Abstract

Cytochrome bc1 complex (EC 1.10.2.2, bc1), an essential component of the cellular respiratory chain and the photosynthetic apparatus in photosynthetic bacteria, has been identified as a promising target for new drugs and agricultural fungicides. X-ray diffraction structures of the free bc1 complex and its complexes with various inhibitors revealed that the phenyl group of Phe274 in the binding pocket exhibited significant conformational flexibility upon different inhibitors binding to optimize respective π-π interactions, whereas the side chains of other hydrophobic residues showed conformational stability. Therefore, in the present study, a strategy of optimizing the π-π interaction with conformationally flexible residues was proposed to design and discover new bc1 inhibitors with a higher potency. Eight new compounds were designed and synthesized, among which compound 5c with a Ki value of 570 pM was identified as the most promising drug or fungicide candidate, significantly more potent than the commercially available bc1 inhibitors including azoxystrobin (AZ), kresoxim-methyl (KM), and pyraclostrobin (PY). To our knowledge, this is the first bc1 inhibitor discovered from structure-based design with a potency of subnanomolar Ki value. For all of the compounds synthesized and assayed, the calculated binding free energies correlated reasonably well with the binding free energies derived from the experimental Ki values with a correlation coefficient of r2 = 0.89. The further inhibitory kinetics studies revealed that compound 5c is a non-competitive inhibitor with respect to substrate cytochrome c, but is a competitive inhibitor with respect to substrate ubiquinol. Due to its subnanomolar Ki potency and slow dissociation rate constant (k−0 = 0.00358 s−1), compound 5c could be used as a specific probe for further elucidation of the mechanism of bc1 function and as a new lead compound for future drug discovery.

Introduction

Understanding of the drug-receptor interactions is the molecular basis of designing new compounds with the higher potency.1 In fact, the interaction between drug and receptor is the interaction between the bioactive conformation of a drug molecule and the residues in the binding pocket of its receptor. A drug molecule will display the highest potency when its bioactive conformation matched very well with the binding pocket. Generally speaking, some residues in the binding pocket of a receptor protein might be conformationally flexible, while the others are rigid. Therefore, it should be an effective way to improve the potency of a drug by optimizing the interactions with the conformationally flexible residues in the binding pocket.

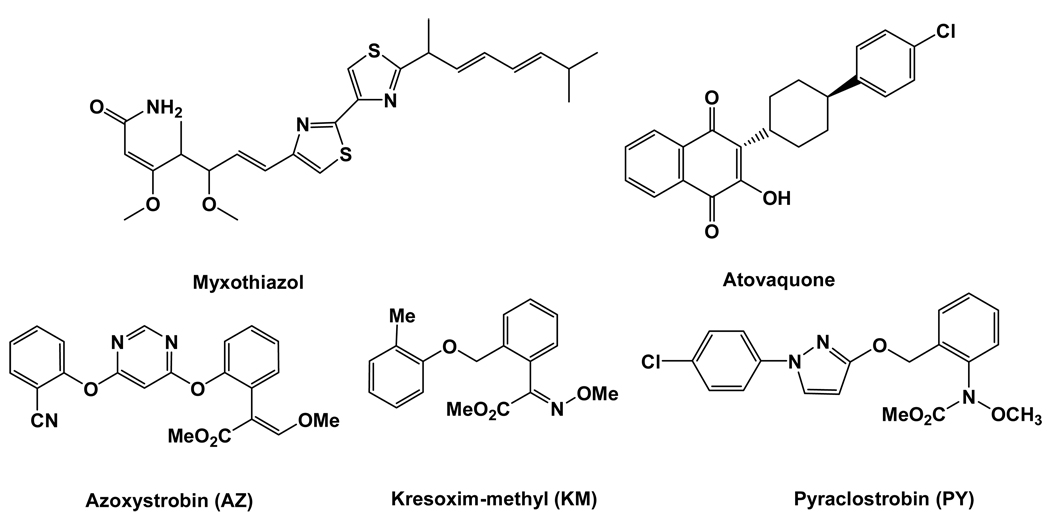

Cytochrome bc1 complex (EC 1.10.2.2, bc1) is well known as an essential component of the cellular respiratory chain and the photosynthetic apparatus in photosynthetic bacteria. Its function has been known to catalyze the electron transfer from quinol to a soluble cytochrome c (cyt c) and couple this electron transfer to the translocation of protons across the membrane.2–5 The bc1 complex has been found in the plasma membrane of bacteria and in the inner mitochondrial membrane of eukaryotes. Due to its crucial role in life cycle, the bc1 complex has been identified as a promising target for new drugs and agricultural fungicides.6,7 For example, malaria, especially chloroquine- and multidrug-resistant P. falciparum-malaria, remains a major threat to over 40% of the world’s population and is associated with about hundred million clinical cases every year. Atovaquone, as shown in Scheme 1, has been used in treating multidrug-resistant malaria and for prophylaxis in areas with chloroquine resistance for many years.8–12 The action mechanism of Atovaquone has been known to inhibit the bc1 complex by binding to the ubiquinol oxidation pocket of the bc1 complex, where it interacts with the Rieske iron-sulfur protein.11,12 In addition, a number of Qo-specific inhibitors of the bc1 complex, always named QoI fungicides, have been introduced into the agricultural fungicide market.13,14 The first QoI fungicides entered the market in 1996 include azoxystrobin (AZ) and kresoxim-methyl (KM) depicted in Scheme 1, two synthetic analogues of the natural antifugal compound strobilurin A. With a distributor sale value of over US$900 million apiece in 2008, AZ currently represents one of the most important fungicides in the world.

Scheme 1.

Chemical structures of some representative bc1 inhibitors

According to the structural information determined by the crystallographic studies, Xia et al.5 suggested that the existing bc1 inhibitors could be grouped into three classes: class P, class N, and class PN. Class P inhibitors binding at the Q0 site include famoxadone, stigmatellin, 5-undecyl-6-hydroxy-4,7-dioxobenzothiazole (UHDBT), methoxyacrylate-stilbene (MOAS), myxothiazol, AZ, KM, pyraclostrobin (PY), and many others. Class N inhibitors targeting the Qi site include antimycin A and diuron. Class PN inhibitors with the capability of binding to both the Q0 and Qi sites contain 2-n-nonyl-4-hydroxyquinoline N-oxide (NQNO) and possibly funiculosin. Among these inhibitors, MOA-type inhibitors, such as strobilurin, oudemansin and AZ, are very important due to their great commercial success and potential role in elucidating the molecular mechanism of bc1 function. However, these commercial inhibitors as agricultural fungicides or drugs are suffering from the rapid development of resistance associated with site mutations of bc1 complex. Therefore, discovery of new bc1 inhibitors with a higher potency is of great interest.15–17

X-ray diffraction structures of the free bc1 complex and its complexes with various MOA-type inhibitors revealed that the conformation of MOA moiety in the binding pocket is well conserved,3, 5 especially for the methoxy and carbonyl oxygen atoms, which makes it possible to identify common structural features that are important for binding. In addition, the Q0 pocket is hydrophobic and exceptionally rich in highly conserved residues (Supporting Information, Figure 1s). Most importantly, the Ar-Ar stacking interactions with the hydrophobic pocket formed by the side chains of Phe274, Phe128, Ile146, Pro270, Ala277, Leu294, Met124, and Ile298 (numbered according to the cyt b subunit of the bovine bc1) have an important contribution to the binding affinity of inhibitors.3, 5 It is noteworthy that the side chains of all these hydrophobic residues showed the conformational stability during the simulation, except that the phenyl group of Phe274 exhibited the significant conformational flexibility in different complexes. The conformational flexibility of Phe274 side chain allows to optimize the corresponding Ar-Ar interactions. However, due to the existence of the linear cyano group in AZ, the phenyl ring of the cyanophenoxyl group is almost vertical to the pyrimidyl ring. As a result, the pyrimidyl ring does not parallel well with the phenyl ring of Phe274 to reach an ideal Ar-Ar interaction. On the contrary, myxothiazol has higher potency than AZ because its thiazoles ring parallels well with the phenyl group of Phe274. These facts suggest that improving the Ar-Ar interactions between the side-chain of inhibitors and the phenyl of Phe274 may be an effective way to design and discover new, more potent inhibitors of bc1 complex.

