Abstract

Objectives:

To understand how children living with parental mental illness (PMI) understand mental illness (MI) and what they want to tell other children.

Method:

The study design was a secondary analysis of a grounded theory study exploring Canadian children’s perceptions of living with PMI. Interviews from 22 children, ages 6 – 16, living with a parent with depression, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia receiving treatment for the MI, were re-read, coded and analyzed along with data categories, their properties, field notes and memos from the original data.

Results:

Children revealed that they had limited understanding of MI and received few factual explanations of what was happening. Limited information on MI caused undue hardship. Younger children worried about their parent dying, while older children also were concerned about developing MI. Children offered suggestions for other children in similar circumstances.

Conclusions:

This study raises awareness of children living with PMI and identifies them as a population requiring services. It incorporates children’s perceptions of what they know and need to know. Children require assistance to understand and to respond to PMI. Mental health and primary health care clinicians have opportunities to assist these children within collaborative care models developed in conjunction with school services.

Keywords: children, adolescents, parents, mental illness, grounded theory

Résumé

Objectifs:

Expliquer comment les enfants qui vivent avec un parent souffrant de maladie mentale perçoivent cette maladie et l’expliquent aux autres enfants.

Méthodologie:

Analyse secondaire d’une théorie factuelle qui étudie la manière dont les enfants canadiens perçoivent la maladie mentale de leur parent. Vingt-deux sujets âgés de 6 à 16 ans, dont un parent était traité pour dépression, trouble bipolaire ou schizophrénie, ont été interrogés. Les faits, les données et leur propriétés, les notes prises lors de l’entrevue et les originaux des notes de service ont été à nouveau consultés, codifiés et analysés.

Résultats:

Les enfants ont déclaré qu’ils comprenaient mal la maladie mentale et qu’on leur donnait peu d’explications concrètes sur ce qui se passait. Ce manque d’information engendre une souffrance inutile. Les enfants plus jeunes avaient peur que leur parent meure, les plus âgés craignaient de souffrir de maladie mentale plus tard. Ces enfants faisaient des suggestions aux enfants qui vivaient une expérience similaire.

Conclusions:

Les enfants dont le parent souffre de maladie mentale constituent une population qui a besoin de services de santé; cette étude indique ce que les enfants savent et ce qu’ils doivent savoir. Les cliniciens en santé mentale et les intervenants de première ligne peuvent aider ces enfants en appliquant les modèles de soins collaboratifs mis en place avec les services scolaires.

Keywords: enfants, adolescents, parents, maladie mentale, théorisation ancrée

Statistics indicate that one in five Canadians will suffer from a mental illness (MI) throughout their life time (Government of Canada, 2006). While statistics on parenting are not routinely collected, past estimates suggest that 50% of people with MI are parents (Gopfert, Wolpert & Seeman, 1996). National survey data from the Canadian Community Health Survey Mental Health and Well Being (CCHS 1.2) revealed 12.1% of Canadian children under 12 live with parents meeting the diagnostic criteria for mood, anxiety or substance abuse within the past year. In addition, 17% of children live in lone parent households. These statistics underestimate the prevalence rate (Bassani, Padoin, Philipp & Veldhuizen, 2009). Research has established that children of parental MI (PMI) are at increased risk for mental health and behavioural problems, suicidal ideation and interpersonal difficulties (Wickramaratne & Wesissman, 1998). However, few resources are allocated to parenting or children (Ackerson, 2003; Mordoch & Hall, 2002). Parents and their children are also victimized by the societal stigma and discrimination accompanying MI within Canadian society (Stuart, 2005).

Although Phillips (1983) identified that service providers regularly miss opportunities to intervene with children, Nicholson and Biebel (2002) noted this continues to be problematic. A culture of non-intervention in the organization of health and welfare services may inhibit prevention and early intervention efforts for this population. Thus children are left with few resources to assist them.

