Abstract

It is probable that nearly every natural product structure results from interactions between organisms. Symbiosis, a subset of inter-organism interactions involving closely associated partners, has recently provided new and interesting experimental systems for the study of these interactions. This review discusses new observations about natural product function and structural evolution that emerge from the study of symbiotic systems. In particular, these advances directly address long-standing “how” and “why” questions about natural products, providing fundamental insights about the evolution, origin, and purpose of natural products that are inaccessible by other methods.

Introduction

Natural products — for simplicity here defined as products of secondary metabolism — have long been central to drug discovery and organic chemistry. Discrete organisms such as plants, marine animals, and cultivated microbes have provided much of the chemical diversity inspiring syntheses and filling the pharmaceutical pipeline.1 Key questions intriguing many natural products chemists and biologists have been: What are the natural roles of these compounds (why do they exist)? How does the vast structural diversity behind these products originate and evolve? New methodologies now enable these questions to be addressed directly in the environment, where natural products are playing their roles and where selection pressure is operating.2

The environment important to these natural products is found at the level of inter-organism interactions. This review focuses on recent advances on symbiotic interactions between microbes and other organisms, especially animals. There are many other types inter-organism interactions, such as intra-species pheromones and quorum sensing, predator-prey molecules, and so on, which are outside the scope of this review. Within symbiotic associations, there is selection over a long period of time leading to new and interesting chemicals and biochemical reactions. These interactions are also tightly defined — a specific type of animal will be always or usually associated with a certain symbiotic microbe — and therefore they are more tractable than other types of less controlled situations. For simplicity, one could think of this as chemical biology operating at a planet-wide scale, where the problem is centered in biological macromolecules that keep changing, and the evolutionary solution is found in small natural products that target these molecules.

Technical advances that make it possible to study environmental systems such as symbiosis in detail include a greater sensitivity in chemical analysis, vast improvements in chemical visualization techniques, metagenomic methodologies, advances in cultivation techniques, and powerful and affordable DNA sequencing technologies.2 Previously, with a few exceptions, it was necessary to study these systems by physically manipulating tissues, for example in order to localize small molecules within specific tissue types or to prepare samples for microscopy.3 Alternatively, cells or tissues could be brought into culture, although this was extremely challenging with limited success and is greatly facilitated by modern techniques. Both of these experimental approaches, while greatly advancing the science and having certain advantages, also suffered from obvious limitations. The newer methods have allowed the direct interrogation of environmental systems such as symbioses in situ. This review discusses a few of the advances that have been made and some possible future directions enabled by these technologies. Finally, it should be noted that animals and plants also produce natural products, and that there are many other fields of natural products not described in this review, which focuses on symbiosis.

Symbiosis: a defined molecular exchange

Symbiosis at its simplest level is the stable interaction of organisms.4 This definition excludes organisms that interact casually or that live next to each other in the environment, but it makes no judgment as to whether or not an association is mutually beneficial. Among the clearest examples of symbiosis are bacteria that exchange small molecule nutrients or natural products with their “host” organisms. Because this small-molecule exchange is demonstrably important to the symbiosis over time, it provides an anchor for experimental approaches that address the bigger questions of evolution and purpose.

As symbioses based upon small molecules evolve, genes that are not important to the interaction often become lost, while small-molecule metabolic genes seem to be maintained. Extreme examples of this effect are mitochondria and chloroplasts, which are thought to arise from bacteria but which are now embedded within the genetic context of their host cells.5 At the other end of the spectrum, some photosynthetic bacteria live within host animals and contribute to fitness, but they are not required for growth.6 Intermediate between these extremes are some bacteria living within insects.7, 8 These bacteria are important for their synthesis of amino acids and vitamins, and many other genes have degraded, but they retain some degree of independence and are not organelles. In at least one of these cases, bacterial symbiont genes were horizontally transferred to and are actually expressed by host animal cells, indicating a tight genetic and metabolic coupling between these symbiotic organisms.8

Small molecule exchange in the form of nutritional molecules leads to tight integration and co-evolution of symbiotic organisms (Fig 1). It is becoming increasingly apparent that other types of small molecules, such as natural products, also perform very precise and defined roles in symbiotic associations.3, 9, 10 Natural products are often structurally complex and target specific biological macromolecules. The potential roles of these natural products from symbiotic microbes are extremely varied. For example, bacteria secrete quorum-sensing molecules important in the colonization of host animals.11 Some bacteria secrete small molecules that deter predation on whole animals,12, 13 while other small molecules affect the species and strain composition of symbiotic bacteria within animal hosts.14 There are many potential evolutionary paths to the observed natural product structural diversity, reflecting the diverse roles of natural products from symbiotic associations.

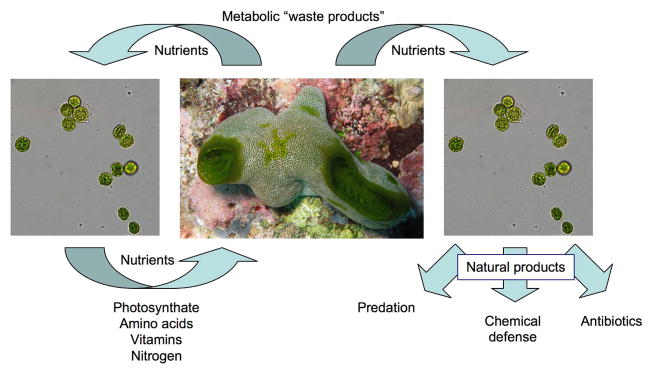

Figure 1.

Roles of metabolism in symbiosis. Macroorganisms such as this ascidian animal (center) share metabolic products with symbiotic microbes such as Prochloron bacteria (left and right). In return, bacteria can provide metabolic intermediates back to hosts (left) or they can synthesize natural products that have many different possible roles, including aiding in predation, chemical defense, or antibiosis. Many other roles are possible, and no roles for natural products have yet been experimentally determined for the symbiosis shown. Ascidian photo: Chris Ireland. Prochloron photo: Mohamed Donia.

