Abstract

A new method for measuring the fixed charge density (FCD) in intervertebral disc (IVD) tissues employing a two-point electrical conductivity approach was developed. In this technique, the tissue is first confined and equilibrated in a potassium chloride (KCl) solution, and the tissue conductivity is then measured. This is then repeated with a second concentration of KCl solution. The FCD can be determined from the conductivity measurements. Using this method, the FCD values of bovine annulus fibrosus (AF) and nucleus pulposus (NP) tissues were determined to be 0.060 ± 0.027 mEq / g wet tissue and 0.19 ± 0.039 mEq / g wet tissue, respectively. The FCD of AF was significantly lower than that of NP tissue, similar to results in the literature for human IVD tissues. In order to verify the accuracy of the new method, the glycosaminoglycan (GAG) contents of the tissues were measured and used to estimate the tissue FCD. A strong correlation (R2 = 0.84 – 0.87) was found to exist between FCD values measured and those estimated from GAG contents, indicating that the conductivity approach is a reliable technique for measuring the FCD of IVD tissues.

Keywords: annulus fibrosus, nucleus pulposus, proteoglycan, glycosaminoglycan, electrical conductivity

INTRODUCTION

Low back pain is a prevalent ailment in the United States, afflicting approximately 15–45% of the population annually, and more than 70% of all individuals at some point in their lifetime.51 The annual expense of low back pain is upwards of $100 billion, including both direct and indirect costs, making it a significant economic concern. Despite this, the exact cause of low back pain remains unknown. However, many believe that degeneration of the intervertebral discs (IVD) of the spine is a primary etiologic factor contributing to the onset of low back pain.4;9;33;63

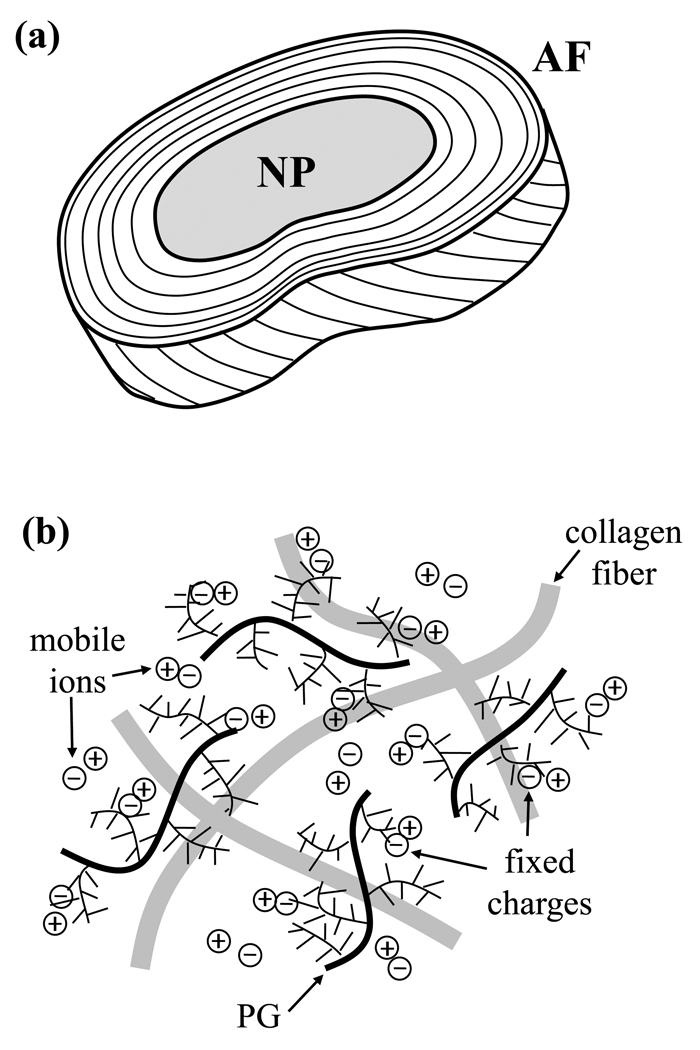

The IVD consists of the nucleus pulposus (NP), the annulus fibrosus (AF) and cartilaginous endplate, each of which has a unique composition and structure.21;41 In this study, the nucleus pulposus and annulus fibrosus are investigated, see Figure 1a. The central NP is made of randomly oriented collagen fibers enmeshed in a proteoglycan (PG) gel. The AF surrounds the NP and is made up of a series of concentric lamellae having a highly organized structure of collagen fiber bundles.25;42 The disc consists primarily of water, comprising 60–90% of the wet weight, and also has significant quantities of collagen (10–50% dry weight) and PG (15–45% dry weight).9;15;17;24;31;35;53;54 The composition of the AF varies from that of the NP, with the AF having a higher collagen content, and lower water and PG contents compared with NP tissue.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic showing the structure of the intervertebral disc; samples were taken from both the annulus fibrosus (AF) and nucleus pulposus (NP) regions of the disc. (b) Schematic diagram showing the charged extracellular matrix of IVD tissue; PG indicates proteoglycan.