A volume of research on children of PMI exists but the majority of this research is based on behavioural competence measures and adults’ perceptions of children’s experiences. Few research studies incorporate children’s perspectives. Previous literature focused on risks associated with genetic transmission (Rosenthal, 1970) exposure to parents’ pathology (Rutter, 1966) and the effects of multiple risk and protective factors (Werner & Smith, 1992). During the decade of the eighties, the research approach shifted from a disease model to a health promotion model resulting in extensive literature on children’s resiliency (Anthony & Cohler, 1987; Garmezy, 1987; Rutter, 1985). However, this literature mainly relied on imposed views of resiliency filtered through adult eyes and focused on behavioural competence which minimized children’s subjective experiences (Mordoch & Hall, 2002).

Currently, there is renewed interest in children living with PMI. Australia has provided a decade of strong leadership in identifying children’s needs (Cowling, 1999) and the World Health Organization supported the 2009 European conference on children of PMI: The Forgotten Children (World Psychiatric Association News, 2009). While a body of current research is developing most children continue to manage their circumstances with little information or formal intervention (Mordoch & Hall, 2008).

Children in the research process

In this paper, the term children is used to describe all participants under the age of majority. Qualitative studies encourage children to express their perceptions and provide an understanding of the context of their lives (Davies & Wright, 2008). Adults’ views of children’s experiences may differ greatly from children’s accounts (Lightfoot, Wright, & Sloper 1999). This paper assumes that the inclusion of children’s perspectives in research generates knowledge that if used, will facilitate the bridging of services for children and their parents. While quantitative research has made significant contributions, it has insufficiently addressed children’s perspectives and the multiple social and cultural contexts of their experiences (Graue & Walsh, 1998). Children are not regarded as the primary source of knowledge on their experience. Rather the child’s experience is filtered through their parents, distancing the researcher from the child’s unique world and denying children the opportunity to speak about situations concerning them (Oakley, 2000).

Method

This paper is a secondary analysis of a qualitative grounded theory study on how children perceived and managed living with PMI. In qualitative research the data provide rich detailed description of the participant’s social world and its constraints. This supports a secondary analysis wherein data are reanalyzed for purposes of answering new questions, more fully examining the original question, and expanding concepts (Thorne, 1994). In grounded theory, analysis yields categories (concepts) that capture the underlying patterns in the data. These emerge from systematic data coding and constant comparative analysis of incidents (Glaser, 1998). Within this process, some categories or their properties may not be fully developed in order to focus on the original research questions.

This secondary analysis focused on further investigation of a property (component) of the category Monitoring, developed in the primary analysis. Monitoring was a process whereby children monitored cues in their parents’ physical appearance, interactions, activities and mood (See Mordoch & Hall, 2008 for detail). A property of monitoring, Having part of the story, prompted the secondary research questions. The purpose of this secondary analysis was to answer the following questions: How do children understand and learn about MI? What do they want to tell other children living with PMI?

Sample

The sample consisted of 22 English speaking children aged 6 – 12 years who lived full or part time with a parent with a MI. The parent had a primary diagnosis of depression, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia and was receiving treatment. Fourteen boys and 8 girls were interviewed, with 11 children aged 6–12 years and 11 children aged 13–16. The study was conducted in a mid-size Canadian city. Some children were interviewed twice. For full description of the sample, see Mordoch & Hall, 2008.

Data Analysis

Interviews and data categories from the original study that were linked to the focus of the secondary analysis were re-read along with the original memos and field notes. This process ensured there was sufficient data to answer the research questions. All transcribed and audio-taped interviews, corresponding participant observation and field notes were readily accessible. Audio tapes of selected interviews were replayed to clarify coding categories and levels of conceptual abstraction. Art collected in the original study was reviewed in the context of the secondary analysis questions. The analysis followed the principles of open (all is coded), selective (focused on the emergent categories) and theoretical codes (conceptualization of the relationship of codes) (Glaser, 1998).

Rigour of the analysis

An audit trail documented decisions related to coding. Grounded theory criteria of fit (the relationship of the core variable to the problem being studied) and work (the ability of the core variable to relate the other concepts to the core variable) were upheld in the analysis by intensive attention to levels of coding and integration of memos (Glaser, 1998). Reflexivity, the influence of the researcher/participant relationship on the construction of the data, was addressed in memos, field notes and intercollegial dialogue. Credibility and authenticity of the findings was supplemented by a rich and dense data set and conscious attention to researcher influence.

