Introduction

Nutrigenomics represents a suitable approach to cardiovascular medicine, potentially enabling both, better prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) through optimization of individuals’ dietary intakes. However, Nutrigenomics is still developing its research methodology and learning from its achievements and its shortcomings. Its foundations have been laid allowing us to validate its theoretical basis and, from there, to pursue research aimed to obtain a higher level of scientific evidence needed for its effective translation to clinical practice. This review discusses these aspects and summarizes the literature pertaining to gene-diet interactions related to intermediate and final CVD phenotypes.

Despite their multifactorial complexity, CVD have been the group of diseases in which most progress has been made on the knowledge of their genetic risk factors, both in identifying candidate genes through the classic approach based on the protein function and through the recent genome wide association studies (GWAs). Current knowledge regarding CVD genetic factors is summarized in several recent reviews (1–5). This has been possible due to the prior characterization of multiple intermediate phenotypes linked to those diseases, among which are plasma lipid concentrations, plasma glucose and related parameters, markers of inflammation and endothelial damage, oxidative stress, blood pressure, anthropometric measurements and even phenotypes obtained by means of non-invasive imaging techniques such as measuring the intima-media thickness of artery walls (6,7). The relative ease of measuring these intermediate phenotypes and the specific understanding of them as risk factors, has allowed many studies to be carried out aimed at identifying gene and genetic variants related to each of them and so obtaining a more detailed knowledge of the numerous genes involved in the final phenotypes of CVD (i.e., coronary heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, peripheral cardiovascular diseases).

In spite of the spectacular advances made over recent decades in the discovery of genes and gene variants involved in the intermediate and final phenotypes of CVD, we still have a very incomplete knowledge of all genes and genetic variants that are providing such genetic susceptibility. Moreover, in that search for genetic susceptibility, the interaction with environmental factors must be taken into account. Therefore, a genetic variant will not always present a greater risk of disease, but its effects will be modified by the environmental factors (i.e., tobacco smoking, physical activity, dietary intake) that interact with it. Among the environmental factors, diet may be the most directly involved in the genetic modulation of the different intermediate and final phenotypes of CVD. However, we still need to find out how certain dietary components may modulate the risk conferred by genetic susceptibility due to variation in one or more genes involved in the etiology of CVD. This knowledge is not only crucial for contributing to better primary prevention of CVD, but also for increasing the effectiveness of the treatment once the altered phenotypes have been diagnosed. Furthermore, from the Public Health point of view, the understanding of really important gene-diet modulations could help to profile the general dietary recommendations for each population.

Diet and CVD

It should be borne in mind that diet has traditionally been considered as one of the main risk factors in the etiology of CVD, a significant percentage of the increase of the incidence of these diseases being attributed to the harmful changes towards less healthy diets that has taken place in recent decades in different geographical areas (8,9). However, despite various initiatives carried out by different national and international organizations, focusing on making nutritional recommendations to the population in order to improve food intake patterns, success has not been forthcoming in reducing the risk of those diseases. There are many factors involved in this failure, among them, the inherent difficulties in changing behaviors, fashions, mass media pressure, sedentarism, deficient interventions in nutritional education, etc (10–11).

What has also had an impact on the creation of a certain degree of skepticism among the general public is the absence of clear scientific evidence on which is the best diet to prevent or treat the different altered phenotypes that are involved in CVD (10). It must be admitted that often contradictory nutritional recommendations, based on the results of studies with little external validity and on different kinds of commercial interest, have been formulated over recent decades (12–15). Therefore, an intense debate has been taking place on the best composition of macronutrients in the diet to prevent or treat CVD, especially as regards the percentage provided by total fat and its different fatty acids (16–21), and even on the origin of those fatty acids; as the monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) derived from olive oil as opposed to MUFA derived from meat and other foods of animal origin (21,22). Likewise, there is much controversy over the best origin and type (omega-6 and omega-3 series) of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) (21,23) in preventing or treating CVD. Especially lively has been the debate on the virtues of a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet as opposed to a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet in controlling body-weight and related cardiovascular risk factors (24, 25). Faced with this diversity of effects and recommendations, it is not surprising that various authors insist that there is no perfect diet (10), but this diet may vary depending on individual´s characteristics and the results that the individual wishes to achieve, and hence, it is necessary to delve deeper into the study of these inter-individual differences (26).

Inter-individual differences in response to diet and Nutritional Genomics

The different responses to diet depending on the particular characteristics of an individual is not a new observation, but has already been widely documented in dozens of studies (27–28). For example in 1965 Keys et al (29), in their study on the effects of diet in plasma concentrations of cholesterol, stressed the dramatic differences between individuals, concluding that it was the “intrinsic characteristics” of the individual that motivated the different lipid responses to the same dietary intervention. Having admitted that each individual (or in practice, each group of individuals) may respond differently to the same diet, it becomes crucial to identify the factors defining such differential response. Among the many potential factors, genetic variability could play a significant role (30,31). Accordingly, studies have been undertaken to determine whether genetic variants, mainly single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), can explain those differences. These gene-diet modulations may also help to explain the different phenotypes observed for a given genotype, such as those observed in some monogenic forms of CVD (32,33). Thus, the same gene variant may be associated with wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, ranging from no symptoms at all to severe CVD. Therefore, in addition to potential epistasis, other non-genetic factors (among which we could emphasize diet) may be important in modifying the clinical phenotype, either by exacerbating or protecting against the diseased phenotype.

Nutritional Genomics came into being at the beginning of the 90s (31). The main goal was to gain knowledge about the interaction between dietary factors and the genome that modulate phenotypic expression. This knowledge could explain the genetic basis for the inter-individual response to diet, as well as the reasons for the different clinical phenotypes observed for the same genetic variant. This discipline has been gathering momentum for the last two decades to become a significant player in cardiovascular research. Table 1 show the main reviews published on the subject, stressing their particular emphasis (26, 31,33–59), such as basic concepts of the discipline; potential applications in different areas of disease prevention and treatment; Public Health perspective; training needs for dieticians and their potential involvement; advantages and drawbacks of dietary individualization; consumers perceptions; the role of the food industry; and the ethical and legal aspects associated with this new field.

Table 1.

Main reviews published on Nutritional Genomics

| Authors | Subject | Journal, year | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hegele | General review on the gene-environment interactions in atherosclerosis, with a section devoted to gene-diet interactions in lipid metabolism |

Mol Cell Biochem. 1992 |

34 |

| Ordovas et al |

Review of the influence of different gene-variants on lipid response to diet |

Atherosclerosi s. 1995 |

35 |

| Tall at al | Report of an NHLBI working group stressing the importance of researching gene-diet interactions in the development of atherosclerosis, and proposing three approaches to examine this concern. The first approach utilizes animal models; the second approach involves the evaluation of the genes in specific physiological processes, and the third is to extend these studies to human populations. |

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997 |

36 |

| Pérusse et al |

Review of gene-diet interactions in obesity, analyzing both studies in animals and humans |

Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 |

37 |

| Elliott R et al |

Brief review on the Nutritional Genomics concept and its application to disease prevention and treatment |

BMJ, 2002 | 38 |

| van Ommen et al |

Developing the concept of systems biology applied to nutrition and reflections on the future of genomics, proteomics and metabolomics in nutrigenomics |

Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2002 |

39 |

| German et al |

Stressing the importante of metabolomics and its application to nutrition studies in order to better understand the effects of diet on the genome and health |

J Nutr. 2002 | 40 |

| Müller et al |

Wide-ranging review on the concept of nutrigenomics as the application of high-throughput genomics tools in nutrition research. Review of the bases of all omics and their application to prevent diet-related diseases |

Nat Rev Genet. 2003 |

41 |

| Ordovas et al |

Review of the concepts of nutrigenomics and nutrigenetics and their application in cardiovascular genomics |

Curr Opin Lipidol. 2004 |

42 |

| Kaput et al |

Reflexion on the applications of Nutritional Genomics in a new area for nutrición |

Physiol Genomics. 2004 |

43 |

| Ordovas et al |

Wide review of the concept of nutritional genomics and its sub-disciplines applied to the prevention and treatment of disease. Methodological aspects of undertaking nutritional genomic studies in humans and various examples applied to CVD, cancer and other diseases. |

Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet |

31 |

| Chadwic k R |

Review on how the individualism that nutritional genomics proposes can be integrated in Public Health |

Proc Nutr Soc. 2004 |

44 |

| Kaput J | Importance of the strategic international alliances to harness nutritional genomics for public and personal health |

Br J Nutr. 2005 |

45 |

| Corella D et al |

Review of the main polymorphisms that influence lipid metabolism and their interaction with dietary factors |

Annu Rev Nutr. 2005 |

33 |

| Trujillo et al |

Their objectives were to acquaint nutritional professionals with terms relating to "omics," to convey the state of the science, to envisage the possibilities for future research and technology, and to recognize the implications for clinical practice |

J Am Diet Assoc. 2006 |

46 |

| Ordovas et al |

Metagenomics: the role of the microbiome in cardiovascular diseases |

Curr Opin Lipidol. 2006 |

47 |

| Gallou- Kabani et al |

Review of the epigenetic mechanisms involved and how they influence health. Also how diet can have either a positive or negative influence on the epigenome |

Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007 |

48 |

| Castle D et al |

Ethical, legal and social issues in nutrigenomics: the challenges of regulating service delivery and building health professional capacity |

