Abstract

Aims/Hypothesis

—The majority of type 2 diabetes Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS) to date have been performed in European-derived populations and have identified few variants that mediate their effect through insulin resistance. The aim of this study was to evaluate two quantitative, directly assessed measures of insulin resistance (SI and DI) in Hispanic Americans using an agnostic, high-density SNP scan and validate these findings in additional samples.

Methods

—A two-stage GWAS was performed in IRAS-FS Hispanic-American samples. In Stage 1, 317K single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were assessed 229 DNA samples. SNPs with evidence of association with glucose homeostasis and adiposity traits were then genotyped on the entire set of Hispanic-American samples (n=1190). This report focuses on the glucose homeostasis traits: insulin sensitivity index (SI) and disposition index (DI).

Results

—Although evidence of association did not reach genome-wide significance (P=5×10−7), in the combined analysis SNPs had admixture-adjusted PADD=0.00010–0.0020 with 8–41% differences in genotypic means for SI and DI.

Conclusions/Interpretation

—Several candidate loci have been identified which are nominally associated with SI and/or DI in Hispanic Americans. Replication of these findings in independent cohorts and additional focused analysis of these loci is warranted.

Keywords: Type 2 Diabetes, Insulin Sensitivity, Disposition Index, Hispanic Americans

INTRODUCTION

Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have made major contributions to the understanding of complex genetic traits. Studies in samples of type 2 diabetes cases and controls(e.g. [1–6]) have had an extraordinary impact on the current understanding of genetic susceptibility to type 2 diabetes primarily in European-derived populations. As with many major technical advances, these results have raised additional questions. To date, there have been few type 2 diabetes GWAS in U.S. minority populations[7]. In addition, evaluations of consensus type 2 diabetes associated SNPs from European-derived studies suggest the influence of these polymorphisms in U.S. minorities, especially African Americans, may be limited[7–9]. A feature of these GWAS has been that most of the type 2 diabetes genes identified likely mediate their influence on type 2 diabetes susceptibility through the β-cell. This contrasts with the widely accepted belief that insulin resistance is a major component of type 2 diabetes susceptibility(e.g. [10–14]). One possibility is that GWAS evaluation of type 2 diabetes cases compared with non-diabetic controls may not be an efficient method to locate genes which code for other risk factors for type 2 diabetes, e.g. reduced insulin action, and/or inability of the β-cells to compensate for insulin resistance, i.e. disposition index.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate two quantitative, directly assessed measures of insulin resistance (SI and DI) in a non-European population. Herein, we present results of a two-stage GWAS in Hispanic-Americans from the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Family Study (IRAS-FS). Through an unbiased approach using a high-density SNP scan and follow-up genotyping, we have identified novel loci that contribute could potentially contribute to variation in glucose homeostasis. This report compliments the results published by Rich et al. for the phenotype AIR[15] and Norris et al. for the adiposity phenotypes[16], both in the same cohort. We acknowledge that these results are preliminary and that replication of these findings in independent cohorts is essential.

METHODS

Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Family Study (IRAS-FS) Participants

Study design, recruitment and phenotyping have been described previously[17]. IRAS-FS is a multi-center study designed to identify the genetic determinants of quantitative measures of glucose homeostasis. Members of large families of Hispanic ancestry (n=1334 in 92 pedigrees; San Antonio, TX and San Luis Valley, CO) were recruited and presented in this report. The institutional review boards at each participating analysis and clinical site approved the study protocol and all participants provided written informed consent.

A clinical examination was performed that included a frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test (FSIGT), anthropometric measurements and collection of samples for blood chemistry and biomarker analysis. Measures of glucose homeostasis were derived using mathematical modeling methods (MINMOD)[18] from glucose and insulin values obtained during the FSIGT[19–21]. These estimates included: insulin sensitivity (SI), acute insulin response (AIR) and disposition index (DI; DI=AIR×SI). This is a report of the results for SI and DI.

A subset of IRAS-FS Hispanic Americans (n=229 in 34 families from San Antonio, TX) were chosen for the GWAS. These samples were participants without type 2 diabetes who had complete data for glucose homeostasis and obesity phenotypes, but with age, BMI, and gender composition consistent with the IRAS-FS collection. Samples chosen represented a genetically homogenous population as assessed from Structure analysis[22] using microsatellite markers from the genome-wide linkage scan (e.g.[23,24]). DNA used in the genotyping was obtained from EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines.