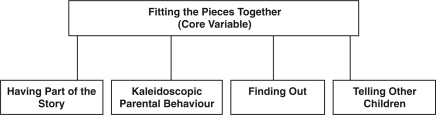

Findings: Fitting the Pieces Together

The secondary analysis generated the core variable, Fitting the Pieces Together with properties of: having part of the story, kaleidoscopic parental behaviour, finding out about MI, and telling other children. Fitting the Pieces Together (Figure 1) refers to the children’s struggle to make sense of the limited information available to them while living with PMI. To clarify their understanding of PMI, children had to make sense of information they received or that inadvertently came across their paths.

Figure 1.

Core Variable with properties

They (adults) don’t get them (children) help…... They don’t speak to the kids about it….They (children) should know that, if he (Father) had that illness he wouldn’t be himself, like right away you’d see it like this.

(Boy Age 11).

In trying to fit the puzzle together other concerns were raised:

The kid is eventually gonna figure out that you’re lying to them. I think that could be the start of a kid saying, well, if the doctors can lie and Mommy and Daddy can lie, then I can lie.

(Girl Age 16).

Children needed enough information about MI to help them live with their circumstances, avoid unnecessary emotional duress and give them hope for the future; “once I understood, things were better.” (Girl Age 16).

Having Part of the Story: “You don’t get life insurance. What’s life insurance?”

There was consensus across the interviews that most children were not well informed and that MI was not openly discussed. This suggested that MI was not important; “I’m not thinking that it is (MI) not important. It just seems like it’s not important if people don’t talk about it, learn about it, or know about it” (Girl Age 14). This idea was reinforced in insidious ways. For example, reflecting on a school Career Day, this child noted: “Different people speak about their careers. There wasn’t anything to do with mental health. ….There was no representation of that... There was every other thing under the sun, …even bartending.” (Girl Age 16).

Silence around mental illness misinformed children’s perceptions. While not privy to information, children were still expected to manage their circumstances. For example, this child reflected on her experience with acute PMI: “She didn’t really tell me. She was talking about it, sort of, and I was sitting beside her giving her a glass of milk and …lots of huggies.” (Girl Age 7). The child did not receive any explanation for her mother’s acute illness and was left feeling uncertain as to what was happening.

Vague explanations and efforts to shield children escalated their concerns. An older child observed: “The kid eventually starts thinking …there’s something definitely not right here, either my dad’s dying or there’s something you’re not telling me.” (Girl Age 16). This sense of vagueness created unnecessary worry and ambiguity around what was happening and the nature of MI. The child continued:

It’s better for kids to know …. you’ll ask what’s happening and your parents don’t tell you,…..They don’t want to cause you any stress. I don’t think parents realize, it causes more stress not to know what’s going on…You’re lost as to what’s happening.

(Girl Age 16).

Hospitalization of a parent triggered images of physical illness causing children concern the parent would die: “That mommy will get really sick and die. That the same thing will happen to their (other children’s) mommies and they don’t probably feel safe” (Girl Age 6).

Children had difficulty understanding hospitalization for a mental illness. Consequently, hospitalization was associated with physical illness and unwarranted fears that their parent was dying. This caused undue hardship for children.

The essence of having part of the story and its impact on children is best captured in the following response from a 9 year old boy: “It‘s (parent being ill) not that fun, you don’t get life insurance. That’s kinda (sic) bad thing, I think. {Pause…….} What’s life insurance?” This child had overheard a family discussion related to life insurance and his father’s illness. The child inferred that life insurance was desirable but unattainable. Having partial understanding of the situation, he was left unsure and worried about the implications. Children had pieces of information that they did not completely understand but sensed something was wrong. This was further reinforced with changes in parental behaviours.