The interaction of Prochloron bacteria with host ascidian animals in tropical oceans provides an excellent example of exchange of nutrients between animals and bacteria — a symbiosis based upon small molecules.15 There is a plethora of papers describing the sharing of photosynthate fixed by Prochloron with the host animal, and in some cases nearly all required carbon comes from the bacteria.16–22 In return, the host has been demonstrated in many cases to provide waste nitrogen and other metabolic by-products that allow Prochloron to be highly productive in a relatively nitrogen-poor environment. Prochloron also recycles this nitrogen, providing back to host usable nitrogen from waste sources.23 Prochloron-containing ascidians often contain extremely diverse natural products, such as the patellamides and relatives,24, 25 which are found throughout the ascidian and cyanobacterial tissues.26 Recently, it was shown that Prochloron produce these compounds,27, 28 leading to yet another small molecule exchange within the symbiotic interaction. While this is an illustrative example, it is only one of the many that have been described.

Clearly, in symbiotic associations, organisms cooperate in the synthesis of natural products. As in the example above and others, associated organisms exchange small molecules that may become building blocks for the resulting natural products. Alternatively, partners may modify the natural products produced by each other. Because selection of microbial compounds is taking place within the context of a host organism such as an animal or plant, from one perspective it may be this cooperation in evolution that likely leads to much natural product diversity.

Roles of natural products

Symbiosis is providing increasing evidence for the roles of natural products in their native environments. Key examples are found in bacteria living symbiotically with animals from diverse taxonomic groups, including nematodes, sponges, ascidians, bryozoans, insects, and others.

Phylum Nematoda may be a major contributor to bacterial natural product diversity. It has been estimated that nematodes are the most abundant animals on earth.29 Since many nematodes prey on bacteria,30 it follows that bacteria in soil stand a good chance of passing through a nematode during their lives, leading to diverse symbiotic and non-specific interactions. Large numbers of natural products may thus be attuned to interact with biochemical targets in nematodes, which are an incredibly genetically diverse group with many protein targets.31

Nematodes: sampling “terrestrial” bacteria

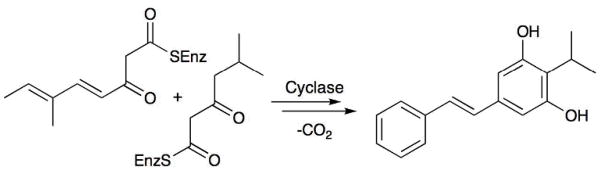

A good example of symbiotic interactions between nematodes and bacteria is the well-studied relationship between nematodes Heterorhabditis spp. and the gamma-proteobacterium, Photorhabdus luminescens.32 The nematodes prey upon insects and contain P. luminescens in specialized structures. When they invade insects, the nematodes release P. luminescens, which grows rapidly and kills the insects within 72 hours. Nematodes feast on the resulting bacteria and carry them as symbionts when they leave the gutted insects. P. luminescens is known to produce stilbene derivatives that are essential to this interaction, where they presumably function as antibiotics and in suppressing the insect immune system (Fig 2).33–35 Recently, it was shown that the stilbenes also function as signals to the nematodes.35 In the absence of these signals, post-infective juveniles do not advance to the next stage in their life cycle. Genes for the biosynthesis of the stilbenes were cloned, leading to identification of a novel stilbene biosynthetic pathway that is more similar to fungal coumarin synthesis than to the prototypical plant routes. As the known inventory of bacterial nematode symbionts is massive, it is likely that many more natural product-based interactions will be uncovered in future years.

Figure 2.

Biosynthesis of a stilbene by a nematode symbiont.

A close relationship in a marine animal

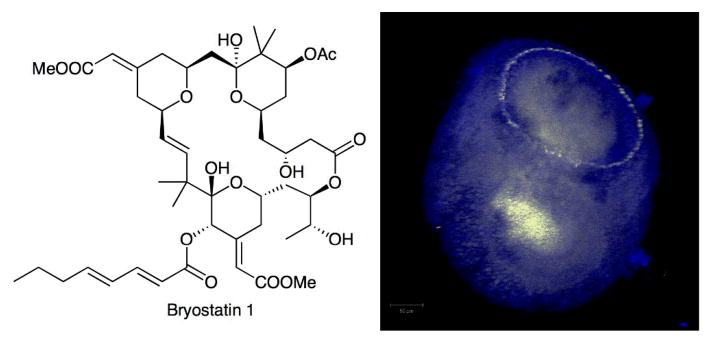

The nematode story illustrates a tightly integrated metabolic exchange allowing the host animals to exploit a new environment through predation. Work with the bryozoan Bugula neritina and its bacterial symbiont, ‘Candidatus Endobugula sertula’, has shed light on another type of allelochemical interaction: defense from predation. B. neritina is well known because it contains the extremely potent protein kinase C inhibitors, bryostatins, which are anticancer candidates.36, 37 The animal was known to harbor specific bacteria in the pallial sinus of its larvae.38 Molecular biological investigation led to the identification of these bacterial symbionts as the gamma-proteobacterium, ‘E. sertula’.39 Feeding studies indicated that bryostatins are polyketides,40 and polyketide synthase (PKS) genes were rapidly identified from metagenomic samples containing ‘E. sertula’, representing the first such metagenomic approach to biosynthesis in marine animals (Fig 3).41 The entire putative bryostatin biosynthetic gene cluster has been sequenced and carefully analyzed.42, 43 The maintenance of this relatively large gene cluster could reflects the importance of bryostatin to the symbiosis. By analogy, in other obligate symbioses such as those involving Buchnera spp. or Wolbachia spp., nutritional exchange is likely important, and certain types of nutritional genes have resisted genome degradation.7 Complicating this issue is the fact that Bugula and ‘E. sertula’ have not co-speciated.44

Figure 3.

Bryostatins and ‘E. sertula’ are found throughout the tissues of the host animal, B. neritina. The structure of bryostatin is shown, as well as a series of confocal images of B. neritina larvae. The location of bryostatins is indicated in blue, while ‘E. sertula’ is labeled with a fluorescent yellow probe. (Photo kindly provided by Koty Sharp.)

Bryozoans are sedentary filter feeders that live most of their lives solidly attached to a substrate.30 However, like many other sedentary marine animals, they release larvae for dispersal in the open ocean. At this stage, the larvae are highly vulnerable to predation. It has been shown experimentally that bryostatins make B. neritina larvae unpalatable to predators, making it extremely likely that bryostatins play a role in the chemical defense of these young animals.12 In combination with genetic evidence, this makes it one of the strongest stories in the natural product literature, coming among the closest to providing an answer to the “why” question of natural product and symbiotic evolution. More data is required to firmly answer this question, but the described studies have at least made this a tractable problem.