The IVD is characterized as a charged, hydrated soft tissue. The negatively-charged nature of the disc results from the charged groups on glycosaminoglycan (GAG) molecules on the PGs found in the extracellular matrix of the disc, see Figure 1b. The fixed charge density (FCD) is a measure of the negative charges (per unit volume) attached to the disc matrix. The electrostatic interactions between fixed charges and mobile free ions result in physiochemical and electrokinetic effects, including Donnan osmotic pressure and swelling, streaming current and potential, and electro-osmosis effects.8;14;17;18;36;58;59 Therefore, both the transport of solutes and fluid and the swelling behavior in the disc are dependent upon many physiochemical factors, including FCD.13;15;18;19;58 Consequently, it is necessary to determine the FCD of IVD tissue in order to quantify the transport behavior in the disc, as well as provide insight into the mechanical behavior of the tissue.

In previous studies, both destructive and non-destructive techniques for measuring FCD in cartilaginous and IVD tissues have been developed, including tracer cation methods, electrokinetic or streaming potential techniques, imaging methods (e.g., MRI, NMR spectroscopy, and micro-CT), and indentation testing.1;3;6;7;10;11;14;27;37–40;43;44;46;48–50;52;56;60–62 The tracer cation technique, developed by Maroudas and Thomas48 has generally been considered the “gold standard” for measuring the FCD of cartilaginous tissues. However, due to the potential hazard of using radio-labeled ions, this method has not been commonly used in regular laboratories. Therefore, there is a need for a new method for measuring tissue fixed charge density that is safe, reliable and easy to perform at a low cost. Hasegawa et al. previously correlated conductivity with FCD for articular cartilage.22 However, to our knowledge, no previous study has used electrical conductivity to measure tissue FCD. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to develop a new technique for measuring the fixed charge density of intervertebral disc tissue. This new approach employed a two-point conductivity method. The technique was verified by measuring the glycosaminoglycan contents of the tissue specimens, and correlating results with the values of FCD calculated. This study is important in further understanding the transport and mechanical behavior of IVD tissues, as both are dependent upon the tissue fixed charge density.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

The electrical conductivity (χ) of a tissue under zero fluid flow conditions is given by23:

| (1) |

where Fc is the Faraday constant, R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, ϕW is the water volume fraction, z is the valence of a particular ion, c is the concentration of the ion, and D is the diffusion coefficient of the ion. For potassium chloride (KCl), where the value of z for K+ is +1 and that for Cl− is −1, the equation reduces to:

| (2) |

For negatively charged tissues, such as IVD and articular cartilage, the ion concentrations are related through the electroneutrality condition32;36:

| (3) |

where cF is the absolute value of the negative fixed charge density. The ion concentrations within the tissue can be calculated from the ideal Donnan equation43;45:

| (4) |

| (5) |

where c* is the concentration of the bathing solution.

In this study, a new method was proposed for determining the fixed charge density (FCD) in intervertebral disc tissue using an electrical conductivity approach. This measurement can be achieved by equilibrating the tissue specimens in two concentrations of solution and measuring the corresponding value of electrical conductivity of the tissue. For KCl solution, because the Stokes’ radii (rs) of K+ and Cl− are approximately equal (for K+, rs = 0.137 nm and for Cl−, rs = 0.142 nm20;34), the values of their diffusion coefficients can also be approximated as equal.20 Therefore, Eq. (2) can be reduced to:

| (6) |

Because the values for electrical conductivity, χ, water content, ϕW, and temperature, T, can be measured, and those for concentration of bathing solution, c*, Faraday’s constant, Fc, and the gas constant, R, are known, only two unknowns remain in Eq. (6): FCD (cF) and ion diffusivity (D). Assuming that ion diffusivity is independent of bathing solution concentration, the values for FCD and diffusivity can be evaluated using simultaneous equations. That is, by measuring the conductivity of a tissue equilibrated in two different known concentrations of KCl bathing solution (i.e., a two-point method), the FCD and ion diffusivity in a given tissue can be determined. Because the value of FCD for a tissue specimen remains constant, given that no swelling occurs (i.e., water content remains constant), we can show that:

| (7) |

where c1* and c2* are the two bathing solution concentrations. Therefore, tissue fixed charge density can be calculated by:

| (8) |

where are the values for electrical conductivity for a tissue specimen equilibrated in bathing solutions with concentrations , respectively, at the same temperature. Here, the tissue fixed charge density is determined in units of moles of charge per fluid volume (m3) in the tissue. Thus, by measuring the electrical conductivity of a tissue specimen equilibrated in two different concentrations of KCl solution, the FCD of the tissue can be determined.

Additionally, as was previously noted, this method also yields the value for K+ or Cl− ion diffusivity in tissue. The value of ion diffusivity can be determined from the equation:

| (9) |

This again assumes that the conductivity measurements are taken at the same temperature, and that the value of ion diffusivity is independent of the concentration of bathing solution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimen Preparation

Three lumbar discs (L3–4, L5–6, L6–7) were harvested from two bovine lumbar spines (~3–6 months) obtained from Animal Technologies, Inc. (Tyler, TX). Cylindrical specimens having a 5 mm diameter and a 3 mm thickness were prepared from both AF and NP tissues using a stainless steel corneal trephine (Biomedical Research Instruments, Inc., Silver Spring, MD) and sledge microtome (Model SM2400, Leica Instruments, Nussloch, Germany) with freezing stage (Model BFS-30, Physitemp Instruments Inc., Clifton, NJ). All specimens were prepared with axial orientation. Two groups of specimens were tested in this study: AF (n=15) and NP (n=15).

