Abstract

One of the recent breakthroughs in stem cell research has been the reprogramming of human somatic cells to an embryonic stem cell (ESC)-like state (induced pluripotent stem cells, iPS cells). Similar to ESCs, iPS cells can differentiate into derivatives of the three germ layers, for example cardiomyocytes, pancreatic cells or neurons. This technique offers a new approach to investigating disease pathogenesis and to the development of novel therapies. It may now be possible to generate iPS cells from somatic cells of patients who suffer from vascular genetic diseases, such as hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT). The iPS cells will have a similar genotype to that of the patient and can be differentiated in vitro into the cell type(s) that are affected in the patient. Thus they will serve as excellent models for a better understanding of mechanisms underlying the disease. This, together with the ability to test new drugs, could potentially lead to novel therapeutic concepts in the near future. Here we report the first derivation of three human iPS cell lines from two healthy individuals and one HHT patient in the Netherlands. The iPS cells resembled ESCs in morphology and expressed typical ESC markers. In vitro, iPS cells could be differentiated into cells of the three germ layers, including beating cardiomyocytes and vascular cells. With this technique it will be possible to establish human cardiovascular disease models from patient biopsies provided by the principal hospitals in the Netherlands. (Neth Heart J 2010;18:51-4.)

Keywords: induced pluripotent stem cell, reprogramming, genetic cardiovascular disease, human embryonic stem cell, disease model, drug testing

One of the most exciting breakthroughs in stem cell research of the last couple of years has been the discovery that it is possible to reprogram somatic cells, for example from skin, to a developmental ‘ground state’ (induced pluripotent stem cells, iPS cells). This means that cells from an adult individual can be turned into pluripotent stem cells that are broadly indistinguishable from embryonic stem cells (ESCs) derived from early human embryos. In 2006, Takahashi and Yamanaka discovered that simply introducing four ‘pluripotency genes’ (genes identified previously as being prominently expressed in ESCs) into mouse skin cells made them immortal and able to form all cells in the body of an adult mouse.1 Previously, the only way to make somatic cells become pluripotent was by somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). This involves transferring a somatic cell nucleus into an unfertilised egg and then reisolating cells from the resulting embryo after a few days of culture. Human SCNT, also referred to as ‘therapeutic cloning’, is banned in many countries, including the Netherlands, since an embryo is created as an intermediate step. Since the first generation of iPS cells from human skin in 2007,2,3 this technology has become a robust way of obtaining pluripotent stem cells, not only from skin of healthy individuals but also from patients with specific (genetic) diseases.4 Much of the technology developed for characterising and inducing differentiation of human ESCs in culture has proven transferable to human iPS cells.5 In the context of the study of cardiovascular disease, this means it should be possible to derive pluripotent stem cells from tissue samples of specifically chosen patients, differentiate them into cardiovascular derivatives (cardiomyocytes, vascular endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells and possibly cells of the conduction system), and study the effects of the disease on the phenotype and physiology of those cells.6,7 A potential caveat is that differentiated stem cells in culture tend to be immature compared with their normal adult counterparts so the question will be whether the disease phenotype does in fact manifest, and this is an area currently subject to intense research.

Cardiovascular disease is still one of the leading causes of death in the Western world. Although deterioration in heart function can be initiated by multiple extrinsic factors (diet, high blood pressure, atherosclerosis and infarction), intrinsic factors (gene mutations, genetic variants leading to predisposition) are also known to underlie many of the cardiovascular diseases. For example, some patients suffering from long-QT syndrome have a mutation in a gene encoding the cardiac sodium ion channel, and can develop severe arrhythmias unexpectedly with a high risk of sudden cardiac death.8 In many cases, a combination of the genetic abnormality and extrinsic stimuli can precipitate onset of arrhythmia. To date mechanisms of genetic cardiovascular disease have mainly been studied in animal models, especially transgenic mice expressing ectopic genes or with specific gene mutations. Differences in the physiology of mouse and human hearts (with beat rates of 500 beats/min vs. 60 to 80 beats/min respectively being the most striking) are limiting aspects of the mouse as a good model of human cardiac diseases. The advent of iPS cell technology may now offer new models for disease physiology in the human heart and vascular system.

