Abstract

New developments and expanding indications have resulted in a significant increase in the number of patients with pacemakers and internal cardioverterdefibrillators (ICDs). Because of its unique capabilities, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become one of the most important imaging modalities for evaluation of the central nervous system, tumours, musculoskeletal disorders and some cardiovascular diseases. As a consequence of these developments, an increasing number of patients with implanted devices meet the standard indications for MRI examination. Due to the presence of potential life-threatening risks and interactions, however, pacemakers and ICDs are currently not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in an MRI scanner. Despite these limitations and restrictions, a limited but still growing number of studies reporting on the effects and safety issues of MRI and implanted devices have been published. Because physicians will be increasingly confronted with the issue of MRI in patients with implanted devices, this overview is given. The effects of MRI on an implanted pacemaker and/or ICDs and vice versa are described and, based on the current literature, a strategy for safe performance of MRI in these patients is proposed. (Neth Heart J 2010;18:31-7.)

Keywords: magnetic resonance imaging, pacemaker, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

As a result of new developments and expanding indications,1-3 an increasing number of patients are treated with implantable cardiac systems, including pacemakers, loop recorders and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs).4,5

At the same time, the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as diagnostic imaging modality has increased enormously.6 MRI has become an important tool in evaluating the central nervous system, tumours, musculoskeletal disorders and cardiovascular diseases. MRI is noninvasive, does not require exposure to radiation, enables three-dimensional visualisation of anatomic structures, and is superior in displaying soft tissue contrast. For evaluation of heart disease, cardiac MRI offers unique features including highly accurate quantification of ventricular function,7,8 assessment of perfusion and viability,9 localisation of scar tissue,10 quantification and timing of intramural myocardial contraction,11 and the prospect of vulnerable plaque detection.12

Both developments have resulted in an increasing number of patients with implanted devices who meet indications for an MRI examination. Unfortunately, these patients are not allowed to undergo an MRI examination, given the potential detrimental effects of an MRI scanner on such a device. It is estimated that at least 200,000 cardiac device patients were denied an MRI scan in 2004, indicating the magnitude of this problem.13

Despite the restriction, undersigned by the Food and Drug Administration and all the manufacturers of implantable devices, several individual cases and a limited number of animal and human studies have been published reporting on the effects and safety of MRI and devices. Recently, a position paper on this topic was published, stating that on a case-by-case basis, the diagnostic benefit from MRI may outweigh the risks for some pacemaker and ICD patients.14

In this overview, the effects of MRI on an implanted pacemaker or ICD and vice versa will be described, and a strategy for safe performance of MRI in these patients is proposed. For clinical relevance, only results from studies performed with MRI scanners operating at 1.5 Tesla will be described, because this is the most widely used type of clinical scanner.

Basic principles of MRI

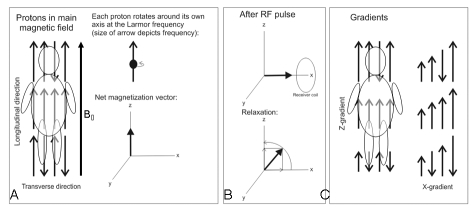

In order to appreciate why MRI applied in patients with implanted devices is potentially hazardous, fundamental knowledge on some of the technical aspects of this imaging technique is required. Therefore, a brief description of the basic principles of MRI will be provided (see also figure 1).

Figure 1.

A) The strong static magnetic (B0) field aligns the normally randomised oriented hydrogen nuclei (protons) in the human body, causing a net longitudinal magnetisation. In this situation, the protons rotate at a predefined frequency, the Larmor frequency. B) The radiofrequency (RF) pulse flips the net longitudinal magnetisation into the transverse plane (upper part). After the RF pulse is switched off, the original situation is restored. The transverse magnetisation will fade and a progressive increase in the longitudinal magnetisation will occur (lower part). C) Magnetic gradient fields alter the longitudinal magnetisation in a linear way along the axis causing small changes of the Larmor frequency of the protons. This enables the identification of proton position in 3D space.