Genome-wide association study (GWAS)

Genotyping was performed using 1.5μg of genomic DNA (15μl of 100ng/μl stock) with the Illumina Infinium II HumanHap 300 BeadChips (Illumina, San Diego, CA) at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center using standardized protocol[25]. Genotypes were called based on clustering raw intensity data for the two dyes using the Illumina BeadStudio software. Repeat genotyping of DNA samples was performed once if the overall call rate was < 98%; the sample was rejected if there was no improvement. The average sample call rate was 99.76%. Consistency of genotyping was checked using 18 repeat samples; the concordance rate was 100%. SNPs with Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium P<0.001, minor allele frequency (MAF) less than 0.05 or more than 5% missing genotypes were excluded from subsequent analysis. Genotypes with gencall scores <0.15 were set to missing (0.25%). For highly associated SNPs, clustering was repeated to exclude spurious significance. All genotypes were oriented to the forward strand.

Validation Genotyping in the entire IRAS-FS Hispanic sample

SNPs with evidence of association in the GWAS were validated in the entire Hispanic cohort (excluding subjects with type 2 diabetes). A total of 1536 SNPs were chosen for genotyping on all Hispanic samples (n=1190). Genotyping was performed at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center using the Illumina Golden Gate Assay. SNPs with low call frequencies (<98%) were manually re-clustered (~15% of SNPs). Of the 1536 SNPs, 3.5% were excluded based on call frequency <0.7 and/or cluster separation less <0.3. The average SNP call frequency was 99.48%. Duplicate genotyping of 12 samples was 100% concordant. The minimum acceptable sample call rate was 95%; the average sample call rate was 99.5%. SNP selection for this second stage was based upon 1) identification of the most strongly associated 50–100 SNPs for each trait of interest (see Supplementary Table 1) from the initial GWAS; 2) tag SNPs in genes with high evidence for association across more than one phenotype were selected using the HapMap CEU reference population to capture common variation within the associated LD block; and 3) ancestry-informative markers (AIMs) for Hispanic populations[26,27]. In total, 118 and 96 SNPs for SI and DI, respectively, were selected and successfully genotyped in the validation study.

Follow-up Locus-specific Genotyping

Loci with evidence for association from the GWAS and validation genotyping were targeted for additional genotyping using tag SNPs. Genotyping was performed using iPLEX Gold SBE assays on the Sequenom MassArray Genotyping System (Sequenom, San Diego, CA). Locus-specific primers were designed using the MassARRAY Assay Design 3.0 software and resulting mass spectrograms were analyzed by the MassARRAY TYPER software. The minimum acceptable call frequency was 95%. Fifty one blind duplicates were included to evaluate genotyping accuracy; the concordance rate was 100%. SNPs were chosen to capture common variation within LD blocks as defined by the CEU population of the HapMap project[28]. Specifically, genotype data from the genomic interval containing the candidate gene+/−5kb was exported from the HapMap database and imported into Haploview[29]. For genes with few LD blocks, i.e. VIPR1, SLC1A4 and P2RY2/6, SNPs were selected to tag the entire genic region with a mean r2=0.80 with forced inclusion of previously genotyped SNPs. For larger genes, i.e. MAGI1, KLHL25, MYH13, RGS7 and KIAA1799/PGM1, SNP selection focused on the LD block containing SNPs associated in the validation genotyping and additional SNPs were selected to tag the block with a mean r2=0.80 with forced inclusion of previously genotyped SNPs.

Statistical Methods

For quality control, each SNP was examined for Mendelian inconsistencies using PedCheck[30] and 1657 SNPs exhibiting inconsistencies were converted to “missing.” Maximum likelihood estimates of allele frequencies were computed using the largest set of unrelated Hispanic-American individuals (n=34); SNP genotypes were tested for departures from Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium. SNPs with no evidence of a difference in SI or DI values between individuals with and without missing genotype data (P>0.05), and no evidence of departure from HWE (P>0.001) were included in subsequent analyses.

To test for association between individual SNPs and the traits of interest, i.e. SI and DI, differences in trait values by genotype were tested using the variance components model that explicitly models the correlation among related individuals as implemented in SOLAR[31]. Using this methodology, X-chromosome SNPs were not used in the primary analyses. For statistical testing, SI and DI were transformed using log and signed-square root, respectively, to best approximate the distributional assumptions of the test and minimize heterogeneity of the variance. The primary statistical inference was the additive genetic model which was used to rank SNPs. All tests and levels of significance were computed after adjustment for age, sex and BMI.

Analysis of validation and locus-specific genotyping data followed the same analytical framework as the GWAS, except that covariate adjustment included a term for the site of recruitment (San Antonio, San Luis Valley) and admixture. For admixture analysis, a collection of AIMs was used. These were selected from the literature on studies performed in Hispanics[26,27]. The GWAS had 80 SNPs (including 14 on the X chromosome) and the validation genotyping had 149 SNPs (including 23 on the X chromosome). The 149 AIMs were available on 1279 subjects, and these data were merged with HapMap data for CEPH (n=90) and Yoruba (n=90) populations.

