Abstract

Aim/Hypothesis

Potentially modifiable biomarkers may influence estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decline, but sparse data are currently available in type 2 diabetics.

Methods

We studied 516 type 2 diabetics in the Nurses’ Health Study with data on lipid and inflammatory biomarkers from plasma collected in 1989 and plasma creatinine in 1989 and 2000. Estimated GFR decline ≥ 25% over 11 years was the outcome of interest.

Results

Comparing the highest to the lowest quartile, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor-2 (sTNFR-2) was independently associated with eGFR decline ≥ 25% (multivariate OR 5.81; 95% CI 2.90 to 11.65); this association was stronger in obese women (OR 16.76; 95% CI 4.69 to 59.90 for BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2; OR 2.78, 95% CI 1.12 to 6.89 for BMI < 30 kg/m2; p-for-interaction=0.02). No lipids (total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, non-HDL, triglycerides, lipoprotein-a, or apolipoprotein-B) or other markers of inflammation (C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, E-selectin, ICAM-1, leptin, or adiponectin) were significantly associated with eGFR decline after multivariable adjustment.

Conclusions/Interpretation

Elevated sTNFR-2 levels may be an important and potentially modifiable risk factor for eGFR decline in type 2 diabetes, especially in those with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2.

INTRODUCTION

Identifying biomarkers predictive of estimated glomerular rate (eGFR) decline could point to pathways that may help identify new therapeutics. With the recognition that type 2 diabetes itself may be a chronic inflammatory state, the role of potentially modifiable lipid and inflammatory biomarkers has been of particular interest.

Notably, higher baseline C-reactive protein (CRP) was associated with eGFR decline in people with hyperlipidemia and history of myocardial infarction [1] and in older community-dwelling adults [2]. No relation between CRP and eGFR decline was identified, however, in an analysis of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study [3], but mean duration of follow-up was only 2.2 years. Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor-2 (TNFR-2) has also been associated with eGFR decline [1]. These investigations included <15% diabetics, however.

We previously reported that dylipidemia, higher fibrinogen, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), and sTNFR-2 were independently associated with lower eGFR in a cross-sectional study of men with type 2 diabetes [4]. In this study, we expanded our investigations by examining the relation between lipid and inflammatory biomarkers on 11-year eGFR decline in women with type 2 diabetes.

RESEARCH METHODS

Participants

The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) was initiated in 1976 with the enrollment of 121,700 U.S. nurses aged 30–55 years. Questionnaires are mailed biennially; return of questionnaires constitutes informed consent under the study’s IRB protocol. Between 1989 and 1990, 32,826 participants provided blood samples that were shipped on ice by overnight delivery and stored at 130 degrees Celsius as previously described [5]. In the year 2000, many of these participants submitted a second blood sample under the same shipment and storage conditions.

We mailed a diabetes supplementary questionnaire (DSQ) to all women reporting diabetes on biennial questionnaires. We used the National Diabetes Data Group criteria [6] to define diabetes self-reported up to the 1996 biennial questionnaire. Self-reported diagnosis using the DSQ was 98% accurate in a validation study with medical records review [7].

