Abstract

Bacterial toxin-mediated diarrheal disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In this work we designed an on-bead library of protease-resistant, acid-stable peptoid molecules and screened for high affinity binding of cholera toxin. From 100,000 compounds, we discovered a single sequence of residues that can bind and retain cholera toxin at high affinity when immobilized on a solid-phase particle. Furthermore, we demonstrate that these peptoid-displaying particles can sequester active cholera toxin from cell culture media sufficient to protect intestinal cells. We foresee this work as contributory to a potential adjunct therapeutic strategy against cholera infections and other toxin-mediated diseases.

Bacterial-mediated diarrheal disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and much of this can be attributed to the effects of secreted toxins on the gastrointestinal enterocyte.1 For example, the World Health Organization reported 150,000 cases of diarrheal disease secondary to the toxin-secreting bacteria Vibrio cholera in 2005. This figure is estimated to constitute only 5–10% of actual infections with the most recent outbreak occurring in Zimbabwe.2 In the United States, a toxin-mediated colitis attributable to Clostridium difficile typically occurs at an annual rate of three million cases per year.3 Finally, the leading cause of acute renal failure in children is hemolytic uremic syndrome initiated by a shiga-like toxin secreted by enterohemoragic E. coli (EHEC)4

The most common method for treating diarrheal disease is supportive treatment by replacing fluids and electrolytes in combination with antibiotics. However, there are limitations to the use of antibiotics with respect to the aforementioned classes of pathogens. First, it is well known that many bacteria become resistant to commonly-used antibiotics.5 Second, many antibiotics are ineffective against the acute effects of toxin-mediated diarrheal disease. Finally, administration of antibiotic therapy can exacerbate the disease by inducing large amounts of toxin secretion. This has been proven in the case of EHEC infections and current recommendations are to avoid antibiotic therapy when treating patients infected with the bacteria.4 For these reasons, ancillary strategies to defend against toxin-mediated bacterial disease are needed.

An alternative therapeutic strategy would be to create high-affinity binding particles that sequester bacterial toxins in the gut. The administration of binding particles to the gut is not a novel concept.6 For example, cholestyramine has been utilized for decades to non-specifically reduce cholesterol absorption.7 Likewise, tolevamer is an anion-exchange resin that has shown promise in reducing the morbidity associated with Clostridium difficle colitis.8 These resins bind their target molecules primarily through non-specific ionic interactions. Next-generation sequestrants would likely be more effective if the binding particle were selective, and had a higher affinity, for the targeted toxin. In this work, we demonstrate the discovery and utilization of an immobilized peptoid ligand for sequestering a specific bacterial toxin.

Cholera toxin (CT) was chosen as a convenient and clinically-relevant target for investigating this strategy. CT is a protein complex that includes a homopentameric ring of B subunits that bind to ganglioside GM1 on target cell membranes. This pentamer cradles a single A subunit, which is comprised of two peptides linked by a single disulfide bond. After binding to a target mucosal cell, the A subunit translocates across the cell membrane and the disulfide bond is reduced to produce the enzymatically-active A1 subunit, which cataylzes ADP-ribosylation of the regulatory GTPase Gas, preventing the inactivation of adenylate cyclase. The resulting accumulation of cyclic AMP stimulates mucosal cells to secrete chloride ion. The osmotic and electrical gradients created by the movement of ions causes water and various electrolytes to follow, leading to the diarrheal disease that is characteristic of infection.9

To identify CT-specific ligands, we utilized on-bead screening of peptoid libraries, which are rich sources of protein-binding ligands.10 The on-bead screening approach is particularly appropriate for this application since these molecules will be used as immobilized ligands, not soluble drugs. Furthermore, peptoids are ideal for applications in the gastrointestinal tract because they are both protease- and acid-resistant.11 Thus, split and pool synthesis was used to construct a one-bead one-compound (OBOC) peptoid library on hydrophilic Tentagel beads with a theoretical diversity of 105 (100,000) compounds. This was accomplished by incorporating the nine amines shown in Figure 1a via microwave-assisted sub-monomer peptoid synthesis,12 plus the inclusion of proline via peptide coupling. These side chains were chosen so that the library would encompass a variety of physiochemical properties. A linker sequence was included at the C-terminus to facilitate identification of hit compounds by tandem mass spectrometry. The methionine residue permits cyanogen bromide-mediated cleavage of compounds from individual beads and the tri-peptoid linker aids in MS analysis by providing both an ionizable group and a constant region that allows complete sequencing of the N-terminal diverse region of individual compounds.

