Abstract

Tissue engineering strategies have the potential to improve upon current techniques for intervertebral disc repair. However, determining a suitable biomaterial scaffold for disc regeneration is difficult due to the complex fibrocartilaginous structure of the tissue. In this study, cells isolated from three distinct regions of the intervertebral disc, the outer and inner annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus, were expanded and seeded on resorbable polyester fiber meshes and encapsulated in calcium crosslinked alginate hydrogels, both chosen to approximate the native tissue architecture. Three-dimensional (3D) constructs were cultured for 14 days in vitro and evaluated histologically and quantitatively for gene expression and production of types I and II collagen and proteoglycans. During monolayer expansion, the cell populations maintained their distinct phenotypic morphology and gene expression profiles. However, after 14 days in 3D culture, there were no significant differences in morphology, gene expression, or protein production between all three cell populations grown in either alginate or polyester fiber meshes. The results of this study indicate that the culture environment may have a greater impact on cellular behavior than the intrinsic origin of the cells, and suggest that only a single-cell type may be required for intervertebral disc regenerative therapies.

Introduction

The intervertebral disc is a fibrocartilaginous tissue that confers flexibility to the spine by allowing limited bending and twisting movements between vertebral bodies. The pathologic conditions that give rise to disc failure (i.e., trauma and degeneration) have been implicated as a source of chronic lower back pain, a health care problem with an estimated cost reaching $90.7 billion annually.1 A variety of procedures have been developed to treat ailments related to disc failure. For severe cases, surgical intervention is required. These procedures often involve removal of degenerate tissue or surgical stabilization, which result in loss of motion, abnormally excessive local stresses at the surgical site, and ultimately fail to treat the underlying disease state.2,3 Tissue engineering methodologies to fabricate biohybrid constructs provide a promising alternative for intervertebral disc repair.

Strategies for engineering the intervertebral disc are complicated by the complex fibrocartilaginous nature of the tissue. The disc is a composite structure consisting of the lamellar annulus fibrosus comprised of organized collagen fibers arranged concentrically around the cartilaginous, semifluid nucleus pulposus (NP).4 The biochemical composition of the intervertebral disc displays much variation among the different regions of the tissue. The outer annulus fibrosus (OA) is rich in type I collagen, consistent with fibrous, load-bearing tissues in tension.4–6 Conversely, the NP contains large amounts of aggregating proteoglycans (i.e., aggrecan) and type II collagen, typical of compression-resisting tissues.5–7 The inner annulus fibrosus (IA) represents a transitional zone and contains greater amounts of type II collagen and aggrecan than the OA as it is subjected to compressive loads transferred from the NP. Hence, the compositional gradient that extends from the OA to the NP is directly tied to the mechanical loads experienced at the specific anatomical sites.8 Moreover, the biomechanical properties of the intervertebral disc are dependent on the continued biosynthetic activity of disc cells in response to these loads.9

Cells isolated from the three distinct regions of the disc also show differences in morphology and extracellular matrix (ECM) production. In monolayer culture, OA cells are fibroblastic, while IA cells are more polygonal and produce a fibrocartilaginous ECM with greater quantities of type II collagen in comparison to OA cells.10,11 NP cells display a rounded, chondrocyte-like morphology and secrete ECM macromolecules more consistent with hyaline cartilage.10,11 The characteristic phenotype of the different intervertebral disc cell populations can be modulated by environmental conditions, such as serial expansion in monolayer culture, supplementation with growth factors, application of mechanical stimulation, or cultivation in three-dimensional (3D) scaffolds.11–23

Traditionally, biomaterial scaffolds for tissue engineering applications have been selected based on similarities with the native tissue architecture. For example, cells from cartilaginous tissues are often encapsulated in hydrogels composed of polysaccharides such as alginate or agarose, which maintain the characteristic spherical cell shape.13,24,25 Cells from oriented, collagenous tissues (i.e., tendons and ligaments) are routinely cultured on aligned fibrous scaffolds fabricated from synthetic or natural polymers, including resorbable polyesters or collagen.26–30 Similarities between the chosen scaffold and the native tissue allow cells to retain their characteristic cellular morphology, which has been shown to be important for maintaining the cellular phenotype.31–35 Moreover, such materials promote the expression of ECM macromolecules typically found in the respective tissues. Although hydrogels and fibrous meshes have been investigated for 3D culture of intervertebral disc cells, no previous studies have specifically examined the behavior of cells from all three regions of the disc (i.e., OA, IA, and NP) to determine which substrate is more suitable for maintaining the distinct phenotypes of the different intervertebral disc cell populations.14,36–41 Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the gene expression profile and protein elaboration of types I and II collagen and sulfated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) of the separate intervertebral disc cell types within 3D materials that mimic the native intervertebral disc tissue architecture—encapsulated within alginate hydrogels and seeded on resorbable polyester fiber meshes. We hypothesized that alginate hydrogels would be more conducive to maintaining the phenotype of IA and NP cells, while polyester fiber meshes would promote the OA phenotype, due to structural similarities between the biomaterial scaffolds and the native tissue.