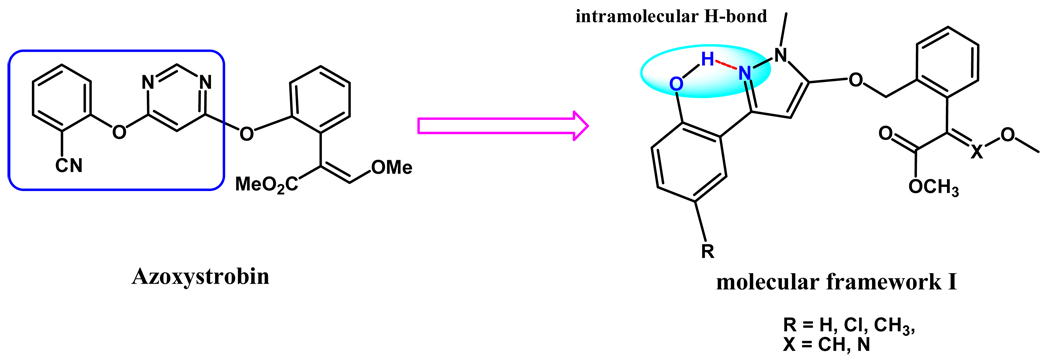

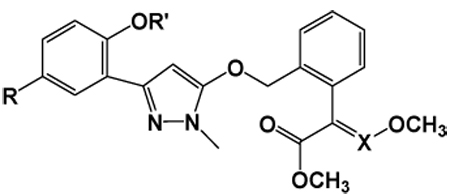

On the basis of the above premises, the development of new, more potent bc1 inhibitors by improving the Ar-Ar interactions of AZ is the main strategy of this work. Without altering the main structural features of MOA-type inhibitors, we first designed the molecular framework I (Scheme 2). As an important kind of five-membered aromatic scaffold with broad-spectrum biological activities, pyrazole ring has appeared in many of commercial drugs.18–20 Hence, we replaced the pyrimidine ring of AZ with a methylpyrazole ring as shown in Scheme 2. Meanwhile, an ortho-hydroxy group was designed to replace the cyano group with the expectation that an intramolecular hydrogen bond between the hydroxy group and the N(1) atom of pyrazole ring could be formed, which enables it possible for the pyrazole ring to perfectly parallel with the phenyl group of Phe274 to improve the Ar-Ar interactions. In addition, in order to adjust the hydrophobic property of the designed compounds, some functional groups, such as Cl and CH3, were also introduced into the R-position of the phenyl moiety.

Scheme 2.

Proposed structures of new bc1 inhibitors with an intramolecular hydrogen bond.

The strategy we proposed for the selection of compounds to be synthesized makes use of computational simulation protocols. These allow us to analyze the key interactions at the atomic level between the selected compounds and the bc1 complex. As a result, one compound with a Ki value of 570 pM against porcine bc1 complex was discovered. To our knowledge, it is so far the first bc1 inhibitor discovered through structure-based design with subnanomolar Ki potency. The synthesis, in vitro enzymatic assay, and subsequent enzymatic kinetic study are reported in this work. Its excellent potency and interesting characteristics of enzymatic kinetic behavior indicate that this compound could be used as a specific probe for further elucidating the mechanism of bc1 function and as a new lead compound for future drug discovery.

Materials and Methods

1. Computational methods

Homology Modeling of the Porcine Cytochrome b Subunit (cyt b)

In order to study the binding of a set of representative inhibitors with the porcine mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 complex, a homology model of the cyt b was built by using the complete crystal structure of bovine heart cytochrome bc1 in complex with AZ (PDB entry of 1SQB) as the template and the Homology module of InsightII program (version 2000, Accelrys, Inc., San Diego, CA). As one of the available cytochrome bc1 crystal structures containing inhibitors, the AZ-bound bc1 complex was selected as the template because of the structural similarity among the compounds used in this study. The sequence alignment between the porcine cyt b and the same subunit of the template was generated by ClusterW with the Blosum scoring function. The best alignment was selected according to both the alignment score and the reciprocal positions of the conserved residues, especially those in or close to the inhibitor-binding sites of the template. The coordinates of the conserved regions, including the two heme groups at bL and bH sites were transformed directly from the template structure, whereas the non-equivalent residues were mutated from the template to the corresponding ones in the porcine cyt b. The side chains of these non-conserved residues were relaxed by using the Homology module of InsightII program, in order to remove any possible steric overlap (or hinderance) with the neighboring conserved residues. The structures of other subunits of the porcine cyt bc1 complex were not modeled due to the shortage of their amino acid sequences of some of the subunits. For the purpose of viewing the structural integrity, the structures of other subunits of the porcine cyt bc1 complex were directly copied from the template providing their high homology to the bovine heart cyt bc1 complex.

After initial coordinates were generated, all the ionizable residues of cyt b were set to the standard protonation states. A careful check of the structural model allowed the proton to be assigned to the ND1 atoms for all the His residues under the physiological condition (pH = ~7.4), including His83, His97, His182, and His196 coordinated with the central irons of the two heme groups. As the His residues are coordinated optimally with the two heme groups as seen from the crystal structure, these residues and heme groups were always fixed in the following energy minimization steps. The initial 3D model of the porcine cyt b was energy-minimized by using the Sander module of the Amber8 program21 suite with a non-bonded cutoff of 12 Å and a conjugate gradient minimization method. The heme groups were treated at its oxidized state, and the input parameters of these heme groups were directly adopted from Izrailev et al.22 in their steered molecular dynamics simulations. The energy minimization was performed in the gas phase first for 5000 steps with the backbone atoms fixed, while the side chain atoms were relaxed, and then for another 1000 steps with the side chain atoms constrained in order to relax the backbone. After two rounds of these partial energy-minimization runs, the convergence criterion of 0.001 kcal mol−1 Å−1 was quickly achieved in a full energy minimization.

Molecular Docking

As observed from the crystal structure, AZ is bound in the Qo site which is formed by loop ef, helices cd1 and cd2, and part of the helices B, C, E, and F. Considering the structural similarity of AZ with other inhibitors, this Qo site was also selected as a binding site for other inhibitors. Based on the 3D model of the porcine cyt b, the AutoDock 4.0 program23 was applied to dock these inhibitors into the Qo binding site. The Gasteiger charges were used for these inhibitors. To select the best set of docking parameters and to test the reliability of the docking results, the AZ was first docked into the Qo binding site. In the docking process, conformational search was performed for AZ molecule using the Solis and Wets local search method, and the Lamarkian genetic algorithm (LGA) was applied for the conformational search of binding complex of AZ with porcine cyt b. Among a series of docking parameters, the grid size was set to be 40 × 40 × 40, and the used grid space was the default value of 0.375 Å. The interaction energy resulted from probing of the porcine cyt b with AZ molecule was assessed by the standard AutoDock scoring function. Among a set of 50 candidates of the docked complex structures, the best one was selected first according to the interaction energy, and was then compared with the conformation of AZ extracted from the crystal structure. By tuning the docking parameters, the final AZ-cyt b complex was obtained based on the smallest root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) of the docked conformation of AZ from its conformation in the crystal structure. The same set of docking parameters were adopted in the molecular docking of other inhibitors, including KM, PY, 5a~d, and 6a~d, into the Qo binding site of cyt b.

All the complex structures derived from molecular docking were used as starting structures for further energy minimizations using the Sander module of the Amber8 program before the final binding structures were achieved. The atomic charges used for these inhibitors were the restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) charges determined by using the standard RESP procedure implemented in the Antechamber module of the Amber8 program following the electronic structure and electrostatic potential calculations at the HF/6-31G* level. The energy minimization process was similar to that used for modeling the porcine cyt b, i.e. first fixing the backbone atoms of the protein, in order to relax the side chains and the docked inhibitor molecule. Then the energy minimization was performed on the whole complex until the convergence criterion of 0.001 kcal mol−1 Å−1 was reached.

Binding Energy Calculations

Due to the fact that only the structure of cyt b of the porcine bc1 complex was modeled, and due to the expected geometric symmetry of the dimer structure of the porcine bc1 complex, the binding free energy for each inhibitor with the porcine bc1 complex was represented by the binding free energy of each inhibitor with the cyt b. Such an approximation should be reasonable, as all the other subunits are far away from the Qo binding site and have no direct interactions with the inhibitors binding at the Qo site. Their effects on the inhibitor binding belong to the long-range interactions and, therefore, such long-range interactions can be treated as the background without significant influence on the calculated binding free energy (ΔGbind). Based on the modeled complex structure of porcine cyt b bound with inhibitors, the binding free energy for each of the minimized complexes was estimated by using the molecular mechanics-Possion-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) method.24

In the MM-PBSA calculations, the free energy of inhibitor binding, ΔGbind, was calculated from the difference between the free energies of the complex (Gcomplex), the free cyt b (Gcytb), and free inhibitor (Ginhibitor) as Eq.(1):

| (1) |

The ΔGbind was evaluated as a sum of the changes in the MM gas-phase binding energy (ΔEbind), solvation free energy (ΔGsolv), and entropy contribution (−TΔS).