Further evidence has come from recent confocal microscopy studies using whole B. neritina animals in different phases of their life cycles.45 In this work, bryostatins were labeled with protein kinase C and anti-PKC antibodies. Simultaneously, ‘E. sertula’ was labeled with a targeted oligonucleotide probe. In a few key stages of the life cycle when bryostatins are being actively synthesized, bryostatins appeared in a halo surrounding the ‘E. sertula’ cells. Additionally, ‘E. sertula’ could be followed through the life cycle of the host, and very clearly some mechanism exists to package the bacteria into the larvae prior to dispersal in the open ocean. Thus, bryostatins are natural products from bacterial symbionts that are tightly coupled with chemical defense of animals.

Insects use bacteria for chemical defense

Insects comprise one of the most abundant and diverse animal phlya on earth,30 and it is no surprise that a large number of symbiotic interactions have been investigated. A few recent examples are available illustrating roles for natural products.

Paederus spp. beetles are a widely distributed species that contain a fluid that causes painful blisters in humans, an effect that is clearly related to chemical defense.13, 46 The toxic principle has been identified as pederin, which is closely related to polyketides from sponges, including onnamide. Uncultivated symbiotic bacteria living within Paederus fuscipes were shown to be associated with toxin production.47 Using a metagenomic approach, it was demonstrated that the bacteria contain a biosynthetic gene cluster encoding pederin.48 Biochemical proof of function was not obtained, but the gene order and sequence was very compelling.

Another rich system involves ants, which are among the most diverse and abundant groups on earth. Ants have been extensively examined for their symbiotic interactions with bacteria, again largely on a nutritional basis. A very clear example of the role of natural products in ants can be found in the leaf cutters, which cultivate filamentous fungi as their primary (or sole) food source.49, 50 The fungi are often vertically transmitted and thus co-evolve with their ant hosts.49, 51, 52 Unfortunately, they are quite vulnerable to infection by other organisms such as fungi and bacteria, which could potentially destroy this ancient symbiosis. It was noticed that these ants were commonly coated with a waxy-looking mass, which turned out to be actinomycete bacteria, such as Pseudonocardia.53–57 The bacteria secrete small molecule natural products that defend the fungi from attack. In this case, ants use microbial natural products to control the composition of other symbiotic microorganisms.

Even humans harbor symbiont-derived natural products

Ants are similar to humans and related mammals in that we also contain bacterial natural products that control the composition of microbial symbionts. Bacterial isolates from human and higher animal intestines often produce bacteriocin ribosomal peptides, including microcins and lantibiotics.58 These metabolites are also common constituents in many environments, including ascidian symbionts in the ocean.59–61

Much of the bacteriocin literature includes statements that these molecules are synthesized to antagonize bacterial strains that are very closely related to the producing organism. For example, E. coli producing a bacteriocin may be lethal to nearly identical strains that lack this bacteriocin pathway.62, 63 It is thought that these types of interactions carve out niches for multiple, nearly identical strains, keeping individual strains from dominating a community.64, 65 However, increasingly there are reports of very non-selective bacteriocins that are broadly antibiotic or that target other organisms.66

With this complex background of multiple types of biological activity, it comes as no surprise that human and other mammalian intestines harbor a diverse number of different bacteriocin pathways.67 How these interact within the intestine is still an open question. Many studies address lethality of compounds against pathogenic strains. For example, enteric bacteria encode bacteriocins that inhibit E. coli 0157:H7, a potentially deadly pathogenic strain that can induce hemolytic uremic syndrome, especially in children.14 It was shown that 0157-targeting bacteriocins become more abundant with aging, which may at least in part explain why children are more vulnerable to the strain. Other studies demonstrate that interactions between bacteriocins are likely to affect the bacterial composition of the human intestine, using ecological models or purified bacterial strains.63

In addition, data are limited regarding potential non-bacteriocin antibiotics from intestinal flora. For example, there is probably an enterobactin-like siderophore that is partially responsible for controlling the human iron pool…68 could this molecule be synthesized by intestinal symbiotic bacteria?

The above are a few examples of how the study of symbiosis has led to new insights into natural product roles in chemical defense, predation, and microbial population control.

Genetic origins of natural products

In some cases, symbiotically produced natural products are characterized at the molecular genetic level, providing insight into biosynthetic pathway evolution in closely related strains of bacteria. In other cases, insights about gene transfer and convergent evolution are obtained by observing symbiosis.

Trans-acyltransferases in symbiosis

A special case is found in natural products from symbionts made by the trans-acyltransferase polyketide synthase (PKS) proteins.69 This subclass of PKS is often specifically found in symbiotic bacteria for as yet unknown reasons, and they provide fascinating insights into the molecular mechanisms of pathway evolution. Bryostatins, from bryozoan symbionts, and pederin, from insect symbionts, were described above and are good examples of compounds made by this enzyme class. The molecules are similar in that they are potently cytotoxic, leading to presumed or determined roles as chemical defensive agents. In addition, they are synthesized by similar types of biosynthetic proteins. Gene clusters for these molecules have been at least partially sequenced, revealing that the core carbon skeletons are synthesized by “trans-acyltransferase” PKS proteins.69 In addition, pederin contain genes for nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) proteins, which synthesize peptide and ester bonds using amino- or hydroxy-acids.

Bryostatin PKS proteins are encoded as several individual genes.43 The resulting proteins are modular, in that each extension of acetate in the final product is catalyzed by a different protein module. Within the PKS genes, there are several regions that are perfect copies of each other. These repeated regions have a consequence in the final structure, and due to the lack of mutations may be relatively recent in origin. Alternatively, there may be other processes involved, such as equilibration by gene conversion. The duplicated regions were proposed to be important in the natural proposed “shuffling” involved in modular PKS and NRPS proteins.

