performed with a FirstStrand cDNA Synthesis kit (SuperArray, Gaithersburg, MD). Quantitative gene expression was analyzed in WT T cells using a 96-well RT-PCR array (Mouse T helper [Th] type 1/Th2/Th3 pathway array; SuperArray), and an IQ5 thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Relative gene expression was calculated by using the 2−ΔΔCt method, in which Ct indicates the fractional cycle number where the fluorescent signal reaches detection threshold. Expression of Nrf2 target genes was analyzed by semiquantitative PCR using the following primer pairs: hemeoxygenase (HO)-1 forward, GAG CAG AAC CAG CCT GAA CTA, HO-1 reverse, GGT ACA AGG AAG CCA TCA CCA; glutathione reductase (GR) forward, CAC GAC CAT GAT TCC AGA TG, GR reverse, CAG CAT AGA CGC CTT TGA CA-3′; glutathione cysteine ligase, modifier subunit (GCLm) forward, TGG AGC AGC TGT ATC AGT GG, GCLm reverse, AGA GCA GTT CTT TCG GGT CA; nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced:quinone oxidoreductase forward, TTC TCT GGC CGA TTC AGA GT, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced:quinone oxidoreductase reverse, GGC TGC TTG GAG CAA AAT AG-3′; β-actin forward, GTG GGC CGC TCT AGG CAC CA, β-actin reverse, CGC TTG GCC TTA GGG TTC AGG.

Transient Transfection Assays

A human IFN-γ promoter construct, containing 312 base pairs upstream from the transcription start site, was amplified from genomic DNA using PCR and sequenced to confirm accurate replication. The 312–base pair promoter fragment was cloned in proper orientation upstream of the firefly luciferase gene in the vector, pGL3 (Promega, Madison, WI). WT or dominant-negative (DN) HIF-1α expression vectors were generated as previously described (17). Jurkat T cells were transfected with promoter reporter constructs or expression vectors by electroporation, as previously described (18), and then stimulated under hypoxic or normoxic conditions with 1 μM calcium ionophore A23187 and 40 ng/ml phorbol myristyl acetate (both from Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) for 18 hours, followed by analysis of reporter gene expression using luminometry. Data are expressed as relative light units or relative activity, as indicated in the figure legends.

RESULTS

T-Cell Stimulation under Hypoxic Conditions Differentially Affects Cytokine Secretion

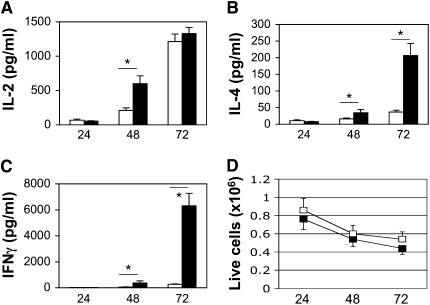

To determine the effects of hypoxia on T-cell cytokine secretion, we isolated spleen CD4+ T cells from 6- to 8-week-old WT female Balb/c mice, and stimulated them with plate-bound anti-CD3 antibodies plus soluble anti-CD28 antibodies under normoxic (20% O2) or hypoxic (1% O2) conditions (see Materials and Methods). Cells were harvested after 24, 48, and 72 hours, and cell-free supernatants analyzed by ELISA. Figure 1 shows that, although the secretion of each cytokine examined increased in a time-dependent manner, the effect of hypoxia was not uniform. IL-2 secretion was increased under hypoxic conditions at 48 hours, but, by 72 hours, there was no significant difference in the amount of IL-2 detected from cells stimulated in 20% versus 1% O2 (Figure 1A). In contrast, CD4+ T cells stimulated in 1% O2 secreted substantially more IL-4 and IFN-γ compared with normoxic controls, especially at the 72-hour time point (Figures 1B and 1C). The relative increase in IFN-γ production under hypoxic conditions was much more pronounced than for IL-4 (24-fold versus 5.7-fold increase). Although the total number of viable cells decreased with time in tissue culture, there was no significant difference in cell viability at any time point when comparing cells stimulated under normoxic and hypoxic conditions (Figure 1D). Total protein content also increased similarly in cells stimulated in 20% versus 1% O2 (1.5-fold versus 1.9-fold increase, respectively; P > 0.05). Thus, these data indicate that CD4+ T cells stimulated under hypoxic conditions secreted significantly more effector cytokines, and that this was not associated with gross perturbations in cell viability or protein synthesis.