A principal components analysis was performed on the 149 AIMs as well as the 80 AIMs in common between the GWAS (317K SNP panel) and validation (1536 SNP panel) experiments. The total proportion of variance explained by the first three principal components with the 80 AIMs (PC1, 10.2%; PC2, 5.1%; PC3, 2.7%) differed little from the proportion of variance explained by the 149 AIMS (PC1, 10.3%; PC2, 4.8%; PC3, 1.9%). However, there were differences overall between the Hispanic-American sites with respect to PC2 (P=2.35×10−53). In addition, Hispanic Americans from the sites differed in measures of glucose homeostasis (SI, P=0.0006; DI, P=1.8×10−11). For SI and DI, the proportion of variance explained by the center of ascertainment was 0.01% and 1.59%, repectively; thus, all results are presented with adjustment for admixture in addition to age, sex, BMI and recruitment center.

RESULTS

Study Participants

Hispanic-American subjects (n=229) from the San Antonio population with complete phenotypic data and DNA obtained from EBV-transformed cell lines were used in the GWAS (Stage 1). A sample of 814 subjects with DNA and baseline data was used for validation (Stage 2). The total sample of 1,043 Hispanic-American subjects included 59.4% female, average age of 41.1 years, mean SI of 2.16×10−5min−1/[pmol/l], DI of 1324.7×10−5min−1 and BMI of 28.4 kg/m2. Table 1 summarizes relevant demographic measures showing the comparability of Stage 1 and 2 samples. Specifically, there was no significant difference in age (P=0.67), gender (P=0.40), BMI (P=0.084) or DI (P=0.058) and only a modest difference in SI (P=0.045). SI and DI had a modest genetic correlation of 0.38±0.12 in the overall sample.

Table 1.

Demographics for IRAS-FS Hispanic-American samples. Values are reported as the mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise noted. Participants with type 2 diabetes were excluded.

| GWAS Sample (Stage 1) | Validation Sample (Stage 2) | Combined Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | 229 | 814 | 1043 |

| Gender [N (%)] | |||

| Male | 83 (36.2) | 341 (41.9) | 424 (40.6) |

| Female | 146 (63.8) | 473 (58.1) | 619 (59.4) |

| Age (years) | 41.3 ± 13.9 | 41.1 ± 13.9 | 41.1 ± 13.9 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.4 ± 5.9 | 28.1 ± 5.8 | 28.4 ± 5.8 |