The four transcription factors used by Yamanaka for deriving human iPS cells from fibroblasts were OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 and C-MYC.2 Recent publications have now shown that cells from several different adult tissues can also be reprogrammed,9,10 and that depending on the endogenous expression profile of the starting cell population or the addition of chemicals or small molecules, c-myc (an oncogene) and also other factors may be dispensible for this process.11,12 In addition, intensive research is being conducted on reprogramming methods independent of DNA-integrating retrovirus or lentivirus (e.g. adenovirus or direct plasmid transfection).13,14 However, with all of these approaches, the reprogramming efficiencies remain low and the process is labour intensive. With whatever method used, the pluripotent state of the reprogrammed human cells must be demonstrated. This is typically achieved by confirming that the iPS cells express a gamut of markers normally associated with human ESCs, and the ability to form benign tumours (teratomas) in immunodeficient mice. The teratomas should consist of tissues arising from all three embryonic germ layers, such as cartilage, muscle, primitive neural cells and gastrointestinal tract tissue. In addition to the generation of human iPS cell lines that do not have any obvious genetic abnormalities, there are now multiple examples of iPS cell lines derived from patients with genetic diseases.4 By deriving the afflicted cell type from these iPS cells, it may be possible to study how the disease develops, and in the near future these differentiated cells could be used to screen new drugs and chemical compounds to inhibit disease progression. For example, an iPS cell line was recently derived from a patient with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA).15 SMA-patients suffer from selective loss of a certain type of motor neurons, resulting in life-threatening progressive muscular atrophy and weakness. The underlying cause of the disease is a mutation in the survival motor neuron 1 gene (SMN1). Although SMA-iPS cells initially produced similar numbers of motor neurons as wildtype iPS cells, at later time points they were fewer in number and were smaller in size. These initial experiments demonstrate that SMA-iPS can at least partly recapitulate features of the disease observed in vivo, and the iPS cell model may provide a platform for identifying compounds that prevent cell deterioration. In the long-term, patient-specific iPS could also be used in cell replacement therapies, for example, transplantation of iPSderived cardiomyocytes after cardiac infarction. However, there are still many issues to be solved before even the transplantation of embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes can occur.6,16 With patient-specific iPS cells, no rejection reaction would occur, because the transplanted cells would be immunologically identical to the individual.

We have now established human and mouse iPS cell technology in our laboratory, and have derived several human iPS cell lines from skin fibroblasts obtained from healthy individuals, and more recently from a biopsy of a patient with a vascular disease known as hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT). HHT is a familial disease characterised by small vascular malformations on the skin and mucosal linings and epistaxis. These are the first healthy and disease human iPS cell lines to be generated in the Netherlands and are described here for the first time. Human skin fibroblasts were reprogrammed by retroviral overexpression of the four transcription factors OCT3/4, SOX-2, KLF4 and C-MYC, the most reproducible method described to date. Four weeks after retroviral infection, small, tightly packed colonies emerged, which displayed the typical morphology of human embryonic stem cells, e.g. large nuclei, a small amount of cytoplasm and tight intercellular contacts (figures 1A and B). Similar to hESCs, the iPS cells derived expressed a typical set of human stem cell markers, including OCT3/4, SOX-2, Nanog, SSEA-3, and TRA-1-81, but were negative for mouse ESC marker SSEA-1 as determined by immunostaining (figures 1C to H). The expression of additional stem cell markers at the mRNA level was confirmed by semiquantitative RT-PCR (data not shown). In culture, the iPS cells continuously self-renew and have so far been maintained for more than 30 passages (more than six months) without any obvious phenotypic changes. Additionally, all of these human iPS cell lines display a wide spectrum of differentiated cell phenotypes when appropriately stimulated in culture, including cardiomyocytes and vascular endothelial cells.

Figure 1.