To create an image of a desired part or structure (for example brain, heart, coronary arteries) of the human body using the nuclear magnetic resonance technique, a signal from resonating protons located in this particular part of interest of the body has to be acquired. To achieve this, an MRI scanner applies a strong static magnetic field (ranging from 0.5 to 3 Tesla for human studies; 1.5 Tesla equals ≈ 30,000 times the earth magnetic field). Today, most clinical MRI scanners operate at 1.5 Tesla. A static magnetic field (B0) is required to align the randomly oriented hydrogen nuclei (protons) in the human body. This is necessary to generate a net (longitudinal) magnetisation within the body (figure 1A) and to make the protons rotate at a predefined frequency, the Larmor frequency.

A radiofrequency (RF) pulse with the Larmor frequency of a certain duration is applied to bring the protons in resonance and flip the net longitudinal magnetisation into the transverse plane (figure 1B). The transverse magnetisation induces a current in a receiver coil, placed on the body.

After switching off the RF pulse, fading of the transverse magnetisation and a progressive increase in the longitudinal magnetisation will occur, and the original situation (only net longitudinal magnetisation within the body) is restored.

This process of fading of transverse magnetisation and increase in longitudinal magnetisation is specific for different types of tissue and therefore allows the generation of image contrast between different structures.

Fast switching magnetic gradient fields are required for spatial encoding of the magnetic resonance signal. They alter the longitudinal magnetisation in a linear way along the axis of the gradient coil (figure 1C). This results in small changes in the Larmor frequency of the protons and enables the identification of proton position in 3D space.

All these components, i.e. the strong static magnetic field, the switching on and off of the gradients, the repeated RF pulses, and their combination, may have specific detrimental effects on an implanted device and may cause harm to patients undergoing MRI examinations.

These effects can be categorised either by the MRI individual component-related effects on the device, or by the type of the effect on the device. The latter is considered to have more clinical relevance and is summarised below.

Effects of MRI on devices

Mechanical effects

As a result of the strong static magnetic field, objects containing iron (Fe) are attracted by the scanner. Besides iron, cobalt (Co), nickel (Ni), and a few alloys are also strongly magnetic. Implantable devices usually contain a small amount of one or more of these metals and are considered to be ferromagnetic. Therefore, there is the possibility of movement of the implanted pacemaker.

The highest force and torque experienced by devices is found to be at the entrance to the scanner near its edges and inside the bore.

The current devices are smaller and contain only a limited amount of ferromagnetic material. As a result, the force and torque are nowadays limited, varying between 0.05 and 3.6 Newton (N) for pacemakers, and from 1 to 5.9 N for ICDs, depending on the year the device was manufactured. In general, newgeneration ICDs experience ten times higher magnetic force and torque than pacemakers. However, this is still far below the gravity of the earth (9.81 N/kg).15,16 For reference, forces <2 N will not be felt by patients,15 and there are no reports on complaints of pain or a sensation of pulling during an MRI scan.17,18 Based on these observations, the newer-generation pacemakers and ICDs are not considered to present any safety risks with respect to magnetic force and torque while older pacemakers and (larger) ICDs may cause problems.

Induction effects: sensing and pacing

The static magnetic field may have direct implications on pacemaker functioning, such as causing unpredictable intermittent reed switch activity, leading to either asynchronous pacing (reed switch closed) or unwanted inhibition of pacing in the presence of an open reed switch.

Electronic circuits may be damaged. Communication between device and external programmer may be affected or become impossible.

The gradient magnetic fields may induce currents in the leads. This may result in oversensing or undersensing, with the danger of inappropriate high rate pacing, or inhibition of pacing. The induced currents could also possibly induce life-threatening arrhythmias. Besides the gradients, the pulsed RF field may also induce high-rate pacing caused by oversensing.

Exposure to the electromagnetic field applied by the MRI scanner may also directly affect or modify the electronic circuits and functional settings of the implanted device.

Some of these deleterious effects on device functioning can be avoided by reprogramming the device to the asynchronous mode or by reprogramming all therapies to ‘off’. This requires close patient monitoring during an MRI examination.

