Abstract

The active form of vitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3) has potent immunomodulatory properties that have promoted its potential use in the prevention and treatment of infectious disease and autoimmune conditions. A variety of immune cells, including macrophages, dendritic cells and activated T cells express the intracellular vitamin D receptor (VDR) and are responsive to 1,25(OH)2D3. Despite this, how 1,25(OH)2D3 regulates adaptive immunity remains unclear, and may involve both direct and indirect effects on the proliferation and function of T cells. To further clarify this issue we have assessed the effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on human CD4+ CD25− T cells. We observed that stimulation of CD4+ CD25− T cells in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IFN- γ, IL-17 and IL-21 but did not substantially affect T cell division. In contrast to its inhibitory effects on inflammatory cytokines, 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulated expression of high levels of CTLA-4 as well as FoxP3, the latter requiring the presence of IL-2. T cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 could suppress proliferation of normally responsive T cells indicating that they possessed characteristics of adaptive Tregs. Our results suggest that 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2 have direct synergistic effects on activated T cells, acting as potent anti-inflammatory agents and physiologic inducers of adaptive Tregs.

Keywords: Human, T cells, Cell differentiation, Tolerance

Introduction

In response to stimulation CD4+ T cells can adopt a variety of different phenotypes which are geared towards specific immune functions. It is well established that Th1 cytokines such as interferon gamma (IFN-γ) provide help for macrophages and cellular immune responses whilst Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4, help B cell class switching and antibody production(1). The involvement of these T cell subsets in autoimmunity and allergy highlights the importance of correct and controlled T cell differentiation in immune function. Recently, additional CD4+ T cell lineages including IL-17 secreting T cells (Th17), regulatory T cells (Treg) and T-follicular helper cells (TFH) have been identified, which arise in response to T cell activation under appropriate conditions(2, 3). Like Th1 and Th2 responses, Th17 cells carry out specific immune functions and are thought to be important in the response to extracellular bacteria such as Klebsiella(4). However, IL-17 is also widely implicated in the development of autoimmune diseases(5), including inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis and EAE (6)making understanding of its regulation important. IL-21, is a new member of the IL-2 family and plays a crucial role in the development of TFH cells which provide help for B cells in germinal centres(3) as well as providing an alternative pathway for Th-17 differentiation. Indeed, overproduction of cells with a TFH phenotype also leads to autoimmunity(7).

Given the importance of T cell differentiation to both immunity and autoimmunity, there is much interest in understanding the factors which influence T cell differentiation. For Treg and Th17 differentiation these factors are now emerging and studies indicate that TGFβ is central to both Treg and Th17 lineages(8). In the presence of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-6, TGFβ appears to promote IL-17 development(6, 9), whereas TGFβ alone stimulates the generation of adaptive Treg, or at least the induction of FoxP3(10-13). Thus inflammatory cytokines are important switch factors in deciding whether inducible Treg or Th17 are produced. In addition it is now clear that IL-2 plays a critical role in the induction and maintenance of Treg being important for TGFβ effects and in the maintenance of FoxP3 expression (13-15).

In addition to cytokines produced by the immune system, environmental or dietary factors can also influence T cell differentiation. Strikingly, retinoic acid (vitamin A) and its derivatives produced by mucosal DC have recently been shown to profoundly affect T cell differentiation(16) (17, 18), resulting in a bias towards Treg and the inhibition of Th-17 cells. In contrast, other compounds such as environmental dioxins can promote Th17 differentiation and suppress Treg development via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (19, 20). Another dietary/environmental factor that may play a significant role in immune regulation is the active form of vitamin D (1,25(OH)2D3) (21) (22). Recent studies have suggested that APCs which express the nuclear vitamin D receptor (VDR) are the major target for the immune suppressive actions of 1,25(OH)2D3 (23, 24) (25), although it is known that activated T cells also express the VDR (26). DCs treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 remain in an immature state with reduced expression of costimulatory molecules and IL-12(23, 25, 27, 28). Whilst these observations have underlined a potential role for 1,25(OH)2D3 in the control of autoimmunity (21) its effect on newly described T cell subsets remains unclear.

Previous studies have demonstrated effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on CD4 T cells, including including the transcriptional regulation of cytokines such as IL-2(29),IFN-γ (30) (31) and IL-4(32), suggesting that it may suppress Th1 and promote Th2 differentiation. However in some cases these early sudies did not adequately dissect between effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on antigen presenting cells or direct effects on T cells. The aim of the current study was to investigate the potential effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on expression of inflammatory cytokines and regulatory markers in T cells. We observed that 1,25(OH)2D3 can act directly on CD4+ T cells to influence their phenotype, downregulating production of the effector cytokines IFN-γ, IL-17 and IL-21. Strikingly, we also observed that following 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment, T cells adopted the phenotypic and functional properties of adaptive Tregs, expressing high levels of CTLA-4 and FoxP3. T cells cultured in the presence of both 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2 expressed the highest levels of CTLA-4 and FoxP3 and possessed the ability to suppress proliferation of resting CD4+ T cells. These data suggest that 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2 can directly suppress the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and may therefore be important factors which influence susceptibility to autoimmune diseases.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

1,25(OH)2D3 was obtained as a gift from Dr Lise Binderup (Leo Pharma, Denmark). In each experiment 1,25(OH)2D3 was used at a concentration of 100nM or at the concentrations stated. Dilutions to 100μM were made in ethanol from a 4mM stock in isopropanol and then to the concentration desired in medium. Ethanol (Control) was used as a vehicle control in all cases. Cells were cultured in complete RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin and streptomycin (50U/ml), 200μM glutamine (Gibco, Invitrogen, UK).

Antibodies

The following monoclonal antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences Europe: anti-human CD4 conjugated to FITC (RPA-T4), anti-human CTLA-4, CD152 (BN13) conjugated to PE, anti-IFN-γ (B27) conjugated to APC and anti-IL-2(MQ1-17H12) conjugated to PE, anti-human IL-10 (JES3-9D7) conjugated to PE. The following monoclonal antibodies were purchased from eBioscience: Anti-human IL-17 (ebio64CAP17) conjugated to PE, anti-human IL-21 (ebio3A3-N2) conjugated to PE and anti-human FoxP3 (PCH101) conjugated to APC, which was purchased as part of a FoxP3 staining kit. Isotype matched controls conjugated to the appropriate fluorochrome were purchased from BD Bioscience and eBioscience and used to control for non-specific binding.

Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC)

PBMC were isolated from fresh buffy coats (provided by the National blood Service, Birmingham, UK), using Ficoll-Paque density gradient centrifugation. Cells were washed by centrifugation twice in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) then resuspended at 1 × 108/ml in MACS buffer (0.5% bovine serum albumin and 2mM EDTA in phosphate buffered saline) for magnetic cell separation (see below). Blood was obtained from anonymised donors following informed consent and in line with institutional and ethical committee approval.