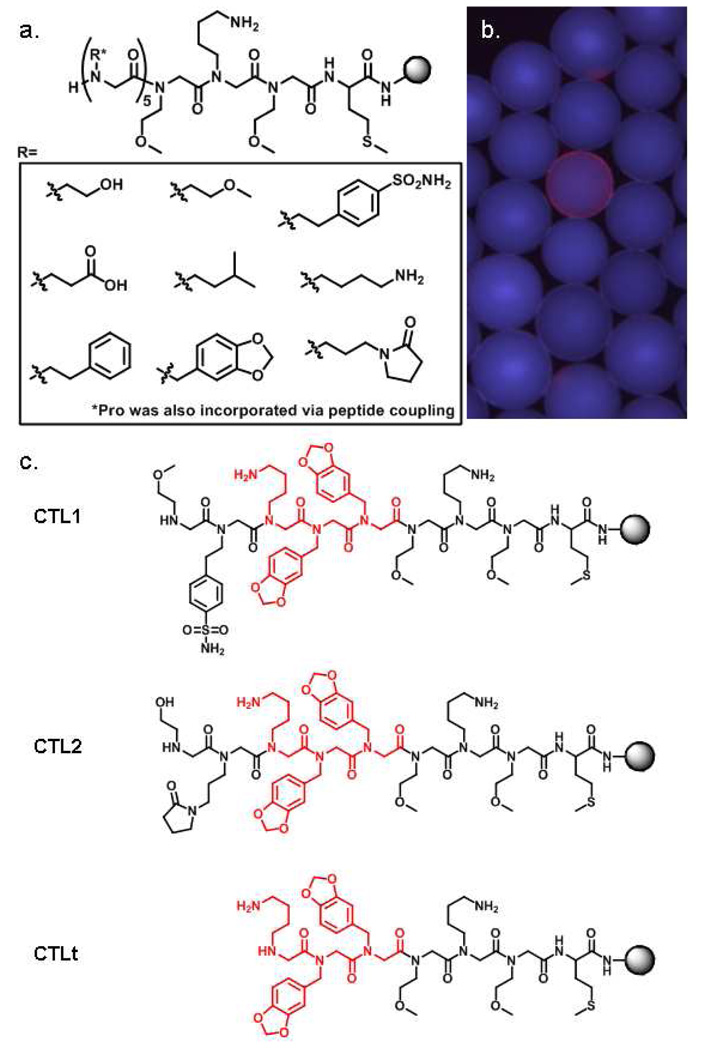

Figure 1.

(a) General structure of the peptoid library employed in the screen. A methionine residue and three peptoid residues at the C-terminus were fixed and the remaining five residues were diversified. Nine amines, incorporated as peptoid side chains, and the amino acid proline were used as monomers in the diverse portion. (b) A fluorescence micrograph of a single bead displaying a red halo. (c) CTL1 and CTL2 were sequences selected from the library as ligands for CT subunit B. The conserved portion is highlighted in red. CTLt (truncated) was used in all validation experiments.

For screening, approximately 100,000 library beads were blocked with 5% milk, then exposed to biotinylated cholera toxin subunit B (350 nM) in TBST buffer. After incubation, the beads were washed thoroughly and probed with streptavidin-conjugated red-emitting quantum dots. The beads were then visualized under a fluorescent microscope and those that displayed a red-halo (54 total, example in Figure 1b) were isolated manually using a micropipette. The isolated beads were stripped of protein with 1% SDS and then re-probed with streptavidin-conjugated quantum dots to identify compounds that bind directly to streptavidin rather than CT subunit B. We have observed the general tendency for streptavidin to bind a small portion of compounds from many of the peptoid libraries that we have created (unpublished observations). In this study, we identified streptavidin-binding peptoids in a post-screening step, although one could also easily pre-screen the library against streptavidin to remove these peptoids. Only two beads (0.002% of the library) did not bind the streptavidin-conjugated quantum dots directly and thus presumably displayed CT subunit B ligands. These beads were treated with cyanogen bromide to cleave at the methionine residue, and the sequence of each peptoid was then determined by tandem MALDI mass spectrometry (Supplementary information). Gratifyingly, a conserved sequence of three residues was shared by the two peptoids (CTL1 and CTL2, Figure 1c).

