Abstract

Background. Achieving normohydration remains a non-trivial issue in haemodialysis therapy. Guiding the haemodialysis patient on the path between fluid overload and dehydration should be the clinical target, although it can be difficult to achieve this target in practice. Objective and clinically applicable methods for the determination of the normohydration status on an individual basis are needed to help in the identification of an appropriate target weight.

Methods. The aim of this prospective trial was to guide the patient population of a complete dialysis centre towards normohydration over the course of approximately 1 year. Fluid status was assessed frequently (at least monthly) in haemodialysis patients (n = 52) with the body composition monitor (BCM), which is based on whole body bioimpedance spectroscopy. The BCM provides the clinician with an objective target for normohydration. The patient population was divided into three groups: the hyperhydrated group (relative fluid overload >15% of extracellular water (ECW); n = 13; Group A), the adverse event group (patients with more than two adverse events in the last 4 weeks; n = 12; Group B) and the remaining patients (n = 27; Group C).

Results. In the hyperhydrated group (Group A), fluid overload was reduced by 2.0 L (P < 0.001) without increasing the occurrence of intradialytic adverse events. This resulted in a reduction in systolic blood pressure of 25 mmHg (P = 0.012). Additionally, a 35% reduction in antihypertensive medication (P = 0.031) was achieved. In the adverse event group (Group B), the fluid status was increased by 1.3 L (P = 0.004) resulting in a 73% reduction in intradialytic adverse events (P < 0.001) without significantly increasing the blood pressure.

Conclusion. The BCM provides an objective assessment of normohydration that is clinically applicable. Guiding the patients towards this target of normohydration leads to better control of hypertension in hyperhydrated patients, less intradialytic adverse events and improved cardiac function.

Keywords: adverse event, bioimpedance spectroscopy, fluid overload, hypertension, normohydration

Introduction

Adequate fluid management plays an important role in the treatment of haemodialysis patients. It is well accepted that chronic fluid overload causes left ventricular hypertrophy [1], while, conversely, dehydration is linked to the occurrence of intradialytic adverse events [2]. Both fluid overload and dehydration are linked to an increased morbidity in haemodialysis patients. Guiding the patient along the narrow path between the deleterious effects of fluid overload and dehydration [3,4] can be difficult. However, the availability of a target provided by a practical clinical method could help in the navigation of the patient along this path [5]. As fluid overload and dehydration both influence the extracellular water, this target should be based on the concept of an individual normal extracellular volume (normohydration).

Several studies report the improvement of fluid status and outcome when switching haemodialysis patients to a different dialysis modality such as long or daily dialysis [6,7] or when introducing a low-salt diet [8]. It has been shown previously that patients suffering from hyperhydration of >15% of ECW are prone to a significantly increased mortality risk [9]. Despite these findings, no data so far have demonstrated the possible improvement of a prevalent patient population when introducing the target of normohydration for volume therapy.

In this study, a new bioimpedance spectroscopy device for body composition measurement was used to determine the normohydration weight. The body composition monitor (BCM) provides an objective target for the normal volume status (normohydration weight) in an individual patient without the need for a reference population. Normohydration weight was used together with conventional clinical methods to determine fluid overload of all patients in one dialysis centre and to adjust the patients’ fluid status if necessary. The aim was to reduce fluid overload in hyperhydrated patients whilst minimizing the frequency of intradialytic adverse events.

