Abstract

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a noninvasive technique to induce electric currents in the brain. Although rTMS is being evaluated as a possible alternative to electroconvulsive therapy for the treatment of refractory depression, little is known about the pattern of activation induced in the brain by rTMS. We have compared immediate early gene expression in rat brain after rTMS and electroconvulsive stimulation, a well-established animal model for electroconvulsive therapy. Our result shows that rTMS applied in conditions effective in animal models of depression induces different patterns of immediate-early gene expression than does electroconvulsive stimulation. In particular, rTMS evokes strong neural responses in the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT) and in other regions involved in the regulation of circadian rhythms. The response in PVT is independent of the orientation of the stimulation probe relative to the head. Part of this response is likely because of direct activation, as repetitive magnetic stimulation also activates PVT neurons in brain slices.

Electromagnetic induction was first described in 1831 by Michael Faraday. This principle, formulated mathematically by James C. Maxwell, states that fluctuating magnetic fields can induce electric current in conductors placed nearby. Recently, this principle has been applied to induce electric current in the human brain, in a technique known as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) (1). TMS has been used as a diagnostic tool in neurology because it is painless and noninvasive, and it allows a precise spatial and temporal activation of brain regions (2). A variant of TMS, in which the stimulus can be repeated for a few seconds at frequencies up to 50 Hz, is referred to as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) (3, 4). rTMS has been used to study cognitive processes and is currently been investigated as a treatment of psychiatric and neurological disorders (5–9). rTMS induces transient enhancement of mood in healthy subjects, and daily application relieves symptoms of patients suffering from resistant major depression (9–11). rTMS has also been proposed to relieve depression in an animal model (Porsolt swim test) (12, 13). However, neither the precise pattern of brain activation nor the molecular mechanisms underlying the behavioral effects of rTMS are known. It has been recently reported that rTMS induces transcription of the glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in the murine brain. GFAP transcription is up-regulated in astrocytes of the dentate gyrus, and the magnitude of the response depends on the number of stimulus trains (14). Whether rTMS induces GFAP transcription in astrocytes directly or indirectly through neural activation remains to be determined.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) provides highly reliable relief of depressive symptoms, but it requires application of intense electrical stimulation because the skull isolates electric current and because intracerebral structures shunt current directly from one electrode to the other (15). The intensity of stimulation usually used in patients induces a self-sustained after-discharge of cortical neurons, which produces convulsive seizure. Therefore, ECT requires general anesthesia, induces massive autonomic stimulation, and can produce transient memory loss (16). The similar therapeutic effects of rTMS and ECT suggests the following hypothesis: current elicited in brain by electromagnetic induction (rTMS) and current induced by direct application of voltage, such as during ECT, produce overlapping responses. To test this hypothesis, we have produced a map of brain regions activated by rTMS by monitoring expression of immediate-early genes and activation of a transcription factor in rat brain, using rTMS parameters known to have behavioral effects on rats, and we have compared these effects with those elicited by electroconvulsive stimulation [ECS; an animal model for ECT (17)].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Stimulation.

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (180–230 g) were housed in a light-controlled room (7:00 a.m. on, 9:00 p.m. off). rTMS was administrated to awaken animals by using a round coil (5-cm diameter) and the Cadwell Rapid Rate Stimulator (Cadwell, Kennewick, WA) (12, 18), at a rate of 25 Hz for 2 sec with 100% power that generates a field of approximately 2 tesla. The coil was held above the rat’s head at close proximity (dorsally), with the site of stimulation at the orbit level. For orientation experiments, stimulation was applied laterally and ventrally. Control “sham” stimulations were performed to assess the effects of restraining the animals and of acoustic stimulation (peak amplitude approximately 110 dB). Sham stimulations were performed with the coil held at 10 cm above the head (stimulator coil windings parallel to the head plane). rTMS did not produce either notable seizures or changes of behavior, such as excessive struggling. ECS was applied as described (19): briefly, ear clip electrodes connected to an ECT stimulator (unit 7801, Ugo Basile, Varese, Italy) were used on awake, male adult rats (Sprague–Dawley, 180–230 g). Parameters of stimulation (1 sec at 100 Hz, 5-msec pulse width, 90-mA electric current) were chosen to induce maximal convulsive seizures (characterized by catatonia and maximal tonic flexion and extension followed by terminal clonus) with loss of consciousness that lasted for a few seconds (20).

