Abstract

Dedicated breast computed tomography (CT) imaging possesses the potential for improved lesion detection over conventional mammograms, especially for women with dense breasts. The breast CT images are acquired with a glandular dose comparable to that of standard two-view mammography for a single breast. Due to dose constraints, the reconstructed volume has a non-negligible quantum noise when thin section CT slices are visualized. It is thus desirable to reduce noise in the reconstructed breast volume without loss of spatial resolution. In this study, partial diffusion equation (PDE) based denoising techniques specifically for breast CT were applied at different steps along the reconstruction process and it was found that denoising performed better when applied to the projection data rather than reconstructed data. Simulation results from the contrast detail phantom show that the PDE technique outperforms Wiener denoising as well as adaptive trimmed mean filter. The PDE technique increases its performance advantage relative to Wiener techniques when the photon fluence is reduced. With the PDE technique, the sensitivity for lesion detection using the contrast detail phantom drops by less than 7% when the dose is cut down to 40% of the two-view mammography. For subjective evaluation, the PDE technique was applied to two human subject breast data sets acquired on a prototype breast CT system. The denoised images had appealing visual characteristics with much lower noise levels and improved tissue textures while maintaining sharpness of the original reconstructed volume.

Keywords: breast imaging, breast CT, PDE, volume noise removal

INTRODUCTION

The most common cancer type that affects women globally other than skin cancer is breast cancer.1 Moreover, breast cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related women mortality, secondary only to lung cancer. It is estimated that the disease will kill about 40 480 U.S. women in 2008.1 Although mammography is the standard clinical screening technique2, 3 for breast imaging, superimposition of normal anatomical structures may potentially obscure a breast lesion. The situation gets even worse for women with dense breasts,4 which have more anatomical noise in the projection image. Researchers are developing alternative x-ray breast imaging techniques that may overcome the limitations of mammography, including three-dimensional imaging techniques such as breast tomosynthesis5, 6 and dedicated breast computer tomography (CT).7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Not long after the CT technique was invented in 1972, a group of researchers showed that using a whole body scanner for breast CT imaging would require a high patient dose to achieve adequate image quality.13 With the advent of high-resolution flat-panel detectors at the end of the 1990s, breast CT became an active area of research. In particular, a 2001 article7 showed that dedicated breast CT could achieve quality breast images with dose levels comparable to two-view mammography for the same breast. Other studies have since investigated many aspects of dedicated breast CT.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18

Preliminary human subject data acquired on our first prototype breast CT system19 provide exciting new information of the breast that was not available in the past. However, because the relatively low total dose must be split among a large number of projection views (around 500), reconstructed breast CT thin sections contain considerable quantum noise. Thus, it is desirable to reduce noise levels in the reconstructed volume to improve the conspicuity of breast lesions while also retaining spatial resolution. Alternatively, by applying denoising techniques, dose may be reduced while maintaining the image quality.

For low dose CT, some general-purpose sinogram smoothing techniques based on either penalized likelihood20 or penalized weighted least squares21 were developed. These techniques can be potentially applied on dedicated breast CT data sets. Zhong et al.22 developed a wavelet-based technique and applied it on phantom breast CT data. Their results showed that with denoising, dose could be potentially reduced by up to 60%.

The partial diffusion equation (PDE) based technique23, 24 is another denoising method which is effective not only in removing noise but also in preserving details. Although computationally intensive, this iterative method can provide more freedom in choosing the desired denoising effect. In this study, we describe several variants of the PDE based denoising technique applicable to different steps along the reconstruction process of breast CT and evaluate it both on simulated and empirically collected human subject data sets.

The image quality of PDE denoised images was compared against that of a Wiener filtering technique as well as two-dimensional (2D) adaptive trimmed mean (ATM) filters. Quantitative comparisons were made using simulated data at various exposure levels, while qualitative comparisons were made using dedicated breast CT scan data from two human subjects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Dedicated breast CT system and human subject data sets

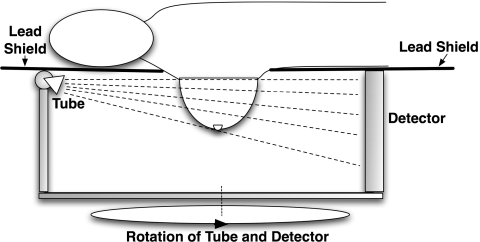

As is illustrated in Fig. 1, dedicated breast CT systems are typically designed as follows: a patient lies prone on a lead-shielded table with one breast hanging through a hole on the table in the pendant geometry. The x-ray tube and the flat-panel detector rotate in the horizontal plane underneath the table. This setup is different from a conventional CT system, where the x-ray tube and detector rotate around the torso of a patient (axial scanning). Since only the breast to be imaged is exposed to the x-ray beam, the dose to the patient can be greatly reduced. A pilot study7 showed that this type of dedicated breast CT system is able to achieve a satisfactory image quality with dose levels comparable to standard two-view mammography for the same breast.