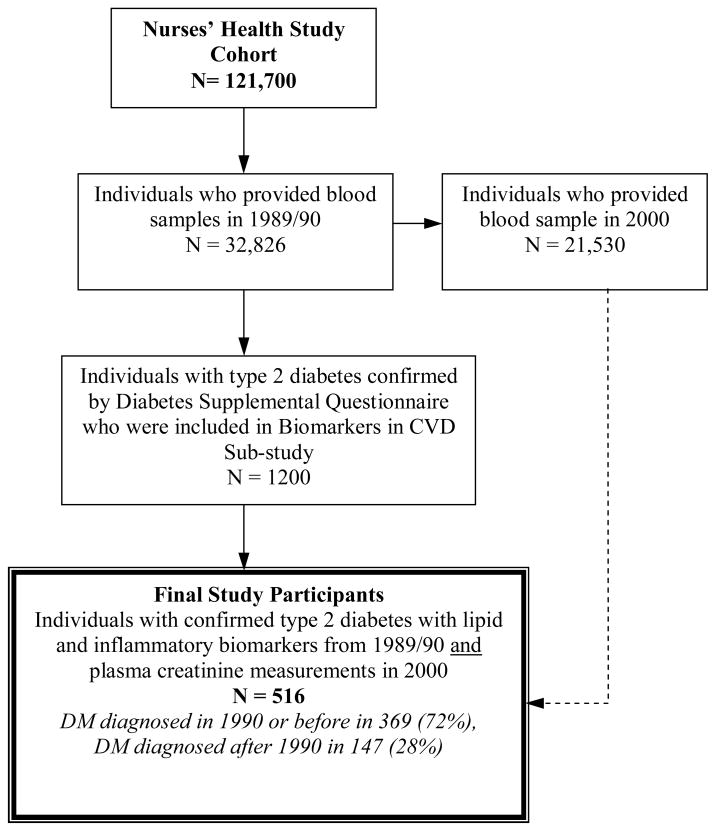

We included women who reported being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes diagnosed up through the year 2000 (because glucose intolerance can precede the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes by ≥ 10 years [8]) and who had plasma samples from both 1989 and 2000. We excluded women with a serum creatinine ≤ 0.5 mg/dl (felt to be implausible) (n=12) and those who were missing data for plasma creatinine (n=19). After applying these criteria, 516 women had eGFR change data available for analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Nurses’ Health Study Biomarkers and Type 2 Diabetes Participant Selection

Biomarker analyses

Biomarker assays were performed at Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA or in the laboratory of Dr. Christos Mantzoros at Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital, Boston, MA using standard methods and assays (Appendix A). On blinded quality control samples that were run simultaneously with participant samples, biomarker measurements had coefficients of variation (CVs) of less than 15% with the exception of E-selectin (CV 20%), adiponectin (CV 27.4%), and sTNFR-2 (CV 16.7%).

Measurements of kidney function decline

Plasma creatinine was analyzed using a modified kinetic Jaffe reaction (CV 10%). In 2007, repeat creatinine assays of 20 NHS plasma samples (with a range of 0.6 to 1.4 mg/dL) initially measured in the year 2000 revealed a mean re-calibration coefficient (new value/original value) of 0.97 and confirmed that creatinine is stable under our storage conditions.

Glomerular filtration was estimated by the 4-variable MDRD equation [9]. An eGFR decline of ≥ 25% between 1989 and 2000 was the primary outcome. An eGFR decline of ≥ 25% over 11 years was determined a priori and has been used in previous analyses of renal function decline in NHS participants [10].

Statistical Analyses

Spearman correlations were performed for eGFR and individual biomarkers at baseline. Multivariable logistic regression modeling was applied to analyze associations between biomarkers and eGFR decline ≥ 25%. Animal protein intake, alcohol intake, and baseline cardiovascular disease were also considered for the adjusted models but were removed as they did not change results. Analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). This study was approved by the Partners’ Healthcare Brigham and Women’s Hospital Human Research Committee Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

In 1989, significant modest cross-sectional inverse correlations were noted between eGFR and leptin (r= 0.16, p<0.001), adiponectin (r= −0.13, p=0.003), and sTNFR-2 (r= −0.28, p<0.001). CRP was not associated with eGFR (r = 0.03, p= 0.57). The women who experienced eGFR decline ≥ 25% between 1989 and 2000 had higher rates of hypertension, CVD, ACE-I/ARB medication use, and lower physical activity. In 1989, only 35 women (6.8%) had eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. In 2000, 139 women (27%) had eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2.

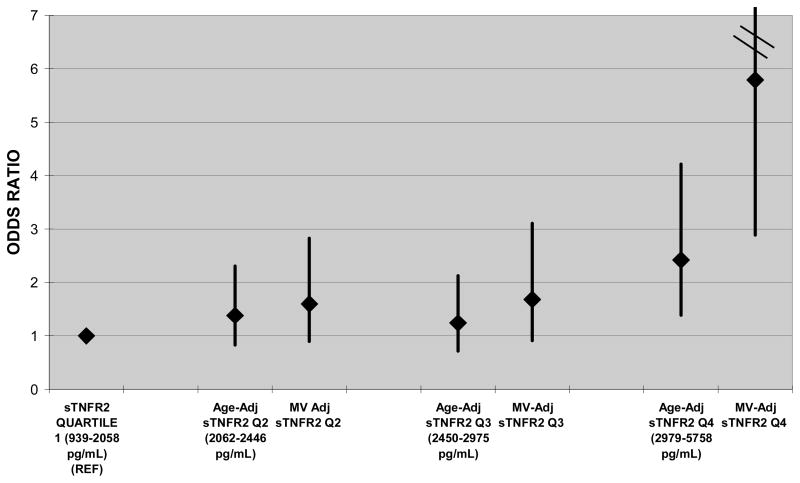

Those in the highest quartile of sTNFR-2 in 1989 had significantly higher odds for eGFR decline ≥ 25% between 1989 and 2000 (multivariate OR 5.81; 95% CI 2.90 to 11.65) (Table 2). Association between sTNFR-2 and eGFR decline was stronger in women with BMI ≥ 30 (OR 16.76; 95% CI 4.69 to 59.9) than in women with BMI < 30 (OR 2.78; 95% CI 1.12 to 6.89) (p-for-interaction=0.02). No other significant associations between biomarkers and eGFR decline were present after multivariable adjustment. Restricting the analyses to the 369 women diagnosed with diabetes in 1990 or before did not meaningfully change the results.