To estimate the induced electric field in different parts of the rat brain, we made measurements in a model system of comparable proportions (21).

In Situ Hybridization.

Animals were decapitated at 45–60 min after stimulation. Radioactive probes were produced by labeling a c-fos specific antisense oligonucleotide (complementary to nucleotides encoding amino acids 1–15) with α-[35S]thio-dATP (Amersham) by using terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase (TdT) (Life Technologies). Hybridization and washing conditions were performed as described (22). Slides were exposed to x-ray film for 3–7 days. Nonradioactive probes: a 2.2-kb c-fos cDNA fragment was inserted into pGEM-4z vector. BamHI-c-fos pGEM-4z and NarI-c-fos pGEM-4z were transcribed in vitro with SP6 and T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of digoxigenin (DIG)-conjugated UTP to produce sense and antisense probes, respectively. Slides were hybridized at 65°C overnight in hybridization buffer, washed in 0.2× SSC at 70°C, and incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-DIG antisera conjugated with alkaline phosphatase. Sections were visualized by using a nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (BCIP) mixture for 1 to 36 hr at room temperature as recommended by the supplier (Boehringer Mannheim).

Immunohistochemistry.

Animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde 90 min after stimulation. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary anti-c-Fos and anti-c-Jun sera (Oncogene) at 1:1000 dilutions. The avidin–biotinylated enzyme complex (ABC) procedure was performed as reported (23) with a kit from Vector Laboratories.

Western Blotting.

Pineal glands and retina were dissected and sonicated in boiling lysis buffer [100 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 6.8/2% SDS/20% (vol/vol) glycerol/10% 2-mercaptoethanol/0.1% bromophenol blue]. Fifteen percent and 50% of total lysates from retina and pineal gland, respectively, were loaded onto SDS/PAGE gradient gels (4–15%) and transferred onto nitrocellulose filters. Filters were incubated overnight at 4°C with 1:3000 dilution of Phospho-CREB antibodies (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY; CREB is cAMP response element binding protein). The blots were visualized in enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham) solution and exposed to x-ray films for 5–20 min.

Brain-Slice Preparation.

Coronal brain slices 400 μm thick from adult rats were cut at the level of the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT) by using a Vibratome (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA) and kept in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF: 126 mM NaCl/5 mM KCl/2 mM CaCl2/2 mM MgSO4/26 mM NaHCO3/1.25 mM NaH2PO4, pH 7.3/20 mM d-glucose, saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2). To reduce the background of c-fos expression induced by cutting, slices were incubated in a home-made interface chamber for 2.5 hr prior to rTMS. Extracellular field potentials were recorded from neocortex and hippocampus to determine if the slices remained healthy. The stimulating coil (25 Hz, 2 sec, 1 train, 100% power) was placed 3 mm above the slices. Thirty minutes later slices were cut into 20-μm sections with a cryostat and processed for nonradioactive in situ hybridization with c-fos probes.