Methods

Patients

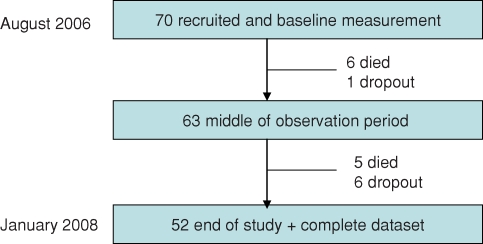

Using the available patient population of one dialysis centre in the Czech Republic, a total of 70 patients were included in the study. These patients represented the complete patient population of the respective centre in August 2006 and additionally all patients starting renal replacement therapy between the 1 August 2006 and the 1 August 2007. Patients with pacemakers or large metallic implants were excluded from the study because of possible adverse effects with the bioimpedance spectroscopy measurement. Eleven patients died in the study period, whereof 3 died within the first 6 month after starting the renal replacement therapy. Seven patients had to be censored because they were transplanted or left the centre. Only patients that covered the complete study period (n = 52) were included in the analysis. Table 1 shows that there is no significant difference in terms of systolic blood pressure and fluid status between the study analysis group and the excluded/deceased patients. Figure 1 presents the patient flow through the study. In total the 52 patients were monitored during an observation period of 400 ± 134 days with 569 BCM measurements. All patients had given informed consent, and the study was approved by the local ethical committee. The achieved treatment time was 5 h and high-flux membranes were used throughout with 90% of patients receiving convective treatments and 6.2% being dialysed by a catheter.

Fig. 1.

Flow of patients through the study.

Determination of normohydration/achieving normohydration

The BCM (Fresenius Medical Care) was used to determine the fluid overload and the weight representing normohydration on the basis of a whole-body bioimpedance spectroscopy measurement [10]. The resistance and reactance were measured by the BCM at 50 discrete frequencies covering the frequency spectrum from 5 to 1000 kHz. The extracellular and the intracellular resistance were obtained on the basis of a Cole model [11,12]. Using these resistances, the extracellular and intracellular fluid volumes and total body water were calculated from a fluid model [13]. These fluid volumes were then used to determine the body composition in terms of fluid overload, normally hydrated lean tissue and normally hydrated adipose tissue [14].

It has been shown elsewhere that the spectroscopy measurement technique has high reproducibility [15–17] and specificity [18]. Extensive validation of the fluid volumes and body composition has been performed against reference methods involving healthy volunteers and patients [13,19,20]. The determination of fluid overload was validated using expert clinical assessment [21] and reduction in fluid status by ultrafiltration [22].

Table 1.

Comparison of the population used for the primary analysis and the excluded/deceased patients

| All patients in primary | Excluded—deceased | |

|---|---|---|

| analysis (initial) | patients (initial) | |

| N | 52 | 11 |

| BPsys_pre [mmHg] | 153 ± 24 | 145 ± 22 |

| BPdia_pre [mmHg] | 82 ± 13 | 65 ± 17 p < 0.05 |

| FOpre/ECW [%] | 8.6 ± 9.3 | 9.1 ± 9.2 |

| FOpost/ECW [%] | −6.3 ± 14 | −7.9 ± 16.9 |

In this study, BCM measurements were performed after a short dialysis interval pre-dialysis with the patient in a supine position directly before the dialysis treatment. The electrodes were fixed to the hand and foot on one side of the body. Patients rested for 5 min before performing the BCM measurement. All nurses in the centre were trained to use the BCM. If any erroneous measurements were detected by the BCM on the basis of a measurement quality indicator, the respective measurement was repeated by the nurse. The post-fluid status was assessed by subtracting the intradialytic weight loss from the fluid overload of the pre-dialysis measurement. The time-averaged fluid overload (TAFO) was calculated as the mean between the pre-dialysis and the post-dialysis fluid status, thus assuming a linear accumulation of fluid in the interdialytic period.

In addition to the fluid overload measurement by the BCM, the patients’ fluid status was assessed clinically, taking into account the blood pressure and signs and symptoms of hypo- and hypervolaemia. Where available the patients’ annual echocardiographic measurement was used in the overall assessment (92% of patients).

End-points of the study

The primary end-point sought was to achieve normohydration in the whole study population. In the pre-dialysis state, a maximal relative fluid overload (fluid overload relative to the extracellular water) of FO/ECW <15% was allowed—this is comparable to an absolute fluid overload of 2.5 L (in the population average). A relative fluid overload between −6% and 6% (resp. −1.1 L and 1.1 L—in the population average) [23] post-dialysis was the secondary end-point desired.

Post-weight reduction was performed in steps <0.5 kg/week (<0.7% of dry weight), and the antihypertensive medication was revised in parallel with changes in fluid status. The patients were measured with the BCM once per month if flesh weight was considered stable—in unstable phases the patients were measured on a weekly basis.

Clinical information

The number of antihypertensive agents prescribed at the time of the BCM measurement was recorded for analysis, and agents prescribed for cardioprotective reasons were not included. Over the course of the study, the administration of erythropoietin was changed from subcutaneous to intra–vascular, and the erythropoietin type was changed from Eprex to Aranesp. As a discussion is ongoing about the conversion factor between Eprex and Aranesp, the haemoglobin data and the erythropoietin data were not included in the analysis.