Figure 1.

Illustration of a dedicated breast CT system. The x-ray tube and flat-panel detector rotate together around the breast, which is the only region to be illuminated.

Using the above system design, a custom-designed breast CT system was fabricated at the University of California Davis Medical Center and is currently accruing patient images. The x-ray tube has a Comet beryllium-windowed, water-cooled tungsten anode and a nominal focal spot with the size of 0.4 mm×0.4 mm. A Pantak high frequency x-ray generator drives the tube with the voltage ranging from 10 to 160 kV. The CsI-based flat-panel detector (Varian, PaxScan 4030CB) has a field of view of 40 cm×30 cm. Using 30 frames per second and 2×2 pixel binning mode, the detector generates the images each with matrix size of 1024×768 and pixel dimension of 0.388 mm×0.388 mm. A Kollmorgen servo motor was employed to drive the rotation of the tube-detector gantry as well as encode the angular information. The source-to-isocenter distance is 46.9 cm and the source-to-detector distance is 88.4 cm.

For the two human subject data sets presented in this article, the projection images were acquired under 80 kVp using a circular orbit. The mAs values were chosen for each subject such that the mean glandular dose using breast CT was equal to two-view mammography. Each subject is scanned within 17 seconds to get a total of 500 projection images that span slightly over 360 degrees. After dead pixel and flat field corrections, each data set is ready for tomographic reconstruction.

Simulated breast CT data sets

In this study, simulated breast CT data sets were also generated to aid the analysis. The computer-generated breast is a hemisphere with radius of 7 cm. It has homogeneous breast tissue with a uniform linear attenuation coefficient of 0.17 cm−1 and is surrounded by 1 mm thick skin25 with a linear attenuation coefficient of 0.3 cm−1. Either a contrast detail phantom or a single high-contrast lesion was simulated at the center of the breast. The parameters of the contrast detail phantom are: for each 4 by 4 lesion array, sizes vary vertically (6, 5, 4, and 3 mm); contrasts of the lesions are 15%, 10%, 5%, and 3% from left to right. Five of these arrays were embedded in the shape of a plus sign to cover multiple areas in the central coronal slice in order to detect any regional variations in image quality. Perfect detection would correspond to five sets of 16 lesions or 80 in total. This simulated breast was scanned virtually by a monochromatic x-ray cone beam with infinitely small focal spot and ideal flat-panel detector with 100% detective quantum efficiency. The geometric parameters are the same as the physical breast CT scanner described in the previous subsection.

For each 2D projection image, an analytical line integral image was first obtained based on the aforementioned virtual dedicated breast CT scanning. A noisy raw image was generated according to the measurement model.26 The model takes into account both photon quantum noise and electronic readout noise. It has the following form:

| (1) |

where Gi is the gain factor of the imaging system, is the mean energy level of the polychromatic x-ray beam, and the Gaussian term is for the electronic noise. In our simulation we chose Gi=0.0035∕keV, , and σ2=10. The values of Gi and σ2 were referred to those used in Ref. 26.

Two I0 values are used. The exposure level affects the noise content of line integral at a fixed location. By varying the exposure levels and plotting the line integrals against those of human subject data, it is found that I0=2.5e4 gives a comparable noise level for the same line integral values. Another exposure level is I0=1e4, which is 40% of the first exposure level.

Tomographic reconstruction

Before reconstruction, the raw projection images undergo a preprocessing step. The raw projection image is converted into the line integral via the logarithm operation. On each raw projection image, a region of interest (ROI) is identified which is outside the breast silhouette, and the pixel value without attenuation I0 is approximated by the mean pixel value within the ROI. Then the line integral image is obtained by lij=log(I0∕Iij), where Iij is the pixel value at (i,j) position.

Since the data sets have high angular sampling rate, the computationally efficient filtered backprojection27 (FBP) algorithm was chosen for reconstruction. The Feldkamp type FBP for cone-beam geometry was custom written and a Shepp–Logan filter was used.