One of the serious dangers is the (unnoticed) reset of the device during the scan procedure. Unwanted activation of standard device settings may occur, carrying the risk of inhibition of pacing or even inappropriate shock therapy.

In ICDs, the fast switching magnetic gradients can mimic intrinsic cardiac activity which may be interpreted as ventricular tachycardia (oversensing) with inappropriate therapy delivery (shocks) as a result. Table 1 provides a summary of the potential adverse interactions between MRI and devices.

Table 1.

MRI and devices: potential adverse interactions.

| 1. Lead heating; loss of capture |

| 2. Induction of ventricular tachycardia |

| 3. Rapid atrial pacing |

| 4. Reed switch malfunction |

| 5. Asynchronous pacing |

| 6. Inhibition of pacing |

| 7. Alteration of programming |

| 8. Inappropriate ICD therapy (oversensing) |

| 9. Loss of communication with external programmer |

Induction effects: lead heating

Lead heating is currently considered one of the major risk factors of MRI in patients with implanted devices. It is important to realise that lead-specific risks are also relevant for abandoned leads, regardless of whether they are capped or otherwise electrically intact.

The RF field may induce current (energy) in the lead system which functions as an antenna. The tissue near the lead tip has limited conductivity, and therefore the energy in the lead will be converted to heat at the lead tip.19 This effect may cause thermal damage including formation of oedema and scar tissue. As a result, increasing stimulation thresholds, and finally (unpredictable) loss of capture may occur.

The possibility and amount of heating is determined by a wide range of factors including the length and location of the lead, the conductivity of lead material, the position of the subject and lead within the scanner, the type of pulse sequence used, and the anatomical object of scanning. Blood flowing around the tip acts as a coolant, and is therefore also considered a determinant of lead heating.

Animal and in vitro studies

In an animal study by Luechinger et al., it was demonstrated that an increase in lead temperature of up to 20°C may occur within seconds after initialisation of the scanning procedure.20 In this study, nine pigs with chronically implanted pacemaker systems were studied using a 1.5 Teslan MRI scanner. To provoke heating, a pulse sequence was applied that resulted in a high specific absorption rate (SAR; measure of the absorption of electromagnetic energy in the body) of 3.8 W/kg. For reference, the SAR of a cellular phone is below 0.75 W/kg. In general, the SAR limit for humans is 2 W/kg. Besides the temporary increase in lead temperature, also a significant increase in lead impedance up to two weeks post-MRI was observed. However, only minor changes in stimulation thresholds occurred and no evidence for heat-induced damage was found at pathological examination.

The effects of MRI on ICDs were studied in a dog model.15 Eighteen mongrel dogs were studied four weeks after implantation using a 1.5 T scanner. The imaging protocol consisted of most clinically used pulsed sequences (SAR <1.4 W/kg) and an imaging protocol resulting in a high SAR (≈3.5 W/kg). The devices were in monitor-on /therapy-off mode during the scan procedure. No arrhythmias occurred during scanning. However, all the ICDs interpreted noise during the scanning as ventricular fibrillation. The maximum lead heating was 0.2°C with the maximum energy protocol. However, in one animal loss of capture occurred directly after scanning which persisted for 12 hours. The other animals showed no changes in thresholds. Histopathological analysis demonstrated only limited fibrosis or necrosis which was comparable with the control animals not undergoing an MRI study.

In the same study, also in vitro experiments were performed to determine the amount of lead heating as a result of MRI. Using the scan protocol with high SAR levels, heating up to 35°C was found. However, this was related to the depth (3 to 4 cm) to which the leads were placed in the gel (polyacrylamide), simulating the electric and heat conductivities of tissue. The clinical pulse sequences resulted in an increase of 3.9°C. When the leads were placed only 2–3 mm deep in the gel, which is comparable with the real clinical situation, no significant heating was observed (0.2–7.2°C).

In vivo studies

Recently, several studies were published, describing the effects of 1.5T scanning in pacemaker and ICD patients. A summary is provided in table 2.