Kaleidoscopic parental behaviour

A kaleidoscope is a tube containing loose bits of colored material and two mirrors at one end that shows many different patterns as it turns (Merriam-Webster, 1995). Children understood MI as diverse patterns of parental behavioural changes. Much like the turn of a kaleidoscope, these changes were often predictable patterns but held elements of unpredictability (Mordoch & Hall, 2008). MI was understood as changing patterns in physical health and social behaviours: “There’s when they’re always sitting alone. Like they’re by their selves...and one more sign is when you talk to someone it takes them a while to register what you ask them.” (Boy Age, 9).

Children understood MI as decreased functioning of their parent: An 11 year old boy stated: “It’s kinda hard to like get a hold of good jobs and stuff like that”. Behavioural changes in activities with children were noted “they (parents) lose interest in things they used to like and they get sadder and sadder.” (Girl Age 10). The first line of this child’s drawing (Figure 2) illustrates the parent becoming sad for no apparent reason. The second line illustrates the mother losing interest in examining a ladybug, previously a favourite pastime of the child and parent.

Figure 2.

Drinking could be an indication that something was wrong: “I could tell when she’s getting upset, because … she’d drink and start saying really depressing things.” (Girl Age 16). Some changes shattered the children’s sense of safety. These parental behavioural changes could lead to chaos. This boy was chronically unable to sleep because he did not know what was happening and who was in his home.

My sister started bringing her friends over. They’d drink and do drugs. My mom couldn’t really do anything because she’d be depressed, she didn’t know what to do. So she’d...sit back and pretty much watch it...I couldn’t sleep.

(Boy Age 14).

Children understood that MI signified unpredictable behaviour in their parents:

“she’ll get just really mad for no reason…stuff she usually wouldn’t get mad about. Cause she’s a pretty nice mom.”

(Boy Age 13).

Some unpredictable changes from the parent’s routine behaviour frightened children:

She is getting better with night terrors and screaming...when she did, it freaked me out...She said ‘Don’t be afraid to wake me up’...And I poked her and she went whipping around. I got so scared.

(Girl Age 11).

Children recognized patterns and unpredictability in parental behaviour. They incorporated these observations into their understanding of MI. Children’s understanding was fragmented and constructed over time within a context of ambiguity. How then did children gather information about MI?

Finding out - How do children obtain information?

Children learned about MI through parents and family, school counsellors, overhearing adults’ conversations, printed materials, by chance, and via the media. Some parents explained MI and their behaviours to their children. Extended family or the well parent would sometimes interpret parental behaviour to the child or give advice on what to do when the parent was ill.

Conversations inadvertently overheard provided information. In times of crisis, children could not help but overhear household conversations discussing the parent’s situation.

I could hear the phone. I could also hear their talking even when they hang up. I just sit here...I don’t really want to hear but it is part of my home. See eavesdropping is picking up the phone and listening. It’s not that.

(Boy Age 10).

Children interpreted these conversations on their own: “I heard she was talking on the phone to one of her doctors. I could not hear what she was saying and I never asked her…She has a kind of a fainting disability or something like that.” (Boy Age 13). Although living with a chronically ill parent, this was the child’s only source of information on mental illness.

Children occasionally came across information at school informing them about drugs and MI: “I read it in one of these. It was called Marijuana…the teachers gave it to us. There was another one that said that people with MI should not use cannabis (Boy Age 16). The boy wanted to share this pamphlet with his parent and his siblings. It had considerable impact on him due to his fear of becoming mentally ill: “I can avoid it (marijuana). Something like that might trigger me (to have MI). I told D. (brother) about it. I don’t think my younger brothers know…that drugs can trigger it. They are too young.”

Children also learned about MI by chance. One child learned about brain functioning and anti-depressants in a reading comprehension paper. This provided valuable information about her mother’s MI. Media reports of celebrities experiencing addictions and suicide informed older children, although the credibility of these reports was unclear.

Accessing information about MI was elusive. When thinking of accessing health information, this child identified that there were places for finding out about cancer but was unsure about where you would find out about MI: “Where do people find out about cancer? Isn’t there a place like that for MI?” (Girl Age14). Children did not know where to turn for information.