The blood pressure was measured following the proposals by Agarwal [24]. To improve the reproducibility of the blood pressure measurement, the recordings of six previous dialysis sessions were averaged.

The intradialytic adverse events were collected for the interval of 12 haemodialysis treatments prior to the day of the respective BCM measurement of fluid status. All adverse events were recorded that made an intervention of the nursing staff necessary e.g. symptomatic hypotension and cramps.

Albumin concentration was obtained from the most recent monthly blood chemistry data prior to a BCM measurement. Additionally, eKt/V was calculated using the Daugirdas formula [25]. The residual renal function (RRF) was analysed on the basis of the routinely performed monthly measurement. The ejection fraction was assessed before the initial and after the last fluid status measurement by an experienced echocardiographer—this data was available for 92% of the patients.

Data analysis

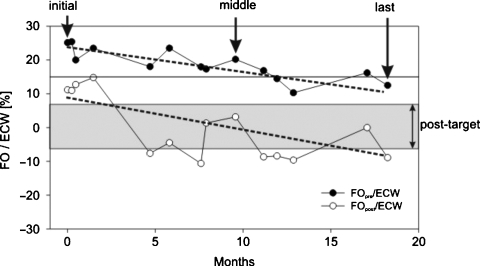

A period of at least 6 months was allowed for a correction of the fluid status and to ensure the cardiovascular stability of the patients. In addition to initial and last measurements, the BCM measurement occurring in the middle of the observation period was chosen allowing the observation period to be analysed as two observation phases, as seen in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Example of reduction in fluid overload in a single patient from Group A (hyperhydrated) over 18 months. The relative fluid overload is shown pre- and post-treatment and the two dotted lines indicate the trend of the fluid reduction. The fluid status pre-treatment (FOpre/ECW) is reduced from 25% (4.9 L) to 20% (4 L) and finally to 12% (2.2 L). Over the same time interval, the fluid status at the end of the treatment (FOpost/ECW) was reduced from 11% (1.9 L) to 3.3% (0.5 L) and finally to −8.9% (−1.1 L).

The changes in hydration status, blood pressure, body composition, heart status, blood chemistry data and symptoms were analysed and the following groups were identified retrospectively on the basis of the initial assessment:

Group All: all patients available for primary analysis (n = 52);

Group A: hyperhydrated patients: 25% of all patients (n = 13) with a fluid overload; FOpre/ECW>15% in the initial assessment;

Group B: adverse event patients: 23% of all patients (n = 12) presenting more than two adverse events in the 4 weeks prior to the initial BCM measurement;

Group C: patients neither in Group A (hyperhydrated) nor in Group B (adverse event) (n = 27).

Statistics

The analysis followed the per protocol analysis, thus the censored patients were not included in the analysis. To analyse the changes induced by the intervention, a pairwise multiple comparison procedure, following Dum's or Holm-Sidak's method, was performed.

The significance of the changes between the initial, the mid and the last measurement in each group and the differences between Groups A, B and C were analysed. The level of significance was set to P = 0.05.

Results

Comparison between the groups

In the initial measurement, the blood pressure at the end of the treatment was significantly higher in Group A compared to Group B (P = 0.028). In contrast, the ejection fraction (P = 0.024) was significantly lower in Group A compared to the other two groups. The absolute fluid overload and the relative fluid overload (FO and FO/ECW) were significantly higher in Group A (hyperhydrated) both at the start and at the end of the treatment (P < 0.001). Patients in Group B presented more adverse events than those in the other two groups (P = 0.024). In addition, the intradialytic blood pressure change was significantly greater in Group B (P = 0.004). At the time of the last measurement, the systolic blood pressure post-dialysis was found to be highest in Group B (P = 0.026). No other significant differences were observed. The number of patients achieving the defined target for the pre- and post-dialytic fluid overload, increased by 66% (n = 12 at the start, n = 25 in the mid and n = 20 at the end of the study).