Specimen Equilibration

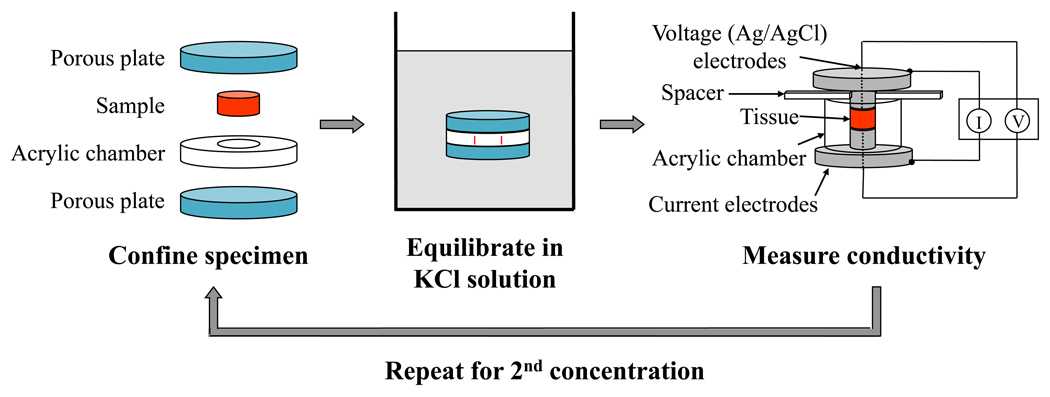

Following preparation, specimens were confined both radially, in an acrylic chamber, and axially, via two sintered stainless steel filters (316L stainless steel, 40µm pore size, 50% open area, Small Parts, Inc., Miami Lakes, FL), see Figure 2. To minimize swelling and PG leaching, the tissue specimens were confined while equilibrating in the bathing solution. The confined specimens were then placed in a beaker filled with KCl solution with the desired concentration, either 0.2 M or 0.02 M. These concentrations were chosen based on the results of a preliminary study using agarose gels, which showed that these were the optimal conditions for this experimental method (data not shown). The beaker was sealed with parafilm. Each equilibration period lasted a minimum of 24 hours at 4°C.

Figure 2.

Flowchart detailing the experimental protocol of the two-point conductivity method for measuring FCD. The sample was first confined in an acrylic chamber between two porous plates and was then immersed in KCl solution for equilibration. Following equilibration, the sample was moved to the conductivity apparatus, where the resistance across the specimen was measured using a 4-wire sense-current method. The procedure was repeated with a second concentration of KCl solution.

Conductivity Measurements

A previously-developed conductivity apparatus12;13;28 was used to measure the electrical conductivity of IVD samples at zero fluid flow conditions, see Figure 2. The apparatus consisted of two stainless steel current electrodes coaxial to two Teflon-coated Ag/AgCl voltage electrodes, a spacer, and a non-conductivity acrylic chamber. Using a Keithley SourceMeter (Model 2400, Keithley Instruments Inc., Cleveland, OH), a four-wire sense current method was applied, and the resistance (Ω) across the specimen was measured at a very low, constant current of 10 μA. The electrical conductivity, χ, of the specimen was calculated from:

| (10) |

where h is the thickness of the specimen and A is the cross-sectional area.

Conductivity values were determined for specimens equilibrated in two different concentrations of KCl solution. Following equilibration, each specimen was transferred from the confining apparatus to the conductivity chamber for resistance measurement. Then, the specimen was again confined for equilibration in a new solution. Following the two resistance measurements, the water volume fraction of each sample was measured.

Water Content Measurement

The water content, or porosity, of each sample was measured using a buoyancy method published in the literature.15;16 Briefly, the tissue specimen was weighed in air (Wair) and in PBS solution (WPBS), and then lyophilized to obtain the specimen dry weight (Wdry). The water content was then calculated by:

| (11) |

where ρPBS and ρw are the mass densities of PBS and water, respectively.

Measurement of GAG Content

Samples were analyzed for glycosaminoglycan content using a 1,9-dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) binding assay.10 Prior to lyophilizing the AF samples, the tissue was chopped into small pieces to facilitate tissue digestion; preliminary studies showed that this was not necessary for the NP samples. The dry tissue specimens were solubilized using 0.5 mg/mL proteinase-K (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 65°C for 18 – 24 hours. The DMMB assay was applied to the digested sample and the absorbance of light at 525 nm was measured spectrophotometically (SmartSpec Plus Spectrophotometer, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA). The tissue GAG content was determined using a bovine chondroitin sulfate type A standard. Values were normalized by tissue dry weights.