Figure 1.

Increased secretion of effector cytokines under hypoxic conditions. CD4+ T cells from wild-type (WT) female Balb/c mice were stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 antibodies under normoxic (20% O2, open bars) or hypoxic (1% O2, closed bars) conditions, as indicated, followed by analysis of cytokine secretion by ELISA (A–C) or cell viability using Trypan blue exclusion (D). Results are the mean (±SEM) of n ≥ 6 mice per time point. *P < 0.05 using Student's t test.

Enhanced IFN-γ Secretion Is Observed in Multiple Mouse Strains

To determine if genetic background influenced the ability of hypoxia to enhance effector cytokine secretion, we next isolated CD4+ T cells from three additional mouse strains, and stimulated them for 72 hours with anti-T cell Receptor (TCR) plus anti-CD28 antibodies, exactly as in Figure 1. Table 1 summarizes the results of these experiments using spleen CD4+ T cells from C57BL/6 and outbred C57BL/6 × 129 and ICR mice (compared with Balb/c mice from Figure 1). Similar to Balb/c CD4+ T cells, there was no significant difference in cell viability after cell stimulation under normoxic versus hypoxic conditions (data not shown). Although the amounts of cytokines detected varied between strains, T cells stimulated under hypoxic conditions secreted significantly greater amounts of IFN-γ and IL-4 compared with normoxic controls (Table 1), and the effect hypoxia was consistently most pronounced for IFN-γ, resulting in 10-fold or greater increases for each strain examined. The effect of hypoxia on IL-2 secretion was strain dependent, with a decrease noted using CD4+ T cells from outbred C57BL/6 × 129 mice versus an approxiamtely twofold increase using CD4+ T cells from ICR mice (Table 1). We repeated cell stimulation experiments using calcium ionophore plus phorbol myristyl acetate to bypass TCR- and CD28-dependent signaling pathways using CD4+ T cells from C57BL/6 × 129 mice, and still observed significant increases in IFN-γ secretion in cells stimulated for 72 hours under hypoxia versus normoxia, although the magnitude of the effect of hypoxia (∼threefold increase) was less than when the T-cell receptor and CD28 were engaged (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

EFFECT OF HYPOXIA ON CYTOKINE GENE EXPRESSION USING T CELLS FROM DIFFERENT MOUSE STRAINS

| IL-2 |

IL-4 |

IFN-γ |

TNF-α |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | 20% O2 | 1% O2 | 20% O2 | 1% O2 | 20% O2 | 1% O2 | 20% O2 | 1% O2 |

| Balb/c | 1212 ± 110 | 1328 ± 91 | 37 ± 5 | 207 ± 36 | 262 ± 41 | 6303 ± 982 | ND | ND |

| C57BL/6 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 28 ± 7 | 696 ± 139 | ND | ND |

| C57BL/6x129 | 1796 ± 134 | 1161 ± 192 | 412 ± 62 | 1155 ± 130 | 31 ± 5 | 339 ± 23 | 209 ± 13 | 419 ± 36 |

| ICR |

413 ± 140 |

916 ± 31 |

33 ± 11 |

215 ± 81 |

405 ± 26 |

6612 ± 2221 |

ND |

ND |

Definition of abbreviation: ND, not done.

All values are in pg/ml using CD4+ T cells (1 × 106/ml) from female mice stimulated for 72 hours with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 antibodies, and are the mean ± SEM of n = 5 (ICR) or n = 6 mice per group.