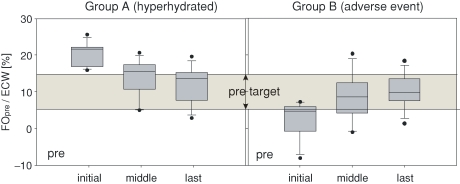

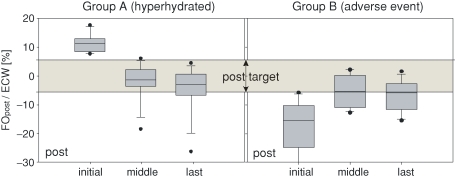

Changes in Group A from the initial to the last measurement

Figure 2 shows the change in fluid overload in one exemplary patient. Figures 3 and 4 and Table 2 indicate the fluid status changes in the various patient groups. In Group A, the fluid overload was reduced significantly in the study period (P < 0.001). A significant reduction in the systolic (P = 0.029) and diastolic (P = 0.042) blood pressure before and after the treatment could be observed in Group A together with a reduction of the antihypertensive medication (P = 0.031). The patients in Group A exhibited an increase in the ejection fraction from 51.8 ± 9.8% to 58.4 ± 8% (P = 0.021).

Fig. 3.

Fluid status changes in Group A (hyperhydrated. left) and Group B (adverse event. right). In these groups, the relative fluid status before dialysis treatment is shown. Each box summarizes the results of the initial, the middle and the last measurements. Additionally, the target range for the relative fluid overload before dialysis treatment (between 6% and 15%) is indicated. The boundaries of the boxes are the 25th and the 75th percentile. The whiskers show the 10th and the 90th percentile, while the dots show outliers (5th and 95th percentiles).

Fig. 4.

Fluid status changes in Group A (hyperhydrated, left panel) and Group B (adverse event, right panel) after dialysis treatment including the target range for the relative fluid overload after treatment (−6% to +6%). The boxes show the results of the initial, the middle and the last measurements.

Table 2.

Comparison of the whole population and the subgroup analysis shown as the mean and the standard deviation

| Group All | Group A (hyperhydrated) | Group B (adverse events) | Group C (not A, not B) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 52 | 13 = 25% of population | 12 = 23% of population | 27 = 52% of population | ||||||||

| Months since the start of RRT | 33.7 ± 51 | 36.8 ± 79 | 47.3 ± 44 | 21.7 ± 28 | ||||||||

| Diabetics | 29% | 43% | 41% | 21% | ||||||||

| Initial | Mid | Last | Initial | Mid | Last | Initial | Mid | Last | Initial | Mid | Last | |

| Age (years) | 61.7 ± 12.5 | 62.3 ± 12.5 | 62.8 ± 12.5 | 60.1 ± 11.1 | 60.5 ± 11.0 | 61.0 ± 11.0 | 58.3 ± 13.5 | 58.9 ± 13.5 | 59.5 ± 13.5 | 63.7 ± 12.7 | 64.3 ± 12.8 | 64.9 ± 12.8 |

| Observation months | 0 | 6.8 ± 3.1 | 13.2 ± 4.7 | 0 | 5.5 ± 3.1 | 11.0 ± 4.9 | 0 | 7.8 ± 3.2 | 14.6 ± 4.6 | 0 | 6.9 ± 3.0 | 13.8 ± 4.5 |

| RRF (ml/24 h) | 596 ± 700 | 376 ± 540° | 337 ± 613+ | 837 ± 778 | 509 ± 625 | 467 ± 594 | 304 ± 530 | 109 ± 192 | 104 ± 245+ | 555 ± 665 | 441 ± 582 | 500 ± 708 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.7 ± 5.9 | 26.8 ± 5.9 | 26.9 ± 5.8 | 24.7 ± 4.5 | 24.3 ± 4.1 | 24.4 ± 4.0 | 27.5 ± 7.7 | 28.2 ± 8.2 | 28.7 ± 8.0 | 27.2 ± 5.6 | 27.3 ± 5.4 | 27.3 ± 5.2 |

| Weight (kg) | 75.7 ± 16.6 | 75.8 ± 16.4 | 76.2 ± 16.7 | 76.5 ± 15.0 | 75.4 ± 13.6 | 75.5 ± 13.1 | 77.0 ± 20 | 79.0 ± 21.8 | 80.6 ± 22.0 | 74.5 ± 16.4 | 74.7 ± 15.6 | 74.8 ± 15.8 |