To validate that we had indeed identified specific CT subunit B ligands, a truncated peptoid (CTLt) that included the linker and the three conserved residues was re-synthesized on Tentagel beads and characterized further. First, we assayed cholera toxin subunit B binding in the presence of large amounts of competitor proteins. If the peptoid ligand is non-specific, then the excess competitor proteins should strongly inhibit binding of the toxin to the beads. Thus, the beads were blocked with 5% milk in TBST and then incubated with 10% fetal bovine serum or E. coli extract, each containing 200 nM biotinylated CT subunit B. In the case of the cellular extract, this represented a 120-fold excess of non-specific proteins over the CT subunit. Binding was visualized as before by utilizing streptavidin-conjugated quantum dots. The immobilized peptoids were able to bind the toxin under these demanding conditions. Binding from serum was comparable to binding out of TBST buffer alone (Figure 2a and 2b). However, less toxin was apparently isolated from the E. coli extract as indicated by the lower fluorescence intensity of these beads (Figure 2c). This result suggests that toxin binding sites were partially blocked by proteins in the extract. Signal was not observed in the absence of toxin, indicating that the CLTt-displaying beads do not bind the non-target multimeric protein streptavidin (Figure 2d).

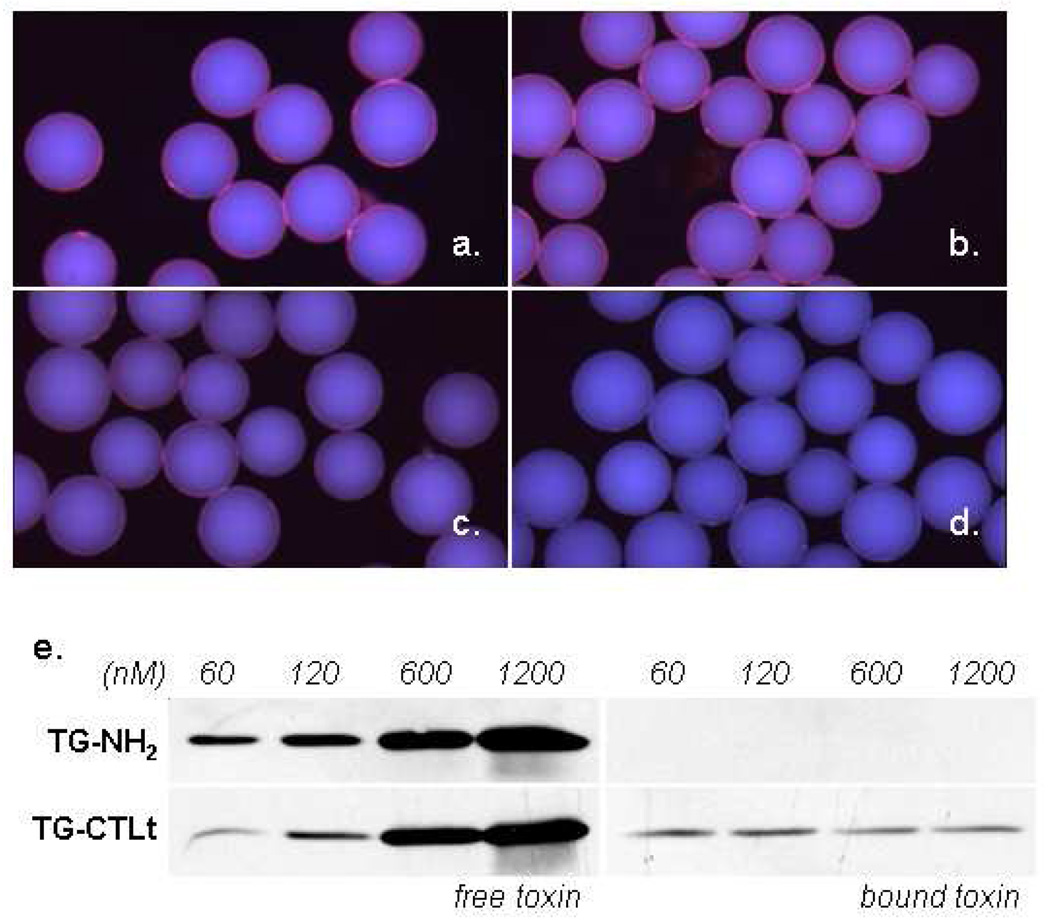

Figure 2.