My father has the illness....I gotta understand it more. I wanna (sic) know symptoms of it. I’d like to …try to prevent it...If I go to a hospital to talk to a MI doctor there, he’d probably just tell me to get out of here; we’re too busy.

(Boy Age 16).

Telling other children: What other kids need to know

Children described what they wanted to tell other children. They felt children should know about MI but should be told in ways that are not “scary”. Children suggested that adults could help children understand. They suggested strategies:

Something like Magic School Bus, or a video game….That’s a way to inform little kids. I knew about molecules before I knew about, half the stuff I know right now…make a computer game out of facts about different illnesses... make it fun.

(Girl Age 16).

Complex concepts could be explained in fun and creative ways that would help children.

I’d describe a healthy brain as a freshly baked blueberry pie. You know everything is in its right place; it is all organized and ready to eat. A brain with a MI is a blueberry pie that somebody stuck a fork in, mushed it all up and everything is mixed up.

(Girl Age 16).

Children felt that they were the only ones living with PMI; “How would you know, you don’t talk about it” (Boy Age 10). They wanted children to know there are other children in similar circumstances. Children stressed it is important to tell children what to do when the parent is ill. Often children do not know how to handle situations.

They should know not be scared. Kids are scared a lot of the time.…they’re young and they don’t know what’s happening. Just take care, don’t worry. Suck it in. Try to stay strong, focused.

(Boy Age 14).

Despite the difficulties his family had faced, this child felt that they had managed to stay together and he had learned to depend on himself. Other children noted that sometimes being physically close to the parent was not wise and advised “to get out of the same room” in crisis situations and to look after younger siblings. The drawing in Figure 2 illustrates one child’s advice to leave the room and to take younger children with you when the parent becomes irritable.

Children were sensitive to problems at school:

Kids bothering you if they find out that your parents have a MI and they make fun of you, just laugh it off…so they know they’re not getting to you…just let it go in one ear, out the other.

(Boy Age 14).

Some children were frequently changing schools due to their families’ relocation. This was likely a contributing factor towards being bullied.

Children believed that all children knew little about MI. They might think it is “like being mentally challenged” but it is different. They felt it was important to: “Help people understand what people do not know about MI” (Boy Age 14). Children understood that parents need help and it is not the parent’s or the child’s fault. Children identified ways to help the parent and wanted to inform other children: “Parents need help and children can talk to them, try and understand what is wrong: Sometimes you have to take care of your parent. If they drink coffee, get them a coffee.” (Boy Age 14).

Children need to know that while medication may help their parent, medication should not be used by everyone: “Medication isn’t always the way to take care of your problems…The kid needs to realize that the medication, the food, makes parents feel better because something is wrong with them.” (Girl Age 16). Children wanted other children to know what had helped them and hoped this would help other children.

Children recognized that their parent was more than the MI. Most children valued the significant contribution parents made to their lives: ‘It’s not like we don’t love her cause she’s got a mental illness...her heart’s still there and she cares about me and K (sister)” more than anything.’ (Boy Age 13). From their lived experiences children understood that MI was “not 24/7”, and was “not all bad, you know.” One child (Girl Age 11) drew a heart around her mother “cause I love her.” (Figure 3). She recognized mental illness made her mother different from other mothers.

Figure 3.

Discussion

Fitting the Pieces Together described the process whereby children tried to understand PMI. Children recognized patterns of change and unpredictability in their parents’ behaviours. They understood PMI based on observations, sporadic information from families and occasionally teachers or counsellors, in addition to pamphlets, media, and happenstance. This struggle to understand PMI is identified in other studies (Cowling, 1999; Fudge & Mason, 2004).