Denoising techniques

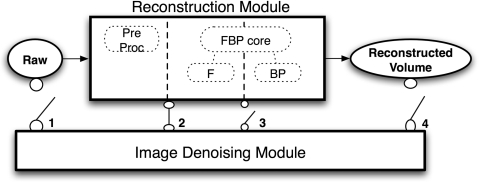

Along the reconstruction process, there are four possible steps where a denoising technique can be applied, as illustrated in Fig. 2. However, applying a denoising technique in step 1 will not be very effective due to the nonlinear operation of the preprocessing step. Only steps 2, 3, and 4 are considered. All together five different denoising techniques were implemented for this study. The first three are variants of the partial diffusion equation based denoising technique that were developed for each step. First, the standard 2D PDE technique was applied at step 3. Second, a spatially variant version of the 2D PDE denoted as PDEtomo is used at step 2. Third, the three-dimensional PDE is used at step 4. The last two techniques are Wiener filter and ATM filter, which are also applied to step 2, and which are compared to the PDEtomo technique.

Figure 2.

Illustration of possible steps where image-denoising module may be applied with respect to reconstruction module for dedicated breast CT data. In this study, the denoising techniques are applied at steps 2–4.

PDE2D

An image is processed by a nonlinear PDE technique through

| (2) |

where ∇I is the gradient of the image I and ∇2I=∇⋅(∇I) is the Laplace operation on I over the spatial variables.28 The function of p(.) is called the diffusivity function, a function of the norm of the gradients in the image |∇I|. It is used to regulate the local smoothness. In the presence of noise, the gradients can be unbounded. To overcome this problem, a Gaussian kernel Gσ with the standard deviation of σ is applied to the image before gradients are computed as Catte et al.29 suggested. A nonlinear PDE can reduce noise while preserving spatial resolution in the image.

In this study, we chose a diffusivity function proposed by Perona and Malik23

| (3) |

where δ0 is a user-specified parameter. When the image gradient norm is very large at a location region, the diffusivity will be very small, and thus the local image values will be preserved within a small time period whereas another more uniform region will be smoothed out at the same time. The parameter δ0 acts like a cutoff value; image regions with gradient norm below δ0 will have more noise removed while regions with a higher gradient norm will stay sharp.

The diffusion equation can be discretized by the finite difference approach using the first-order neighborhood system. Each pixel has four neighbors: the north, south, west, and east neighbor pixels. Assuming Δx=Δy=1 in the two-dimensional case, the discretized version of Eq. 2 is

| (4) |

where ⟨t⟩ and ⟨t+1⟩ represent the iteration step t and t+1, respectively; Δt is the discretized time step; p(.,.)’s are diffusivity function values at the neighboring pixels of location (i,j); and ∇(.,.)I is a notation for the difference between I(.,.) and I(i,j) itself. The parameters of PDE2D are Δt, σ, δ, and the number of iterations (denoted by iter_num).

PDEtomo

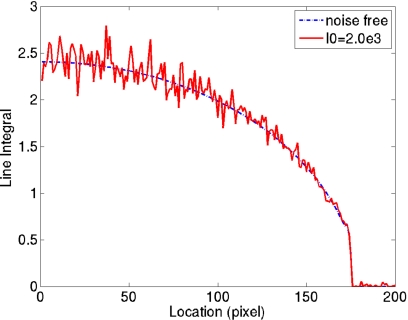

In the breast CT line integral images, noise is larger toward the chest wall. When the photon fluence is reduced, the phenomenon becomes even more obvious. A line profile is shown in Fig. 3 to help illustrate this point. It can be explained theoretically. Again, a simplifying assumption of monochromatic beam is used. If

| (5) |

where λij is the expected number of photons arriving at location (i,j) of the detector, then the variance of the line integral lij can be approximated by the delta method30 using the second-order Taylor expansion

| (6) |

This formalism can be integrated into the PDE denoising technique by adapting the parameter δ in the diffusivity function spatially as

| (7) |

where k is a constant, M is equal to 4, and N(i,j) is the four closest neighbors around pixel (i,j).

Figure 3.

One-dimensional line integral profiles across the breast on a projection image. The dashed and continuous plots correspond to noise free case and the case with I0=2.0e3, respectively. The variance of line integral is larger at the center of breast region and gets lower toward the periphery.

The resultant PDE denoising technique is denoted PDE for tomography∕tomosynthesis (PDEtomo). The parameters to be considered are Δt, σ, δ0, and iter_num.