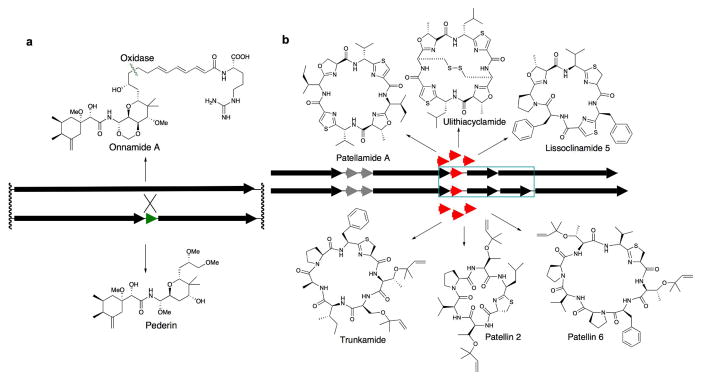

Pederin was the first natural product from a symbiont for which a large biosynthetic gene cluster was sequenced.48 The cluster consisted primarily of trans-acyltransferase PKS and NRPS genes. Intriguingly, too many polyketide and peptide modules were present in this gene cluster. Bioinformatic analysis indicated that the cluster should lead to a compound more similar to the larger molecule, onnamide, which was originally isolated from sponges (Fig 4). However, one of the PKS genes was interrupted by a sequence encoding an oxidase domain, probably leading to a smaller polyketide product – pederin.

Figure 4.

Evolution of natural product pathways. (a) Pederin and onnamide. Putative PKS in black, interrupting oxidase in green. The pederin cluster contains an interrupting oxidase, without which it would produce an onnamide-like structure. (b) Ascidian compounds, patellamides and relatives. Putative enzymes in black, precursor peptides in red. Variants of the patellamide pathway (top) are virtually 100% identical except in small segments that directly encode the resulting patellamide products. The same pattern is seen in variants of the trunkamide pathway (bottom). These pathways are >97% identical at the DNA level except in a small region marked by a blue box. Differences in heterocyclization versus prenylation of serine and threonine can be explained by the sequence difference within this blue box.

The later putative onnamide gene cluster, isolated from sponges, was very similar to the pederin cluster, despite the large distance in habitat and location: the pederin samples were obtained from terrestrial beetles in Turkey, while the sponge was harvested in temperate waters near Tokyo, Japan.70 Despite this geographic and taxonomic separation, the interrupting oxidase provided a clear example of molecular evolution to create new compounds in symbiosis.

Fungi and plants: convergence or lateral transfer?

Another example of pathway evolution is afforded by plant symbiotic fungi. Gibberellins are plant hormones that are synthesized both by plants and by symbiotic filamentous fungi.71 Almost incredibly, the pathways to gibberellin biosynthesis are convergent in these two organisms and do not result from horizontal transfer. Recent data indicate that this hormone example may be just one of many. Podophyllotoxin72 and camptothecins73 are plant toxins that are synthesized by filamentous fungi. Finally, paclitaxel biosynthesis by fungi remains controversial. The compound is clearly synthesized by yew tree proteins, since plant biosynthetic genes for most steps have been cloned.74, 75 However, there are several reports from different labs concerning the identification of paclitaxel in the extracts of yew-derived fungi.76–80 It would be interesting to know whether these cases result from lateral gene transfer or if, as in the case of gibberellins, there is some other evolutionary mechanism.

There are now many examples of convergence in natural products, including fungal and actinomycete polyketides,81 morphine in plants and humans,82 and the stilbene-nematode system cited above,35 among other examples. Thus, convergent evolution is not a new observation, nor is it special to symbiosis. What is new and special in symbiosis is that organisms convergently make the same compound in the same location, possibly for the same or nearly the same purpose, at least in one case. The underlying biology is likely to be extremely revealing about the evolution and role of natural product pathways and is worthy of investigation.

Mining symbiotic metagenomics reveals single mutations to new compounds

One of the advantages of marine animals in studying pathway evolution is that they often contain many similar natural products that comprise families of related structures. Not all marine animal products are part of families, but when they are the families can be quite large. For example, at least 60 patellamide variants have been detected in ascidians.83 If these metabolites were made by symbiotic bacteria, it should be possible to detect individual mutations leading to diverse new structures. The major advantages of symbionts over cultivated bacteria are as follows: 1) cultivated bacteria are randomly obtained from different environments and are therefore randomly related to each other, while symbiotic bacteria are found in defined environments and could be related to each other in a defined way; 2) cultivated bacteria are found by chance, while it is easy to recognize a symbiont associated with a macroorganism; 3) symbiotic bacteria are often very closely related to each other in comparison to randomly cultivated organisms; 4) the chemistry of these organisms can be readily determined by immediately extracting a whole animal or plant, whereas cultivated microbes need to be cultivated under the correct conditions and extracted often much later. Therefore, one can easily find related symbiotic bacteria and correlate the genetic relationships to chemistry of whole animals rapidly. Of course, the disadvantage of working with symbiotic bacteria is that it is still very difficult to clone the first of a pathway type from environmental samples. In addition, although the chemistry of an association can be readily determined, it is still technically demanding to determine the biogenetic source of a molecule. However, once the initial discoveries are made, it takes days to clone and study hundreds of variants.

Careful consideration of the above led to the idea that examination of closely related symbionts would be informative for biosynthetic engineering.84 It was predicted that closely related producing strains of symbiotic bacteria would contain nearly identical biosynthetic genes. Only the regions of importance for chemical differences would be reflected in the biosynthetic sequences. By contrast, relatively large differences are seen even between very closely related pathways from cultivated bacteria, making the evolutionary and engineering analysis challenging.