Mutat Res. 2007 |

49 |

| Low et al | Understanding diet-gene interactions: lessons from studying nutrigenomics and cardiovascular disease |

Mutat Res. 2007 |

50 |

| Brown et al |

The relevance of nutritional genomics to the food industry is revised and examples given on how this science area is starting to be leveraged for economic benefits and to improve human nutrition and health. |

Br J Nutr. 2007 |

51 |

| Bergman n et al |

An overview of the ethical issues in nutrigenomics research and personalized nutrition. |

Annu Rev Nutr. 2008 |

52 |

| Lovegrov e et al |

Review on the application of nutrigenomics in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases |

J Hum Nutr Diet. 2008 |

26 |

| Subbiah MT |

Understanding the nutrigenomic definitions and concepts at the food-genome junction |

OMICS. 2008 | 53 |

| Stover et al |

Genetic and epigenetic contributions to human nutrition and health: managing genome-diet interactions |

J Am Diet Assoc. 2008 |

54 |

| Whelan K et al |

Genetics and diet-gene interactions: involvement, confidence and knowledge of dieticians |

Br J Nutr. 2008 |

55 |

| McCabe- Sellers et al |

Review of how personalizing nutrigenomics research through community based participatory research and omics technologies |

OMICS. 2008 | 56 |

| Tepper | Nutritional implications of genetic taste variation: the role of PROP sensitivity and other taste phenotypes |

Annu Rev Nutr. 2008 |

57 |

| Ferguson | Nutrigenomic approaches to functional foods | J Am Diet Assoc. 2009 |

58 |

| Shen et al | Review on gene-diet interactions and other gene- environment interactions that affect high-sensitivity C-reactive protein concentrations |

Clin Chem. 2009 |

59 |

Research into Nutritional Genomics is a leading subject in numerous calls for national and international projects, and relevant research networks, such as the so-called NuGO (Nutrigenomics Organisation), have been launched. NuGO is a European-funded Network of Excellence, the full title of which is 'The European Nutrigenomics Organisation: linking genomics, nutrition and health research', which is carrying out cutting-edge research into all the omics related to nutrition and health as well as into the ethical aspects derived. In the rise of Nutritional Genomics, it is also important to stress the creation of numerous research institutes in various countries dedicated to this new discipline. Among them, for example are: The Cornell Institute for Nutritional Genomics at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York; The Center of Excellence in Nutritional Genomics, California (CA) that is funded by an award from the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD); o the recently launched Salk Center for Nutritional Genomics in La Jolla, CA. Besides these institutes, programs or laboratories devoted to research into Nutritional Genomics have been created in most nutrition research centers. As investment and scientific training in this discipline has increased, so too has the number of scientific publications centered on that field and in an exponential way.

Nonetheless and despite the huge promises made in numerous articles on this subject, we need to underscore that Nutritional Genomics is a discipline still in its infancy, and more progress needs to be done before practical tools can be developed for the prevention and treatment of CVD. Given the novelty of this discipline, there is still some confusion about the delimitation of its concepts, as often the terms of Nutritional Genomics, Nutrigenetics and Nutrigenomics, are used as synonyms. Nutritional Genomics implies greater generalization referring to the joint study of nutrition and the genome including all the other omics derived from genomics: transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics. The terms Nutritional Genomics would be equivalent to the wide ranging term of gene-diet interaction. Within the wide framework of the concept of Nutritional Genomics we can distinguish two sub-concepts: Nutrigenetics and Nutrigenomics. Currently, there is a wide consensus on considering Nutrigenetics as the discipline that studies the different phenotypic response to diet depending on the genotype of each individual. The term Nutrigenomics is subject to a greater variability in its delimitation, but it seems that there is a certain consensus in considering Nutrigenomics as the discipline which studies the molecular mechanisms explaining the different phenotypic responses to diet depending on the genotype, studying how the nutrients regulate gene expression, how they affect polymorphisms in this regulation, and how these changes are inter-related with proteomics and metabolomics. However, despite this specific delimitation, there is also a widespread line of thought that uses the term Nutrigenomics as equivalent to Nutritional Genomics. This wider interpretation of the Nutrigenomics concept is the one that we shall use in this review.

The present of Nutrigenomics in CVD

Notwithstanding the numerous studies published in which statistically significant gene-diet interactions have been found determining different intermediate (Table 2) (60–81) or clinical CVD outcomes (Table 3) (82–94), the main problem that Nutrigenomics faces is the lack of replication of the initially reported gene-diet interactions. This precludes its present application in the prevention and treatment of CVD. Hence it is now essential to increase the consistency of results by implementing gene-diet interaction replication studies in various populations. When the results are available it is also essential to carry out quantitative meta-analyses of the gene-diet interactions in order to check the homogeneity or heterogeneity of the effect and to obtain overall association measurements. It is also crucial to increase the evidence level of the replicated gene-diet interactions found in observational studies by undertaking nutritional intervention studies.

Table 2.

Selected studies showing statistically significant gene-diet interactions in determining intermediate CVD phenotyes

| Authors | Phenotype | Description of the gene-diet interaction | Year, Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lopez- Miranda et al (*) |

Postprandial LDL-C | The -75G/A APOA1 SNP influenced the postprandial LDL-C response to MUFA. After consumption of a high MUFA diet, significant increases in LDL-C were noted in carriers of the A alle but not in G/G subjects |

1994, (60) |

| Jansen et al (*) |

Postprandial LDL-C | Postprandial LDL-C response to dietary fat is influenced by the 347Ser mutation of APOA4. Carriers of the 347Ser allele presented a greater decrease in LDL-C when they were switched from the SFA to the NCEP type 1 diet than homozygous the 347Thr allele. |

1997, (61) |

| D'Angelo et al (*) |

Plasma homocysteine | The C677T SNP in the MTHFR gene interacted with folate and vitamin B12 levels in determining plasma homocysteine concentrations |

2000, (62) |

| Campos H et |

VLDL and HDL-C | The APOE genotype interacted with saturated fat in determining VLDL and HDL-C concentrations (higher VLDL and lower HDL- C in E2 carriers with a high fat) |

2001, (63) |

| Luan J et al | BMI and fasting insulin |

An interaction was found between the PUFA:saturated fat ratio and the Pro12Ala PPARG polymorphism for both BMI and fasting insulin. With a low ratio, the BMI in Ala carriers was greater than that in Pro homozygotes, but when the dietary ratio was high, the opposite was seen. |

2001, (64) |

| Corella et al | Fasting plasma LDL-C concentrations |

Alcohol intake interacted with the APOE SNP in determining LDL-C in men. In E2 subjects, LDL-C was significantly lower in drinkers than in nondrinkers but was significantly higher in drinkers than in nondrinkers in E4 subjects. |

2001, (65) |

| Leeson et al | Endothelium- dependent, flow- mediated brachial artery dilatation (FMD) and endothelium- independent dilatation response |

An endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) SNP (Glu298Asp) interacted with dietary omega-3 in determining endothelial responses. Omega-3 were positively related to FMD in Asp298 carriers but not in Glu298 homozygotes. |

2002, (66) |

| Ordovas et al |

HDL-C concentrations and HDL particle size |

The -514C>T LIPC polymorphism interacted with dietary fat in determining HDL-related measures. T allele was associated with significantly greater HDL-C concentrations and large HDL size only in subjects consuming <30% of energy from fat. |

2002, (67) |

| Brown et al | Total cholesterol and LDL-C |

The T-455C, T-625del SNP in the APOC3 gene interacted with saturated fat intake in determining total cholesterol and LDL-C. In homozygotes for the APOC3-455T-625T alleles, saturated fat intake was associated with an increase in total and LDL-C: No association was found among carriers of the APOC3-455C- 625del allele. |

2003, (68) |

| Memisoglu et al |

Body mass index | The Pro12Ala SNP in the PPARG gene interacted with fat intake in determining BMI. Among Pro/Pro individuals, those in the highest quintile of total fat intake, had significantly higher BMI compared with those in the lowest quintile whereas among 12Ala carriers there was no association between dietary fat intake and BMI. In contrast, MUFA intake was not associated with BMI among Pro/Pro women but was inversely associated with BMI among 12Ala carriers |

2003, (69) |

| Dwyer et al | Carotid-artery intima- media thickness, and markers of inflammation |

Increased dietary arachidonic acid significantly enhanced the apparent atherogenic effect of the 5-lipoxygenase genotype, whereas increased dietary intake of n-3 fatty acids blunted the effect, suggesting that omega-6 promote, whereas marine omega-3 inhibit, leukotriene- mediated inflammation |

2004, (70) |

| Dedoussis et al |

Plasma Homocysteine | The Mediterranean diet score was not significantly associated with homocysteine concentrations. However, a gene-diet interaction with the C677T SNP in the MTHFR was found. Higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with reduced homocysteine concentrations in carriers of the T allele but not in those with the CC genotype. |

2004, (71) |

| Tai et al | Fasting triglycerides and apolipoprotein C- III (apoC-III) |

The L162V polymorphism at the PPARA gene interacted with dietary PUFA intake in determining fasting triglycerides and apoC-III concentrations. The 162V allele was associated with greater TG and apoC-III concentrations only in subjects consuming a low-PUFA diet |