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Electrostatic solvation free energy was calculated by the finite-difference solution to the Possion-Boltzmann (PB) equation (ΔGPB) as implemented in the Delphi program.25, 26 The dielectric constants used were 1 for the solute and 78.5 for the solvent. The SASA was calculated by the default surface area calculation program in the MM-PBSA module of Amber8 program with the default γ = 0.0072 kcal Å−2. The entropy contribution, −TΔS, to the binding free energy was calculated at T = 300 K by using an in-house program which has been used and proven to be reliable in our other studies.27–33

2. Syntheses of the title compounds

Unless noted otherwise, reagents and starting materials 1a~c were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purification whereas all solvents were redistilled before use. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Mercury-Plus 400 spectrometer in CDCl3 with TMS as the internal reference. MS spectra were determined using a Trace MS 2000 organic mass spectrometry. Elementary analyses were performed on a Vario EL III elemental analysis instrument. Melting points were taken on a Buchi B-545 melting point apparatus and uncorrected. Intermediates 2a~c, 3a~c, and 4a~b were prepared according to the reported methods.34–36

Preparation of 4-hydroxycoumarins (2a~c)

In a 250 mL two-neck round-bottom flask, 36 mmol o-hydroxyacetophenone 1 was added to 6.3 g of NaH (180 mol, 70%, dispersion in mineral oil) in anhydrous toluene (100 mL). After the evolution of hydrogen had ceased, 6 mL of diethyl carbonate in anhydrous toluene (20 mL) was dropwise added during 30 min, and the mixture was refluxed with stirring for 3 h. After cooling to room temperature, the precipitate was filtered off and washed with toluene 20 mL. The combined toluene solutions were concentrated on a rotary evaporator, and the residua was poured into 100 mL of water, and acided with 2N hydrochloric acid. The resulting precipitate was filtered off and recrystallized from ethanol to give white solid. Yields for 2a, 2b, and 2c are 85%, 72%, and 75%, respectively.

Preparation of 3-(2-hydroxy-5-substitutedphenyl)-1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-5(4H)-one (3a~c)

In a 100 mL three-neck round-bottom flask, 6 mmol of 6-substituted 4-hydroxycoumarins 2, 5.6 g (12 mmol) of methylhydrazine and 40 mL of ethanol were added gradually. The reaction was refluxed under N2 flow until the material was completely transformed by TLC. The resulting mixture was concentrated on a rotary evaporator to give the crude products. The white crystal 3 could be obtained by recrystallization of the crude products from ethanol. Yields for 3a, 3b, and 3c are 81%, 92%, and 90%, respectively.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Target Compounds (5a~d)

5.0 mmol of 3-(2-hydroxy-5- substitutedphenyl)-1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-5(4H)-one 3 and 0.82 g (6.0 mmol) of anhydrous K2CO3 in dry acetone (20 mL) was stirred and refluxed for 0.5 h, followed by the addition of 5.0 mmol of intermediate 4. The reaction was continued for 5–8 h under reflux. The resulting mixture was cooled to room temperature, filtered off by suction and the solvent was evaporated to give the crude product followed by chromatography purification on silica using a mixture of petroleum ether and acetone (12:1) as an eluent to give the target compounds 5a~d in yields of 67%~84%.

Data for 5a

Yield, 74%; M.p.129–131 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 3.69 (s, 3H, NCH3), 3.73 (s, 3H, COOCH3), 3.85 (s, 3H, =CH-OCH3), 5.07 (s, 2H, CH2), 5.82 (s, 1H, HetH), 6.87 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.99 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.15–7.23 (m, 3H, ArH), 7.38–7.43 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.53 (dd, J = 3.6 Hz, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.63 (s, 1H, =CH-OCH3). EI MS: m/z (%) 395 ([M+1]+, 17), 394 (M+, 100), 362 (19), 330 (14), 205 (60), 204 (42), 188 (13), 145 (83), 131 (23), 117 (38), 115 (25), 102 (51). Anal. Calcd for C22H22N2O5: C, 66.99; H, 5.62; N, 7.10. Found: C, 67.19; H, 5.38; N, 7.21.

Data for 5b

Yield, 84%; M.p. 143–145 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.29 (s, 3H, Ar-CH3), 3.68 (s, 3H, NCH3), 3.70 (s, 3H, COOCH3), 3.84 (s, 3H, =CH-OCH3), 5.06 (s, 2H, CH2), 5.81 (s, 1H, HetH), 6.88 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.98 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.20–7.24 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.37–7.41 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.52 (dd, J = 3.2 Hz, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.62 (s, 1H, =CH-OCH3). EI-MS: m/z (%) 409 ([M+1]+, 6), 408 (M+, 44), 205 (23), 204 (24), 175 (10), 146 (11), 145 (100), 131 (28), 103 (34). Anal. Calcd for C23H24N2O5: C, 67.63; H, 5.92; N, 6.86. Found: C, 67.36; H, 5.83; N, 6.90.

Data for 5c

Yield, 81%; M.p. 189–191 °C;1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ:3.68(s,3H,NCH3), 3.73 (s, 3H, COOCH3), 3.88 (s, 3H, =CH-OCH3), 5.06 (s, 2H, CH2), 5.73 (s, 1H, HetH), 6.88 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.08 (dd, J = 1.4 Hz, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.21 (dd, J = 3.6 Hz,J = 5.2 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.33 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.37 (dd, J = 3.2 Hz, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.50(dd, J = 3.6 Hz, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.64 (s, 1H, =CH-OCH3). EI-MS: m/z(%)428 (M+, 2), 204 (36), 189 (14), 160 (32), 144 (100), 128 (29), 115 (26), 101 (29), 91 (34).Anal. Calcd for C22H21ClN2O5: C, 61.61; H, 4.94; N, 6.53. Found: C, 61.35; H, 5.15; N, 6.59.

Data for 5d

Yield, 67%; M.p. 150–152 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ:3.66(s, 3H, NCH3), 3.86 (s, 3H, COOCH3), 4.08(s, 3H, =N-OCH3), 5.07 (s, 2H, CH2), 5.82 (s, 1H,HetH), 6.86 (t,J = 4.4 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.98 (d,J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.15–7.25 (m, 2H, ArH),7.40–7.54 (m, 4H, ArH),. EI MS: m/z (%) 395 (M+,42), 206 (10), 205 (20), 189 (28), 160 (41), 146 (31),131(96), 118 (37), 116 (100), 115 (19),89(27). Anal. Calcd for C21H21N3O5: C, 63.79; H, 5.35; N, 10.63. Found: C, 63.52; H, 5.58; N, 10.44.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Target Compounds (6)

A reaction system with 1.0 mmol of compounds 5a~b and 0.16 g (1.2 mmol) of anhydrous K2CO3 or 0.12 g (1.2 mmol) of triethylamine in dry N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) (6 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 0.5 h, followed by the addition of 1.1 mmol of halogenated compounds or substituted benzoyl chloride. The reaction was continued for 2–24 h. The resulting mixture was poured into 20 mL of water, extracted with ethyl acetate (10 mL×3), washed with saturated sodium chloride (10 mL×3), dried with anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered off with suction and the solvent was evaporated to give the crude, purified by chromatography on silica using a mixture of petroleum ether and acetone (20:1) as an eluent to give the target compounds 6a~d in yields of 46–82%.

Data for 6a

Yield, 78%; M.p. 117–119 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 3.68 (s, 3H, NCH3), 3.70 (s, 3H, COOCH3), 3.73 (s, 3H, =CH-OCH3), 3.86 (s, 3H, Ar-OCH3), 5.06 (s, 2H, CH2), 5.81 (s, 1H, HetH), 6.85 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.98 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.07 (dd, J = 3.6 Hz, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.16–7.24 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.38–7.42 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.54 (dd, J = 3.6 Hz, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.64 (s, 1H, =CH-OCH3). EI MS: m/z (%) 410 ([M+1]+, 3), 408 (M+, 2), 394 (100), 378 (10), 376 (31), 375 (83), 361 (17), 318 (13), 161 (16), 145 (26), 118 (21), 115 (14), 102 (29). Anal. Calcd for C23H24N2O5: C, 67.63; H, 5.92; N, 6.86. Found: C, 67.83; H, 6.01; N, 6.76.

Data for 6b

Yield, 46%; M.p. 152–153 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.32 (s, 3H, Ar-CH3), 3.70 (s, 3H, NCH3), 3.77 (s, 3H, COOCH3), 3.84 (s, 3H, =CH-OCH3), 3.87 (s, 3H, Ar-OCH3), 5.06 (s, 2H, CH2), 6.08 (s, 1H, HetH), 6.85 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.09 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.21 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.36–7.40 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.53 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.60 (s, 1H, =CH-OCH3), 7.71 (s, 1H, ArH). EI MS: m/z (%) 423 ([M+1]+, 8), 422 (M+, 9), 217 (13), 206 (18), 205 (91), 173 (14), 146 (13), 145 (100), 131 (19), 130 (20), 116 (24), 103 (12). Anal. Calcd for C24H26N2O5: C, 68.23; H, 6.20; N, 6.63. Found: C, 68.43; H, 5.99; N, 6.65.

Data for 6c

Yield, 82%; M.p. 83–85 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 3.65 (s, 3H, NCH3), 3.67 (s, 3H, COOCH3), 3.70 (s, 3H, =CH-OCH3), 4.91 (s, 2H, Ph-OCH2), 5.15 (s, 2H, Het-OCH2), 6.13 (s, 1H, HetH), 6.99–7.04 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.18 (dd, J = 4.0 Hz, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.31–7.39 (m, 6H, ArH), 7.43–7.48 (m, ArH), 7.51 (s, 1H, =CH-OCH3), 7.94 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, ArH). EI MS: m/z (%) 484 (M+, 9), 280 (13), 204 (100), 177 (21), 174 (14), 173 (23), 144 (98), 131 (32), 117 (16), 114 (54), 103 (37), 101 (35). Anal. Calcd for C29H28FN2O5: C, 71.88; H, 5.82; N, 5.78. Found: C,71.72; H, 5.62; N, 5.62.