Hypoxia Does Not Affect T-Cell IFN-γ Consumption

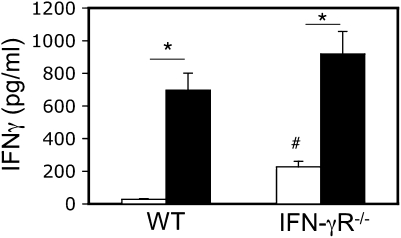

Cytokine concentrations in tissue culture supernatants are determined by the balance between secretion and consumption. Because hypoxia can affect T-cell metabolic rate, it was possible that increased detection of IFN-γ by ELISA in T cells stimulated under hypoxic conditions was due to reduced autocrine consumption of IFN-γ. To address this possibility, we compared spleen CD4+ T cells from WT mice and gene-targeted IFN-γR–deficient (IFN-γR−/−) littermates. If the enhanced detection of IFN-γ under hypoxic conditions was solely due to reduced IFN-γ consumption, then WT T cells stimulated under hypoxic conditions should mimic IFN-γR−/− T cells stimulated under normoxic conditions: Figure 2 shows that this was not the case. Although more IFN-γ was detected from IFN-γR−/− versus WT T cells stimulated in either oxygen concentration, IFN-γR−/− CD4+ T cells still secreted significantly more IFN-γ in 1% O2 versus 20% O2.

Figure 2.

Increased detection of IFN-γ is not due to reduced receptor-mediated consumption. CD4+ T cells from WT and IFN-γ receptor (IFN-γR)−/− littermates on the C57BL/6 background were stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 antibodies for 72 hours under normoxic (20% O2, open bars) or hypoxic (1% O2, closed bars) conditions, and IFN-γ was measured by ELISA. Results are the mean (±SEM) of n = 6 mice per time point. *P < 0.05 for the effect of oxygen concentration; #P < 0.05 for the effect of genotype.

HIF-1α Does Not Mediate the Enhancing Effect of Hypoxia on IFN-γ Gene Expression

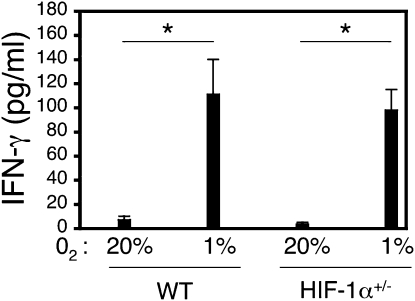

The transcription factor, HIF-1α, is activated by low oxygen tension, and regulates the expression of hundreds of genes involved in metabolic pathways. Homozygous deficiency of HIF-1α in mice results in embryonic lethality due to vascular and other defects (19, 20). Mice that are heterozygous for an Hif1a knockout allele develop normally, but have impaired physiological responses to hypoxia, ischemia, and allergen challenge (15, 21–24). To determine whether partial deficiency of HIF-1α influenced T-cell IFN-γ secretion, we isolated spleen CD4+ T cells from WT mice and HIF-1α–heterozygous (HIF-1α+/−) littermates, and stimulated them as in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 3 shows that CD4+ T cells from both WT and HIF-1α+/− male littermates secreted more IFN-γ under hypoxic than under normoxic conditions, without a significant difference based on genotype. Similar results were obtained using CD4+ T cells isolated from female mice stimulated under hypoxic conditions (data not shown). Secretion of the HIF-1α target gene vascular endothelial growth factor was reduced in CD4+ T cells from HIF-1α+/− mice compared with WT controls stimulated under 20% O2 (13.7 ± 1.4 versus 23 ± 2.1 pg/million cells), but not 1%O2 (56.7 ± 4.3 versus 55.9 ± 5.1 pg/million cells; mean ± SEM; n = 5 each, HIF-1α+/− and WT mice, respectively). Taken together, these data indicate that the effects of hypoxia on T-cell cytokine gene expression are not affected by partial HIF-1α deficiency (see also Discussion).

Figure 3.

Increased secretion of IFN-γ is not affected by partial deficiency of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α. CD4+ T cells from male WT and HIF-1α+/− littermates on the C57BL/6 × 129 background were stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 antibodies for 72 hours under normoxic (20% O2) or hypoxic (1% O2) conditions, as indicated, and IFN-γ was measured by ELISA. Results are the mean (±SEM) of n = 5–6 mice per time point. *P < 0.05 for the effect of oxygen concentration, determined using Student's t test.