RESULTS

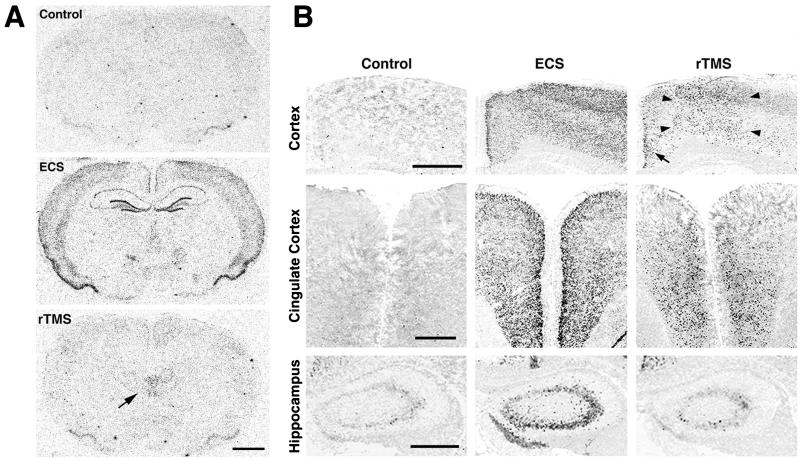

ECS induces a rapid increase of c-fos mRNA expression throughout the brain and, particularly, in hippocampus and neocortex, consistent with previous reports (19) (Figs. 1A and Table 1). By contrast, a single application of rTMS produces a much more discrete stimulation of c-fos mRNA expression. The strongest signal occurs in the dorsal midthalamus, specifically the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT; Figs. 1A and 4). ECS induces c-fos expression throughout various cortical regions, whereas rTMS acts only in the frontal and medial cerebral cortex, including cingulate, primary, and secondary motor cortex (Fig. 1B). The effects of rTMS in the cingulate cortex are more evident in anterior brain sections (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, rTMS does not induce c-fos mRNA expression in lateral cortical regions such as forelimb and parietal cortex. The strong induction of c-fos mRNA expression in the hippocampus by ECS is not observed after rTMS, which produces only a weak response in hippocampal neurons (Fig. 1B). Other brain regions such as midbrain, pons, medulla, and cerebellum do not exhibit any notable induction of c-fos mRNA expression by rTMS. Persistent nonspecific brain responses to, for example, acoustic stimulation or the stress of restraint are minimal, since no changes could be detected in sham-stimulated animals (described in Materials and Methods).

Figure 1.

(A) Expression of c-fos mRNA in adult rat brain after ECS and rTMS. Results of in situ hybridization analyses using an α-[35S]thio-dATP-labeled oligonucleotide probe are shown. Coronal sections of control rats (Top) and rats subjected to ECS (Middle) or rTMS (Bottom) are depicted. ECS and rTMS evoke different patterns of c-fos expression: ECS produces a strong increase of c-fos mRNA expression throughout the cortex and hippocampus, whereas the highest response to rTMS can be observed in thalamic regions, as indicated by an arrow (Bottom). (Scale bar = 2 mm.) (B) Comparative analyses of c-fos mRNA expression after ECS and rTMS in cerebral cortex, cingulate cortex, and hippocampus, as detected by nonradioactive in situ hybridization. ECS induces strong c-fos mRNA expression in all these regions. In contrast, rTMS evokes c-fos expression predominantly in the medial (arrowheads) and cingulate (arrow) cortex. No detectable increase of c-fos expression was observable in hippocampus after rTMS. (Scale bars = 1 mm in all rows.)

Table 1.

Patterns of c-fos mRNA expression induced by rTMS in adult rat brain

| Region | Control | 1× rTMS-D | 1× rTMS-L | 1× rTMS-V | 3× rTMS-D | ECS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cingulate cortex | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| Frontal cortex | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| Parietal cortex | + | + | + | + | + | ++++ |

| Piriform cortex | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++++ |

| Hippocampus | − | −/+ | −/+ | −/+ | + | ++++ |

| Paraventricular nucleus | ||||||

| of the thalamus | ||||||

| Anterior | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | + |

| Middle | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | + |

| Posterior | + | + | + | + | ++ | + |

| Habenular nucleus | − | + | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| Paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Suprachiasmatic nucleus | −/+ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | + |

| Superior colliculus | − | − | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Periaqueductal gray | + | + | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Cerebellum | − | − | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Coronal sections were analyzed with a stereotaxic brain atlas (49). In situ hybridization signals are scaled from − to ++++, where − represents no detectable signal, + background level, and ++++ the highest signal intensity, and NA is not analyzed. rTMS-D, rTMS-L, and rTMS-V depict stimuli applied dorsally, laterally, and ventrally, respectively.

Figure 4.

rTMS activates brain regions controlling circadian rhythms. Induction of c-fos mRNA expression after rTMS can be detected not only in the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT) but also in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) and the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN). Background levels of c-fos mRNA expression in corresponding unstimulated regions are depicted on the left. (Scale bars = 0.5 mm in Top and 0.1 mm in Middle and Bottom.)