Materials and Methods

Primary cell isolation

All cell culture supplies were purchased from Gibco-Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) unless otherwise noted. Adult bovine tails were obtained from a local abattoir and caudal disc tissue was excised from levels C2–C4 in a sterile environment. The OA, IA, and NP were separated through gross visual inspection. The determination between OA and IA was based on the amount of hydrated ground substance between the lamellae. Each tissue was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT), 2.5 μg/mL fungizone reagent, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.075% sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) (primary media) for 1 day at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% carbon dioxide (CO2) to confirm that no contamination occurred during the harvesting process. Tissue was diced and cells from each region were released through enzymatic digestion with 7000 units collagenase type IV (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) per gram of tissue at 37°C. Tissue digestions were incubated until tissue was fully digested, typically 2 h for NP, 4 h for IA, and 5 h for OA. All enzymes were prepared in primary medium. Released cells were designated passage 0 (P0).

Serial monolayer passaging

Cells were plated at a concentration of 4 × 106 cells/150 cm2 on tissue culture–treated polystyrene dishes. At each passage (P0–P2), cells were evaluated for cellular morphology and gene expression. Cell morphology was assessed using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted phase contrast microscope and AxioVision image capturing software. RNA from monolayer cultures was isolated by guanidium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction using the TRIZOL isolation system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) was performed as detailed below. All cultures (P0–P2) were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.075% NaHCO3 in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C and 5% CO2. At passage 2, cells were then encapsulated within alginate hydrogels or seeded on polyester fiber meshes.

Alginate hydrogel preparation and cell encapsulation

A 1.6% solution of a high guluronate to mannuronate ratio ultrapure alginate (MVG) (Pronova UP; FMC Biopolymer, Norway) in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) was prepared and sterilized using a 0.45-μm syringe filter. Cells were resuspended in sterile DPBS prior to addition of 1.6% MVG to form a final concentration of 5 × 106 cells/mL of 1.2% MVG. Approximately 150 μL was cast into a custom-designed gel casting device between two sheets of filter paper soaked in 102 mM calcium chloride (CaCl2). After 10 min, the top of the cast was removed and submerged in a 102 mM CaCl2 bath for an additional 10 min. Calcium crosslinked cell-seeded alginate hydrogels were removed and incubated in DMEM with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.075% NaHCO3 (growth media) at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. At day 1, medium was replaced with vitamin C (50 μg/mL)–supplemented growth media and exchanged every 2–3 days.

Polyester fiber mesh preparation and cell seeding

A 1.1-mm thick nonwoven poly(glycolic acid) (PGA) fiber mesh (Biomedical Structures LLC, Slatersville, RI) was reinforced with a 3% solution of 50 kDa poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA) (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) dissolved in chloroform through a solvent evaporation process.42 Reinforced polymer was fashioned into 2.5 cm × 0.5 cm strips and sequentially pretreated with 1 N sodium hydroxide (NaOH), distilled water, and 100% ethanol for 4 min per treatment. Prior to cell seeding, strips were treated for approximately 16 h in 70% ethanol to further increase surface wettability and promote cellular attachment. Scaffolds were UV sterilized and secured into custom-designed clamps. Five million cells were seeded per strip and allowed to adhere for 30 min at 37°C. Cell-seeded polyester fiber mesh clamps were then flooded with 60 mL of growth medium. At day 1, medium was replaced with vitamin C (50 μg/mL)–supplemented growth medium and exchanged every 2–3 days.

Gene expression

At days 3, 7, and 14, RNA was isolated from cell-seeded constructs for gene expression evaluation. For alginate hydrogels, cells were released from the hydrogel by addition of 55 mM sodium citrate and 35 mM EDTA in 0.15 M NaCl, pH 6.8 (1 mL per two hydrogels), and incubated on an orbital shaker until the alginate was fully dissolved (approximately 15 min). Cells were pelleted by centrifugation (2000 rcf, 5 min), and the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used to extract and purify RNA from the cell pellets. RNA from polyester fiber meshes was isolated by guanidium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction using the TRIZOL isolation system (Invitrogen). Purity of all RNA samples (passage 0–2 monolayer, alginate hydrogels, and polyester fiber meshes) was assessed spectrophotometrically. RT was performed using the Superscript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen) using oligo(dT) primers at 42°C for 50 min to isolate and amplify mRNA. Real-time PCR was conducted using the SYBR Green Master Mix Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on an ABI PRISM 7000 using 0.25 μg of RT product. Primers for collagen type I, collagen type II, aggrecan, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) are as published.43 Types I and II collagen and aggrecan gene expression were normalized to GAPDH expression, and fold differences were calculated using the ΔΔCt method.