Hypoxia Enhances IFN-γ Gene Expression at a Post-Transcriptional Level

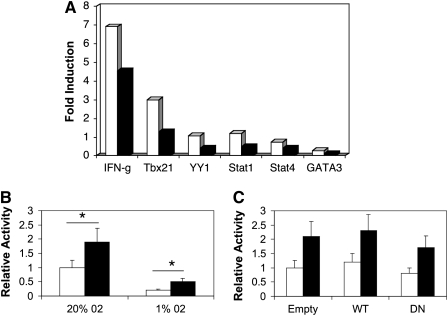

To determine if hypoxia enhanced the rate of IFN-γ gene transcription, we analyzed mRNA from resting control CD4+ T cells and CD4+ T cells stimulated for 18 hours with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 antibodies by quantitative RT-PCR (see Materials and Methods). In these experiments, we found that the expression of IFN-γ, as well as transcription factors implicated in IFN-γ gene expression, including T-bet (Tbx21), Yin-Yang-1 (YY1), Stat1, Stat4, and GATA3, were lower in T cells stimulated under 1% versus 20% O2 (Figure 4A). Similarly, although absolute promoter activity was higher in cells cultured in 20% versus 1% O2 (Figure 4B), the relative inducibility of a proximal IFN-γ promoter construct was not affected by oxygen concentration or cotransfection of WT or DN HIF-1α expression vectors (Figures 4B–4C). Taken together, these data suggest that CD4+ T cells stimulated in hypoxic conditions increase IFN-γ gene expression at a post-transcriptional level.

Figure 4.

Hypoxia does not enhance IFN-γ mRNA expression or promoter activity. (A) Spleen CD4+ T cells from WT mice were stimulated under 20% O2 (open bars) or 1% O2 (closed bars) for 18 hours, followed by analysis of mRNA expression using a quantitative PCR array. The results are expressed as fold induction relative to unstimulated cells (see Materials and Methods), and are from one experiment representative of three. (B) Jurkat T cells were transiently transfected with a luciferase-based proximal IFN-γ promoter construct, and then stimulated for 18 hours under normoxic (20% O2) or hypoxic (1% O2) conditions with calcium ionophore and phorbol myristyl acetate (PMA), followed by analysis of reporter gene activity using luminometry. (C) Cells were cotransfected with WT or dominant negative (DN) HIF-1α expression vectors, and stimulated in 1% O2. (B and C) Open bars, rest; closed bars, iono/PMA. Results are the mean (±SEM) of n ≥ 3 experiments expressed relative to promoter activity in unstimulated T cells. *P < 0.05.

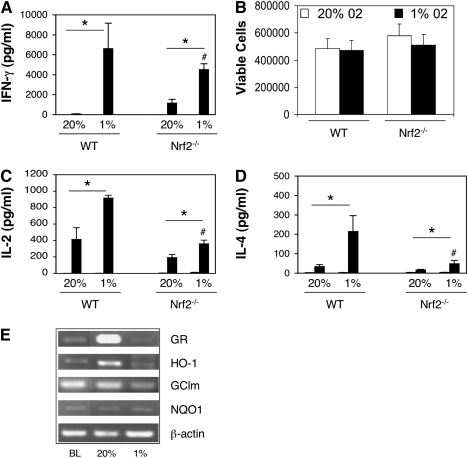

Hypoxia-Dependent Up-Regulation of IFN-γ Secretion Is Partially Dependent on Nrf2