PDE3Dpost

When the PDE denoising is applied on the reconstructed volume instead of the line integral data, its neighborhood system expands to six neighbors along x, y, and z directions. Otherwise this variant of the algorithm, denoted as PDE3Dpost, is implemented in the same way as PDE2D. For example, the choice of the parameter in diffusivity function is not spatially adaptive, i.e.,

| (8) |

Wiener filter

A Wiener filter is used at step 2 for comparison against the PDE technique investigated in this study. Both techniques are spatially adaptive filters. However, the Wiener filter is a linear technique whereas the PDE technique is nonlinear.

For each pixel, its mean (μ) and variance (σ2) around a local neighborhood is estimated. Then the Wiener filter updates l(x,y) to the new ln(x,y) through

| (9) |

where υ2 is the average of σ2 values.

The variable parameter in the Wiener filter is the size of the neighborhood. In this study, 3×3, 5×5, and 7×7 kernels are considered.

ATM filter

Like the PDE filters described in Secs. 2D1 to 2D3, the ATM filter is also a nonlinear spatially adaptive technique. The one-dimensional (1D) ATM filter presented in Ref. 26 is expanded to 2D. The window size, M, and the trimming parameter, α, are adjusted according to the local pixel value

| (10) |

where x is pixel value on raw projections, and beta and lambda are two parameters of the ATM filter. When x is zero, the window size M obtains its maximal value at beta.

Quantitative image evaluation in simulation studies

For parameter choice and step comparison using the simulated breast with contrast detail phantoms, the figure of merit was the number of detectible lesions, which was counted automatically by thresholding each lesion’s CNR as well as the normalized cross correlation (NCC) of each lesion with its ideal version on the reconstructed coronal slices of the simulated breast.

The CNR is calculated as the ratio of contrast to percentage noise.31 The contrast of the lesion is defined as the signal difference relative to the mean of background, while the percentage noise is the standard deviation of the background relative to its mean. Since both the contrast and noise are relative to the mean of background, the CNR is reduced to the ratio between the signal difference to the standard deviation of the background.

The NCC is a mathematical operation defined as32

| (11) |

where (x,y) and (s,t) are spatial position indices, f and w are an image and a template, respectively, and and are their average values over the space.

The threshold was ad hoc set to 1.0 for CNR and 0.28 for NCC.

To compare quantitatively among various denoising techniques, in addition to the above evaluation on the breast with contrast detail phantoms, we also derived plots of percentage noise against resolution.

In order to measure spatial resolution31 which is a difficult challenge in these nonlinear image processing algorithms, a high intensity sphere was simulated within the breast, projected, and target reconstructed (with an in-plane pixel dimension of 0.2 mm) around the high-intensity sphere. For each specific denoising technique, first the edges of the circular disk within a reconstructed slice were averaged radially. Then, the averaged edge response outside the high-contrast sphere was fitted to a function, which was the convolution of the original edge response without any denoising procedure and a parametric Gaussian function with standard deviation of σ. The best fit Gaussian function was found with the parameter of σbest, and its full width at half maximum, which is equal to 2.35σbest, was used as the measure of the spatial resolution related to a specific denoising technique. Since the spatial resolution was measured from the indirect Gaussian function fitting method instead of directly measuring from the reconstructed slice, it was reasonable to get values less than a pixel size.

RESULTS

Simulation results

Step comparison

With more iteration steps, more noise will also be removed by using PDE based technique, with the tradeoff of degrading resolution. So there is no global optimization of parameters per se. To compare objectively between the PDE variants applied at various steps in the reconstruction process, the parameters are chosen such that same amount of noise will be removed from the reconstructed volumes of breasts. In other words, if a uniform region in the simulated breast without lesions is selected as the background, its noise level is matched among PDE variants. The number of detectible lesions from the contrast detail phantom is used as the figure of merit to select from a subset of parameters that remove the same amount of background noise in the breast. For the comparable noise removal, a matched group is PDEtomo with iter_num=10, Δt=0.1, σ=1 and δ0=0.03, PDE3Dpost with iter_num=4, Δt=0.2, σ=0.15, and δ0=0.07, and PDE2D with iter_num=10, Δt=0.1, σ=5, and δ0=0.09.