| Glucose Homeostasis | |||

| SI (× 10−5 min-1/[pmol/l]) | 1.87 ± 1.91 | 2.25 ± 1.95 | 2.16 ± 1.94 |

| AIR (pmol/l) | 722.9 ± 598.1 | 780.2 ± 678.2 | 766.9 ± 660.5 |

| DI(× 10−5 min-1) | 1035.4 ± 930.2 | 1408.9 ± 1318.9 | 1321.7 ± 1248.7 |

| Fasting Glucose (mmol/l) | 5.22 ± 0.55 | 5.18 ± 0.52 | 5.19 ± 0.53 |

| Fasting Insulin (pmol/l) | 112 ± 77 | 103 ± 78 | 104 ± 78 |

GWAS for SI and DI

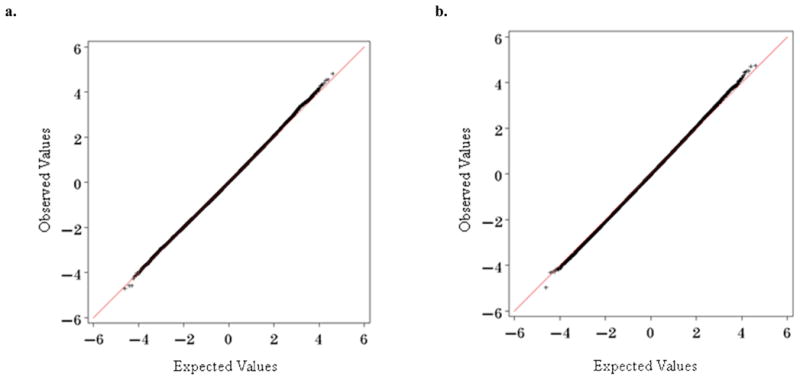

A total of 309,200 SNPs met quality control criteria and were evaluated for association with SI and DI. SNPs were ranked using P-values from the additive genetic model. The Q-Q plot for the stage 1 GWAS indicated that the majority of SNPs exhibited a −log10(P-value)<2 and the observed distribution matched the expectation for the majority of the data (Figure 1). The highest-ranking SNPs associated with SI and DI were chosen for genotyping (Supplementary Table 2) on all Hispanic-American participants in the IRAS-FS (n=1,190). A total of 611 SNPs with evidence of association with SI, DI and other glucose homeostasis phenotypes (SG and AIRg) or SNPs that tag genes associated with multiple phenotypes were included in a 1536 custom chip. For SI and DI, 145 and 98 SNPs, respectively, were chosen for validation (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Quantile-quantile plots for the initial GWAS analysis (n=229). Plots compare observed versus expected values of the Z test statistics under the null hypothesis of no association across the genome. The Q-Q plots are reported with adjustment for age, gender, and BMI. a. Insulin Sensitivity, SI; b. Disposition Index, DI

Candidate genes/Regions of Association for SI and DI

The most significantly associated SNPs for SI and DI are presented in Table 2 ordered by chromosomal position as determined by dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/) using NCBI Build 36.1 (hg18). These hits were A) selected for follow-up from the GWAS based on significance, B) had nominal evidence of association in the Validation sample (P<0.05; Supplementary Table 3) and C) consistency in directionality (beta coefficient) with respect to the same allele (all analyses are presented are with respect to the minor allele). Forty-six of the 145 (31.7%) selected for validation were nominally associated with SI (P<0.05) in the combined analysis (Supplementary Table 4). Two of the strongest associations for SI, rs7091573 and rs6560787, are within 2kb of each other on chromosome 10 (D′=1.00, r2=0.72) near the genomic location of a cDNA for a hypothesized gene AK097474. Additionally, two non-genic SNPs on chromosome 15 (rs7174900 and rs7172316; D′=1.00, r2=1.00) were also significantly associated. Haplotype analysis of high scoring, closely linked SNPs did not provide more strongly associated findings than single SNP analysis (data not shown). Admixture-adjusted PAdditive values for the top hits in the total Hispanic-American population were in the range of 1.0×10−4–1.3×10−3, which are comparable in magnitude to the P-values observed in the GWAS.

Table 2.

Association results for Insulin Sensitivity (SI) and Disposition Index (DI). Additive P-values for SNPs in the GWAS (n=229), Validation (n=814) and Combined (n=1043) samples. SNPs are ranked by signficance with respect to the admixture-adjusted, combined sample additive P-value.

| SNP | Chr | Position | Allelesa | MAFb | Nearest Gene (+/− 10kb) | GWASc | Validationd | Combinedd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI: Insulin Sensitivity | ||||||||

| rs6794189 | 3 | 65618513 | A/C | 0.14 | MAGI1: membrane assoicated guanylate kinase | 0.030 | 0.0039 | 3.92E-04 |

| rs2613675 | 8 | 21095515 | A/G | 0.29 | 7.88E-05 | 0.019 | 3.04E-04 | |

| rs279910 | 9 | 965112 | A/G | 0.35 | DMRT3:doublesex and mab-3 related transcription factor 3 | 6.08E-04 | 0.039 | 0.0013 |

| rs7091573e | 10 | 2053806 | T/C | 0.33 | AK097474: Hypothetical Gene | 6.21E-04 | 0.0052 | 1.03E-04 |

| rs6560787e | 10 | 2051961 | G/A | 0.42 | AK097474: Hypothetical Gene | 4.85E-04 | 0.013 | 2.17E-04 |

| rs7174900f | 15 | 71077956 | T/C | 0.03 | 7.78E-04 | 0.022 | 4.16E-04 | |

| rs7172316f | 15 | 71074205 | T/G | 0.03 | 7.78E-04 | 0.029 | 5.40E-04 | |

| rs7181017 | 15 | 84145916 | C/T | 0.09 | KLHL25: kelch-like 25 (Drosophila) | 4.13E-04 | 0.036 | 0.0011 |

| DI: Disposition Index | ||||||||

| rs217463 | 1 | 63814375 | A/G | 0.35 | EFCAB7: EF-hand calcium binding domain 7 | 3.22E-05 | 0.020 | 6.89E-04 |

| rs3004318 | 1 | 63673327 | T/C | 0.35 | ALG6: asparagine-linked glycosylation 6 homolog | 3.22E-05 | 0.027 | 0.0011 |

| rs7772334 | 6 | 41397828 | G/T | 0.32 | 6.27E-05 | 0.039 | 0.0011 | |

| rs3809738f | 17 | 10217371 | A/G | 0.19 | MYH13: myosin, heavy chain 13, skeletal muscle | 1.87E-04 | 0.048 | 0.0020 |

Major/Minor Alleles; the minor allele is the reference allele for all analyses

Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) determined from the maximum set of unrelated individuals in the combined sample (n=229)

Covariates: Age, Gender, Recruitment Center and BMI

Covariates: Age, Gender, Recruitment Center, BMI and admixture adjustment

D′=1.00; r2=0.72

D′=1.00; r2=1.00

rs3809738 had a HWE P=6.55×10−4 in the Validation sample.