Purification of CD4+ CD25− T cells

CD4+ T cells were separated by negative selection using human CD4 enrichment antibody cocktail and magnetic colloid (StemSep™) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (StemCell Technologies, UK). To separate CD4+ CD25+ T cells from CD4+ CD25− T cells the CD4+ T cells were incubated with anti-CD25 conjugated microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, UK) for 30 minutes at 4°C and then passed over a column. The negative fraction was collected from the column and used as described.

CD4+ CD25− T cell stimulation

1 × 105 anti-CD3, anti-CD28 antibody coated beads (Dynal, Invitrogen)-hereafter referred to as “beads” were used to activate CD4+ T cells at a ratio of 1: 1 in the presence or absence of 1,25(OH)2D3 at a concentration of 100nM unless otherwise indicated. Cells were cultured in RPMI plus 10%FBS at 37°C. For experiments using monocytes, monocytes were separated from PBMC by negative selection using human monocyte enrichment antibody cocktail and magnetic colloid (StemSep™) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (StemCell Technologies, UK) and used to stimulate T cells at a ratio of 1:4 in the presence of 0.1μg/ml of anti-CD3 (clone OKT3)

Flow cytometry

For analysis of surface proteins, CD4+ T cells were washed by centrifugation in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and labelled with the indicated monoclonal antibody for 30 minutes on ice. For intracellular staining, cells were washed by centrifugation in PBS and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 minutes prior to permeabilisation in buffer containing 0.1% saponin. Non specific antibody binding to Fc receptors was blocked by incubation in 0.1% saponin containing 2% goat serum for 30 minutes at room temperature. Labelled monoclonal antibodies were then added and cells incubated a further 30 minutes at room temperature. Finally, cells were washed by centrifugation once in permeabilisation buffer and twice in PBS prior to acquisition on the flow cytometer. For intracellular cytokine staining, prior to labelling as described above, CD4+ T cells were stimulated with 10ng/ml PMA and 1μM Ionomycin for 7 hours in the presence of 10μg/ml Brefeldin A for the last 5 hours (all purchased from Sigma, UK). FoxP3 staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using a FoxP3 staining kit purchased from eBioscience, San Diego. For staining of re-cycling CTLA-4, T cells were incubated with anti-CTLA-4-PE at 37°C as previously described(33). For cytokine staining quadrants were set according to the position of the density of the non-staining cells and for CTLA-4 and FoxP3 set according to unstimulated cells. Cells were acquired on the FACSCalibur Flow Cytometer, BD and analysed using FlowJo software.

CD4+ T cell Proliferation Assays

Proliferation of activated CD4+ T cells was measured by dilution of CFSE. For these experiments, T cells were washed two times in PBS and then incubated with 2.5μM CFSE for 10 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation. The reaction was quenched by addition of medium and the cells washed two times by centrifugation in medium. Cells were then resuspended at 2 × 106/ml in medium and plated at a concentration of 105 cells per well in 96 well plates and activated as described above. At day 5 CFSE dilution was measured by flow cytometry.

Re-stimulation and Suppression Assays

For re-stimulation assays, CD4+ T cells were primed with monocytes plus anti-CD3 (0.1μg/ml) in the presence or absence of 1,25(OH)2D3 (100nM) and IL-2 (200IU/ml) for 7 days. T cells were re-stimulated as shown for a further 4 days and stained by flow cytometry. For suppression assays, CD4+CD25− T cells were primed with monocytes and anti-CD3 in the presence or absence of 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2 for 8 days. Cells were then added at the ratio of 1:10 with fresh CFSE labelled responder CD4+CD25− T cells in a proliferation assay stimulated by autologus monocyte-derived dendritic cells grown as previously described (40) plus anti-CD3(0.5μg/ml). Proliferation was measured by CFSE dilution analysis.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol method (Invitrogen). 1μg per reaction was reverse transcribed with random hexamers (Fermentas Life Sciences). Quantitative real-time PCR was then performed on an ABI 7500 using assay on demand from Applied Biosystems for IL-17A (Hs99999082), IFNγ (Hs00174143), CTLA4 (Hs00175480) and FoxP3 (Hs00203958). The reactions were multiplexed with VIC labelled 18S (Applied Biosystems) as an endogenous control and analysed by the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Statistical analysis

P values were calculated by a two-tailed Wilcoxon matched pairs test or two tailed Mann-Whitney test, as indicated in figure legends, using GraphPad Prism3 Software.

Results

1,25(OH)2D3 treatment inhibits T cell inflammatory cytokine production, but not proliferation

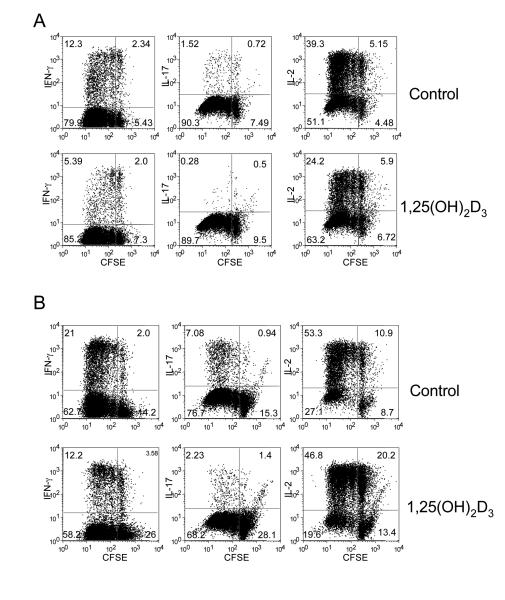

To assess the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on CD4+ CD25− T cell responses, we CFSE labelled and activated cells with anti-CD3, anti-CD28 coated beads (beads) in the presence or absence of 100nM of 1,25(OH)2D3. This dose was found to be optimal, although similar effects were readily observed at doses of between 10-100nM (data not shown). The effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the production of IL-2, IFN-γ and IL-17 was then determined in the context of T cell division. As shown in Figure 1A, 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment caused a marked decrease in the total number of cells producing IFN-γ. Interestingly, whilst the number of IL-17-producing cells was small, we observed a decrease in response to 1,25(OH)2D3. IL–2 production was also reduced in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3. Thus 1,25(OH)2D3 appeared to have a general inhibitory effect on effector cytokine production. Despite these decreases in cytokine production, 1,25(OH)2D3 had no obvious effect on CD4+ T cell proliferation with approximately 90% of cells entering cell division.

Figure 1. 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibits T cell cytokine production without affecting cell division.

(A) Purified CD4+CD25− T cells were CFSE-labelled and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 coated beads in the presence or absence of 100nM 1,25(OH)2D3 for 5 days. Following stimulation cells were stained for IL-2, IFN-γ and IL-17 production and analysed for cell division by FACS. (B) Purified CD4+CD25− were treated as in A except that cells were stimulated with autologous monocytes plus anti-CD3. Data is from a single experiment representative of 3 performed.

