Abstract

Chromobacterium violaceum is a gram negative straight rod, 0.8-1.2 by 2.5 to 6.0 µm, which is motile by one polar flagella and one to four lateral flagella. The organism inhabits soil and water and is often found in semitropical and tropical climates. Infections in humans are rare. We report a case of infection caused by strains of C. violaceum. A 38-year-old male patient was admitted to KyungHee University Hospital, Seoul, Korea on July 28th, 2003, after a car accident. The patient had multiple trauma and lacerations. He had an open wound in the left tibial area from which C. violaceum was isolated. The strain was resistant to ampicillin, tobramycin, ampicillin/sulbactam, ceftriaxone and cefepime, but was susceptible to amikacin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and piperacillin/tazobactam. The patient was treated successfully by debridement, cephapirin sodium and astromicine sulfate.

Keywords: Chromobacterium violaceum, wound infection

INTRODUCTION

C. violaceum inhabits soil and water and is often found in semitropical and tropical climates.1,2 C. violaceum is generally considered nonpathogenic and infections are rare. The pathogenic potential of this organism was first described by Wooley in 1905.3 The first human infection caused by C. violaceum was reported in Malaysia in 1927.4 In Korea, two cases of C. violaceum infections were reported in patients injured in a Guam airplane accident.5 We describe the first reported case of a local C. violaceum infection in Korea, as opposed to an imported case.

CASE REPORT

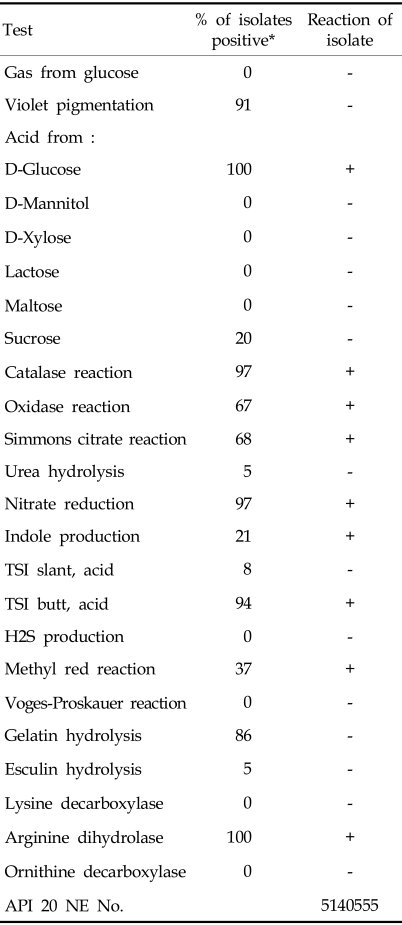

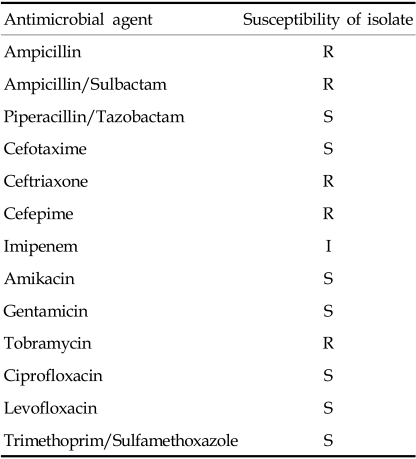

A 38-year-old-male patient had multiple trauma due to a car accident while fishing on the Soyang River in KangWon province, in Korea. He was first admitted to WonJu-Christian Hospital and then transferred to KyungHee University Hospital. He had hemothorax and empyema, a 4th rib fracture, an open wound in the left tibial bone, liver hematoma and kidney hematoma. From the open wound in the left tibial bone, the organism was cultured. The colony was colorless on blood agar and MacConkey agar plates. It was gram negative rods on Gram-stained smears. On blood agar it showed beta hemolysis. The isolate was identified as C. violaceum by conventional biochemical test and API 20 NE and Vitek system (Table 1). Antibiotic susceptibility tests were performed by the disk diffusion method. The stain was resistant to ampicillin, tobramycin, ampicillin/sulbactam, ceftriaxone and cefepime, but was susceptible to ciprofloxacin, amikacin, gentamicin, levofloxacin, trimethoprim/ulfamethoxazole and piperacillin/tazobactam (Table 2).

Table 1.

Biochemical Characteristics of Chromobacterium violaceum Isolate

*Data are from Weyant et al.14

Table 2.

Antibiotic Susceptibilities of Chromobacterium violaceum Isolate

R, resistant; I, intermediate; S, susceptible.

The patient was successfully treated with cephapirin sodium, astromicine sulfate and debridement. After 1 week, the organism was not isolated.