2005, (72) |

| Zhang et al | Blood pressure levels and hypertension. |

The angiotensin I-converting enzyme insertion- deletion polymorphism (ACE I/D) interacted with dietary salt intake. In the ID+II genotype, hypertension was increased by high salt intake, while in the DD genotype it was not. The interaction was more prominent in the overweight group. |

2006, (73) |

| Corella et al | Insulin resistance | The PLIN 11482G-->A/14995A-->T polymorphisms (in high linkage disequilibrium) interacted with saturated fat and carbohydrates in determining HOMA-IR in Asian women. These interactions were in opposite directions. Women in the highest SFA tertile had higher HOMA-IR than women in the lowest only if they were homozygotes for the PLIN minor allele. |

2006, (74) |

| Robitaille et al |

Plasma lipid, blood pressure, waist circumference |

64 SNP were studied. ThePro12Ala polymorphism in the PPARA, interacted with fat intake in determining waist circumference. The APOE genotype in interaction with fat intake determined diastolic and systolic blood pressure. The ghrelin Leu72Met polymorphism also interacted with dietary fat in its relation to waist circumference and triglycerides. |

2007, (75) |

| Corella et al | Body mass index and obesity |

The -1131T>C APOA5 SNP interacted with fat intake in determining BMI and obesity risk. In subjects homozygous for the -1131T major allele, BMI increased as total fat intake increased. Conversely, this increase was not present in carriers of the -1131C minor allele. |

2007, (76) |

| Sofi et al | Plasma lipoprotein (Lp) (a) concentrations |

The LPA 93C>T SNP interacted with dietary fish intake in determining Lp(a) concentrations. The decreasing effect of fish consumption on Lp(a) concentrations was higher in TT subjects. |

2007, (79) |

| Pérez- Martínez et al (*) |

Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor Type 1 concentrations |

The plasminogen Activator Inhibitor Type 1 (PAI-1) -675 4G/5G polymorphism interacted with dietary saturated fat in determining PAI-1 concentrations. Carriers of the 4G allele showed a decrease in PAI-1 concentrations after the MUFA diet, compared with the SFA- rich and carbohydrate-rich diets |

2008, (78) |

| Norat et al | Blood pressure | The M235T polymorphism in the AGT gene interacted with dietary salt intake in determining blood pressure. The regression coefficient for systolic blood pressure associated with each unit of sodium for each of the MT and TT genotypes was approximately double that for the MM homozygotes. |

2008, (79) |

| Nettleton et al |

Plasma HDL-C | A common SNP in the angiopoietin-like 4 gene (ANGPTL4[E40K]) interacted with carbohydrates in determining plasma HDL-C concentrations. In men, the inverse association between carbohydrate and HDL-C was stronger in A allele carriers than non-carriers |

2009, (80) |

| Kanoni et al | Plasma zinc, interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-8 (IL-8) |

The -174G/C polymorphism in the IL-6 gene interacted with a dietary zinc score in determining IL-6 concentrations. A higher zinc score was associated with significantly higher plasma IL-6 levels in GG individuals. |

2009, (81) |

Intervention study in which short-term diets or specific components have been evaluated. In the other studies habitual dietary intakes were analyzed.

Table 3.

Selected studies showing statistically significant gene-diet interactions in determining final CVD phenotyes

| Authors | Phenotype | Description of the gene-diet interaction | Year, Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fumeron et al |

Myocardial infarction |

Alcohol consumption interacted with the CETP-TaqIB SNP in determining myocardial infarction. The increasing effect of the B2 allele on plasma HDL-C was absent in subjects drinking < 25 grams/d of alcohol but increased commensurably, with higher values of alcohol consumption. Accordingly, the OR for myocardial infarction of B2B2 subjects decreased from 1 in nondrinkers to 0.34 in those drinking 75 grams/d or more. |

1995, (82) |

| Markus et al |

Ischemic cerebrovascular disease |

The C677T SNP in the MTHFR gene interacted with serum folate concentrations in determining the risk of ischaemic stroke. The TT genotype was a risk when serum folate was low. |

1997, (83) |

| Yoo et al | Coronary artery disease |

The C677T SNP in the MTHFR gene interacted with a low folate status in determining coronary artery disease risk. |

2000, (84) |

| Hines et al |

Myocardial infarction |

Alcohol consumption interacted with the alcohol dehydrogenase type 3 (ADH3) SNP in determining myocardial infarction. Moderate drinkers who are homozygous for the slow-oxidizing ADH3 allele (gamma2) have higher HDL levels and a substantially decreased risk of myocardial infarction. |

2001, (85) |

| Yates et al. |

Thrombotic event | The C677T SNP in the MTHFR gene interacted with B- vitamin nutritional in determining homocysteine levels and risk for a thrombotic event. |

2003 (86) |

| Younis et al |

Coronary heart disease |

Significant alcohol-ADH3 genotype interaction on coronary heart disease risk was observed, with gamma2 homozygotes, who were modest drinkers, displaying 78% risk reduction compared to gamma1 homozygotes. |

2005 (87) |

| Cornelis et al |

Myocardial infarction |

A cytochrome P450 1A2 (CYP1A2) polymorphism interacted with coffee intake in determining myocardial infarction risk. Individuals who are homozygous for the CYP1A2*1A allele are "rapid" caffeine metabolizers, whereas carriers of the variant CYP1A2*1F are "slow" caffeine metabolizers. Intake of coffee was associated with an increased risk of nonfatal myocardial infarction only among individuals with slow caffeine metabolism |

2006, (88) |

| Volcik et al |

Coronary heart disease |

The PON1 polymorphism interacted with heavy alcohol intake in determining coronary heart disease in black men. |

2007, (89) |

| Yang et al |

Myocardial infarction |

The APOE SNP interacted with saturated fat intake in determining myocardial infarction. E2 and E4 gene variants increase susceptibility to myocardial infarction in the presence of high saturated fat diet. |

2007, (90) |

| Ruiz- Narvaez et al |

Myocardial infarction |

The Pro12Ala PPARG polymorphism interacted with PUFA intake to affect the risk of myocardial infarction. The protective effect of PUFA intake on myocardial infarction is attenuated in carriers of the Ala12 allele of PPARG. |

2007, (91) |

| Cornelis et al |

Myocardial infarction |

Cruciferous vegetables are a major dietary source of isothiocyanates. Isothiocyanates induce glutathione S- transferases (GSTs), polymorphic genes. The GST genotypes modified the association between cruciferous vegetable intake and the risk of myocardial infarction. Compared with the lowest tertile of cruciferous vegetable intake, the highest tertile was associated with a lower risk of MI among persons with the functional GSTT1*1 allele but not among those with the GSTT1*0*0 genotype. |

2007, (92) |

| Allayee et al |

Myocardial infarction |

A 5-Lipoxygenase (5-LO) SNP interacted with dietary arachidonic acid (AA) in determining myocardial infarction. The variant alleles were associated with greater risk of myocardial infarction in the context of a high-AA diet. |

2008, (93) |

| Jensen et al |

Myocardial infarction |

The CETP-TaqIB SNP interacted with alcohol consumption in determining myocardial infarction risk. Alcohol consumption was associated with lower risk in carriers of the B2 alleles |

2008, (94) |

All of these were observational studies and habitual dietary intake was analyzed

Major methodological considerations in studies of gene-diet interactions

To increase the validity of individual studies in nutrigenomics is critical to control the potential information and selection bias that may contribute to hinder replication. In experimental studies these potential bias are minimized. However, the difficulty of conducting dietary intervention studies in large samples is a current limitation in nutrigenomics. In observational studies (i.e., cohort, case-control, cross-sectional), the researcher does not provide the diet and has to gather nutritional information from dietary questionnaires. Therefore, high-quality dietary information in these epidemiological studies is crucial for minimizing information bias. Traditional dietary instruments (i.e., diet records, 24-h recalls, food-frequency questionnaires) as well as specific biomarkers of intake should be improved and tailored to the specific gene-diet interaction measured. In addition, it is still unclear what kind dietary information is more relevant in nutrigenomics. Should we be using nutrients, foods or dietary patterns? There may not be a single solution, and may depend on the specific aims and hypothesis being investigated. More information related to these methodological issues can be found in some previous reviews (31, 33).

Bearing in mind the difficulty of measuring diet in observational studies, it would be necessary to standardize the design of new studies in the field of cardiovascular genomics in order to clearly define the variables to be measured, both for diet as well as for potential confounding variables (i.e., sex, age, tobacco smoking, physical activity, education, obesity, and ethnicity or genetic admixture).

To palliate some of the limitations of classical methods to measure dietary intake, several efforts are currently in place. Some of them focus on standardization of data acquisition across studies. Along these lines, the PHENX (consensus measures for phenotypes and exposures) project (https://www.phenx.org/) has been launched by the National Human Genome Research Institute to facilitate the integration of genetics and epidemiologic research, which aims to standardized measurement protocols for inclusion in GWAS and other large-scale genomic studies to enable valid cross-study comparisons and analyses (95). In addition, other efforts aim to improving existing instruments to more precisely evaluate food intake including the use of new information and communication technologies (96).

The clinical characteristics of the populations would also have to be controlled and stratified appropriately: General population, diabetics, dyslipemics, subjects with hypertension or CVD must be clearly differentiated. Likewise, standardization should also include cut-off points for food intake and/or dietary components. Without this previous standardization, replication of gene-diet interactions will be very difficult to achieve. Although, this seems to be a minor problem, we cannot forget that nutrigenomic studies also require a good quality control and validity of the genetic determinations.