Undifferentiated human iPS cells (A) resemble undifferentiated hESC (B) in morphology. Immunofluorescence analysis of undifferentiated iPS cells for a range of proteins expressed in undifferentiated embryonic stem cell (C-H). Undifferentiated human iPS cells express pluripotency transcription factors OCT3/4, SOX-2 and Nanog (C-E, nuclear localisation) and cell surface markers TRA-1-81 and SSEA-3 (F, G) but are negative for the mouse ESC marker SSEA-1 (H). All cells were co-stained with a nuclear dye (Dapi, blue).

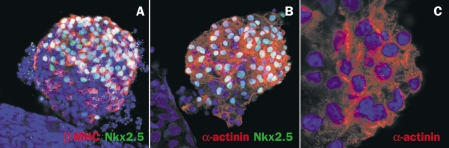

We have developed an efficient co-culture system to differentiate hESC into cardiomyocytes.7,17,18 This method recapitulates signals present in early embryonic development, where the endoderm cell layer provides signals to drive cells in the adjacent mesoderm into the cardiac lineage.19 When seeded on visceral endoderm-like (END-2) cells, hESC form rhythmically contracting areas within seven days following initiation of co-culture. Similarly, contracting areas appeared within a similar time frame when human iPS cells were co-cultured with END-2 cells. The cardiac identity of beating cells derived from the human iPS cells was confirmed by immunostaining with cardiac specific markers α;-actinin, β-myosin heavy chain (MHC) and NKX-2.5 (figures 2A and B). In addition, the cells showed an intracellular striated pattern that is typical for cardiomyocytes (figure 2C). As expected, the HHT human iPS cell lines were also pluripotent and able to form cardiomyocytes (data not shown). Currently, further characterisation of these iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes using patch-clamp electrophysiology and multielectrode arrays (MEA) is ongoing, and responses to drugs that, for example, alter QT interval, are being investigated. Whilst preliminary, the stability of the cells lines including their maintenance of a normal karyotype is encouraging, and demonstrates that the methodology used can be extended to studies of other cardiovascular genotypes of interest, particularly those with an expected electrophysiological phenotype such as long QT or Brugada syndrome.

Figure 2.

Human iPS cells can differentiate into cardiomyocytes in co-culture with END-2 cells. Immunofluorescent staining of contracting areas with antibodies against cardiac structural proteins β-myosin heavy chain (A, red) or α;-actinin (B, C, red) and cardiac transcription factor NKX 2.5 (A, B, green). At higher magnifications, cells stained for α;-actinin show the characteristic striated pattern of cardiomyocytes (C). All cells were co-stained with a nuclear dye (Dapi, blue).

The generation of iPS cell lines from patients with mutations in genes encoding contractile proteins will also be of interest. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is frequently caused by mutations in genes encoding sarcomeric proteins (e.g. β-myosin heavy chain) which often leads to impaired contractile performance.20 Recent publications have shown that contractile properties of cells can be demonstrated in vitro by plating for example cardiomyocytes on flexible substrates where the degree of distortion is proportional to the contractile force.21

The iPS cell lines generated in our laboratory to date were all derived from fibroblasts grown from skin samples. Small biopsies are at the borderline of feasibility because quiescence of skin fibroblasts, precluding retroviral reprogramming, can occur before sufficient numbers have been obtained in culture. Currently we are investigating whether alternative sources of somatic human cells, perhaps more readily available in the clinic, can be used for reprogramming. For example, keratinocytes from hair follicles have been reported to reprogram more efficiently than skin fibroblasts.9 A small volume of blood (∽ 3 ml) may also contain sufficient reprogramming-permissive cells. In addition, experiments to reprogram cells without the use of retroviral vectors are ongoing, including the re-excision of integrated DNA encoding the reprogramming factors after complete reprogramming.