RESULTS

The results for fixed charge density, glycosaminoglycan content, and water content in bovine lumbar AF and NP tissues are shown in Table 1. All values were determined at room temperature (23.8 ± 0.24 °C) and are shown in mean ± standard deviation. The units for tissue fixed charge density were converted from equivalent moles per m3 to milli-equivalent moles (mEq) per gram wet tissue using water content measurements; this conversion allowed for comparison of results with those in the literature.60;61 A Student’s t-test was performed using Excel Spreadsheet software (Microsoft Corp., Seattle, WA) to determine if the differences between AF and NP groups were statistically significant for each of the measured parameters. The significance level was set at P<0.05. Analysis showed that significant differences existed between AF and NP tissues for fixed charge density, GAG content, and water content.

Table 1.

Results for volume fraction of water (ϕw), fixed charge density (FCD) and glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content for bovine lumbar AF and NP tissues. Values were determined at room temperature (23.8 ± 0.24 °C). For each group, n=15. For all measures, AF < NP (P<0.05).

| AF | NP | |

|---|---|---|

| ϕw | 0.81 ± 0.054 | 0.93 ± 0.022 |

| FCD (mEq / g wet tissue) | 0.060 ± 0.027 | 0.19 ± 0.039 |

| GAG per dry weight (µg / mg) | 54 ± 41 | 490 ± 64 |

DISCUSSION

In this study, a new technique for measuring the fixed charge density of intervertebral disc tissue was developed, employing a two-point conductivity approach. Using this technique, the FCD of both AF and NP tissues from bovine lumbar discs was measured; the results of this study, ranging from 0.026 to 0.261 mEq/g wet tissue, were similar to those found in the literature for human IVD specimens (~ 0.08 to 0.28 mEq/g wet tissue).60;61 It was also determined that the FCD in AF tissue is significantly lower than that in NP tissue for bovine lumbar IVD, which is in agreement with results for human IVD in the literature.60;61

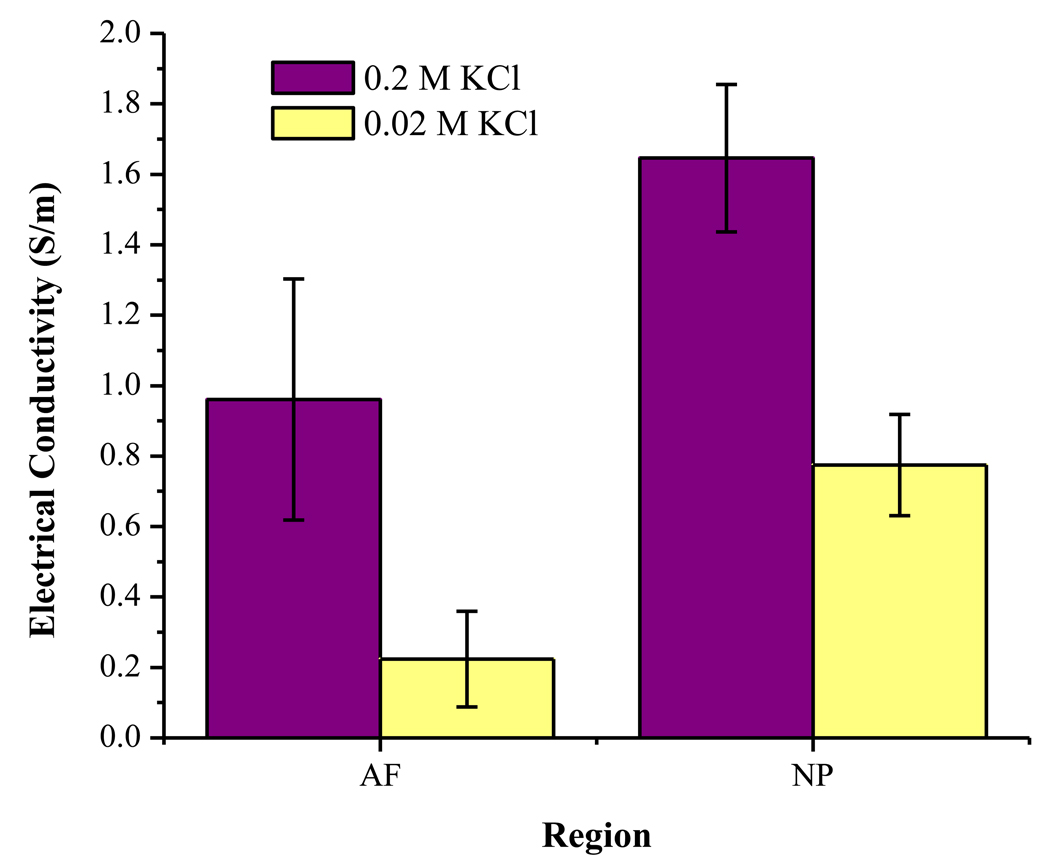

To calculate the FCD with this new method, the electrical conductivity of the tissue specimens in two different concentrations of KCl bathing solutions (i.e., two-point method) was measured. The results for measured conductivity in AF and NP tissues at two concentrations are shown in Figure 3. For both concentrations, the conductivity of AF tissue was significantly lower than that of NP tissue (t-test, P<0.05), which is in agreement with previous studies in the literature using bovine and human IVD tissues.28;29 Furthermore, for both AF and NP tissues, the conductivity values for tissue equilibrated in 0.02 M KCl solution were significantly lower than those equilibrated in 0.2 M KCl (t-test, P<0.05). This is in agreement with a previous study showing that the conductivity of articular cartilage decreased significantly with decreasing bathing solution concentration.44

Figure 3.