Based on their experiences, children wanted to inform other children of helpful ideas to manage their circumstances. Doing so helped them feel less isolated. Foster, O’Brien and McAllister (2005) found that children living with PMI were unaware of other children in similar circumstances and that knowing of them was helpful. Children were sensitive to the stigma around MI which impeded their understanding. Protecting children from factual information about MI is identified as a barrier preventing parents from discussing their illness (Stallard, Norman, Huline-Dickens, Salter & Cribb, 2004). Children, however, state they know something is wrong and shielding them causes more concern. Literature that advises caregivers how to talk to children during acute illness, states that children should be informed that with treatment and support, their parent’s condition will improve (Chovil, 2004). Health care providers need to understand that children have questions which require answers from a trusted and empathic adult. Research on when and what to tell children is needed to ensure that all children receive timely and developmentally appropriate information. This study demonstrated children experienced undue hardship when imagining parental health outcomes based on incomplete information.

The role of schools in providing support for children of PMI and education on MI is crucial in service provision (Foster et al., 2005; Fudge & Mason, 2004). Fox, Buchanan-Barrow and Barret (2008) identified that children generally adopt societal attitudes towards MI and therefore it is not surprising that children of PMI might be subject to ridicule. Schools need to assist children who may be teased and ensure that additional burden is not placed on these children.

Roose and John (2003) found children to be articulate, aware and capable of providing important perspectives on mental health. Efforts to include children’s views, particularly children who are socially excluded, require support and consideration in service development (Day, 2008). Europe and the United Kingdom are addressing children’s exclusion from meaningful participation in research, theories and policies that affect them. In the United Kingdom, children of PMI are increasingly recognized as ‘carers’ of their parents with MI. Young ‘carers’ projects assist with respite and leisure while recognizing the significant amount of work that children contribute, often within positive parent/child relationships. Additional services include one to one befriending, homework clubs and support to families (Aldridge, 2005). While efforts to include children have prevailed, there is little evidence of the impact of their perspectives on policy (Hill, Davis, Prout & Tisdall, 2004). In Canada, strategies that include children’s voices and utilize their opinions are needed to transform services. Waddell et al. (2005) question why Canadian mental health policy does not reflect research evidence on children and posit that researchers and policy makers can work collaboratively towards positive change.

This study is clinically significant as it increases this population’s visibility within the mental health system. Given the 20th anniversary of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Child (UNCRC) the findings are timely. All children have the right to get and share information that is not damaging to them or others; to voice and have their opinions heard on what should happen when adults are making decisions affecting them (www.rightsofchildren.ca). Children have a right to voice their perceptions on living with PMI and health care providers have the responsibility to listen, to assist and protect children. While all parents of the children in the study had recent contact with the mental health system, few children recalled any interaction with a health care professional. Given that 12.5% of Canadian children are estimated to live with PMI (Bassani et al., 2009) and are considered to be at increased risk of pathology, a systematic approach to assessing and addressing these children’s issues is urgently needed within the primary care and mental health systems.

Conclusion

This secondary analysis of a grounded theory study on children’s perceptions of living with PMI provides information on how children understand and learn about MI and what they want other children to know. Little formal intervention assists children in their understanding of MI. Children require services that minimize the ill effects of PMI, maximize family strengths and maintain the safety of children. Primary health and mental health care providers have an opportunity to respond to children’s concerns and work collaboratively to meet their needs.

Acknowledgements/Conflict of Interest

The authors have no financial relationships or conflicts to disclose.