Whilst these experiments established that 1,25(OH)2D3 could exert direct effects on T cells, in the absence of APCs, we also determined whether the inhibition of inflammatory cytokines, in particular IL-17, could be modulated by 1,25(OH)2D3 in the presence of a more potent IL-17 stimulus. The above experiment was therefore repeated with CD4+CD25− T cells in the presence of autologous monocytes plus anti-CD3 to promote the Th17 population as previously described(34). Consistent with our observations using beads, we observed that 1,25(OH)2D3 potently inhibited IFN-γ and IL-17 production (Figure 1B). There was also a slight reduction in the number of cells entering division suggesting that there may be an effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the ability of monocytes to stimulate in these cultures.

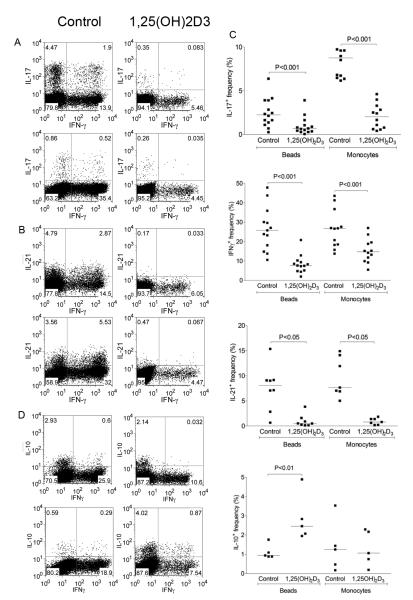

Additional experiments were then performed to look in more detail at the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the ability of T cells to co-produce IL-17 plus IFN-γ as these populations are increased during autoimmune disease in vivo (35, 36). This revealed that 1,25(OH)2D3 potently inhibited the appearance of cells producing IL-17 or IFN-γ alone, as well as cells that produced both cytokines (Figure 2A). Likewise the production of IL-21 by T cells in both IFN-γ positive and negative subsets was inhibited (Figure 2B). Again the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on co-production of cytokines was observed using either bead or monocyte stimulations, indicating that 1,25(OH)2D3 was capable of inhibiting production of IL-17, IL-21 and IFN-γ through a direct effect on T cells. Collectively these data showed that irrespective of whether the T cells were stimulated in the presence or absence of APC, addition of 1,25(OH)2D3 resulted in a robust and highly significant inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which was reproducibly observed across multiple donors examined (Figure 2C). To determine whether 1,25(OH)2D3 resulted in inhibition of all cytokines, we also examined its effect on IL-10, since 1,25(OH)2D3 has previously been reported to enhance IL-10 production(37). Consistent with previous findings, we observed that 1,25(OH)2D3 increased IL-10 (Figure 2D) and was therefore clearly selective in its inhibitory action.

Figure 2. 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibits IL-17, IFN-γ and IL-21 but promotes IL-10.

Purified CD4+CD25− T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 coated beads or autologous monocytes plus anti-CD3 (0.1μg/ml) in the presence of 100nM 1,25(OH)2D3 or vehicle control for 5 days. Following stimulation cells were stained for IFN-γ and co stained for IL-17 (A) IL-21 (B) and IL-10 (D). Upper panels were stimulated with autologous monocytes plus anti-CD3 and lower panels with beads. Data from multiple experiments are represented in panel C. Horizontal bars indicate the median frequency. Significance was tested by a two-tailed Wilcoxon matched pairs test.

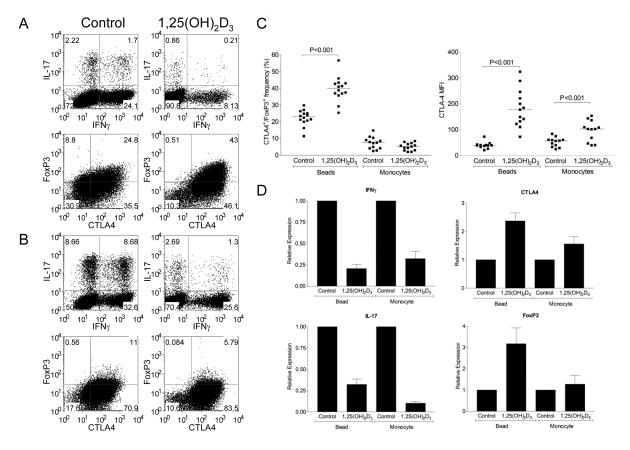

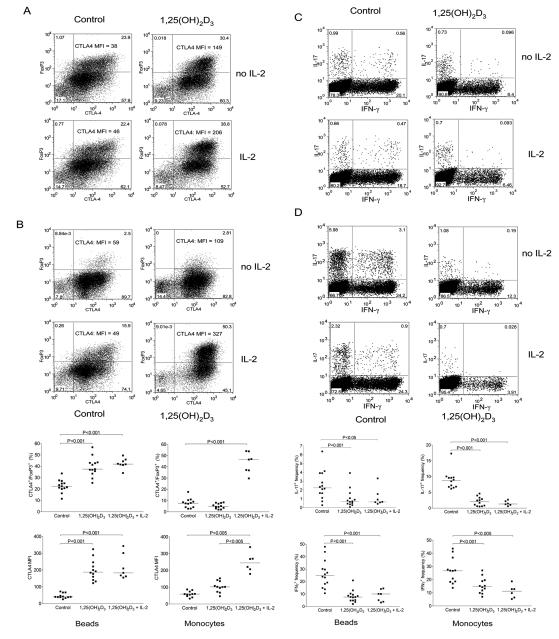

1,25(OH)2D3 upregulates CTLA-4 and FoxP3

We next wished to establish whether treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 could promote alternative T cell lineages since Th17 and Treg cells appear to be related fates in T cell differentiation(6, 8, 9). We therefore examined FoxP3 and CTLA-4 expression during CD4+ T cell activation along with IL-17 and IFN-γ production (Figure 3). Stimulation with beads generated a population of cells expressing both CTLA-4 and FoxP3 and the addition of 1,25(OH)2D3 significantly increased this population (Figure 3A and 3C). Furthermore, in addition to the increase in the number of cells expressing FoxP3 and CTLA4, the level of CTLA-4 expression also increased. These changes were accompanied by the characteristic inhibition of IFN-γ and IL-17 expression upon 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment, indicating that whilst 1,25(OH)2D3 suppressed inflammatory outcomes it also promoted regulatory ones.

Figure 3. 1,25(OH)2D3 promotes expression of CTLA-4 and FoxP3.