The transcription factor, Nrf2, was recently implicated in the regulation of gene expression in response to the hypoxia-mimetic cobalt chloride, as well as under conditions of hypoxia followed by reoxygenation (12, 13). Nrf2 controls the expression of numerous antioxidant genes, but its role in T-cell activation is not well understood. To determine if Nrf2 was involved in hypoxia-dependent IFN-γ secretion, we compared spleen CD4+ T cells from WT mice and Nrf2−/− littermates activated under hypoxic and normoxic conditions. Figure 5 shows that deficiency of Nrf2 significantly attenuated the ability of hypoxia to augment IFN-γ secretion. This was not associated with significant differences in cell survival, as determined by trypan blue staining (Figure 5B). In addition to IFN-γ secretion, the enhancing effects of hypoxia on IL-2 and IL-4 secretion were also attenuated using Nrf2−/− CD4+ T cells (Figures 5C–5D). To determine how oxygen tension affected Nrf2 activity in T cells, we analyzed the expression of four established Nrf2 target genes using semiquantitative PCR. Interestingly, three out of the four genes examined demonstrated reduced expression under hypoxic conditions, including HO-1, GR, and GCLm (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Increased effector secretion under hypoxic conditions is attenuated by nuclear erythroid 2 p45–related factor 2 (Nrf2) deficiency. CD4+ T cells from WT and Nrf2−/− littermates on the ICR background were stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 antibodies for 72 hours under normoxic (20% O2) or hypoxic (1% O2) conditions, as indicated, and IFN-γ (A), IΛ-2 (C), ανδ IΛ-4 (D) measured by ELISA. (B) Cell viability was analyzed in parallel using Trypan blue staining. Values are the mean (±SEM) of n = 5–6 mice per group. *P < 0.05 for the effect of oxygen concentration; #P < 0.05 for the effect of genotype, determined using the Student's t test. (E) Expression of four Nrf2 target genes was analyzed in WT T cells at baseline (BL) or after stimulation for 4 hours with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 antibodies under 20% or 1% O2, as indicated. Results are representative on n = 3 experiments.

DISCUSSION

Although lymphocytes will be exposed to very low concentrations of oxygen in inflamed tissues and secondary lymphoid organs, the effects of hypoxia on T-cell activation are not well understood. We used an established method to compare CD4+ T-cell activation under normoxic versus hypoxic conditions ex vivo, and made several novel observations. First, we found that CD4+ T-cell stimulation under hypoxic conditions results in enhanced secretion of effector cytokines, including IFN-γ, and that this effect is largely independent of mouse strain or genetic background. The effect of hypoxia did not appear to be simply due to reduced IFN-γ consumption. Second, we found that the effects of hypoxia on IFN-γ secretion were not affected by partial deficiency of HIF-1α, but did depend on the transcription factor, Nrf2. Third, the effects of hypoxia on IFN-γ gene expression appear to involve post-transcriptional regulation.

Previous studies have found that hypoxia can potentiate T-cell survival and affect signal transduction (3, 5–7), but the effects of hypoxia on effector cytokine secretion have not been systematically examined. Using mixed lymphocyte reactions cultured under hypoxic conditions, Caldwell and colleagues (3) reported that 2.5% O2 favored the development of cytotoxic T-cell lytic activity, and that this was associated with reduced detection of IFN-γ in tissue culture supernatants. In contrast, Naldini and colleagues (25) found that hypoxia enhanced IFN-γ (as well as IL-2 and IL-4) secretion in peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated with the mitogen, phytohemagglutinin (PHA). Differences in cell populations (e.g., purified CD4+ T cells) and stimulation conditions (e.g., TCR- and CD28-driven signaling) may explain some of the differences between these and our findings. The fact that we observed a strikingly similar phenotype using CD4+ T cells isolated from four different mouse strains supports the generalizability of our findings, as recently emphasized by Rivera and colleagues (26). In contrast to consistent enhancement of IFN-γ secretion, the effect of cell stimulation under hypoxic conditions on T-cell IL-2 secretion was variable and notably strain-dependent. Whereas IL-2 secretion was enhanced by hypoxia using CD4+ cells from ICR mice, we noted the opposite effect using T cells from C57BL/6 × 129 mice. It will be interesting in future studies to investigate whether modifier genes, or possibly quantitative trait loci, influence T-cell IL-2 production and utilization in an oxygen-dependent manner.