References

- Ackerson BJ. Parents with serious and persistent mental illness: Issues in assessment and services. Social Work. 2003;48(2):187–194. doi: 10.1093/sw/48.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge J. The experiences of children living with and caring for parents with mental illness. Child Abuse Review. 2008;15:79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony EJ, Cohler B. The invulnerable child. New York, NY: The Guildford Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bassani D, Padoin D, Philipp C, Veldhuizen S.2009Estimating the number of children exposed to parental psychiatric disorders through a national health survey Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 36doc.1186/11753-2000-3-6. available from http://www/capmh.com/content/3/1/6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chovil N. Talking to children and youth. When it’s time to discuss a family member’s mental illness or alcohol/drug problem. Visions. 2004;2(2):35–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cowling V. Finding answers, making changes. Research and community project approaches. In: Cowling V, editor. Children of Parents with a Mental Illness. Melbourne: ACER; 1999. pp. 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Davies J, Wright J. Children’s voices: A review of the literature pertinent to looked-after children’s views of mental health services. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2008;13(1):26–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2007.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day C. Children’s and young people’s involvement and participation in mental health care. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2007;13(1):2–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2007.00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox C, Buchanan-Barrow E, Barrett M. Children’s understanding of mental illness. An exploratory study. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2008;34(1):10–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster K, O’ Brien L, McAlister M. Addressing the needs of children of parents with a mental illness: Current approaches. Contemporary Nurse. 2005;5(18):67–80. doi: 10.5172/conu.18.1-2.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fudge E, Mason P. Australian e-journal for the advancement of mental health. Consulting with young people about service guidelines relating to parental mental illness. 2004;3(2):1446–7984. [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N. Stress, competence, and development: Continuities in the study of schizophrenic adults, children vulnerable to psychopathology, and the search for stress-resistant children. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57(2):159–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG. Doing grounded theory: Issues and discussions. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gopfert M, Webster J, Seeman MV. In: Parental psychiatric disorder: Distressed parents and their families. Gopfert M, Webster J, Seeman MV, editors. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Graue ME, Walsh DJ. Studying children in context: Theories methods and ethics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium JF, Holstein JA. The new language of qualitative method. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada The Human Face of Mental Health and Mental Illness in Canada 2006

- Hill M, Davis J, Prout A, Tisdall K. Moving the participation agenda forward. Children and Society. 2004;18:77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoot J, Wright S, Sloper P. Supporting pupils in mainstream schools with an illness or disability: Young people’s views. Child: Care, Health, and Development. 1999;25(4):267–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.1999.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster’s New Complete Dictionary. Merriam-Webster; New York: Smithmark Publishers; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mordoch E, Hall WA. Children’s perceptions of living with a parent with a mental illness: Finding the rhythm and maintaining the frame. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(8):1127–1144. doi: 10.1177/1049732308320775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mordoch E, Hall WA. Children living with a parent who has a mental illness: A critical analysis of the literature and research implications. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2002;16(5):208–216. doi: 10.1053/apnu.2002.36231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson J, Biebel K. Commentary on “community mental health care for women with severe mental illness who are parents” - the tragedy of missed opportunities: What providers can do. Community Mental Health Journal. 2002;38(2):167–172. doi: 10.1023/a:1014551306288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley MW. Children and young people and care proceedings. In: Lewis A, Lindsay G, editors. Researching children’s perspectives. Buckingham: Open University Press; 2000. p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips I. Opportunities for prevention in the practice of psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1983;140(4):389–395. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal D. Genetic theory and abnormal behaviour. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity. Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;147:598–611. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Children of sick parents: an environmental and psychiatric study. (Monograph No. 16) London: Maudsley; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Roose GA, John AM. A focus group investigation into young children’s understanding of mental health and their views on appropriate services for their age group. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2003;29(6):545–550. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2003.00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallard P, Norman H, Huline-Dickens S, Salter E, Cribb J. The effects of parental mental illness upon children: A descriptive study on the views of parents and children. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;9(1):39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart H.2005Fighting stigma and discrimination is fighting for mental health Canadian Public PolicyXXX1 supplement S22–S28.

- The United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child 1989. Retrieved from the Canadian Coalition for the Rights of Children, http://www.rightsofchildren.ca November 23, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. Secondary analysis in qualitative research: Issues and implications. In: Morse JM, editor. Critical issues in qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks: CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 263–279. [Google Scholar]

- Waddell C, Lavis JN, Abelson J, Lomas J, Shepherd CA, Bird-Gayson T, et al. Research use in children’s mental health policy in Canada: Maintaining vigilance amid ambiguity. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:1649–1657. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE, Smith RS. Overcoming the odds: High risk children from birth to adulthood. London: Cornell University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wickramaratne PJ, Weissman MM. Onset of psychopathology in offspring by developmental phase and parental depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37(9):933–942. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Psychiatric Association News, March, 2009.