Table 2.

Logistic regression models for odds ratios of ≥ 25% decline in eGFR between 1989 and 2000 for Quartile 4 vs. Quartile 1 of lipid and inflammatory biomarkers

| BIOMARKER | Age-Adjusted Univariate Model (n=516) | Full Model | p-for-trend across quartiles for full model |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR for Q4 vs. Q1 | OR for Q4 vs. Q1 | ||

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 1.48 [0.87, 2.54] | 1.26 [0.70, 2.28] | 0.41 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 1.74 [1.02, 2.96] | 1.36 [0.76, 2.45] | 0.24 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 0.89 [0.52, 1.51] | 0.94 [0.51, 1.74] | 0.66 |

| Non-HDL (mg/dL) | 1.78 [1.03, 3.09] | 1.39 [0.74, 2.58] | 0.32 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 1.32 [0.78, 2.23] | 1.12 [0.62, 2.03] | 0.60 |

| Lipoprotein-a (mg/dL) | 1.19 [0.70, 2.04] | 1.11 [0.61, 1.99] | 0.49 |

| Apoprotein B (mg/dL) | 2.05 [1.20, 3.53] | 1.61 [0.87, 2.99] | 0.24 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 1.43 [0.86, 2.38] | 1.34 [0.72, 2.50] | 0.45 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 1.44 [0.85, 2.45] | 1.67 [0.90, 3.11] | 0.10 |

| E-selectin (ng/mL) | 1.49 [0.89, 2.51] | 0.96 [0.52, 1.80] | 0.84 |

| ICAM-1 (ng/mL) | 1.86 [1.09, 3.18] | 1.55 [0.84, 2.85] | 0.11 |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 1.15 [0.68, 1.94] | 1.81 [0.89, 3.68] | 0.16 |

| Adiponectin (ug/mL) | 0.90 [0.53, 1.52] | 1.22 [0.66, 2.25] | 0.59 |

| sTNFR-2 (pg/mL) | 2.42 [1.39, 4.21] | 5.81 [2.90, 11.65] | <0.001 |

LDL= low density lipoprotein, HDL=high density lipoprotein, CRP= high sensitivity C-reactive protein, ICAM-1=intracellular adhesion molecule, sTNFR-2= soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor-2

Full MV models adjusted for age (continuous, years), hypertension (yes/no), BMI (continuous), ever smoked, physical activity (METS/week), duration of Type 2 diabetes (continuous, years), ACE-I/ARB medication use (yes/no), baseline Hgb A1c%, and eGFR in 1989.

Cumulative averaged animal protein intake, alcohol intake, and baseline cardiovascular diseasewere also considered for inclusion in MV model but did not change estimates between biomarker and eGFR ≥ 25% decline and were therefore removed.

DISCUSSION

After multivariable adjustment, sTNFR-2 was a strong predictor of eGFR decline and varied by obesity status. These data support the theory that sTNFR-2, our surrogate marker for the volatile cytokine TNF-alpha, promotes tubular epithelial apoptosis [11] and progressive renal tubulo interstitial fibrosis [12]. Tubulo interstitial fibrosis is one of the strongest predictors of subsequent kidney disease progression [13], which ultimately manifests as GFR decline. Our findings are consistent with the CARE trial where significantly faster eGFR decline was associated with higher levels of sTNFR-2 [1]. Unlike the CARE study, however, we did not see an association between CRP and eGFR decline. This may be due to the difference in populations (type 2 diabetics vs. mostly non-diabetics with history of MI).

Obesity is an independent predictor of CKD development [14]; we therefore stratified by obesity status, and found that obesity modified the associations between sTNFR-2 and eGFR decline. TNF-alpha is elevated in obese compared to non-obese women and weight loss decreases these cytokine levels [15]. Because adipocytes are now recognized as important regulators of metabolism and inflammation through their secretion of cytokines, chemokines, and hormone-like proteins, we hypothesize that the larger mass of adipose tissue in obese humans may intensify the detrimental effects of elevated sTNFR-2 on kidney function.