Consistency of the results obtained from association studies in cardiovascular genomics and gene-diet interactions

The same consistency demanded of Nutrigenomics studies is now being required of association studies between gene variants and intermediate and final CVD phenotypes. Replication of initial findings in various populations is now the most commonly used and demanded tool to demonstrate the validity of GWAs results. In addition, a number of meta-analyses are appearing that evaluate the effect of one or more genetic variants on the final and intermediate phenotypes of CVD. The recently published meta-analyses on the effects of the classic APOE and CETP polymorphisms in plasma lipids and CVD risk (97,98) are some examples of this trend. The first of these (97), included 86,067 individuals for the intermediate phenotypes and 37,850 cases and 82,727 controls for the disease phenotypes. The second of these (98), included 113,833 individuals for the intermediate phenotypes and 27,196 coronary cases and 55,338 controls for the final phenotypes. In both, it was concluded that there was a very consistent effect of each of the polymorphisms on plasma lipid concentrations (mainly HDL-C in the case of CETP, and LDL-C in the case of APOE). None of these meta-analyses evaluated possible gene-diet interactions, but both concluded that certain heterogeneity between the studies could be observed. Gene-diet interactions could be one of the causes of heterogeneity observed in the studies involving different populations. In this case, the same genotype may have different effects on intermediate phenotypes or clinical outcomes depending on dietary intakes.

Based on results from initial studies, there is support for the notion that APOE locus interacts with dietary saturated fat, increasing LDL-C concentrations as well as CVD risk, more in E4 carriers than in others (E2 and E3). However, the evidence level of this interaction in epidemiological studies is low (63, 90, 99). Likewise, experimental evidence from animal studies or from gene expression studies is mostly lacking. Therefore, despite the numerous studies carried out, there is currently insufficient epidemiological evidence available in order to be able to introduce a dietary recommendation on fat consumption based on the APOE genotype. Most of the disturbing heterogeneity in the results of those studies may have its origin in their low statistical power, the lack of accurate measurements of dietary fats, confusion by other gene variants, confusion by other components of the diet such as alcohol or antioxidants, and other selection or information biases. Until all these factors are adequately controlled it will not be possible to have more definitive conclusions about the presence or not of a gene-diet interaction between the APOE genotype and fat. Therefore, building enough evidence to make dietary recommendations related to total fat intake, types of fatty acids, or dietary patterns (i.e., Mediterranean diet) based on APOE genotypes will require new, properly designed and standardized studies that can be replicated in different populations. The very thought that we have so far been unable to establish a gene-diet interaction that began to be studied more than ten years is quite remarkable. A significant amount of the blame for this situation is attributable to publication fashions. Nowadays, we have reached the time in which much better designed studies can be undertaken to conclusively characterize those interactions that we have been pursuing since the early ‘90s, such as those related to the APOE genotype, dietary fat and LDL-C. However, it is also true that investigating that interaction is no longer attractive in terms of innovation, and researchers prefer to focus on the recently discovered gene variants that make their research work appear more novel and gives them a greater chance of being published in high impact journals. However, progress in nutrigenomics needs to come from researching novel gene variants, as well as from revisiting classic interactions in order to establish clearly and to adequate scientific evidence level whether those gene-diet interactions do occur and to establish their magnitude and relevance.

Similar situation exists for the CETP locus. Initial studies reported a statistically significant interaction between a CETP polymorphism and alcohol consumption in determining HDL-C concentrations and CVD risk. However, its current evidence level, as in the case of APOE-fat interaction, is very low. The first report was that of the Fumeron et al (82) in French males (608 myocardial infarction patients and 724 controls). In that study, the increasing HDL-C effect of the B2 allele was absent in subjects drinking < 25 g/d of alcohol but increased considerable with higher values of habitual alcohol consumption (interaction: P < 0.001). Accordingly, the risk of MI was lower in B2 subjects who had a high alcohol consumption level. Following this observation, there have been differing results published on that interaction (94, 100). Thus, the Framingham Study did not support such interaction (101) nor was confirmed by a meta-analysis of Boekholdt et al (102) in about 13,000 individuals.

The APOE locus has also been shown to have statistically significant interactions with habitual alcohol consumption in determining plasma LDL-C (65) and HDL-C (103). Although consistency in studies has not been obtained, there is some evidence showing that moderate habitual consumption of alcohol could be beneficial for E2 carriers by significantly reducing their LDL-C plasma concentrations (65). However, for E4 carriers, alcohol consumption could be harmful for two reasons. First, alcohol drinking raises their LDL-C concentrations, and second, the expected HDL-C raising effect of alcohol is not seen in E4 carriers (103).

Similarly, a statistically significant gene-diet interaction has been published for the CETP locus and habitual dietary fat intake in determining HDL-C (104). However, there are hardly any studies that have later examined these interactions and the single one that has done so, did not replicate the findings (105).

Taking into consideration the significant contributions of these candidate genes to the variability in lipid levels it will be highly important to revisit these interactions using more powerful approaches than those available during the last two decades, in addition to continue the exploration of newly discovered genes, that generally have less impact over the variability of the lipid traits at the population level.

Gene-diet interactions that do not mask the genetic associations

An example of a gene-diet interaction that modulates the effects of a genetic polymorphism on an intermediate CVD phenotype while maintaining a statistically significant association between the SNP and the phenotype, is the case of the interaction between the –1131T>C SNP in the APOA5 gene promoter and PUFA intake (106). This SNP has generally being associated with greater triglyceride concentrations in carriers of the C allele. In the Framingham study, the significant association between the –1131T>C SNP and fasting triglyceride concentrations was observed in the population as a whole. However, when we examined the potential contribution of the habitual dietary intake on the modulation of that association, we found a statistically significant interaction between this SNP and PUFA intake. We dichotomized dietary PUFA according to the population mean (approx 6%). After multivariate control for potential confounders, we found a statistically significant interaction (P<0.001) between SNP –1131T>C and PUFA intake (>6% or <6% of energy) on triglyceride concentration. In the adjusted model, the –1131C allele was associated with an increase in fasting triglycerides (21%, P=0.002) only in subjects consuming >6% of energy from PUFA. However, mean fasting triglyceride concentrations were similar in carriers of the –1131C allele and TT homozygotes when PUFA consumption was low (P=0.600). We observed similar and significant interactions between PUFA consumption and SNP –1131T>C on remnant-like particles (RLP)-triglycerides (P<0.001) and RLP-cholesterol (P<0.001). As observed for fasting triglycerides, RLP-triglycerides concentrations were higher (34%, P=0.005) in subjects carrying the –1131C allele when they consumed more than 6% of energy from PUFAs. More in depth analyses of the dietary data brought up the fact that only omega-6, but not omega-3 PUFAs were associated with statistically significant increases of triglycerides in C-allele carriers.

A more recent example of how a gene-diet interaction can also be present, despite statistically significant effects being observed for the genotype-phenotype association, may be the case of TCF7L2 (transcription factor 7–like 2) gene. Genetic variation at this locus has consistently been associated with higher fasting glucose concentrations and higher diabetes risk in carriers of the variant allele (107). Despite that, recent studies have found an interaction between some of these variants and habitual dietary intake of carbohydrates in determining the above mentioned phenotypes (108, 109). Hence, in a case-control study carried out in the Nurses' Health Study (108), it was found that carbohydrate quality and quantity modified the risk of diabetes associated with TCF7L2 (rs12255372 G-to-T). Authors employed the dietary glycemic load (GL) as an indicator of both carbohydrate quality and quantity, and observed that the risk of diabetes associated with the TCF7L2 TT genotype was greater among individuals consuming a high-GL diet. Compared with the GG genotype, multivariate-adjusted ORs (95% CI) of diabetes associated with the TT genotype were 2.71 (1.64–4.47) among individuals in the highest tertile of GL. Corresponding OR among individuals in the lowest tertiles of GL was 1.66 (0.95–2.88). Similar results were obtained on considering the glycemic index. From these results, the authors concluded that the greater diabetes risk attributable to the TCF7L2 T variant was magnified under conditions of increased insulin demand. Despite the potential preventive interest that this gene-diet interaction could have, more studies to replicate that interaction are required before applying these results to clinical practice. This need is supported by the fact that another study reported in the EPIC-Potsdam Cohort (109) has also found a statistically significant gene-diet interaction between the rs7903146 C-to-T (in high LD with the rs12255372 G-to-T ) in the TCF7L2 gene and habitual whole-grain intake in determining diabetes risk; however, the results apparently contradict the findings of Cornelis et al (108). In the EPIC Potsdam Cohort, the carriers of the TCF7L2 variant allele do not present the protective effect of whole grain intake in diabetes risk, which in this case was observed in CC homozygotes.

Once these issues are resolved the knowledge of gene-diet interactions in cardiovascular genomics could be used to correct altered phenotypes (high fasting glucose and high triglycerides, among others), that are associated with a certain genotype. This could in the near future be included in guidelines and recommendations for clinical practice for those patients with genetic susceptibility and inappropriate dietary behavior. However, as we have reiterated throughout this review, it is essential to increase their level of consistency and scientific evidence by means of further studies.