Collagen quantification

Protein expression of types I and II collagen was quantified using an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA). ELISA samples were isolated and stored in 0.05 N acetic acid (pH 2.8) at −20°C prior to processing. Polyester fiber mesh samples were cut and placed in 300 μL of 0.05 N acetic acid (pH 2.8). Cells encapsulated in alginate hydrogels were released using 55 mM sodium citrate and 35 mM EDTA in 0.15 M NaCl, pH 6.8, as for RNA isolation and stored in 300 μL of 0.05 N acetic acid at −20°C. To extract proteins, all samples were removed from acetic acid and treated with 500 μL of 3 M guanidine HCl/0.05 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, (GuHCl) for 16 h rotating at 4°C. GuHCl supernatant was removed and extracted protein was quantified by ELISA. Remaining cell pellets/samples were washed twice with 800 μL cold sterile water and treated with 525 μL of 2 mg/mL pepsin in 0.05 N acetic acid for 48 h rotating at 4°C. After 48 h, pepsin was neutralized by addition of 100 μL of 10× TBS and 25 μL of 1 N NaOH. Pepsin and GuHCl digests were plated in a 96-well Nunc Maxisorp plate for collagen protein quantification. One hundred microliters of 1:1 ratio of digest (GuHCl or pepsin) to coating buffer (15 mM sodium carbonate, 35 mM NaHCO3, and 3 mM sodium azide) was plated per sample. Monoclonal antibodies to types I (1:10,000) (Sigma) and II (1:100 dilution of supernatant) (II-II6B3; DSHB, Iowa City, IA) collagen were used. A peroxidase-based detection system using biotinylated secondary antibody (anti-mouse IgG/anti-rabbit IgG H + L; Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) and a streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase enzyme conjugate (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were used. One hundred microliters of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine as the substrate chromagen was allowed to react for 4 min and then stopped with 50 μL of 1 N H2SO4. Total reacted substrate was spectrophotometrically analyzed at 450 nm using a Bio-Tek Synergy-HT microplate reader (Winooski, Vermont), and total protein was determined from standard curves of bovine type I collagen (isolated from bovine placenta; Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA) and bovine type II collagen (isolated from bovine nasal cartilage; Rockland).

Sulfated GAG quantification

Production of sulfated GAGs was quantified using the 1,9-dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) dye-binding assay.44 Protein-extracted samples (pepsin and GuHCl digests) were allowed to react with DMMB at pH 3.5 (Sigma) and spectrophotometrically analyzed at 525 nm using a Bio-Tek Synergy-HT microplate reader (Winooski, Vermont). Total GAG was determined from standard curves of chondroitin-6-sulfate C isolated from shark cartilage (Sigma).

Total DNA quantification

Total DNA (pepsin and GuHCl digests) was determined using the PicoGreen dsDNA assay (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).45 After ELISA and DMMB quantification of protein, pepsin and GuHCl digests were incubated with 0.5% Triton-X and cells were lysed and homogenized with repeated pipeting and freeze-thaw cycles. One hundred microliters of PicoGreen reagent was mixed with 100 μL of diluted sample in a 96-well fluorescence microplate. The plate was read at 480 nm excitation and 520 nm emission. DNA values were determined from a calf thymus DNA standard curve. Total DNA values were used to normalize the biochemistry data (collagen ELISA and DMMB assay).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Protein deposition was visualized by immunohistochemistry of 3D cultures. Alginate hydrogels were treated with 100 mM BaCl2 for 15 min and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4°C. Polyester fiber meshes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 h at 4°C. All samples were paraffin embedded, sectioned using a Lieca microtome (Model 2030, Nussloch, Germany), and processed for immunohistochemistry. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was used to assess cellular morphology within the 3D cultures. For collagen immunohistochemistry, samples were pretreated with hyaluronidase for 30 min and 0.5 N acetic acid for 2 h. Samples for chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan immunohistochemistry were only treated with 0.5 N acetic acid for 2 h. Monoclonal antibodies to types I (1:200) (Sigma) and II (1:3 dilution of supernatant) (II-II6B3; DSHB) collagen and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (1:100) (Sigma) were used. A peroxidase-based detection system (Vectastain Elite ABC; Vector Labs) and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as the substrate chromagen were used to detect protein localization. Nonimmune controls were included without primary antibody. Stained cultures were viewed with a Zeiss Axioskop 40 optical microscope and images were captured using AxioVision software.