DISCUSSION

C. violaceum infections have been reported in Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia, the United States and so on.6-10 The pathogenic potential of this organism was first described by Wooley in 1905,3 the first human infection was reported in Malaysia in 19274 and few human cases have been reported since.6-10 The organism inhabits soil and water and is often found in semitropical and tropical climates. Although Korea is located in a temperate region, the hot summer weather might contribute to this infection. Hence, C. violaceum can exist in the Korean climate. The two prior Korean infection cases were both imported cases,5 so this is the first reported local case. C. violaceum is a potentially serious threat to patients with chronic granulomatous disease who visit or live in the endemic states in the months of June through September.3 In our case, the patient was a heavy drinker and his liver enzyme was elevated, so he had abnormal liver function which partially contributed to the infection. The portal of entry is a skin lesion leading to wound infection. Septicemia may develop, is significantly associated with neutrophil dysfunction, and has a high fatality rate.10 From the wound, only C. violaceum was isolated, suggesting that C. violaceum was the causative agent of the infection. The organism enters the body through a minor trauma to the skin or ingestion of contaminated water. In this case the patient suffered skin injury in a car accident. Sepsis is the most common feature of this infection, but this patient did not show sepsis.

In our case, a non-pigmented strain was isolated. There has been strong debate regarding the pathogenicity of the nonpigmented strains, but the reported infectivity rates of pigmented and non-pigmented strains are comparable. Pigmentation is not an essential characteristic in the definition of the genus Chromobacterium.11

In our case, C. violaceum was oxidase positive, indole positive, Voges-Proskauer reaction negative and esculin negative. The strain may be differentiated by fermentation of D-glucose, mannitol, maltose, and their lysine decarboxylase and ornithine decarboxylase activities from Vibrio or Aeromonas.5

C. violaceum is generally resistant to narrow-, extended-, and broad-spectrum β-lactam antibiotics, but is susceptible to ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole, tetracycline and imipenem.1 Rifampin and vancomycin are inactive, and erythromycin appears ineffective regardless of the susceptibility results.12 The virulence of nonpigmented cultures of C. violaceum and the pathology of their infections have been found to be similar to that of pigmented cultures for mice.13 It has been known for some time that nonpigmented variants arise upon subcultures of pigmented strains on artificial media. The patient was successfully treated with cephapirin sodium and astromicine sulfate.

References

- 1.Graveitz A, Zbinden R, Mutters R. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 8th ed. The American Society for Microbiology; 2003. Actinobacillus, Capnocytophaga, Eikenella, Kingella, Pasteurella, and other fastidious or rarely encountered gram-negative rods; pp. 616–617. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gauthier MJ. Morphological, physiological and biochemical characteristics of some violet-pigmented bacteria isolated from seawater. Can J Microbiol. 1976;22:138–149. doi: 10.1139/m76-019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macher AM, Casale TB, Fauci AS. Chronic granulomatous disease of childhood and Chromobacterium violaceum infections in the southeastern United States. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97:51–55. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-97-1-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sneath PHA, Whelan JPF, Singh RB, Edward D. Fetal infection by Chromobacterium. Lancet. 1955;(ii):276–277. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee J, Kim JS, Nahm CH, Choi JW, Kim J, Pai SH, et al. Two cases of Chromobacterium violaceum infection after injury in subtropical region. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2068–2070. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.2068-2070.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casalta, JP, Peloux Y, Raoult D, Brunet P, Gallais H. Pneumonia and meningitis caused by a new non-fermentative unknown gram-negative bacterium. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1446–1448. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.7.1446-1448.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dauphinais RM, Robben GG. Fetal infection due to Chromobacterium violaceum. Am J Clin Pathol. 1968;50:592–597. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/50.5.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ornibine AJ, Thomas E. Fetal infection due to Chromobacterium violaceum in Vietnam. Am J Clin Pathol. 1970;54:607–610. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/54.4.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman RB, Stern GA, Hood CI. Chromobacterium violaceum infection of the eye. A report of two cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:711–713. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030567019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts SA, Morris AJ, McIvor N, Ellis-Peger R. Chromobacterium violaceum infection of the deep neck tissues in a traveler to Thailand. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:334–335. doi: 10.1086/516913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sivendra R, Tan SH. Pathogenicity of nonpigmented cultures of Chromobacterium violaceum. J Clin Microbiol. 1977;5:514–516. doi: 10.1128/jcm.5.5.514-516.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGowan JE, Steinberg JP. Other gram negative bacilli. In: Mandel CL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Principles and practice of infectious disease. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; p. 2109. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sivendra R, Lo HS. Identification of Chromobacterium violaceum: pigmented and non-pigmented strains. J Gen Microbiol. 1975;90:21–31. doi: 10.1099/00221287-90-1-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weyant RS, Moss CW, Weaver RE, Hollis DG, Jordan JG, Cook EC, et al. Description of species. 2nd ed. Baltimore: The Williams and Wilkins Co.; 1996. Identification of unusual pathogenic gram-negative aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria; pp. 316–317. [Google Scholar]