Purified CD4+CD25− T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 coated beads (A) or autologous monocytes plus anti-CD3 (0.1μg/ml) (B) in the presence of 100nM 1,25(OH)2D3 or vehicle control for 5 days. Following stimulation cells were stained for total expression of CTLA-4 and FoxP3 or IFN-γ and IL-17. Numbers in quadrants refer to percentage of cells. Data from multiple experiments for CTLA-4 and FoxP3 expression are represented in panel C. Horizontal bars indicate the median value and significance was tested by a two-tailed Wilcoxon matched pairs test. Quantitative PCR analysis of mRNA expression for CTLA-4, FoxP3, IL-17 and IFNγ is shown in D. Bars indicate the mean relative expression with respect to the control for n=3 donors. Error bars show the standard error.

Surprisingly, when T cells were stimulated with monocytes plus anti-CD3, we did not observe a significant population of cells expressing FoxP3 either in the presence or absence of 1,25(OH)2D3 (Figure 3B). These above effects were observed in multiple experiments (Figure 3C) using different donors. Interestingly, we did observe increased CTLA-4 expression in the absence of any changes in FoxP3 using monocyte stimulations, suggesting that the effect on CTLA-4 expression was independent of its induction of FoxP3. Finally we also examined whether these changes in expression pattern were reflected at the transcriptional level, using quantitative PCR (Figure 3D). This revealed that for CTLA-4, FoxP3, IL-17 and IFNγ, changes in mRNA paralleled those of the protein, suggesting that 1,25(OH)2D3 acts to affect transcription of these genes.

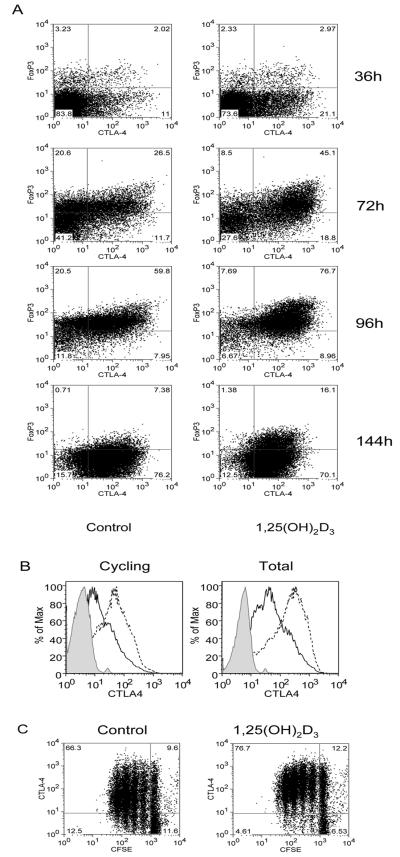

Since the expression of FoxP3 in induced Treg is thought to be transient(38, 39), we analysed the kinetics of the response to determine if 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment was able to sustain the expression of CTLA-4 and FoxP3. As shown in Figure 4, treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 resulted in cells that expressed higher levels of CTLA-4 at all time points as well as an increased population of cells expressing FoxP3. However, by the end of the stimulation period, the expression of CTLA-4 and FoxP3 had reduced considerably both in the presence and absence of 1,25(OH)2D3. Thus whilst 1,25(OH)2D3 promoted expression of characteristic Treg markers, it did not result in stable expression of these markers after a single round of stimulation. Furthermore re-addition of 1,25(OH)2D3 at day 4 did not prevent this downregulation (data not shown). We also investigated whether the increase in total CTLA-4 staining reflected the amount of CTLA-4 that was actually turned over at the plasma membrane and therefore functionally relevant. As shown in Figure 4B, treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 increased both the total and re-cycling pools of CTLA-4 in a similar manner. We also determined whether cells with increased CTLA-4 expression were the result of outgrowth of a selected CTLA-4-high population (Figure 4C). By staining for CTLA-4 expression in CFSE labelled cells we observed that 1,25(OH)2D3 increased CTLA-4 expression even in undivided cells (control MFI = 95 vs treated MFI = 174). Since we did not observe increased cell death in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3, this supported the possibility that 1,25(OH)2D3 could be influencing the differentiation T cells expressing high levels of CTLA-4.

Figure 4. Expression of FoxP3 is not stably maintained by 1,25(OH)2D3.

(A) Purified CD4+CD25− T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 coated beads in the presence of 100nM 1,25(OH)2D3 or vehicle control for the times shown. Cells were analysed for expression of CTLA-4 and FoxP3. (B) Expression was determined for both the total and re-cycling pool of CTLA-4. Dotted lines indicate expression in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 whereas black lines indicate vehicle control. The shaded histogram represents isotype control staining. (C) CFSE labelled CD4+ CD25− T cells were stimulated as above and analysed for CTLA-4 expression in combination with cell division. Numbers in quadrants refer to percentage of cells. Data shown is from a single experiment representative of 3 carried out.

Induction of FoxP3 and CTLA-4 involves synergy between 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2

A feature of T cell stimulation by anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies is the production of large amounts of IL-2. Since IL-2 is known to play a key role in regulating FoxP3 expression we reasoned that the lack of FoxP3 expression in monocyte stimulated cultures could be due to a relative lack of this cytokine. We therefore examined the effect of IL-2 supplementation to both bead and monocyte stimulated cultures to determine whether or not this affected responses to 1,25(OH)2D3. As shown in Figure 5, the addition of IL-2 alone to bead stimulations had no obvious effect on FoxP3 and CTLA-4 expression (Figure 5A) or the cytokine profile (Figure 5C). However, IL-2 together with 1,25(OH)2D3 resulted in a robust population of CTLA4 and FoxP3 double positive cells and was associated with a concommitant decrease in IL-17 or IFN-γ expressing cells (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2 synergise to promote regulatory T cell development and inhibit inflammatory cytokine production.

(A + C) CD4+CD25− T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 coated beads in the presence of 100nM 1,25(OH)2D3 or vehicle control with or without the addition of IL-2 (200IU/ml). (B + D) Purified CD4+CD25− were stimulated with autologous monocytes plus anti-CD3 in the presence of 100nM 1,25(OH)2D3 or vehicle control with or without the addition of IL-2 (200IU/ml). Cells were analysed for CTLA-4 and FoxP3 expression panels A and B or for cytokine expression (C and D). Numbers in quadrants refer to percentage of cells. CTLA-4 MFI is also shown. Summary data from multiple independent experiments are show in panel E. Horizontal bars indicate median values. Significance was tested using a two-tailed Wilcoxon matched pairs test.

In contrast, T cells cultured with monocytes and anti-CD3 alone did not generate FoxP3 expressing cells, however, addition of IL-2 clearly allowed the induction of FoxP3 (Figure 5B). Addition of 1,25(OH)2D3 alone increased expression of CTLA-4 but not FoxP3. However, the addition of both IL-2 and 1,25(OH)2D3 resulted in a strong synergistic effect with approximately half of the cells expressing high levels of CTLA-4 and FoxP3, characteristic of Treg cells. Furthermore, the development of CTLA-4+FoxP3+ cells coincided with the strong inhibition of cells expressing IL-17 or IFN-γ (Figure 5 D). These findings were robustly observed in several experiments using different donors (Figure 5E) and overall indicate that IL-2 and 1,25(OH)2D3 have a synergistic anti-inflammatory and pro-regulatory effect on human CD4+ CD25− T cells.