Of the 98 SNPs selected for validation with DI, 31 (31.6%) were nominally associated (P<0.05) in the combined 1536 SNP analysis (Supplementary Table 4). The most associated SNP overall for DI was rs217463 (admixture-adjusted PAdditive=6.89×10−4) in the EFCAB7 gene. Similar to the results with SI, most of the high scoring DI SNPs had broadly comparable P-values in the GWAS. Overall, P-values for SNPs most associated with DI were of a comparable magnitude to the P-values for the SNPs most associated with SI.

Several genes were chosen for additional genotyping and analysis: for SI, RGS7 (regulator of g protein signaling 7); for DI, SLC1A4 and KIAA1799/PGM1 (phosphoglucomutase 1); and for both SI and DI, MAGI1 and VIPR1 (vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 1). Tagging SNPs were chosen to cover these genes, or in the case of very large genes, e.g. MAGI1 (685kb), the LD block containing the associated SNPs. Overall a total of 47 additional SNPs in these six loci were genotyped. Though not striking, this genotyping resulted in additional evidence for association with SI,, trending for RGS7 (PAdditive =0.063 for rs7531569), with DI for SLC1A4 (rs2075209, PAdditive =0.00015) and KIAA1799/PGM1 (rs855315, PAdditive =0.0016; plus two additional SNPs: rs11208250 and rs855325), and both SI and DI for VIPR1 (rs7627240, PAdditive =0.00026; and two additional SNPs for SI: rs421558 and rs417387) and MAGI1 (rs884067, PAdditive =0.00064) (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). These additional SNPs are not highly correlated (r2<0.49) with the initial high scoring SNP or each other.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to survey the genome for evidence of association with two important quantitative measures of glucose homeostasis: insulin sensitivity index (SI) and disposition index (DI). The initial genotyping was performed in 229 subjects from the IRAS-FS San Antonio, TX, population as a rapid and cost effective method for scanning the genome. To our knowledge this is the first report of a GWAS of direct measures of glucose homeostasis, SI and DI. Insulin resistance is an important component of type 2 diabetes risk and an independent risk factor for complications such as atherosclerosis. DI is a strong predictor of conversion to type 2 diabetes[10,32], and thus a phenotype of potentially crucial importance in understanding the genetic underpinnings of type 2 diabetes. While DI has frequently been interpreted as a β-cell functional response to insulin resistance, this phenotype may also capture more central or other tissue effects which regulate glucose homeostasis. The signaling mechanism involved in β-cell compensation is still not clearly delineated[33], leaving the possibility that extrapancreatic factors are changed in those at risk for type 2 diabetes. Such putative signals related to DI-associated loci without a clear link to SI or AIRg, may be of greatest interest for follow-up since they could identify central regulatory pathways of glucose homeostasis.

Genes identified by GWAS from study designs comparing allele frequencies between type 2 diabetes-affected subjects and non-type 2 diabetes controls appear primarily, if not solely, β-cell genes[1–6]. While these observations can be interpreted as a lack of insulin-resistance risk variants, several lines of evidence suggest that GWAS designed around contrasting type 2 diabetes/non-type 2 diabetes subjects may not be optimal for identifying genes influencing insulin sensitivity. Insulin resistance is common in adults. For example, 45–55% of the non-diabetic European-American, Hispanic-American, and African-American participants in IRAS have SI values <1.0 (data not shown). Thus, as many as half of these non-diabetic, middle aged adults are significantly insulin resistant, yet few of the prior type 2 diabetes GWAS have detailed, high quality measures of insulin sensitivity to identify insulin resistance in their control subjects. As an alternative approach, the use of surrogate measures of insulin resistance, e.g. fasting insulin or homeostatic model assessment (HOMAIR), provides some improvement, but in IRAS, Spearman correlations of fasting insulin and SI was −0.61 and HOMAIR and SI was −0.68 among those with normal glucose tolerance[34]. For Hispanic Americans in the IRAS-FS, Spearman correlation of HOMAIR and SI was −0.71, and HOMAIR and DI was −0.46 (data not shown). Importantly, these surrogates correlate especially poorly in subjects with glucose intolerance/insulin resistance with Spearman correlation of HOMAIR and SI of −0.39 and HOMAIR and DI of −0.34 for Hispanic-American subjects with SI<1.0 and fasting insulin and SI of −0.40 and −0.34 in persons with impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes, respectively, in the IRAS-FS (data not shown). In addition, minimal model-based assessment of insulin sensitivity (SI) has been shown to have greater heritability and a different genetic basis than HOMAIR or fasting insulin[35]. It is important to note that minimal model based measurement of SI is a direct measure of insulin sensitivity rather than a surrogate and reflects dynamic measurements of insulin sensitivity compared to HOMAIR which is basal state measurement.