Table 2.

| Study | Year | Patients | No. scans | Scanner | Thoracic scan | SAR (W/kg) | Pacemaker dependent | Reprogramming | Effects | SAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martin et al.21 | 2004 | 54 | 64 | 1.5T | Partly | ≤2 | No | None | Δ threshold | None |

| Schiemdel et al.22 | 2005 | 45 | 63 | 1.5T | None | ≤1.2 | No | Asynchronous | None | None |

| Sommer et al.23 | 2006 | 82 | 115 | 1.5T | None | ≤1.5 | No | Asynchronous (<60 bpm) Sense only (>60 bpm) | Δ threshold/ troponint↑ | None |

| Gimbel et al.24 | 2005 | 46 | 60 | 1.5T | None | ≤2 | Yes | Asynchronous | Δ threshold | None |

| Nazarian et al.25 | 2006 | 12 | 15 | 1.5T | Partly | ≤2 | Yes | Asynchronous | None | None |

| Nazarian et al.25 | 2006 | 24 | 24 | 1.5T | Partly | ≤2 | ICD | Switched off | None | None |

| Gimbel et al.26 | 2005 | 7 | 8 | 1.5T | None | Unknown | ICD | Therapies ‘off, Detections ‘on’ | 1×POR | None |

SAR+ specific absorption rate, SAE=severe adverse effect, POR=power on reset.

Pacemaker-independent patients

Martin et al. suggested that MRI scanning could be performed safely.21 Fifty-four pacemaker-independent patients underwent in total 64 MRI scans. The great majority of patients underwent noncardiac MRI examinations. No changes in lead impedance or battery voltages were observed, and no loss of capture occurred. In approximately one third of the leads changes in thresholds occurred, but this was considered significant, although clinically irrelevant, in only 10%. Change in output was only required in 1.9%. The threshold changes were not related to cardiac chamber, anatomical location, time from implantation, or highest SAR level.

In a study by Schiemdel et al., pacemaker functioning was evaluated in 45 patients who all underwent a brain scan (63 examinations in total).22 The pacemakers were reprogrammed in an asynchronous mode and patients were monitored during the scan procedure using pulse oximetry. The maximum SAR was limited to 1.2 W/kg. All scans were completed without complications. Pacemaker functioning was evaluated prior to and directly after the MRI scan, and at threemonth follow-up. No significant changes in thresholds were observed after the scan procedure.

The largest study to date is from Sommer and coworkers.23 They studied 82 pacemaker patients who underwent a total of 115 extrathoracic MRI examinations at 1.5 T. All patients were pacemakerindependent and all devices came from the same manufacturer (Medtronic).

The maximum SAR was limited to 1.5 W/kg. The pacemakers were programmed in asynchronous mode if the heart rate was <60 beats/min, or in the senseonly mode if the heart rate was >60 beats/min. The atrial pacing capture threshold was significantly increased directly after the scan procedure from 0.94±0.39 V to 0.98±0.41 V (p<0.0017). Serum troponin I was used as an indicator for tip heatingrelated injury. In four patient examinations, a rise in troponin I to above normal levels was found. A significant rise in troponin I to 0.16 ng/ml was only observed in one patient; this was associated with a significant rise in threshold.

Pacemaker-dependent patients

Pacemaker-dependent patients subjected to MRI were studied by Gimbel et al.20 From 1994 to 2004, 46 pacemaker patients underwent 60 MRI scans using a 1.5 T system. Of these, ten patients were pacemaker dependent and underwent in total 11 MRI scans using a head coil (10 head scans, 1 cervical spine). Only conventional spin echo pulse sequences were applied (maximum SAR 1–2 W/kg).

All devices were reprogrammed to VOO or DOO at 60 ppm prior to the scan procedure. Pacemaker functioning was evaluated directly after the scan procedure and at three-month follow-up. No symptoms were reported during the MRI scan. Only one patient had a temporary rise in threshold of 0.5 V directly after the scan procedure, which had returned to baseline at three-month follow-up. Three patients showed an increase in threshold of 0.5V at threemonth follow-up (2 atrial leads, 1 ventricular lead).