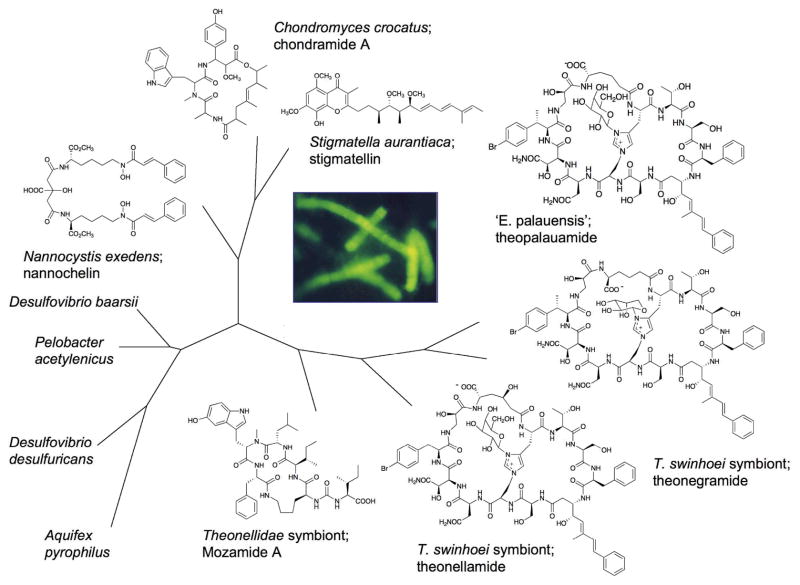

This idea gained some traction in work with the sponge Theonella swinhoei. It was shown that filamentous bacteria within this sponge contained complex polyketide-nonribosomal peptides, exemplified by theopalauamide (Fig 5).84, 85 16S rRNA gene analysis was performed using a number of sponges containing slight variants of theopalauamide. 16S rRNA gene variation was correlated with structural variation: as small molecules varied, so did the underlying taxonomy of the presumably producing strains of bacteria. This supported the possibility that small genetic changes would correlate with small structural differences. More recently, these filamentous bacteria have been found in other sponges with important, diverse natural products as well.86–88

Figure 5.

Potential co-evolution of sponge symbionts and natural products. A 16S rRNA tree was derived for the sponge-specific filamentous bacterial group, ‘Candidatus Entotheonella palauensis’. The symbionts are delta-proteobacteria the branch closely with the myxobacteria (upper left) and sulfate reducers (lower left). ‘E. palauensis’ sequences were obtained from individual sponges and compared with natural products isolated from those same sponges. Filamentous ‘E. palauensis’ hybridized to a specific fluorescent probe are shown at center. Adapted from a figure first printed in Marine Biology, reprinted with permission.

Further work with ascidians has firmly validated this approach. Certain ascidians contain a large family of related cyclic peptides, exemplified by patellamide A and trunkamide.25, 89 These peptides are N-C terminally cyclized and further modified to heterocycles derived from Cys, Ser, and Thr (Fig 4). In some cases, Ser and Thr are prenylated, presumably by dimethylallylpyrophosphate. The 60 known structures comprise an overlapping family of compounds with different amino acid substitutions, variable numbers of amino acids, and different modifications. The question was, evolutionarily, how to go from one compound to another.

Patellamides and relatives are found in ascidians that harbor cyanobacterial symbionts, Prochloron spp., that have eluded cultivation.15 It had long been proposed that these bacteria synthesize patellamides and relatives,25 although contradictory evidence had been obtained by cell separation studies.26, 90 Two different approaches were taken to successfully identify patellamide biosynthetic genes in Prochloron. Genome sequencing led to identification of biosynthetic genes for the patellamides in one study,27 while in another direct DNA cloning and chemical detection of the resulting Escherichia coli library led to identification of patellamide-encoding plasmids.91

From metagenomic analysis of Prochloron spp., the patellamide pathway was cloned and sequenced, leading to identification of four required proteins and a small precursor peptide.27 This peptide, PatE, directly encoded two patellamide products on a ribosomally translated peptide. The remaining proteins are essential to modify the precursor into the small molecule products, which represent the phenotype of this pathway.

In a survey of 40 Prochloron-containing ascidians, 28 new PatE variants were discovered.28 These variants were very different in comparison to PatE only in the exact region encoding products. Strikingly, all of these peptides existed within an invariant genetic background, with essentially no mutations in protein or intergenic regions. Even PatE homologs were ~100% conserved in regions not directly encoding patellamide products. Thus, a “square function” of evolution leads to changes in chemical structure: only a tiny region of an 11 kbp gene cluster was extremely variable, leading to a natural combinatorial library. This phenomenon was not previously observed in any other system.

More recently, a related pathway leading to the prenylated compound group exemplified by trunkamide was discovered.83 This pathway was very similar to the patellamide pathway except in a central region of the cluster. In this region, between 25–70% gene sequence identity was found, much lower than in the other pathway genes. By expression in E. coli, it was shown that these gene differences led to prenylation of serine and threonine, rather than heterocyclization as in the patellamide cluster. The predicted prenylating protein is not related to known prenyltransferases and thus would be recalcitrant to bioinformatics approaches. By directly examining genetic changes within defined symbioses, the limitations of bioinformatics could be bypassed, leading directly to functional information about new proteins.

These examples illustrate evolutionary pathways that are different than those discerned in cultivated microbes so far. Precise changes are seemingly more easily identified in these symbionts, although it could be argued that data are currently very limited. The origin of chemical diversity, through gene shuffling, gene interruption, and introduction of hypervariable regions, can be clearly and directly observed. When tied to a natural product role, these evolutionary stories will be highly informative concerning the impact of selective pressure on chemical diversity.

Biodiversity driving future directions

It is clear that we are getting close to answering some of the fundamental questions in the field of natural products research. A primary question has to do with the role of these natural products. It has traditionally been very difficult to demonstrate roles of these compounds: even if they behave as toxins or deter predation, is that their “purpose”? The genetic tools that result from symbiosis studies make hypotheses about the roles rigorously testable.

It is critical to determine whether natural product pathways are associated with single or multiple strains within complex symbiotic interactions. There is growing evidence that human gut microbes contain a mobile pool of DNA that encodes proteins necessary for human nutrition.92, 93 The mobile DNA would move between strains and species of bacteria, bringing with it encoded functions important to survival in the specific environment. In this scenario, the bugs don’t matter as much as the functions that they encode. The same phenomenon has been identified in the marine environment, where metagenomic studies have led to the idea that the environment itself selects for types of functional genes more than for taxa of individual bacteria.94, 95

Many presumably symbiont-produced natural products are potently toxic against eukaryotic proteins, and therefore resistance to these agents must be evolved in the host eukaryote. Also, within marine invertebrate symbioses, it seems highly likely that lateral transfer of pathways occurs. As one of many examples, swinholide derivatives were isolated from cyanobacteria,96 but they have also been attributed to unicellular heterotrophic bacteria within whole sponge animals.97 If, in some symbiotic associations, the mobile pool of DNA encoded certain natural products, this would provide evidence for the importance of the compounds to the overall health of the association. Bacteriocins from human commensals are known to be sometimes encoded on plasmids or even in phages, supporting this mobile pool.98, 99 Alternatively, individual natural products may be associated only with certain strains, and the interaction between hosts and individual strains becomes more important. This latter case is clearly key to the bryozoan-bryostatin system, where related symbionts produce related molecules across across a range of bryozoans, and the interaction appears to be controlled at the strain level.