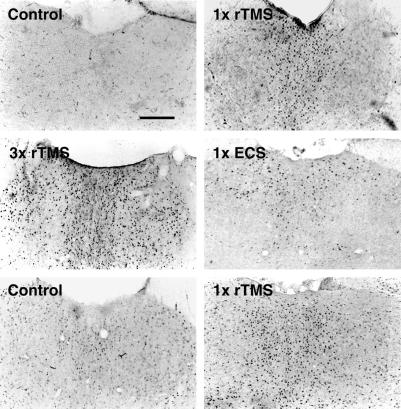

Immunohistochemical analysis confirms that rTMS augments the level of c-Fos and c-Jun proteins in the PVT (Fig. 2). Three trains of rTMS (5-min inter-train intervals) produce a stronger induction of c-Fos in the same brain regions responding to a single stimulation, including the PVT (Fig. 2, Table 1), but moderate c-Fos increase is detected in additional regions, such as in the habenular nucleus and hippocampus (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Immunocytochemical staining of the PVT with c-Fos- and c-Jun-specific antibodies after ECS, rTMS, and either one or three successive applications of rTMS. Background levels of c-Fos-positive nuclei in the PVT are very low (Control, Top). rTMS produces a robust c-Fos induction in PVT neurons (one time rTMS, Top). Three trains of rTMS result in a much higher induction of c-Fos-positive nuclei in this region than a single application (three times rTMS, Middle). ECS produces only a small increase in c-Fos expression in PVT neurons (one time ECS, Middle). The induction of another immediate early gene (c-Jun) was also analyzed: as for c-Fos, rTMS increases c-Jun expression in PVT neurons (one time rTMS, Bottom). However, the background levels of c-Jun expression in these neurons are higher than those of c-Fos (Control, Bottom). (Scale bar = 0.5 mm.)

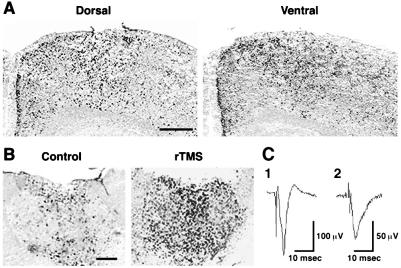

Electric field measurements in a model system showed that at a depth equal to half the radius, the induced electric field had fallen to 40% of its magnitude at the radius; at the center of the spherical model the electric field was reduced by a factor of 30 (ref. 21 and data not shown). To examine whether the site of rTMS application affects the regional pattern of brain responses, we compared the effects when the stimulating coil was placed in different locations on the head. c-fos mRNA induction in the brain, including the PVT and medial cortex, is identical when rTMS is administered dorsally, laterally, or ventrally (Fig. 3, Table 1). We analyzed the effects of rTMS in brain slices to further address the issue of stimulus orientation and to test whether the stimulation of the PVT neurons requires intact neuronal circuitry running outside the plane of the 400-μm-thick coronal slice. rTMS still induces c-fos mRNA expression significantly in the PVT (Fig. 3), suggesting that this region responds directly to rTMS. Only low levels of c-fos mRNA expression are observed in the cortex (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Patterns of c-fos expression induced by rTMS from different orientations in vivo and in brain slices. (A) rTMS elicits the same patterns of c-fos expression, as shown with nonradioactive in situ hybridization, when the stimulating coil is applied to the rat head dorsally (Upper Left) or ventrally (Upper Right). (Scale bar = 0.5 mm.) (B) rTMS is able to stimulate PVT neurons in vitro. Results of a representative experiment are shown. Strong c-fos expression is detected in PVT neurons with nonradioactive in situ hybridization in stimulated brain slices kept in an interface chamber. Experiments were repeated three times. (Scale bar = 0.5 mm.) (C) Extracellular field potentials recorded from coronal brain slices, to test for viability. An extracellular glass recording pipette was placed either in area CA1 of the hippocampus (trace 1) or in the superficial layers of the neocortex (trace 2). Stimulating electrodes were placed in either the hippocampal Schaffer collaterals or in the subcortical white matter. The resulting extracellular field potentials are shown (average of 2). The recordings were performed before application of magnetic stimulation, but at least 3 hr after the slices were made in a standard interface chamber at 33°C.