Pacemaker-dependent patients were also evaluated by Nazarian et al.25 In this study, only patients were included with systems that were already shown to be MRI safe by in vitro phantom and in vivo animal studies.

Of 55 pacemaker patients, 12 were pacemaker dependent. These pacemaker-dependent patients underwent in total 15 different MRI examinations, including extrathoracic and thoracic scans. Pacemakers were programmed in the asynchronous mode and the SAR was limited to 2.0 W/kg. All scans were completed uneventfully, and no pacemaker malfunctioning was reported. This study represents what is currently the largest series of patients undergoing thoracic and cardiac MRI scans (n=29). All the extrathoracic examinations and the great majority of the thoracic examinations (93%) were of good enough quality to address the diagnostic questions.

ICD patients

Nazarian and cowokers also reported the largest series of ICD patients (n=24) who were subjected to MRI examination.25 All ICD therapy options were switched off during the MRI examination. No programming changes or malfunctioning were noted after the scan.

Safe scanning of ICD patients was also reported by Gimbel et al.26 In seven ICD patients post MR scan no changes in pacing capabilities, sensing, impedances, charge times or battery status were found.

In the most recent publication (2009), 18 ICD patients underwent 18 MRI scans.27 The devices were reprogrammed to arrhythmia detection ‘on’ and therapy mode ‘off’. No significant changes in pacing threshold, lead impedance or rise in troponin I were observed. However, in two patients, oversensing due to RF noise occurred. In both cases, the RF noise was interpreted by the ICD as ventricular fibrillation. Because the devices were programmed in ‘therapy-off’ mode and no device reset had taken place, no (inappropriate) shocks were given.

A significant reduction in battery voltage was found after the scan procedure.

Because of the limited sample sizes, the variability in implantable devices, scanners and pulse sequences used, the expected normal variance in thresholds and the lack of control groups, no firm conclusions should be drawn from these investigations. Nevertheless, no serious adverse events were observed in over 120 (mostly noncardiac) MRI examinations in over 100 patients.

Effects of devices on image quality

The presence of a device may induce image artifacts. However, there are no specific studies available except the one from Roguin et al. with respect to the effect of the devices on image quality.15 Image distortion is strongly dependent on selected image planes and used pulse sequences. It was observed that fast spin echo sequences and steady state free-precession (SSFP) sequences were more prone to distortion artifacts. This might have consequences for studying anatomy and especially cardiac function since the SSFP sequence is the working horse for studying cardiac function. Fastgradient recalled echo, tagging and fast-spoiled gradient recalled echo sequences, however, do provide good image quality.

Artifacts seem to be larger in image planes parallel to planes defined by the device itself and image distortion was the largest at a 10 to 15 cm distance from the device.15 In clinical practice, only image planes including the area where the device is located may demonstrate image artifacts in the direct neighbourhood of the device.

Recommendations for scanning

Recommendations for performing an MRI scan in a pacemaker or ICD patient are listed in table 3. Scanning should only be performed after a risk-benefit assessment in an expert centre with full pacing facilities available. Clear instructions and explanation of the risks should be given and informed consent should be obtained from the patient. Adequate patient monitoring using continuous ECG and pulse oximetry during imaging is necessary, and the presence of advanced cardiac life support equipment and personnel on site are mandatory. The use of transmit/receive coils and limitation of SAR values reduce the risk of RF-induced thermal damage. Evaluation of device functioning prior to and directly after the scan procedure and at 6 to 12 weeks follow-up is indicated. An increase in output to submaximum level might be considered. Because of the risk of more severe complications, patients with high thresholds prior to scanning and pacemaker-dependent patients should be excluded from MRI.

Table 3.