Data for 6d

Yield, 81%; M.p. 76–77 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 3.61 (s, 3H, NCH3), 3.75 (s, 3H, COOCH3), 3.87 (s, 3H, =CH-OCH3), 5.39 (s, 2H, CH2), 5.76 (s, 1H, HetH), 7.11–7.19 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.28–7.33 (m, 3H, ArH), 7.34–7.40 (m, 3H, ArH), 7.61 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.69 (s, 1H, =CH-OCH3), 7.87 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.99 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 8.23 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, ArH). EI MS: m/z (%) 517 ([M+1]+, 6), 516 (M+, 8), 484 (20), 456 (24), 147 (14), 145 (43), 144 (23), 131 (17), 123 (100), 115 (22), 103 (23), 102 (14). Anal. Calcd for C29H25FN2O6: C, 67.43; H, 4.88; N, 5.42. Found: C, 67.15; H, 4.69; N, 5.12.

X-ray Diffraction

A colorless block of 5b (0.20 mm × 0.20 mm × 0.10 mm) was mounted on a quartz fiber. Cell dimensions and intensities were measured at 299 K on a Bruker SMART CCD area detector diffractometer with graphite mono-chromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å); θmax = 22.13; 6204 measured reflections; 3658 independent reflections (Rint = 0.0229) of which 2701 had |Fo| > 2|Fo|. Data were corrected for Lorentz and polarization effects and for absorption (Tmin = 0.9819; Tmax = 0.9909). The structure was solved by direct methods using SHELXS-97;37 all other calculations were performed with Bruker SAINT System and Bruker SMART programs.38 Full-matrix least-squares refinement based on F2 using the weight of 1/[σ2(Fo 2) + (0.0934P)2 + 0.1767P] gave final values of R = 0.0570, ωR = 0.1576, and GOF(F) = 1.055 for 289 variables and 1634 contributing reflections. Maximum shift/error = 0.000(3), max/min residual electron density = 0.209/−0.169 e Å−3. Hydrogen atoms were observed and refined with a fixed value of their isotropic displacement parameter.

3. Inhibitory Kinetics of Porcine bc1 Complex

The preparation of succinate-cytochrome c reductase (SCR, mixture of respiratory complex II and bc1 complex) from porcine heart was essentially as reported.39 The activity of SCR in catalyzing the oxidation of succinate by cytochrome c was determined in 1.8 mL of reaction mixture containing 100 mM PBS (pH 7.4), 0.3 mM EDTA, 20 mM succinate, 60 µM oxidized cytochrome c and an appropriate amount of SCR at 23°C. The enzymatic assay for succinate-ubiquinone reductase (complex II)-catalyzed oxidation of succinate by 2,6-dichloroindophenol (DCIP) was carried out in essentially the same reaction mixture, except the replacement of the oxidized cytochrome c with 53 µM DCIP. The reaction was initiated by the addition of enzyme, and monitored continuously by following the absorbance change at certain wavelength on a lambda 45 Perkin-Elmer spectrophotometer equipped with a magnetic stirrer. The extinction coefficients used were 18.5 mM−1cm−1 for for cytochrome c reduction and 21 mM−1cm−1 for for DCIP reduction. For the inhibitory kinetic studies, the reaction was carried out in the presence of varying concentration of the inhibitor.

The Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase (bc1 complex) activity in catalyzing the oxidation of decylubiquinol (DBH2) by cytochrome c was assayed in 100 mM PBS (pH 6.5), 2 mM EDTA, 750 µM lauryl maltoside (n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside), 20–115 µM DBH2, 100 µM oxidized cytochrome c, and an appropriate amount of SCR at 23°C. The preparation of DBH2 from decylubiquinone (DB) was carried out according to the procedure described in previous publications,40,41 and the concentration of DBH2 was determined by measuring the absorbance difference between 288 nm and 320 nm using an extinction coefficient of 4.14 mM−1cm−1 for the calculation.42,43 The nonionic detergent lauryl maltoside was used to decrease the interfering non-enzymatic activity,42–45 though it was expected to affect the Km value of DBH2 to bc1 complex.45 For each reaction, the non-enzymatic rate for cytochrome c reduction was followed for at least 100 seconds before enzyme was added to initiate the reaction.

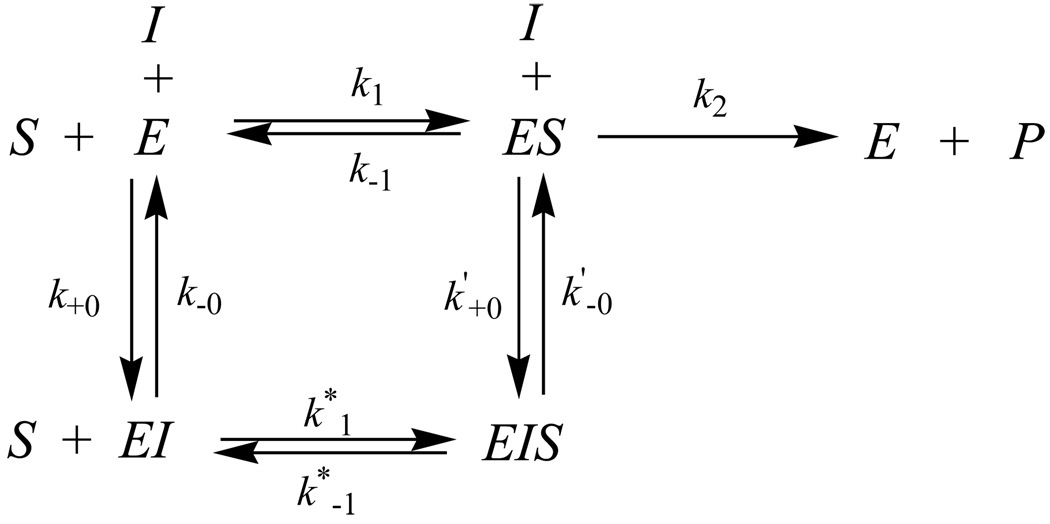

The reaction mechanism could be considered as follows (Scheme 3): where E, S, and I represent enzyme, substrate, and inhibitor, respectively. According to the substrate reaction kinetic theory, the concentration of product formed at time t is calculated by Eq.(6).46

| (6) |

where v0 and vs are the initial and steady-state velocities of the reaction in the presence of inhibitor, and kobs is the observed first-order rate constant:

We have Km and as the Michaelis-Menten constants:

Scheme 3.

The slow-tight binding inhibitors can also be classified as competitive, noncompetitive, and uncompetitive on the basis of similar considerations, as in the case of the classical inhibitors. Experimentally, the type of inhibition can be ascertained by studying the effect of [S] on the apparent rate constants A and B