The patellamide group in ascidians provide an example in which pathway evolution may help to understand the roles of the compounds in nature. It has been shown that the enzymes can process even unnatural sequences that are much different than those encoding natural compounds, yet only certain sequence subtypes appear to be abundant in nature. Mutations are highly focused to a 48-nucleotide region out of an 11 kilobase pair cluster, leading to this observed phenomenon.28 Clearly, the resulting natural products are the focus of selective pressure. There are many other examples in which families of natural products are known from related sources. The question remains as to what type(s) of molecular processes drive these genetic changes.

Cooperation between organisms has led to an enormous diversity of natural products that are specifically targeted to biomacromolecule, with functional consequences. The interplay between closely associated organisms has given rise to directly observable, single evolutionary changes and have allowed a clearer understanding of natural product roles, impacting our understanding of biodiversity. There are many more examples of known natural products produced by symbionts, providing a wealth of subjects for future work.

Acknowledgments

Our work on symbiosis is funded by NIH GM071425 and by NSF EF-0412226 (subcontract from University of Maryland). The author thanks M.G. Haygood (OHSU) for critically reading an early version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simmons TL, et al. Biosynthetic origin of natural products isolated from marine microorganism-invertebrate assemblages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4587–4594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709851105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haygood MG, Schmidt EW, Davidson SK, Faulkner DJ. Microbial symbionts of marine invertebrates: Opportunities for microbial biotechnology. J Molec Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;1:33–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith DC. Symbiosis research at the end of the millenium. Hydrobiologia. 2001;461:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Margulis L. The Origin of Eukaryotic Cells. Yale University Press; New Haven: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wahl M, Mark O. The predominantly facultative nature of epibiosis: experimental and observational evidence. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1999;187:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shigenobu S, Watanabe H, Hattori M, Sakaki Y, Ishikawa H. Genome sequence of the endocellular bacterial symbiont of aphids Buchnera sp. APS. Nature. 2000;407:81–86. doi: 10.1038/35024074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hotopp JC, et al. Widespread lateral gene transfer from intracellular bacteria to multicellular eukaryotes. Science. 2007;317:1753–1756. doi: 10.1126/science.1142490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piel J. Metabolites from symbiotic bacteria. Nat Prod Rep. 2004;21:519–38. doi: 10.1039/b310175b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt EW. From chemical structure to environmental biosynthetic pathways: navigating marine invertebrate-bacteria associations. Trends Biotechnol. 2005;23:437–440. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visick KL, Foster J, Doino J, McFall-Ngai M, Ruby EG. Vibrio fischeri lux genes play an important role in colonization and development of the host light organ. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4578–4586. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.16.4578-4586.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopanik N, Lindquist N, Targett N. Potent cytotoxins produced by a microbial symbiont protect host larvae from predation. Oecologia. 2004;139:131–139. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1487-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kellner RLL, Dettner K. Differential efficacy of toxic pederin in deterring potential arthropod predators of Paederus (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae) offspring. Oecologia. 1996;107:293–300. doi: 10.1007/BF00328445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toshima H, et al. Prevalence of enteric bacteria that inhibit growth of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 in humans. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135:110–117. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806006510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewin RA, Cheng L, editors. Prochloron: A Microbial Enigma. Chapman and Hall; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher CR, Trench RK. In vitro carbon fixation by Prochloron sp. isolated from Diplosoma virens. Biol Bull. 1980;159:636–648. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kremer BP, Pardy R, Lewin RA. Carbon fixation and photosynthates of Prochloron, a green alga symbiotic with an ascidian, Lissoclinum patella. Phycologia. 1982;21:258–263. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffiths DJ, Thinh LV. Transfer of photosynthetically fixed carbon between the prokaryotic green alga Prochloron and its ascidian host. Aust J Mar Freshwater Res. 1983;34:431–440. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alberte RS, Cheng L, Lewin RA. Characteristics of Prochloron ascidian symbioses. 2 Photosynthesis-irradiance relationships and carbon balance of associations from Palau, Micronesia. Symbiosis. 1987;4:147–170. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dionisiosese ML, Shimada A, Maruyama T, Miyachi S. Carbonic-anhydrase activity of Prochloron sp. isolated from an ascidian host. Arch Microbiol. 1993;159:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koike I, Yamamuro M, Pollard PC. Carbon and nitrogen budgets of 2 ascidians and their symbiont, Prochloron, in a yropical seagrass meadow. Aust J Mar Freshwater Res. 1993;44:173–182. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koike I, Suzuki T. Nutritional diversity of symbiotic ascidians in a Fijian seagrass meadow. Ecol Res. 1996;11:381–386. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Odintsov VS. Nitrogen fixation in Prochloron (Prochlorophyta)-ascidian associations — is Prochloron responsible. Endocytobiosis Cell Res. 1991;7:253–258. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ireland CM, Scheuer PJ. Ulicyclamide and ulithiacyclamide, 2 new small peptides from a marine tunicate. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:5688–5691. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ireland CM, Durso AR, Newman RA, Hacker MP. Anti-neoplastic cyclic peptides from the marine tunicate Lissoclinum patella. J Org Chem. 1982;47:1807–1811. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Degnan BM, et al. New cyclic peptides with cytotoxic activity from the ascidian Lissoclinum patella. J Med Chem. 1989;32:1349–1354. doi: 10.1021/jm00126a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt EW, et al. Patellamide A and C biosynthesis by a microcin-like pathway in Prochloron didemni, the cyanobacterial symbiont of Lissoclinum patella. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7315–7320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501424102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donia M, et al. Natural combinatorial peptide libraries in cyanobacterial symbionts of marine ascidians. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:729–735. doi: 10.1038/nchembio829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams BJ, et al. Biodiversity and systematics of nematode-bacterium entomopathogens. Biol Cont. 2006;37:32–49. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brusca RC, Brusca GJ, Haver NJ. Invertebrates. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, Massachusetts: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coghlan A. Nematode genome evolution. WormBook. 2005:1–15. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.15.