Safety measures for MRI in pacemaker patients.

| 1. Verify that MRI is clinically necessary and that the benefit outweighs the risk |

| 2. Obtain full written informed consent |

| 3. Pacemaker-independent patients only |

| 4. Advanced Cardiac Life Support equipment and personnel direct available / on site |

| 5. Reprogramming of pacemaker is recommended for the duration of scanning: lead to bipolar mode, disable the minute ventilation feature |

| 6. Increase output to submaximum level; if required output is already (sub)maximum, do not perform MRI |

| 7. Continuous ECG monitoring |

| 8. Pulse oximetry monitoring |

| 9. Reduce SAR; reduction in SAR can be achieved by increasing the repetition time or field of view, and/or reducing the flip angle or the acquisition bandwidth |

| 10. Evaluate device functioning direct after MRI scanning and at 6–12 weeks follow-up |

Future perspective

Several new developments have focused on the problems induced by the application of MRI in pacemaker patients.

Devices are made more resistant to magnetic interference and specially designed MRI safety modes have been incorporated that change the pacemaker settings automatically in favour of an MRI scan (lead to bipolar mode; minute ventilation feature disabled, output increased to (sub)maximum level).

Fibre-optic pacing leads are proposed as an alternative to conventional leads. This type of lead is not affected by the magnetic field and lead heating does not occur.28 However, despite these initial promising results, this type of lead is only used in an experimental set-up and has not entered the clinical arena yet. A limitation is that a specially designed pulse generator which drives a laser is also required.

Recently, the first prospective, randomised, multicentre study was conducted to test a specially designed MRI-conditional pacemaker system.29 In over 200 patients an MRI scan was performed to image the brain and spine. No MRI scan-related complications were observed.

These developments offer the prospect to study patients with an implanted device more safely by MRI.

Methods and software to more accurately and more uniformly determine the SAR distribution within the body are required to compare effects of adapted and newly designed pulse sequences on different models and devices from different manufacturers.

Conclusions

Up to now, the presence of a pacemaker and/or ICD remains a contraindication for MRI. However, it has been demonstrated that with appropriate patient selection and precautions, MRI can be performed relatively safely. However, currently no pacemakers or ICDs except one pacemaker system have industry or Food and Drug Administration clearance for MRI compatibility.

Currently, lead heating and its related consequences including the formation of oedema and/or scar tissue causing increased thresholds or even loss of capture, seems to be a larger problem than the device functioning in an MR environment. Therefore, pacemaker/ICD patients cannot undergo an MRI scan safely and on a routine basis until the problem of lead heating is resolved.