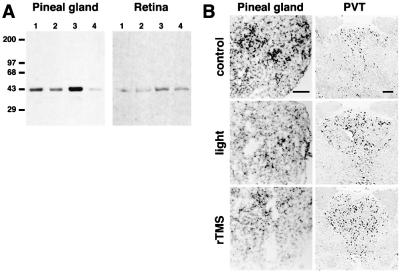

Neurons located in the PVT are interconnected with several brain regions involved in the establishment and regulation of circadian rhythms, which include the subparaventricular zone, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), and the retina (24, 25). The effects of rTMS in these regions were examined in more detail. rTMS induces c-fos mRNA expression in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), as well as in the subparaventricular zone and the SCN (Fig. 4). The effects of rTMS on the retina and pineal gland, where melatonin synthesis is regulated by light and by signals from biological clocks, were analyzed by Western blotting with an antiserum specific for the phosphorylated form of the transcription factor CREB (26–28). Measurements of CREB phosphorylation represent a more sensitive alternative to immediate-early gene detection for molecular changes occurring in tissues after stimulation (23, 27, 28). One application of rTMS produces a transient increase of CREB phosphorylation in the retina and pineal gland. Robust CREB phosphorylation is detected 15 min after stimulation and is strongly reduced within 45 min (Fig. 5). Stimulation using 10% of maximal power is ineffective in inducing CREB phosphorylation in both tissues. It has been shown that a brief exposure (5–10 min) to light during nighttime profoundly affects the level of melatonin synthesis in rats (29, 30) and that light regulates c-fos mRNA expression in the retina (31). Thus, we compared the effects of rTMS and light exposure during the dark phase of the circadian rhythm on c-fos mRNA expression. c-fos mRNA expression in pinealocytes is strongly reduced by rTMS and light exposure (Fig. 5). Because of the extensive connections of PVT with regions that control circadian rhythm, and because PVT neurons respond directly to rTMS, we investigated whether light stimulation at night produces the same effects as rTMS. Both treatments result in increased c-fos mRNA expression in PVT neurons and decreased expression in the pineal gland (Fig. 5). Our results indicate that rTMS particularly affects neurons located in regions involved in setting endogenous biological clocks. When applied during the dark phase of the circadian rhythm, rTMS produces the same effects as light stimulation in pinealocytes and PVT neurons.

Figure 5.

Comparative analysis of the effects of rTMS and light exposure on pinealocytes and retina. (A) Effects of rTMS on pineal gland and retina during the light phase of the circadian rhythm. Western blot analysis of pineal gland and retinal extracts with antisera specific for the phosphorylated form of CREB (pCREB) is shown. Background levels of pCREB in pineal and retina are shown in lanes 1. rTMS at 10% power does not increase pCREB immunoreactivity (lanes 2), whereas rTMS at 100% power is able to induce strong CREB phosphorylation within 15 min (lanes 3). At 45 min pCREB immunoreactivity is reduced in both tissues (lanes 4). Experiments were performed three times. (B) rTMS and light stimulation in the dark phase of the circadian rhythm produce similar changes in c-fos expression in pinealocytes and PVT neurons. Stimulations were performed at 2:00 a.m. (rTMS as described in Materials and Methods; light stimulation 10 min, 40 W). (Top) c-fos mRNA expression in control regions. (Middle and Bottom) c-fos expression in the pineal gland and in the PVT after rTMS and light stimulation, respectively. Both stimulation modalities produce a strong reduction of c-fos expression in pinealocytes and a robust induction of c-fos expression in PVT neurons.

DISCUSSION

The patterns of immediate-early gene activation elicited by rTMS and ECS in rat brain are different. Most notably, rTMS results in strongly increased c-fos expression predominately in the PVT and specific cortical regions and moderate expression in regions controlling circadian rhythms. In contrast, ECS induces strong activation of c-fos expression in all cortical regions and hippocampus but weaker activation in the PVT and SCN (discussed below). It has been reported recently that GFAP transcripts are induced to a similar degree after rTMS and ECS in astrocytes located in the hippocampus (14). Our studies indicate that hippocampal neurons are affected minimally by rTMS. The discrepancy between these results can be explained by the different parameters of stimulation. GFAP mRNA expression is strongly induced after 10 trains of stimuli (10 sec, 25 Hz for a total of 2,500 pulses at 70% power), whereas c-fos expression is observable after a single stimulation with 50 pulses (2 sec, 25 Hz at 100% power). Fewer trains of stimuli are less effective in inducing GFAP expression (14). It is possible that the thresholds of activation of c-fos and GFAP mRNA expression differ. Thus, fewer pulses may induce c-fos expression in neurons but not GFAP in astrocytes. Whether a more robust stimulation with rTMS also leads to the activation of c-fos expression in astrocytes, or whether GFAP expression in astrocytes is regulated by neural activation, has not been determined. The size of the coil in relation to the size of the brain is critical when considering the effects of rTMS (discussed below). Therefore, seemingly similar conditions of stimulation may produce different patterns of gene expression in rats and in mice.