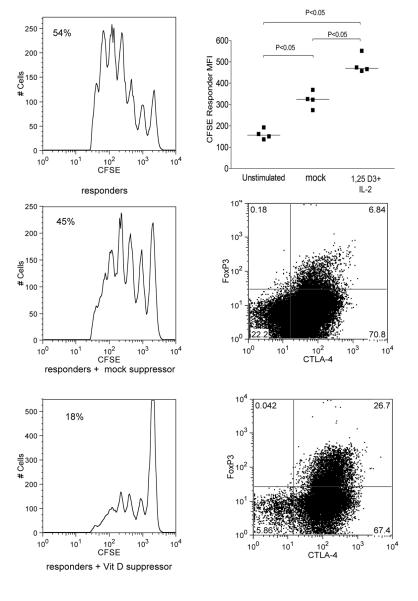

To determine if T cell cultures treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2 exhibited suppressive activity, we carried out suppression assays where CFSE labelled responder T cells were stimulated by dendritic cells plus anti-CD3 in the presence of potential suppressor T cells. Potential suppressors were generated by stimulating T cells with monocytes plus 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2 and compared to T cells stimulated in their absence. The result of this experiment (Figure 6) clearly showed that T cells stimulated with monocytes plus anti-CD3 in the presence of IL-2 and 1,25(OH)2D3 comprised a increased population of cells expressing CTLA-4 and FoxP3. Furthermore, when compared to T cells from untreated cultures, those treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2 demonstrated greater suppression of responder T cell proliferation as measured by CFSE dilution.

Figure 6. T cell culture in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2, results in suppressive function.

Suppressor CD4+ T cells were generated by stimulating purified CD4+CD25− with autologous monocytes plus anti-CD3 in the presence of 100nM 1,25(OH)2D3 and addition of IL-2 (200IU/ml) for 7 days. Cells cultured without 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2 were used as mock-suppressor populations. Suppressor mock-suppressor populations were added at a ratio of 1:10 CFSE labelled responder T cells and stimulated by dendritic cells plus anti-CD3 at a ratio of 1:5 DCs : T cells. Responses were also compared to unstimluated, (resting CD4+ cells) as suppressor controls. Responder CFSE profiles are shown with the % cells entering cell division (left panels) along with the phenotype of suppressor and mock-suppressor cells (right panel).CFSE profiles are from a single experiment of four performed. Data showing individual experiments are summarised as median fluorescence intensity (CFSE responder MFI) in the top right panel. Data were analysed using the Mann-Whitney test. Dot plots show typical expression of CTLA-4 and FoxP3 in cells with and without treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 plus IL-2.

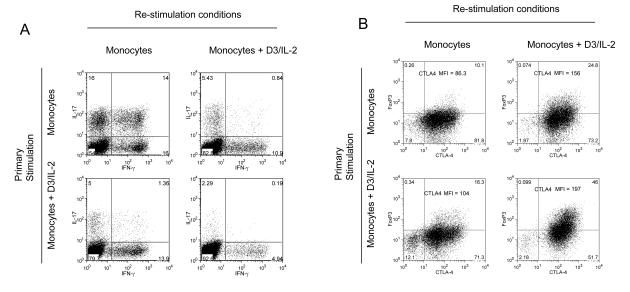

The effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2 on FoxP3 and CTLA-4 expression is sustained on restimulation

Since potential immunotherapies will most likely be directed at conditions where T cell activation and differentiation are already established, we carried out re-stimulation experiments to determine the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2 on previously activated cells. Cultures were initially stimulated with monocytes plus anti-CD3 in the presence or absence of 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2 for 8 days to allow initial responses to develop. The cells were then re-stimulated under a variety of conditions and their expression of cytokines, CTLA-4 and FoxP3 determined. Data in Figure 7 revealed that cells initially stimulated then re-stimulated with monocytes underwent further polarisation towards IL-17 and IFN-γ production, with some 30% of cells expressing IL-17 (Figure 7A). These cells expressed little FoxP3 and low levels of CTLA-4 (Figure 7B). In contrast, cells that were both primed and restimulated in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2 contained less than 3% of cells expressing IL-17 and strongly reduced IFN-γ expression. As expected, these cells expressed high CTLA-4 and FoxP3. Importantly, cells that had been primed in the presence of monocytes to express IL-17 and IFN-γ were still inhibited by the addition of 1,25(OH)2D3 during re-stimulation. Thus, in keeping with our previous observations, cells with the greatest inhibition of cytokine production also demonstrated the greatest increase in CTLA-4 and FoxP3 expression (Figure 7B). Taken together these data indicate that 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2 act to inhibit inflammatory cytokine production and promote a regulatory T cell phenotype, an effect which can be maintained by T cell re-stimulation.

Figure 7. Effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-2 is maintained on activated T cells.

CD4+CD25− T cells were stimulated in primary culture with monocytes and anti-CD3 for 7 days with or without1,25(OH)2D3 plus IL-2 (D3/IL-2) (y axis) and then re-stimulated with monocytes and anti-CD3 for a further 4 days under conditions shown (x-axis). The phenotype of the re-stimulated cells was then assessed for cytokine production (panel A) or FoxP3 and CTLA-4 expression (Panel B). Numbers in quadrants refer to percentage of cells and CTLA-4 MFI intensity is also shown. Data are from a single experiment representative of 3 performed.

Discussion

Vitamin D status is emerging as a global health issue with an increasing number of human diseases being linked to vitamin D deficiency(40). These observations have been supported by recent studies highlighting a diverse array of non-classical responses to vitamin D. Prominent amongst these are studies demonstrating potent effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on immune cells (22), in particular cells of the innate immune system(41, 42). Indeed, the effects of active 1,25(OH)2D3 have focused primarily on effects on DCs (23, 43-46). Consequently, effects on CD4+ T cells have been seen as indirect, via DC modulation. Immature DCs express VDR and respond directly to 1,25(OH)2D3 which inhibits their differentiation, maturation and activation(25). This results in decreased expression of co-stimulatory molecules, inhibition of IL-12 production (25), (23, 45) and impaired T cell responses. Interestingly, we did not observe any effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the number of T cell divisions when stimulated in the absence of APC. Therefore, it seems likely that the decreased proliferation of T cells ascribed to 1,25(OH)2D3 results from impaired APC function.