Can gene-diet interactions be responsible for lack of association between genetic variants and CVD intermediate or final phenotypes?

In the case of above mentioned polymorphisms (APOE, CETP, APOA5, TCF7L2), a genetic effect of their genotypes on plasma lipid concentrations (higher LDL-C concentrations in E4 allele carriers; higher HDL-C concentrations in B2 allele carriers; higher TG concentrations in –1131T>C APOA5 carriers and higher fasting glucose concentrations and diabetes risk in carriers of the variant allele in the TCF7L2 gene, all of these compared with homozygote subjects for the most common allele) has been widely described. In this situation, diet would act by slightly modulating the effect of these alleles, allowing us to observe genetics effects on a global level. Nevertheless, not all gene-diet interactions are of this type. Some of them may occur in situations in which a global genetic effect is not even observed. This would involve such a powerful gene-diet interaction that the environmental modulation would neutralize the genetic effects, giving rise to an observed null genetic effect in the population as a whole due to combination of different environmental exposures with opposite effects.

A classic example to illustrate this situation could be the common -75G>A APOA1 polymorphism and its association with HDL-C concentrations. In the Framingham Study (110), this polymorphism was not associated either with HDL-C concentrations in the population as a whole. However, in women, a statistically significant interaction was found with habitual PUFA intake as a continuous variable and APOA1 genotype (P = 0.005). Thus, when PUFA intake was low (<4% of energy), G/G subjects had higher HDL-C concentrations than did carriers of the A allele (P < 0.05). Conversely, when PUFA intake was high (>8% energy), HDL-C in carriers of the A allele were higher than those of G/G subjects (P < 0.05).

Another example of this situation is illustrated by the 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) locus, food intake and myocardial infarction (MI) (93) in a Costa Rican case-control study. In this case, a polymorphism in the 5-LO locus was not associated with MI in the population as a whole, but was differentially associated depending on the strata of food intake. The 5-LO pathway, which generates leukotrienes from arachidonic acid (AA), has drawn much attention for its role in CVD. 5-LO catalyzes the rate-limiting step of the biosynthesis of proinflammatory leukotrienes from AA and has been associated with atherosclerosis. It was hypothesized that a 5-LO promoter polymorphism consisting of tandem Sp1-binding sites could be associated with greater carotid atherosclerosis and then to higher risk of myocardial infarction. However, when the population as a whole (1885 cases and 1885 paired controls) was studied, no statistically significant association between the 5-LO promoter polymorphism and MI was found. However, when the amount of habitual dietary intake of AA was considered (low and high AA intake), a statistically significant gene-diet interaction was found. Thus, relative to the common 5 repeat promoter allele, the 3 and 4 alleles were associated with a higher MI risk in the high (≥0.25 g/d) dietary AA group (OR: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.07–1.61) and with a lower risk in the low (<0. 25 g/d) AA group (0.77; 0.63–0.94) (P for interaction = 0.015). These results support the hypothesis that the effect of the 5-LO promoter repeat polymorphism on higher atherosclerosis risk is exacerbated by high dietary AA but decreased by a low intake of AA.

Taking into account that gene-diet interactions can hide associations of certain genetic polymorphisms on intermediate or final CVD phenotypes, effort should be placed into the reanalysis of data for which no significant associations were found between specific genetic variants and CVD- related phenotypes. For example, most GWAs have not been considering the effects of dietary factors and they should be re-analyzed (if valid data on food intake is available) for genotype-phenotype associations using different nutrient/food component strata or dietary patterns. This should provide new associations between SNPs and an intermediate or final CVD phenotype which would depend on the amount or type of food consumed.

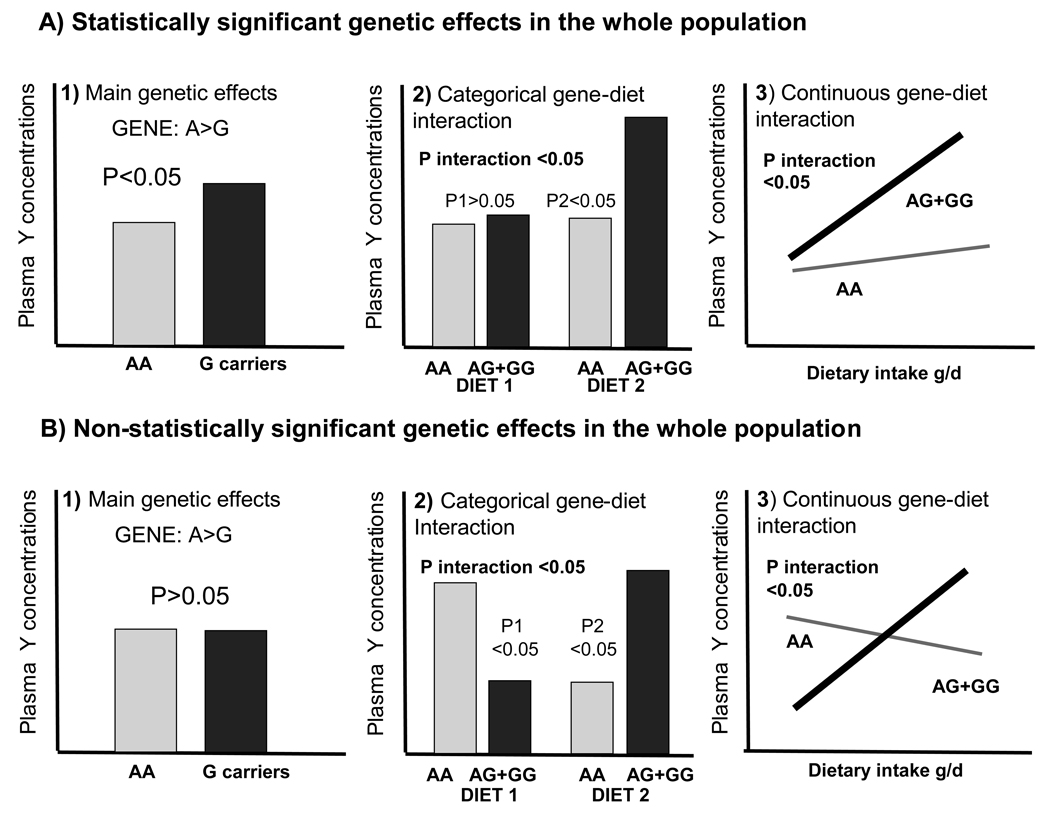

To illustrate the above mentioned points, Figure 1 shows two hypothetical situations resulting in significant gene-diet interactions. The first one (Figure 1A) is the most common, and has higher biological plausibility. In this case, a statistically significant association between the gene variant (A>G, as example) and the hypothetical phenotype analyzed (plasma Y concentration) can be seen in the whole population (A1). The presence of the gene-diet interaction (as categorical in A2, and as continuous in A3) makes the association between the genotype and phenotype stronger in one of the dietary intake strata, and weaker in the other to the point of losing statistical significance. In the second situation (Figure 1B), no genetic association is observed in the whole population (B1). Therefore, the SNP is not significantly associated with the phenotype. However, following stratification by the diet component that modulates the genetic effect in a dose-dependent way, an inverse genetic association can be seen for each of the diet strata (B2 and B3). There are also intermediate gene-diet interaction situations that have mixed characteristics between those depicted in Figures 1A and 1B.

Figure 1. Types of statistically significant gene-diet interactions.

Figure 1A. Statistically significant gene-diet interaction in which the genotypic effects are statistically significant in the whole population. Main genetic effects (A1), gene-diet interaction as categorical (A2) and as continuous (A3). P1 and P2 indicate the P values for mean comparison of the phenotypical trait (Plasma Y concentrations as example) depending on the genotype (A>G variation as example) in each of the dietary strata (diet 1 and diet 2) for the categorical variable. The gene-diet interaction makes that association between the genotype and phenotype stronger in one of the dietary intake strata, and weaker in the other. In the second situation (Figure 1B), no genetic effect is observed in the whole population (B1). Presence of the gene-diet interaction was depicted as categorical (B2) and as continuous (B3). The SNP is not significantly associated with the phenotype, but if it is stratified by the diet component the inverse genetic effect in each of dietary strata can be statistically observed.

Some relevant gene-diet interactions may not be statistically significant

Despite current interest for gene-diet interactions, the essential issue of defining and detecting gene-diet interactions remains vague, and the concept of gene-environment interactions is repeatedly used, but rarely specified with precision (111,112).

In recent years, published gene-diet interactions have largely focused on those that are statistically significant (113), meaning that statistical regression models including interaction terms are adjusted and the statistical significance of the interaction term between the dietary exposure and the corresponding genetic variable is estimated. If that interaction term is statistically significant (P<0.05), it is concluded that a gene-diet interaction exists. These interactions can include both continuous and categorical variables and predict both dichotomic and continuous outcomes (111–113). For example, statistical interaction exists if the degree or direction of the effect of one dietary factor (e.g., dietary fiber) differs according to values of a second factor (gene variants). In a simple gene-diet interaction model, in which both the susceptibility genotype at a single locus and the dietary exposure are considered dichotomous in predicting a dichotomous outcome (e.g., hypertension), one can fit a logistic regression model incorporating genetic and environmental factors in studying the risk of disease. The statistical interaction of these two factors can be measured as a departure from a multiplicative regression model of disease risk.