| BPsys pre (mmHg) | 153 ± 24 | 138 ± 27 | 148 ± 25 | 153 ± 14 | 139 ± 38 | 128 ± 24+ | 155 ± 27 | 144 ± 24 | 159 ± 19 | 150 ± 27 | 140 ± 23 | 149 ± 22 |

| BPdia pre (mmHg) | 82 ± 13 | 71 ± 11 | 72 ± 16 | 87 ± 11 | 74 ± 11 | 67 ± 18+ | 82 ± 15 | 72.6 ± 9 | 77 ± 9 | 80 ± 12 | 70 ± 12o | 70 ± 13+ |

| BPsys post (mmHg) | 145 ± 31 | 138 ± 25 | 138 ± 29 | 158 ± 27 | 131 ± 25o | 128 ± 25+ | 124 ± 24 | 144 ± 24 | 145 ± 32 | 146 ± 32 | 136 ± 26 | 137 ± 27 |

| BPdia post (mmHg) | 77 ± 16 | 71 ± 12 | 66 ± 13 | 84 ± 15 | 72 ± 12o | 64 ± 15++ | 75 ± 16 | 74 ± 6 | 70 ± 12 | 74 ± 15 | 71.3 ± 14 | 65 ± 13+ |

| Antihypertensive medication | 1.0 ± 1.2 | 0.7 ± 1.0 | 0.5 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 1.5 | 1.3 ± 1.4 | 1.1 ± 1.3+ | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.6 ± 1.0 | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 1.0 | 0.4 ± 0.6 | 0.4 ± 0.6 |

| Intradialytic weight loss (% of weight) | 3.2 ± 1.4 | 3.0 ± 1.1 | 3.4 ± 1.3 | 2.6 ± 1.5 | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 3.8 ± 1.4 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 2.9 ± 1.3 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 3.2 ± 1.4 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 3.2 ± 1.3 |

| eKt/V | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 1.72 ± 0.4 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 36.7 ± 3.4 | 36.8 ± 3 | 37.7 ± 2.8 | 35.7 ± 3.5 | 37.9 ± 2.2 | 37.7 ± 3.7 | 37.6 ± 2.7 | 36.8 ± 2.2 | 37.6 ± 1.6 | 36.8 ± 3 | 36.5 ± 3.4 | 38.2 ± 2.2 |

| Adverse events (% of treatments) | 6.7 ± 11.8 | 3.9 ± 10.7 | 3.7 ± 6.7 | 2.1 ± 5.2 | 2.3 ± 5.4 | 1.4 ± 3.2 | 25.7 ± 10 | 3.5 ± 6.6oo | 6.9 ± 7.8++ | 2.1 ± 4.4 | 5.3 ± 14 | 3.2 ± 6.5 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 57.7 ± 8.0 | NA | 59.5 ± 6.5 | 51.8 ± 9.8 | NA | 58.4 ± 8.0+ | 60.4 ± 7.2 | NA | 61.2 ± 6.3 | 59.3 ± 6.4 | NA | 59.3 ± 6.5 |

| Extracellular water (ECW) (L) | 17.5 ± 3.5 | 17.3 ± 3.2 | 17.3 ± 3.2 | 20.4 ± 3.0 | 18.4 ± 2.6oo | 17.9 ± 2.0++ | 16.2 ± 3.3 | 17.1 ± 3.7 | 17.6 ± 3.9 | 16.6 ± 3.1 | 16.9 ± 3.2 | 17.05 ± 3.3 |

| Total body water (TBW) (L) | 36.0 ± 6.7 | 35.2 ± 6.5 | 35.2 ± 6.6 | 40.4 ± 5.8 | 37.5 ± 5.8oo | 36.8 ± 4.7++ | 34.4 ± 7.1 | 34.8 ± 7.5 | 35.2 ± 8.1 | 34.5 ± 6.3 | 34.5 ± 6.4 | 34.6 ± 6.8 |