rTMS applied at different head locations produces essentially the same pattern of immediate-early gene expression. This property of rTMS is particularly difficult to explain for cortical regions. Although changing the position of the coil relative to the head should result in substantial variation of the magnetic field intensity acting on the same cortical regions (21), the patterns of neural stimulation remain unchanged. Also, cortical regions separated laterally only by few micrometers, and therefore exposed to virtually identical magnetic field intensities, display an all-or-none pattern of immediate-early gene induction. A possible explanation is that this activation may result secondarily from the stimulation of connecting neural circuits. Although this is likely for the cingulate cortex, since PVT neurons project to this region (32), the neural pathways responsible for the activation of other cortical regions by rTMS are not known. Another possibility is that neurons located in responsive cortical regions may be more susceptible to depolarization induced by electric current. If so, these neuronal populations would respond more readily to the currents induced by fluctuating magnetic fields. This hypothesis seems unlikely because the pattern of cortical activation after ECS is comparable throughout the cortex. Our results from the brain-slice experiments suggest that the PVT neurons may respond directly to fluctuating magnetic fields. Indirect stimulation of these neurons in vivo could result from the activation of interconnecting neural circuits or stimulation of afferent axonal tracts. This is probably not the case in brain slices because all but the local neural pathways are absent. The results of this analysis also confirm that the activation of the cortical regions by rTMS observed in vivo is indirect; stimulation of brain slices produces only a weak activation of cortical neurons, whereas the level of induction of c-fos mRNA expression observed in PVT neurons is comparable in vivo and in slices. PVT neurons receive synaptic input from the retina, which is also stimulated by rTMS. A component of the induction of c-fos mRNA expression in PVT neurons in vivo may be due to activation of retinal neurons. Taken together, our results suggest two hypotheses for the effects of rTMS on rat brain. (i) rTMS in rats acts primarily on the retina, a known low-threshold site for electromagnetic fields (33, 34), with induction of retinal phosphenes. Thus, consequent brain effects closely mimic those of natural light exposure. (ii) Neurons of the PVT are activated directly by the magnetic field, with secondary effects on other regions connected to it. In support of the first hypothesis are our results showing a response to rTMS in the retina, and the comparison between c-fos mRNA induction after rTMS or light exposure at night. However, the induction of c-fos mRNA in isolated brain slices and in blind rats, albeit at significantly lower levels than in control animals (data not shown), represent arguments against it.

Against the second hypothesis is the known biophysics of rTMS. Human experiments and extensive in vitro measurements on peripheral nerve suggest that magnetic stimulation activates neural elements indirectly, through induction of an electric field in the volume conductor. Depolarization occurs in myelinated axons at sites where the first derivative of the electric field is maximal, including branch points and bends (35, 36). However, the spatial distribution of the induced electric field makes stimulation of deep subcortical structures problematic. The electric field diminishes with depth, being forced to zero in the center of a sphere and highly constrained in the middle of a nonspherical target (37). Measurements in our model system corroborated this effect; the electric field experienced by the centrally located PVT is much smaller than that at the cortex. Activation of c-fos by preferential electric field stimulation of the PVT would seem highly improbable. Further, the efficiency of stimulation drops substantially when the size of the brain is much smaller than the size of the coil (a condition that is unavoidable when studying rTMS in small animals) (38). This unfavorable geometry probably accounts for the failure to elicit motor responses from rodents in our laboratory and most others, even when maximal stimulator output is used. In contrast, the retina, as a relatively superficial, low-threshold site, might be preferentially stimulated under these conditions. Direct stimulation of the PVT by rTMS in vivo would require either that PVT neurons are sensitive to much lower levels of the electric field or that they respond directly to the magnetic field, which is unaffected by passing through tissue. The influence of magnetic fields on circadian rhythms suggests that this may be a realistic possibility (33). We conclude that the response to rTMS observed in PVT neurons likely results from both direct and indirect activation.