In addition, it is common to predict continuous variables, such as blood pressure, BMI, fasting glucose, plasma lipid concentrations, etc., as well as to analyze continuous variables to measure dietary intake. Then, covariance regression models with interaction terms are commonly employed. An example of this, are the situations that we mentioned above in Figure 1. Furthermore, it should also be borne in mind that, from a strict point of view, it is not clear what ultimately constitutes interaction or synergy on the biological level; any statistical approach is inherently arbitrary and model-dependent (111–115).

Moreover, we must be aware of the fact that, for their application in the clinical practice of cardiovascular medicine, we not only have to consider statistically significant gene-diet interactions, but also other gene-diet interactions for which the interaction term does not reach the statistical significance. Therefore, it is essential to reconsider the concept of gene-diet interaction and not to discard the potential use of other dietary modulations that could modify genetic susceptibility without the interaction term in the mathematical model being statistically significant. Generally speaking, by genetic determinism we mean that situation in which the genotype completely determines the phenotype, that is, the genes alone determine human traits (112, 116). Assuming then a pure genetic determinism, the intermediate and final CVD phenotypes would only be determined by genetic variability, without the environment being important. In this situation, if a subject had a genetic alteration, such genetic susceptibility would irreversibly determine the CVD phenotype, and that genetic influence would be totally independent of diet. Although it is not well quantified, this genetic determinism situation is thought to be very unusual, the normal situation being that of the modulation of phenotypes by environmental factors. Therefore, it is said that a biological gene-environment interaction situation takes place when there is an environmental factor capable of modifying genetic susceptibility. In other words, a biological gene-environment interaction occurs when a genetic risk factor leads to disorder only under certain environmental conditions or when adverse environmental conditions lead to disorder only for those individuals at genetic risk (112). This is not a new concept; it dates back at least to the beginning of the twentieth century, before the discovery of DNA. It was Sir Archibald Garrod who in a 1902 landmark paper suggested a genetic basis for differences in chemical metabolism and noted that these differences “will readily be masked by the influences of diet”. This concept of biological gene-environment interaction is independent of the statistical significance. In some cases, there are biological gene-environment interactions for which the interaction terms between diet and the genotype are not statistically significant; whereas for others a statistically significant interaction is detected.

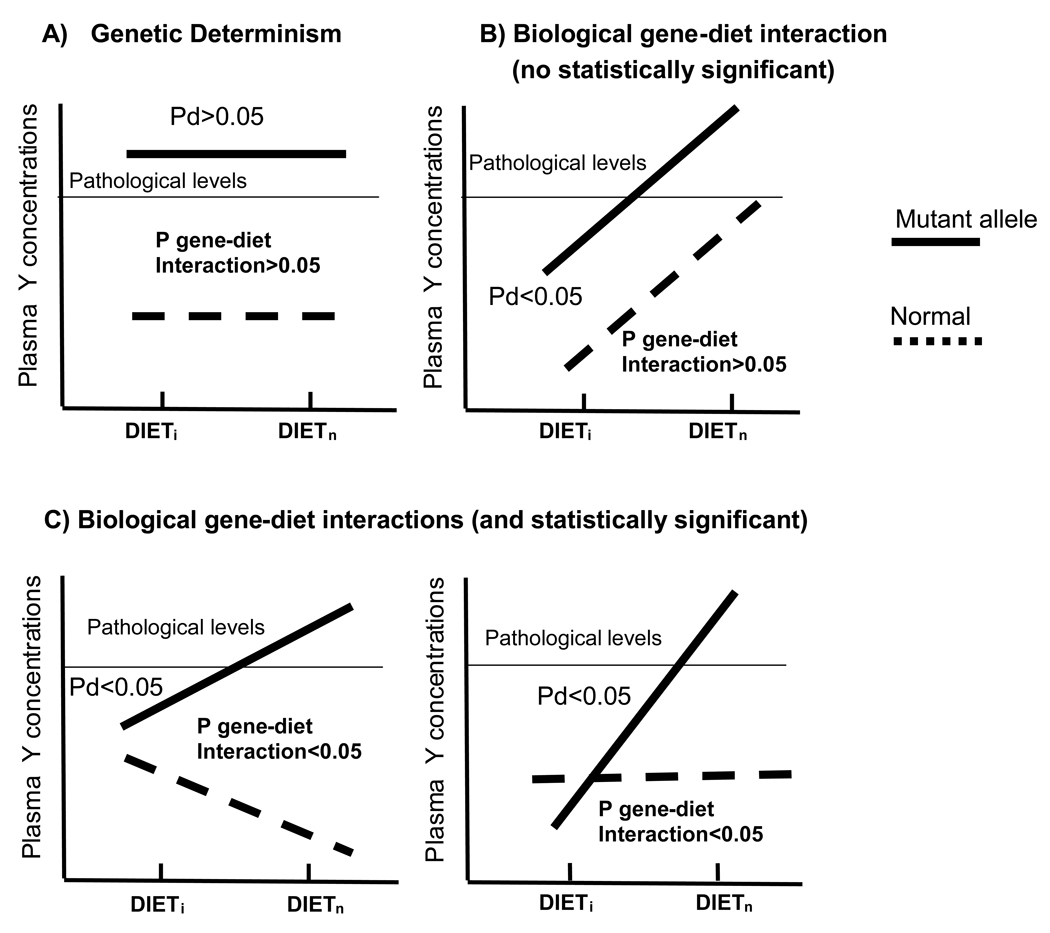

To better understand this, let us consider the genetic determinism and the biological gene-environment interaction scenarios (Figure 2). In figure 2A, subjects carrying the mutant allele have higher plasma concentrations of the “Y” parameter (always in the pathological level) than normal subjects, independently of the dietary intake. The P value for the dietary effect (Pd) in subjects carrying the mutant allele is not statistically significant. Figure 2B show a biological gene-diet interaction for which the P value for the gene-diet interaction term does not reach the statistical significance. However, depending on the diet, the plasma concentration of the Y parameter in subjects carrying the mutant allele is statistically different, ranging from non-pathological to pathological concentrations (Pd<0.05). Although the interaction term does not reach the statistical significance, statistical significant differences across dietary strata in genetically susceptible subjects must have to be demonstrated in biological interactions. Figure 2C shows two common situations of biological gene-diet interactions that also have statistically significant interaction terms between diet and the genotype.

Figure 2. Genetic determinism and biological gene-diet interactions.

A phenotypical trait (plasma Y concentrations) depending on the genotype (normal vs mutant allele) and diet (from dieti and dietn) according to: Genetic determinism (A), a biological but not statistically significant gene-diet interaction (B), and two common biological and statistically significant gene-diet interactions (C). P values for the interaction terms between genotype and diet as well as P values (Pd) for mean differences of the Y parameter in subjects carrying the mutant allele depending on the diet (Dieti and Dietn) are shown. Pathological levels of plasma Y concentrations are also indicated.

To use a more specific example, let’s think about a gene variant which is associated with higher LDL-C concentrations and subsequent greater risk of MI. However, this situation is not deterministic and can be modulated by the intake of dietary saturated fat, in such a way that a low saturated fat intake would neutralize the genetic effect in the subjects carrying the mutant allele (P<0.05), by preventing the increase of their LDL-C concentrations, thus reducing the risk of subsequent MI. This gene-diet interaction does not necessarily have to reach statistically significance, as a lower fat intake can also simultaneously reduce LDL-C concentrations in individuals without the risk genotype. This interaction is a “biological interaction”. It is important to identify biological interactions because doing so provides opportunities for the prevention and treatment of phenotypic alterations in people who are in a situation of greater risk due to their genotype. That is to say, in this case a lower saturated fat intake would reduce LDL-C concentrations both in subjects with the risk gene variant and in those without. However, nutritional education and motivation efforts for a low-fat intake could focus more on those persons in whom there is a greater risk due to the genotype.

Therefore, biological interaction exists when two or more factors influence a phenotype at the same time, but it does not necessarily entail a statistical interaction. Statistical interaction concerns the modeling of combined effects of two or more risk factors for a disease.