Binding of cholera toxin to CTLt-displaying beads under diverse conditions. (a) Binding of CT subunit B at 200 nM to CTLt-displaying beads in TBST (Tris Buffered Saline with 1% Tween-20). (b) Binding of CT subunit B at 200 nM in RPMI cell culture media with 10% fetal bovine serum. (c) Binding of CT subunit B at 200 nM in 2 mg/ml E. coli extract. (d) CTLt-displaying beads incubated with streptavidin Q-dots alone. (e) Binding of the full CT complex. CT was incubated at the indicated concentrations in a mixture of 5% milk in TBST (350 µl total) and 2000 beads. After 30 minutes, the supernatant was removed and the beads were washed three times with TBST. Free toxin denotes the unbound toxin remaining in the supernatant. Bound toxin was the protein removed from the beads at the various concentrations after stripping with 350 µl of 1% SDS. TG-NH2 (unconjugated Tentagel-NH2), TG-CTLt (CTLt-displaying beads)

Next, the capacity of these particles to bind and retain the full cholera toxin complex was measured by incubating aliquots of CTLt-displaying beads (~2000) with various concentrations of CT in 5% milk. After removing the supernatant (free toxin) and washing, bound toxin was stripped from the beads with 1% SDS in a volume equal to the initial toxin solution. This permitted comparison of the relative amounts of free and bound toxin by gel electrophoresis and Western blotting of bound and free fractions (Figure 2e). As expected, beads that are not conjugated with a peptoid ligand (TG-NH2) do not bind the toxin in this assay. When displayed on beads, the CTLt ligand (TG-CTLt) was able to bind toxin present at nanomolar concentrations. Indeed, a clear reduction in the amount of free toxin at 60 and 120 nM can be seen after incubation with the TG-CTLt beads when compared to incubation with TG-NH2 beads.