To carry out this study we chose a research design in which a 317K SNP GWAS was performed on 229 Hispanic-American subjects from one clinical center (San Antonio, TX). From the analysis, a set of 1536 high scoring SNPs were chosen for validation in the IRAS-FS Hispanic-American sample in which we have high quality metabolic measures. While we ideally would have carried out a GWAS of the entire sample set, it should be noted that numerous important genes have been identified from GWAS analysis of small initial samples. Examples are the complement factor H gene and macular degeneration ([36]; 224cases/134 controls), NOS1AP gene and cardiac repolarization([37]; 200 subjects), TNFSF15 and Crohn’s disease([38]; 94 subjects) and CDKN2A/B genes with coronary heart disease ([39]; 322 cases/312 controls). While one would expect a high level of noise from the GWAS, it is encouraging to note that 10 of the final top 16 SNPs for SI and 10 of the final top 13 SNPs for DI from the 1536 SNP analysis scored high for these traits in the GWAS stage analysis. Clearly this approach is not perfect though: the highest scoring DI SNP, rs2540970 in SLC1A4, was not associated with DI in the GWAS (P=0.47). This result could have been excluded from further consideration, but it is noteworthy that methodological studies by Skol et al.[40] have suggested that an approach using joint analysis of data is more efficient than replication-based analysis for two-stage GWAS. In follow-up genotyping, two additional SNPs in SLC1A4, rs2075209 and rs6546119, also showed evidence of association with DI (P<0.0043) suggesting SLC1A4 may be associated with DI. With these provisos, we emphasize that the evidence for association does not meet genome-wide significance, and we consider the loci reported here as candidates for future detailed evaluation rather than confirmed SI and DI genes. Relevant to this issue we have generated quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots (Figure 1) from the GWAS analysis. These plots compare the observed versus expected values of the Z test statistics under the null hypothesis of no association across the genome. As expected, the majority of SNPs exhibit a −log10(P-value) <2. The observed distribution of P-values matches expectation for the majority of the observed data, but departs from the null distribution, albeit modestly, for both SI and DI at P<10−3 suggesting at least some of the loci we have detected are genuine SI or DI loci.

Several loci from the GWAS received additional locus-specific follow-up: RGS7 (regulator of g protein signaling 7) with SI, the SLC1A4 gene and KIAA1799/PGM1 (phosphoglucomutase 1) gene cluster for DI, and the MAGI1 gene and the VIPR1 (vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 1) gene for both SI and DI. This analysis did not provide additional compelling evidence that these loci are associated with SI or DI, but nine additional SNPs had nominal evidence of association with P-values ranging from 0.023 to 0.00015 (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). Examination of the top association signals for overlap with previously reported linkage signals[24] did not provide any additional support for the identified loci. Although IRAS-FS has limited power to detect association with type 2 diabetes with 181 type 2 diabetes -affected Hispanic participants, SNPs rs6794189 in MAGI1 and rs10793057 near P2RY2 have evidence of association with type 2 diabetes in discrete trait analysis with P-values of 0.0099 and 0.0016, respectively (data not shown), lending additional support for their relevance.

Gene families are represented in the overall results of the GWAS analysis: MAGI2, in the same family as MAGI1, is nominally associated with DI (data not shown) and several other traits in the study (Haritunians et al., in preparation). SNP rs321983 in MAGI2 is nominally associated with type 2 diabetes (P=0.0072) in the Starr County, TX, Mexican American 100K type 2 diabetes GWAS[7]. The only other SNP which overlapped with previous type 2 diabetes GWAS was rs10504553 in TCEB1, the 11th ranked SNP for SI and 14th for DI in our study, ranked 20th in the Amish type 2 diabetes 100K GWAS[41]. We have reviewed in detail the available results from other type 2 diabetes GWAS (e.g., Diabetes Genetics Initiative, Finland United States Investigation of NIDDM Genetics, and Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium) and subsequent meta-analyses[42] including supplementary material to identify type 2 diabetes associated SNPs that overlap with our study. No overlap was observed with either the individual studies or meta-analysis results.