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

Results and Discussion

Homology Modeling and Computational Prediction

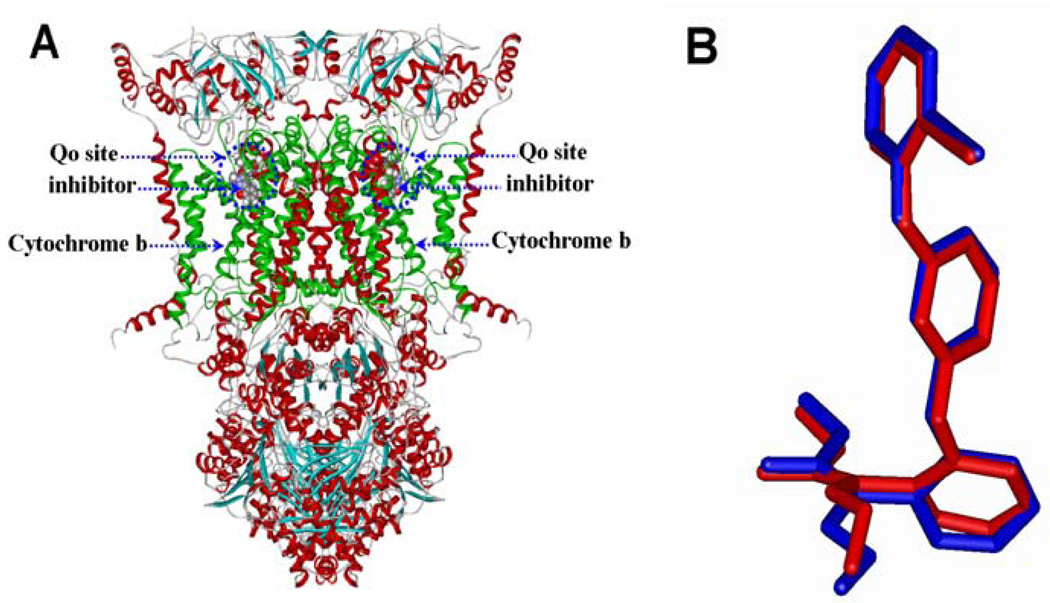

Because the Ki values of all compounds were tested based on the porcine bc1 complex in this work, we firstly used the crystal structure of bovine heart cytochrome bc1 in complex with AZ (PDB entry of 1SQB at resolution of 2.69Å) as a template to establish the three-dimensional (3D) structural model of porcine bc1 complex. The sequence alignment between the porcine cyt b and the same subunit of the template indicate that only 38 out of 379 residues were found to be different from each other, showing very high homology of the porcine cyt b with that of the template. The 3D structural models for procine bc1 in complex with inhibitors were simulated by integrating homology modeling, molecular docking, and energy minimizations as described in the experimental section. As shown in Figure 1A, the porcine bc1 complex is a dimmer and has the C2 symmetry. Each monomer contains one cyt b subunit in which the Qo site is situated. This Qo site is located near the inter-membrane space, and partially interacts with the bL heme group. The E-β-methoxy methyl acrylate group and the phenyl group of AZ are orientated at the deep bottom of the binding pocket. The E-β-methoxy methyl acrylate group interacts with residues Phe128, Tyr131, Val132, Gly142, and Ala143 from helix C and helix cd1, and residues Glu271 and Tyr 273 from the ef loop. This head group of the inhibitor blocks the way to the bL heme group with the shortest distances around 6 Å, while the distances of carbonyl oxygen atom of this head group of the inhibitor to the heme iron is about 10.5 Å. The carbonyl oxygen atom of this head group also forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone –NH group of residue Glu271 from the ef loop, further stabilizing the orientation of the head group of the inhibitor inside the Qo binding pocket. The phenyl group of the inhibitor packs residue Gly142, Val145, Ile146, Pro270, Ile268, and Tyr278 through extensive hydrophobic interactions. Compared with the conformation of AZ in the crystal structure (blue colored in Figure 1B), the rmsd for its docked conformation (red colored in Figure 1B) is only 0.77 Å. In addition, the calculated binding free energies for KM, AZ, and PY are in good agreement with the corresponding experimental data (Table 1, see below), indicating that our computational protocol is reliable.

Figure 1.

(A) The modeled 3D-structure of porcine bc1 complex with bound inhibitor. (B) Superimposition of the conformations of AZ in the crystal (blue) and modeled (red) structures.

Table 1.

Ki values of compounds 5, 6, KM, AZ, and PY against porcine bc1 complex

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | R | R’ | X | Ki (nM) | ΔG (kcal/mol) | Redisue Interaction Energies (kcal/mol) |

||

| ΔGcal.a | ΔGexp.b | F274 | P270 | |||||

| 5a | H | H | CH | 1.20 | −11.11 | −12.19 | −10.55 | −4.97 |

| 5b | CH3 | H | CH | 3.10 | −11.40 | −11.62 | −10.24 | −4.91 |

| 5c | Cl | H | CH | 0.57 | −12.50 | −12.63 | −10.28 | −4.86 |

| 5d | H | H | N | 3.80 | −10.17 | −11.50 | −10.49 | −4.88 |

| 6a | H | CH3 | CH | 29.10 | −9.08 | −10.29 | −10.30 | −4.95 |

| 6b | CH3 | CH3 | CH | 19.90 | −9.59 | −10.52 | −11.46 | −5.06 |

| 6c | H | C6H5CH2 | CH | 12.70 | −9.95 | −10.79 | −8.17 | −4.70 |

| 6d | H | p-FC6H4CO | CH | 97.70 | −9.09 | −9.56 | −8.57 | −4.95 |

| AZ | / | / | / | 297.60 | −8.57 | −8.92 | −9.48 | −4.53 |

| KM | / | / | / | 159.60 | −8.90 | −9.28 | −9.13 | −4.54 |

| PY | / | / | / | 3.30 | −10.95 | −11.59 | −7.92 | −6.23 |

ΔGcal. was calculated according to our modified MM-PBSA method.

ΔGexp. = −RTlnKi

Then, the above computational protocol was used to predict the potency of the designed compounds. The calculated binding free energies (ΔGcal.), summarized in Table 1, indicate that compounds 5a~d should have a significantly higher inhibitory potency than AZ and KM. In addition, compounds 5a, 5b, and 5d should have a similar inhibitory potency compared to PY, whereas compound 5c should have an inhibitory potency higher than PY. For an ideal computational protocol, it can be used to predict not only compounds with a higher activity, but also compounds with a lower activity. Therefore, in order to validate the predictability of the computational protocol, some hydroxy-protected compounds 6a~d were also predicted to have a lower potency due to the lack of the intramolecular hydrogen bond.

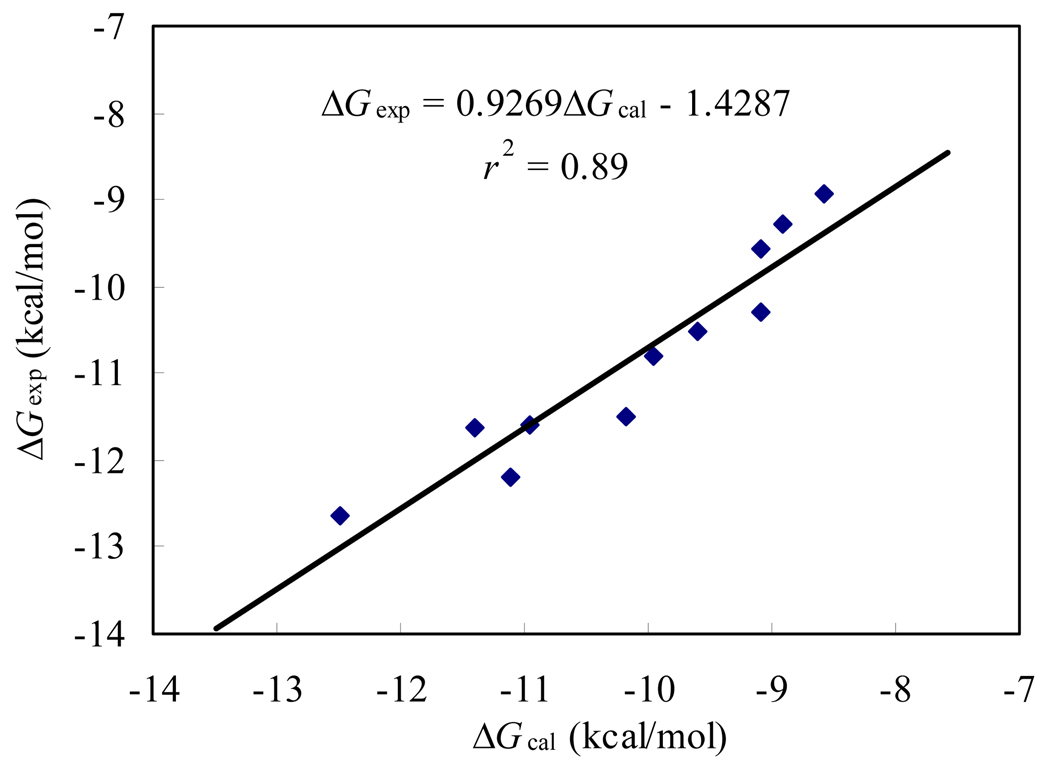

Table 1 also summarizes the Ki values against the porcine bc1 complex for the inhibition by the synthesized compounds and also by the commercial compounds that were used as the control. Interestingly, the calculated binding free energies correlated reasonably well with the binding free energies derived from the corresponding experimental Ki values with a correlation coefficient of r2 = 0.89 (Figure 2), further confirming the reliability of our computational models. As shown in Table 1, compound 5c distinguishes itself as the most promising candidate with the highest potency, with about 522-fold, 280-fold, and 5.8-fold improved binding affinity compared to AZ, KM, and PY, respectively.

Figure 2.

Correlation between the calculated and experimental binding free energies of compounds 5, 6, KM, AZ, and PY.