Results for electrical conductivity in AF and NP tissues equilibrated in 0.2 M KCl and 0.02 M KCl. For each group, n=15. For conductivity in both solutions, AF < NP (t-test, P<0.05). For conductivity in both tissues, 0.02 M KCl < 0.2 M KCl (t-test, P<0.05).

In order to determine if the new method was able to reliably measure the FCD of IVD tissue, the GAG content of tissues was also measured for comparison. The values for the GAG content of bovine lumbar IVD tissues measured in this study, shown in Table 1, were similar to values found in the literature.2;26;55 The GAG content of AF tissues measured here is slightly lower than those found in the literature for calf lumbar spine.2 However, it should be noted that previous studies indicated that the GAG content increases moving from outer to inner AF.26 While the region of specimens was not specifically noted in this study, most samples were taken from the outer area of the AF; this may account for the lower value for GAG content for AF tissue found here.

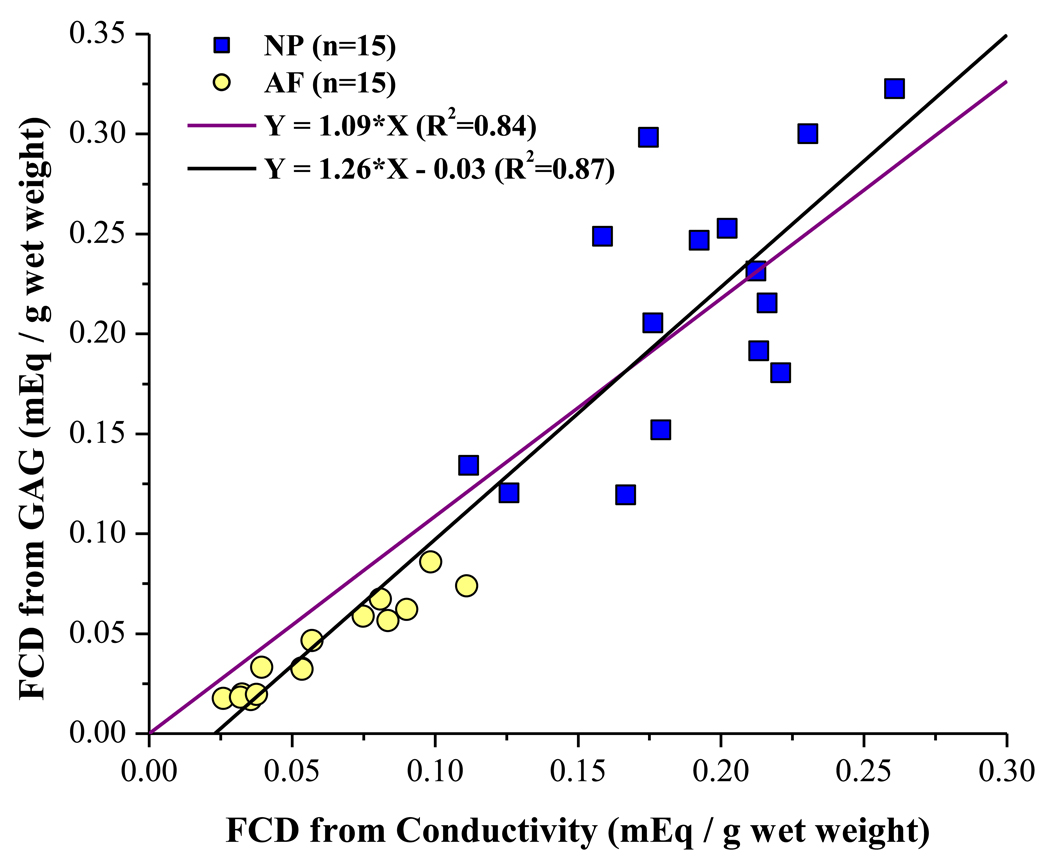

The FCD of a tissue may be estimated from the GAG content within the tissue using the relationship between the molecular weight of a chondroitin sulfate disaccharide and the quantity of charge on each disaccharide unit. By assuming 2 moles of charge per mole of GAG in the tissue and a molecular weight of 502.5 g/mole GAG, the FCD (in mEq / g wet tissue) can be calculated using the following equation1;38:

| (12) |

where WGAG is the GAG content (in grams) in the sample, and Wair is the weight of the wet tissue in air [from Eq. (11)]. The results for GAG contents in AF and NP tissues were used to estimate the FCD for comparison with the results from conductivity testing. For AF tissue, the average FCD calculated from Eq. (12) was 0.043 ± 0.023 mEq / g wet tissue, while that in NP was 0.215 ±0.065 mEq / g wet tissue. A graph showing the measured FCD versus the estimated FCD is shown in Figure 4. Two linear curve-fits were performed, one with the constraint of passing through the origin, and another without this constraint. Both show significant correlations (R2 = 0.84 and R2 = 0.87, respectively) between the measured and estimated values for the tissue FCD, indicating that our method is able to reliably measure the FCD of IVD tissues. Moreover, the slope of the curve-fitted line constrained to pass through the origin (slope = 1.09) is close to the theoretical value of 1, further demonstrating that the FCD of IVD tissues may be measured using the electrical conductivity approach.