| Time-averaged fluid overload TAFO (L) | 0.2 ± 1.9 | 0.6 ± 1.1 | 0.4 ± 1.1 | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.9oo | 0.7 ± 1.0++ | −1.0 ± 0.9 | 0.3 ± 0.8oo | 0.4 ± 0.6++ | −0.1 ± 1.3 | 0.5 ± 1.2 | 0.4 ± 1.2 |

| Fluid overload pre FOpre (L) | 1.6 ± 1.8 | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 1.7 ± 1.1 | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 0.9oo | 2 ± 0.9++ | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 1.0o | 1.7 ± 0.8+ | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 1.6 ± 1.3+ |

| Fluid overload post FOpost (L) | −0.7 ± 2.0 | −0.5 ± 1.0 | −0.8 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | −0.44 ± 0.8oo | −0.7 ± 1.3++ | −2.3 ± 1.2 | −0.8 ± 0.8oo | −1 ± 0.7++ | −1.3 ± 1.4 | −0.4 ± 1.2o | −0.7 ± 1.3 |

| FOpre/ECW (%) | 8.6 ± 9.3 | 9.6 ± 6.9 | 9.9 ± 6.1 | 19.7 ± 3.1 | 12.8 ± 5 | 11.5 ± 5.2++ | 2.6 ± 4.9 | 8.3 ± 6.2oo | 10.1 ± 4.4++ | 5.8 ± 8.3 | 8.6 ± 7.6 | 9.2 ± 7.2 |

| FOpost/ECW (%) | −6.3 ± 14.0 | −3.7 ± 7.5 | −5.6 ± 8.2 | 11.2 ± 3.2 | −3.7 ± 5.9oo | −5.0 ± 8.2++ | −18 ± 10.2 | −5.4 ± 5.4oo | −6.9 ± 5.3++ | −9.6 ± 11.0 | −3.3 ± 8.8o | −5.5 ± 9.4 |

oP < 0.05, ooP < 0.001 for initial vs. mid measurement, +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.001 for initial vs. last measurement, NA: not available.

Changes in Group B from the initial to the last measurement

Figures 3 and 4 show the increase in fluid status in Group B. In this group, the fluid status was increased significantly (P < 0.001). The recorded adverse events reduced significantly from 25.7% ± 10% to 6.9% ± 7.8%, (P < 0.001), while all other clinical parameters including the blood pressure and the ejection fraction did not change.

Discussion

The availability of an objective, patient-specific determination of normohydration is of key importance for the improvement of fluid management in haemodialysis patients [26]. Following initial measurements with the BCM in the dialysis centre involved in this study, the fluid overload was found to be FOpre/ECW >15% in 25% of patients. These findings are in agreement with a recent publication showing that 25% of patients from a large haemodialysis population exhibit a fluid overload of >2.5 L (FOpre/ECW>15%) before dialysis treatment [23]. Wizemann [27] showed that this fluid overload leads to a more than 2-fold increase in mortality risk.

The reason for the observed fluid overload in Group A was further investigated. Fifty percent of the patients in Group A were referred at a very late stage to the HD treatment from the pre-ESRD care, 25% of all patients in Group A were referred late after a failing transplant and one patient was switched from PD to HD. In all these cases, the high fluid overload was not unexpected, the late referral remains a problem that needs to be addressed in the future [28]. In Groups B and C, only 16% and 18.5% of patients were late referrals, respectively.

Previous works have suggested that patients might benefit from assessing and maintaining fluid status by an objective method [2,29,30]. Prior to the current study, there have been no reports in the literature demonstrating the achievement of normohydration in a complete dialysis centre.

The purpose of this study was to investigate if the patients might benefit from an improvement in fluid status towards the normohydration range provided by the BCM [31].

It was decided that the weight representing the normohydration target should be approached slowly and carefully allowing the cardiovascular system sufficient time to adapt to the changes in fluid status. The post-weight was changed by <0.5 kg (<0.7% of dry body weight) in 1 week. The increase in post-weight in Group B (adverse event group) was performed with the highest caution ensuring that there was no occurrence of clinical signs of overhydration in the interdialytic interval. We believe that while it is important to approach the target of normohydration slowly, it is equally important not to lose sight of this target. Using this strategy, it was possible to modify the fluid status in incident and established dialysis patients towards normohydration without causing additional intra- or interdialytic adverse events. Furthermore, the reductions in fluid overload made a significant reduction in the antihypertensive medication achieveable.