We confirmed some of our previous findings from a cross-sectional analysis of 732 men with type 2 diabetes in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study [4]. The strongest correlation with eGFR was seen with sTNFR-2 (r= −0.39, p<0.001 for men, r= −0.28, p<0.001 for women) whereas CRP and eGFR were weakly or not correlated (r = −0.09, p= 0.02 for men and r = 0.03, p= 0.57 for women). No significant relations were noted between dyslipidemia and eGFR in NHS diabetic women whereas in the diabetic men, eGFR was significantly and inversely associated with total cholesterol, triglycerides, non-HDL, Lp (a), and Apo-B. Therefore, it appears that associations between lipids and eGFR may vary by sex.

In contrast to our findings, an analysis of over 4000 participants with type 2 diabetes in the U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study reported that higher baseline triglycerides and LDL cholesterol were independently associated with incident renal impairment (CrCl < 60 ml/min or doubling of plasma creatinine) [16]. The larger number of male and female participants in the UKPDS analysis allowed for examination of incident renal impairment, and the modeling approach used lipids as continuous variables rather than in quantile categories; thus, the results of may not be directly comparable to the current study.

Limitations of this study include the relatively small number of women with eGFR decline ≥ 25% (thus limiting power for this study) and the high CV’s for some of the biomarkers, which resulted in wide confidence intervals; however, the high CV’s would be expected likely to bias the results towards the null whereas an association with eGFR decline was observed. The participants were mostly older Caucasian women so results may not necessarily be generalizable to other populations. Although it is possible that some women with type 2 diabetes who were lost to follow-up would not have been included in these analyses, this would likely bias the results towards the null. Despite these limitations, this study provides new important additional information on biomarkers and kidney function in diabetes, which has not been extensively studied in humans.

We conclude that higher sTNFR-2 is associated with subsequent eGFR decline in women with type 2 diabetes; the relation of sTNFR-2 with eGFR decline appeared stronger in those with BMI ≥ 30. Progressive kidney disease in type 2 diabetes currently represents a major public health problem worldwide and further investigation into its pathogenesis, especially inflammatory pathways, may open new avenues for potential therapeutics. Therefore, future research may include studying whether TNF-α blockade is beneficial in slowing eGFR decline in type 2 diabetes.

Figure 2.

Age-adjusted univariate and multivariable adjusted associations of quartiles of sTNFR-2 with eGFR decline ≥25% between 1989 and 2000. Quartile 1 is referent.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants of the Nurses’ Health Study with type 2 diabetes in year 2000

| eGFR decline ≥ 25% | ||

|---|---|---|

| No (n=346) | Yes (n=170) | |

| Age (years) | 68 | 70 |

| Caucasian | 98% | 97% |

| Hypertension | 73% | 86%* |

| Years since diabetes diagnosis | 13.9 | 16.1 |

| Hgb A1c% (1989) | 6.1 | 6.5* |

| Current smoker | 6.6% | 4.1% |

| Ever smoked | 51% | 54% |

| Alcohol intake (gm/day) | 0.52 | 0.21 |

| Activity level (mets/week) | 8.6 | 4.2* |

| Cardiovascular disease | 19% | 37%* |

| BMI in 1988 (kg/m2) | 29.0 | 29.3 |

| BMI in 2000 (kg/m2) | 29.0 | 30.1 |

| Change in BMI btw 1988 and 2000 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| ACE-inhibitor or ARB medication use | 27% | 36%* |

| Plasma creatinine in 1989 (mg/dl) | 0.77 | 0.71* |

| Plasma creatinine in 2000 (mg/dl) | 0.79 | 1.04* |

| eGFR in 1989 (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 81 | 91* |

| eGFR in 2000 (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 77 | 56* |

Results expressed as % or median

eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate

p<0.05 when compared to referent group (no eGFR decline)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Elaine Coughlan-Gifford for statistical programming support and Manyee To for assistance in manuscript preparation.

FUNDING

This work was supported by NIH grants K08 DK066246 (JL), R03 DK078551 (JL), R01DK066574 (GCC), R01 HL065582 (FBH), R01 DK058845 (FBH), R01 DK058785 (CM), R01 DK079929 (CM), and P01 CA055075.