With the development iPS cell technology three years ago, a new era of disease pathology and possibly future therapy is evolving: easily accessible cells from the adult body and cord blood can be converted within a few weeks into an embryonic stem cell-like state, which in turn can differentiate into many cell types of the human body. We have shown here that we are able to convert a cell from a skin sample of an individual to a beating cardiomyocyte from the same individual in a best case, within eight weeks. In instances where a cell from a patient with a genetic mutation is reprogrammed, the resulting iPS cell line and its differentiated derivatives will serve as excellent models for a better understanding of mechanisms underlying the disease. This, together with the ability to test new drugs, will lead to novel therapeutic concepts in the near future. In the long-term, iPS cell derivatives may also serve as a customised source of cells for cell replacement therapies. To achieve these goals in the cardiovascular field, close collaboration between clinicians from the principal hospitals in the Netherlands and basic researchers could support major contributions to the field worldwide.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank A. el Ghalbzouri and S. Commandeur (Dermatology, LUMC) and R. Gortzak (Oral Surgery, LUMC) for providing skin fibroblasts and oral mucosa samples respectively and F. Disch and CJJ Westermann (St Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein) for tissue from HHT2 patients. We also thank D. de Jong, K. Szuhai and H. Tanke (Molecular Cell Biology, LUMC) for karyotyping analysis. H. Mikkers (Molecular Cell Biology, LUMC), R. Nauw, S. Braam, R. Passier (Anatomy & Embryology, LUMC) and C. Dambrot, D. Atsma (Cardiology, LUMC) are thanked for input in cell staining, differentiation protocols, cell culture support and discussion. This work was supported by the Netherlands Proteomics Initiative (CF) and the Netherlands Heart Foundation (grant number 2008B106; CLM) and EU FP7 (‘InduStem’ PIAP-GA-2008-230675) (RD).

References

- 1.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors. Cell. 2007;131:861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;316:1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, et al. Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2008;134:877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamanaka S. A Fresh Look at iPS Cells. Cell. 2009;137:13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freund C, Mummery CL. Prospects for pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in cardiac cell therapy and as disease models. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107:592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Passier R, Ward-van Oostwaard D, Snapper J, et al. Increased cardiomyocyte differentiation from human embryonic stem cells in serum-free cultures. Stem Cells. 2005;23:772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruan Y, Nian Liu N, Priori SG. Sodium channel mutations and arrhythmias. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aasen T, Raya A, Barrero MJ, et al. Efficient and rapid generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human keratinocytes. Nature Biotech. 2008;26:1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loh YH, Agarwal S, Park IH, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human blood. Blood. 2009;113:5476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JB, Sebastiano V, Wu G, et al. Oct4-Induced Pluripotency in Adult Neural Stem Cells. Cell. 2009;136:411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi Y, Desponts C, Tae Doe J, et al. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts by Oct4 and Klf4 with Small-Molecule Compounds. Cell Stem Cell 2008;3:568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okita K, Nakagawa M, Hyenjong H, et al. Generation of Mouse Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Without Viral Vectors. Science. 2008;322:949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stadtfeld M, Nagaya M, Utikal J, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated without viral integration. Science. 2008;322:945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebert AD, Yu J, Rose Jr FF, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells from a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Nature. 2009;457:277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Laake LW, Passier R, Monshouwer-Kloots J, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes survive and mature in the mouse heart and transiently improve function after myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Res. 2007;1:9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freund C, Ward-van Oostwaard D, Monshouwer-Kloots J,et al. Insulin Redirects Differentiation from Cardiogenic Mesoderm and Endoderm to Neuroectoderm in Differentiating Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Stem Cells. 2007;26:724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mummery C, Ward-van Oostwaard D, Doevendans P, et al. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to cardiomyocytes: role of coculture with visceral endoderm-like cells. Circulation. 2003:107:2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nascone N, Mercola M. An inductive role for the endoderm in Xenopus cardiogenesis. Development. 1995;121:51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soor GS, Luk A, Ahn E, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: current understanding and treatment objectives. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feinberg AW, Feigel A, Shevkoplyas SS, et al. Muscular thin films for building actuators and powering devices. Science. 2007;317:1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]