ECT and rTMS affect behavior both in humans and in animals (12, 13, 39). The most likely interpretation of our results is that these two stimulations exert their effects by activating different brain regions. However, currents induced in the brain by ECT result in a relative weak activation of brain regions that are strongly activated by rTMS, such as the PVT. Accordingly, the behavioral and/or therapeutic effects of these two types of stimulation may involve weaker activation of common brain regions. In contrast to the widespread effects of ECS, rTMS may be more efficient in stimulating regions regulating specific behavioral responses. Thus, to produce equal effects with ECT, massive stimulation, which invariably induced seizures, is required. This is consistent with the observation that the induction of seizures seems to be essential for the antidepressant effects of ECT but not rTMS (5, 16, 40). In this context, activation of the PVT and SCN by rTMS is especially interesting; PVT neurons receive synaptic input from the retina, which plays a central role in circadian rhythm regulation, and project to the SCN, where the master circadian clock is located (24, 25, 41). Moreover, PVT and SCN neurons exhibit the highest density of melatonin binding sites in the brain (42, 43). Last, rTMS also induces c-fos expression in neurons of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, which, through the relay of sympathetic neurons, affect the pineal gland. In support of a hypothesis that rTMS affects circadian rhythms, our results show that rTMS administered during nighttime has the same effects on pinealocytes and PVT neurons as a brief exposure to light, which is known to reduce levels of melatonin (29, 30). The selective activation of regions controlling circadian rhythms by rTMS is consistent with reported links of circadian rhythms and major depression (44, 45); the duration of light/dark cycles influences seasonal depressive illnesses, possibly by resetting circadian rhythms, and participates in the effects of phototherapy (46). Also, patients suffering from major depression display a circadian variability in their symptomatic manifestations (47, 48). Although the different coil-to-brain ratio complicates the extrapolation of our finding to humans, our result suggests that rTMS might be particularly effective in the context of seasonal affective disorders and raise the question regarding the time of the day when rTMS may be applied to maximize its therapeutic effects.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Worley and David Linden for providing technical help with ECS and brain-slice preparations and Seth Blackshaw for the nonradioactive in situ hybridization experiments. We are particularly thankful to Solomon Snyder and David Linden for critically reviewing the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the E.A. & J. Klingenstein Fund (F.R.), from the Council for Tobacco Research (F.R.), and from the Swiss National Science Foundation (4038-044046 and 3231-044523.95 to T.E.S.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- rTMS