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goodrich-Blair H, Clarke DJ. Mutualism and pathogenesis in Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus: two roads to the same destination. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:260–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paul VJ, Frautschy S, Fenical W, Nealson KH. Antibiotics in microbial ecology. J Chem Ecol. 1981;7:589–597. doi: 10.1007/BF00987707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson WH, Schmidt TM, Nealson KH. Identification of an anthraquinone pigment and a hydroxystilbene antibiotic from Xenorhabdus luminescens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1602–1605. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.6.1602-1605.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joyce SA, et al. Bacterial biosynthesis of a multipotent stilbene. Angew Chem Intl Ed. 2008;47:1942–1945. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pettit GR, et al. Isolation and structure of bryostatin 1. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:6846–6848. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kortmansky J, Schwartz GK. Bryostatin-1: a novel PKC inhibitor in clinical development. Cancer Invest. 2003;21:924–936. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120025095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woollacott RM. Association of bacteria with bryozoans larvae. Mar Biol (New York) 1981;65:155–158. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haygood MG, Davidson SK. Small-subunit rRNA genes and in situ hybridization with oligonucleotides specific for the bacterial symbionts in the larvae of the bryozoan Bugula neritina and proposal of “Candidatus endobugula sertula”. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4612–4616. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4612-4616.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kerr RG, Lawry J, Gush KA. In vitro biosynthetic studies of the bryostatins, anti-cancer agents from the marine bryozoan Bugula neritina. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:8305–8308. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davidson SK, Allen SW, Lim GE, Anderson CM, Haygood MG. Evidence for the biosynthesis of bryostatins by the bacterial symbiont “Candidatus Endobugula sertula” of the bryozoan Bugula neritina. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:4531–4537. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.10.4531-4537.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hildebrand M, et al. bryA: an unusual modular polyketide synthase gene from the uncultivated bacterial symbiont of the marine bryozoanBugula neritina. Chem Biol. 2004;11:1543–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sudek S, et al. Identification of the putative bryostatin polyketide synthase gene cluster from “Candidatus Endobugula sertula”, the uncultivated microbial symbiont of the marine bryozoan Bugula neritina. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:67–74. doi: 10.1021/np060361d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lim GE, Regali LA, Haygood M. Evolutionary relationships of Endoubugula bacterial symbionts and their Bugula bryozoan hosts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008 doi: 10.1128/AEM.02798-07. epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharp KH, Davidson SK, Haygood MG. Localization of ‘Candidatus Endobugula sertula’ and the bryostatins throughout the life cycle of the bryozoan Bugula neritina. ISME J. 2007;1:693–702. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pavan M, Bo G. Pederin, toxic principle obtained in the crystalline state from the beetle Paederus fuscipes. Curt Phys Comp Oecol. 1953;3:307–312. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kellner RLL. Horizontal transmission of biosynthetic capabilities for pederin in Paederus melanurus (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae) Chemoecology. 2001;11:127–130. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piel J. A polyketide synthase-peptide synthetase gene cluster from an uncultured bacterial symbiont of Paederus beetles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14002–14007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222481399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chapela IH, Rehner SA, Schultz TR, Mueller UG. Evolutionary history of the symbiosis between fungus-growing ants and their fungi. Science. 1994;266:1691–1694. doi: 10.1126/science.266.5191.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mueller UG, Rehner SA, Schultz TR. The evolution of agriculture in ants. Science. 1998;281:2034–2038. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schlick-Steiner BC, et al. Specificity and transmission mosaic of ant nest-wall fungi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:940–943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708320105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poulsen M, Boomsma JJ. Mutualistic fungi control crop diversity in fungus-growing ants. Science. 2005;307:741–744. doi: 10.1126/science.1106688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Currie CR, Poulsen M, Mendenhall J, Boomsma JJ, Billen J. Coevolved crypts and exocrine glands support mutualistic bacteria in fungus-growing ants. Science. 2006;311:81–83. doi: 10.1126/science.1119744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gerardo NM, Jacobs SR, Currie CR, Mueller UG. Ancient host-pathogen associations maintained by specificity of chemotaxis and antibiosis. Plos Biol. 2006;4:1358–1363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Currie CR, Scott JA, Summerbell RC, Malloch D. Fungus-growing ants use antibiotic-producing bacteria to control garden parasites (vol 398, pg 701, 1999) Nature. 2003;423:461–461. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Currie CR, Scott JA, Summerbell RC, Malloch D. Fungus-growing ants use antibiotic-producing bacteria to control garden parasites. Nature. 1999;398:701–704. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Currie CR, Mueller UG, Malloch D. The agricultural pathology of ant fungus gardens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7998–8002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Riley MA, Chavan MA, editors. Bacteriocins: Ecology and Evolution. Springer; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roush RF, Nolan EM, Lohr F, Walsh CT. Maturation of an Escherichia coli ribosomal peptide antibiotic by ATP-consuming N-P bond formation microcin C7. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:3063–3069. doi: 10.1021/ja7101949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zamble DB, McClure CP, Penner-Hahn JE, Walsh CT. The McbB component of microcin B17 synthetase is a zinc metalloprotein. Biochemistry. 2000;39:16190–16199. doi: 10.1021/bi001398e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li YM, Milne JC, Madison LL, Kolter R, Walsh CT. From peptide precursors to oxazole and thiazole-containing peptide antibiotics: microcin B17 synthase. Science. 1996;274:1188–1193. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adams J, Kinney T, Thompson S, Rubin L, Helling RB. Frequency-dependent selection for plasmid-containing cells of Escherichia coli. Genetics. 1979;91:627–637. doi: 10.1093/genetics/91.4.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chao L, Levin BR. Structured habitats and the evolution of anticompetitor toxins in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6324–6328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Riley MA, Wertz JE. Bacteriocins: evolution, ecology, and application. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2002;56:117–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.161024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tagg JR, Dajani AS, Wannamaker LW. Bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:722–756. doi: 10.1128/br.40.3.722-756.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Riley MA, Goldstone CM, Wertz JE, Gordon DA. phylogenetic approach to assessing the targets of microbial warfare. J Evol Biol. 2003;16:690–697. doi: 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gordon DM, Oliver E, Littlefield-Wyer J. In: Bacteriocins: Ecology and Evolution. Riley MA, Chavan MA, editors. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Devireddy LR, Gazin C, Zhu X, Green MR. A Cell-surface receptor for lipocalin 24p3 selectively mediates apoptosis and iron uptake. Cell. 2005;123:1293–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nguyen T, et al. Exploiting the mosaic structure of trans-acyltransferase polyketide synthases for natural product discovery and pathway dissection. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:225–233. doi: 10.1038/nbt1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Piel J, et al. Antitumor polyketide biosynthesis by an uncultivated bacterial symbiont of the marine sponge Theonella swinhoei. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16222–16227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405976101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kawaide H. Biochemical and molecular analyses of gibberellin biosynthesis in fungi. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2006;70:583–590. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eyberger AL, Dondapati R, Porter JR. Endophyte fungal isolates from Podophyllum peltatum produce podophyllotoxin. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:1121–1124. doi: 10.1021/np060174f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Puri SC, Verma V, Amna T, Qazi GN, Spiteller M. An endophytic fungus from Nothapodytes foetida that produces camptothecin. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:1717–1719. doi: 10.1021/np0502802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jennewein S, Wildung MR, Chau M, Walker K, Croteau R. Random sequencing of an induced Taxus cell cDNA library for identification of clones involved in Taxol biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9149–9154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403009101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Williams DC, et al. Intramolecular proton transfer in the cyclization of geranylgeranyl diphosphate to the taxadiene precursor of taxol catalyzed by recombinant taxadiene synthase. Chem Biol. 2000;7:969–977. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhou X, et al. Screening of taxol-producing endophytic fungi from Taxus chinensis var. mairei. Prikl Biokhim Mikrobiol. 2007;43:490–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang J, et al. Taxol from Tubercularia sp. strain TF5, an endophytic fungus of Taxus mairei. FEMS. Microbiol Lett. 2000;193:249–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li JY, Strobel G, Sidhu R, Hess WM, Ford EJ. Endophytic taxol-producing fungi from bald cypress, Taxodium distichum. Microbiology. 1996;142:2223–2226. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-8-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Strobel G, et al. Taxol from Pestalotiopsis microspora, an endophytic fungus of Taxus wallachiana. Microbiology. 1996;142:435–440. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-2-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stierle A, Strobel G, Stierle D. Taxol and taxane production by Taxomyces andreanae, an endophytic fungus of Pacific yew. Science. 1993;260:214–216. doi: 10.1126/science.8097061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fujii I. In: Comprehensive Natural Products Chemistry. Barton DNK, Meth-Cohn O, editors. Elsevier; New York: 1999. pp. 409–441. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Poeaknapo C, Schmidt J, Brandsch M, Drager B, Zenk MH. Endogenous formation of morphine in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14091–14096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405430101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Donia MS, Ravel J, Schmidt EW. A global assembly line for cyanobactins. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:341–343. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schmidt EW, Obraztsova AY, Davidson SK, Faulkner DJ, Haygood MG. Identification of the antifungal peptide-containing symbiont of the marine sponge Theonella swinhoei as a novel delta-proteobacterium, “Candidatus Entotheonella palauensis”. Mar Biol. 2000;136:969–977. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schmidt EW, Bewley CA, Faulkner DJ. Theopalauamide, a bicyclic glycopeptide from filamentous bacterial symbionts of the lithistid sponge Theonella swinhoei from Palau and Mozambique. J Org Chem. 1998;63:1254–1258. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Taylor MW, Radax R, Steger D, Wagner M. Sponge-associated microorganisms: evolution, ecology, and biotechnological potential. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71:295–347. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00040-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bruck WM, Sennett SH, Pomponi SA, Willenz P, McCarthy PJ. Identification of the bacterial symbiont Entotheonella sp. in the mesohyl of the marine sponge Discodermia sp. ISME J. 2008;2:335–339. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schirmer A, et al. Metagenomic analysis reveals diverse polyketide synthase gene clusters in microorganisms associated with the marine sponge Discodermia dissoluta. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:4840–4849. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4840-4849.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Carroll AR, et al. Patellins 1–6 and trunkamide A: Novel cyclic hexa-, hepta- and octa-peptides from colonial ascidians, Lissoclinum sp. Aust J Chem. 1996;49:659–667. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Salomon CE, Faulkner DJ. Localization studies of bioactive cyclic peptides in the ascidian Lissoclinum patella. J Nat Prod. 2002;65:689–692. doi: 10.1021/np010556f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Long PF, Dunlap WC, Battershill CN, Jaspars M. Shotgun cloning and heterologous expression of the patellamide gene cluster as a strategy to achieve sustained metabolite production. Chembiochem. 2005;6:1760–1765. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jones BV, Marchesi JR. Transposon-aided capture (TRACA) of plasmids resident in the human gut mobile metagenome. Nat Methods. 2007;4:55–61. doi: 10.1038/nmeth964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jones BV, Marchesi JR. Accessing the mobile metagenome of the human gut microbiota. Mol Biosyst. 2007;3:749–758. doi: 10.1039/b705657e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Casas V, et al. Widespread occurrence of phage-encoded exotoxin genes in terrestrial and aquatic environments in Southern California. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;261:141–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dinsdale EA, et al. Functional metagenomic profiling of nine biomes. Nature. 2008;452:629–632. doi: 10.1038/nature06810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Andrianasolo EH, et al. Isolation of swinholide A and related glycosylated derivatives from two field collections of marine cyanobacteria. Org Lett. 2005;7:1375–1378. doi: 10.1021/ol050188x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bewley CA, Holland ND, Faulkner DJ. Two classes of metabolites from Theonella swinhoei are localized in distinct populations of bacterial symbionts. Experientia. 1996;52:716–722. doi: 10.1007/BF01925581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chavan M, Rafi H, Wertz J, Goldstone C, Riley MA. Phage associated bacteriocins reveal a novel mechanism for bacteriocin diversification in Klebsiella. J Mol Evol. 2005;60:546–556. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0263-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wertz JE, Riley MA. Chimeric nature of two plasmids of Hafnia alvei encoding the bacteriocins alveicins A and B. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:1598–1605. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.6.1598-1605.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]