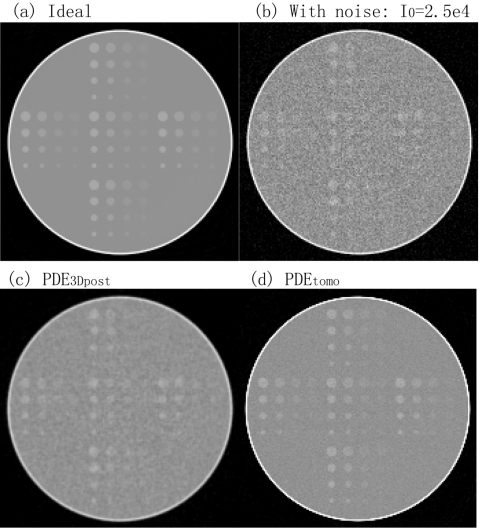

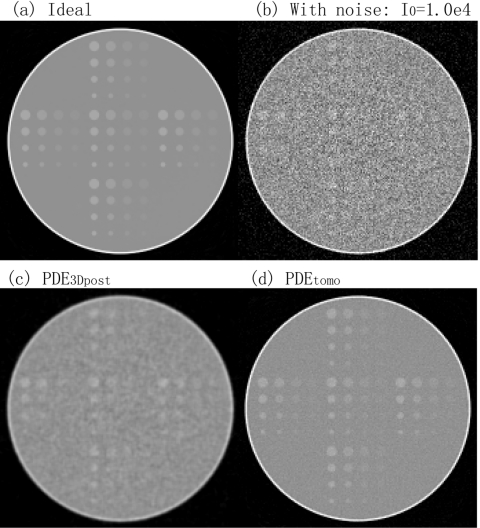

Figure 4 shows the reconstructed thin sections of (a) the ideal contrast detail phantom, (b) the image after adding noise corresponding to exposure I0=2.5e4, (c) the image denoised by the PDE3Dpost algorithm applied at step 4, and (d) the same data denoised by the PDEtomo algorithm applied at step 2. The reconstructed slice thickness was 0.5 mm and within-plane pixel dimension was 0.4 mm. Figure 5 shows the corresponding results at I0=1.0e4. The noise level is higher in Fig. 5b as compared to Fig. 4b. The sensitivity defined as the ratio of the numbers of detectible lesions to the total number of 80 for each case is shown in Table 1. While the CNR and NCC criteria do not give the same number, they provide the same trend: PDEtomo processed volumes (step 2) have more detectible lesions than PDE3Dpost processed ones (step 4).

Figure 4.

Step comparison at I0=2.5e4. (a) is a coronal slice of simulated breast with contrast detail phantoms, and (b) shows the same slice with added noise to the projection images. After noise removal, (d) PDEtomo applied prior to reconstruction generates better images than (c) PDE3Dpost after reconstruction.

Figure 5.

Step comparison at I0=1.0e4. (b) is noisier than Fig. 4b. As in Fig. 4: (d) PDEtomo applied at step 2 is better than (c) PDE3Dpost applied at step 4.

Table 1.

Comparison between denoising applied to reconstruction steps 2 to 4, using CNR and NCC as the criteria. Denoising at step 2 before reconstruction consistently provides a higher number of detectible lesions or a higher ratio of number of detectible lesions to total number of lesions (80 in this study), as does increasing the exposure level.

| Step 2: PDEtomo (%) | Step 3: PDE2D (%) | Step 4: PDE3Dpost (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I0=1e4 | CNR | 55.0 | 53.8 | 45.0 |

| NCC | 53.8 | 53.8 | 42.5 | |

| I0=2.5e4 | CNR | 61.3 | 58.8 | 48.8 |

| NCC | 57.5 | 53.8 | 45.0 | |

In addition, both Figs. 45 show that volumes denoised at step 2 have better visual appearance than those denoised at step 4.

Applying the PDE technique in-between filtering and backprojection steps (step 3) results in reconstructed slices visually similar to Figs. 4d, 5d. However, they have lower sensitivity for detection than PDEtomo at step 2 but higher than PDE3Dpost at step 4, as is shown in Table 1.

Comparison between denoising techniques

Hereafter, denoising techniques are all applied at step 2. Again, the number of detectible lesions from the contrast detail phantom is used as the figure of merit to select the parameters of ATM filter from within all combinations of beta value ranging from 1 to 20 and lambda from 0.5e4 to 7.0e4 with 0.5e4 as the incremental step. The optimized ATM filter has a beta value of 7 and lambda of 2.0e4.