repetitive magnetic stimulation

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- ECT

electroconvulsive therapy

- ECS

electroconvulsive stimulation

- PVT

paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus

- SCN

suprachiasmatic nucleus

- CREB

cAMP response element binding protein

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

References

- 1.Walsh V. Curr Biol. 1998;8:R8–R11. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.George M S, Wassermann E M, Post R M. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;8:373–382. doi: 10.1176/jnp.8.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.George M S, Wassermann E M. Convuls Ther. 1994;10:251–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belmaker R H, Fleischmann A. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38:419–421. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)92243-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pascual-Leone A, Rubio B, Pallardo F, Catala M D. Lancet. 1996;348:233–237. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)01219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pascual-Leone A, Gomez-Tortosa E, Grafman J, Alway D, Nichelli P, Hallett M. Neurology. 1994;44:892–898. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.3_part_1.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen L G, Celnik P, Pascual-Leone A, Corwell B, Falz L, Dambrosia J, Honda M, Sadato N, Gerloff C, Catala M D, Hallett M. Nature (London) 1997;389:180–183. doi: 10.1038/38278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen R, Gerloff C, Hallett M, Cohen L G. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:247–254. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.George M S, Wassermann E M, Williams W A, Callahan A, Ketter T A, Basser P, Hallett M, Post R M. NeuroReport. 1995;6:1853–1856. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199510020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dearing J G M, Greenberg B D, Wassermann E M, Schlaepfer T E, Murphy D L, Hallet M, Post R M. CNS Spectrums. 1997;2:53–68. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkcaldie M T, Pridmore S A, Pascual-Leone A. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997;31:264–272. doi: 10.3109/00048679709073830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleischmann A, Prolov K, Abarbanel J, Belmaker R H. Brain Res. 1995;699:130–132. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01018-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zyss T. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;42:920–924. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00518-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujiki M, Steward O. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;44:301–308. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zyss T. Med Hypotheses. 1994;43:69–74. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(94)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan A, Mirolo M H, Hughes D, Bierut L. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1993;16:497–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newman M E, Lerer B. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1989;13:1–30. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(89)90002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pascual-Leone A, Valls-Sole J, Wassermann E M, Hallett M. Brain. 1994;117:847–858. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.4.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole A J, Abu-Shakra S, Saffen D W, Baraban J M, Worley F. J Neurochem. 1990;55:1920–1927. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb05777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swinyard E A. In: Experimental Models of Epilepsy. Purpura D P, Penry J K, Tower D, Woodbury D M, Walter R, editors. New York: Raven; 1972. pp. 433–458. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weissman J D, Epstein C M, Davey K R. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1992;85:215–219. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(92)90135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji R R, Zhang X, Zhang Q, Dagerlind A, Nilsson S, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, Hökfelt T. Neuroscience. 1995;68:563–576. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)94333-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji R R, Rupp F. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1776–1785. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-05-01776.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moga M M, Weis R, Moore R Y. J Comp Neurol. 1995;359:221–238. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pauly J E. Am J Anat. 1983;168:365–388. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001680403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoeffler J P, Meyer T E, Yun Y, Jameson J L, Habener J F. Science. 1988;242:1430–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.2974179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ginty D D, Kornhauser J M, Thompson M A, Bading H, Mayo K E, Takahashi J S, Greenberg M E. Science. 1993;260:238–241. doi: 10.1126/science.8097062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ginty D D, Bonni A, Greenberg M E. Cell. 1994;77:713–725. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Axelrod J. Science. 1974;184:1341–1348. doi: 10.1126/science.184.4144.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cassone V M, Warren W S, Brooks D S, Lu J. J Biol Rhythms. 1993;8:S73–S81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida K, Kawamura K, Imaki J. Neuron. 1993;10:1049–1054. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90053-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berendse H W, Groenewegen H J. Neuroscience. 1991;42:73–102. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90151-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reiter R J. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 1992;15:226–244. doi: 10.1016/0273-2300(92)90035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olcese J, Reuss S, Stehle J, Steinlechner S, Vollrath L. Brain Res. 1988;448:325–330. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barker A T, Garnham C W, Freeston I L. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Suppl. 1991;43:227–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maccabee J, Amassian V E, Eberle L, Cracco R Q. J Physiol. 1993;460:201–219. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tofts S. Phys Med Biol. 1990;35:1119–1128. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/35/8/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen D, Cuffin B N. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1991;8:102–111. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199101000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kellar K J. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;20:30–34. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1017070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pascual-Leone A, Houser C M, Reese K, Shotland L I, Grafman J, Sato S, Valls-Sole J, Brasil-Neto J P, Wassermann E M, Cohen L G, et al. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1993;89:120–130. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(93)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Florez J C, Takahashi J S. Ann Med. 1995;27:481–490. doi: 10.3109/07853899709002457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Recio J, Pevet P, Vivien-Roels B, Miguez J M, Masson-Pevet M. J Biol Rhythms. 1996;11:325–332. doi: 10.1177/074873049601100406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reppert S M, Weaver D R, Ebisawa T. Neuron. 1994;13:1177–1185. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hawkins L. Endeavour. 1992;16:122–127. doi: 10.1016/0160-9327(92)90070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown G M. Horm Res. 1992;3:105–111. doi: 10.1159/000182410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dalgleish T, Rosen K, Marks M. Br J Clin Psychol. 1996;35:163–182. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1996.tb01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neylan T C. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;2:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dijk D J, Boulos Z, Eastman C I, Lewy A J, Campbell S S, Terman M. J Biol Rhythms. 1995;10:113–125. doi: 10.1177/074873049501000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paxinos G, Watson C, editors. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego: Academic; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]