In spite of the numerous advantages of performing GWAS studies in the IRAS-FS sample, there are limitations. First, there are very few comparable studies with minimal-model assessed SI and DI, especially in Hispanic-American samples. Minimal model assessment of glucose homeostasis measures in diabetics has limitations, so it should be noted that IRAS-FS subjects with a type 2 diabetes diagnosis were excluded from these analyses. The admixture-adjusted, additive P-values that we report do not meet genome-wide significance. SI and DI in our Hispanic families are moderately heritable: SI ranging from 0.29 to 0.38 and DI ranging from 0.20–0.37[35]. The effect sizes reflected in the genotypic means for each SNP as summarized in Supplementary Table 5 are in a range, 8 to 41% of a standard deviation that are consistent with power estimates for this study design. Quantitative measures of glucose homeostasis have greater power on a per individual basis than discrete traits. Under an additive model, MAF=0.15, and α=0.0001 we have estimated power of 0.90 of detecting a 0.30 standard deviation change in the genotypic means. In summary, using a GWAS approach we have identified several genic and non-genic loci that are candidates for association with insulin sensitivity index and disposition index in a sample of Hispanic-American families. More compelling evidence of association with SI and DI will require additional replication samples. In addition, with the study design that we have used (317K SNPs in 229 subjects), the genome has not been covered in detail and other loci influencing SI and DI likely remain to be identified.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NIH grants HL060894, HL060931, HL060944, HL061019, and HL061210; the University of Virginia Harrison Chair in Public Health Sciences (SSR), the Cedars-Sinai Board of Governors’ Chair in Medical Genetics (JIR), the General Clinical Research Centers Program, NCRR grant M01RR00069, and the Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center Grant DDK063491. Mark Brown (WFU) and Adrienne Williams (WFU) assisted in the data analysis.

