INTRODUCTION

What would you do if you knew that by undergoing a minor medical intervention, you might save the life of another person? What if you could potentially save dozens of lives? How risky would the intervention have to be before you would even hesitate?

Vaccination is a minor medical procedure that reduces or eliminates the risk of contracting a targeted disease. If the disease is contagious, a vaccine can also reduce the risk of disease in people with whom the vaccinated person comes into contact. Vaccination is credited with preventing more illness and death over the past hundred years than any other medical advance.1

HEALTH CARE WORKERS AND THE SPREAD OF DISEASE

No one is at greater risk of contracting contagious diseases or of spreading them than health care workers. Those who work in hospitals regularly encounter patients as an essential part of their jobs. Disease-causing organisms can easily spread from patients to health care workers and then back to other patients on a hospital floor. The result is a group of health care workers who are out sick and unable to do their jobs, as well as a group of patients with a new disease that they did not have when they were admitted. The solution, in the view of most public health officials, is to have all health care workers vaccinated.

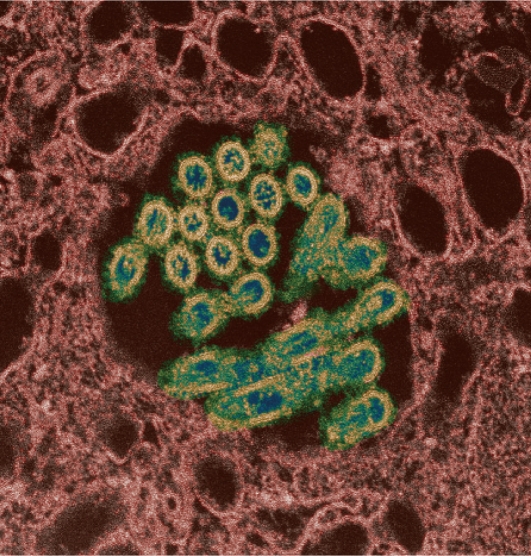

Vaccination of health care professionals has recently grabbed the attention of public health officials and much of the public with the spread of the H1N1 flu virus. The World Health Organization (WHO) has issued dire predictions of a pandemic that could cause fatalities throughout the world.2 The President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology has warned that the disease could affect half of the population in the U.S.3 It is highly contagious, and infected people can spread the virus for several days before they even know they have it.

H1N1 virus (swine flu) showing virions.

However, many health care workers resist vaccination. Nationwide, fewer than half receive vaccines each year for the more common seasonal flu.4 Uptake of the H1N1 vaccine is not expected to be much different. To achieve higher vaccination rates, a more aggressive approach is needed than simply informing health care workers and hoping they will receive vaccines on their own.

ATTEMPTS AT PROMOTING VOLUNTARY VACCINE COMPLIANCE

Hospitals have tried numerous techniques to increase voluntary immunization among their patient-care staffs. Some hospitals use roving carts that bring vaccines to nursing stations, or vaccines might be brought to staff meetings. In some facilities, vaccine decliners must sign statements acknowledging the risk they are assuming for themselves and for their patients, or they might have to wear surgical masks during flu season. The goal of all these measures is to make vaccination as convenient—and avoidance of vaccination as inconvenient—as possible.

Unfortunately, while these efforts to achieve voluntary compliance tend to increase vaccine uptake somewhat, they still leave vaccination rates below 50%.5 The only approach that has generated near-total compliance is mandatory vaccination consisting of an ultimatum to health care workers that they either receive a vaccine or lose their job. Limited exceptions are permitted for individuals known to be at heightened risk for side effects, such as allergies to vaccines, and for those with clear religious objections.

VACCINATION MANDATES AND THEIR OPPONENTS

Mandatory vaccination requirements have become increasingly prevalent as the threat of an H1N1 pandemic has intensified. A number of hospitals across the country, including Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Emory Hospital in Atlanta, and all 273 facilities of Hospital Corporation of America, have instituted such rules for their own personnel.6 Additional facilities may join them.

New York State was the first in the nation to try to mandate vaccination as a matter of law, but the effort proved to be short-lived. The Department of Health issued a rule last August that would have barred workers who declined either seasonal or H1N1 influenza vaccination from assignments involving patient contact in any hospital, outpatient clinic or home-care program.7 However, a group of nurses sued and obtained a restraining order suspending enforcement. Subsequently, the Department, citing vaccine shortages, withdrew the proposal.8 It is not clear whether other states will attempt similar measures.

For the most part, unions representing nurses have been vocal in opposing vaccine mandates.9 Although they generally support voluntary vaccination and strongly encourage their members to comply, they believe that each health care worker should be entitled to make his or her own decision. They point out that all vaccines can pose risks. Even for people without allergies, hazards may lurk in additives, such as thimerosal, a mercury-based preservative used in some vaccines.

Moreover, an injection that produces no immediate harm may still pose longer-term risks. Mandate opponents point to the experience with the swine flu vaccine that was produced in 1976, which was linked to an increased risk of Guillain–Barré syndrome, a paralytic nerve condition.10 There is also no guarantee that a new vaccine will prove effective.

Mandate opponents also frame the issue as one of rights. Should health care workers have less freedom than others to decide what health risks they choose to accept? Should entering the nursing profession turn a person into a second-class citizen? In the end, mandates may have the unfortunate effect of driving some people away from working in health care.

THE LEGAL STATUS OF MANDATES

The power of the government to mandate vaccination has long been recognized by the Supreme Court. In the landmark 1905 case of Jacobson v. Massachusetts, the Court upheld an ordinance in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that required all adult citizens to be vaccinated against smallpox in the wake of an epidemic.11 The court found that notwithstanding the Constitution’s guarantee of liberty, every person may be subject to “manifold restraints” when needed “for the public good.” This broad ruling gives health care workers limited legal ground to object.