References

- 1.Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J, Krueger S, Kass DA, De Marco T, et al; Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing, and Defibrillation in Heart Failure (COMPANION) Investigators. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2140–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamas GA, Orav EJ, Stambler BS, Ellenbogen KA, Sgarbossa EB, Huang SK, et al. Quality of life and clinical outcomes in elderly patients treated with ventricular pacing as compared with dualchamber pacing. Pacemaker selection in the elderly investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996:336:1097–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connolly SJ, Kerr C, Gent M, Roberts RS, Yusuf S, Gillis AM, et al. Effects of physiologic pacing versus ventricular pacing on the risk of stroke and death due to cardiovascular cause. Canadian trial of physiologic pacing investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1385–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverman BG, Gross TP, Kaczmarek RG, Hamilton P, Hamburger S. The epidemiology of pacemaker implantation in the United States. Public Health Rep. 1995;110:42–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maisel WH, Sweeney MO, Stevenson WG, Ellison KE, Epstein LM. Recalls and safety alerts involving pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator generators. JAMA. 2001;286:793–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rieder SJ. MR imaging: Its development and the recent Nobel prize. Radiology. 2004;231:638–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grothues F, Smith GS, Moon JC, Bellenger NG, Collins P, Klein HU, et al. Comparison of interstudy reproducibility of cardiovascular magnetic resonance with two-dimensional echocardiography in normal subjects and in patients with heart failure or left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grothues F, Moon JC, Bellenger NG, Smith GS, Klein HU, Pennell DJ. Interstudy reproducibility of right ventricular volumes, function, and mass with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Am Heart J. 2004;147:218–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcu CB, Beek AM, van Rossum AC. Clinical applications of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. CMAJ. 2006:10:911–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim RJ, Wu E, Rafael A, Chen EL, Parker MA, Simonetti O, et al. The use of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to identify reversible myocardial dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2000;16:1445–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zwanenburg JJM, Gotte MJW, Marcus JT, Kuijer JP, Knaapen P, Heethaar RM, et al. Propagation of onset and peak time of myocardial shortening in time of myocardial shortening in ischemic versus nonischemic cardiomyopathy: assessment by magnetic resonance imaging myocardial tagging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:2215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fayad ZA. The assessment of the vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque using MR imaging: a brief review. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2001;17:165–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalin R, Stanton MS. Current clinical issues for mri scanning of pacemaker and defibrillator patients. Pace. 2005;26:326–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roguin A, Schwitter J, Vahlhaus C, Lombardi M, Brugada J, Vardas P, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in individuals with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices. Europace. 2008;10:336–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roguin A, Zviman MM, Meininger GR, Rodrigues ER, Dickfield TM, Bluemke DA, et al. Modern pacemaker and implantable cardioverter/defibrillator systems can be magnetic resonance imaging safe. In vitro and invivo assessment of safety and function at 1.5T. Circulation. 2004;110:475–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luechinger R, Duru F, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P, Candinas R. Force and torque effects of a 1.5 Teslan mri scanner on cardiac pacemakers and ICD's. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2001;24:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sommer T, Vahlhaus C, Lauck G, von Smekal A, Reinke M, Hofer U, et al. MRI and cardiac pacemakers: in-vitro evaluation and invivo studies in 51 patients at 0.5T. Radiology. 2000;215:869–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duru F, Luechinger R, Candinas R. MRI in patients with cardiac pacemakers. Radiology. 2001;219:856–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walton C, Gergely S, Economides AP. Platinum pacemaker electrodes: origins and effects of the electrode-tissue interface impedance. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1987;10:87–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luechinger R, Zeijlemaker VA, Morre Pederson E, Mortensen P, Falk E, Duru F, et al. In vivo heating of pacemaker leads during magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J. 2004;26:376–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin ET, Coman JA, Shellock FG, Pulling CC, Fair R, Jenkins K. Magnetic resonance imaging and cardiac pacemaker safety at 1.5-Tesla. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmiedel A, Hackenbroch M, Yang A, Nähle CP, Skowasch D, Meyer C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain in patients with cardiac pacemakers. Experimental and clinical investigations at 1.5 Tesla. Rofo. 2005;177:731–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sommer T, Naehle CP, Yang A, Zeijlemaker V, Hackenbroch M, Schmiedel A, et al. Strategy for safe performance of extrathoracic magnetic resonance imaging at 1.5 Tesla in the presence of cardiac pacemakers in non-pacemaker-dependent patients: a prospective study with 115 examinations. Circulation. 2006;114:1285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gimbel JR, Baily SM, Tchou PJ, Ruggieri PM, Wilkoff BL. Strategies for the safe magnetic resonance imaging of pacemakerdependent patients. PACE. 2005;26:1041–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nazarian S, Roguin A, Zviman MM, Lardo AC, Dickfeld TL, Calkins H, et al. Clinical utility and safety of a protocol for noncardiac and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging of patients with permanent pacemakers and implantable-cardioverter defibrillators at 1.5 Tesla. Circulation. 2006;114:1277–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gimbel JR, Kanal E, Schwartz KM, Wilkoff BL. Outcome of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) in Selected Patients with Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators (ICDs). Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28:270–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naehle CP, Strach K, Thomas D, Meyer C, Linhart M, Bitaraf S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging at 1.5-T in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrllators. J Am Coll Card. 2009;54:549–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greatbatch W, Miller V, Shellock FG. Magnetic resonance safety testing of a newly-developed fiber-optic cardiac pacing lead. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;16:97–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sutton R, Kanal E, Wilkoff BL, Bello D, Luechinger R, Jeniskens I, et al. Safety of magnetic resonance imaging of patients with new Medtronic Enrhythm MRI SureScan pacing system: clinical study design. Trials. 2008;66:9;1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]