Statistical analysis

Gene expression and protein accumulation (ELISAs and DMMB assay) were examined for statistical significance using a two-way ANOVA (time and cell type) within each culture condition (polyester fiber mesh and alginate hydrogel) with a Tukey post hoc test and significance set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Characterization of intervertebral disc cells in two-dimensional monolayer culture

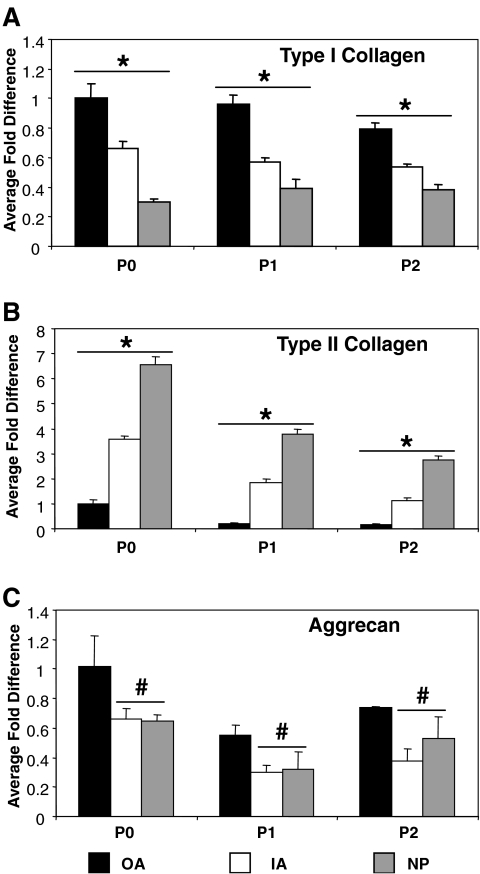

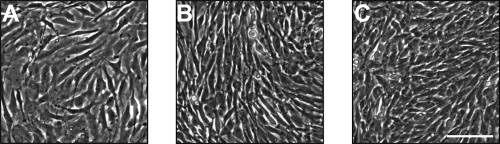

Primary cultures of intervertebral disc cells up to passage 2 (5–8 population doublings) showed distinct differences in both cellular morphology and gene expression of characteristic proteins. In general, gene expression decreased with passage for all proteins and all cell types (Fig. 1). Both types I and II collagen displayed a significant difference in gene expression between all cell types at each passage (Fig. 1A, B). As expected, OA cells exhibited the greatest expression of type I collagen, and NP cells exhibited the greatest expression of type II collagen. Aggrecan gene expression did not follow a similar trend as the collagens, with IA and NP cell types showing similar expression profiles that were significantly less than OA expression at all passages (Fig. 1C). Gene expression differences were mirrored by distinct differences in cell shape (Fig. 2). At passage 2, cells of the annulus, both OA and IA, exhibited a fibroblastic morphology, with cells of the OA larger in size than those of the IA (Fig. 2A, B). However, cells isolated from the NP were more polygonal in shape and much smaller than the cells of the annulus fibrosus (Fig. 2C). Overall, at passage 2, the cell populations of the bovine intervertebral disc maintained distinct differences with respect to both cellular morphology and gene expression profiles.

FIG. 1.

Gene expression profile of intervertebral disc cells in two-dimensional culture. Quantitative PCR analysis of type I collagen (A), type II collagen (B), and aggrecan (C) for sequential monolayer passages of IVD cells. Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference between all cell types within passage. # indicates significant difference compared to OA cells within passage.

FIG. 2.

Morphology of intervertebral disc cells in two-dimensional (2D) culture. Passage 2 OA (A), IA (B), and NP (C) cells on 2D tissue culture polystyrene. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Gene expression analysis of intervertebral disc cells in 3D culture

In alginate hydrogels, gene expression of all analyzed ECM macromolecules (types I and II collagen and aggrecan) decreased for all cell types over the 14-day culture period (Fig. 3A, C, and E). Additionally, there was no significant difference in expression based on cell type for all genes at day 14. At the early time points (D3 and D7), IA alginate cultures exhibited increased type I collagen and aggrecan expression compared to OA and NP cultures, while type II collagen was expressed at higher levels in NP cultures (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Gene expression analysis of intervertebral disc cells in 3D culture. Quantitative PCR analysis of type I collagen (A, B), type II collagen (C, D), and aggrecan (E, F) in alginate (A, C, E) and polyester fiber mesh scaffolds (B, D, F). Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference versus all other time points within cell type. ▲indicates significant difference versus D14 within cell type. # indicates significant difference compared to all other cell types within time point. † indicates significant difference versus NP cultures within time point. ‡ indicates significant difference compared to IA cultures within time point.

In polyester fiber mesh cultures, no consistent trend in gene expression between cell types was observed for all ECM components. By day 14, there was no significant difference in expression of types I and II collagen between cell types, similar to alginate cultures. Type I collagen expression by OA and NP cultures did not significantly change throughout the culture period, and IA cultures exhibited peak expression at day 7 (Fig. 3B). Type II collagen expression by IA and NP cultures steadily decreased, and OA cultures exhibited no significant changes over the 14-day culture period (Fig. 3D). Aggrecan gene expression significantly decreased over time with IA cultures exhibiting increased expression compared to both OA and NP cultures (Fig. 3F).