Abbreviations

- AIM

ancestry-informative marker

- AIRg

acute response to glucose

- BMI

body mass index

- CEPH

Centre d’Etude du Polymorphisme Humain

- DI

disposition index

- FSIGT

frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test

- GWAS

genome-wide association study

- HOMA

homeostasis model assessment

- HWE

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

- IRAS-FS

Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Family Study

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

- MAF

minor allele frequency

- MINMOD

minimal model

- PC

principal components

- Q-Q plot

quantile-quantile plot

- SI

insulin sensitivity

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

Footnotes

Duality of Interest. The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

References

- 1.Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saxena R, Voight BF, Lyssenko V, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies loci for type 2 diabetes and triglyceride levels. Science. 2007;316:1331–1336. doi: 10.1126/science.1142358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott LJ, Mohlke KL, Bonnycastle LL, et al. A genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science. 2007;316:1341–1345. doi: 10.1126/science.1142382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sladek R, Rocheleau G, Rung J, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2007;445:881–885. doi: 10.1038/nature05616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinthorsdottir V, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I, et al. A variant in CDKAL1 influences insulin response and risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:770–775. doi: 10.1038/ng2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeggini E, Weedon MN, Lindgren CM, et al. Replication of genome-wide association signals in UK samples reveals risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Science. 2007;316:1336–1341. doi: 10.1126/science.1142364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayes MG, Pluzhnikov A, Miyake K, et al. Identification of type 2 diabetes genes in Mexican Americans through genome-wide association studies. Diabetes. 2007;56:3033–3044. doi: 10.2337/db07-0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis JP, Palmer ND, Hicks PJ, et al. Association Analysis of European-Derived Type 2 Diabetes SNPs from Whole Genome Association Studies in African Americans. Diabetes. 2008;57:2220–22205. doi: 10.2337/db07-1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer ND, Goodarzi MO, Langefeld CD, et al. Quantitative trait analysis of type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified from whole genome association studies in the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Family Study. Diabetes. 2008;57:1093–1100. doi: 10.2337/db07-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergman RN, Ader M, Huecking K, Van Citters G. Accurate assessment of beta-cell function: the hyperbolic correction. Diabetes. 2002;51 (Suppl 1):S212–220. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.s212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeFronzo RA. Lilly lecture 1987. The triumvirate: beta-cell, muscle, liver. A collusion responsible for NIDDM. Diabetes. 1988;37:667–687. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haffner SM, D’Agostino R, Saad MF, et al. Increased insulin resistance and insulin secretion in nondiabetic African-Americans and Hispanics compared with non-Hispanic whites. The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes. 1996;45:742–748. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.6.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haffner SM, Howard G, Mayer E, et al. Insulin sensitivity and acute insulin response in African-Americans, non-Hispanic whites, and Hispanics with NIDDM: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes. 1997;46:63–69. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muoio DM, Newgard CB. Mechanisms of disease: molecular and metabolic mechanisms of insulin resistance and beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:193–205. doi: 10.1038/nrm2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rich SS, Goodarzi MO, Palmer ND, et al. A genome-wide association scan for acute insulin response to glucose in Hispanic-Americans: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Family Study (IRAS FS) Diabetologia. 2009;52:1326–1333. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1373-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norris JM, Langefeld CD, Talbert ME, et al. Obesity. Silver Spring; 2009. Genome-wide Association Study and Follow-up Analysis of Adiposity Traits in Hispanic Americans: The IRAS Family Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henkin L, Bergman RN, Bowden DW, et al. Genetic epidemiology of insulin resistance and visceral adiposity. The IRAS Family Study design and methods. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:211–217. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(02)00412-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pacini G, Bergman RN. MINMOD: a computer program to calculate insulin sensitivity and pancreatic responsivity from the frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1986;23:113–122. doi: 10.1016/0169-2607(86)90106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergman RN, Finegood DT, Ader M. Assessment of insulin sensitivity in vivo. Endocr Rev. 1985;6:45–86. doi: 10.1210/edrv-6-1-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergman RN, Ider YZ, Bowden CR, Cobelli C. Quantitative estimation of insulin sensitivity. Am J Physiol. 1979;236:E667–677. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1979.236.6.E667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steil GM, Volund A, Kahn SE, Bergman RN. Reduced sample number for calculation of insulin sensitivity and glucose effectiveness from the minimal model. Suitability for use in population studies. Diabetes. 1993;42:250–256. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rich SS, Bowden DW, Haffner SM, et al. A genome scan for fasting insulin and fasting glucose identifies a quantitative trait locus on chromosome 17p: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study (IRAS) family study. Diabetes. 2005;54:290–295. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rich SS, Bowden DW, Haffner SM, et al. Identification of quantitative trait loci for glucose homeostasis: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS) Family Study. Diabetes. 2004;53:1866–1875. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gunderson KL, Steemers FJ, Ren H, et al. Whole-genome genotyping. Methods Enzymol. 2006;410:359–376. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)10017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choudhry S, Coyle NE, Tang H, et al. Population stratification confounds genetic association studies among Latinos. Hum Genet. 2006;118:652–664. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-0071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seldin MF, Tian C, Shigeta R, et al. Argentine population genetic structure: large variance in Amerindian contribution. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2007;132:455–462. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Connell JR, Weeks DE. PedCheck: a program for identification of genotype incompatibilities in linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:259–266. doi: 10.1086/301904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Almasy L, Blangero J. Multipoint quantitative-trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1198–1211. doi: 10.1086/301844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergman RN, Finegood DT, Kahn SE. The evolution of beta-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. Eur J Clin Invest. 2002;32 (Suppl 3):35–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.32.s3.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SP, Catalano KJ, Hsu IR, Chiu JD, Richey JM, Bergman RN. Nocturnal free fatty acids are uniquely elevated in the longitudinal development of diet-induced insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1590–1598. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00669.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saad MF, Anderson RL, Laws A, et al. A comparison between the minimal model and the glucose clamp in the assessment of insulin sensitivity across the spectrum of glucose tolerance. Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes. 1994;43:1114–1121. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.9.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bergman RN, Zaccaro DJ, Watanabe RM, et al. Minimal model-based insulin sensitivity has greater heritability and a different genetic basis than homeostasis model assessment or fasting insulin. Diabetes. 2003;52:2168–2174. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.8.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards AO, Ritter R, 3rd, Abel KJ, Manning A, Panhuysen C, Farrer LA. Complement factor H polymorphism and age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:421–424. doi: 10.1126/science.1110189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arking DE, Pfeufer A, Post W, et al. A common genetic variant in the NOS1 regulator NOS1AP modulates cardiac repolarization. Nat Genet. 2006;38:644–651. doi: 10.1038/ng1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamazaki K, McGovern D, Ragoussis J, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in TNFSF15 confer susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3499–3506. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McPherson R, Pertsemlidis A, Kavaslar N, et al. A common allele on chromosome 9 associated with coronary heart disease. Science. 2007;316:1488–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1142447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skol AD, Scott LJ, Abecasis GR, Boehnke M. Joint analysis is more efficient than replication-based analysis for two-stage genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:209–213. doi: 10.1038/ng1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rampersaud E, Damcott CM, Fu M, et al. Identification of novel candidate genes for type 2 diabetes from a genome-wide association scan in the Old Order Amish: evidence for replication from diabetes-related quantitative traits and from independent populations. Diabetes. 2007;56:3053–3062. doi: 10.2337/db07-0457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeggini E, Scott LJ, Saxena R, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:638–645. doi: 10.1038/ng.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.