It is difficult to know what true ambient oxygen concentrations are in secondary lymphoid organs or inflamed tissues. Values less than 5% have been detected in the spleen and lymph nodes in the steady state (3, 4), and it seems likely that T cells will be exposed to lower concentrations during clonal expansion in secondary lymphoid organs, and during reactivation in inflamed in tissues. One exception may be the lung, where proximity to ambient oxygen in conducting airways and alveoli will result in higher oxygen content than in other tissues (2). It has been previously noted that immune responses that initiate within the lung tend to favor expansion of IL-4–producing Th2 cells more than IFN-γ–producing Th1 cells (27). The immunologic basis for this is currently not certain, but recent attention has been focused on unique properties of lung antigen-presenting cell subsets (28). Our findings suggest an additional possibility—namely, that the oxygen-rich pulmonary environment may not be as effective as other tissues in supporting maximal IFN-γ secretion in a T cell–autonomous manner.

We acknowledge that we did not define the precise mechanism by which T-cell activation in 1% O2 enhances effector cytokine secretion. In the case of IFN-γ, three observations suggest that this occurs independently of HIF-1α. First, IFN-γ secretion was equally augmented by hypoxia using CD4+ T cells from HIF-1α+/− mice compared with littermate controls (Figure 3). It is formally possible that complete HIF-1α deficiency will have a more dramatic effect, although partial HIF-1α deficiency is sufficient to uncover the critical role of this factor in gene expression in several other models. Second, partial HIF-1α deficiency resulted in higher IFN-γ secretion, especially using CD4+ T cells from female mice stimulated in 20% O2 (24). This result is in keeping with the recent findings of Lukashev and colleagues (29), who reported that the HIF-1.1 isoform suppresses T-cell activation. Reasons for this gender effect are currently not known, but one possibility is that sex hormones influence HIF-1α–dependent gene regulation. Third, we found that oxygen concentration or cotransfection of HIF-1α WT or DN expression vectors did not affect IFN-γ promoter inducibility in Jurkat T cells (Figure 4). Thus, although HIF-1α can inhibit T-cell activation in an animal model of sepsis (30), it appears to be dispensable for the effects of hypoxia reported here.

Our data instead suggest that the effects of hypoxia on T-cell cytokine secretion occur at a post-transcriptional level. Growing evidence points to the importance of post-transcriptional regulation in IFN-γ gene expression, including at the levels of mRNA stability and nuclear transport, and translational regulation (31). Hypoxia and anoxia both induce the unfolded protein and integrated stress responses (32, 33), the latter of which helps explain the dissociation between cytokine mRNA and protein expression that occurs during Th cell differentiation (34). It will be interesting in future studies to determine whether these conserved post-transcriptional mechanisms affect cytokine secretion in hypoxic T cells. Relatively little is known about the role of Nrf2 in T-cell activation or hypoxic responses. Our observations, that exposure of T cells to hypoxia reduced the expression of Nrf2 target genes, and that the enhancing effects of hypoxia on T-cell cytokine secretion were significantly attenuated in the absence of Nrf2, suggest that Nrf2 contributes to cytokine gene expression under these conditions (Figure 5). Similar results were recently reported by Loboda and colleagues (35), who found that the hypoxia mimetic, dimethyloxaloylglycine, inhibited Nrf2 activation in endothelial cells. Nrf2 controls the induction of dozens of antioxidant genes by directly binding to regulatory antioxidant response elements (36), but can also affect cytokine secretion at the post-transcriptional level (37). Future studies investigating the role of Nrf2-dependent signaling pathways in T-cell activation and cytokine gene regulation, and their regulation by ambient oxygen concentration, should be insightful.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Shyam Biswal for providing Nrf2−/− mice used in these studies, Jason Emo for technical assistance, and the Department of Medicine, University of Rochester, for support.

Presented in part at the 2006 American Thoracic Society International Conference (Poster No. A98).