Already after an observation period of 6 months, it was possible to observe an improvement in the patient status. To exclude any seasonal effects (initial measurement winter, middle measurement summer, last measurement winter), the observation period was extended to more than 1 year (400 ± 139 days).

Benefits for patients in Group A

The benefits for patients in Group A caused by the normalization of the fluid status were demonstrated by the reduction in blood pressure and antihypertensive medication.

Recently, Agarwal [32] could show in a randomized controlled trial in hypertensive patients (n = 100) that a reduction in predialytic weight of 1 kg over an 8-week interval resulted in a reduction of predialytic systolic blood pressure of 6.6 mmHg. In our study, the hyperhdrated Group A patients showed a comparable initial blood pressure (153 ± 14 mmHg vs. 159 ± 16 mmHg), but the reduction was twice as large (12.5 mmHg per 1 L reduction of FO over 1 year) without an increase in intradialytic adverse events. This might show the advantage of classifying the patients by hydration status and targeting for the normohydration status instead of using the probing for dry weight concept in hypertensive patients.

In addition to the improvement in blood pressure, a concomitant increase in ejection fraction was observed. More detailed analysis of the impact of a reduction in fluid overload on left ventricular hypertrophy and ejection fraction should be the topic of further research.

Benefits for patients in Group B

The baseline rate of adverse events (4 weeks prior to the initial BCM measurement) was found to be 25% in patients of Group B. Group B patients presented an elevated systolic blood pressure (BPsys pre_initial = 155 ± 27 mmHg) even though many patients were normohydrated at the start and severely dehydrated at the end of the dialysis session (FOpost_initial = −2.3 ± 1.2 L). In this group, the blood pressure might have been increased due to non-fluid-linked reasons (vascular stiffness, renin over activity, …). Thus, the blood pressure was used as an indicator for increased fluid status, which was misleading in this patient group. It must be highlighted that before the study, no clinical methods for the detection of underhydration were available in the participating dialysis centre. Increasing the fluid status very carefully by 1.3 L led to a significant reduction in the intradialytic adverse events (reduction by 76%). It is essential to separate patients with hypertension due to fluid overload from patients in whom the hypertension has other reasons [23].

Randomized controlled trials would strengthen the findings reported in this study. In order to better demonstrate improvements in the cardiac function such as the reduction of left ventricular hypertrophy, other techniques involving magnet resonance tomography should be employed [33,34]. In the current study, the diet of the patients was not reviewed as proposed by various working groups [8,35]. Therefore, there is a scope in future studies to investigate the effects of dietary salt intake using the analysis methods we have proposed.

Conclusion

The fluid status of haemodialysis patients can be quite different, even if they are managed by the same clinical team. The advantage of an objective target in routine clinical practice is self-evident. We have shown that the normohydration target determined with the BCM can be achieved in all prevalent and incident patients of one dialysis centre. Increasing the fluid status slightly in patients who presented intradialytic adverse events and were dehydrated reduced the intradialytic events dramatically. Reduction of fluid overload, hypertension and antihypertensive medication was possible by a slow reduction of post-dialysis weight in hyperhydrated patients.

Acknowledgments

Dr Kral and Dr Blazka performed the ECHO measurements.

Conflict of interest statement. All authors are employees of Fresenius Medical Care.