Importantly, DCs and macrophages may be an important immune source of active 1,25(OH)2D3 for direct effects on T cells since it is known that they are able to generate 1,25(OH)2D3 due to their expression of the enzyme 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1α-hydroxylase(25). This complicates the issues of physiologically relevant doses of 1,25(OH)2D3 which may be present at higher concentrations locally within immune tissue than measured systemically. Whilst we have utilised a relatively high dose of 1,25(OH)2D3 in the present studies, we are able to observe responses at lower concentrations (1-10 nM) which are comparable with levels generated by DCs in vitro (47) and with therapeutically achievable doses in clinical studies.

In addition to the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on T cell proliferation, we have examined its role in CD4+ CD25− T cell differentiation. Recent observations have underlined the increasing plasticity found within the T cell lineage. This has established that resting CD4+ CD25− T cells can be differentiated towards a FoxP3+ regulatory lineage under the influence of cytokines such as TGFβ (38, 48). Interestingly, this effect is further enhanced by vitamin A derivatives(16). However, inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and IL-6 have the ability to re-direct this differentiation towards the IL-17 lineage(8). In the present experiments we observed unequivocally that purified human T cells activated in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 expressed markedly reduced levels of IL-17, IFN-γ and IL-21, hallmark cytokines of Th-17, Th-1 and T-FH effector responses respectively. Thus 1,25(OH)2D3 is able to inhibit T cell differentiation towards effector functions independently of effects on APC. However, rather than simply inhibiting effector cytokine production, our data show that 1,25(OH)2D3 promotes a regulatory outcome as evidenced by high levels of CTLA-4 expression and FoxP3 and the induction of IL-10. Taken together with the fact that we see no preferential expansion of T cells or increased death in our cultures, these observations are consistent with an effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on T cell differentiation possibly similar to the of vitamin A(16, 18). The effect on FoxP3 and CTLA-4 was initially more noticeable using T cells stimulated by antibody coated beads. However, the lack of FoxP3 in monocyte stimulated cultures appears to be due to the relative lack of IL-2 since addition of IL-2 resulted in strong upregulation of FoxP3. These data are therefore in line with several reports indicating that IL-2 is a key regulatory cytokine controlling FoxP3 expression(13, 15), further emphasising the regulatory role of IL-2.

Whilst the study of in vitro effects on T cell responses has limitations, the induction of regulatory responses by 1,25(OH)2D3 has also been studied in vivo using mouse models. In particular, administration of 1,25(OH)2D3 to non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice results in decreased Th1 cell infiltration in the pancreas, prevention of insulitis and the onset of diabetes(49). Adorini et al. also showed that these effects were paralleled by an increase in the frequency of regulatory–type cells in draining pancreatic lymph nodes although the FoxP3 status of these cells was not ascertained(44). 1,25(OH)2D3 has also been shown to have effects on regulatory outcomes involving IL-10 in EAE models(50) and in an induced colitis mouse model 1,25(OH)2D3 demonstrated a change towards a Treg phenotype (51). Furthermore the in vivo observation that 1,25(OH)2D3 can inhibit IL-17 responses, provides considerable support for our in vitro observations using human T cells(52). The concept that vitamin D may enhance CTLA-4 expression and therefore Treg function is also consistent with a recent study where the application of topical vitamin D resulted in enhanced Treg activity(53). More intriguingly, in human sarcoidosis where there is dramatically increased production of 1,25(OH)2D3, an unusually high number of Treg with high expression of CTLA-4 is observed(54, 55). This observation is entirely in keeping with the results presented here and supports the contention that 1,25(OH)2D3 can significantly affect Treg differentiation in vivo. Whilst it is not clear from in vivo studies whether the induction of Tregs by 1,25(OH)2D3 is due to indirect actions via DCs or whether this occurs as a result of generation of de novo adaptive Tregs, data presented here would argue that such an effect could result from the direct induction of CTLA-4 and FoxP3 during differentiation of T cells in response to 1,25(OH)2D3.

The generation of de novo FoxP3 expressing T cells is now an accepted facet of Treg biology. A number of reports have now convincingly demonstrated the differentiation of adaptive FoxP3+ Tregs from FoxP3− CD4 T cells. The conditions for such conversion vary widely and include activation in the presence of immunomodulatory agents, such as TGFβ (12) (56), the use of low doses of peptides(57 )and simple adoptive transfer of T cells(58). In humans, the requirements for FoxP3 upregulation appear less stringent with studies showing that essentially normal activation is sufficient to induce a cohort of cells that express FoxP3 (59) although it seems likely TGFβ is present in serum. Whilst it is recognised that TGFβ can be a significant factor involved in Treg differentiation, the effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 seem distinct from this pathway. Since our cultures were carried out in serum containing medium, the effects we observed are in addition to the endogenous TGFβ present. Furthermore, we have not observed upregulation of CTLA-4 or supression of cytokines by adding TGFβ to our cultures in contrast to 1,25(OH)2D3. Whilst we do not rule out an interaction between the 1,25(OH)2D3 and TGFβ pathways, the effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 appear to be distinct and in addition to those of TGFβ.

The importance of CTLA-4 expression in Treg function is now beginning to clearly emerge. Several reports have indicated that CTLA-4 can play an important role in the suppressive activity of Treg (60-62). Recently we have observed that CTLA-4-deficient Treg have compromised function in a model of diabetes(63) and conditional deletion of CTLA-4 in Treg cells has been shown to cause fatal autoimmunity(64). We have also shown that expression of CTLA-4 confers regulatory activity to resting human T cells, whereas FoxP3 does not (65). Thus, expression of CTLA-4 appears to represent an important effector mechanism for Treg suppression. It is therefore most significant that stimulation of T cells in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 results in the strong upregulation of CTLA-4 and associated suppressive function.

It is now established that FoxP3+ regulatory T cells are critical to the prevention of catastrophic autoimmunity. The maintenance of a significant population of such cells is therefore required for lifelong health. Our data show that 1,25(OH)2D3 has a significant and direct effect on the generation of FoxP3+ CTLA-4+ Treg which are capable of potent immune suppression. Coupled with increasing data linking autoimmune disease with low vitamin D status and polymorphisms in the gene for VDR(66), (40, 67), our data offer potential insight into the importance of vitamin D in the prevention and/or treatment of autoimmune disease.

Acknowledgments

Louisa Jeffery is supported by The Arthritis Research Campaign. Fiona Burke and Manuela Mura were supported by BBSRC grant (BBS/B/01014). Omar Qureshi is supported by the BBSRC, Lucy Walker is an MRC Senior Research Fellow. MH is supported by NIH grant R01 2154380.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Journal of Immunology (The JI). The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. (AAI), publisher of The JI, holds the copyright to this manuscript. This manuscript has not yet been copyedited or subjected to editorial proofreading by The JI; hence it may differ from the final version published in The JI (online and in print). AAI (The JI) is not liable for errors or omissions in this author-produced version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by the United States National Institutes of Health or any other third party. The final, citable version of record can be found at www.jimmunol.org.”