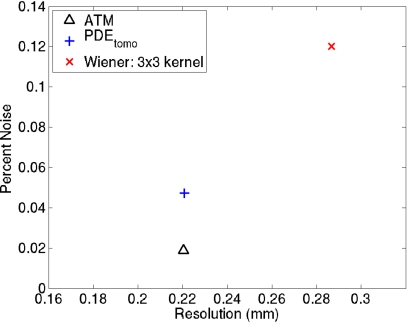

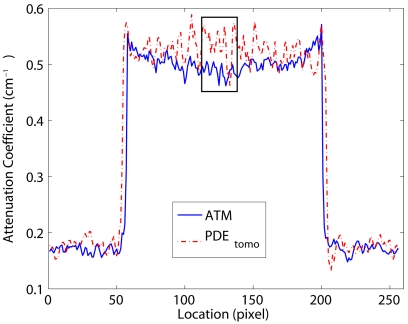

The noise-resolution result at the exposure level of 2.5e4 is given in Fig. 6. It is based on a high-contrast large-size sphere imbedded into the simulated breast. The noise and resolution values are plotted for PDEtomo, Wiener, and ATM techniques. The Wiener filter is applied using a 3×3 kernel. PDEtomo processing resulted in lower noise than Wiener filtering (4.7% and 12%, respectively). At the same time, PDEtomo also provided better resolution than Wiener filtering (0.22 versus 0.29 mm, respectively). The ATM filter provided the same 0.22 mm resolution as PDEtomo, while reducing noise to 2.0%. However, the ATM reconstructed image shows a cupping artifact, which is absent in the PDEtomo processed one. The cupping artifact is evident in the 1D profile through the center of the high-contrast object shown in Fig. 7. Note that the rectangle represents the location where the noise level is measured and does not capture the nonuniformity problem.

Figure 6.

Noise-resolution plot for PDEtomo, ATM, and Wiener filters at I0=2.5e4. For a high contrast test object, PDEtomo and ATM have a lower noise level and higher resolution than Wiener filtering. ATM is the best among the three based on the noise-resolution plot.

Figure 7.

One-dimensional profiles of the reconstruction through the center of the high contrast object using ATM filter and PDEtomo. It is shown that by using ATM filter there is a cupping effect at the lesion center, which is absent from PDEtomo and Wiener processed ones. The rectangle is where the noise level is computed for noise-resolution plot.

To get the number of detectible lesions from the contrast detail phantom or sensitivity comparison, the results from the Wiener 3×3 kernel and 5×5 kernel at exposure level of 1.0e4 were interpolated to match the background noise with PDEtomo. And the background noise level matched ATM filter has parameters of beta of 7 and lambda=1.8e4. The sensitivity results are shown in Table 2. PDEtomo gives the largest number of detectible lesions for the contrast detail phantom, followed by ATM and then the Wiener filter, according to the CNR criterion.

Table 2.

Technique comparison using contrast detail phantoms. PDEtomo is the best among three denoising techniques for this task. All images were acquired with the lower exposure of I0=1.0e4 counts.

| Wiener (%) | ATM (%) | PDEtomo (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNR | 48.8 | 51.3 | 55.0 |

| NCC | 42.5 | 37.5 | 53.8 |

Human subject results

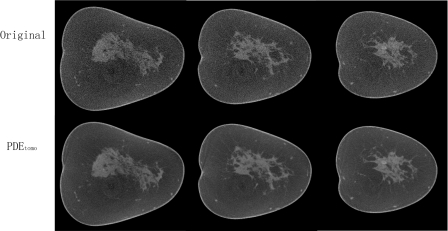

When applied to the clinical data sets, the parameters of PDEtomo used are: Δt=0.1, σ=1, δ0=0.03, and iter_num=10.

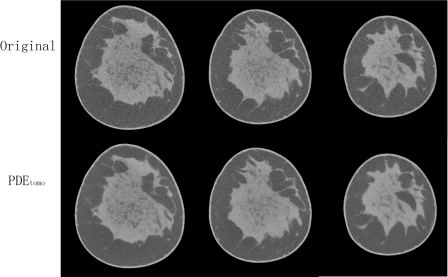

Figures 89 show the coronal reconstructed slices from two human subjects. By visual comparison, the PDEtomo technique (bottom row) reduces the noise considerably while maintaining the resolution of the original reconstruction (top row).

Figure 8.

Human subject result No. 1. Top row shows original reconstruction, coronal slices from normal breast. Bottom row shows same slices with PDEtomo denoising, resulting in remarkably reduced noise levels.

Figure 9.

Human subject result No. 2. Top row shows original reconstruction, coronal slices from normal breast. Bottom row shows same slices with PDEtomo denoising, resulting in markedly reduced noise levels.

DISCUSSION

Dedicated breast CT imaging is an exciting new modality that possesses the potential of improving breast cancer diagnosis over conventional mammography. Some preliminary studies19, 33 show that satisfactory images can be acquired using the same dose as standard two-view mammography. When this dose is divided among the potentially hundreds of individual projection images comprising each scan, the high level of quantum noise in the projection data will pass through to the final reconstructed volume. This motivates the development of denoising tools to effectively remove the noise, improve lesion conspicuity, and maintain image resolution.