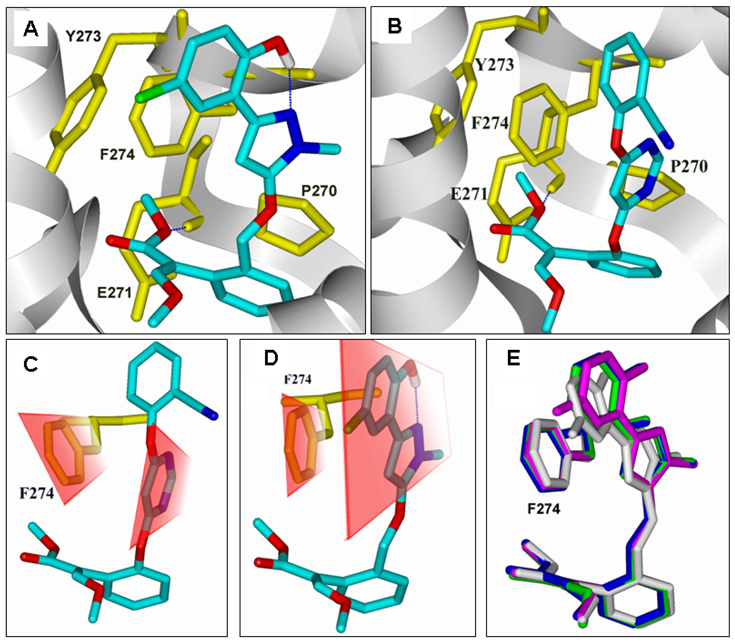

Structural Basis of the Higher Binding Affinity of Compounds 5a~d

As shown in Figure 3A and 3B, similar to that of AZ (Figure 3B), the methoxy methyl acrylate group of compounds 5a, 5b, 5c, and 5d form a hydrogen bond with the backbone amide group of Glu271 (Figure 3A and 3B). However, compared to that of AZ (Figure 3C), the π-π interactions between the Phe274 and the pyrazole ring of compound 5 are improved greatly because the pyrazole ring and the 2-hydroxyphenyl are totally coplanar due to the intramolecular hydrogen bond between the hydroxyl group and the N(1) atom of pyrazole moiety (Figure 3D). In other words, compared with the conformation in the AZ-complexed bc1, the phenyl side-chain of Phe274 undergoes a rotation of ~4° for in order to enhance the π-π interactions with compound 5c. Figure 3E shows the results of the superimposition of compounds 5a, 5b, 5c, and 5d based on the binding pocket. As a result, with about 522-fold, 280-fold, and 5.8-fold improvement of the binding affinity compared respectively with AZ, KM, and PY, compound 5c is clearly the most potent inhibitor. On the contrary, the hydroxy-protected derivatives, such as 6a, 6b, 6c, and 6d, all have a lower binding affinity due to the lack of such an intramolecular hydrogen bond.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the binding modes of compound 5c and AZ. (A), the simulated binding model of bc1 in complex with 5c; (B), the simulated binding model of bc1 in complex with AZ; (C), the π-π stacking interaction between the side chain of F274 and the pyrimidyl ring of AZ (the interaction energy between F274 and AZ is −9.48 kcal/mol); (D), the π-π stacking interaction between the side chain of F274 and the enlarged aromatic system of 5c (the interaction energy between F274 and 5c is −10.28 kcal/mol); (E) Superimposition of the binding-conformation of compounds 5a (green), 5b (white), 5c (magenta) and 5d (blue).

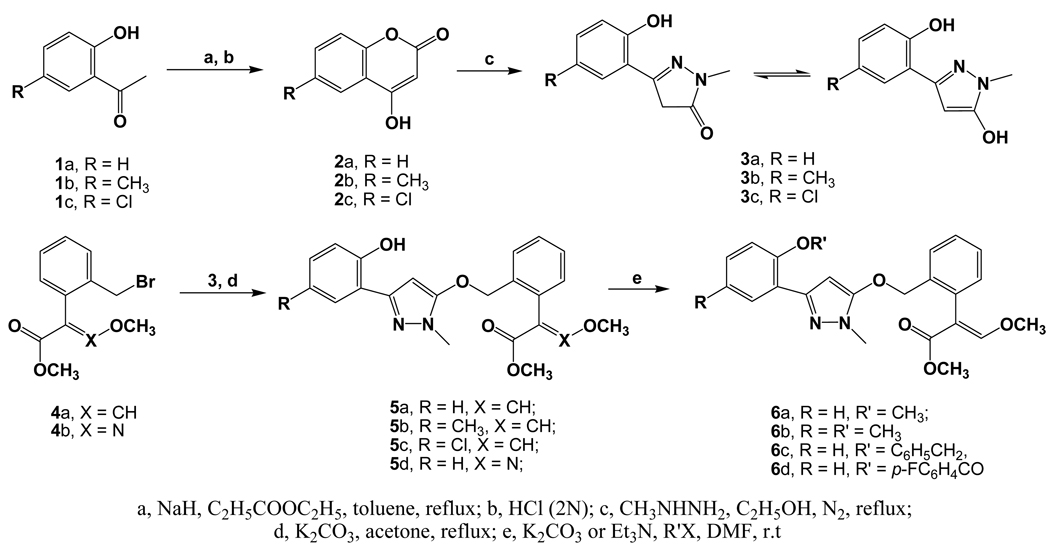

Synthesis of the Designed Compounds

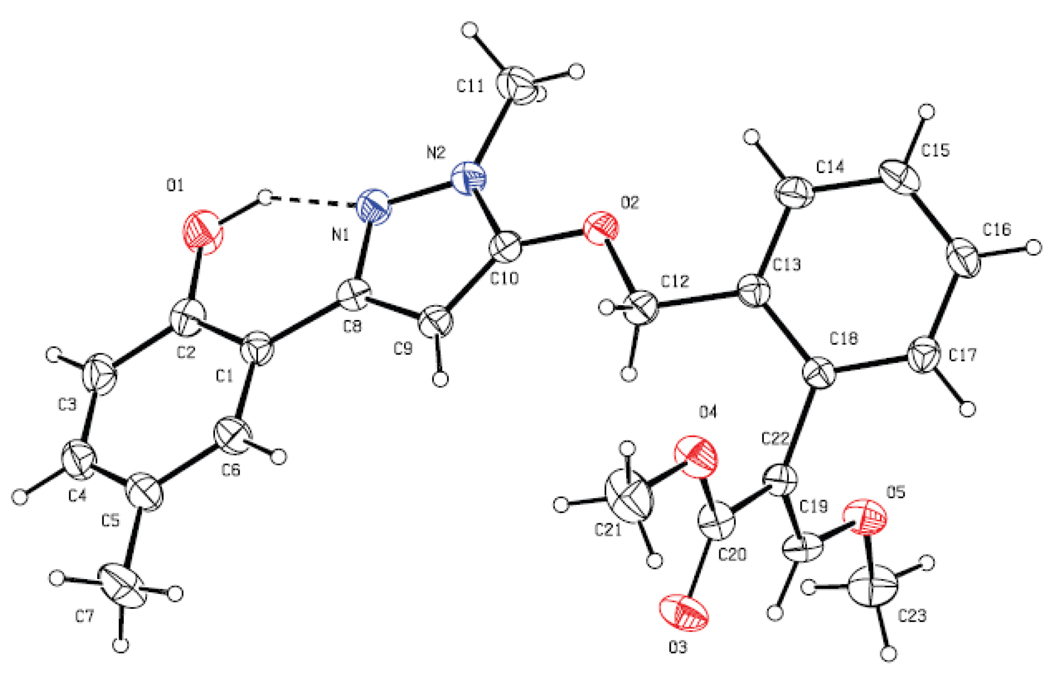

The synthetic route for the designed compounds 5 and 6 is shown in Scheme 4. 4-hydroxy-2H-chromen-2-one (also named 4-hydroxycoumarin) 2 was prepared easily from 2'-hydroxy acetophenone 1a~c as starting material in good overall yield (85% for 2a, 72% for 2b, and 75% for 2c). Then, compound 2 reacted with methylhydrazine to afford the key intermediate 3a~c, 3-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-5(4H)-ones. It should be noted that compound 3 underwent tautomerization under basic condition to produce the enol isomer. Fortunately, maybe due to the existence of intramolecular hydrogen bond, the resulted enol-hydroxy was apparently more active than the phenol-hydroxy group and reacted with (E)-methyl 2-(2-bromomethyl-phenyl)-3-methoxyacrylate 4 under the basic condition to produce the target compound 5 in yields of 67%~84%. In addition, in order to examine the importance of the intramolecular hydrogen bond, we also synthesized some hydroxy-protected compounds 6a~d by the reactions of compounds 5a and 5b with various alkylation or acetylation reagents. The structures of compounds 2~6 were characterized by 1H NMR, EI-MS spectrum, and elemental analyses. In addition, the crystal structure (CCDC 709734) of 5b was determined by X-ray diffraction analyses. As shown in Figure 4, the β-methoxyacrylate group adopts E-configuration. Most interestingly, an intramolecular hydrogen bond between the hydroxyl group and the N(1) atom was formed as expected. As a result, the pyrazole ring and the 2-hydroxyphenyl planes are coplanar to form a bigger aromatic system.

Scheme 4.

Figure 4.