References

- 1.O’Garra A, Murphy K. Role of cytokines in determining T-lymphocyte function. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6:458–466. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. T(H)-17 cells in the circle of immunity and autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:345–350. doi: 10.1038/ni0407-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogelzang A, McGuire HM, Yu D, Sprent J, Mackay CR, King C. A fundamental role for interleukin-21 in the generation of T follicular helper cells. Immunity. 2008;29:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Happel KI, Dubin PJ, Zheng M, Ghilardi N, Lockhart C, Quinton LJ, Odden AR, Shellito JE, Bagby GJ, Nelson S, Kolls JK. Divergent roles of IL-23 and IL-12 in host defense against Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Exp Med. 2005;202:761–769. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, Mattson J, Basham B, Sedgwick JD, McClanahan T, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:233–240. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu D, Tan AH, Hu X, Athanasopoulos V, Simpson N, Silva DG, Hutloff A, Giles KM, Leedman PJ, Lam KP, Goodnow CC, Vinuesa CG. Roquin represses autoimmunity by limiting inducible T-cell co-stimulator messenger RNA. Nature. 2007;450:299–303. doi: 10.1038/nature06253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manel N, Unutmaz D, Littman DR. The differentiation of human T(H)-17 cells requires transforming growth factor-beta and induction of the nuclear receptor RORgammat. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:641–649. doi: 10.1038/ni.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marie JC, Letterio JJ, Gavin M, Rudensky AY. TGF-beta1 maintains suppressor function and Foxp3 expression in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1061–1067. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fantini MC, Becker C, Monteleone G, Pallone F, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Cutting edge: TGF-beta induces a regulatory phenotype in CD4+CD25− T cells through Foxp3 induction and down-regulation of Smad7. J Immunol. 2004;172:5149–5153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wan YY, Flavell RA. Identifying Foxp3-expressing suppressor T cells with a bicistronic reporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5126–5131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501701102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidson TS, DiPaolo RJ, Andersson J, Shevach EM. Cutting Edge: IL-2 is essential for TGF-beta-mediated induction of Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:4022–4026. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng SG, Wang J, Wang P, Gray JD, Horwitz DA. IL-2 is essential for TGF-beta to convert naive CD4+CD25− cells to CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells and for expansion of these cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:2018–2027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Setoguchi R, Hori S, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi S. Homeostatic maintenance of natural Foxp3(+) CD25(+) CD4(+) regulatory T cells by interleukin (IL)-2 and induction of autoimmune disease by IL-2 neutralization. J Exp Med. 2005;201:723–735. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mucida D, Park Y, Kim G, Turovskaya O, Scott I, Kronenberg M, Cheroutre H. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science. 2007;317:256–260. doi: 10.1126/science.1145697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y, Powrie F. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denning TL, Wang YC, Patel SR, Williams IR, Pulendran B. Lamina propria macrophages and dendritic cells differentially induce regulatory and interleukin 17-producing T cell responses. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1086–1094. doi: 10.1038/ni1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veldhoen M, Hirota K, Westendorf AM, Buer J, Dumoutier L, Renauld JC, Stockinger B. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature. 2008;453:106–109. doi: 10.1038/nature06881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quintana FJ, Basso AS, Iglesias AH, Korn T, Farez MF, Bettelli E, Caccamo M, Oukka M, Weiner HL. Control of T(reg) and T(H)17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature. 2008;453:65–71. doi: 10.1038/nature06880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adorini L, Penna G. Control of autoimmune diseases by the vitamin D endocrine system. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:404–412. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams JS, Hewison M. Unexpected actions of vitamin D: new perspectives on the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008;4:80–90. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penna G, Amuchastegui S, Giarratana N, Daniel KC, Vulcano M, Sozzani S, Adorini L. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d3 selectively modulates tolerogenic properties in myeloid but not plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J.Immunol. 2007;178:145–153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffin MD, Xing N, Kumar R. Vitamin D and its analogs as regulators of immune activation and antigen presentation. Annu Rev Nutr. 2003;23:117–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.23.011702.073114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hewison M, Freeman L, Hughes SV, Evans KN, Bland R, Eliopoulos AG, Kilby MD, Moss PA, Chakraverty R. Differential regulation of vitamin D receptor and its ligand in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:5382–5390. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhalla AK, Amento EP, Clemens TL, Holick MF, Krane SM. Specific high-affinity receptors for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: presence in monocytes and induction in T lymphocytes following activation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57:1308–1310. doi: 10.1210/jcem-57-6-1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffin MD, Lutz W, Phan VA, Bachman LA, McKean DJ, Kumar R. Dendritic cell modulation by 1alpha,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 and its analogs: a vitamin D receptor-dependent pathway that promotes a persistent state of immaturity in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6800–6805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121172198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adorini L, Giarratana N, Penna G. Pharmacological induction of tolerogenic dendritic cells and regulatory T cells. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alroy I, Towers TL, Freedman LP. Transcriptional repression of the interleukin-2 gene by vitamin D3: direct inhibition of NFATp/AP-1 complex formation by a nuclear hormone receptor. Mol.Cell Biol. 1995;15:5789–5799. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rigby WF, Denome S, Fanger MW. Regulation of lymphokine production and human T lymphocyte activation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Specific inhibition at the level of messenger RNA. J.Clin.Invest. 1987;79:1659–1664. doi: 10.1172/JCI113004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller K, Bendtzen K. Inhibition of human T lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Differential effects on CD45RA+ and CD45R0+ cells. Autoimmunity. 1992;14:37–43. doi: 10.3109/08916939309077355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boonstra A, Barrat FJ, Crain C, Heath VL, Savelkoul HF, O’Garra A. 1alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin d3 has a direct effect on naive CD4(+) T cells to enhance the development of Th2 cells. J.Immunol. 2001;167:4974–4980. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mead KI, Zheng Y, Manzotti CN, Perry LC, Liu MK, Burke F, Powner DJ, Wakelam MJ, Sansom DM. Exocytosis of CTLA-4 Is Dependent on Phospholipase D and ADP Ribosylation Factor-1 and Stimulated during Activation of Regulatory T Cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:4803–4811. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans HG, Suddason T, Jackson I, Taams LS, Lord GM. Optimal induction of T helper 17 cells in humans requires T cell receptor ligation in the context of Toll-like receptor-activated monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17034–17039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708426104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGeachy MJ, Bak-Jensen KS, Chen Y, Tato CM, Blumenschein W, McClanahan T, Cua DJ. TGF-beta and IL-6 drive the production of IL-17 and IL-10 by T cells and restrain T(H)-17 cell-mediated pathology. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/ni1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korn T, Bettelli E, Gao W, Awasthi A, Jager A, Strom TB, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-21 initiates an alternative pathway to induce proinflammatory T(H)17 cells. Nature. 