References

- 1.Dorhout Mees EJ. Cardiovascular Aspects of Dialysis Treatment: The Importance of Volume Control. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Passauer J. Dialysis hypotension: do we see light at the end of the tunnel? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:3024–3029. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.12.3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steuer RR, Conis JM. The incidence of hypovolemic morbidity in hemodialysis. Dial Transplant. 1996;25:272–281. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaeger JQ, Mehta RL. Assessment of dry weight in hemodialysis: an overview. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:392–403. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V102392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leypoldt JK, Cheung AK, Delmez JA, et al. Relationship between volume status and blood pressure during chronic hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2002;61:266–275. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pierratos A. Daily nocturnal home hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1975–1986. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan CT, Floras JS, Miller JA, et al. Regression of left ventricular hypertrophy after conversion to nocturnal hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2235–2239. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozkahya M, Ok E, Toz H, et al. Long-term survival rates in haemodialysis patients treated with strict volume control. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:3506–3513. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wizemann V, Wabel P, Chamney P, et al. The mortality risk of overhydration in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1574–1579. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wizemann V, Rode C, Wabel P. Whole-body spectroscopy (BCM) in the assessment of normovolemia in hemodialysis patients. Contrib Nephrol. 2008;161:115–118. doi: 10.1159/000130423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cole KS, Cole RH. Dispersion and adsorption in dielectrics. J Chem Phys. 1941;9:341–351. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole KS, Li CL, Bak AF. Electrical analogues for tissues. Exp Neurol. 1969;24:459–473. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(69)90149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moissl UM, Wabel P, Chamney PW, et al. Body fluid volume determination via body composition spectroscopy in health and disease. Physiol Meas. 2006;27:921–933. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/27/9/012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamney PW, Wabel P, Moissl UM, et al. A whole-body model to distinguish excess fluid from the hydration of major body tissues. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:80–89. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wabel P, Chamney PW, Moissl U, et al. Reproducibility of bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) for the assessment of body composition and dry weight. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:255A. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wabel P, Chamney PW, Moissl U, et al. Reproducibility of bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) in health and disease (abstract) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(Suppl 6):VI 137. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Plum J, Schoenicke G, Kleophas W, et al. Comparison of body fluid distribution between chronic hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients as assessed by biophysical and biochemical methods. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;2001:2378–2385. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.12.2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraemer M, Rode C, Wizemann V. Detection limit of methods to assess fluid status changes in dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1609–1620. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moissl U, Bosaeus I, Lemmey A, et al. Validation of a 3C model for determination of body fat mass. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:257A. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moissl U, Wabel P, Chamney PW, et al. Validation of a bioimpedance spectroscopy method for the assessment of fat free mass. NDT Plus. 2008;1(Suppl 2):ii215. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Passauer J, Miller H, Schleser A, et al. Evaluation of clinical dry weight assessment in haemodialysis patients by bioimpedance-spectroscopy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:256A. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wabel P, Rode C, Moissl U, et al. Accuracy of bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) to detect fluid status changes in hemodialysis patients (abstract) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(Suppl 6):VI 129. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wabel P, Moissl U, Chamney P, et al. Towards improved cardiovascular management: the necessity of combining blood pressure and fluid overload. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:2965–2971. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agarwal R. Assessment of blood pressure in hemodialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2002;15:299–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139x.2002.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daugirdas JT. Second generation logarithmic estimates of single-pool variable volume Kt/V: an analysis of error. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;4:1205–1213. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V451205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kooman J, Basci A, Pizzarelli F, et al. EBPG guideline on haemodynamic instability. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(Suppl 2):ii22–ii44. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wizemann V, Rode C, Chamney PW, et al. Fluid overload and malnutrition assessed with bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) are strong predictors of mortality in hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant Plus. 2008;1(Suppl 2):ii16–ii17. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dogan E, Erkoc R, Sayarlioglu H, et al. Effects of late referral to a nephrologist in patients with chronic renal failure. Nephrology (Carlton) 2005;10:516–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2005.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charra B. Fluid balance, dry weight, and blood pressure in dialysis. Hemodial Int. 2007;11:21–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2007.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wystrychowski G, Levin NW. Dry weight: sine qua non of adequate dialysis. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007;14:e10–e16. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wabel P, Chamney P, Moissl U, et al. Importance of whole-body bioimpedance spectroscopy for the management of fluid balance. Blood Purif. 2009;27:75–80. doi: 10.1159/000167013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agarwal R, Alborzi P, Satyan S, et al. Dry-weight reduction in hypertensive hemodialysis patients (DRIP): a randomized, controlled trial. Hypertension. 2009;53:500–507. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.125674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mark PB, Patel RK, Jardine AG. Are we overestimating left ventricular abnormalities in end-stage renal disease? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1815–1819. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mark PB, Doyle A, Blyth KG, et al. Vascular function assessed with cardiovascular magnetic resonance predicts survival in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2008;10:39. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-10-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toz H, Ozkahya M, Ozerkan F, et al. Improvement in ‘uremic’ cardiomyopathy by persistent ultrafiltration. Hemodial Int. 2007;11:46–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2007.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]