Biochemical analysis of intervertebral disc cells in 3D culture

In alginate hydrogels, type I collagen production (normalized to DNA) remained constant (∼0.46 ± 0.16 ng/μg DNA) throughout the 14-day culture period, and there was no significant effect of time or cell type (Fig. 4A). Normalized type II collagen expression increased after 3 days of culture with peak expression occurring at day 7 with no significant effect of cell type (Fig. 4C). Normalized GAG expression also remained constant (∼6.12 ± 1.26 μg/μg DNA) throughout the 14-day culture period with no significant effect of time or cell type (Fig. 4E). Total DNA per scaffold in alginate cultures remained constant at 19.3 ± 2.76 μg DNA (Fig. 4G). Overall, there were no consistent trends in ECM production between cell types.

FIG. 4.

Biochemical analysis of intervertebral disc cells in 3D culture. Total type I collagen protein expression (A, B), type II collagen (C, D), GAGs (E, F), and DNA (G, H) in alginate (A, C, E, G) and polyester fiber mesh scaffolds (B, D, F, H). Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference versus all other time points within cell type. $ indicates significant difference compared to D7 within cell type. ▲indicates significant difference versus D14 within cell type. # indicates significant difference versus all other cell types within time point. † indicates significant difference compared to NP cultures within time point.

In polyester fiber mesh cultures, normalized type I collagen expression remained constant (∼1.26 ± 1.05 ng/μg DNA) throughout the 14-day culture period with no significant effect of time or cell type (Fig. 4B). Normalized type II collagen expression increased after 3 days of culture with peak expression occurring at day 7, similar to the trend found in alginate cultures (Fig. 4D). Normalized GAG content remained constant throughout the 14-day culture period (∼1.45 ± 0.35 μg/μg DNA) with no significant effect of time or cell type (Fig. 4F). Total DNA significantly increased over time, with OA cultures exhibiting the greatest increase in cell numbers (Fig. 4H). Despite differences in DNA content, there was no consistent significant difference in ECM production between intervertebral disc cell types.

Histological and immunohistochemical characterization of intervertebral disc cells in 3D culture

Intervertebral disc cells were homogenously distributed throughout the alginate hydrogels and maintained a rounded morphology (Fig. 5A–C). However, in polyester fiber mesh scaffolds, the cells infiltrated into the interior of the polymer and maintained an elongated, fibroblast-like morphology (Fig. 5D–F). Immunohistochemical staining of collagens and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan showed matrix macromolecules secreted pericellularly in alginate hydrogels and throughout the scaffold for polyester fiber meshes (not shown). In addition, hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed no distinct differences in cell morphology and organization between the three intervertebral disc cell types in either alginate hydrogels or polyester fiber mesh scaffolds.

FIG. 5.

Histological analysis of intervertebral disc cells in 3D culture. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of day 14 alginate (A–C) and polyester fiber mesh (D–F) OA (A, D), IA (B, E), and NP (C, F) cultures. Scale bar = 25 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Discussion

In this study, the gene expression and ECM elaboration profiles of the three distinct cell populations of the bovine intervertebral disc were evaluated in 3D culture formats that simulate the structures of the native tissue. Encapsulation within alginate hydrogels was employed to mimic the gel-like environment of the NP, while reinforced polyester fiber meshes were used to approximate the fibrous structure of the annulus fibrosus. Both alginate hydrogels and resorbable polyester fiber meshes comprised of PGA and PLLA are FDA approved and have been investigated previously in a composite biohybrid intervertebral disc construct with positive results; however, the behavior of all three disc cell types in these materials has not been investigated previously.14,36–41 Prior to seeding in 3D culture, cells of the OA, IA, and NP exhibited distinct morphological and gene expression characteristics indicative of the specialized phenotypes observed in native disc tissue (Figs. 1 and 2). We hypothesized that these differences would be maintained in 3D culture, with the alginate hydrogels more conducive to promoting the NP cellular phenotype and the polyester fiber meshes actively supporting the differentiated phenotype of OA and IA cells. However, the results of this study demonstrate that the individual populations of the intervertebral disc do not maintain their phenotype in 3D culture. Rather, the specific gene expression and protein elaboration patterns appear to be largely dictated by the culture environment rather than the intrinsic origin of the cells. By 14 days, all three cell types encapsulated in alginate hydrogels displayed a rounded, chondrocyte-like morphology, expressing high levels of type II collagen versus type I collagen and accumulation of sulfated GAGs. On the polyester fiber meshes, the three disc cell populations exhibited a fibroblast-like cell shape and produced greater amounts of both types I and II collagen in comparison to sulfated GAGs. Overall, after 2 weeks in culture, there were no significant differences in gene expression or protein production between all three cell populations in either material.