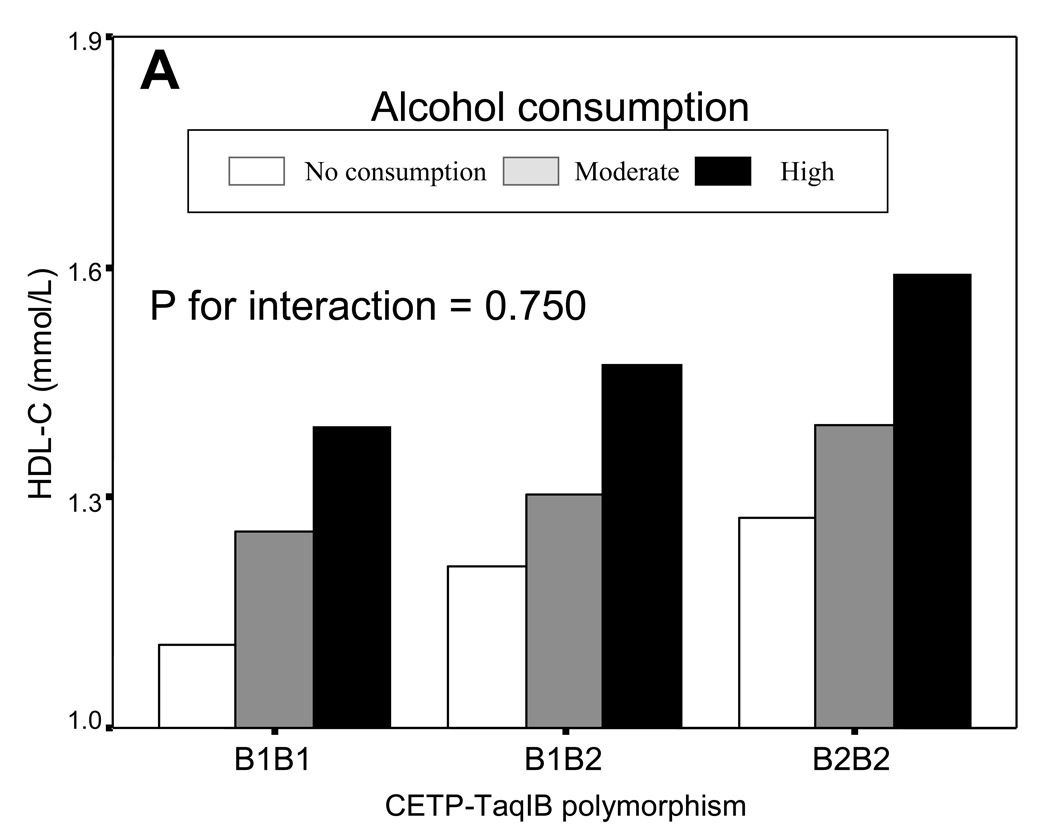

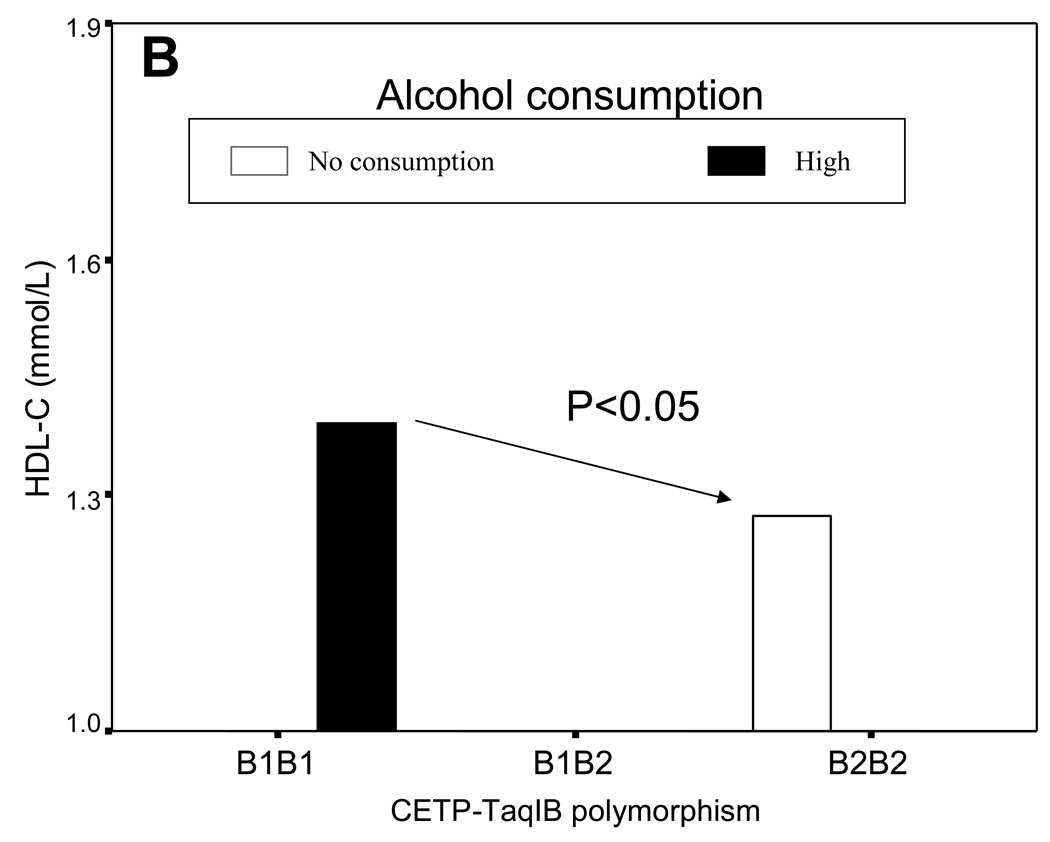

To better understand this concept; let us illustrate it with two real examples of biological and non-statistically significant gene-diet interaction. The first of these involves the CETP-TaqIB polymorphism and alcohol consumption determining plasma HDL-C concentrations (Figure 3). In the Framingham study, we observed that B1B1 individuals had lower HDL-C concentrations compared with B1B2 and B2B2 individuals (102). Later we investigated whether there was a gene-diet interaction of this SNP with alcohol consumption (102). Three categories of alcohol intake were considered according to reported daily intake: no alcohol intake, moderate, and high intake. No statistically significant interaction between the CETP-TaqIB genotype and alcohol intake was found (P=0.7) (33). However, as depicted in Figure 3A, a biological gene-diet interaction can be observed. If genetically the B1B1 subjects are predisposed to having lower HDL-C and this fact implies that they may present higher CVD risk, we would have to ask if there were some environmental factor (in this case diet) that could make the HDL-C concentrations in B1B1 subjects increase. Figure 3B displays the data for B1B1 extracted from Figure 3A and we can clearly see that there is no genetic determinism in the association between the CETP-TaqIB SNP and HDL-C concentrations. B1B1 subjects do not always have lower HDL-C concentrations than the other genotypes (genetic effect). Their HDL-C concentrations depends on alcohol consumption (just as in the other genotypes, hence there is no statistically significant gene-diet interaction). In accordance with Figure 3B, B1B1 subjects with high alcohol consumption present a statistically significant higher HDL-C (P<0.05) that B2B2 subjects who did not consume alcohol. Therefore, in a special situation of low HDL-C in B1B1 subjects, their HDL-C concentrations could be increased by alcohol consumption. This example has been included only to illustrate the biological interaction concept and we have to be very careful with recommendations on alcohol consumption in CVD prevention as the harmful effects of that consumption must not be overlooked.

Figure 3. Example of a biological, non-statistically significant, gene-diet interaction.

Plasma HDL-C concentrations depending on the CETP-TaqIB SNP and alcohol intake (3 categories: no alcohol intake, moderate, and high intake). No statistically significant gene-diet interaction is found (P for interaction between the CETP-TaqIB polymorphisms and alcohol consumption=0.750) (A). B: HDL-C concentrations in B1B1 subjects in the stratum of high alcohol consumption and HDL-C concentrations in B2B2 subjects in the stratum of no alcohol intake. P value for the comparison of means between B1B1 and B2B2 subjects.

The second example of a biological gene-diet interaction with no statistically significant interaction term, involves a -765G>C polymorphism in the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) gene, a Mediterranean diet intervention and serum concentrations of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) (117). The -765G>C COX-2 polymorphism was significantly associated with higher IL-6 and ICAM-1 concentrations in GG individuals. A Mediterranean diet intervention, significantly decreased IL-6 and ICAM-1 concentrations in both genotypes (effect independent from the genotype status that results in a no statistically significant gene-diet interaction). Following the dietary intervention with a Mediterranean diet, the GG individuals had IL-6 and ICAM-1 concentrations similar to C carriers before the intervention, so reducing the altered inflammation markers associated with genetic susceptibility. Therefore, a Mediterranean diet may overcome the risk status imposed by genetics.

Biological mechanisms underlying gene-diet interactions

Although remarkable progress has been made in identifying gene-diet interactions in epidemiological studies, the search of biological mechanisms underlying gene-diet interactions represents a major challenge. It is generally accepted that cellular processes spanning from gene expression to protein synthesis and degradation can be regulated by dietary components; however, there is a very limited understanding of the nutrient and non-nutrient-related networks. As Panagiotou et al outlined in their review on nutritional systems biology (118), a more complete knowledge of network function will further enhance our abilities to study the biological mechanisms underlying the observed differences in response to diet in genetically diverse individuals. In their review, they discuss the way to face and overcome the complexity of nutritional research using appropriate models system as well as the recent advances in the different x-omics applied to nutritional genomics, in particular nutritranscriptomics, nutriproteomics, nutrimetabolomics and nutritional systems biology, providing some interesting examples. Another review regarding the state-of-the-art and future applications of pathway mapping to the study of CVD is that published by Kanoni et al (119) discussing results from the KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathways “Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids” and “Sphingolipid metabolism” evidencing multiple changes in gene/lipid levels between low and high cholesterol treatment.

Applications of Nutrigenomics to the prevention and treatment of CVD

At present, it is premature to recommend the use of Nutrigenomics in the prevention of CVD at the population level. Most probably, the first applications of Nutrigenomics in cardiovascular medicine will involve normalization of altered intermediate CVD phenotypes, involving information about statistically significant as well as biological gene-diet interactions. Thus, it is essential to accumulate a series of well validated gene variants associated with CVD intermediate phenotypes in the whole population. This will facilitate the identification of genetically susceptible individuals on whom to carefully study dietary interventions aimed to successfully quench their genetic predisposition. In this process, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics in the context of systems biology will contribute to the elucidation of the molecular mechanisms involved in specific gene-diet interactions.