2007;448:484–487. doi: 10.1038/nature05970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barrat FJ, Cua DJ, Boonstra A, Richards DF, Crain C, Savelkoul HF, de Waal-Malefyt R, Coffman RL, Hawrylowicz CM, O’Garra A. In vitro generation of interleukin 10-producing regulatory CD4(+) T cells is induced by immunosuppressive drugs and inhibited by T helper type 1 (Th1)- and Th2-inducing cytokines. J Exp Med. 2002;195:603–616. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tran DQ, Ramsey H, Shevach EM. Induction of FOXP3 expression in naive human CD4+FOXP3− T cells by T cell receptor stimulation is TGF{beta}-dependent but does not confer a regulatory phenotype. Blood. 2007;110:2983–2990. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-094656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allan SE, Crome SQ, Crellin NK, Passerini L, Steiner TS, Bacchetta R, Roncarolo MG, Levings MK. Activation-induced FOXP3 in human T effector cells does not suppress proliferation or cytokine production. Int Immunol. 2007;19:345–354. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hewison M. Vitamin D and innate immunity. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;9:485–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.White JH. Vitamin d signaling, infectious diseases, and regulation of innate immunity. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3837–3843. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00353-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Penna G, Giarratana N, Amuchastegui S, Mariani R, Daniel KC, Adorini L. Manipulating dendritic cells to induce regulatory T cells. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:1033–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adorini L. Tolerogenic dendritic cells induced by vitamin D receptor ligands enhance regulatory T cells inhibiting autoimmune diabetes. Ann.N.Y.Acad.Sci. 2003;987:258–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb06057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Penna G, Adorini L. 1 Alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits differentiation, maturation, activation, and survival of dendritic cells leading to impaired alloreactive T cell activation. J Immunol. 2000;164:2405–2411. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adorini L, Penna G, Giarratana N, Roncari A, Amuchastegui S, Daniel KC, Uskokovic M. Dendritic cells as key targets for immunomodulation by Vitamin D receptor ligands. J.Steroid Biochem.Mol.Biol. 2004;89-90:437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hewison M, Burke F, Evans KN, Lammas DA, Sansom DM, Liu P, Modlin RL, Adams JS. Extra-renal 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1alpha-hydroxylase in human health and disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:316–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DiPaolo RJ, Brinster C, Davidson TS, Andersson J, Glass D, Shevach EM. Autoantigen-specific TGFbeta-induced Foxp3+ regulatory T cells prevent autoimmunity by inhibiting dendritic cells from activating autoreactive T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:4685–4693. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mathieu C, Waer M, Laureys J, Rutgeerts O, Bouillon R. Prevention of autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice by 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3. Diabetologia. 1994;37:552–558. doi: 10.1007/BF00403372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spach KM, Nashold FE, Dittel BN, Hayes CE. IL-10 signaling is essential for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-mediated inhibition of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:6030–6037. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daniel C, Sartory NA, Zahn N, Radeke HH, Stein JM. Immune modulatory treatment of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid colitis with calcitriol is associated with a change of a T helper (Th) 1/Th17 to a Th2 and regulatory T cell profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:23–33. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang J, Zhou R, Luger D, Zhu W, Silver PB, Grajewski RS, Su SB, Chan CC, Adorini L, Caspi RR. Calcitriol suppresses antiretinal autoimmunity through inhibitory effects on the Th17 effector response. J Immunol. 2009;182:4624–4632. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gorman S, Kuritzky LA, Judge MA, Dixon KM, McGlade JP, Mason RS, Finlay-Jones JJ, Hart PH. Topically applied 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 enhances the suppressive activity of CD4+CD25+ cells in the draining lymph nodes. J Immunol. 2007;179:6273–6283. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.6273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miyara M, Amoura Z, Parizot C, Badoual C, Dorgham K, Trad S, Kambouchner M, Valeyre D, Chapelon-Abric C, Debre P, Piette JC, Gorochov G. The immune paradox of sarcoidosis and regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:359–370. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miyara M, Yoshioka Y, Kitoh A, Shima T, Wing K, Niwa A, Parizot C, Taflin C, Heike T, Valeyre D, Mathian A, Nakahata T, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M, Amoura Z, Gorochov G, Sakaguchi S. Functional Delineation and Differentiation Dynamics of Human CD4(+) T Cells Expressing the FoxP3 Transcription Factor. Immunity. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, Lei KJ, Li L, Marinos N, McGrady G, Wahl SM. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25− naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1875–1886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Apostolou I, von Boehmer H. In vivo instruction of suppressor commitment in naive T cells. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1401–1408. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liang S, Alard P, Zhao Y, Parnell S, Clark SL, Kosiewicz MM. Conversion of CD4+ CD25− cells into CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in vivo requires B7 costimulation, but not the thymus. J Exp Med. 2005;201:127–137. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walker MR, Carson BD, Nepom GT, Ziegler SF, Buckner JH. De novo generation of antigen-specific CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells from human CD4+CD25− cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4103–4108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407691102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manzotti CN, Tipping H, Perry LCA, Mead KI, Blair PJ, Zheng Y, Sansom DM. Inhibition of human T cell proliferation by CTLA-4 utilizes CD80 and requires CD25+ regulatory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2888–2896. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2002010)32:10<2888::AID-IMMU2888>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takahashi T, Tagami T, Yamazaki S, Uede T, Shimizu J, Sakaguchi N, Mak TW, Sakaguchi S. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Exp Med. 2000;192:303–310. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Read S, Greenwald R, Izcue A, Robinson N, Mandelbrot D, Francisco L, Sharpe AH, Powrie F. Blockade of CTLA-4 on CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells abrogates their function in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;177:4376–4383. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmidt EM, Wang CJ, Ryan GA, Clough LE, Qureshi OS, Goodall M, Abbas AK, Sharpe AH, Sansom DM, Walker LS. Ctla-4 controls regulatory T cell peripheral homeostasis and is required for suppression of pancreatic islet autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2009;182:274–282. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wing K, Onishi Y, Prieto-Martin P, Yamaguchi T, Miyara M, Fehervari Z, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science. 2008;322:271–275. doi: 10.1126/science.1160062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zheng Y, Manzotti CN, Burke F, Dussably LM, Qureshi O, Walker LSK, Sansom DM. Acquisition of suppressive function by activated human CD4+ CD25− T cells is associated with the expression of CTLA-4 not FoxP3. J.Immunol. 2008;181:1683–1691. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cantorna MT, Mahon BD. Mounting evidence for vitamin D as an environmental factor affecting autoimmune disease prevalence. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2004;229:1136–1142. doi: 10.1177/153537020422901108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Munger KL, Levin LI, Hollis BW, Howard NS, Ascherio A. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of multiple sclerosis. Jama. 2006;296:2832–2838. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.23.2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]