One important consideration of noise removal in breast CT is where to apply a denoising technique. In this study, five separate techniques were developed for three different steps in the reconstruction process. By optimizing each of them independently within the subsets that result in the same amount of noise removal from the breast, it was found that denoising before reconstruction provides better images than after reconstruction. This is understandable, since some fine details in the volumes can be overwhelmed by the abundant noise during the reconstruction step. Applying denoising afterwards cannot recover that information. By contrast, if a denoising technique is applied before reconstruction, it is possible for the fine details to be preserved.

Both the quantitative results in the simulation study and the visual inspection in human subject data study showed the promise of the PDEtomo technique. In the simulation study, it was compared with ATM as well as Wiener techniques, two adaptive denoising techniques. The noise versus resolution results show that PDEtomo denoising can achieve lower noise and higher resolution in the reconstructed volume than the Wiener technique. ATM denoising did yield even lower noise, but with cupping artifacts at the center of the breast. In comparison to ATM filtering, PDEtomo provided the same high resolution but the noise levels all over the breast region were more uniform. In addition, the detectability of low contrast lesions was assessed with the use of contrast detail phantoms. PDEtomo once again proved to be the best overall performer, consistently providing the best sensitivity for lesion detection compared to other techniques. The advantage of PDEtomo over other techniques in terms of decreased noise level and improved noise uniformity are both more evident when the dose was lowered to 40% of the original value, which suggests that the PDEtomo technique holds more promise for processing data sets acquired at lower dose levels. With PDEtomo, the sensitivity for lesion detection using the contrast detail phantom drops by less than 7% when the dose is cutoff more than half that of the two-view mammography.

Even though the theoretical description of the noise variance in the projection image due to the quantum noise and the logarithm operation is more approximate for the empirical data, the PDEtomo technique still provides good denoised images.

There are some limitations in this study. First, the simulated breast CT data are based on a monochromatic x-ray beam with the kilovolt (kV) value set to be approximately the same as the effective kV value of the x-ray beam used to acquire the empirical data. Second, the parameters in the measurement model used for adding noise to the simulated projection images are all hypothetical, given that presently their empirical values are unknown. Hence, the task of calibrating the dose in the simulation study cannot be fulfilled at this stage. In future work, considerable optimization remains to be performed to calibrate the PDEtomo technique using empirical images taken with physical phantoms as well as human subjects. Given the robust trends shown in this study, however, the PDEtomo technique should continue to match or outperform the Wiener and possibly ATM technique, especially if dose is further lowered such as to achieve a breast CT scan with equal or less dose than single-view conventional mammograms.

Due to the very low photon fluence on each projection view in dedicated breast CT, the electronic noise is one of the major sources of the overall noise, especially in dense breast regions or if the dose is further reduced. The present version of the PDEtomo technique does not consider the effects of additive electronic noise. It will be worthwhile to explore the possibility of taking the characteristics of this type of noise into account in the denoising technique or to combine it with a statistical-modeling approach that explicitly treats the electronic noise.

In conclusion, a partial diffusion equation based denoising technique was developed specifically for sinogram smoothing in dedicated breast CT data. By incorporating into the algorithm the knowledge of the nonuniform distribution of the noise in the projection image after preprocessing but before reconstruction filtering and backprojection, it provides substantially denoised data with sharp edges. The technique may hold even more promise on data sets acquired with lower dose.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA 94236 and R01 CA 112437) and the U.S. Army Breast Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-05-1-0278). The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