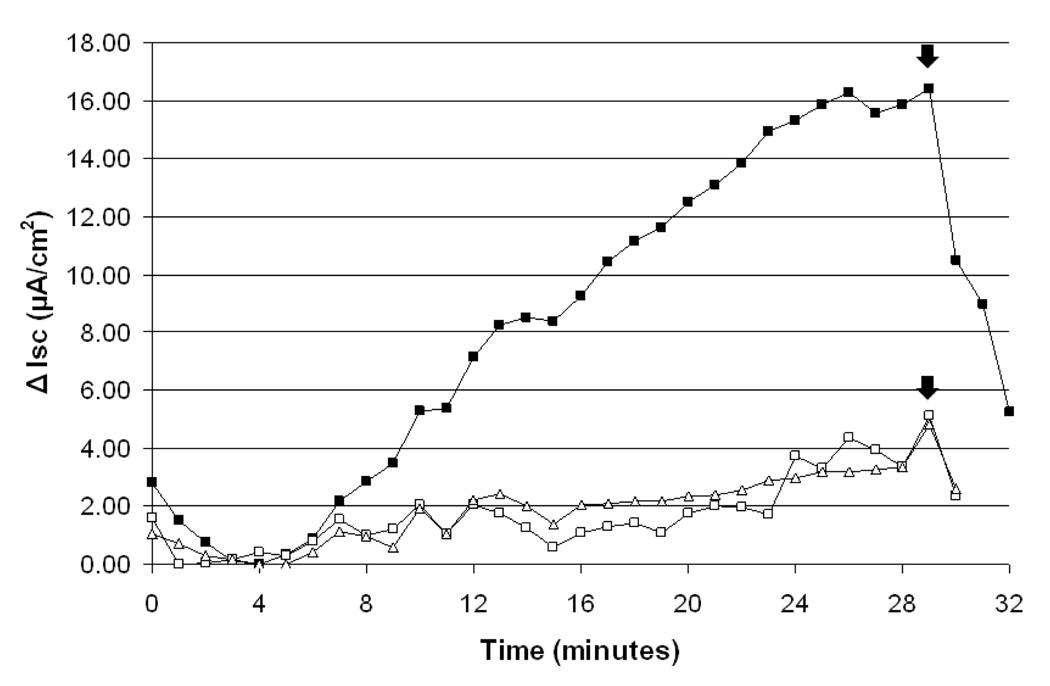

With a specific toxin-binding particle in hand, we determined if the particles could defend human intestinal cells from the effects of CT in cell culture at physiologically-relevant concentrations of active toxin. T84 human intestinal cells were chosen as a relevant model system for this work. The T84 cell line, when grown as a confluent monolayer on a permeable support, responds to cholera toxin with cAMP-dependent chloride secretion that produces a measurable current.9 Indeed, when a monolayer of T84 cells was incubated with cholera toxin (1 nM) in cell culture media, a pronounced secretory response was observed by measuring the short-circuit current across the cell monolayer (Figure 3). However, when the toxin-containing media was exposed to aliquots of CTLt-displaying beads (~5000) before incubating it with cells, the effect of the toxin was reduced dramatically, indicating that the toxin had been sequestered. This experiment supports the idea that the immobilized peptoid could protect intestinal epithelia from the toxin through sequestration if peptoid-displaying particles were ingested.

Figure 3.

Sequestration of cholera toxin from cell culture media. The current (Isc) represents the net sum of the transepithelial anion and cation fluxes and reflects the level of ion and fluid secretion.13 Cell monolayers were pre-incubated with CT-containing media for 40 minutes at 37 °C before removing the media and beginning measurement of Isc at t=0. To eliminate the contribution of Ca2+- or ATP-activated chloride secretion, P2- and IP3-receptor antagonists (suramin and 2-APB) were used during recording. (-■-) Positive control: cells pre-incubated with CT (1 nM) in 1.5 ml of culture media. (-□-) Trial 1: CT (1 nM) in 1.5 ml of culture media was exposed to ~5000 CTLt-displaying beads. After 30 minutes, the media was removed from the beads and placed over the cells for the 40-minute pre-incubation period. (-Δ-) Trial 2: repeat of Trial 1. Arrows denote the addition of glibenclamide, a chloride-channel blocker. All currents were normalized to a negative control (current measured with no toxin) and experiments were run sequentially on the same apparatus.