Several studies have characterized the phenotypic response of intervertebral disc cells on different substrates. For example, porcine IA and OA cells have been shown to undergo a reversible shift in gene expression levels in monolayer culture in comparison to alginate.11 A similar effect has been observed in bovine disc cells, with IA, OA, and NP cells exhibiting enhanced proteoglycan biosynthesis in alginate or collagen gels in contrast to cells in monolayer.10 In a related study, human annulus cells exhibited the most extensive ECM production when cultured in collagen sponges in comparison to a variety of materials, including agarose, alginate, fibrin, and collagen gels.39 Taken together, these prior studies underscore the important influence of biomaterial scaffolds on intervertebral disc cell phenotype. Our findings support the pivotal role of culture microenvironment on disc cell behavior, and further suggest that the inherent differences between the cell types may become less distinct with time on 3D scaffolds.

There are considerable differences between the alginate hydrogels and the polyester fiber scaffolds used in this study; therefore, caution must be used when making direct comparisons between the two culture conditions. These differences include surface chemistry, surface topography, stiffness, and permeability, all of which may modulate the cellular response to varying degrees. As such, rather than comparing which 3D environment is more suitable for intervertebral disc regeneration, the main objective of this study was to determine whether the distinct phenotypes of the specific intervertebral disc cell populations could be maintained in 3D culture conditions that mimic the native environment. Nevertheless, it is possible to make some general conclusions regarding the differential cellular response between the two materials. Based on DNA measurements, the cells did not proliferate in the alginate hydrogels, as the values remained constant for all three cell types over the entire culture period. In contrast, the disc cells in the polyester fiber scaffolds appeared to divide over time, which was most evident in annulus cell-seeded constructs. Also, the sulfated GAG content of the alginate hydrogels was significantly greater than that observed for the polyester fiber meshes. Specific reasons for the difference in GAG content cannot be determined from this experiment due to the multiple variables that exist between the two scaffolds. It is possible that the fibrous mesh did not allow for retention of the synthesized GAGs, a finding that has been reported for articular chondrocytes seeded in similar resorbable fiber meshes.46 However, since the culture medium was not assayed for GAG (or collagen) content in this study, it is not clear whether the matrix macromolecules were actually lost from the scaffolds or secreted at lower levels by the seeded cells. A result common to both materials was the significant reduction in gene expression for the various ECM components by all cell types over time. This may be due to the cells achieving homeostasis following an early adjustment period after placement in the 3D constructs. By the first week of culture, the cells may have acclimated, thereby reducing the requirement for transcription of newly synthesized matrix.

The major conclusion of this study is that distinct cell populations of the intervertebral disc adopt similar phenotypes when cultured in 3D scaffolds, exhibiting identical cell morphologies and gene and protein expression profiles that are not significantly different from one another. These results may have a direct impact on engineering approaches for intervertebral disc repair, as they indicate that only a single disc cell type may be required to regenerate all three regions of the tissue. Our findings are supported by a related study that demonstrated that annulus fibrosus and NP cells exhibited similar ECM deposition profiles when seeded on collagen/hyaluronan scaffolds. As such, the authors suggested that disc repair may not be limited by the availability of “authentic” nucleus cells, which are difficult to expand in culture.47 Additionally, our results may have broader implications on tissue engineering strategies by suggesting that the culture environment (i.e., 3D substrate, soluble signaling factors, biophysical regulators, etc.) is more important than the intrinsic origin of the cells in determining the properties of the engineered construct. The application of select growth factors or mechanical stimulation may still be necessary to maintain the phenotype of specific intervertebral disc cell types, regardless of the biomaterial scaffold.15–20,22,23,48 Future studies will focus on examining environmental cues required for the assembly of mechanically functional extracellular matrix by the different intervertebral disc cell populations in 3D culture formats.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant EB002425 and a National Science Foundation graduate fellowship (A.R.). The II-II6B3 antibody developed by TF Linsenmayer was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by the University of Iowa, Department of Biological Sciences, Iowa City, IA 52242.