Figure 4.

Correlation between FCD values measured using conductivity method and those estimated from GAG content and Eq. (12). For both AF and NP, n=15. The theoretical value of the slope is 1. For both linear curve-fits (passing through the origin and not), there is a strong correlation between measured and estimated values (R2 = 0.84 and R2 = 0.87, respectively).

It should be noted that, while the estimation of FCD from GAG content using Eq. (12) assumes that there are 2 moles of charge per mole of GAG, there are actually two types of dissacharides in IVD tissues contributing to the FCD: chondroitin sulfate (CS), which carries two negative charges per disaccharide, and keratan sulfate (KS), which has only one charged group per disaccharide. Previous studies have shown that disc PGs contain greater quantities of KS than those in articular cartilage.57 Furthermore, it has been shown that, for human IVD tissue, the ratio of KS to CS varies across the disc.60;61 Consequently, in order to accurately calculate the FCD from GAG content, the ratio of KS to CS in the tissue must be known and accounted for in Eq. (12). This difference likely contributed to the discrepancy in the measured and estimated values of FCD shown in Figure 4.

In addition to calculating values for FCD in IVD tissues, the two-point conductivity method is also able to estimate values for the diffusivity of Cl− (or K+) ions in the disc tissue. For AF tissue, the value was determined to be 7.56 ± 2.12 × 10−10 m2/sec (n=15), which corresponds to a relative diffusivity (i.e., the ratio of the diffusivity in tissue to that in aqueous solution) of 0.47 ± 0.13. The Cl− ion diffusivity in NP tissues was 1.03 ± 0.16 × 10−9 m2/sec (n=15), corresponding to a relative diffusivity of 0.64 ± 0.10. Previous studies have shown that, for small solutes, diffusivity in cartilaginous tissues and IVD is approximately 35 – 60% of that in aqueous solution.5;20;29;30;47;60 The results found here are in agreement with those in the literature for diffusivity of ions in IVD tissues.20;29 The slightly higher value for NP tissues is likely due to the higher water content of the tissue, as diffusivity has been shown to be dependent upon tissue hydration.20;47

As noted previously, several methods can be found in the literature for measuring the fixed charge density of cartilaginous tissues. The tracer cation method,48 which has been considered a “gold standard,” has not been readily adopted in regular laboratories, due to the use of potentially hazardous radiochemicals. Furthermore, several of the alternative techniques reported require the use of expensive equipment for obtaining FCD measurements. The method presented in this study is not only safe and reliable, but it is also easy to perform without special equipment. Therefore, we believe the two-point electrical conductivity approach represents a viable alternative technique for measuring FCD of cartilaginous tissues.

In summary, a new technique for measuring the fixed charge density of IVD tissue using a two-point conductivity approach has been developed. Using this new method, it was determined that the FCD of AF tissue is significantly lower than that in NP tissue, which is in agreement with previous studies. Furthermore, the analysis of GAG content, and its strong correlation with FCD measurements, indicates that the new technique is able to measure FCD reliably in IVD tissues. This study provides a dependable and straightforward alternative to current methods for measuring the FCD in disc tissue. Better understanding of the fixed charge density in IVD tissues is important for elucidation of tissue transport and mechanical behaviors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was supported by the grant number AR050609 from NIH NIAMS.

Contributor Information

Alicia R. Jackson, Tissue Biomechanics Laboratory, Dept. of Biomedical Engineering, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL 33146.

Tai-Yi Yuan, Tissue Biomechanics Laboratory, Dept. of Biomedical Engineering, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL 33146.

Chun-Yuh Huang, Stem Cell and Mechanobiology Laboratory, Dept. of Biomedical Engineering, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL 33146.

Wei Yong Gu, Tissue Biomechanics Laboratory, Dept. of Biomedical Engineering, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL 33146.