Abbreviations

- ACE-I

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

- Apo-B

Apolipoprotein B

- ARB

angiotensin-type 2 receptor blocker

- CARE

Cholesterol and Recurrent Events

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CV

coefficients of variation

- DSQ

diabetes supplementary questionnaire

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- HPFS

Health Professionals Follow-Up Study

- HTN

hypertension

- ICAM-1

intracellular cell adhesion molecule1

- Lp(a)

Lipoprotein-(a)

- MI

myocardial infarction

- NHS

The Nurses’ Health Study

- sTNFR-2

Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor-2

- TG

triglycerides

- UKPDS

U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

APPENDIX A (on-line publication only): Detailed Specifics on Biomarkers

The concentrations of total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), and triglycerides (TG) were simultaneously measured on the Hitachi 911 analyzer using reagents and calibrates from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN, USA); coefficients of variation (CV) for these measurements were below 6%. Low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) concentrations (CV 6.9%) were measured by a homogenous direct method from Genzyme Corporation (Cambridge, MA, USA). Non-HDL cholesterol concentrations were calculated by subtracting HDL from total cholesterol. Lipoprotein-(a) (Lp(a)) (CV 5.7%) was measured by a latex-enhanced immunoturbidimetric method (Denka Sieken, Tokyo, Japan). Apolipoprotein B (Apo-B)-100 concentrations (CV 8.2%) were measured via an immunonephelometric assay using reagents and calibrators from Wako Chemicals USA (Richmond, VA, USA).

C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations(CV 8.7%) were measured by use of a high-sensitivity latex-enhanced immunonephelometric assay on a BN II analyzer (Dade Behring, Newark, DE). Fibrinogen (CV 13.7%) was measured with an immunoturbidimetric assay on the Hitachi 911 analyser with reagents and calibrators from Kamiya Biomedical (Seattle, WA, USA) for testing an antigen antibody reaction and agglutination. Concentrations of E-selectin (CV 20%) and soluble intracellular cell adhesion molecule1 (ICAM-1) (CV 13.2%) were measured by commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (R & D Systems). Leptin (CV 21.6%) was measured by an ultra-sensitive ELISA assay, (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Adiponectin (CV 27.4%) was assayed with a radioimmunoassay fromLinco Research, St Charles, MO. Plasma concentrations of soluble fractions of tumor necrosisfactor receptor 2 (sTNFR-2) (CV 16.7%) were measured by use of an ELISA kit using immobilized monoclonal antibody to human sTNFR-2 (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA). Hgb A1c% concentrations were determined based on turbidimetric immuno inhibition using hemolyzed whole blood or packed red cells (CV 4.9%).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

References

- 1.Tonelli M, Sacks F, Pfeffer M, Jhangri GS, Curhan G. Biomarkers of inflammation and progression of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68:237–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried L, Solomon C, Shlipak M, et al. Inflammatory and prothrombotic markers and the progression of renal disease in elderly individuals. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:3184–3191. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000146422.45434.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarnak MJ, Poindexter A, Wang SR, et al. Serum C-reactive protein and leptin as predictors of kidney disease progression in the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study. Kidney Int. 2002;62:2208–2215. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin J, Hu FB, Rimm EB, Rifai N, Curhan GC. The association of serum lipids and inflammatory biomarkers with renal function in men with type II diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int. 2006;69:336–342. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulze MB, Hoffmann K, Manson JE, et al. Dietary pattern, inflammation, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:675–684. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.3.675. quiz 714–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. National Diabetes Data Group. Diabetes. 1979;28:1039–1057. doi: 10.2337/diab.28.12.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shai I, Schulze MB, Manson JE, et al. A prospective study of soluble tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor II (sTNF-RII) and risk of coronary heart disease among women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1376–1382. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.6.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pradhan AD, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Hemoglobin A1c predicts diabetes but not cardiovascular disease in nondiabetic women. Am J Med. 2007;120:720–727. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS. Assessing kidney function--measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473–2483. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin J, Curhan GC. Kidney function decline and physical function in women. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:2827–2833. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang T, Vesey DA, Johnson DW, Wei MQ, Gobe GC. Apoptosis of tubulointerstitial chronic inflammatory cells in progressive renal fibrosis after cancer therapies. Transl Res. 2007;150:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan SB, Cook HT, Bhangal G, Smith J, Tam FW, Pusey CD. Antibody blockade of TNF-alpha reduces inflammation and scarring in experimental crescentic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1812–1820. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nath KA. Tubulointerstitial changes as a major determinant in the progression of renal damage. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;20:1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80312-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster MC, Hwang SJ, Larson MG, et al. Overweight, obesity, and the development of stage 3 CKD: the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:39–48. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ziccardi P, Nappo F, Giugliano G, et al. Reduction of inflammatory cytokine concentrations and improvement of endothelial functions in obese women after weight loss over one year. Circulation. 2002;105:804–809. doi: 10.1161/hc0702.104279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Retnakaran R, Cull CA, Thorne KI, Adler AI, Holman RR. Risk factors for renal dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study 74. Diabetes. 2006;55:1832–1839. doi: 10.2337/db05-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]