CVD and diet are both very complex and the most plausible scenario is that multiple genes will be used to create genetic profiles or scores (120). Consequently, attention should be paid to gene-gene interactions and to nutrient-nutrient interactions was well as to the classic gene-diet interaction (115–119). Biomedical informatics will help in tackling this complexity.

Whereas Nutrigenomics cannot be rigorously applied to cardiovascular prevention and treatment at this time, important results are being generated that will serve as the basis to increase the consistency of future research which, in turn, will achieve the necessary level of evidence. At that point, Nutrigenomics will become a reality in dietary personalization, in cardiovascular medicine, and subsequently in optimizing CVD treatment and prevention.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported by NHLBI grants U 01 HL72524 and HL-54776, NIDDK grant DK075030 and by contracts 53-K06-5-10 and 58-1950-9-001 from the US Department of Agriculture Research Service and by grants PI070954, CNIC06 and CIBER CB06/03/0035 from the ISCIII, Spain.

Footnotes

Journal Subject Codes: [89] Genetics of cardiovascular disease, [90] Lipid and lipoprotein metabolism, [109] Clinical genetics, [121] Primary prevention, [122] Secondary prevention, [143] Gene regulation.

Disclosures: None

REFERENCES

- 1.O'Donnell CJ, Nabel EG. Cardiovascular Genomics, Personalized Medicine, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Part I: The Beginning of an Era. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2008;1:51–57. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.813337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ioannidis. JPA. Prediction of Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes and Established Cardiovascular Risk Factors by Genome-Wide Association Markers. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:7–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.833392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding K, Kullo IJ. Genome-Wide Association Studies for Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease and Its Risk Factors. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:63–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.816751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hegele RA. Plasma lipoproteins: genetic influences and clinical implications. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:109–121. doi: 10.1038/nrg2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Govindaraju DR, Cupples LA, Kannel WB, O'Donnell CJ, Atwood LD, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Fox CS, Larson M, Levy D, Murabito J, Vasan RS, Splansky GL, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ. Genetics of the Framingham Heart Study population. Adv Genet. 2008;62:33–65. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(08)00602-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson PW. Assessing coronary heart disease risk with traditional and novel risk factors. Clin Cardiol. 2004;27(6 Suppl 3):III7–III11. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960271504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindner JR. Molecular imaging: Molecular imaging of cardiovascular disease with contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.77. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu FB, Willett WC. Optimal diets for prevention of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2002;288:2569–2578. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.20.2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mente A, de Koning L, Shannon HS, Anand SS. A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:659–669. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chahoud G, Aude YW, Mehta JL. Dietary recommendations in the prevention and treatment of coronary heart disease: do we have the ideal diet yet? Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:1260–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.07.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Horn L, McCoin M, Kris-Etherton PM, Burke F, Carson JA, Champagne CM, Karmally W, Sikand G. The evidence for dietary prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:287–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sievenpiper JL, Jenkins AL, Whitham DL, Vuksan V. Insulin resistance: concepts, controversies, and the role of nutrition. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2002;63:20–32. doi: 10.3148/63.1.2002.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gifford KD. Dietary fats, eating guides, and public policy: history, critique, and recommendations. Am J Med. 2002;113 Suppl 9B:89S–106S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00996-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hercberg S. The history of beta-carotene and cancers: from observational to intervention studies. What lessons can be drawn for future research on polyphenols? Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(1 Suppl):218S–222S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.218S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDonald BE. The Canadian experience: why Canada decided against an upper limit for cholesterol. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23(6 Suppl):616S–620S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dansinger ML, Gleason JA, Griffith JL, Selker HP, Schaefer EJ. Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2005;293:43–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAuley KA, Hopkins CM, Smith KJ, McLay RT, Williams SM, Taylor RW, Mann JI. Comparison of high-fat and high-protein diets with a high-carbohydrate diet in insulin-resistant obese women. Diabetologia. 2005;48:8–16. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1603-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Estruch R, Martínez-González MA, Corella D, Salas-Salvadó J, Ruiz-Gutiérrez V, Covas MI, Fiol M, Gómez-Gracia E, López-Sabater MC, Vinyoles E, Arós F, Conde M, Lahoz C, Lapetra J, Sáez G, Ros E PREDIMED Study Investigators. Effects of a Mediterranean-style diet on cardiovascular risk factors: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:1–11. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitfield-Brown L, Hamer O, Ellahi B, Burden S, Durrington P. An investigation to determine the nutritional adequacy and individuals experience of a very low fat diet used to treat type V hypertriglyceridaemia. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2009;22:232–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277x.2009.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howard BV, Van Horn L, Hsia J, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Kuller LH, LaCroix AZ, Langer RD, Lasser NL, Lewis CE, Limacher MC, Margolis KL, Mysiw WJ, Ockene JK, Parker LM, Perri MG, Phillips L, Prentice RL, Robbins J, Rossouw JE, Sarto GE, Schatz IJ, Snetselaar LG, Stevens VJ, Tinker LF, Trevisan M, Vitolins MZ, Anderson GL, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black HR, Brunner RL, Brzyski RG, Caan B, Chlebowski RT, Gass M, Granek I, Greenland P, Hays J, Heber D, Heiss G, Hendrix SL, Hubbell FA, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. JAMA. 2006;295:655–666. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jakobsen MU, O'Reilly EJ, Heitmann BL, Pereira MA, Bälter K, Fraser GE, Goldbourt U, Hallmans G, Knekt P, Liu S, Pietinen P, Spiegelman D, Stevens J, Virtamo J, Willett WC, Ascherio A. Major types of dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of 11 cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1425–1432. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown JM, Shelness GS, Rudel LL. Monounsaturated fatty acids and atherosclerosis: opposing views from epidemiology and experimental animal models. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2007;9:494–500. doi: 10.1007/s11883-007-0066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russo GL. Dietary n-6 and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: from biochemistry to clinical implications in cardiovascular prevention. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:937–946. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, Shahar DR, Witkow S, Greenberg I, Golan R, Fraser D, Bolotin A, Vardi H, Tangi-Rozental O, Zuk-Ramot R, Sarusi B, Brickner D, Schwartz Z, Sheiner E, Marko R, Katorza E, Thiery J, Fiedler GM, Blüher M, Stumvoll M, Stampfer MJ Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial (DIRECT) Group. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:229–241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sacks FM, Bray GA, Carey VJ, Smith SR, Ryan DH, Anton SD, McManus K, Champagne CM, Bishop LM, Laranjo N, Leboff MS, Rood JC, de Jonge L, Greenway FL, Loria CM, Obarzanek E, Williamson DA. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:859–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lovegrove JA, Gitau R. Personalized nutrition for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a future perspective. In: Lovegrove JA, Gitau R, editors. J Hum Nutr Diet. Vol. 21. 2008. pp. 306–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell BD, McArdle PF, Shen H, Rampersaud E, Pollin TI, Bielak LF, Jaquish C, Douglas JA, Roy-Gagnon MH, Sack P, Naglieri R, Hines S, Horenstein RB, Chang YP, Post W, Ryan KA, Brereton NH, Pakyz RE, Sorkin J, Damcott CM, O'Connell JR, Mangano C, Corretti M, Vogel R, Herzog W, Weir MR, Peyser PA, Shuldiner AR. The genetic response to short-term interventions affecting cardiovascular function: rationale and design of the Heredity and Phenotype Intervention (HAPI) Heart Study. Am Heart J. 2008;155:823–828. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lefevre M, Champagne CM, Tulley RT, Rood JC, Most MM. Individual variability in cardiovascular disease risk factor responses to low-fat and low-saturated-fat diets in men: body mass index, adiposity, and insulin resistance predict changes in LDL cholesterol. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:957–963. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.5.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keys A, Anderson JT, Grande F. Serum cholesterol response to changes in the diet. III. Differences among individuals. Metabolism. 1965;14:766–775. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(65)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abumrad NA. The gene-nutrient-gene loop. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2001;4:407–410. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200109000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ordovas JM, Corella D. Nutritional genomics. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2004;5:71–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.5.061903.180008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jansen AC, van Wissen S, Defesche JC, Kastelein JJ. Phenotypic variability in familial hypercholesterolaemia: an update. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:165–171. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200204000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corella D, Ordovas JM. Single nucleotide polymorphisms that influence lipid metabolism: Interaction with Dietary Factors. Annu Rev Nutr. 2005;25:341–390. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.25.050304.092656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hegele RA. Gene-environment interactions in atherosclerosis. Mol Cell Biochem. 1992;113:177–186. doi: 10.1007/BF00231537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ordovas JM, Lopez-Miranda J, Mata P, Perez-Jimenez F, Lichtenstein AH, Schaefer EJ. Gene-diet interaction in determining plasma lipid response to dietary intervention. Atherosclerosis. 1995;118:S11–S27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tall A, Welch C, Applebaum-Bowden D, Wassef M Report of an NHLBI working group. Interaction of diet and genes in atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:3326–3331. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.3326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pérusse L, Bouchard C. Gene-diet interactions in obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:1285S–1290S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.5.1285s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elliott R, Ong TJ. Nutritional genomics. BMJ. 2002;324:1438–1442. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7351.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]