Reference List

- 1.Bashir A, Gray ML, Hartke J, et al. Nondestructive imaging of human cartilage glycosaminoglycan concentration by MRI. Magn Reson.Med. 1999;41:857–865. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199905)41:5<857::aid-mrm1>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckstein JC, Sen S, Schaer TP, et al. Comparison of animal discs used in disc research to human lumbar disc. Spine. 2008;33:E166–E173. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318166e001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkenblit SI, Frank EH, Salant EP, et al. Nondestructive detection of cartilage degeneration using electromechanical surface spectroscopy. J Biomech Eng. 1994;116:384–392. doi: 10.1115/1.2895788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckwalter JA. Aging and degeneration of the human intervertebral disc. Spine. 1995;20:1307–1314. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199506000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burstein D, Gray ML, Hartman AL, et al. Diffusion of small solutes in cartilage as measured by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and imaging. J Orthop Res. 1993;11:465–478. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100110402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CT, Fishbein KW, Torzilli PA, et al. Matrix fixed-charge density as determined by magnetic resonance microscopy of bioreactor-derived hyaline cartilage correlates with biochemical and biomechanical properties. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1047–1056. doi: 10.1002/art.10991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SS, Falcovitz YH, Schneiderman R, et al. Depth-dependent compressive properties of normal aged human femoral head articular cartilage: relationship to fixed charge density. Osteoarthritis.Cartilage. 2001;9:561–569. doi: 10.1053/joca.2001.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenberg SR, Grodzinsky AJ. Swelling of articular cartilage and other connective tissues: electromechanochemical forces. J Orthop Res. 1985;3:148–159. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100030204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eyre DR, Benya P, Buckwalter J, et al. Intervertebral disk: Basic science perspectives. In: Frymoyer JW, Gordon SL, editors. New Perspectives on Low Back Pain. Park Ridge, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1989. pp. 147–207. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farndale RW, Sayers CA, Barrett AJ. A direct spectrophotometric microassay for sulfated glycosaminoglycans in cartilage cultures. Connect.Tissue Res. 1982;9:247–248. doi: 10.3109/03008208209160269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank EH, Grodzinsky AJ, Koob TJ, et al. Streaming potentials: a sensitive index of enzymatic degradation in articular cartilage. J.Orthop.Res. 1987;5:497–508. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu WY, Justiz MA. Apparatus for measuring the swelling dependent electrical conductivity of charged hydrated soft tissues. J Biomech Engng. 2002;124:790–793. doi: 10.1115/1.1516571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu WY, Justiz MA, Yao H. Electrical conductivity of lumbar annulus fibrosis: Effects of porosity and fixed charge density. Spine. 2002;27:2390–2395. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200211010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu WY, Lai WM, Mow VC. Theoretical basis for measurements of cartilage fixed-charge density using streaming current and electro-osmosis effects. ASME Adv in Bioengng BED. 1993;26:55–58. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu WY, Lewis B, Saed-Nejad F, et al. Hydration and true denstiy of normal and PG-depleted bovine articular cartilage. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 1997;22:826. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu WY, Lewis B, Lai WM, et al. A technique for measuring volume and true density of the solid matrix of cartilaginous tissues. Advances in Bioengineering, ASME BED. 1996;33:89–90. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu WY, Mao XG, Foster RJ, et al. The anisotropic hydraulic permeability of human lumbar anulus fibrosus. Influence of age, degeneration, direction, and water content. Spine. 1999;24:2449–2455. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199912010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu WY, Mao XG, Rawlins BA, et al. Streaming potential of human lumbar anulus fibrosus is anisotropic and affected by disc degeneration. J Biomech. 1999;32:1177–1182. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu WY, Yao H. Effects of hydration and fixed charge density on fluid transport in charged hydrated soft tissue. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2003;31:1162–1170. doi: 10.1114/1.1615576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu WY, Yao H, Vega AL, et al. Diffusivity of ions in agarose gels and intervertebral disc: Effect of porosity. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2004;32:1710–1717. doi: 10.1007/s10439-004-7823-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guiot BH, Fessler RG. Molecular biology of degenerative disc disease. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:1034–1040. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200011000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasegawa I, Kuriki S, Matsuno S, et al. Dependence of electrical conductivity on fixed charge density in articular cartilage. Clin Orthop. 1983:283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helfferich F. Ion Exchange. New York: McGraw Hill Book Company, Inc; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendry NGC. The hydration of the neucleus pulposus and its relation to intervertebral disc derangement. J Bone Joint Surg. 1958;40 B:132–144. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.40B1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hickey DS, Hukins DWL. Relation between the structure of the annulus fibrosus and the function and failure of the intervertebral disc. Spine. 1980;5:106–116. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198003000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iatridis JC, MacLean JJ, O'Brien M, et al. Measurement of proteoglycan and water content distribution in human lumbar intervertebral discs. Spine. 2007;32:1493–1497. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318067dd3f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Insko EK, Clayton DB, Elliott MA. In vivo sodium MR imaging of the intervertebral disk at 4 T. Acad Radiol. 2002;9:800–804. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson AR, Travascio F, Gu WY. Effect of mechanical loading on electrical conductivity in human intervertebral disk. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131:054505. doi: 10.1115/1.3116152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson AR, Yao H, Brown MD, et al. Anisotropic ion diffusivity in intervertebral disc: an electrical conductivity approach. Spine. 2006;31:2783–2789. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000245842.02717.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson AR, Yuan TY, Huang CY, et al. Effect of compression and anisotropy on the diffusion of glucose in annulus fibrosus. Spine. 2008;33:1–7. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnstone B, Urban JP, Roberts S, et al. The fluid content of the human intervertebral disc. Comparison between fluid content and swelling pressure profiles of discs removed at surgery and those taken postmortem. Spine. 