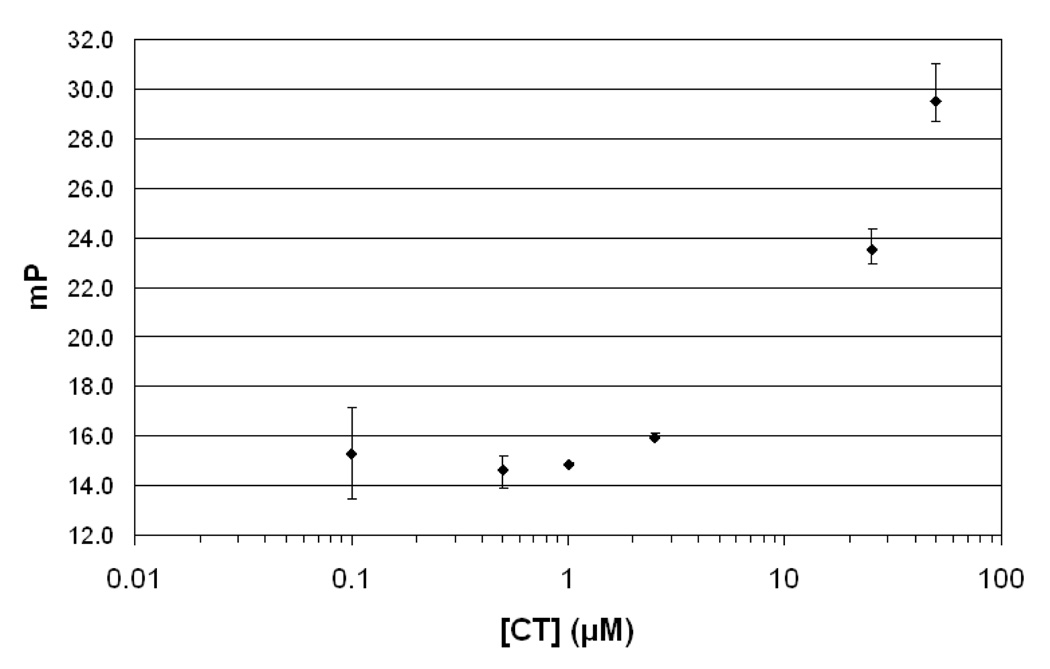

The high apparent affinity of the bead-displayed peptoids for the toxin is superficially surprising, given that our experience with peptoid library screening is that the primary hits usually bind to their protein targets with low µM KD’s. However, it is likely that the interaction between the pentameric toxin subunit B and the immobilized peptoid may be substantially enhanced by aviditiy effects.14 Fluorescence polarization experiments were employed to measure the intrinsic affinity of fluorescein-labeled, soluble CTLt for CT. As expected, the KD of this complex was in the µM range in the absence of any opportunity for multivalent binding (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Binding of fluorescein-labeled CTLt to cholera toxin as measured by fluorescence polarization experiments. The labeled peptoid (10 nM) was incubated with a concentration gradient (0.1 µM to 50 µM) of CT in TBST at room temperature for 30 minutes before measuring polarization (mP).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that a high-quality CT subunit B ligand can be identified from a modest-sized OBOC peptoid library. Because of an avidity effect, the immobilized peptoid acts as a high affinity toxin capture agent, able to efficiently sequester the bacterial toxin. These findings set the stage for animal experiments in which peptoid-displaying particles are introduced into the gut along with bacteria. The results of these efforts will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Experimental details, mass spectra, and complete reference 11. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. David Chen (UTSW) for providing access to the fluorescence microscope. This project was funded with federal funds as part of the NHLBI Proteomics Initiative of the National Heart, Lung & Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract No. NO1-HV-28185, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (FERANC08G0), and the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) of the National Institute of Health grant RO1 DK078587 (APF).

References

- 1.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Lancet. 2006;367:1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Cholera. 2009 January; http://www.who.int/topics/cholera/en/.

- 3.Schroeder MS. Am. Fam. Physician. 2005;71:921–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Taubes G. Science. 2008;321:360. doi: 10.1126/science.321.5887.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheiring J, Andreoli SP, Zimmerhackl LB. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2008;23:1749–1760. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-0935-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saha D, Karim MM, Khan WA, Ahmed S, Salam MA, Bennish ML. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:2452–2462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan R. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003;2:347–360. doi: 10.1038/nrd1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaffner F. Gastroenterology. 1964;46:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Louie TJ, Peppe J, Watt CK, Johnson D, Mohammed R, Dow G, Weiss K, Simon S, John JF, Jr, Garber G, Chasan-Taber S, Davidson DM. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006;43:411–420. doi: 10.1086/506349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lencer WI, Delp C, Neutra MR, Madara JL. J. Cell Biol. 1992;117:1197–1209. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.6.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alluri PG, Reddy MM, Bachhawat-Sikder K, Olivos HJ, Kodadek T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:13995–14004. doi: 10.1021/ja036417x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zuckermann RN, Martin EJ, Spellmeyer DC, Stauber GB, Shoemaker KR, Kerr JM, Figliozzi GM, Goff DA, Siani MA, Simon RJ, et al. J. Med. Chem. 1994;37:2678–2685. doi: 10.1021/jm00043a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Fowler SA, Stacy DM, Blackwell HE. Org. Lett. 2008;10:2329–2332. doi: 10.1021/ol800908h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon RJ, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:9367–9371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olivos HJ, Alluri PG, Reddy MM, Salony D, Kodadek T. Org. Lett. 2002;4:4057–4059. doi: 10.1021/ol0267578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlenker T, Romac JM, Sharara AI, Roman RM, Kim SJ, LaRusso N, Liddle RA, Fitz JG. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:G1108–G1117. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.5.G1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mammen M, Choi SK, Whitesides GM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:2755–2794. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981102)37:20<2754::AID-ANIE2754>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kitov PI, Sadowska JM, Mulvey G, Armstrong GD, Ling H, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Bundle DR. Nature. 2000;403:669–672. doi: 10.1038/35001095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Merritt EA, Zhang Z, Pickens JC, Ahn M, Hol WG, Fan E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:8818–8824. doi: 10.1021/ja0202560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental details, mass spectra, and complete reference 11. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.