Moreover, most states recognize the doctrine of employment-at-will, under which employers can terminate a worker for any reason as long as a prohibited motivation, such as race or disability status, is not involved. In the absence of a proscribed rationale, vaccination can be used as a condition of continued employment.

There is an exception to the employment-at-will doctrine for collective bargaining agreements that limit an employer’s hiring discretion. In 2006, the Washington State Nurses Association sued Virginia Mason Hospital in Seattle, which sought to require nurses to receive seasonal flu vaccine. The union claimed that a collective bargaining agreement prohibited new workplace rules without its consent. An arbitrator upheld the union’s right to veto the vaccine requirement, and the decision was affirmed in court.12 However, the hospital has recently reinstituted the mandate for all employees except unionized nurses.13

ARGUMENTS FOR MANDATES

Public health officials frame the issue of vaccine mandates for health care workers as one of patient safety. Studies have shown higher patient death rates in hospitals with a smaller percentage of vaccinated employees.14 From this perspective, the freedom of workers to make decisions regarding their own health should carry less weight than the well-being of people who depend on them for care. The goal of public health is to safeguard the population at large, and this is where priorities must lie.

Mandate advocates also see the risk of vaccines as minimal. The most significant concern is with people who are allergic to eggs, because vaccine production has traditionally required their use to incubate virus stains. However, susceptible people can easily be screened out; in addition, new cell-based manufacturing techniques are obviating the need for eggs. Some batches of H1N1 vaccine have been manufactured using this approach. Thimerosal is used in H1N1 vaccines that are injected but not in vaccines administered nasally. However, even though mercury is associated with severe health effects, this vaccine preservative has never been linked to adverse outcomes.15 Moreover, because the vaccine uses an inactivated or a severely weakened virus, there is no chance that it will transmit the flu.

A guarantee of complete vaccine safety is never possible, but protection of public health often involves a balancing of risks. Seasonal flu causes an estimated 36,000 deaths in the U.S. each year.16 Even though the virulence of H1N1 is not yet known, it could prove to be even more lethal. This hazard is considered to far outweigh the much smaller risk of adverse vaccine effects.

CONCLUSION: A BALANCE OF RIGHTS

Certainly, health care workers have rights that must be respected.17 Mandated medical interventions, such as vaccination, should never be imposed capriciously; however, patient contact involves unavoidable risks and special obligations. Professionals who care for patients accept an overriding ethical imperative embodied in the Hippocratic Oath that new physicians take—first, do no harm. Unvaccinated workers who spread the flu can cause tremendous harm. This is especially true when vulnerable patients, such as those in intensive-care units, are involved.

Patients should have the right to expect that their hospital will take every reasonable precaution to protect them from developing a new disease that they did not have upon admission. With regard to the flu and many other contagious diseases, vaccination is the best way to honor this right. Although voluntary compliance by health care professionals would be preferable to mandates, its lack of effectiveness, at least so far, leaves hospitals and public health officials with little choice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Ten great public health achievements—United States, 1900–1999 MMWR Wkly 19994812241–243.Available at: www.cdc.gov/MMWR/preview/mmwrhtml/00056796.htm Accessed October 8, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) Assessing the severity of an influenza pandemic, May 11, 2009. Available at: www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/assess/disease_swineflu_assess_20090511/en/index.html Accessed October 8, 2009.

- 3.President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. Report to the President on U.S. Preparations for 2009—H1N1 Influenza, August 7, 2009. Available at: www.whitehouse.gov/assets/documents/PCAST_H1N1_Report.pdf Accessed October 8, 2009.

- 4.Hitt E.States, institutions requiring flu shots for healthcare workers Medscape TodaySeptember 17, 2009. Available at: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/709080 Accessed October 8, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNeil DG, Zraick K.New York health care workers resist flu vaccine rule The New York TimesSeptember 21, 2009.

- 6.Caplan A.Health workers: Get shots or get another jobMSNBC, October 8, 2009. Available at: www.msnbc.msn.com/id/33210502/ns/health-health_care Accessed October 8, 2009.

- 7.Hartocollis A.State requires flu vaccination for caregivers The New York TimesAugust 19, 2009.

- 8.Hartocollis A, Chan S.Flu vaccine requirement for health workers is lifted The New York TimesOctober 23, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox L.Some nurses say no to mandatory flu shotsABC News, October 2, 2009. Available at: http://abcnews.go.com/Health/SwineFluNews/mandatory-flu-vaccines-upset-nurses/story?id=8727353 Accessed October 8, 2009.

- 10.Schonberger LB, Bregman DJ, Sullivan-Bolyai JZ, et al. Guillain–Barré syndrome following vaccination in the National Influenza Immunization Program, United States, 1976–1977. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110(2):105–123. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobson v Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11 (1905).

- 12.Virginia Mason Hospital v Washington State Nurses Association, 511 F.3d 908 (9th Cir. 2007).

- 13.Song KM.Flu shots mandatory at Virginia Mason The Seattle TimesOctober 2, 2009.

- 14.Tosh PK, Poland GA.Healthcare worker influenza immunizationMedscape CME, December 21, 2007. Available at: http://cme.medscape.com/viewarticle/567336 Accessed October 8, 2009.

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vaccine safety, February 8, 2008. Available at: www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/updates/thimerosal.htm Accessed October 8, 2009.

- 16.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:179–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Field R, Caplan A. A proposed ethical framework for vaccine mandates: Competing ethical values and the case of HPV. Kennedy Institute Ethics J. 2008;18(2):111–124. doi: 10.1353/ken.0.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]