1992;17:412–416. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199204000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katchalsky A, Curran PF. Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics in Biophysics. 4th printing ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelsey JL, Mundt DF, Golden AL. Epidemiology of low back pain. In: Malcolm JIV, editor. The Lumbar Spine and Back Pain. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1992. pp. 537–549. ed. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koneshan S, Rasaiah JC, Lynden-Bell RM, et al. Solvent structure, dynamics, and ion mobility in aqueous solution at 25°C. J Phys Chem. 1998;102:4193–4204. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraemer J, Kolditz D, Gowin R. Water and electrolyte content of human intervertebral discs under variable load. Spine. 1985;10:69–71. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198501000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lai WM, Hou JS, Mow VC. A triphasic theory for the swelling and deformation behaviors of articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng. 1991;113:245–258. doi: 10.1115/1.2894880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le NA, Fleming BC. Measuring fixed charge density of goat articular cartilage using indentation methods and biochemical analysis. J Biomech. 2008;41:715–720. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lesperance LM, Gray ML, Burstein D. Determination of fixed charge density in cartilage using nuclear magnetic resonance. J Orthop Res. 1992;10:1–13. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu XL, Miller C, Chen FH, et al. The generalized triphasic correspondence principle for simultaneous determination of the mechanical properties and proteoglycan content of articular cartilage by indentation. J Biomech. 2007;40:2434–2441. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu XL, Sun DD, Guo XE, et al. Indentation determined mechanoelectrochemical properties and fixed charge density of articular cartilage. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:370–379. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000017534.06921.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lundon K, Bolton K. Structure and function of the lumbar intervertebral disk in health, aging, and pathologic conditions. J Orthop Sports Phys.Ther. 2001;31:291–303. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2001.31.6.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marchand F, Ahmed AM. Investigation of the laminate structure of lumbar disc annulus fibrosus. Spine. 1990;15:402–410. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199005000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maroudas A. Biophysical chemistry of cartilaginous tissues with special reference to solute and fluid transport. Biorheology. 1975;12:233–248. doi: 10.3233/bir-1975-123-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maroudas A. Physicochemical properties of cartilage in the light of ion exchange theory. Biophys.J. 1968;8:575–595. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(68)86509-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maroudas A. Physicochemical properties of articular cartilage. In: Freeman MAR, editor. Adult Articular Cartilage. Pitman Medical; 1979. pp. 215–290. ed. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maroudas A, Muir H, Wingham J. The correlation of fixed negative charge with glycosaminoglycan content of human articular cartilage. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 1969;177:492–500. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(69)90311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maroudas A, Stockwell RA, Nachemson A, et al. Factors involved in the nutrition of the human lumbar intervertebral disc: cellularity and diffusion of glucose in vitro. J Anat. 1975;120:113–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maroudas A, Thomas H. A simple physicochemical micromethod for determining fixed anionic groups in connective tissue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;215:214–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Minassian A, O'Hare D, Parker KH, et al. Measurement of the charge properties of articular cartilage by an electrokinetic method. J Orthop Res. 1998;16:720–725. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Narmoneva DA, Wang JY, Setton LA. A noncontacting method for material property determination for articular cartilage from osmotic loading. Biophys.J. 2001;81:3066–3076. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75945-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.NIH. Research on low back pain and common spinal disorders. NIH Guide. 1997;26 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palmer AW, Guldberg RE, Levenston ME. Analysis of cartilage matrix fixed charge density and three-dimensional morphology via contrast-enhanced microcomputed tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19255–19260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606406103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Panagiotacopulos ND, Pope MH, Bloch R, et al. Water content in human intervertebral discs. Viscoelastic behavior. Spine. 1987;12(Part II):918–924. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198711000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Panagiotacopulos ND, Pope MH, Krag MH, et al. Water content in human intervertebral discs. Measurement by magnetic resonance imaging. Spine. 1987;12(Part I):912–917. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198711000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perie D, Iatridis JC, Demers CN, et al. Assessment of compressive modulus, hydraulic permeability and matrix content of trypsin-treated nucleus pulposus using quantitative MRI. J Biomech. 2006;39:1392–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shapiro EM, Borthakur A, Gougoutas A, et al. 23Na MRI accurately measures fixed charge density in articular cartilage. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:284–291. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stevens RL, Ewins RJ, Revell PA, et al. Proteoglycans of the intervertebral disc. Homology of structure with laryngeal proteoglycans. Biochem J. 1979;179:561–572. doi: 10.1042/bj1790561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Urban JP, Maroudas A. Swelling of the intervertebral disc in vitro. Connect Tissue Res. 1981;9:1–10. doi: 10.3109/03008208109160234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Urban JP, McMullin JF. Swelling pressure of the intervertebral disc: influence of proteoglycan and collagen contents. Biorheology. 1985;22:145–157. doi: 10.3233/bir-1985-22205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Urban JPG. PhD Dissertation. London, UK: London University; 1977. Fluid and solute transport in the intervertebral disc. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Urban JPG, Maroudas A. The chemistry of the intervertebral disc in relation to its physiological function and requirements. Clinics in Rheumatic Diseases. 1980;6:51–77. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wheaton AJ, Casey FL, Gougoutas AJ, et al. Correlation of T1rho with fixed charge density in cartilage. J Magn Reson.Imaging. 2004;20:519–525. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.White AA. Biomechanics of lumbar spine and sacroiliac articulation: relevance to idiopathic low back pain. In: White AA, Gordon SL, editors. Symposium on Idiopathic Low Back Pain; CV Mosby Co.; St. Louis. 1981. pp. 296–322. [Google Scholar]