References

- 1.Luo X. Pietrobon R. Sun S. Liu G. Hey L. Estimates and patterns of direct health care expenditures among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine. 2004;29:79. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000105527.13866.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An H. Boden S.D. Kang J. Sandhu H.S. Abdu W. Weinstein J. Summary statement: emerging techniques for treatment of degenerative lumbar disc disease. Spine. 2003;28:S24. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000076894.33269.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang R. Tropiano P. Marnay T. Girardi F. Lim M. Cammisa F.J. Range of motion and adjacent level degeneration after lumbar total disc replacement. Spine J. 2006;6:242. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marchand F. Ahmed A.M. Investigation of the laminate structure of lumbar disc anulus fibrosus. Spine. 1990;15:402. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199005000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antoniou J. Steffen T. Nelson F. Winterbottom N. Hollander A. Poole R. Aebi M. Alini M. The human lumbar intervertebral disc: evidence for changes in the biosynthesis and denaturation of the extracellular matrix with growth, maturation, ageing, and degeneration. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:996. doi: 10.1172/JCI118884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bayliss M.T. Johnstone B. O'Brien J.P. Proteoglycan synthesis in the human intervertebral disc; variation with age, region and pathology. Spine. 1988;13:972. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198809000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oegema T.R. Biochemistry of the intervertebral disc. Clin Sports Med. 1993;12:419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urban J.P.G. The effect of physical factors on disk cell metabolism. In: Buckwalter J.A., editor; Goldberg V.M., editor; Woo S.L.Y., editor. Musculoskeletal Soft-Tissue Aging: Impact on Mobility. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1993. pp. 391–412. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guilak F. Ting-Beall H. Baer A. Trickey W. Erickson G. Setton L. Viscoelastic properties of intervertebral disc cells. Identification of two biomechanically distinct cell populations. Spine. 1999;24:2475. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199912010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horner H.A. Roberts S. Bielby R.C. Menage J. Evans H. Urban J.P. Cells from different regions of the intervertebral disc: effect of culture system on matrix expression and cell phenotype. Spine. 2002;27:1018. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200205150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J.Y. Baer A.E. Kraus V.B. Setton L.A. Intervertebral disc cells exhibit differences in gene expression in alginate and monolayer culture. Spine. 2001;26:1747. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200108150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chou A. Bansal A. Miller G. Nicoll S. The effect of serial monolayer passaging on the collagen expression profile of outer and inner anulus fibrosus cells. Spine. 2006;31:1875. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000229222.98051.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gruber H.E. Hanley E.N. Human disc cells in monolayer vs 3D culture: cell shape, division and matrix formation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2000;1:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruber H.E. Stasky A.A. Hanley E.N. Characterization and phenotypic stability of human disc cells in vitro. Matrix Biol. 1997;16:285. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(97)90016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hutton W. Elmer W. Boden S. Hyon S. Toribatake Y. Tomita K. Hair G. The effect of hydrostatic pressure on intervertebral disc metabolism. Spine. 1999;24:1507. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199908010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rannou F. Poiraudeau S. Foltz V. Boiteux M. Corvol M. Revel M. Monolayer anulus fibrosus cell cultures in a mechanically active environment: local culture condition adaptations and cell phenotype study. J Lab Clin Med. 2000;136:412. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2000.109755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutton W.C. Elmer W.A. Bryce L.M. Kozlowska E.E. Boden S.D. Kozlowski M. Do the intervertebral disc cells respond to different levels of hydrostatic pressure? Clin Biomech. 2001;16:728. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai T. Guttapalli A. Oguz E. Chen L. Vaccaro A. Albert T. Shapiro I. Risbud M. Fibroblast growth factor-2 maintains the differentiation potential of nucleus pulposus cells in vitro: implications for cell-based transplantation therapy. Spine. 2007;32:495. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000257341.88880.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasra M. Goel V. Martin J. Wang S.-T. Choi W. Buckwalter J. Effect of dynamic hydrostatic pressure on rabbit intervertebral disc cells. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:597. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim D. Moon S. Kim H. Kwon U. Park M. Han K. Hahn S. Lee H. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 facilitates expression of chondrogenic, not osteogenic, phenotype of human intervertebral disc cells. Spine. 2003;28:2679. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000101445.46487.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tim Yoon S. Su Kim K. Li J. Soo Park J. Akamaru T. Elmer W. Hutton W. The effect of bone morphogenetic protein-2 on rat intervertebral disc cells in vitro. Spine. 2003;28:1773. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000083204.44190.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neidlinger-Wilke C. Wurtz K. Urban J. Borm W. Arand M. Ignatius A. Wilke H.-J. Claes L.E. Regulation of gene expression in intervertebral disc cells by low and high hydrostatic pressure. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:372. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0112-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reza A. Nicoll S. Hydrostatic pressure differentially regulates outer and inner annulus fibrosus cell matrix production in 3D scaffolds. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36:204. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9407-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiba K. Andersson G.B. Masuda K. Thonar E.J. Metabolism of the extracellular matrix formed by intervertebral disc cells cultured in alginate. Spine. 1997;22:2885. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199712150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo J. Jourdian G. MacCallum D. Culture and growth characteristics of chondrocytes encapsulated in alginate beads. Connect Tissue Res. 1989;19:277. doi: 10.3109/03008208909043901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao Y. Vacanti J. Ma X. Paige K. Upton J. Chowanski Z. Schloo B. Langer R. Vacanti C. Generation of neo-tendon using synthetic polymers seeded with tenocytes. Transplant Proc. 1994;26:3390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aoki M. Miyamoto S. Okamura K. Yamashita T. Ikada Y. Matsuda S. Tensile properties and biological response of poly(L-lactic acid) felt graft: an experimental trial for rotator-cuff reconstruction. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2004;71:252. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao D. Liu W. Wei X. Xu F. Cui L. Cao Y. In vitro tendon engineering with avian tenocytes and polyglycolic acids: a preliminary report. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1369. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caruso A.B. Dunn M.G. Changes in mechanical properties and cellularity during long-term culture of collagen fiber ACL reconstruction scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;73A:388. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee C.H. Shin H.J. Cho I.H. Kang Y.-M. Kim I.A. Park K.-D. Shin J.-W. Nanofiber alignment and direction of mechanical strain affect the ECM production of human ACL fibroblast. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1261. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benya P.D. Shaffer J.D. Dedifferentiated chondrocytes reexpress the differentiated collagen phenotype when cultured in agarose gels. Cell. 1982;30:215. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benya P.D. Padilla S.R. Nimni N.E. Independent regulation of collagen types by chondrocytes during the loss of differentiated function in culture. Cell. 1978;15:1313. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Von Der Mark K. Gauss V. Von Der Mark H. Muller P. Relationship between cell shape and type of collagen synthesised as chondrocytes lose their cartilage phenotype in culture. Nature. 1977;267:531. doi: 10.1038/267531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Darling E.M. Athanasiou K.A. Rapid phenotypic changes in passaged articular chondrocyte subpopulations. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:425. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glowacki J. Trepman E. Folkman J. Cell shape and phenotypic expression in chondrocytes. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1983;172:93. doi: 10.3181/00379727-172-41533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melrose J. Smith S. Ghosh P. Assessment of the cellular heterogeneity of the ovine intervertebral disc: comparison with synovial fibroblasts and articular chondrocytes. Eur Spine J. 2003;12:57. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0434-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mizuno H. Roy A. Zaporojan V. Vacanti C. Ueda M. Bonassar L. Biomechanical and biochemical characterization of composite tissue-engineered intervertebral discs. Biomaterials. 2006;27:362. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gruber H.E. Fisher J. Carl E. Desai B. Stasky A.A. Hoelscher G. Hanley J. Edward N. Human intervertebral disc cells from the annulus: three-dimensional culture in agarose or alginate and responsiveness to TGF-[beta]1. Exp Cell Res. 1997;235:13. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gruber H.E. Leslie K. Ingram J. Norton H.J. Hanley E.N. Cell-based tissue engineering for the intervertebral disc: in vitro studies of human disc cell gene expression and matrix production within selected cell carriers. Spine J. 2004;4:44. doi: 10.1016/s1529-9430(03)00425-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maldonado B.A. Oegema T.R. Initial characterization of the metabolism of intervertebral disc cells encapsulated in microspheres. J Orthop Res. 1992;10:677. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100100510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mizuno H. Roy A. Vacanti C. Kojima K. Ueda M. Bonassar L. Tissue-engineered composites of anulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus for intervertebral disc replacement. Spine. 2004;29:1290. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000128264.46510.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vacanti C. Upton J. Tissue-engineered morphogenesis of cartilage and bone by means of cell transplantation using synthetic biodegradable polymer matrices. Clin Plast Surg. 1994;21:445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong M. Siegrist M. Goodwin K. Cyclic tensile strain and cyclic hydrostatic pressure differentially regulate expression of hypertrophic markers in primary chondrocytes. Bone. 2003;33:685. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00242-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farndale R. Sayers C. Barrett A. A direct spectrophotometric microassay for sulfated glycosaminoglycans in cartilage cultures. Connect Tissue Res. 1982;9:247. doi: 10.3109/03008208209160269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singer V.L. Jones L.J. Yue S.T. Haugland R.P. Characterization of PicoGreen reagent and development of a fluorescence-based solution assay for double-stranded DNA quantitation. Anal Biochem. 1997;249:228. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seidel J. Pei M. Gray M. Langer R. Freed L. Vunjak-Novakovic G. Long-term culture of tissue engineered cartilage in a perfused chamber with mechanical stimulation. Biorheology. 2004;41:445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alini M. Li W. Markovic P. Aebi M. Spiro R.C. Roughley P. The potential and limitations of a cell-seeded collagen/hyaluronan scaffold to engineer an intervertebral disc-like matrix. Spine. 2003;28:446. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000048672.34459.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoon S. Kim K. Li J. Soo Park J. Akamaru T. Elmer W. Hutton W. The effect of bone morphogenetic protein-2 on rat intervertebral disc cells in vitro. Spine. 2003;28:1773. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000083204.44190.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]