References

- ACS, American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2008 (American Cancer Society, Atlanta, Georgia, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher S. W. and Elmore J. G., “Mammographic screening for breast cancer,” N. Engl. J. Med. 10.1056/NEJMcp021804 348, 1672–1680 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystrom L., Andersson I., Bjurstam N., Frisell J., Nordenskjold B., and Rutqvist L. E., “Long-term effects of mammography screening: Updated overview of the swedish randomised trials,” Lancet 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08020-0 359, 909–919 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson V. P., Hendrick R. E., Feig S. A., and Kopans D. B., “Imaging of the radiographically dense breast,” Radiology 188, 297–301 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niklason L. T. et al. , “Digital tomosynthesis in breast imaging,” Radiology 205, 399–406 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins J. T. and Godfrey D. J., “Digital x-ray tomosynthesis: Current state of the art and clinical potential,” Phys. Med. Biol. 10.1088/0031-9155/48/19/R01 48, R65–R106 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone J. M., Nelson T. R., Lindfors K. K., and Seibert J. A., “Dedicated breast CT: Radiation dose and image quality evaluation,” Radiology 10.1148/radiol.2213010334 221, 657–667 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindfors K. K., Boone J. M., Nelson T. R., Yang K., Kwan A. L. C., and Miller D. F., “Dedicated breast CT: Initial clinical experience,” Radiology 10.1148/radiol.2463070410 246, 725–733 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X., Vedula A. A., and Glick S. J., “Microcalcification detection using cone-beam CT mammography with a flat-panel imager,” Phys. Med. Biol. 10.1088/0031-9155/49/11/005 49, 2183–2195 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C. J. et al. , “Effects of radiation dose level on calcification visibility in cone beam breast CT: A preliminary study,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.656471 6142, 614233 (2006). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. K. and Ning R., “Why should breast tumor detection go three dimensional?,” Phys. Med. Biol. 10.1088/0031-9155/48/14/312 48, 2217–2228 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley R. L., Tornai M. P., Samei E., and Bradshaw M. L., “Simulation study of a quasi-monochromatic beam for x-ray computed mammotomography,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.1668371 31, 800–813 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. H., Sibala J. L., Fritz S. L., Gallagher J. H., Dwyer S. J., and Templeton A. W., “Computed tomographic evaluation of breast,” AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 131, 459–464 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning R., Tang X., and Conover D., “X-ray scatter correction algorithm for cone beam CT imaging,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.1711475 31, 1195–1202 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X., Glick S. J., Liu B., Vedula A. A., and Thacker S., “A computer simulation study comparing lesion detection accuracy with digital mammography, breast tomosynthesis, and cone-beam CT breast imaging,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.2174127 33, 1041–1052 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotty D. J., McKinley R. L., and Tornai M. P., “Experimental spectral measurements of heavy K-edge filtered beams for x-ray computed mammotomography,” Phys. Med. Biol. 10.1088/0031-9155/52/3/005 52, 603–616 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K., Kwan A. L. C., and Boone J. M., “Computer modeling of the spatial resolution properties of a dedicated breast CT system,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.2737263 34, 2059–2069 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu S. J., Shaw C. C., and Chen L. Y., “Noise simulation in cone beam CT imaging with parallel computing,” Phys. Med. Biol. 10.1088/0031-9155/51/5/017 51, 1283–1297 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone J. M. et al. , “Performance assessment of a pendant-geometry CT scanner for breast cancer detection,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.595706 5745, 319–323 (2005). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- La Riviere P. J., “Penalized-likelihood sinogram smoothing for low-dose CT,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.1915015 32, 1676–1683 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Li T. F., Lu H. B., and Liang Z. R., “Penalized weighted least-squares approach to sinogram noise reduction and image reconstruction for low-dose x-ray computed tomography,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 10.1109/TMI.2006.882141 25, 1272–1283 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong J., Ning R., and Conover D., “Image denoising based on multiscale singularity detection for cone beam CT breast imaging,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 10.1109/TMI.2004.826944 23, 696–703 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perona P. and Malik J., “Scale-space and edge detection using anisotropic diffusion,” IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 10.1109/34.56205 12, 629–639 (1990). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weichert J., Anisotropic Diffusion in Image Processing (Tuebner, Stuttgart, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- Pope T. L., Read M. E., Medsker T., Buschi A. J., and Brenbridge A. N., “Breast skin thickness: normal range and causes of thickening shown on film-screen mammography,” J. Can. Assoc. Radiol. 35, 365–368 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh J., “Adaptive streak artifact reduction in computed tomography resulting from excessive x ray photon noise,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.598410 25, 2139–2147 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldkamp L. A. and Kress J. W., “Practical cone-beam algorithm,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1, 612–619 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- McQuarrie D. A., Mathematical Methods for Scientists and Engineers (University Science Books, New York, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- Catte F., Lions P. L., Morel J. M., and Coll T., “Image selective smoothing and edge-detection by nonlinear diffusion,” SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 29, 182–193 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Oehlert G. W., “A note on the delta method,” Am. Stat. 10.2307/2684406 46, 27–29 (1992). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bushberg J. T., Seibert J. A., E. M.Leidholdt, Jr., and Boone J. M., The Essential Physics of Medical Imaging (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, New York, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez R. C. and Woods R. E., Digital Image Processing (Addison-Wesley, New York, 1993). [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. and Ning R., “Cone-beam volume CT breast imaging: Feasibility study,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.1461843 29, 755–770 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]