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL073952 (S.N.G.) and R01 HL55338 (G.S.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0139OC on April 16, 2009

Conflict of Interest Statement: S.N.G. has received lecture fees from Merck in 2008 ($1,000–$5,000), a research grant from Sepracor, Inc. ($50,001–$100,000), and a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant for $100,000 or more. L.S. has received an NIH grant for $100,000 or more. None of the other authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Semenza GL. Life with oxygen. Science 2007;318:62–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sitkovsky M, Lukashev D. Regulation of immune cells by local-tissue oxygen tension: HIF1 alpha and adenosine receptors. Nat Rev Immunol 2005;5:712–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caldwell CC, Kojima H, Lukashev D, Armstrong J, Farber M, Apasov SG, Sitkovsky MV. Differential effects of physiologically relevant hypoxic conditions on T lymphocyte development and effector functions. J Immunol 2001;167:6140–6149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang JH, Cardenas-Navia LI, Caldwell CC, Plumb TJ, Radu CG, Rocha PN, Wilder T, Bromberg JS, Cronstein BN, Sitkovsky M, et al. Requirements for T lymphocyte migration in explanted lymph nodes. J Immunol 2007;178:7747–7755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makino Y, Nakamura H, Ikeda E, Ohnuma K, Yamauchi K, Yabe Y, Poellinger L, Okada Y, Morimoto C, Tanaka H. Hypoxia-inducible factor regulates survival of antigen receptor-driven T cells. J Immunol 2003;171:6534–6540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conforti L, Petrovic M, Mohammad D, Lee S, Ma Q, Barone S, Filipovich AH. Hypoxia regulates expression and activity of Kv1.3 channels in T lymphocytes: a possible role in T cell proliferation. J Immunol 2003;170:695–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robbins JR, Molleran Lee SM, Filipovich AH, Szigligeti P, Neumeier L, Petrovic M, Conforti L. Hypoxia modulates early events in T cell receptor-mediated activation in human T lymphopcytes via Kv1.3 channels. J Physiol 2005;564(Pt 1):131–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) pathway. Sci STKE [serial on the Internet]. 2007 [accessed 1 April 2008];2007(407):cm8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Richard DE, Berra E, Pouyssegur J. Nonhypoxic pathway mediates the induction of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 2000;275:26765–26771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips RJ, Mestas J, Gharaee-Kermani M, Burdick MD, Sica A, Belperio JA, Keane MP, Strieter RM. Epidermal growth factor and hypoxia-induced expression of CXC chemokine receptor 4 on non–small cell lung cancer cells is regulated by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PTEN/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway and activation of hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha. J Biol Chem 2005;280:22473–22481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMahon S, Charbonneau M, Grandmont S, Richard DE, Dubois CM. Transforming growth factor beta1 induces hypoxia-inducible factor-1 stabilization through selective inhibition of PHD2 expression. J Biol Chem 2006;281:24171–24181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong P, Hu B, Stewart D, Ellerbe M, Figueroa YG, Blank V, Beckman BS, Alam J. Cobalt induces heme oxygenase-1 expression by a hypoxia-inducible factor–independent mechanism in Chinese hamster ovary cells: regulation by Nrf2 and MafG transcription factors. J Biol Chem 2001;276:27018–27025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim YJ, Ahn JY, Liang P, Ip C, Zhang Y, Park YM. Human prx1 gene is a target of Nrf2 and is up-regulated by hypoxia/reoxygenation: implication to tumor biology. Cancer Res 2007;67:546–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arany Z, Foo SY, Ma Y, Ruas JL, Bommi-Reddy A, Girnun G, Cooper M, Laznik D, Chinsomboon J, Rangwala SM, et al. HIF-independent regulation of VEGF and angiogenesis by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha. Nature 2008;451:1008–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu AY, Shimoda LA, Iyer NV, Huso DL, Sun X, McWilliams R, Beaty T, Sham JS, Wiener CM, Sylvester JT, et al. Impaired physiological responses to chronic hypoxia in mice partially deficient for hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. J Clin Invest 1999;103:691–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitman EM, Pisarcik S, Luke T, Fallon M, Wang J, Sylvester JT, Semenza GL, Shimoda LA. Endothelin-1 mediates hypoxia-induced inhibition of voltage-gated K+ channel expression in pulmonary arterial myocytes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008;294:L309–L318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okuyama H, Krishnamachary B, Zhou YF, Nagasawa H, Bosch-Marce M, Semenza GL. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 in bone marrow–derived mesenchymal cells is dependent on hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem 2006;281:15554–15563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo J, Casolaro V, Seto E, Yang WM, Chang C, Seminario MC, Keen J, Georas SN. Yin-Yang 1 activates interleukin-4 gene expression in T cells. J Biol Chem 2001;276:48871–48878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iyer NV, Kotch LE, Agani F, Leung SW, Laughner E, Wenger RH, Gassmann M, Gearhart JD, Lawler AM, Yu AY, et al. Cellular and developmental control of O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Genes Dev 1998;12:149–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotch LE, Iyer NV, Laughner E, Semenza GL. Defective vascularization of HIF-1alpha–null embryos is not associated with VEGF deficiency but with mesenchymal cell death. Dev Biol 1999;209:254–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kline DD, Peng YJ, Manalo DJ, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Defective carotid body function and impaired ventilatory responses to chronic hypoxia in mice partially deficient for hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002;99:821–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimoda LA, Manalo DJ, Sham JS, Semenza GL, Sylvester JT. Partial HIF-1alpha deficiency impairs pulmonary arterial myocyte electrophysiological responses to hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2001;281:L202–L208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Bosch-Marce M, Nanayakkara A, Savransky V, Fried SK, Semenza GL, Polotsky VY. Altered metabolic responses to intermittent hypoxia in mice with partial deficiency of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Physiol Genomics 2006;25:450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo J, Lu W, Shimoda LA, Semenza GL, Georas SN. Enhanced interferon-gamma gene expression in T cells and reduced ovalbumin-dependent lung eosinophilia in hypoxia-inducible factor-1-alpha–deficient mice. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2009;149:98–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naldini A, Carraro F, Silvestri S, Bocci V. Hypoxia affects cytokine production and proliferative responses by human peripheral mononuclear cells. J Cell Physiol 1997;173:335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rivera J, Tessarollo L. Genetic background and the dilemma of translating mouse studies to humans. Immunity 2008;28:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stumbles PA, Thomas JA, Pimm CL, Lee PT, Venaille TJ, Proksch S, Holt PG. Resting respiratory tract dendritic cells preferentially stimulate T helper cell type 2 (Th2) responses and require obligatory cytokine signals for induction of Th1 immunity. J Exp Med 1998;188:2019–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holt PG, Strickland DH, Wikstrom ME, Jahnsen FL. Regulation of immunological homeostasis in the respiratory tract. Nat Rev Immunol 2008;8:142–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lukashev D, Caldwell C, Ohta A, Chen P, Sitkovsky M. Differential regulation of two alternatively spliced isoforms of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha in activated T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem 2001;276:48754–48763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thiel M, Caldwell CC, Kreth S, Kuboki S, Chen P, Smith P, Ohta A, Lentsch AB, Lukashev D, Sitkovsky MV. Targeted deletion of HIF-1alpha gene in T cells prevents their inhibition in hypoxic inflamed tissues and improves septic mice survival. PLoS One 2007;2:e853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young HA, Bream JH. IFN-gamma: recent advances in understanding regulation of expression, biological functions, and clinical applications. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2007;316:97–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rzymski T, Harris AL. The unfolded protein response and integrated stress response to anoxia. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:2537–2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson LL, Mao X, Scott BA, Crowder CM. Survival from hypoxia in C. elegans by inactivation of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Science 2009;323:630–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheu S, Stetson DB, Reinhardt RL, Leber JH, Mohrs M, Locksley RM. Activation of the integrated stress response during T helper cell differentiation. Nat Immunol 2006;7:644–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loboda A, Stachurska A, Florczyk U, Rudnicka D, Jazwa A, Wegrzyn J, Kozakowska M, Stalinska K, Poellinger L, Levonen AL, et al. HIF-1 induction attenuates Nrf2-dependent IL-8 production in human endothelial cells. Antioxid Redox Signal 2009;11:1501–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobayashi M, Yamamoto M. Molecular mechanisms activating the Nrf2–Keap1 pathway of antioxidant gene regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal 2005;7:385–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang X, Chen X, Song H, Chen HZ, Rovin BH. Activation of the Nrf2/antioxidant response pathway increases IL-8 expression. Eur J Immunol 2005;35:3258–3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]