Crystal structure of compound 5b (the dotted line shows the intramolecular H-bond)

Enzymatic Kinetics

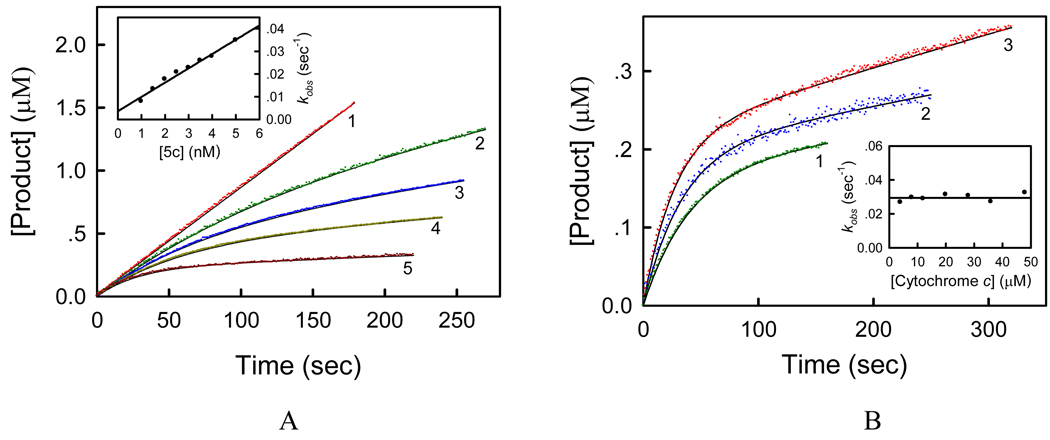

In order to understand the action mechanism, we further studied the inhibitory kinetics of succinate-cytochrome c reductase (SCR, mixture of respiratory complex II and bc1 complex) with compounds 5a–d. Complex II first passes electrons from succinate to ubiquinone, and then cytochrome bc1 complex passes electrons from reduced ubiquinone to cytochrome c. We measured the succinate-ubiquinone reductase (complex II) activity of SCR using succinate and DCIP as substrates and the succinate-cytochrome c reductase (both complex II and bc1 complex) activity of SCR using succinate and cytochrome c as substrates. All of the compounds exhibited no effect on the activity of complex II (data not shown), whereas they inhibited the activity of succinate-cytochrome c reductase considerably (Figure 5). Thus, the inhibition of these compounds on the activity of SCR may be attributed to their effects on the function of bc1 complex, and the assay for the SCR-catalyzed oxidation of succinate by cytochrome c was used to elucidate the inhibitory kinetics of the bc1 complex. Like many slow-binding inhibitors, the progress curves in the presence of compounds 5a–d did not display a simple linear product-versus-time relationship as seen for classical reversible inhibitors like AZ and KM. Rather, the product formation versus time shows a curvilinear function. For example, Figure 5A shows the time courses of the bc1 complex-catalyzed reaction in the presence of different concentrations of compound 5c. The progress curves start off linear (the initial-rate phase) but fall off with increasing time. When time (t) approaches the “infinity”, the concentration of product ([P]) approaches an asymptote with a positive slope, which decreases with increasing concentration of compound 5c. The initial-rate phase reflects the slow onset of inhibition by these compounds since it can be simply eliminated by preincubating the inhibitor with the enzyme (data not shown). Under the conditions employed in the present study, the time-dependent behavior of enzyme-catalyzed reaction can be well described according to the substrate reaction kinetic theory.46 The best-fit curves in Figure 5A were obtained by nonlinear regression analysis from which the kinetic parameters, the initial (v0) and steady-state (vs) velocities of the reaction in the presence of inhibitor and the observed first-order rate constant (kobs) can be determined. The inset of Figure 5A shows the plot of kobs against the concentration of compound 5c ([5c]). Noticeably, kobs is proportional to the inhibitor concentration. From the slope and intercept of this plot, the apparent rate constants A = 0.00631± 0.00036 s−1nM−1 and B = 0.00358 ± 0.00110 s−1 were then determined.

Figure 5.

(A) Inhibitory kinetics of bc1 complex by compound 5c. Each reaction mixture contains 100 mM PBS (pH 7.4), 0.3 mM EDTA, 20 mM succinate, 60 µM cytochrome c, 0.1 nM SCR, and certain amount of compound 5c (1, 0 nM; 2, 1 nM; 3, 1.5 nM; 4, 2 nM; and 5, 5 nM). Experimental data were shown as colored dots and theoretical values as black solid lines. Inset: plot of kobs against concentration of compound 5c. (B) Effect of cytochrome c concentration on the inhibition of bc1 complex by compound 5c. The assays were carried out in the presence of 5 nM compound 5c and various concentrations of cytochrome c (1, 4 µM; 2, 12 µM; and 3, 48 µM). Each reaction was initiated by adding 0.1 nM SCR. Inset: plot of kobs against concentration of cytochrome c.

Subsequently, we monitored the time courses of the bc1 complex-catalyzed reaction in the presence of different concentrations of cytochrome c and at a fixed concentration of compound 5c (Figure 5B). Using procedures described above, the values of kobs can be obtained by fitting the progress curves according to the substrate reaction kinetic theory and were plotted against the concentration of cytochrome c in the inset of Figure 5B. The data clearly revealed that kobs was independent of the concentration of substrate cytochrome c under the experimental conditions used, indicating that compound 5c is a non-competitive inhibitor with respect to cytochrome c. Thus, the values of A and B determined from Figure 5A are equal to the true association and dissociation rate constants k+0 and k−0, respectively, and the inhibition constant for compound 5c can be calculated as Ki = k−0 / k+0 = 0.57 ± 0.21 nM.

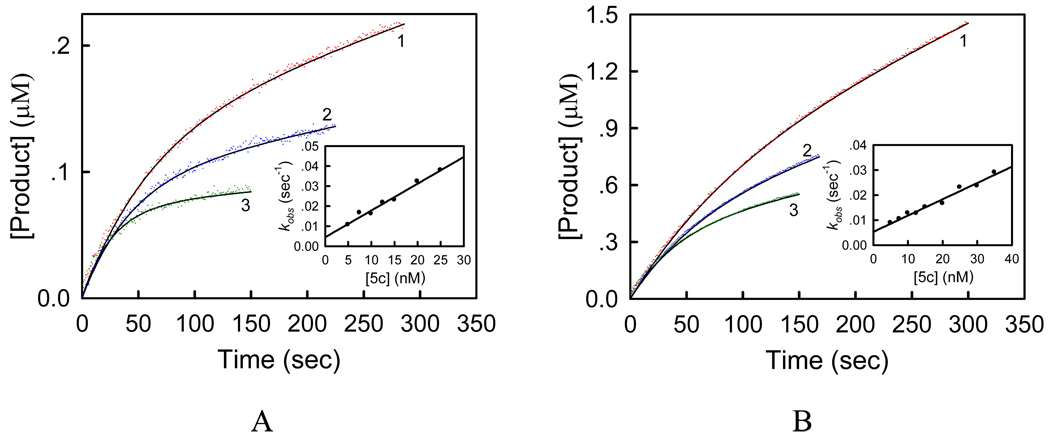

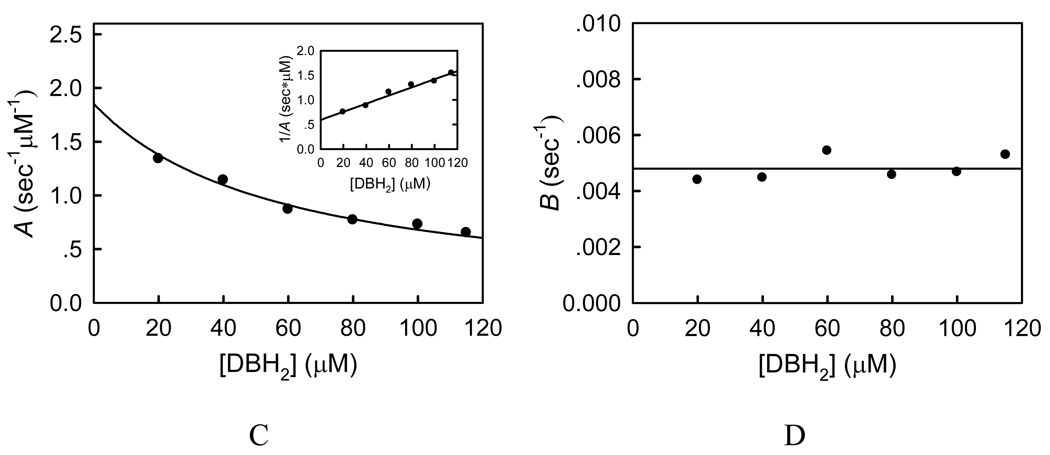

To study the effect of substrate ubiquinol on the inhibition kinetics of compound 5c, we directly measured the ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase (bc1 complex) activity of SCR using decylubiquinol (DBH2) and cytochrome c as substrates in the absence and presence of compound 5c. This reaction exhibited the Michaelis-Menten kinetics towards substrate DBH2, and the kinetic parameters were determined (Km = 58 ± 4 µM and kcat = 238 ± 8 s−1). In the presence of compound 5c, with succinate used as substrate, the progress curves exhibited a similar curvilinear pattern due to the slow onset of inhibition (Figure 6). However, when the experiments were performed at a fixed concentration of compound 5c, the kobs value decreased with increasing concentration of DBH2 (Supporting Information, Figure 2s), which is different from that observed in Figure 5B. To further elucidate the inhibitory mechanism, we carried out six sets of inhibitory experiments in the presence of varying concentrations of DBH2 and compound 5c (Figure 6, panels A and B). Similarly, from these progress curves of product formation at fixed concentrations of DBH2, the values of v0, vs, and kobs can be determined as described previously. Plot of kobs against the inhibitor concentration gives a straight line (insets of Figure 6A–B), from which the values of A (slope) and B (intercept) at indicated DBH2 concentrations were obtained. Panels C and D of Figure 6 show the dependence of the A and B values on the DBH2 concentration. Clearly, A deceased with increasing the concentration of DBH2, while B was not affected, suggesting that compound 5c is a competitive inhibitor with respect to substrate ubiquinol. Thus, with the Km value of 58 µM, the microscopic inhibition rate constants k+0 = 0.00185 ± 0.00003 s−1nM−1 and k−0 = 0.00480 ± 0.00018 s−1 can be obtained by fitting Eq.(2) to the experimental data, and the inhibition constant Ki = k−0/k+0 = 2.6 ± 0.1 nM can be derived. The Ki value determined is about 5-fold higher than that measured from the succinate-cytochrome c reductase activity inhibition, which is mainly due to the presence of lauryl maltoside. This nonionic detergent was reported to affect the Km value of DBH2 to bc1 complex,45 and it possibly has an impact on the microscopic inhibition rate constants and the Ki value. Indeed, we found that the kobs value decreased with increasing the concentration of lauryl maltoside at fixed DBH2 and compound 5c concentrations (Supporting Information, Figure 3s).

Figure 6.

(A–B) Inhibitory kinetics of porcine bc1 complex by compound 5c. Each reaction mixture contains 100 mM PBS (pH 6.5), 2 mM EDTA, 750 µM lauryl maltoside, 100 µM oxidized cytochrome c, 0.05 nM SCR, certain amount of DBH2 (A, 20 µM; B, 115 µM), and compound 5c (1, 7.5 nM; 2, 15 nM; 3, 25 nM). Experimental data were shown as colored dots and theoretical values as black solid lines. Insets: plots of kobs against concentration of compound 5c. (C) Plot of the apparent rate constant A against concentration of DBH2. Inset: plot of 1/A against concentration of DBH2. (D) Plot of the apparent rate constant B against concentration of DBH2.

Conclusion

In summary, we have successfully designed and synthesized a series of pyrazole derivatives as inhibitors of cytochrome bc1 complex. By introducing an intramolecular hydrogen bond to form a big aromatic system, the π-π interactions with the phenyl of Phe274, an important residue with conformational flexibility located in the binding pocket, were significantly improved. As a result, a new bc1 inhibitor with subnanomolar Ki potency was discovered. Compound 5c with a Ki value of 570 pM was found to display about 522-fold, 280-fold, and 5.8-fold improved binding affinity compared to the commercial inhibitors AZ, KM, and PY, respectively. The further inhibitory kinetics studies showed that compound 5c is a non-competitive inhibitor with respect to substrate cytochrome c, but a competitive inhibitor with respect to substrate ubiquinol. Due to its subnanomolar Ki potency and slow dissociation rate (k−0 = 0.00358 s−1), compound 5c could be used as a specific probe for further elucidating the mechanism of bc1 function and as a new lead compound for future drug discovery. In addition, the present work provides a successful case study concerning how to improve binding affinity of a ligand with a receptor by optimizing the interactions of the ligand with conformationally flexible residues of the receptor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research was supported in part by the National Basic Research Program of China (No. 2010CB126103), the NSFC (No. 20925206, 20932005, and 20872045), and the NIH (RC1MH088480). The authors also acknowledge Dr. Z. X. Wang for critical discussions and reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Complete citations of references 8 and 20. Figure 1s for Sequence alignment of the Q0 pocket residue. Figure 2s for Inhibitory kinetics of porcine bc1 complex by compound 5c, Figure 3s for effect of lauryl maltoside on kobs, Figure 4s for the enzyme kinetic of AZ. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Contributor Information

Chang-Guo Zhan, Email: zhan@uky.edu.

Jia-Wei Wu, Email: jiaweiwu@mail.tsinghua.edu.cn.

Guang-Fu Yang, Email: gfyang@mail.ccnu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Ladbury JE. Thermochim. Acta. 2001;380:209–215. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim H, Xia D, Yu CA, Xia JZ, Kachurin AM, Zhang L, Yu L, Deisenhofer J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:8026–8033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao XG, Wen XL, Yu GA, Esser L, Tsao S, Quinn B, Zhang L, Yu LD, Xia D. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11692–11702. doi: 10.1021/bi026252p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry EA, Huang LS. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esser L, Quinn B, Li YF, Zhang MQ, Elberry M, Yu LD, Yu CA, Xia D. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;341:281–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sauter H, Steglich W, Anke T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:1328–1349. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990517)38:10<1328::AID-ANIE1328>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiang H, McSurdy-Freed J, Moorthy GS, Hugger E, Bambal R, Han C, Ferrer S, Gargallo D, Davis CB. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006;95:2657–2672. doi: 10.1002/jps.20681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeates CL, et al. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:2845–2852. doi: 10.1021/jm0705760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fry M, Pudney M. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992;43:1545–1553. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kessl JJ, Meshnick SR, Trumpower BL. Trends Parasitol. 2007;23:494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mather MW, Darrouzet E, Valkova-Valchanova M, Cooley JW, McIntosh MT, Daldal F, Vaidya AB. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:27458–27465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502319200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessl JJ, Lange BB, Merbitz-Zahradnik T, Zwicker K, Hill P, Meunier B, Palsdottir H, Hunte C, Meshnick S, Trumpower BL. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:31312–31318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartlett DW, Clough JM, Godwin JR, Hall AA, Hamer M, Parr-Dobrzanski B. Pest Manag. Sci. 2002;58:649–662. doi: 10.1002/ps.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balba H. J. Environ. Sci. Heal. B. 2007;42:441–451. doi: 10.1080/03601230701316465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolgunas S, Clark DA, Hanna WS, Mauvais PA, Pember SO. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:4762–4766. doi: 10.1021/jm060408s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ding MG, Rago JP di, Trumpower BL. J. Bio. Chem. 2006;281:36036–36043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolesova GM, Belyakova MM, Mamedov MD, Yaguzhinsky LS. Biochemistry-Moscow. 2000;65:578–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonald E, Jones K, Brough PA, Drysdale MJ, Workman P. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2006;6:1193–1203. doi: 10.2174/156802606777812086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamberth C. Heterocycles. 2007;71:1467–1502. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansen J, et al. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:4692–4695. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearlman DA, Case DA, Caldwell JW, Ross WS, Cheatham TE, Debolt S, Ferguson D, Seibel G, Kollman P. Comp. Phys. Commun. 1995;91:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Izrailev S, Crofts AR, Berry EA, Schulten K. Biophys. J. 1999;77:1753–1768. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77022-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris GM, Goodsel DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, Olson AJ. J. Comput. Chem. 1998;19:1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kollman P, Massova I, Reyes C, Kuhn B, Huo S, Chong L, Lee M, Duan Y, Wang W, Donini O, Cieplak P, Srnivasan J, Case D, Cheatham TE. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:889–897. doi: 10.1021/ar000033j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jayaram B, Sharp KA, Honig B. Biopolymers. 1989;28:975–993. doi: 10.1002/bip.360280506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanner MF, Olson AJ, Spehner JC. Biopolymers. 1996;38:305–320. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199603)38:3%3C305::AID-BIP4%3E3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ji FQ, Niu CW, Chen CN, Chen Q, Yang GF, Xi Z, Zhan CG. ChemMedChem. 2008;3:1203–1206. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200800103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan YM, Gao DQ, Yang WC, Cho H, Yang GF, Tai HH, Zhan CG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:16656–16661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507332102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao DQ, Cho H, Yang WC, Pan YM, Yang GF, Tai HH, Zhan CG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:653–657. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan YM, Gao DQ, Yang WC, Cho H, Zhan CG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:13537–13543. doi: 10.1021/ja073724k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhan CG, Zheng F, Landry DW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:2462–2474. doi: 10.1021/ja020850+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiong Y, Li Y, He HW, Zhan CG. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:5186–5190. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.06.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan YM, Gao DQ, Zhan CG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5140–5149. doi: 10.1021/ja077972s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desai NJ, Suresh S. J. Org. Chem. 1957;22:388–390. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Froggett JA, Hockley MH, Titman RB. J. Chem. Res. (S) 1997:30–31. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim BT, Park NK, Choi GJ, Kim JC, Pak CS. WO 0112585. 2001 (Chem. Abstract 134, 193207) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheldrick GM. SHELXTL (Version 5.0) Germany: University of Gőttingen; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bruker . SMART V5.628, SAINT V6.45. & SADABS. Madison, Wisconsin, USA: Bruker AXS Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu L, Yu CA. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:2016–2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rieske JS. Methods Enzymol. 1967;10:239–245. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo C, Long J, Liu J. Clin Chim Acta. 2008;395:38–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fisher N, Bourges I, Hill P, Brasseur G, Meunier B. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271:1292–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fisher N, Brown AC, Sexton G, Cook A, Windass J, Meunier B. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271:2264–2271. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fisher N, Meunier B. Pest Manag Sci. 2005;61:973–978. doi: 10.1002/ps.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chretien D, Slama A, Brière J, Munnich A, Rötig A, Rustin P. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:233–239. doi: 10.2174/0929867043456151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsou CL. Adv. Enzymol. 1988;61:381–436. doi: 10.1002/9780470123072.ch7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.